In the United States, the field of ethnohistory grew out of the process of investigating and resolving American Indian land claims. Its origin is most appropriately traced to passage of the Indian Claims Commission Act in 1947, which “created a special court in which class actions by and on behalf of American Indians could be brought to correct inadequate compensation for lands taken in the past century” (Nash, 1988:270). Lawsuits heard by that court revolved around evidence about Indian communities and traditional life. The evidence necessary to support or oppose the associated land claims typically required the use of both documentary historical sources and ethnographic data, hence the term “ethnohistory,” introduced by William N. Fenton in 1952 (see also Sturtevant, 1966). As he noted at that time,

A certain strength in historical ethnology may be detected in the current flurry of demand by lawyers for the services of anthropologists who were trained in ethnohistorical research, and the challenge to adapt ethnological techniques to the materials of history for advancing or defending Indian claims against the Government may develop a trend with a predictable future. (Fenton, 1952:331)

Ethnohistory did not arise from a particular inspirational theory and also was not the brainchild of any single scholar; however, William Fenton was arguably the field’s preeminent leader and was instrumental in shaping its methodology.1 Fenton’s early ethnohistorical works were purely academic (e.g., Fenton, 1940, 1941), but when the field of ethnohistory actually came into being, its initial orientation was instead more practical, as it concerned the application of knowledge to useful ends: the evaluation of Indian land claims (see also Fenton, 1952:337–338).

The many variant definitions of the term ethnohistory in the anthropological literature reflect the field’s evolution over time (see also Krech, 1990; Harkin, 2010). Fenton (1966:75) defined ethnohistory as “the critical use of ethnographic concepts and materials in the examination and use of historical source material.” In its most fundamental form, the term refers to a research methodology that combines ethnographic or archaeological data with archival and written historical materials to produce ethnographic reconstructions or document culture change (see also Lantis, 1970c:4–5; VanStone, 1970b, 1983b:289–291). But it is also a time-oriented approach (Oswalt, 1990:xiii–xviii; see also Krech, 2006) that, in ideal circumstances, incorporates oral history and linguistic data as well. Thus, the ethnohistorical method is founded on the principle that the most reliable reconstructions of cultural history are those that employ multiple lines of evidence, all of which are subjected to critical evaluation (see also Fenton, 1962; Trigger, 1987:11–26; Barber and Berdan, 1998:247–273). The importance of critically evaluating the data on which a study rests cannot be overstated: that task is absolutely essential to sound ethnohistorical research.

Figure 12.1 Orientation map with selected indigenous locations/sites critical to Alaska ethnohistorical studies, 1940–1985.

The primary objective of this essay is to review the contributions of scholars who played leading roles in the development of ethnohistory as a methodology for the study of Alaska Eskimo societies (Figure 12.1). The focus here is on the period from about 1940 to 1985, but later contributions are also mentioned to provide a fuller sense of historical context. Rather than a comprehensive treatment of the subject, this essay is instead one practitioner’s perspective on the origins and present state of Alaska Eskimo ethnohistory.

As implied above, ethnohistorical studies of American Indian populations in the continental United States predated any such studies involving Alaska Eskimo populations; they also provided templates for nascent Eskimo ethnohistorians to follow. A number of outstanding early ethnohistorical-type studies of non-Eskimo societies in Alaska were also available to stimulate Eskimo scholars with similar methodological inclinations. They included works by Cornelius Osgood (1905–1985) on the Tanaina (Dena’ina; 1937) and Ingalik (Deg Hit’an; 1940, 1958); by Kaj Birket-Smith (1893–1977) and Frederica de Laguna (1906–2004; Fitzhugh, this volume) on the Eyak (1938); and by de Laguna on Athabascan groups in the Tanana and Yukon River valleys (1947). Studies such as these were remarkable for their scope and because the authors sought out and profitably utilized diverse types of data to address their subjects. The influences they ultimately had on the growth of Alaska Eskimo ethnohistory underscore not only the innovation and impressive scholarship of their authors but also the small circle of northern anthropologists at the time.

Eskimo ethnohistory was arguably introduced to Alaska by Danish anthropologist Kaj Birket-Smith through his work on the Chugach (1953; see also Birket-Smith, 1941) in the 1930s. He cannot accurately be called an ethnohistorian, but his academic training made him appreciate the value of historical records. Margaret Lantis (1906–2006; Figure 12.2) was the first anthropologist to conduct Alaska Eskimo studies that may justifiably be characterized as ethnohistorical in their approach. The most notable examples are her monograph on the social culture of the Nunivak Eskimo (Lantis, 1946; Figure 12.3) and her seminal paper on Western Yup’ik folk medicine and hygiene (Lantis, 1959). Both were ethnographic in nature but incorporated other supplementary data sources. She was also a leader in realizing the value of archival records for ethnohistorical investigations concerning Alaska Eskimos. This is evidenced by her earlier papers on Koniag mythology (Lantis, 1938a) and the Alaskan whale cult (Lantis, 1938b, 1940) and a monograph on Alaskan Eskimo ceremonialism (Lantis, 1947), which was the published version of her Ph.D. dissertation (Lantis, 1939).

Figure 12.2 Margaret Lantis, ca. 1953. Photograph by John Van Willigen. University of Kentucky Archives, Portrait Print Collection, Department of Anthropology, Accession No. 2625.

Figure 12.3 Walter Amos (Tutqir), foreground, and other Nunivak Islanders preparing for a winter trip, January 1956, Mekoryuk, Alaska. Photo by Margaret Lantis. Margaret Lantis Papers, Accession No. 2001-017, Box 2, Folder 3, Slide 18, Alaska and Polar Regions Collections, Elmer E. Rasmuson Library, University of Alaska Fairbanks.

Much of Lantis’s work was also openly reliant on Native oral history, which amounted to formal recognition that anthropologists should pay attention to local indigenous knowledge (e.g., Lantis, 1970a:135–137; see also Fienup-Riordan, 1999). De Laguna (Figure 12.4), another pioneer of Alaskan ethnohistory studies, was similarly open about the use of oral history in her monograph on the prehistory of the Chugach Eskimo (de Laguna, 1956), an archaeological study that constituted another early example of Alaska Eskimo ethnohistory.

Finally, Lantis (1970a) also conceived of and edited the first collection of papers on Alaskan ethnohistory, a volume that clearly expressed the approach’s hybrid nature and its broad applicability. It included papers by archaeologists and sociocultural anthropologists that ranged geographically and culturally from the Lake Iliamna Dena’ina (Townsend, 1970) to the Aleutian Islands (Lantis, 1970b) to Yup’ik Eskimos of the Cape Newenham (Ackerman, 1970) and Nushagak River (VanStone, 1970) areas and eastward to Athabascan and Tlingit peoples in the Alaska-Canada border region (McClellan, 1970).

Figure 12.4 Frederica de Laguna with Wallace de Laguna (left) and Norman Reynolds (right) at a midden, West Point, Palugvik, Hawkins Island, Alaska, 1933. Alaska State Library, Frederica De Laguna Photograph Collection, P350-33-129.

Although sociocultural anthropologists have been the main practitioners of ethnohistory, the methodology is by no means exclusive to any group of researchers. In fact, the unquestioned leaders of the second generation of Alaska Eskimo ethnohistorians—Wendell Oswalt (b. 1927; Figure 12.5) and James VanStone (1925–2001; Figure 12.6)—were both archaeologists by training. Their respective Alaskan careers began in direct association with J. Louis Giddings (1909–1964), a more senior archaeologist whose broad research interests also generated what can be considered ethnohistorical contributions (e.g., Giddings, 1952, 1956, 1961). Oswalt served as a young field assistant for Giddings in the Kotzebue-Kobuk region (1947) and at Cape Denbigh (1948) on Norton Sound. His Ph.D. dissertation, a study of the Yup’ik Eskimo village of Napaskiak on the lower Kuskokwim River (Oswalt, 1959), was the first completed on a topic in Alaska Eskimo ethnohistory. VanStone also worked with Giddings at Cape Denbigh (1950), then conducted an excavation at Kotzebue in 1951 that was the basis for his Ph.D. dissertation (VanStone, 1954).

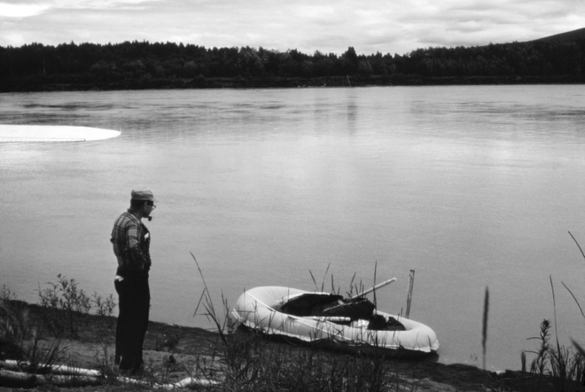

Figure 12.5 Wendell H. Oswalt on the middle Kuskokwim River during a boat trip from McGrath to Bethel, ca. 1971. Alaska State Library, Wendell H. Oswalt Photograph Collection, P550-75.

