CHAPTER THREE

Dakota Landscape in the Nineteenth Century

The Dakota knew Mni Sota Makoce as a network of connected places, each defined in specific ways. They followed a seasonal way of life, hunting game in the woods in winter, pursuing buffalo on the plains in summer, gathering edible plants in the woods and wetlands, fishing in the rivers and lakes, ricing and growing gardens on the lakeshores and riverbanks. Similarly, ritual use of sacred places for burials, ceremonies, and gatherings drew Dakota together at various times of year. Europeans were not present to observe the full seasonal patterns that linked Dakota places. As a result, they often made the mistake of thinking the Dakota were nomads who wandered aimlessly throughout the region. Occasionally they heard Dakota stories connected to places but had little understanding of what those stories and those places actually meant.

DAKOTA ON THE LAND IN THE EARLY NINETEENTH CENTURY

Dakota bands and the villages in which they lived are an important part of the geographic network for the Dakota people in Minnesota. The names of the bands, their villages, and their chiefs are recorded in the narratives of early travelers and in the records of government agents and missionaries, although spellings and translations vary a great deal. Still, the available nineteenth-century records include a more complete picture of the Dakota throughout the cycle of their seasons than is found in earlier documents. As in the earlier British and French accounts, reading between the lines is important.

By the late 1780s trade between the Dakota and Europeans was stabilizing, with fewer interruptions from war and politics. Traders appeared along the Mississippi and Minnesota rivers on a regular basis, supplying the Dakota with goods and encouraging them to hunt and trap. Many of the traders were French or British and were supplied by British companies. They reached the region through Michilimackinac, which was still controlled by the British government, despite the Treaty of Paris, which in 1783 declared it U.S. territory. Following Jay’s Treaty of 1794, Americans occupied the British fort on Mackinac Island but British traders continued to work in the Lake Superior and Upper Mississippi region.1

Both the European traders and the Dakota themselves sought to survive in this changing political environment. In the spring of 1805 British traders Robert Dickson and Rexford Crawford, intending to continue their own trade in the region, took a party of Dakota led by four chiefs, including Wabasha, to St. Louis to meet with Pierre Chouteau, a trader who was also the Indian agent for tribes west of the Mississippi River.2

As a result of this meeting, General James Wilkinson, the new governor of Louisiana, sent Lieutenant Zebulon Pike to the Upper Mississippi to “ascertain the most commanding Sites for Military Posts and to obtain permission for their Establishment in the Spring early,” and to gather knowledge about commerce, waterways, the quality of the soil and timber, and “whatever else may be deemed worthy of Note.” By late August Pike’s party reached the southern limits of Dakota land. He was accompanied by traders long familiar with the Dakota, including Joseph Renville, who was married to a Dakota woman from Kap’oża (or Kaposia), near present-day St. Paul. In the following days Pike visited Wabasha’s village, located on the Upper Iowa River near its mouth; Red Wing village, sited near the mouth of the Cannon River; and the Kap’oża village, then located near present-day Mounds Park in St. Paul. Pike reported the inhabitants of Kap’oża were absent because they were “out in the Land” harvesting wild rice.3

Reaching the island at the mouth of the Minnesota River now named for him, Pike observed a burial scaffold supporting four bodies, “two enclosed in boards and two in bark.” The dead were wrapped in new blankets. He learned that they had been brought from the Minnesota River and from the St. Croix to be buried there. The site could have been Pilot Knob (Oheyawahi), which rises up above the mouth of the Minnesota River. Near Bdote, the mouth of the Minnesota River, Pike was greeted by C̣etaŋ Wakuwa Mani (Petit Corbeau, or Little Crow) with one hundred fifty warriors. They climbed a hill “in the point between the Mississippi and Saint Peters” and saluted Pike and his party by firing off their guns. The next day Pike met with Little Crow and six other chiefs. He gave a speech asking for a grant of land and requesting that the Dakota make peace with the Ojibwe.4

