For those who attempt to document the enduring presence of northern Native peoples and their histories, the debt to past generations of researchers and teachers is profound. The accumulated knowledge left behind by these Native and non-Native scholars took many forms: oral and written; scientific and general; photographic and artistic, or inscribed upon the landscape itself.

Both present and past scholars are linked together through our common purpose. Sometimes, the contributions of past scholars are mere fragments, slender postcards from the past. At other times, these assemblies of tangible and intangible offerings are astounding in their depth, breadth, and comprehensive character. Often, there are phenomenal publications, the joint efforts of Native and non-Native colleagues. In Alaska, for example, there are such “ancestors” as Ernest “Tiger” Burch, Bobby Howley Sr., and Herbert Anungazuk; Susan Fair, Gideon Barr, and Edgar Ningeolook; David Hopkins and Gideon Barr; and Charles Campbell Hughes, Richard Oktokiyok, and Leonard Nowpakahok. The collaboration of these Native and non-Native research team members attests to northern peoples’ ongoing presence. Each reminds us of the imperative to share and return what has been learned.

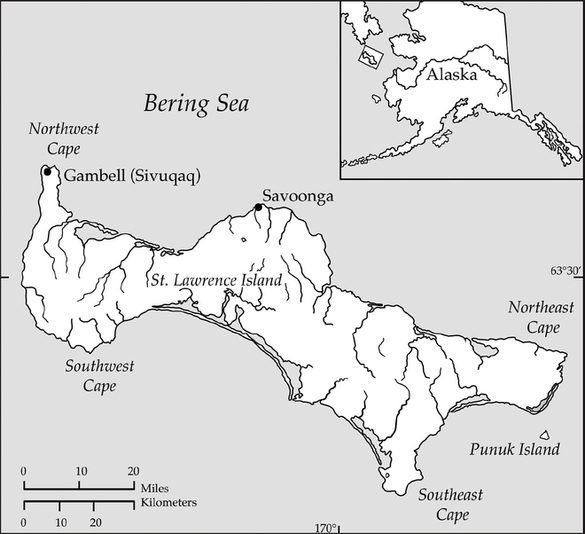

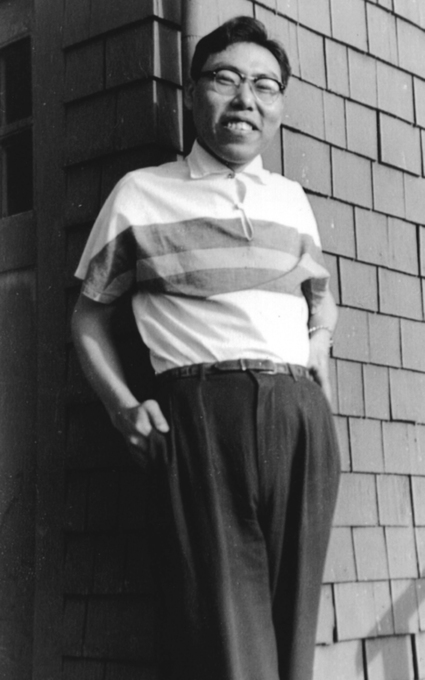

Some have benefitted directly from the advice and support of an ancestor. In my case, one of these predecessors was my mentor. In this context, I introduce the background and contributions of Charles Campbell Hughes (1929–1997; Figure 13.1). His concern was significant community change and its effect upon psychosocial behavior in the Yupik community of Sivuqaq (referred to generally as Gambell) on St. Lawrence Island, Alaska (Figure 13.2). He was one of a very few people to travel to St. Lawrence Island, Alaska, between 1912 and the 1950s to carry out anthropological research.1

Hughes’s approach to research modeled certain methods that others later adopted. Among these was the significant use of key “informants” by Hughes and his first wife and research partner, Jane M. Murphy, who accompanied him. Another of Hughes’s trademark methods was the careful collection of extensive life histories, family health, and mortality records. Hughes focused especially on individual life experiences, livelihoods, and interactions documented in a single contemporary village, Sivuqaq (Gambell). A third element was the decision to conduct lengthy field research—almost 15 months—in a single location. Previously, few had spent an extended period collecting data in a Native Alaskan village. The objective was to produce a comprehensive ethnography while focusing on certain specific characteristics of the village residents. Finally, Hughes’s use of key informants suggests the practice of building research partnerships with Native knowledge experts.

Figure 13.1 Charles Campbell Hughes, 1929–1997. Photo ca. 1995; courtesy Leslie Hughes.

I propose that during their residence in Gambell, the Hugheses, through their engagement in community level participation, offered an example that anticipated a research model that would later become an accepted practice. Hughes was followed soon after in this approach by James VanStone (1962) and others. But the work of Charles Hughes and Jane Murphy in Gambell in the mid-1950s served as a forerunner for many aspects of this type of research.

My tie to Charles Hughes stemmed from my own research on St. Lawrence Island some 30 years after Hughes’s work (Figure 13.3). Fortunately, I met him and benefitted both from his master’s research, written while he was a predoctoral student at Cornell University, and from his field study on the island among the Sivuqaghmiit, the people of Gambell, in 1954–1955.

Hughes’s research was built on linked generations of Native and non-Native scholarship and certain special relationships. He was especially indebted to his advisor, Alexander Hamilton Leighton, and Leighton’s first wife, Dorothea Cross Leighton. His efforts were also significantly aided in the field by assistance from his own wife, Jane, and by the willing cooperation of several Gambell extended families, including the Aningayou, Nowpakahok, Oktokiyok, Silook, and Slwooko families. Upon his death, Hughes left behind not only his publications about St. Lawrence Island life but the full body of his original research among the Sivuqaghmiit.

Figure 13.2 St. Lawrence Island and the Bering Strait area. Compiled by Marcia Bakry, Smithsonian Institution.

In reviewing Hughes’s contributions, I have been impressed by three things: first, the sheer volume of Hughes’s research about the Sivuqaghmiit; second, the web of scholarly and Native Elder ancestry that embraced him and that he represented through his work; and third, his personal generosity. I corresponded with Hughes briefly in the mid-1980s, and he later joined my doctoral committee long distance.2 In 1985, Hughes lent me, a graduate student with whom he had little previous acquaintance, his copious Gambell field notes, more than 5,000 typewritten pages. Anthropologist Igor Krupnik noted that he, too, had benefitted from Hughes’s generosity. In 1991, he met Hughes for the first time, and soon after Hughes sent him Gambell family genealogies from his 1950s fieldwork. Krupnik recalled Hughes as a “remarkably pleasant person, warm and caring in his attitude to a younger colleague” (I. Krupnik, National Museum of Natural History, personal communication, July 12, 2013). Perhaps Hughes’s kind gestures were modeled after similar acts of generosity by Alexander Leighton, Hughes’s Ph.D. advisor, when Hughes embarked on his own research. My encounters with Hughes echo the words of two of his contemporaries, who described him as a thoughtful, caring, and extremely hardworking man (Ronald Simons, personal communication, June 12, 2013; Marc-Adélard Tremblay and Colette Tremblay, personal communication, October 6, 2012).

Figure 13.3 The “old village” of Gambell as seen from the beach, with a whale jawbone and drying walrus hide in the foreground, 1997. Photo by Carol Zane Jolles.

Charles Hughes’s work in the Arctic developed generally within the realm of culture and personality studies. More particularly, it was a direct extension of Hughes’s interest in relationships that emerge from a community’s cultural environment, its physical environment, and the effects upon personality formation that derive from these. Charles Hughes’s development as a cultural anthropologist began informally during his youth and continued more directly once he entered college. I begin, then, with Hughes’s own description of his background.