Like Lantis and de Laguna before them, Oswalt and VanStone also utilized Native oral history in their ethnohistorical studies, although both strongly emphasized written historical accounts. In fact, they shared a lack of confidence that Native oral accounts could be safely extended backward in time for more than about 50 years (e.g., Oswalt and VanStone, 1967:iv–v; cf. VanStone, 1968:341–344, 1970b:64). Their views on this matter were somewhat shortsighted. Their joint 1954 project at Crow Village, on the Kuskokwim River, and VanStone’s 1965 work at Tikchik Village, north of Bristol Bay, illustrate this point. Both sites had been occupied as recently as circa 1900, so the potential was high for Native informants to contribute to fuller understandings of their respective histories. That is, Natives who formerly lived at those sites (or had learned about them from their parents or grandparents) were still alive when the research programs of Oswalt and VanStone were in progress. In fairness, however, since the research at both sites was devoted mainly to excavations, Oswalt and VanStone may have had little time to spend in search of oral history.

Figure 12.6 James W. VanStone making an oil drum stove for his rented house in the Iñupiaq Eskimo village of Point Hope, Alaska, with the assistance and oversight of Bernard Nash (left), 1955. Photo by Mary Cox. Mary Cox Photographs, 1953–1958, Accession No. 2001-129-55, Alaska and Polar Regions Collections, University of Alaska Fairbanks.

Without question, Oswalt and VanStone were the individuals most responsible for firmly establishing ethnohistory as a research tool in the study of Alaska Eskimos. Both men had primary research interests in southwest Alaska—a region that lacked any preexisting archaeological record at the time of their entry. What the region did have, however, was a large Native population with numerous active villages, a fairly rich body of Russian American era (1741–1867) source materials (especially Zagoskin, 1967), and a number of important later American accounts (e.g., Dall, 1870; Nelson, 1899). Thus, it was a fertile ground for ethnohistorical studies. These factors strongly influenced their early field experiences in the region and played a large role in their movement away from old-school archaeological methods.

By their own account, Oswalt and VanStone adopted ethnohistorical methodologies because they recognized the serious interpretive limitations faced by archaeologists (see also Dumond, 1998). This decision is explained in the following passage from their book The Ethnoarchaeology of Crow Village, Alaska.

In the study of primitive people it seems sound to begin by first excavating historic sites. The comparative information available for the recent past is virtually always more complete than for the more distant past. Thus, it is logical to develop an archeological program in any particular geographical area by digging the recent sites and then working back in time to older sites. However, the overwhelming majority of archeologists compound their already staggering interpretive problems by being obsessed with antiquity. Thus many potentially useful sequences hang in uncertain limbo or are linked to history by frail suppositions and inferences. We hoped to avoid this pitfall through the kind of archeology we undertook. (Oswalt and VanStone, 1967:v)

The contributions of Oswalt and VanStone to Alaska Eskimo ethnohistory are numerous, major, and diverse. Their shared interests are indicated by their respective publications on many similar subjects, including Eskimo community studies (e.g., VanStone and Oswalt, 1960; VanStone, 1962b; Oswalt, 1963a; see also Chance, 1960; Hughes, 1960; Burch, 1981a; Griffin, 2004), culture contact and change (Oswalt, 1960, 1963b, 1979, 1990; VanStone, 1967, 1978, 1983a; Michael and VanStone, 1983; Dumond and VanStone, 1995; see also Mason, 1975; Wolfe, 1979), historic settlement patterns (VanStone, 1971; Oswalt, 1980a), material culture (e.g., Oswalt, 1972; VanStone, 1976, 1980), and Russian America (e.g., VanStone, 1959, 1972, 1977; Sarafian and VanStone, 1972; Oswalt, 1980b).

It is in the latter two subject areas that VanStone truly stands alone. Material culture studies he published (e.g., VanStone, 1980, 1989, 1990; VanStone and Simeone, 1986) went far beyond descriptive works: they were consistently rich in ethnohistorical data because he diligently performed the related research necessary to provide readers with extensive historical and contextual information about both the items being described and the people who made them (see also Fitzhugh and Kaplan, 1982). This commitment included several episodes of “field research in Alaska oriented specifically toward obtaining data on museum specimens” (VanStone, 1983b:299). His many contributions to the study of material culture were by no means limited to Alaska (e.g., VanStone, 1962a). No one before VanStone devoted so much effort to researching and writing up museum collections, and sadly, no one since appears to be following his example.

VanStone was also an American pioneer in recognizing the importance of Russian historical sources to Alaska Eskimo studies. His work in editing and annotating translations of Russian sources made an outstanding contribution to Alaskan ethnohistorical scholarship (e.g., VanStone, 1977, 1988). His introduction to Vassili Khromchenko’s journals from the coastal survey of southwest Alaska in 1822 (VanStone, 1973; see also VanStone, 1970a; Lantis, 1998) was an especially good example of VanStone’s intense interest in history and dedication to helping others learn from his own hard work. His commitment to Alaska Eskimo studies was also evidenced by the considerable time and energy he devoted to assisting Charles Lucier (1926–2013) with compiling and publishing key parts of Lucier’s extensive ethnographic and ethnohistorical research data (Lucier et al., 1971; Lucier and VanStone, 1987, 1991a, 1991b, 1992, 1995) and also by his write-up of Lantis’s field notes concerning Nunivak Eskimo material culture (VanStone, 1989).

Another important contributor to Alaska Eskimo ethnohistory of that second cohort was Dorothy Jean Ray (1919–2007; Figure 12.7), and the topical diversity of her work was also impressive. Perhaps best known for her monograph The Eskimos of Bering Strait (1975b), Ray published significant works on Eskimo place-names (1971), tenure and territoriality (1967b), settlement and subsistence patterns (1964, 1967c; see also Sheppard, 1983, 1986), trade (1975a), and oral traditions (1968). Her ethnohistorical knowledge also informed several influential works on Eskimo art (Ray, 1967a, 1977, 1980; see also de Laguna, 1932, 1933; Sonne, 1988; Fienup-Riordan, 1996; Haakanson and Steffian, 2009).

Figure 12.7 Dorothy Jean Ray with Chris Hugo (left) and Peter Morry (right) at Lucky Six Creek, Noatak River headwaters, Alaska, August 1947. Photo by Stanley Thompson. Dorothy Jean Ray Papers, Series 1 Biographical, Box 19, Folder 4, Accession No. 2008-040-719, Alaska and Polar Regions Collections, University of Alaska Fairbanks.

Although Ray may have utilized Native oral history in her work more than either Oswalt or VanStone, the quote that follows indicates she also had some serious misgivings about it as a data source:

Before the Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act of 1971, the Eskimo had relatively little feeling for history as a systematic area of knowledge and had only a rudimentary concept of chronology, dating, and the anecdotal aspects of historical events. Among the Eskimo there were specialists—musicians, sled makers, mask makers, story tellers—but no historians. To most Eskimos, specific dates meant nothing: genealogical depth extended only two or three generations; and knowledge was meager even on events occurring relatively recently. From most informants, the answers I received concerning such matters as establishment of the first schools in the Bering Strait area or the landing of the first reindeer at the first reindeer station, or details of government transactions such as those involved in the reindeer industry, were often quite inaccurate. (Because of this, the habit of journalists and popular writers to accept stories of the past from Eskimo spokesmen with the assumption that dating and sequence of events are correct has led to an abundance of erroneous writing.) (Ray, 1975b:vii)

Her stated opinion that Eskimos lacked historians was evocative of an assumption many anthropologists once held that “simpler peoples were without benefit of history” (Fenton, 1952:329). In what is believed to be her first professional paper, she even expressed skepticism about the accuracy of “stories and claims that Eskimos were good geographers” (Thompson, 1951:342). Nevertheless, Ray placed considerable stock in the statements of her Eskimo informants when considering certain historical problems. Her interpretation of ethnic boundaries in the Unalakleet River drainage (Ray, 1975b:171; cf. Pratt, 2012:104) is one example.

The point should be made here that the Department of Anthropology at the University of Alaska Fairbanks (UAF) was the center of Alaska Eskimo ethnohistory during its formative years. In the period extending from the late 1940s through the late 1950s, faculty, staff, and students in the department included Giddings, Lantis, Lucier, Oswalt, VanStone, and Ray—the last four of whom were then in the beginning of their professional careers. This must have been a stimulating and motivating environment for these scholars, and it was clearly beneficial to the field of ethnohistory. The collective efforts of the group’s younger members solidified ethnohistory’s value in the study of Alaska Eskimos and greatly expanded the range of topics to which the methodology was eventually applied. Also, in 1952 Oswalt and VanStone founded and jointly edited a new journal, Anthropological Papers of the University of Alaska. The UAF Department of Anthropology was responsible for its management and production, and the journal became an important early outlet for the publication of ethnohistorical research—most of which was exclusively academic and not directed toward practical ends or indigenous audiences.

An underappreciated watershed era in the field of Alaskan ethnohistory began with the 1971 passage by the U.S. Congress of the Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act (ANCSA), which awarded Alaska’s indigenous people a cash settlement and fee simple title to 40 million acres of land. Just as Indian land claims gave rise to the field of ethnohistory in the continental United States, one small piece of the ANCSA legislation, Section 14(h)(1), ultimately led to what is now the largest single collection of ethnohistorical data concerning Alaska Natives.2

Section 14(h)(1) of the Act allowed newly-created Native regional corporations to receive a portion of their acreage entitlements in the form of historical places and cemetery sites. This is the only part of the settlement that affords Alaska Natives the right to claim lands based specifically on their significance in cultural history and traditions. (Pratt, 2009b:4)

The term “cemetery sites” is self-explanatory, but “historical places” comprise a large variety of properties, including former villages, seasonal camps, landmarks, rock art sites, trails, and sites having legendary significance. Native regional corporations (Figure 12.8) interested in pursuing title to such properties had to file applications with the U.S. Department of the Interior, Bureau of Land Management (BLM). Every selected site required a stand-alone application that included a map plot of the site’s location and a narrative statement describing its significance in Native history. All timely filed applications were then subjected to land status reviews by the BLM.3 Applications describing sites the BLM determined to be on available (i.e., “vacant, unreserved and unappropriated”) federal lands at the time of application were forwarded to the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA), the agency implementing the regulations (i.e., 43 Code of Federal Regulations [CFR] 2653) and assigned primary responsibility for field investigating, reporting on, and certifying ANCSA 14(h)(1) claims. The regulations assigned the National Park Service (NPS) an important consulting role in the program’s implementation.