After discussion between Pike and the assembled leaders, an agreement was signed on September 23, 1805. The document (discussed in more detail in Chapter 4) was a treaty with the “Sioux Nation of Indians,” a term used to refer to the Oc̣eti Ṡaḳowiŋ or Seven Fires of the Dakota. The only Dakota signers were Little Crow and “Way Aga Enogee” (Waŋyaga Inażiŋ, He Sees Standing Up), the chief known as Fils de Penishon. His village, later called Penichon’s or Penishon’s village, was located on the lower Minnesota River. Shortly after the treaty signing, Pike set off up the Mississippi to spend the winter among various Ojibwe bands. On April 11, 1806, on his return trip, Pike encountered a village of one hundred lodges and six hundred people at the mouth of the Minnesota River. He met with Little Crow at the mouth of the St. Croix, and on April 13 he gathered with other leaders at the Red Wing village. Farther downriver, on April 21 he met Wabasha and Red Thunder (Wakiŋyaŋ Duta), a Sisituŋwaŋ leader from Lake Traverse.5

In May 1806 four Dakota chiefs and a number of warriors went to St. Louis to meet with General Wilkinson, seeking to cement a relationship with the Americans. Wilkinson tried unsuccessfully to persuade them to go visit with the president in Washington. He wrote to Secretary of War Henry Dearborn that the Dakota had “strong claims to our attentions and courtesy,” but it would be many years before U.S. officials either built upon this relationship or built a fort based on the 1805 agreement.6

The British government and British traders continued to operate unchecked in this part of American territory until after the War of 1812. Fur trader Thomas G. Anderson, who worked in the region both before and after Pike’s visit, kept a record and later wrote a narrative that provides some information on the Dakota. In 1806–7 Anderson wintered about fifty miles above the mouth of the Minnesota, building a post in a strip of timber which he said in some places stretched a mile out from the river. The distance from the river’s mouth would place him near several Waḣpetuŋwaŋ villages, including the Little Rapids village, although Anderson does not identify the Dakota either by village or chief. Game was plentiful in the region that year. The local Dakota were in their hunting grounds most of the winter, returning to the river in March to pay off the credit Anderson had given them in the fall.

The following year Anderson returned to the same location on the Minnesota River, though to very different conditions. It was a mild winter, and deer were hard to track on the bare ground. The nearest Dakota, he said, were fifty or sixty miles away, attempting to hunt for buffalo, which were not plentiful either. Many people were starving. Anderson reported that some had tried to find turtles and other food under the ice in a small lake but had drowned because they were too weak to climb out of the cold water.7

In 1809 Anderson went farther up the Minnesota River to Lac qui Parle, apparently among the Sisituŋwaŋ and Ihaŋktuŋwan. Arriving early in the fall, he joined in a buffalo hunt at Big Stone Lake, where many buffalo were killed. Anderson said little about what happened during the winter but noted that in the spring the Dakota he described as “my hunters” informed him they were not coming to the post to pay off their credits but were traveling two days to the south “on the road to Santa Fe” to trade for horses. Anderson was able to get three-quarters of what he said was due him before they left.8

The next year Anderson returned to Lac qui Parle, where he ran into difficulties because he refused credit to those who had gone for horses in the spring. In the end he would only give them ammunition for hunting, not the other items of trade they were accustomed to receiving in the fall. It was another difficult winter for Anderson because of a shortage of food, perhaps because the Dakota with whom he traded had chosen not to supply him with game. During the course of the season Anderson received visits from the Sisituŋwaŋ leader Red Thunder and another chief named Broken Leg, of the Gens de Perche (People of the Pole) band, probably of the Ihaŋktuŋwaŋ.9