Charles Campbell Hughes was born in 1929 in Salmon, Idaho. In his autobiographical statement at the opening of his master’s thesis (1953), he wrote that he was brought up in the western United States and had lived in several Rocky Mountain communities during his youth.3 He attended high school in Denver, Colorado, and it was there that he met Jane Ellen Murphy. After high school graduation, Murphy entered Phillips College in Oklahoma, and Hughes went to Boston to attend Harvard on a National Scholarship.4

Hughes entered Harvard in 1947. There he soon came under the influence of Clyde Kluckhohn (1905–1960), a highly respected cultural anthropologist, known for his focus on human behavior and social relations, his development of a theory of culture, his humanism, and his values orientation theory (Parsons and Vogt, 1962). Kluckhohn’s theories suggested that cross-cultural understanding and communication could be facilitated by analyzing a given culture’s orientation to five key aspects of human life: human nature, man-nature relationship, time, activity, and social relations (Kluckhohn, 1951). Kluckhohn had carried out much of his work in the American Southwest, focusing especially on psychosocial behavior and culture as represented by members of the Navajo Nation (Kluckhohn, 1939, 1944, 1949a, 1949b, 1951; Kluckhohn and Leighton, 1946; Leighton and Kluckhohn, 1947). With Kluckhohn as his undergraduate advisor, Hughes graduated magna cum laude from Harvard in 1951, having written his senior honors thesis on Navajo Christian conversion (Hughes, 1951). As Hughes neared graduation, Kluckhohn recommended that he pursue a graduate career in anthropology at Cornell University.

Meanwhile, during his undergraduate years, the close friendship between Hughes and Jane Murphy had continued. Jane finished her degree in three and a half years and joined Hughes in Boston. The two were married during Hughes’s senior year at Harvard. After Hughes’s graduation, the couple moved to Ithaca, New York, where Hughes, following Kluckhohn’s advice, was accepted as a graduate student into the Department of Sociology and Anthropology at Cornell University. Kluckhohn had also suggested that Hughes seek out his colleague Alexander Hamilton Leighton as an advisor. Leighton and his wife, Dorothea Cross Leighton, had carried out research in New Mexico on psychosocial behavior among the Navajo together with Kluckhohn.5 Both Alexander and Dorothea were psychiatrists with a strong interest in culture and personality-based studies, and both considered a background in anthropology central to their work.

Shortly after their arrival at Cornell, Hughes and Murphy received funding to attend an applied anthropology meeting in Montreal, where Hughes was expected to introduce himself to Leighton. The resulting successful meeting with Leighton would turn out to be critical. Leighton was engaged in research in the Stirling County Study (SCS).6 The multidisciplinary study focused on physical and/or cultural environments and their impact on psychosocial behavior and related well-being. The SCS would have a major impact on Hughes’s future research. Among its various purposes, the study described some of its objectives or hoped for impacts as follows:

To penetrate and understand all aspects of life in Stirling County, to make observation both wide and deep and so miss nothing. Operations and achievement were, of course, a good deal more modest. Nevertheless it was possible to see, touch, and be touched by the patterns of living in the County in many different dimensions. Thus, not only have we conducted systematic surveys and key informant interviews and traveled repeatedly about Stirling in order to observe its characteristics and events, but members of our team have variously lived as neighbors,… We have been counselors and friends and we have also been counseled and befriended when this was sorely needed.7 (Hughes et al., 1960:7; emphasis mine)

The SCS began in 1948 in Halifax, Nova Scotia, under Leighton’s direction. Murphy became the director of the SCS in 1975. The SCS is one of the longest comparative psychosocial studies of mental wellness and illness ever conducted and was still active as of summer 2015. It generally includes wide-ranging sociological, psychiatric, and epidemiological data collection within specific territorial and socioculturally defined locations for comparative purposes.

Hughes began his graduate studies in 1951, just prior to Leighton’s return to Cornell. Once Leighton was back on campus, he became Hughes’s advisor. By 1952, Leighton had hired Hughes as his research assistant on the SCS. Leighton also hired Jane Murphy as administrative assistant to the SCS (Jane M. Murphy, personal communication, May 28, 2012). As Hughes wrote in his last departmental curriculum vitae, dated February 1997, “June 1952 through January 1953, Community study and survey research in Nova Scotia with Stirling County Study under the direction of Dr. Alexander Leighton and Dr. Robert N. Rapoport. Periodic field work in the country, 1953–59.”8

To grasp Hughes’s future contributions, some familiarity with the Stirling County Study and with the influence of Kluckhohn and the Leightons on Hughes’s work is helpful. One must also consider psychiatrist Adolf Meyer, whose work impacted the Leightons and thus also influenced Hughes. Jane Murphy, who worked side by side with Hughes in 1954–1955, was also an influence. The two collaborated even after divorcing in 1962 (Murphy and Hughes, 1965).9

Both Alexander and Dorothea Leighton were interested in what was called sentiment and values research. Each was a psychiatrist with a background in anthropology, having sat in on anthropology courses prior to meeting Kluckhohn in New Mexico in 1938. Leighton in particular was interested in work that reflected psychiatrist Adolf Meyer’s ideas and his case study approach to culturally informed psychiatric research.10 The Leightons were also interested in Kluckhohn’s concern with cultural boundaries and definitions. These complementary interests and objectives were apparent in their subsequent work among the Navajo in New Mexico with Kluckhohn in 1939, followed by research on St. Lawrence Island, Alaska, in 1940. Both studies were part of their psychiatrist-in-training period.

Upon the arrival of the Leightons in New Mexico, Kluckhohn introduced them to an accomplished Navajo translator and helped to arrange their living situation with a Navajo family. The Leightons eventually spent from January to May 1939 with the family who lived just south of Gallup, New Mexico. Each of the Leightons collaborated with Kluckhohn, publishing joint articles and manuscripts with him and with each other on their Navajo research; always their concern was psychosocial behavior and cultural context (see Leighton and Leighton, 1941, 1944, 1949; Kluckhohn and Leighton, 1946; Kluckhohn, 1949b; Leighton and Kluckhohn, 1947). According to Dorothea Leighton, the suggestion of St. Lawrence Island as a comparative research site had come from Arctic archaeologist Froelich Rainey, who recommended the site to Ralph Linton, the Leightons’ principal adviser while they attended classes at Columbia University on anthropological methods and theory (Leighton and Leighton, 1983:v).

The next year, in summer 1940, the Leightons spent 10 weeks on St. Lawrence Island (Figure 13.4), apparently using the same methodological approach and the same concern with sentiment and values and culture profiles employed in their Navajo work with Kluckhohn. The couple collected masses of cultural and behavioral data in order to examine how these were shaped by environmental conditions, cultural norms, institutional frameworks, and local social life.

Figure 13.4 Alexander Leighton and Dorothea Leighton with colleagues in Gambell, 1940. Left to right: Ted Cross, Alex Leighton, Dorothea Leighton, and Bill Field. Property of Dorothea Leighton, Johns Hopkins Hospital, Baltimore, MD. Dorothea Leighton Collection, UAF-1984-31-71, Alaska and Polar Regions Collections, University of Alaska Fairbanks.

Since the Leightons and Kluckhohn had become research partners and colleagues as early as 1939, it was no surprise that Kluckhohn advocated that Hughes become Leighton’s student. As noted, Hughes began graduate studies with Leighton in 1951 or 1952 and became Leighton’s research assistant on the SCS in 1952. He soon found himself conducting interviews in Nova Scotia that utilized the case history methods and survey techniques that Leighton had adapted from his time as a medical resident under Adolf Meyer at Johns Hopkins University. As SCS’s administrative assistant, Jane Murphy too became heavily involved in the study.

As Leighton’s research assistant and later his colleague, Hughes made extensive use of Adolf Meyer’s method, which involved culturally or environmentally informed analyses of human behavior and utilized case histories, often in the form of extensive life histories, to establish context for acceptable and deviant behaviors in different societies. This approach, along with Kluckhohn’s emphasis on culturally determined values, is apparent in much of Hughes’s writing. Hughes was particularly interested in Meyer’s insistence that a subject’s life history should be the starting point for psychological study. Leighton would go on to encourage Hughes to use Meyer’s suggested methods, which depended upon culturally or environmentally informed analyses of human behavior using case histories to establish context for acceptable and deviant behaviors in different societies.