Figure 12.8 Names and geographic boundaries of ANCSA Native Regional Corporations. ANCSA 14(h)(1) Collection, Bureau of Indian Affairs, ANCSA Office, Anchorage, Alaska.

The NPS responsibilities were largely restricted to conducting archaeological, historical, and ethnographic research on ANCSA 14(h)(1) sites and providing the BIA with reports about those sites, including thoughts about their historical significance. All other aspects of the program’s implementation were the purview of the BIA. They included field planning and the setup of field camps; scheduling of site investigations; contracting for helicopters, vessels, and fixed-wing aircraft necessary to transport crews to the investigated sites; and providing crews to perform realty/land recording functions such as metes and bounds/boundary surveys for each site. Underscoring the agency’s controlling role in the program, the regulations also assigned the BIA responsibility for issuing certifications on each investigated site’s eligibility or ineligibility for title conveyance (based on the ANCSA eligibility criteria; see Pratt, 2009b:32n8).

Thus, the BLM land status review was only the first of several hurdles applications had to clear in order for the subject sites to become potentially eligible for conveyance to Native regional corporations. Subsequent stages of the ANCSA 14(h)(1) implementation process have been fraught with difficulties, the characters of which run the gamut from practical to technical to political. For these and other reasons, the ANCSA 14(h)(1) program methodology had to evolve through time, largely through trial and error (e.g., Drozda, 1995; Pratt, 2004, 2009b), but it has always been decidedly ethnohistorical in approach. In fact, successful implementation of Section 14(h)(1) was dependent on ethnohistorical research of a strongly practical nature, much of which was conducted in partnership with Alaska Native communities. When the program was launched in the mid-1970s, however, trained practitioners of ethnohistory were few.

Staff of the BIA consisted almost exclusively of individuals with training and work experience in federal land transactions (i.e., realty specialists), reflecting the agency’s interpretation that it was fundamentally a land transfer program. Established for the sole purpose of implementing the 14(h)(1) program, the BIA ANCSA office was placed under the direction of Larry P. Cooper Jr., a longtime realty specialist. In contrast, the NPS staff assigned to this program were mainly anthropologists and historians, members of a preexisting research arm of the agency designated the Anthropology and Historic Preservation, Cooperative Park Studies Unit (AHP-CPSU), directed by archaeologist Zorro Bradley (1925–2010) and based at UAF. This underscored the NPS’s opinion that the program was most directly concerned with cultural resources. These diverging perspectives were the source of disagreements between the respective agency staffs on a broad range of critical program matters, the most significant of which involved field methodology (especially relative to oral history research); data ownership, access, and use rights; and site eligibility determinations. The latter were the purview of BIA staff whose qualifications for evaluating the significance of historical and archaeological sites was suspect (see also Pratt, 2004, 2009b:18–19).

One early program issue on which the agencies did agree, however, was that Native regional corporations could use assistance in preparing their ANCSA 14(h)(1) site applications. Accordingly, both agencies made staff available to help interested regional corporations gather information about Native historical places and cemetery sites in their respective regions that could be used to generate individual site applications. Most regional corporations accepted this assistance, but several did not. For instance, Sealaska Corporation (based in southeast Alaska) instead accomplished that task by contracting with a professional consulting firm from the state of Washington. Hiring local Native people as guides and crew members, the firm’s staff traveled throughout southeast Alaska and successfully located and minimally recorded hundreds of Native historical sites, including documentation in oral history interviews, in a remarkably short period of time (see Sealaska Corporation, 1975). Similarly, the Northwest Alaska Native Association (NANA, Inc.) opted to hire anthropologist Ernest S. Burch Jr. and Rachel Craig (1930–2003), an Iñupiaq Eskimo resident of Kotzebue, to compile the data on which its 14(h)(1) site applications would be based. This effort combined the knowledge of an anthropologist very familiar with the region and its historical literature with oral history testimony gathered by a resident Native in local villages across the region. Finally, Cook Inlet Region, Inc. (CIRI) assembled a crew of student historians to collect oral history and site location information to generate its applications (Cook Inlet Historic Sites Project, 1975; see also Rabich, 1977).

The remaining eight regional corporations that filed ANCSA 14(h)(1) applications accepted assistance from BIA and/or NPS staff.4 A fairly typical example of the application production process among those regional corporations occurred in the Bering Straits Native Corporation (BSNC) region of western Alaska. There, NPS anthropologist Kathryn Koutsky (1) collected oral history information from Native residents about former villages, camps, cemeteries and other sites in region, (2) reviewed historical and archaeological sources for similar information, and (3) combined the two data sets to produce a comparatively comprehensive regional site inventory. Every BSNC 14(h)(1) application was generated by this inventory. Unlike in the Sealaska, NANA and CIRI regions, the application process followed by BSNC led to formal publications by AHP-CPSU in eight regional issues (i.e., Koutsky, 1981–1982; see also Sheppard, 1983) that made the assembled data readily available to other researchers. Although these BSNC-focused publications are unquestionably valuable sources of ethnohistorical data about the region, they must be used with a measure of caution. That is, every site described therein that became the subject of an ANCSA 14(h)(1) investigation has been much more fully documented since the publications were issued; some of that documentation revealed errors or inconsistencies in Koutsky’s prior work (e.g., Ganley, 2009). Similar AHP-CPSU publications resulted from assistance its staff provided in several other corporate regions (i.e., Andrews, 1977; Stein, 1977; Reckord, 1983), and the same cautionary note also applies to them.5 In spite of such shortcomings, the work leading up to preparation of the Native regional corporation site applications resulted in the compilation of voluminous ethnohistorical data (ethnographic, historical, archaeological, and linguistic). Even more such data were gathered during the subsequent site investigations.

The main objectives of every ANCSA 14(h)(1) investigation were to verify the physical existence and location of the subject site, establish its cultural significance and history of local Native use, and gather sufficient evidence to render an accurate and legally defensible certification of site eligibility based on the ANCSA regulations. Toward this end (as described in Pratt, 2009b), site investigations included reconnaissance-level archaeological surveys, the production of detailed site maps showing identified surface cultural features and their distributions across the sites, narrative feature descriptions, site and feature photographs, and reviews of archival and published sources relevant to the sites and immediate project areas. Site excavations did not occur, and subsurface testing was uncommon; it was usually performed only to verify the presence of buried cultural remains or to obtain organic samples for radiocarbon dating. Oral history research was undertaken with local Native Elders when possible, sometimes at the specific sites being investigated. The purpose of these interviews was to gather site-specific information (e.g., site names, types and seasons of use, approximate dates of abandonment), but collectively they contained information on nearly every topic imaginable concerning Alaska Native history (see Pratt, 2004).

Investigative findings were compiled in final site reports that were usually about 30 to 40 pages but sometimes exceeded 100 pages. In addition to an eligibility certification and information derived from the original application, each final site report typically included the following: a discussion of the site’s environmental setting, a review of oral and written accounts about its past use, narrative and/or tabular descriptions of the identified surface cultural remains (and buried cultural remains if documented), detailed site maps, and photographs of the site area and selected features (Pratt, 2009b:24).

The ANCSA 14(h)(1) Program was and still remains the largest and longest-running ethnohistorical-type program in Alaska history. It has employed several hundred researchers, many of whom essentially learned their trade on the program. More importantly, the program has generated a nationally unique, irreplaceable, and enormously rich collection of records concerning Alaska Native history and cultural traditions (e.g., Sattler, 2009). Its primary components include over 2,000 tape-recorded oral history interviews with Alaska Native Elders (many of whom spoke only Native languages), less than half of which have associated transcripts; notes on more than 600 additional untaped oral history interviews; roughly 2,300 (unpublished) site reports and 8,000 field notebooks; an estimated 40,000 to 50,000 photographic images; about 15,000 artifacts; a collection of some 130 composite field maps heavily annotated with Native place-names (e.g., O’Leary, 2009; Pratt, 2009e); plus extensive official correspondence files and an array of related materials (see O’Leary et al., 2009).6

The program’s remarkably long life, its linkages to scores of practicing anthropologists, and the unparalleled value of its associated records collection might suggest otherwise, but the fact is that there has historically been a major disconnect between ANCSA ethnohistory data and academic anthropologists, other researchers, and Alaska Natives. With few exceptions, about the only researchers who have made efforts to access and incorporate these data in professional publications or other public formats was a small cadre of past and present program employees.7 That said, ANCSA 14(h)(1) records can appropriately be characterized as an archival collection: they are unpublished and still require considerable processing, and the vast majority cannot be accessed remotely. Thus, access to and use of the collection can require considerable investments of time and concentrated determination.

The discussion now logically turns to Ernest S. Burch Jr. (1938–2010; Figure 12.9), most of whose ethnohistorical contributions postdate 1980 but rest squarely on his research in Alaska since 1964, particularly in 1969–1979, and also on the foundation laid by Lantis, Oswalt, VanStone and Ray. Burch was much more topically focused in his ethnohistorical work, devoting the bulk of his long career to the reconstruction of traditional Eskimo societies in northwest Alaska, their respective territorial boundaries, and their histories of interactions with one another (e.g., Burch and Correll, 1972; Burch, 1974, 1975, 1976a, 1979, 1980, 1981b, 1988b, 1998a, 1998b, 2005, 2006; Burch et al., 1999; see also Sheppard, 2009; Mason, 2012). His work in this realm deviated markedly from that of previous researchers in one key way: Burch’s primary source of data was not written accounts but Native oral history. This focus probably led to some interesting scholarly discussions between Burch and VanStone, given that the latter once asserted that

Figure 12.9 Ernest S. “Tiger” Burch Jr. and Matt Ganley (right) discussing a large stone-walled structure at Agiupaum Kania, a former Inupiat Eskimo caribou drive site on Seward Peninsula, Alaska, September 2009. Photo by Kenneth L. Pratt.

the substance of an ethnohistorical study must come from accounts written by those who observed and interacted with the [Natives] at a time when there were no anthropologists on the scene to record the changing lifeways of an indigenous culture. (VanStone, 1979:4)

It is also worth noting that Burch’s perspective on the temporal accuracy of Native oral history contrasted sharply with those of Oswalt and VanStone. Whereas they suggested a temporal limit of about 50 years, Burch believed the oral accounts of his informants in northwest Alaska accurately described conditions that existed up to 120 years earlier (e.g., Burch, 1998a:13; see also VanStone, 1983b:293–294; Pratt, 2009c:289–294). He also clearly disagreed with Ray’s assertion that there were no historians in traditional Eskimo society (e.g., Burch, 1998a:12–13; see also Campbell, 1998, 2004; Spearman, 2004).

Burch had not taken these positions lightly. They were instead the culmination of a trial and error process from which he ultimately learned that, if used critically, Native oral history can be a valid scientific research tool (see Burch, 2010). Burch’s (1991) paper “From Skeptic to Believer” candidly acknowledged his initial disregard for oral history and described resulting mistakes made in some of his prior research.8 This highly influential paper was an open plea to colleagues not to repeat such mistakes in their own work, and it helped establish the credibility of oral history in the study of Alaska’s Native people.

Although this paper may be Burch’s most valuable contribution to the methodology of Alaska Eskimo ethnohistory, three others merit comment. “The ‘Nunamiut’ Concept and the Standardization of Error” (Burch, 1976b; cf. Spencer, 1959) presents a detailed explanation of the genesis and perpetuation of an important early error in the naming and classification of Eskimo societies. “The Method of Ethnographic Reconstruction,” published posthumously (Burch, 2010), describes the methodology Burch developed for use in his own reconstructions of Eskimo societies and thus pays considerable attention to the process of collecting and evaluating oral history data.9 It is complemented by his paper “Toward a Sociology of the Prehistoric Inupiat” (Burch, 1988a), which lays out an approach developed to help archaeologists reconstruct prehistoric Eskimo societies in northwest Alaska. Each of these methodological works contains valuable lessons concerning the practice of ethnohistory. Last, it should also be mentioned that Burch’s (1984) editorial work on a special issue of Études/Inuit/Studies that focused on the Central Yup’ik Eskimos helped inspire new ethnohistorical research in southwest Alaska, a region in which he had no personal field expertise.

Lydia Black (1925–2007; Figure 12.10) is the final person whose ethnohistorical work chronologically must be noted here. Like VanStone, she made significant contributions in editing, annotating, and translating Russian source materials. Most of her efforts in that arena did not concern Alaska Eskimos (e.g., Black, 1983, 1987), but those that did were important, the best examples being The Journals of Iakov Netsvetov: The Yukon Years (Black, 1984a) and her paper “The Yup’ik of Western Alaska and Russian Contact” (Black, 1984b; see also Black, 1977, 1979, 1992). It could be argued that Black’s most influential publication in Alaska Eskimo ethnohistory was “The Daily Journal of Reverend Father Juvenal: A Cautionary Tale” (Black, 1981). It presented irrefutable evidence of dishonesty with historical records by the former U.S. Census agent Ivan Petroff and is a testament to the value of the ethnohistorical method for analyzing the accuracy and reliability of accounts about specific historical events (cf. Ray, 1974 [see also Black, 2004:17–19, 32–33 (notes 21–25, 30)]; Wright, 1995; Pratt, 1997, 2010b). It also highlighted the danger of assuming that secondary sources of information accurately represent original source materials. Sound ethnohistorical analyses are instead dependent on deliberate, critical reviews of the primary data sources for the topic being considered.

Four specific publication series that contributed significantly to Alaska Eskimo ethnohistory cannot be overlooked in a retrospective article of this sort. The unquestioned leader in this regard has been the Limestone Press. Established in 1972 under the editorial leadership of historian Richard Pierce (1918–2004), it has published over two dozen books of previously unavailable information in its Alaska History series, mostly related to the history of Russian America (e.g., Merck, 1980; Adams, 1982; Pierce, 1984, 1990; Khlebnikov, 1994). Less numerous but similarly important ethnohistorical sources have been published by the University of Alaska Press as part of the Rasmuson Library Historical Translations series (e.g., Holmberg, 1985; VanStone, 1988) and by the University of Toronto Press on behalf of the Arctic Institute of North America under the latter organization’s Anthropology of the North: Translations from Russian Sources series (e.g., Rudenko, 1961; Zagoskin, 1967).

Figure 12.10 Lydia T. Black at Korovin Bay, Atka Island, Alaska, summer 2003. Photo courtesy Patricia Petrivelli.

Thanks to the tireless productivity of James VanStone, numerous volumes of the Fieldiana: Anthropology series published by the Field Museum of Natural History in Chicago present valuable ethnohistorical studies of northern peoples and associated ethnographic and material culture collections, as well as translations of early Russian explorations of Alaska. Many of these studies are cited elsewhere in this paper.

Strictly speaking, some of the publications in these four series may not be ethnohistorical works, but collectively, they have substantially increased the source materials now available to students of Alaska Eskimo ethnohistory.

By 1980 more anthropologists were engaged in research concerning Alaska Eskimos than ever before, and several additional subfields of anthropology were establishing themselves in the state, most notably applied anthropology (Feldman et al., 2005) and subsistence management (e.g., Fall, 1990; Wheeler and Thornton, 2005). Considered together with research primarily ethnographic or sociocultural in nature (e.g., Fienup-Riordan, 1983; see also Burch, 2005)—and that originating from other disciplines (e.g., history of medicine and epidemic diseases; e.g., Fortuine, 1968, 1989)—these developments complicated the already difficult task of distinguishing ethnohistorical works from those more appropriately assigned to other anthropological subfields or methodologies. There is no easy or right way to make such determinations, so the works cited below as ethnohistorical examples were chosen somewhat selectively.

By the mid-1980s the topical area that had attained the highest degree of prominence in studies of Alaska Eskimo ethnohistory concerned ethnic group identification, boundaries, and interactions (e.g., Fienup-Riordan, 1984; Pratt, 1984a, 1984b; Shinkwin and Pete, 1984; see also Andrews and Koutsky, 1976; Andrews, 1989; Partnow, 1993; Burch and Mishler, 1995; Ganley, 1995), with most of the studies geographically focused on southwest Alaska. Interest in this topic was comparatively short-lived, however, and only a few related works have been completed in the past two decades (i.e., Schweitzer and Golovko, 1997; Crowell et al., 2001; Partnow, 2002; Pratt, 2009c, 2012; Ganley and Wheeler, 2012).

Other topics of inquiry to which ethnohistorical approaches have been profitably applied involved the impacts of historical epidemic diseases (e.g., Wolfe, 1982; Arndt, 1985; Dumond, 1996; Ganley, 1998; Crowell and Oozevaseuk, 2006), social change (e.g., Flanders, 1984; Fienup-Riordan, 1988), settlement, subsistence, and economic change (e.g., Koutsky, 1981–1982; Fienup-Riordan, 1982; Sheppard, 1983, 1986; Burch, 1985; Bockstoce, 1986, 2009; Pratt, 1990, 2001; Crowell, 1994; Lucier and VanStone, 1995; Arndt, 1996; Griffin, 1996, 2001; Morseth, 1997; Drozda, 2009), and demographic studies (e.g., Krupnik, 1994; Dumond, 1995; Pratt, 1997; Pratt et al., 2013).

This listing of works indicates that ethnohistory is still alive in Alaska Eskimo studies, but in reality, its regularly practicing members are probably fewer in number now than at any point since its florescence in the 1970s; little, if any, new blood seems to be entering the field’s scholarly gene pool. Thus, “genealogical” connections can be traced between the earlier generations of Alaska Eskimo ethnohistorians and some current practitioners, but the resulting scholarly lineage is now in threat of dying out. One explanation for this is that a majority of the individuals engaged in ethnohistorical research in Alaska during the past three decades have been employed in nonacademic positions. They typically do not have students to whom their ethnohistorical skills and interests can be imparted and so tend not to attract new practitioners to the field.