The SCS, with its carefully defined key informant and case history–informed methodology, was designed to look for ways in which cultures under stress as a result of sociocultural change could be viewed in terms of their level of integration and/or disintegration. Integration was described as a sense of social well-being, belonging, or togetherness. Disintegration suggested that individuals exhibited a sense of isolation from others that generated a lack of community-level cohesion. According to the SCS research paradigm, this, in turn, would affect the overall mental and physical well-being both of individuals and the communities. How these levels were interpreted depended heavily on assessments of the degree of sociocultural shifts that a defined community had experienced and the degree of coherence, comfort, and community expressed by residents and/or that was apparent to a trained observer. This approach meshed well with Hughes’s previous study under Kluckhohn and with Kluckhohn’s emphasis on culturally determined values. The influences of Kluckhohn, the Leightons, and Meyer are all apparent in Hughes’s work and formed the bedrock of his later psychosocial research among the Sivuqaghmiit and among the Egba Yoruba in Nigeria that followed (Leighton et al., 1963).11 Indeed, the SCS methodology later dominated much of Hughes’s engagement in medical anthropology and his interest in the ways peoples cross-culturally discern and categorize mental illness, wellness, and depression and the possibilities those distinctions offer as a means of determining how to heal the afflicted.

At some point, Hughes must have realized that he had joined or perhaps found himself woven into a family of psychosocial and anthropological research traditions. The traditions included values orientation theory as these related to “the notion of pattern, configurations and culture profile” proposed by Kluckhohn (Hughes, 1953:6–7); the measures of behavior and depression associated with Leighton’s SCS; and the use of case history methodologies as envisioned by psychiatrist Adolf Meyer. Hughes’s M.A. and Ph.D. research also relied on both Leightons’ earlier St. Lawrence Island studies from 1940 and his reliance upon and early collaboration with Jane Murphy.

By 1952, the Leightons together had convinced Hughes to use their field notes from their 1940 research on St. Lawrence Island for his master’s thesis. As already noted, in 1939, the Leightons had received funding to conduct culturally based psychosocial research not only among the Navajo but also among the Yupik of St. Lawrence Island. Relevant here is that the couple had recorded numerous life histories in Gambell, one of the island’s two villages, along with masses of cultural information about religious practices and subsistence lifeways in order to examine how these were shaped by environmental conditions, cultural norms, institutional frameworks, and local social conditions. Various components of the Leightons’ St. Lawrence Island research were eventually deposited in the Alaska and Polar Regions Collections at the University of Alaska Fairbanks in the Dorothea C. Leighton Collection, 1904–1965; a selection from the collection, representing about a third of the notes and interviews, was published 43 years after their initial research (Leighton and Leighton, 1983). However, long before that, Hughes had agreed to work with the Leightons’ field notes as his master’s project. He took on the onerous task of organizing, arranging, and explicating the Leightons’ notes and transformed them into a viable historical and cultural resource on Sivuqaghmiit life in 1940.

By June 1953, Hughes had worked his way through the Leightons’ research files and completed his master’s thesis, “A Preliminary Ethnography of the Eskimo of St. Lawrence Island, Alaska.” His stated objective for his MA thesis was to

systematize the body of field data which was collected by the Leightons [in order] both to present as coherent and full account as possible of the culture in the summer of 1940, and also in order that the data may serve as a baseline against which culture change may be plotted, the author [Hughes] plans to follow up … with a period of field study of the same Eskimo group which will be focused on culture change; and such a later study will best achieve. (Hughes, 1953:3)

At the beginning of chapter one, Hughes outlines how he approached the writing of his thesis, a task that reveals much about how he envisions research that has the potential to illuminate sentiments, values, and what he intimates are covert and overt patterns of cultural behaviors as described by Kluckhohn. He describes his broad intent, following Kluckhohn’s notion of patterns and configurations of cultural constructs, in this way, quoting Kluckhohn:

“The overt culture is the content or the concrete aspects of a culture; the covert culture refers to the structuring of that content, of which … there is minimal articulate awareness on the part of the culture carriers.” To structural regularities in this covert culture Kluckhohn applies the term “configuration” … Finally, he says that “A pattern is a generalization of behavior or of ideals for behavior. A configuration is a generalization from behavior.”

The distinction between the “overt” and the “covert” culture will generally be followed here, and the term “pattern” will be defined as a “structural regularity in the overt culture.” While the major emphasis in the thesis is on the systematizing of patterns, there will be explorations into the area of integrative principles in the cultural structure; i.e., some consideration will be given to the area of “configurations,” or “themes,” or “values.” There will be then four dimensions of each pattern category: 1.) the “behavioral” and the 2.) “ideal” regularities; 3.) the older aboriginal forms as they existed before being appreciably altered by persistent contact with Americans, and 4.) these forms as they were functioning in the summer of 1940.

Whenever possible the attempt will be made to relate the gross behavioral pattern to such elements of the more subtle culture as the sentiment and belief systems involved and to value patterns (Hughes, 1953:67).

Hughes’s description brings to mind Clifford Geertz’s often-quoted passage on culture patterns: “culture patterns have an intrinsic double aspect; they give meaning, that is objective conceptual form to social and psychological reality both by shaping themselves to it and by shaping it to themselves” (Geertz, 1973:93).

Overall, Hughes’s 1953 master’s thesis not only sets the stage for the future field site location of his doctoral research but also informs the reader of his view of culture constructs as well as his approach to psychosocial research. His interest in cultural structures would go on to inform his Ph.D. study. It anticipated Hughes’s preoccupation with values and the characterization of disintegrative psychosocial behavioral changes when cultures experience major transformations away from a so-called indigenous cultural system or traditional form to one that is characterized in terms of its adaptation to “outsider” changes.

The 1953 master’s thesis is also a window into Hughes’s skills at organizing data. When viewed in retrospect, his master’s thesis revealed no startling social scientific breakthroughs but documented, via a descriptive narrative, the pre–World War II lifeways and practices of the Yupik people of Gambell. As Hughes had intended, lifeways and practices would later become the baseline for his Ph.D. comparison with the Gambell people’s life as he encountered it in 1954–1955. At the same time, the thesis itself is a highly readable storehouse of information about Sivuqaghmiit culture before the people had incorporated many contemporary fixtures into their lives, such as electricity and reliance on imported foods and fuel. Hughes himself would come to see the community of 1940 as one that demonstrated a comfortable degree of integration in contrast with the Sivuqaghmiit world that he encountered in 1954. One obvious conclusion one can make after reading through the thesis is that Hughes seems to have had a fine organizational mind. Indeed, Ronald Simons, Hughes’s colleague at Michigan State University in the late 1960s and 1970s, commented upon Hughes’s extensive organizational gifts (Simons, pers. comm., 2013).12

Once Hughes completed his master’s thesis in conjunction with the Stirling County Study and incorporated the cultural comparisons component into his Ph.D. research design, he embarked on his preparations for his Ph.D. research on St. Lawrence Island. In the interim, he spent about eight months engaged in field research for the SCS in Nova Scotia. This latter allowed him to extend his field experience utilizing the Meyer method to build the SCS database, a process that surely prepared him for his research in Gambell. The SCS design involved detailed data collection in two locations, each having different historical, social, ethnic, and economic backgrounds. The intent was to identify their already mentioned integrative and disintegrative features along with data collection. Conclusions of that first round of research suggested that mental well-being was, indeed, affected by the degree of disintegration as identified through the study.

Hughes’s objective for his research on St. Lawrence Island would be to document social change as experienced by the Sivuqaghmiit and to use the same lens and methods employed in the SCS. His specific focus was twofold. First, the study would determine how exposure to the outside world might be instrumental in turning the population away from their traditional homeland and toward white culture as exemplified by the Alaskan mainland and a series of outsider visitors to the island. Second, it would assess the resulting degree of disintegration as the community members in varying ways attempted to maintain some balance between their satisfaction with their traditional lifeway and their attempts to adopt or embrace elements of a different lifeway. Hughes ended his master’s thesis with a quote that suggested the degree to which the Leightons’ collected life histories on St. Lawrence Island life had affected his view:

In a cold world of huge, moving chunks of ice whipped by extremely high winds, a world in which the elements of nature seem to combine overwhelmingly against human desire and in which even the animal forms must be killed and their flesh consumed in order that men may live, the hazards of his life and the imminence of death hover about the Eskimo from his earliest days. Death from hunting accidents, from drifting away on the ice, from drowning in a storm, from being lost in a blizzard, and—most of all—from sickness are recurrent, plangent themes of the life stories. There is no one who has not lost numbers of either siblings, childhood friends, parents, spouse, or children through some form of sudden, unexpected death. (Hughes, 1953:213)