Ethnohistorical studies of non-Eskimo peoples in Alaska also have a long history (e.g., Osgood, 1937, 1940; Heizer, 1943; de Laguna, 1947; McKennan, 1959, 1965; Townsend, 1965; Loyens, 1966; VanStone, 1974; Schneider, 1976), and in contrast, their occurrence and number of practitioners has remained comparatively stable (e.g., Kan, 1985, 1989; Kari, 1986; Fall, 1987; Arndt, 1988, 1996; Ellanna and Balluta, 1992; Simeone, 1995, 1998, 2007; Pratt, 1998; Raboff, 2001; Kari and Fall, 2003; Mishler and Simeone, 2004; Thornton, 2004; Easton, 2007; Mishler, 2007; Borass and Peter, 2008; Dauenhauer et al., 2008; Fast, 2008).

For reasons that are not entirely clear, the blossoming of Alaska Eskimo ethnohistorical research witnessed during the 1970s and early 1980s (see VanStone, 1983b) has not been sustained. The concurrent development of symbolic and interpretive anthropology, with its emphasis on structuralist analysis (e.g., Sahlins, 1981), must have been one of the factors contributing to a movement away from historical approaches by many anthropologists. Also, in Alaska and elsewhere in the Arctic, the subdiscipline of sociocultural anthropology has undergone a change from historical and ethnohistorical studies to those focused primarily on applied research concerning contemporary communities (e.g., Davis, 1986) and a broad range of contemporary issues. The latter includes matters of law (e.g., Fienup-Riordan, 1990; Morrow and Pete, 1996), community relocation (e.g., Krupnik and Chlenov, 2007; Holzlehner, 2012), health (e.g., McNabb, 1990; Hedwig, 2009), and education (e.g., Lipka et al., 1998; Barnhardt and Kawagley, 1999). Among other things, this change underscores both a thinning and aging of the ranks of ethnologists and sociocultural anthropologists interested in the past, as opposed to contemporary issues. It compels me to end this discussion with something of a lament, with hope that it may serve as a sort of call to arms for like-minded colleagues.

The founding and second-generation scholars (de Laguna, Lantis, Oswalt, Ray, VanStone) whose contributions were discussed above were widely respected, highly productive, and very innovative. The rich and detailed data contained in their works should act as launching pads for new and related ethnohistorical studies, but that does not seem to be the case.

This apparent decline in the practice of ethnohistory also correlates to some extent with reduced consideration of the Russian-America period (with respect to Eskimo areas), the fur trade, culture contact and change, and similar topics that are heavily reliant on written historical records. Also, although notable exceptions exist (e.g., Harritt, 1995, 2010; Griffin, 1996, 2004; Dumond, 1998; Steffian and Saltonstall, 2001; Staley, 2009; Jensen, 2012), most archaeologists who work in Eskimo regions of Alaska remain focused on early prehistory (obsessed with antiquity). Thus, they face similar interpretive limitations to those Oswalt and VanStone recognized 45 years ago. This trend was previously noted by Don Dumond, who surmised that the general failure of archaeologists to search out and consider other lines of evidence in their work may partly be because “many archaeological specialists are certain that their discipline alone is so effective as a means of recovering prehistory that others can be essentially ignored” (Dumond, 1998:59–60). Judging by much of the Alaska research being published today, in all fields of anthropology, it appears that many of our younger colleagues also are not very familiar with early classics in Alaska history (e.g., Allen, 1887; Dall, 1870; Healy, 1887; Murdoch, 1892; Nelson, 1899; Stoney, 1900; Zagoskin, 1967). This particular type of knowledge is an essential foundation for ethnohistorians.

Similarly, although oral history has become a powerful factor in Alaska Eskimo research since about the early 1990s, that development has had its own drawbacks. I contend that it has helped move the research pendulum to a renewed fixation on quasi-romantic interpretations of the indigenous past—a trend that finds considerable public traction and is popular to some Alaska Native interests but also contributes to an erosion of thorough historical scholarship. Native oral history accounts are increasingly treated as if they are culturally and historically valid simply by virtue of their indigenous origins. Ironically, in Alaska, this may partly be an unexpected consequence of Burch’s (1991) seminal article “From Skeptic to Believer.” His strong assertion that oral history, used properly, is a reliable tool for scientific research attracted many disciples and intensified the focus on indigenous knowledge in Alaska research projects. But oral history research now being conducted with Alaska Eskimo populations often does not follow a rigorous methodology of the sort he advocated (e.g., Burch, 2010). Furthermore, although a substantial and topically rich body of Native oral history from earlier research is now housed in Alaska archives—but not available electronically—few anthropologists make serious efforts to access such records. Thus, another important hallmark of ethnohistory, archival research, may also be fading into obscurity.

These trends are suggestive of a progressive decline of interest in cultural history per se, which has negative implications for the future of Alaska Eskimo ethnohistory and perhaps for historically oriented studies of Inuit peoples generally. In Alaska, what indigenous peoples say about themselves and their pasts is too often granted primacy over any other source of information, even if the indigenous argument may be self-serving (e.g., Napolean, 1996). Many such works resound with the public and receive endorsements from social scientists, some of whom may view them collectively as an important and long-overdue step forward from the colonial past. But solid ethnohistorical work is neither quick nor easy, and the ethnicity of authorship should never be allowed to override expectations of scholarly rigor.

To close on a more thoughtful note, the process of researching and writing this paper has helped to remind me that our shared history as northern scholars is evoked by revisiting the important ideas and contributions of our predecessors. It is a history replete with remarkable scholarship at levels many of us will never attain but to which all of us can, and should, aspire. There is much work yet to be done in Alaska Eskimo ethnohistory, and if this essay spurs new efforts in that direction, it will have served a useful purpose.

I thank Igor Krupnik for inviting me to contribute to this volume and for the many helpful suggestions, insights, and critical comments he has offered throughout my work on this topic. Peter Schweitzer also provided thoughtful comments on a very early draft of this paper, and Robert Drozda helped me locate several important archival photographs. For assistance provided with other photographs used in this paper, I am also grateful to the following archivists: Sandra Johnston of the Alaska State Library; Rosemarie Speranza of the Alaska and Polar Regions Collections and Archives, University of Alaska Fairbanks; and Jason Flahardy of the University of Kentucky Archives.

1. William Nelson Fenton (1908–2005) was a Yale-trained historian who was a leader of studies of the Iroquois from the 1940s to the end of his long career in the 1990s. He worked for the Bureau of American Ethnology of the Smithsonian Institution and the New York State Museum in Albany. He was fluent in the Iroquois language and was adopted into the Hawk clan of the Seneca nation, the same clan that once adopted Lewis Henry Morgan.—Ed.

2. See Pratt (2009a) for detailed information about the resulting ANCSA 14(h)(1) program, including examples of associated site investigations and the data collection generated by the program’s implementation (which began in 1975 and is ongoing). Most of the comments that follow describing specific aspects of the program are derived from Pratt (2009b).

3. The ultimate deadline by which ANCSA 14(h)(1) claims had to be filed was December 31, 1976.

4. These parties consisted of the following: Ahtna, Inc.; Aleut Corporation; Bering Straits Native Corporation; Bristol Bay Native Corporation; Calista Corporation; Chugach Alaska Corporation; Doyon, Limited; and Koniag, Inc.

5. Numerous other AHP-CPSU publications (e.g., Schneider et al., 1980; Davis et al., 1981; Nelson et al., 1982) that had little or no relationship to ANCSA 14(h)(1) work were nevertheless produced as a direct result of NPS funding allocated by the U.S. Congress specifically for this program’s implementation. Most of them also contain ethnohistorical data.

6. These files constitute a rich resource for studies of the organizational and implementation history of the ANCSA 14(h)(1) Program. Particularly well-represented topics include disputes surrounding 14(h)(1) site eligibility decisions, federal interagency politics, and the marginalization of indigenous history in the United States (e.g., Pratt, 1994, 2009d; Miraglia, 2009).

7. Examples include Ernest S. Burch Jr. (e.g., Burch, 2005), James Kari (e.g., Kari, 2005), Herbert D. G. Maschner (e.g., Maschner et al., 1997), Craig Mishler (1995), and Anthony Woodbury (1999).

8. This was a rewrite of an earlier paper Burch had delivered in 1981 (see Burch, 1981b).

9. Burch may have begun working on this posthumously published paper as early as 1975; he presented a short version of it in 1981 and an expanded version in 1988 (Pratt, 2010a).

Ackerman, Robert E. 1970. “Archaeoethnology, Ethnoarchaeology, and the Problems of Past Cultural Patterning.” In Ethnohistory in Southwestern Alaska and the Southern Yukon: Method and Content, ed. M. Lantis, pp. 11–47. Lexington: University Press of Kentucky.

Adams, George R. 1982. Life on the Yukon, 1865–1867. Ed. R. A. Pierce. Kingston, ON: Limestone Press.

Allen, Henry T. 1887. Report of an Expedition to the Copper, Tanana, and Koyukuk Rivers, in the Territory of Alaska, in the Year 1885. Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office.

Andrews, Elizabeth F. 1977. Report on the Cultural Resources of the Doyon Region, Central Alaska. Volumes 1–2. Occasional Paper 5. Fairbanks: Anthropology and Historic Preservation, Cooperative Park Studies Unit, University of Alaska.

———. 1989. The Akulmiut: Territorial Dimensions of a Yup’ik Eskimo Society. Ph.D. diss., Department of Anthropology, University of Alaska Fairbanks.

Andrews, Elizabeth, and Kathryn Koutsky. 1976. “Ethnohistory of the Kaltag Portage, West-Central Alaska.” In Proceedings of the First Conference on Scientific Research in the National Parks, New Orleans, Louisiana, November 9–12, 1976, ed. R. M. Linn, pp. 921–924. Transactions and Proceedings Series 5. Washington, D.C.: National Park Service.

Arndt, Katherine L. 1985. “The Russian-American Company and the Smallpox Epidemic of 1835 to 1840.” Paper presented at the 12th Annual Meeting of the Alaska Anthropological Association, Anchorage, March 2.

———. 1988. Russian Relations with the Stikine Tlingit, 1833–1867. Alaska History, 3(1): 27–43.

———. 1996. Dynamics of the Fur Trade on the Middle Yukon River, Alaska, 1839 to 1868. Ph.D. diss., Department of Anthropology, University of Alaska Fairbanks.

Barber, Russell J., and Frances F. Berdan. 1998. The Emperor’s Mirror: Understanding Cultures through Primary Sources. Tucson: University of Arizona Press.

Barnhardt, Ray, and Oscar Kawagley. 1999. “Education Indigenous to Place: Western Science Meets Indigenous Reality.” In Ecological Education in Action, ed. G. Smith and D. Williams, pp. 117–140. New York: SUNY Press.

Birket-Smith, Kaj. 1941. “Early Collections from the Pacific Eskimo.” In Ethnographical Studies, Published on the Occasion of the Centenary of the Ethnographical Department, National Museum, pp. 121–163. Nationalmuseets Skrifter, Etnografisk Raekke 1. Copenhagen: Gyldednalske.

———. 1953. The Chugach Eskimo. Nationalmuseets Skrifter, Etnografisk Række 6. Copenhagen: Nationalmuseets Publikationsfond.

Birket-Smith, Kaj, and Frederica de Laguna. 1938. The Eyak Indians of the Copper River Delta. Copenhagen: Levin and Munksgaard.

Black, Lydia T. 1977. The Konyag (The Inhabitants of the Island of Kodiak) by Iosaf [Bolotov], 1794–1799, and by Gideon, 1804–1807. Arctic Anthropology, 14(2):79–108.

———. 1979. “The Question of Maps: Exploration of the Bering Sea in the Eighteenth Century.” In The Sea in Alaska’s Past: Conference Proceedings, pp. 6–50. History and Archaeology Publications Series 25. Anchorage: Office of History and Archaeology, Alaska Division of Parks.

———. 1981. The Daily Journal of Reverend Father Juvenal: A Cautionary Tale. Ethnohistory, 28(1):33–58.

———. 1983. Atkha: An Ethnohistory of the Western Aleutians. Kingston, ON: Limestone Press.

———, trans. 1984a. The Journals of Iakov Netsvetov: The Yukon Years, 1844–1863. With notes and additional material by Lydia T. Black. Ed. R. A. Pierce. Kingston, ON: Limestone Press.

———. 1984b. The Yup’ik of Western Alaska and Russian Impact. Études/Inuit/Studies, 8(Suppl.):21–43.

———. 1987. Whaling in the Aleutians. Études/Inuit/Studies, 11(2):7–50.

———. 1992. The Russian Conquest of Kodiak. Anthropological Papers of the University of Alaska, 24(1–2):165–182.

———. 2004. Russians in Alaska, 1732–1867. Fairbanks: University of Alaska Press.

Bockstoce, John R. 1986. Whales, Ice and Men: The History of Whaling in the Western Arctic. Seattle: University of Washington Press.

———. 2009. Furs and Frontiers in the Far North: The Contest among Native and Foreign Nations for the Bering Strait Fur Trade. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Borass, Alan, and Donita Peter. 2008. The Role of Beggesh and Beggesha in Precontact Dena’ina Culture. Alaska Journal of Anthropology, 6(1–2):211–224.

Burch, Ernest S., Jr. 1974. Eskimo Warfare in Northwest Alaska. Anthropological Papers of the University of Alaska, 16(2):1–14.

———. 1975. Inter-regional Transportation in Traditional Northwest Alaska. Anthropological Papers of the University of Alaska, 17(2):1–11.

———. 1976a. Overland Travel Routes in Northwest Alaska. Anthropological Papers of the University of Alaska, 18(1):1–10.

———. 1976b. “The ‘Nunamiut’ Concept and the Standardization of Error.” In Contributions to Anthropology: The Interior Peoples of Northern Alaska, ed. E. S. Hall Jr., pp. 52–97. Archaeological Survey of Canada Paper 49. Ottawa: National Museum of Man.

———. 1979. Indians and Eskimos in North Alaska, 1816–1977: A Study in Changing Ethnic Relations. Arctic Anthropology, 16(2):123–151.

———. 1980. “Traditional Eskimo Societies in Northwest Alaska.” In Alaska Native Culture and History, ed. Y. Kotani and W. B. Workman, pp. 253–304. Senri Ethnological Series 4. Osaka, Japan: National Museum of Ethnology.

———. 1981a. The Traditional Eskimo Hunters of Point Hope, Alaska: 1800–1875. Barrow: North Slope Borough.

———. 1981b. “Studies of Native History as a Contribution to Alaska’s Future.” Paper presented at the 32nd Alaska Science Conference, Fairbanks, August 25.

———, ed. 1984. The Central Yup’ik Eskimos. Études/Inuit/Studies, 8(Suppl.).

———. 1985. The Subsistence Economy of Kivalina, Alaska: A Twenty-Year Comparison of Fish and Game Harvests. Technical Paper 128. Juneau: Division of Subsistence, Alaska Department of Fish and Game.

———. 1988a. “Toward a Sociology of the Prehistoric Inupiat: Problems and Prospects.” In The Late Prehistory of Alaska’s Native People, ed. R. D. Shaw, R. K. Harritt, and D. E. Dumond, pp. 1–16. Aurora: Alaska Anthropological Association Monograph Series 4. Anchorage: Alaska Anthropological Association.

———. 1988b. “War and Trade.” In Crossroads of Continents: Cultures of Siberia and Alaska, ed. W. W. Fitzhugh and A. Crowell, pp. 227–240. Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution Press.

———. 1998a. The Iñupiaq Eskimo Nations of Northwest Alaska. Fairbanks: University of Alaska Press.

———. 1998b. Boundaries and Borders in Early Contact North-Central Alaska. Arctic Anthropology, 35(2):19–48.

———. 1991. From Skeptic to Believer: The Making of an Oral Historian. Alaska History, 6(1): 1–16.

———. 2005. Alliance and Conflict: The World System of the Iñupiaq Eskimos. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press.

———. 2006. Social Life in Northwest Alaska: The Structure of Iñupiaq Eskimo Nations. Fairbanks: University of Alaska Press.

———. 2010. The Method of Ethnographic Reconstruction. Alaska Journal of Anthropology, 8(2):121–140.

Burch, Ernest S., Jr., and Thomas C. Correll. 1972. “Alliance and Conflict: Inter-regional Relations in North Alaska.” In Alliance in Eskimo Society, ed. L. Geumple, pp. 17–39. Proceedings of the American Ethnological Society, 1971 (Supplement). Seattle: University of Washington Press.

Burch, Ernest S., Jr., Eliza Jones, Hannah P. Loon, and Lawrence D. Kaplan. 1999. The Ethnogenesis of the Kuuvaum Kaŋiaġmiut. Ethnohistory, 46(2):291–327.

Burch, Ernest S., Jr., and Craig W. Mishler. 1995. The Di’hąįį Gwich’in: Mystery People of Northern Alaska. Arctic Anthropology, 32(1):147–172.

Campbell, John Martin. 1998. North Alaska Chronicle: Notes from the End of Time: The Simon Paneak Drawings. Santa Fe: Museum of New Mexico Press.

———, ed. 2004. In a Hungry Country: Essays by Simon Paneak. Fairbanks: University of Alaska Press.

Chance, Norman A. 1960. Culture Change and Integration: An Eskimo Example. American Anthropologist, 62(6):1028–1044.

Cook Inlet Historic Sites Project. 1975. Cook Inlet Region Inventory of Native Historic Sites and Cemeteries. Prepared by Gregg Brelsford. Anchorage: Cook Inlet, Inc. [Copy on file, Bureau of Indian Affairs, ANCSA Office, Anchorage.]

Crowell, Aron L. 1994. “Koniag Eskimo Poisoned-Dart Whaling.” In Anthropology of the North Pacific Rim, ed. W. W. Fitzhugh and V. Chaussonnet, pp. 217–242. Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution Press.

Crowell, Aron L., Gordon L. Pullar, and Amy F. Steffian. 2001. Looking Both Ways: Heritage and Identity of the Alutiiq People. Fairbanks: University of Alaska Press.

Crowell, Aron, and Estelle Oozevaseuk. 2006. The St. Lawrence Island Famine and Epidemic, 1878–80: A Yupik Narrative in Cultural and Historical Context. Arctic Anthropology, 43(1):1–19.

Dall, William H. 1870. Alaska and Its Resources. Boston: Lee and Shepard.

Dauenhauer, Richard, Nora Marks Dauenhauer, and Lydia Black. 2008. Anooshi Lingit Aani Ka, Russians in Tlingit America: The Battles of Sitka 1802 and 1804. Seattle: University of Washington Press.

Davis, Craig W., Dana C. Linck, Kenneth M. Schoenberg, and Harvey M. Shields. 1981. Slogging, Humping and Mucking through the NPR-A: An Archeological Interlude. Volumes 1–5. Occasional Paper 25. Fairbanks: Anthropology and Historic Preservation, Cooperative Park Studies Unit, University of Alaska.