When Charles Hughes arrived on St. Lawrence Island in 1954, he found entry into the world of the Sivuqaghmiit quite moving and somewhat disturbing. The “Torn Grass,” the opening chapter for his Eskimo Village in the Modern World (Hughes, 1960), gives some sense of what he was feeling on that first day in June 1954. As he and Jane left the ship that had carried them to the island, they found themselves among a small group of returning outsiders, a teacher, a nurse, and some non-Native Army personnel. The village was on hand to greet members of the National Guard returning to the village after having been out on training. The Hugheses were greeted by no one. As they walked into the village, Hughes was keenly and painfully aware of the bare gravel, a surface once covered with high grasses, which had been destroyed in the aftermath of the Army’s attempt to use the village shoreline for its defensive efforts. The Army had been an established presence since 1948. Everywhere there was the sight of twisted metal carpeting, leftovers from a futile attempt by the Army to create a viable landing surface. Even in 1987, when I first walked the beaches of Gambell, the metal grating mentioned by Hughes was still very much in evidence, its sharp, rusty edges a caution for those driving snow machines and all-terrain vehicles. When the Hugheses landed in 1954, the Cold War was in full swing, and the Iron Curtain had descended along the Russian-American border only six years prior. Gambell, perched on a gravel spit close to the Northwest Cape on St. Lawrence Island, was only 38 miles (61.2 kilometers) from what was then the Soviet Union.

For the first few months after arriving in Gambell, the Hugheses engaged mainly in situating themselves in the community. Their living situation was in the middle of what is now known as the “old village” along the west beach. Their dwelling was an empty summerhouse (Figure 13.5) belonging to Vernon and Beda Slwooko (Figure 13.6), and their presence in the middle of the village meant that they soon became a village fixture. During the 15-month period (June 1954 to September 1955), whenever Charles and Jane were at home, the children of the Slwookos, their host family, were in and out of their house, offering a more intimate view of Gambell life than they could have had in any other way. Because their house was next door to the Slwookos’ home, they offered built-in entertainment for the children (Murphy, pers. comm., 2012). From the more than 1,300 photographs that Hughes took during the field year, however, he chose only a few that had been taken inside the house to include in his publications. Several were camp shots, taken inside hunting cabins scattered along the island, often in areas where an extended family once had more permanent residence. One picture that stands out is of the young, red-headed Charles with Richard Oktokiyok, a consultant with whom he spent many hours (Figure 13.7). It provides a brief view of the delight that Charles obviously felt as he engaged in interviews with an Elder.

Figure 13.5 Jane Murphy inside their residence in Gambell, 1954. Photo by Charles Hughes; courtesy Leslie Hughes.

The Hugheses at first were just one more pair of outsider whites to arrive in the village and live in the village for a short while. They had been preceded by white school teachers and missionaries in the 1890s, by explorers and whale hunters even earlier, and by a mix of military, archaeologists, and peripatetic medical personnel, to name but a few. However, the Hugheses were the first cultural anthropologists to set up housekeeping and live in the village for a lengthy stretch of time, and they soon became a familiar presence in the village. Once the Hugheses had achieved a degree of acceptance, the two set about creating a database that they planned to compare to the 1940 baseline data. Central to the data collection was a series of key informant interviews modeled after Meyer’s approach.13 Hughes and Murphy engaged throughout the year in participant observations as they carried out the daily chores and participated in community events common to routine village life.

Figure 13.6 Vernon and Beda Slwooko, 1954. Photo by Charles Hughes; courtesy Leslie Hughes.

Establishing a second database for the 1954–1955 period, required for the comparison with the Leightons’ 1940 data, laid the groundwork for Hughes’s focus on two areas. One was psychosocial shifts in attitudes generated by increased contact and familiarity with the mainland white world because of the massive U.S. military presence in its facility located just beyond the village and the conflicts generated around that presence. The second was the status of people’s physical and mental health, particularly the perceived threat to physical wellness. Numerous threats to people’s wellness stemmed from living in an isolated community with little access to health care. These threats included health-related traumas, including seizures, heart attacks, injuries, exposure to diseases, and other life-threatening situations. Also, events such as unpredictable shortages of available food resources were associated with dependence upon the local hunting economy and the emotional trauma associated with life in a community with a high rate of infant and general mortality.

Figure 13.7 Charles Hughes with Richard Oktokiyok in Gambell. Photo courtesy Leslie Hughes.

Data collection in each case involved interviews with large numbers of people. The Hugheses together interviewed 26 individuals, and by the end of the Hugheses’ stay in Gambell, the two were regularly completing four interviews per day. Their interviews in this pre-recorder era involved carrying a typewriter to the consultant’s home and typing the interview simultaneously as the consultant spoke. Hughes adds that the focus was on 16 of these consultants (Hughes, 1960:24–25). Along with the life history and psychosocial change questions, the Hugheses collected data on community health, represented in Charles Hughes’s dissertation and later in An Eskimo Village in the Modern World (Hughes, 1960) by 24 tables on birth, fertility, cause of death, mortality and its relationship to clan (ramket) membership; on various types of hunting productivity; and on types of and changes in food consumption, including food diaries kept by select individuals, and the degree of cleanliness in households. They also carried out separate, more focused interviews with select individuals and administered nine Rorschach tests. Altogether, the Hugheses’ research in the village includes 33 tables, 12 figures or charts, and 13 plates containing village photographs. Along with his many photos, Hughes also filmed a short sequence of the results of a day of hunting unloaded on the beach. Both Charles and Jane Hughes kept detailed descriptions of their daily activities in combined personal diaries in addition to Charles Hughes’s formal research notes.

Hughes moved back and forth between his emerging database for 1954–1955 and the Leightons’ 1940 baseline as he explored psychosocial behavioral shifts. Always his purpose was to determine the degree of ongoing integration into, or psychosocial leaning away from, traditional Eskimo ways and toward white cultural ways as evidenced by the interactions between Gambell residents and the soldiers living in their camp at the base of Sivuqaq Mountain. In the same vein, he also questioned residents about their sentiments regarding Civil Aeronautics Administration personnel and their families, who had occupied three specially built homes on the west beach for almost a decade while they administered a new weather station established there. In several lengthy chapters in his book that followed completion of his dissertation (Hughes, 1960), Hughes quoted numerous individual responses that suggest shifting attitudes toward the white world culture each of these non-Native groups represented.14

Although most chapters in An Eskimo Village in the Modern World (Hughes, 1960) contain villager responses used as evidence of psychosocial shift toward the outsider culture, two stand out: “Warmth and Well-Being” and “The Texture of Social Life.” Even taking into consideration mixed feelings about the effect of the Army presence, with its alcohol, parties, and interest in temporary female company, many of the responses suggest a strong preference for white culture.15 The presence of the Army during Hughes’s stay allowed him to observe people’s response to an overwhelming number of non-Natives brought to the island because of the Cold War.16 The islanders had never encountered so many representatives of any non-Native culture living among them before, and to date, they have not experienced it since. The Army camp was less than a mile beyond the village itself, near the “mountain,” a 600-foot (183-meter) high bluff that defines the end of the village.17 At the time the Hugheses were on the island, the local population of Gambell was approximately 300, excluding the local Army presence. It seems likely that the Army encampment must have housed up to 100 or more people, all male and all non-Native.

In general, the information-gathering process, especially the interviews, was divided between Hughes and Murphy. Hughes mainly interviewed the men, and Murphy mainly interviewed the women. The objective was to learn about the lives of each sex in order to learn firsthand the degree to which each group was experiencing psychosocial shifts. Charles often accompanied men on hunting trips to gain a greater understanding of men’s lives. His interviews were directed toward behavioral and attitudinal shifts in a number of areas, and his observations often focused on what men in the village did for a living. In addition, he was interested in the activities of the Village Council, the village store, the nurse’s station, and the church and in the comments his informants made about the Army base, which represented white culture. (Hereafter informants are referred to as consultants except when specifically referred to as “key informants” as used by Hughes.) He also explored kinship relations and clan or ramka interactions.18

Figure 13.8 Richard Oktokiyok with his granddaughter Beulah. Photo by Charles Hughes; courtesy Leslie Hughes.

Each subject added to the baseline contributed to a multidimensional view of the village’s lifeways as caught in a psychosocial behavioral shift. The interview process required translators and Hughes worked with several, in contrast to Murphy, who relied heavily on one woman. Hughes did hunt often with a particular family, the Silooks. In conjunction with his interest in the development of the village council, he often spoke with James Aningayou (1877–1959), an Elder known in the village as the first “true Christian,” about the council in its early years. For the most part, though, Hughes did not form firm friendships with his consultants with the possible exception of Richard Oktokiyok (1879 to ca. 1960), a well-known shaman or village aliginallghi, who had given up his practices because he felt they would hurt his granddaughter Beulah (Figure 13.8).19 Hughes also formed a friendship with Leonard Nowpakahok, a young man who was to marry Beulah.

The second round of research dealt specifically with health and wellness issues and relied heavily on the work of Jane Murphy and her key informant. Murphy was responsible for reconstructing birth, death, and mortality figures for the 15 years following 1940, documenting individual experiences of sickness, both physical and mental, and recording causes of death. Murphy worked closely with Beda Avalak Slwooko (Figure 13.9), who would later be referred to in publications as the key informant.20 Jane Murphy and Beda Slwooko, who was also the Hugheses’ landlady, worked together very well. Under Murphy’s direction data collection of birth, death, and disease figures took place, but it depended substantially on Beda’s remarkable memory. In reference to it, Hughes notes only that “in order to get as systematic health data as possible for studying the effects of morbidity, a key informant was interviewed about salient health experiences of everyone in the village, using the 1940 census as a base” (Hughes, 1957, pt.1:172).

Figure 13.9 Beda Slwooko cutting up a seal with a traditional woman’s knife, 1955. Photo by Charles Hughes; courtesy Leslie Hughes.

Beda Slwooko and Murphy, working together, also administered a Health Opinion Survey, referred to by them all as the HOS. It dealt with contemporary community sentiments about health and wellness. Beda Slwooko served as a translator during interviews with those who participated in the HOS and for much of the related data collection. Using the HOS, the two women compiled tallies of sentiments concerning general health and wellness, high incidences of infant mortality, and feelings about overall experiences of disease, sickness, physical trauma, accident, injury, and death in the population in 1954–1955. In addition to being the key informant, Beda also served as a consultant, recording her own life history and providing additional information about causes of death for a previous generation.21 For the health and wellness data, Murphy’s work included both administering the health survey and related health data collection and accompanying quantitative analyses. She was responsible for recording women’s life histories, a task made easier because Beda served as her translator during the interviews. Jane Murphy and Beda Slwooko eventually developed a strong personal friendship, and Beda’s life story would later appear in Jane’s dissertation.22

As with all field research, the personality of the researcher shapes the relationship between researcher and consultants. In that respect, it should be noted that Hughes was under pressure in 1954–1955 because much of the time he was on the island the Army attempted to send him to Korea as a member of the U.S. Army Reserve. Although the Korean War had ended in 1953, the United States maintained a military presence there, and Hughes was subject to the draft. In Murphy’s words, there were “many telegrams back and forth” at the time and “members of the Department of Sociology and Anthropology at Cornell acted on his behalf in an attempt to have the draft request nullified.” Yet for a while it looked as if Hughes would have to leave and Murphy would stay on to “finish things up” in his absence, following methods familiar to them both based on the SCS (Murphy, pers. comm., 2012). One consequence was that for months Hughes’s mind was in at least two places, worrying that he would be sent to Korea in the midst of his research. Had he left, the consultants would have had to adjust to a second researcher-consultant relationship since Hughes and Murphy differed in their approaches. Hughes, perhaps even then (at 26 years old), must have had some of the formal characteristics that led his colleague Ronald Simons to describe him many years later as unique, a man devoted to his Scottish heritage. In Simons’s recollection Hughes had a formal quality to his speech and interaction, “expressed through a great gravitas … he was always kind or thoughtful and … with this kind of pompous style” (Simons, pers. comm., 2013).

Drawing on my own experience in Gambell in the 1980s and 1990s, it seems that for Hughes to have collected the massive amount of data, to interview so many individuals, and, indeed, to have his many consultant contacts over the course of his 15-month stay in the village, he would have to have been a man who did not enter the village with some type of idée fixe, some ponderous theoretical position that he was bent on proving. Instead, he seems to have set about to look for sentiments and values as he saw them being acted out or discussed soberly in response to his serious questions. Hughes’s contacts in the community were primarily with men of his own age or older. In general, Hughes’s approach to people may have been both quiet and possibly evincing the gravitas that Simons mentions. Thus, his interviewer-consultant relationships would have been colored by his way of approaching people: reserved, respectful, methodical, and as a conscientious recorder of details. I believe this would have impressed his various key informants because Yupik people are, at the very least, pragmatic problem solvers. They are also careful observers and keep keen mental files of what they have observed and heard, even now, with the intervening effect of widespread media. Charles himself was objective and much engaged in meticulous organization of his observations and his data. His presentation of self would have been appreciated. I believe that Charles would have agreed with Leighton and Murphy that

“culture” is a precipitate of the group’s history and expresses its adaptation to the physical environment. It is characterized especially by what A. I. Hallowell has called a “psychological reality.” That is, it refers to the shared patterns of belief, feeling, and knowledge—the basic values, axioms, and assumptions—that members of the group carry in their minds as guides for conduct and the definition of reality. (Murphy and Leighton, 1965:15; see also Leighton and Hughes, 1961; Murphy, 1964)

This acceptance of the world in process and its inevitable tie to individual perception would also have made participant observation an effective research method in Gambell.

Toward the end of 1955, Hughes felt that his data showed an irreversible drift away from the traditional Yupik culture of 1940 (Figure 13.10) and toward a psychosocial behavioral shift in identity toward a white model. In other words, he saw a society moving away from integration and most likely parting ways through the process of disintegration. He believed that the traditional ways were fast disappearing, overwhelmed by the white cultural model and a growing tendency to identify with a desirable white lifeway rather than with the traditional Eskimo way. At the end of the last chapter in An Eskimo Village in the Modern World, “The Broken Tribe,” he concludes with this statement:

Figure 13.10 Tug of war, Fourth of July celebration in Gambell, 1955. Photo by Charles Hughes; courtesy Leslie Hughes.

The story of Gambell, a modern descendant of the ancient Eskimo village of Sivokak [sic], is apparently another instance of a small community which from 1950 through the middle years of the 1950’s has been irrevocably swept up in the world-wide transition from a subsistence economy and ethnocentric moral order to a closer relationship with the pervasive industrialized economy of the modern world and the abstract moral order which seems to be a feature of that world. Whether the people whose current patterns of interaction and interdependence comprise Gambell as a social unit can successfully adapt their personal lives and habits to the new conditions imposed by the mainland is one question. Whether Gambell as sociocultural system in its own right will continue to survive and function with anything resembling an integrative, cohesive, and relatively perduring community is quite another matter. The unique contribution which, through several thousand years, the Sivokakmeit [sic] have made to the infinite variety of man’s cultures will soon, in all probability, pass from practice to the written page (Hughes, 1960:391–392).

Once Hughes finished his Ph.D. in 1957, he followed with the publication of his ethnographic study of the Sivuqaghmiit in a book, An Eskimo Village in the Modern World (Hughes, 1960). It would turn out that Hughes was actually the first person to conduct a long-term study of an Alaskan Eskimo community, and his book was, in fact, the first ethnography of a contemporary Alaskan Arctic community.23 Its focus was cultural change and its impact on the lives and emotional and psychological environment of the community in Gambell and was based on his yearlong residence. Most of the text is drawn closely from his doctoral thesis. It was well received among Arctic scholars and remains an important reference on St. Lawrence Island Yupik culture, kinship structure, and spiritual traditions (McFeat, 1960). It also provides a significant record of the transformative effects of high infant mortality, sickness, and poor community health. It offers, too, a detailed account of the psychosocial change process and its disintegrative effects as a result of increased contact with a changing and modernizing world.