Davis, Nancy Yaw. 1986. “Earthquake, Tsunami, Resettlement and Survival in Two North Pacific Alaskan Native Villages.” In Natural Disasters and Cultural Responses, ed. A. Oliver-Smith, pp. 123–154. Studies in Third World Societies 36. Williamsburg, VA: Department of Anthropology, College of William and Mary.

de Laguna, Frederica. 1932. A Comparison of Eskimo and Paleolithic Art (1). American Journal of Archaeology, 36(4):477–511.

———. 1933. A Comparison of Eskimo and Paleolithic Art (2). American Journal of Archaeology, 38(1):77–107.

———. 1947. The Prehistory of Northern North America as Seen from the Yukon. Memoirs of the Society for American Archaeology 3. Menasha, WI: Society for American Archaeology.

———. 1956. Chugach Prehistory: The Archaeology of Prince William Sound. University of Washington Publications in Anthropology 13. Seattle: University of Washington Press.

Drozda, Robert M. 1995. “ ‘They Talked of the Land with Respect’: Interethnic Communication in the Documentation of Historical Places and Cemetery Sites.” In When Our Words Return: Writing, Hearing, and Remembering Oral Traditions of Alaska and the Yukon, ed. P. Morrow and W. Schneider, pp. 98–122. Logan: Utah State University Press.

———. 2009. Nunivak Island Subsistence Cod, Red Salmon and Grayling Fisheries: Past and Present. Final Report (Study 05-353). Fairbanks: Office of Subsistence Management, Fisheries Resource Monitoring Program, Fish and Wildlife Service.

Dumond, Don E. 1995. Demographic Effects of European Expansion: A Nineteenth-Century Native Population on the Alaska Peninsula. University of Oregon Anthropological Papers 35. Eugene: University of Oregon.

———. 1996. “Poison in the Cup: The South Alaskan Smallpox Epidemic of 1835.” In Chin Hills to Chiloquin: Papers Honoring the Versatile Career of Theodore Stern, ed. D. E. Dumond, pp. 117–129. University of Oregon Anthropological Papers 52. Eugene: University of Oregon.

———. 1998. The Archaeology of Migrations: Following the Fainter Footsteps. Arctic Anthropology, 35(2):59–76.

Dumond, Don E., and James W. VanStone. 1995. Paugvik: A Nineteenth-Century Native Village on Bristol Bay, Alaska. Fieldiana: Anthropology, n.s., 24. Chicago: Field Museum of Natural History.

Easton, Norman Alexander. 2007. King George Got Diarrhea: The Yukon-Alaska Boundary Survey, Bill Rupe, and the Scottie Creek Dineh. Alaska Journal of Anthropology, 5(1):95–118.

Ellanna, Linda J., and Andrew Balluta. 1992. Nuvendaltin Quht’ana: The People of Nondalton. Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution Press.

Fall, James A. 1987. The Upper Inlet Tanaina: Patterns of Leadership among an Alaska Athabaskan People, 1741–1918. Anthropological Papers of the University of Alaska, 21(1–2):1–80.

———. 1990. The Division of Subsistence of the Alaska Department of Fish and Game: An Overview of Its Research and Findings. Arctic Anthropology, 27(2):68–92.

Fast, Phyllis A. 2008. The Volcano in Athabascan Oral Narratives. Alaska Journal of Anthropology, 6(1–2):131–140.

Fenton, William N. 1940. “Problems Arising from the Historic Northeastern Position of the Iroquois.” In Essays in Historical Anthropology of North America, ed. J. H. Steward, pp. 159–251. Smithsonian Miscellaneous Publications 100. Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution.

———. 1941. Iroquois Suicide: A Study in the Stability of a Culture Pattern. Bureau of American Ethnology Bulletin 128(14). Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution.

———. 1952. The Training of Historical Ethnologists in America. American Anthropologist, 54(3):328–339.

———. 1962. Ethnohistory and Its Problems. Ethnohistory, 9(1):1–23.

———. 1966. Field Work, Museum Studies, and Ethnohistorical Research. Ethnohistory, 13(1–2): 71–85.

Fienup-Riordan, Ann. 1982. Navarin Basin Sociocultural Baseline Analysis. Bureau of Land Management, Alaska Outer Continental Shelf Socioeconomics Studies Program, Technical Report 70. Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office.

———. 1983. The Nelson Island Eskimo: Social Structure and Ritual Distribution. Anchorage: Alaska Pacific University Press.

———. 1984. Regional Groups on the Yukon-Kuskokwim Delta. Études/Inuit/Studies, 8(Suppl.): 63–93.

———, ed. 1988. The Yup’ik Eskimos: As Described in the Travel Journals and Ethnographic Accounts of John and Edith Kilbuck, 1885–1900. Kingston, ON: Limestone Press.

———. 1990. “The Yupiit Nation: Eskimo Law and Order.” In Eskimo Essays, pp. 192–220. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press.

———. 1996. The Living Tradition of Yup’ik Masks: Agayuliyararput, Our Way of Making Prayer. Seattle: University of Washington Press.

———, ed. 1999. Where the Echo Began: And Other Oral Traditions from Southwestern Alaska Recorded by Hans Himmelheber. Trans. K. Vitt and E. Vitt. Fairbanks: University of Alaska Press.

Feldman, Kerry D., Steve J. Langdon, and David C. Natcher. 2005. Northern Engagement: Alaskan Society and Applied Cultural Anthropology, 1973–2003. Alaska Journal of Anthropology, 3(1):121–155.

Fitzhugh, William W., and Susan A. Kaplan. 1982. Inua: The Spirit World of the Bering Sea Eskimo. Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution Press.

Flanders, Nicholas A. 1984. Religious Conflict and Social Change: A Case from Western Alaska. Études/Inuit/Studies, 8(Suppl.):141–157.

Fortuine, Robert. 1968. The Health of the Eskimos: A Bibliography, 1857–1967. Hanover, NH: Dartmouth College Libraries.

———. 1989. Chills and Fever: Health and Disease in the Early History of Alaska. Fairbanks: University of Alaska Press.

Ganley, Matt. 1995. The Malemiut of Northwest Alaska: A Study in Ethnonymy. Études/Inuit/Studies, 19(1):103–118.

———. 1998. The Dispersal of the 1918 Influenza Virus on the Seward Peninsula, Alaska. International Journal of Circumpolar Health, 57(Suppl. 1):247–251.

———. 2009. “Luck and the Art of Leaving No Stone Unturned: The Search for Bear Rock Monument.” In Chasing the Dark: Perspectives on Place, History and Alaska Native Land Claims, ed. K. L. Pratt, pp. 230–240. Shadowlands, Volume 1. Anchorage: Bureau of Indian Affairs, ANCSA Office.

Ganley, Matt, and Polly C. Wheeler. 2012. The Place Not Yet Subjugated: Prince William Sound, 1770–1800. Arctic Anthropology, 49(2):113–127.

Giddings, J. Louis. 1952. The Arctic Woodland Culture of the Kobuk River. University Museum Monograph 8. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania.

———. 1956. Forest Eskimos: An Ethnographic Sketch of Kobuk River People in the 1880s. University of Pennsylvania, Museum Bulletin, 20(2):1–55.

———. 1961. Kobuk River People. Studies of Northern Peoples 1. College, Alaska: Department of Anthropology and Geography, University of Alaska.

Griffin, Dennis. 1996. A Culture in Transition: A History of Acculturation and Settlement Near the Mouth of the Yukon River, Alaska. Arctic Anthropology, 33(1):98–115.

———. 2001. Nunivak Island, Alaska: A History of Contact and Trade. Alaska Journal of Anthropology, 1(1):51–68.

———. 2004. Ellikarrmiut: Changing Lifeways in an Alaska Community. Aurora: Alaska Anthropological Association Monograph Series 7. Anchorage: Alaska Anthropological Association.

Haakanson, Sven D., Jr. and Amy F. Steffian, eds. 2009. Giinaquq—Like a Face: Sugpiaq Masks of the Kodiak Archipelago. Fairbanks: University of Alaska Press.

Harkin, Michael E. 2010. Ethnohistory’s Ethnohistory: Creating a Discipline from the Ground Up. Social Science History, 34(2):113–128.

Harritt, Robert K. 1995. “The Development and Spread of the Whale Hunting Complex in Bering Strait: Retrospective and Prospects.” In Hunting the World’s Largest Animals: Native Whaling in the Western Arctic and Subarctic, ed. A. P. McCartney, pp. 33–51. Studies in Whaling 3, Occasional Paper 36. Edmonton, AB: Canadian Circumpolar Institute.

———. 2010. Variations of Late Prehistoric Houses in Coastal Northwest Alaska: A View from Wales. Arctic Anthropology, 47(1):57–70.

Healy, Michael A. 1887. Report of the Cruise of the Revenue Marine Steamer Corwin in the Arctic Ocean in the Year 1885. Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office.

Heizer, Robert F. 1943. Aconite Poison Whaling in Asia and Alaska: An Aleutian Transfer to the New World. Bureau of American Ethnology Bulletin 133(24). Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution.

Hedwig, Travis. 2009. The Boundaries of Inclusion for Iñupiat Experiencing Disability in Alaska. Alaska Journal of Anthropology, 7(1):123–138.

Holmberg, Heinrich Johan. 1985. Holmberg’s Ethnographic Sketches. Trans. F. Jaensch. Ed. M. W. Falk. Rasmuson Library Historical Translations Series 1. Fairbanks: University of Alaska Press.