In the words of James VanStone, one of the book’s reviewers (whose work in the Alaskan Eskimo community of Point Hope would follow shortly after Hughes),

The study of culture change through the descriptive analysis of small communities, a methodological approach which has characterized anthropological research during the last two decades, has only recently been used in the arctic area. Several community studies have been carried out in Alaska during the last five years and this excellent study of the village of Gambell (Sivokak) on St. Lawrence Island is the first to appear in print. In fact, it is the first study of an Alaskan community to be published since Robert Marshall’s Arctic Village in 1933.… Dr. Hughes’s monograph would be an important contribution if it were simply a descriptive account of a modern Eskimo community. However, it is a great deal more than that. His analysis of culture change is placed within an exacting conceptual framework that will have wide application for future arctic studies. The book is interestingly written with the author’s extensive use of quotations from informants serving to heighten the dramatic qualities that are inherent in the data. There will be other Alaskan community studies, but this monograph sets a high standard that will be difficult to equal. (VanStone, 1961:159–161)

Upon his return to Cornell, Hughes was offered a research associate position on the SCS and once again was heavily involved in the Stirling County Study’s primary field site in Nova Scotia. While still with the SCS, he traveled to Africa and carried out comparative research among the Egba Yoruba of Nigeria for five months (Leighton et al., 1963).24 His interest in cross-cultural comparisons of psychosocial behavior and his engagement in the SCS eventually led to a position at Michigan State University (MSU), where he was appointed director of the African Studies Center. Once at MSU, he became deeply involved in the emerging field of medical anthropology. According to Simons, MSU was

really quite a pioneer in medical anthropology and so pretty soon on, there formed a strong linkage between people who had done work in various places, whose general interests were in medical/anthropological kinds of questions. And Charles was very active in that group. I wouldn’t say that he was a leading light, because they were all pretty high powered people. And we would meet and we developed a curriculum in medical anthropology. At that time, I knew of his previous life, and it was very much his previous life.… Charles did have Nova Scotia in his heart. And he had a place there, and he did, on rare occasions, go back. (Simons, pers. comm., 2013)

One of the interests Simons and Hughes shared was the concept of culture-bound syndromes. The two published a coedited volume on the subject (Simons and Hughes, 1985), and according to Simons, Hughes’s perspective was more psychiatric and his own was more anthropological, a bit of a surprise since Simons is a psychiatrist (Simons, pers. comm., 2013). Hughes remained at MSU for 11 years (1962–1973).

Hughes left Michigan State in 1973 to take a position at the University of Utah. He joined the Department of Family and Preventive Medicine (formerly Family and Community Medicine), School of Medicine, where he served as chairman and as director of graduate studies from 1973 to 1978, director of the master of science in public health program from 1979 on, and master of public health programs from 1989 on. He served as president of the Society for Applied Anthropology (1969–1970) and as associate editor for Qualitative Health Research and the Journal of Psychoanalytic Anthropology. He would become instrumental in forming the Society for Medical Anthropology, a major section in the American Anthropological Association, together with his longtime colleague Dorothea Cross Leighton. He served as its president in 1981–1982. Hughes was well known in his field, and these accomplishments are but a fraction of a long list of prestigious appointments, public service consultancies, publications, and other achievements.

The experience on St. Lawrence Island moved into the background of his research, perhaps for personal reasons, and remained there for much of Hughes’s career.25 Nevertheless, his publications reflect his experiences there, even though he no longer continued his research focus on the island. After 1955, he would visit Gambell only twice; the first time was in February 1979 in conjunction with a trial held in Nome, Alaska, where he appeared as an expert witness in cultural anthropology in a case involving the “wrongful death of Eskimo clients in an airplane crash on St. Lawrence Island” (Hughes, 1997:14). The second time was in 1994, when the Gambell community invited him to a workshop where he was asked to discuss “the role of elders in traditional Yupik society” (Hughes, 1997:14).

From 1955 on, however, Hughes was responsible for numerous publications. He drew on his SCS experience and his St. Lawrence Island research as well as his engagement in psychosocial research in Africa and elsewhere and the role of life histories in cross-cultural psychiatry and anthropology. Of his post-1955 publications, several of the early articles were of particular interest. These included his analysis of Yupik kinship (Hughes, 1958b), his coauthored article with Alexander Leighton on Eskimo suicide (Leighton and Hughes, 1955), and his lengthy comparative article on change among Eskimo peoples in Alaska, Greenland, Canada, and Russia (Hughes, 1965b). In addition, Hughes also translated several Russian articles on the northeastern Arctic, including I. K. Voblov’s “Eskimo Ceremonies” (Voblov, 1959) and Leo Fainberg’s discussion of Eskimo kinship systems (Fainberg, 1967). Hughes also authored two significant chapters in Murphy and Leighton’s coedited volume, Approaches to Cross-Cultural Psychiatry (Hughes, 1965a; Murphy and Hughes, 1965), to which I will return. Hughes’s four chapters in the Arctic volume of the Smithsonian’s Handbook of North American Indians (Hughes, 1984a, 1984b, 1984c, 1984d), written in the 1970s, are perhaps most well known. They drew on both his master’s thesis and his research for his dissertation in 1954–1955 and beyond.26

Of particular note is Eskimo Boyhood: An Autobiography in Psychosocial Perspective (Hughes, 1974), a detailed and compelling autobiography that recounts the life of a St. Lawrence Island Yupik boy during his preadolescence and early adolescent years. The author, Leonard Nowpakahok (Figure 13.11), who had been taking piano lessons from Jane Murphy, showed it to Hughes during their 1954–1955 stay in Gambell. He was only a few years younger than Hughes himself, and as noted, he was associated with the family of former shaman Richard Oktokiyok. As Hughes explained, the author was in his early twenties when he wrote his story. Leonard appears in the book under the pseudonym Nathan Kakianak, penned by Hughes. Although I am not familiar with the details of Hughes’s decision to publish Nowpakahok’s autobiography, it is fairly well established that Margaret Lantis, known for her work with the Yupik people on Nunivak Island, Alaska, had encouraged Hughes to publish it and wrote a positive review after it appeared. Much of Eskimo Boyhood was actually written in the years just after Leonard Nowpakahok had left the island, sometime in 1955, to receive treatment for tuberculosis. Hughes enthusiastically encouraged Leonard to continue with the autobiography, only the beginnings of which had Leonard shown to him. The writing had been started originally upon a suggestion from the local schoolteacher as a way to continue his education (Leonard had only completed fourth grade). Hughes also asked Leonard to keep a daily diary for him while he was in the hospital. Hughes quoted a selection from the diary in his first book (Hughes, 1960:94–95). In reference to Eskimo Boyhood, Hughes says, “the document … is actually an autobiography of more than 200 full-size pages written under financial contract [with Hughes] over a period of several years” (Hughes, 1965a:295). Eventually, Hughes lightly edited the volume prior to publication. As Hughes notes in his introduction,

Figure 13.11 Leonard Nowpakahok, 1931–1988. Photo by Charles Hughes; courtesy Leslie Hughes.

The purpose of this book is to portray the first steps taken into that life by a young Eskimo, Nathan Kakianak, who lived it and who here recounts it. With only slight editorial changes … the life story was written (in English) at my request and mostly under conditions conducive to recalling nostalgic personal memories, for much of the first part was set down while he was hospitalized with an advanced case of tuberculosis.27 The autobiography is presented almost in its entirety; only a few sections have been deleted to shorten the document and minor editorial revision and grammatical alterations made for easier reading. (Hughes, 1974:3–4)

Eskimo Boyhood, which stands alone in its quiet, simple, and elegant recounting of a boy’s growing up in Sivuqaq, is Leonard Nowpakahok’s articulate account of his youth, an extraordinary description of how the Yupik kinship system works with its emphasis on respect for Elders and its methods for teaching male and female roles. Leonard’s description offers the details of his interactions with family, peers, and outsiders, through which he absorbed both the system and the knowledge needed to survive in his community. A review by Margaret Lantis, Hughes’s colleague and another pioneer in the Eskimo biography field, states that

Eskimos (both Inuit and Yuit) have a high reputation as socializers of their children. This life story and its analysis suggest why — actually how Eskimos handle effectively the growing-up process. The autobiography is, therefore, worth our reading, even though it at first appears long (about 350 pages) and detailed for an account covering only ten years of a boy’s life. One is reminded that the years of approximately five to fifteen, when a boy moves progressively farther out from the family, are busy years of learning. The style of their telling is straightforward, the type is large, and the book altogether easy to read. The line drawings are appropriately childlike. To assure anonymity of the subject, there are no photographs. The young man called “Nathan” was encouraged by Hughes to write much of this account while he was hospitalized for tuberculosis, a common experience among Alaskan Eskimos twenty years ago, and Nathan entrusted his life story to Hughes, an anthropologist now at the University of Utah, for publication.… We can be grateful to both for their frankness and effort. (Lantis, 1975:161–163)