Holzlehner, Tobias. 2012. “Somehow, Something Broke inside the People”: Demographic Shifts and Community Anomie in Chukotka, Russia. Alaska Journal of Anthropology, 10(1–2): 1–16.

Hughes, Charles C. 1960. An Eskimo Village in the Modern World. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

Jensen, Anne M. 2012. The Material Culture of Iñupiat Whaling: An Ethnographic and Ethnohistorical Perspective. Arctic Anthropology, 49(2):143–161.

Kan, Sergei. 1985. Russian Orthodox Brotherhoods among the Tlingit: Missionary Goals and Native Response. Ethnohistory, 32(3):196–222.

———. 1989. Symbolic Immortality: The Tlingit Potlatch of the Nineteenth Century. Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution Press.

Kari, James. 1986. Tatl’ahwt’aenn Nenn’: The Headwaters People’s Country; Narratives of the Upper Ahtna Athabaskans. Fairbanks: Alaska Native Language Center, University of Alaska Fairbanks.

———. 2005. “Report on Traditional Cultural Properties for Sparrevohn Long Range Radar Site (Lime Village Vicinity).” Report prepared for Cultural Heritage Studies, Environment and Natural Resources Institute, University of Alaska Anchorage.

Kari, James, and James A. Fall. 2003. Shem Pete’s Alaska: The Territory of the Upper Cook Inlet Dena’ina. 2nd ed. Fairbanks: University of Alaska Press.

Khlebnikov, Kiril T. 1994. Notes on Russian America: Parts II—V: Kad’iak, Unalashka, Athka, The Pribylovs. Compiled by R. G. Liapunova and S. G. Fedorova. Trans. M. Ramsay. Ed. R. A. Pierce. Kingston, ON: Limestone Press.

Koutsky, Kathryn. 1981–1982. Early Days on Norton Sound and Bering Strait: An Overview of Historic Sites in the BSNC Region. Volumes 1–8. Occasional Paper 29. Fairbanks: Anthropology and Historic Preservation, Cooperative Park Studies Unit, University of Alaska.

Krech, Shepard. 1990. American Indian Ethnohistory: Recent Contributions by Three Historians. Reviews in Anthropology, 15:91–103.

———. 2006. Bringing Linear Time Back In. Ethnohistory, 53(3):567–593.

Krupnik, Igor. 1994. “Siberians” in Alaska: The Siberian Eskimo Contribution to Alaskan Population Recoveries, 1880–1940. Études/Inuit/Studies, 18(1–2):49–80.

Krupnik, Igor, and Michael A. Chlenov. 2007. The End of “Eskimo Land”: Yupik Relocations in Chukotka, 1958–1959. Études/Inuit/Studies, 31(1–2):59–81.

Lantis, Margaret. 1938a. The Mythology of Kodiak Island, Alaska. Journal of American Folklore, 51(200):123–172.

———. 1938b. The Alaskan Whale Cult and Its Affinities. American Anthropologist, 40(3): 438–464.

———. 1939. Alaskan Eskimo Ceremonialism. Ph.D. diss., University of California, Berkeley.

———. 1940. Note on the Alaskan Whale Cult and Its Affinities. American Anthropologist, 42(2):366–368.

———. 1946. The Social Culture of the Nunivak Eskimo. Transactions of the American Philosophical Society, n.s., 35(3):153–323.

———. 1947. Alaskan Eskimo Ceremonialism. Seattle: University of Washington Press.

———. 1959. Folk Medicine and Hygiene: Lower Kuskokwim and Nunivak-Nelson Island Areas. Anthropological Papers of the University of Alaska, 8(1):1–75.

———, ed. 1970a. Ethnohistory in Southwestern Alaska and the Southern Yukon: Method and Content. Lexington: University Press of Kentucky.

———. 1970b. “The Aleut Social System, 1750 to 1810, from Early Historical Sources.” In Ethnohistory in Southwestern Alaska and the Southern Yukon: Method and Content, ed. M. Lantis, pp. 139–301. Lexington: University Press of Kentucky.

———. 1970c. “The Methodology of Ethnohistory.” In Ethnohistory in Southwestern Alaska and the Southern Yukon: Method and Content, ed. M. Lantis, pp. 1–10. Lexington: University Press of Kentucky.

———. 1998. On “History” and James W. VanStone. Arctic Anthropology, 35(2):6–7.

Lipka, Jerry, Gerald V. Mohatt, and the Ciulistet Group. 1998. Transforming the Culture of Schools: Yup’ik Eskimo Examples. Mahwah, NY: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Loyens, William J. 1966. The Changing Culture of the Nulato Koyukon Indians. Ph.D. diss., University of Wisconsin, Madison.

Lucier, Charles V., and James W. VanStone. 1987. An Iñupiaq Autobiography. Études/Inuit/Studies, 11(1):149–172.

———. 1991a. The Traditional Oil Lamp among the Kangigmiut and Neighboring Iñupiaq of Kptzebue Sound, Alaska. Arctic Anthropology, 28(2):1–14.

———. 1991b. Winter and Spring Fast Ice Seal Hunting by Kangiġmiut and Other Iñupiat of Kotzebue Sound, Alaska. Études/Inuit/Studies, 15(1):29–49.

———. 1992. Historic Pottery of the Kotzebue Sound Iñupiat. Fieldiana: Anthropology, n.s., 18. Chicago: Field Museum of Natural History.

———. 1995. Traditional Beluga Drives of the Iñupiat of Kotzebue Sound, Alaska. Fieldiana: Anthropology, n.s., 25. Chicago: Field Museum of Natural History.

Lucier, Charles V., James W. VanStone, and Della Keats. 1971. Medical Practices and Human Anatomical Knowledge among the Noatak Eskimos. Ethnology, 10(3):251–264.

Maschner, Herbert D. G., James W. Jordan, Brian W. Hoffman, and Tina M. Dochat. 1997. The Archaeology of the Lower Alaska Peninsula. Report 4. Madison: Laboratory of Arctic and North Pacific Archaeology, University of Wisconsin.

Mason, Lynn D. 1975. Epidemiology and Acculturation: Ecological and Economic Adjustments to Disease among the Kuskowagamiut Eskimos of Alaska. Western Canadian Journal of Anthropology, 4(3):35–62.

Mason, Owen K. 2012. Memories of Warfare: Archaeology and Oral History in Assessing the Conflict and Alliance Model of Ernest S. Burch. Arctic Anthropology, 49(2):72–91.

McClellan, Catherine. 1970. “Indian Stories about the First Whites in Northwestern America.” In Ethnohistory in Southwestern Alaska and the Southern Yukon: Method and Content, ed. M. Lantis, pp. 103–133. Lexington: University of Kentucky Press.

McKennan, Robert A. 1959. The Upper Tanana Indians. Yale University Publications in Anthropology 55. New Haven, CT: Yale University.

———. 1965. The Chandalar Kutchin. Arctic Institute of North America Technical Paper 17. Montreal: Arctic Institute of North America.

McNabb, Steven. 1990. Native Health Status and Native Health Policy: Current Dilemma at the Federal Level. Arctic Anthropology, 27(1):20–35.

Merck, Carl Heinrich. 1980. Siberia and Northwestern America, 1788–1792: The Journal of Carl Heinrich Merck, Naturalist with the Russian Scientific Expedition Led by Captain Joseph Billings and Gavriil Sarychev. Trans. F. Jaensch. Ed. R. A. Pierce. Kingston, ON: Limestone Press.

Michael, Henry N., and James W. VanStone, eds. 1983. Cultures of the Bering Sea Region: Papers from an International Symposium. New York: International Research and Exchanges Board.

Miraglia, Rita M. 2009. “The Chugach Smokehouse: A Case of Mistaken Identity.” In Chasing the Dark: Perspectives on Place, History and Alaska Native Land Claims, ed. K. L. Pratt, pp. 250–259. Shadowlands, Volume 1. Anchorage: Bureau of Indian Affairs, ANCSA Office.

Mishler, Craig. 1995. Neerihiinjìk: We Traveled from Place to Place: The Gwich’in Stories of Johnny and Sarah Frank. Fairbanks: Alaska Native Language Center, University of Alaska Fairbanks.

———. 2007. Historical Demography and Genealogy: The Decline of the Northern Kenai Peninsula Dena’ina. Alaska Journal of Anthropology, 5(1):61–81.

Mishler, Craig, and William E. Simeone. 2004. Han, People of the River: Hän Hwëch’in. Fairbanks: University of Alaska Press.

Morrow, Phyllis, and Mary C. Pete. 1996. “Cultural Adoption on Trial: Cases from Southwestern Alaska.” In Law & Philosophy, Volume 8, ed. R. Kuppe and R. Potz, pp. 243–259. Dordrecht, Netherlands: Kluwer Law International.

Morseth, Michele C. 1997. Twentieth-Century Changes in Beluga Whale Hunting and Butchering by the Kaŋiġmiut of Buckland, Alaska. Arctic, 50(3):241–266.

Murdoch, John. 1892. Ethnological Results of the Point Barrow Expedition. In Ninth Annual Report of the Bureau of Ethnology to the Secretary of the Smithsonian Institution Years, 1887–’88, pp. 19–441. Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office.

Napolean, Harold. 1996. Yunyaraq: The Way of the Human Being. Fairbanks: Alaska Native Knowledge Network.

Nash, Phileo. 1988. “Twentieth-Century United States Government Agencies.” In Handbook of North American Indians, ed. William C. Sturtevant. Volume 4: History of Indian-White Relations, ed. Wilcomb E. Washburn, pp. 264–275. Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution Press.