In Eskimo Boyhood, Leonard Nowpakahok’s story begins with Charles Hughes’s introduction in which he details Yupik life through a psychosocial lens as Hughes observed it in the 1950s, together with a standard background history of the community. He follows Leonard’s story with a section called “Self and Society” that offers an analysis of the life that Leonard has just described in terms of psychosocial behaviors and roles that emerge and are solidified in the course of a young man’s training and upbringing by his family. Although I have some questions regarding one part of Hughes’s analysis, his focus on the Oedipal transition, which alludes to possible hidden hostilities that accompany father-son relationships, most of the analysis deals with three selected roles and Leonard’s dealing with them as a young adolescent. Hughes also analyzed Leonard’s autobiography in psychosocial terms earlier (Hughes, 1965a:285–328), in a chapter in Approaches to Cross Cultural Psychiatry (Murphy and Leighton, 1965). Hughes used a combination of event sequences coupled with role analysis and role learning and selected examples drawn from Leonard’s story to analyze this portion of his life history. It was a careful exploration of the use of life history as it affects personality formation and the development of social values. This earlier analysis is quite powerful, and the two should really be read together.

At the end of An Eskimo Village in the Modern World (1960), Hughes lamented the loss of traditional Sivuqaq culture, and to some degree Leonard Nowpakahok came to epitomize for Charles Hughes what must happen when those brought up during times of massive change must endure the consequences. Apparently, for Hughes it seemed that the community would have to succumb to white culture with little ability to make an informed choice or to exercise control over the outside forces that challenged young men like Leonard and others like him. It is clear from Hughes’s ending paragraphs in Eskimo Boyhood (1974), in his earlier remarks in An Eskimo Village in the Modern World (1960), and at the end of his Ph.D. dissertation that Hughes envisioned the future for Gambell as the ending of traditional values and the impending tragedy of that psychosocial shift away from Yupik culture that had so long been represented by the Sivuqaghmiit. Years later, in an article on indigenous community survival, Marshall Sahlins focused especially on Hughes’s account of life in Gambell. It is worth reading what he had to say and to consider some of the changes in Hughes’s thinking following his return visits to Gambell in 1979 and 1994. According to Sahlins (1999:vii),

A sense of impending doom attended the concluding chapter of Charles Hughes’s ethnography of Gambell Village on St. Lawrence Island in the Bering Sea,… “Indeed the time has passed,” Hughes said, “when entire groups or communities of Eskimo can successfully relate to the mainland economy and social structure” (1960:389). For Hughes, two movements in opposite directions—of mainland Western culture to the island, and of islanders to the mainland—were between them tearing the indigenous society to pieces. The Gambell villagers who moved to the mainland were “no longer Eskimos” Hughes believed, “no longer people who retain a cultural tradition of their own.” In the 1950s and 1960s, when young men went off to the US military or to mainland schools under the sponsorship of the missions or the Bureau of Indian Affairs, when the BIA shipped whole families to Anchorage, Seattle, or Oakland under Relocation and Employment Assistance programs, the understanding was they would learn to live like white folks of the species Homo economicus, sever their relations to their villages and their cultures—and never go back. “They perforce have to forsake the overarching structure of Eskimo belief and practice,” said Hughes.… “In effect, if they are to adjust to the white world they must become as much like white men as possible. And the more that people move in that direction the more Gambell, as an Eskimo village, disappears from the human scene” (1960:389).

Hughes never wrote about what Gambell was like when he visited it in 1979 and 1994, leaving the impression through his earlier work that there was no hope for the people of Gambell to enter the modern world without becoming a gathering of lost souls, having given up the traditional values and elements of a lifeway that he had come to appreciate back in the 1950s. Yet as a result of his two later returns and his engagement with St. Lawrence Island long distance when I was living in Gambell in 1987–1988 and off and on in the years leading up to his death in 1997, Hughes’s sense of the possible survival of a Gambell Yupik society, shaped by the Eskimo values and way of life he had so appreciated, seemed to emerge. This renewed sense of hope probably took hold first in February 1979. It was then that Hughes traveled to Gambell in his role as an expert witness after the crash of a Wien Airline plane. Many years later, Hughes wrote to me in Gambell with the following request:

Please give my warm regards to Leonard Nowpakahok, will you. I still remember my pleasure—about nine years ago now—when I spent several hours in his house interviewing him about the Wien airplane crash and its effects on the village. It was so nice to see him with a house full of children; as he proudly said, he now had his own (hunting) crew! (Charles Hughes, personal communication, December 1, 1987)

Later, on July 17, 1988, Hughes wrote to me:

Your reflections on return to the kind of life and environment that had been most familiar bring back my own. Not only the food, and the fact that it had been cooked by somebody else, but just the joy of walking on something other than slipping gravel under my feet!… Incidentally, I was sent a sheaf of newspaper clippings that covered the 22 day ordeal of the Slwookos on the Bering Sea ice. That also, brought me back to some poignant memories—including the one time that I fell into the Bering Sea ice in January and we were locked in the ice drifting off to Siberia.28

If we turn to Leonard Nowpakahok’s experience, both away from the island and his return, there is yet more confirmation of that reason for hope. Leonard traveled to the mainland and learned a great deal in his young-adult years. He then returned to Gambell and became a much-respected member of the community. His values remained anchored in the traditions of his father and uncles, although he spent several years undergoing training and working away from the community. He became a hunter and a teacher’s aide in the high school, known to everyone as Mr. Leonard. In 1987, during my first year in Gambell, Leonard, who was 57 years old, was diagnosed with cancer. When he could no longer move about, he gathered his three sons near his bedside, and for two months, he passed on his hunting knowledge and other traditional ways to them. When Leonard died in April 1988, his funeral was attended by relatives and friends from around the Bering Strait region, who arrived by air from the mainland and by snow machine from the neighboring village of Savoonga to say goodbye. The funeral service was long and filled with departure hymns that were sung partly to postpone the inevitable moment when his body would be taken by sled to the top of Sivuqaq Mountain to join others who already lay there. His wife, Amaghalek (Beulah), the granddaughter of Hughes’s friend, the former shaman Richard Oktokiyok, sang “Amazing Grace” in farewell to her husband. Some days after the funeral service she quietly gathered up Leonard’s clothing and carefully burned them so that the dangerous spirits associated with them would not return to cause trouble among the living.

By the time Leonard Nowpakahok died in 1988, Hughes’s ideas about the island’s cultural survival had already begun to change, beginning with his visit with Leonard in 1979 and continuing through his reacquaintance with the island’s contemporary culture in the late 1980s. In 1979, he saw the village through Leonard’s eyes and through the eyes of the men with whom he had hunted so many years ago. Gambell, then, was not as he had predicted it would become some 24 years after his study.

While I remarked above that Hughes’s experience on St. Lawrence Island had moved into the background and remained there for much of his career, his personal feelings about the island’s future and the cultural survival of its people did change. I believe that his brief renewal of friendship with Leonard Nowpakahok and others in 1979 was personally important to him. That visit probably was the reason that he was invited in 1994 to speak to the community about the role of Elders in traditional Yupik society. On that occasion, people’s warmth and the revisiting of many old friends had a strong emotional effect on him. As I looked at Hughes’s last listing of his publications assembled early in 1997, not long before he died, at the top of his list is the following entry: “Psychosocial analysis of an Eskimo shaman’s life history. Manuscript in preparation.” The manuscript is undoubtedly among his archived papers at the University of Utah and Richard Oktokiyok’s story, perhaps with the help of his granddaughter Amaghalek, who still lives in Gambell, waits to be told.

Charles Hughes’s contributions to Arctic research were many. I think they can be divided into three areas. First, there was his willingness to enter the Arctic to learn from the men and women of Gambell, as illustrated throughout his field notes. Although his reliance on the mission and purpose of the Stirling County Study certainly shaped his search for elements of integration and disintegration, he gathered data in order to build his case in either direction. He was not overburdened at the outset by a theory or philosophy that led him inevitably in only one direction. The military presence was probably the most influential circumstance that shaped his worries about the survival of Sivuqaghmiit culture in the 1950s, and perhaps, too, he had carried into the field what Marshall Sahlins described as “accepting received theoretical oppositions between tradition and change, indigenous culture and modernity, townsmen and tribesmen, and other clichés of the received anthropological wisdom” (Sahlins, 1999:i). Certainly, the task of comparing the village as it had been in 1940 with the village in 1954–1955, with its temporary Army facility and the ominous presence of the Iron Curtain only a few miles away, must have promoted some of the sentiments that Hughes expressed at the end of his book (1960). His work as a whole, however, is not affected by his rather gloomy conclusion, and it remains strong and significant.

Second, there is Hughes’s major contribution to research methodology, noticeable in the methods he used when working with local community residents. Hughes’s whole-hearted embrace of Adolph Meyer’s case history approach combined directly with the recording of life histories as a vehicle for exploring psychosocial and behavioral shifts is but one element of an even more basic method that both he and Jane Murphy seem to have modeled. Throughout An Eskimo Village in the Modern World and in his other publications, Hughes makes use of the term “key informant” again and again. If we look at his and his wife’s three most important key informants, they are Leonard Nowpakahok, Richard Oktokiyok, and Beda Slwooko. It is possible, too, that a fourth critical key informant was the Elder James Aningayou. Hughes relied on him for information about the Village Council, and most likely, he turned to him for a greater understanding of the early religion and the introduction of Christianity into the community. Today, we would certainly refer to these individuals as Native knowledge experts. We would also consider them our research partners, our colleagues, and Native or indigenous scholars. His reliance on these key informants set an example that many have followed.

As I look back, it seems clear that the use of life histories was at the center of the research to which Hughes, Murphy, and the Leightons would all devote their lives. However, only Charles Campbell Hughes is known for his attention to the Eskimo world. Hughes would eventually publish more than 24 articles and 2 books about the North, always with a focus on St. Lawrence Island people. Hughes’s scholarly legacy is exemplified in the sheer range of his contributions, beginning with his early master’s thesis and expanding to include his substantial Gambell research. His work is characterized by his energetic embrace of the life history process as methodology and its partner, culture change. Using this approach, he teases apart what happens as one struggles with the inevitable and sometimes almost unbearable changes to which one must adapt in order to survive.

Hughes’s original research from his St. Lawrence Island year is housed at the University of Utah in the J. Willard Marriott Library and has yet to be explored in depth. The life histories he recorded, his diary of daily events, and his detailed documentation of psychosocial and physical changes await scholars who would be interested in an indigenous community that exemplifies continuous adjustment to contemporary social and environmental change. Hughes’s work offers an accounting of changes in 1954–1955 that can be measured against the combined forces of climate change and ongoing cultural change and modernization with which the community contends in the new century. This holds true whether one approaches his work as non-Native researcher, as a Native knowledge expert, or through some other set of experiences. It continues what I believe is the mission of those whose lives and livelihoods are intertwined with the peoples of the North, be they relatives or strangers. In the coming decades, as northern communities struggle with ongoing social and cultural changes and with the powerful environmental impact of global warming, what a people carry with them into an uncertain future must serve as the cultural and personal foundation that gives them the strength to endure. Charles Campbell Hughes survives through his research as a fine example.

I am extremely grateful to those who knew Charles Hughes for sharing their experiences and knowledge with me. I could not have written this paper without the extraordinary help and critique offered by Jane Murphy, who provided many important details about the St. Lawrence Island study of more than half a century ago.

I am also exceedingly grateful to Leslie Ann Hughes, Charles’s widow, who gave me access to photographs from the 1954–1955 research for use as illustrations. I owe my thanks and gratitude to Igor Krupnik for his continuing support and for sharing his experience with Hughes, to Marc-Adélard Tremblay and his daughter Colette for their words about Hughes during the Cornell days, and to Ronald Simons for sharing his recollections of Hughes during their time together at Michigan State University.

1. As a researcher, Hughes had been preceded on the island by Riley Moore (1913), Aleš Hrdlička (1926), Henry Collins (1928–1932), self-styled archaeologist Otto Geist (1926), and Edward Nelson (1881), among others.

2. Hughes was on the faculty at the University of Utah in Salt Lake City, whereas I was at the University of Washington in Seattle. In spite of the distance that separated us, I feel fortunate to consider him one of my mentors.

3. It was apparently common in the 1950s and 1960s for Ph.D. dissertations and M.A. theses to include a short autobiography of the student author at the beginning of the manuscript. Jane Murphy noted that Hughes’s early upbringing had imprinted him with a deep appreciation for the West and its landscape (Murphy, pers. comm., 2012).

4. Although numerous scholarships now use “national” as part of their name, this was, at the time, the actual title of a particular class of governmental funding.

5. On Alexander Leighton’s professional biography, see Tremblay (2003, 2009).

6. “Stirling County” is a fictitious name.

7. Hughes is listed first among the four principal authors; he participated in most phases of the study, including field interviews, before and continuing after embarking on his own Ph.D. research.

8. Hughes’s curriculum vitae was provided to the author courtesy of the Anthropology Department at the University of Utah.

9. After the Leightons divorced in 1965, Alexander Leighton and Jane Murphy were married. Murphy continued with the SCS and became the study’s director in 1975. Alexander Leighton died in 2007.

10. I have assumed that Dorothea Cross Leighton was also familiar with Meyer’s work and that it influenced her to some degree, although perhaps not in such a major way as it did Alexander Leighton’s work.

11. As part of the research team of the SCS, Hughes traveled to Nigeria to conduct comparative research among the Egba Yoruba (see Leighton et al., 1963).

12. An excellent example of Hughes’s gift for organization is the collection of his research (Charles Campbell Hughes Papers, 1946–1997) deposited in the J. Willard Marriott Library at the University of Utah.

13. “Key informant” as used throughout this paper refers specifically to a term used by Leighton and by Charles and Jane Hughes and is derived from the Stirling County Study methodology.

14. One of the first publications to follow completion of Hughes’s dissertation, even before the publication of the book, was his article on social change in Gambell (Hughes, 1958a).

15. In reading through the responses, I wondered if Hughes was aware that the Yupiget tend to be extremely solicitous of visitors and, when questioned, may give answers meant to please the interviewer/guest to avoid offending by suggesting, for example, that white culture and white ways are not always desirable.

16. In several northern Alaskan and Canadian Inuit communities, the presence of the military, often in association with Distant Early Warning (DEW) Line posts, was common at that time.

17. At the other end of St. Lawrence Island, another base housing an even greater number of soldiers had been established at North East Cape, in conjunction with radar monitoring.

18. Hughes’s article on Eskimo kinship (1958b) argued convincingly for the place of clans in Yupik kinship organization and was somewhat controversial at the time it was published. It is still widely referred to in discussions of social organization among Alaska Eskimo societies.

19. Beulah herself commented that her grandfather had become Christian because his shaman séances frightened her (Beulah Amagheleq Nowpakahok, personal communication, 2005).

20. My emphasis on “the” indicates the singular importance of Beda Slwooko to the project.

21. Beda Slwooko would go on to serve as a Native knowledge expert and consultant in the later years of her life, and many anthropologists sought her out because of her knowledge.

22. Jane M. Murphy’s dissertation is listed in the Cornell University Library under her married name at the time, Jane Murphy Hughes (1960).

23. Hughes’s work took place a year before James VanStone’s (1962) study of Point Hope, Alaska, and several years before Norman Chance carried out research in Kaktovik.

24. Listed in the field experience section of Hughes’s curriculum vitae dated February 1997 (p. 14) is the following entry: “January 1961 through May 1961, Community studies and survey research as part of Cornell-Aro Mental Health Research Project, Abeokuta, Nigeria, of which I was Associate Director, with supervision of social science aspects.”

25. Charles Campbell Hughes and Jane Ellen Murphy married in 1951. The couple divorced in the early 1960s. Prior to the divorce, Jane Murphy’s name appears in publications as Jane Murphy Hughes. After the divorce, it appears as Jane M. Murphy. Following Murphy’s marriage to Alexander Leighton in 1966, she is listed occasionally as Jane Murphy Leighton.

26. Interspersed among these publications were many others addressing issues pertaining not only to the Arctic but also to Nigeria, medical anthropology, and other topics.