In later years Anderson traded among what he called the Lower Sioux, which he said at this time consisted of six bands, including those of Wabasha, Red Wing, Red Whale, the Six, Little Crow, and Thunder or Red Thunder. Anderson added that Red Thunder was not considered to be attached to any band, which may explain why he included this Sisituŋwaŋ leader among the Lower Sioux. In 1810–11 Anderson had his post on Lake St. Croix. One summer, Anderson stayed at his trading post while his partners went east to Michilimackinac with their packs of furs. During that time Anderson reported the Dakota “were away at their summer villages,” though he provided no other information about them. Later he accompanied an entire Dakota village on a summer hunt on the Upper Mississippi River. Anderson noted that in the fringe of timber above the mouths of the Rum and Crow rivers, the deer would “retire from the scorching sun of summer; and if the mosquitoes are troublesome the pestered animals plunge into the river.” According to Anderson’s account, the men hunted deer while woman and children stopped to pick berries and stretch and dry the skins. Traps were also set for small animals.10

The party soon reached “the borders of their Chippewa enemies,” although Anderson does not say exactly where this was. Though certainly not the usual summer war party, which would not have included women and children, the group prepared for the possibility of hostilities, but none occurred and the party turned back. Later that summer Anderson also described going west with two canoes of hunters to pursue buffalo at Big Stone Lake but added few details about those he accompanied.11

Anderson was involved in fighting against the Americans during the War of 1812, along with other British traders of the region and a number of Dakota, including Wabasha and Red Thunder. Another chief, Tataŋkamani, or Walking Buffalo, chief of the Red Wing village, opposed this involvement. Other chiefs remained neutral.12

Following the war, Americans sought to reestablish relations with the Dakota. On July 19, 1815, government officials signed a treaty of peace and friendship with the “Sioux of the Lakes” (Bdewakaŋtuŋwaŋ) at Portage des Sioux, near the mouth of the Missouri River. The Dakota were brought to the treaty by Nicolas Boilvin, U.S. Indian agent at Prairie du Chien. The treaty stipulated that the signers “acknowledge themselves and their aforesaid tribe to be under the protection of the United States, and of no other nation, power, or sovereign, whatsoever.” The best known of the signers was Tataŋkamani. The same day a similar treaty was signed with the “Sioux of St. Peter’s River.” The following year, on June 1 in St. Louis, a treaty was signed with the “Siouxs of the Leaf [Waḣpetuŋwaŋ, the Siouxs of the Broad Leaf [?], and the Siouxs who shoot in the Pine Tops [Wazikute or Waḣpekute].” Signers of the last treaty, forty-one in all, included some who had signed the other two treaties, including Tatangamarnee (Tataŋkamani). The terminology used to describe these groups was garbled, as were the names of many of the signers, making it difficult to identify the Dakota involved.13

It was not until the summer of 1819, when representatives of the U.S. Army under Lieutenant Colonel Henry Leavenworth appeared at the mouth of the Minnesota River to build a fort, that U.S. government representatives began to have regular contact with the various Dakota bands and villages in the region.

DAKOTA SEASONAL PATTERNS IN THE LATE EIGHTEENTH AND EARLY NINETEENTH CENTURIES

In the 1820s and 1830s seven Bdewakaŋtuŋwaŋ villages were located along the Minnesota and Mississippi rivers. Above Ṡakp̣e’s village on the Minnesota were a number of Sisituŋwaŋ and Waḣpetuŋwaŋ villages, continuing all the way to the headwaters. The Waḣpekute did not usually have fixed village sites but used the region between the Minnesota and Mississippi, along the course of the Cannon River, and the area to the south. Dakota villages were, in effect, summer villages, occupied not year round, but at particular times in the warm months. They were located in the river bottoms, in areas that might be subject to flooding in the spring. Their location reflected a way of life heavily dependent on the river for transportation. The Dakota had horses but continued to rely on dogs and canoes, both dugout and birch bark. The summer village sites were bases of operations occupied sporadically, starting after the rivers had subsided in the spring and continuing until the fall, when the inhabitants left the rivers to hunt for deer.14

As Stephen R. Riggs noted, the Dakota divide the year differently than Europeans do. He reported that, while the Dakota have twelve moons or months to which they give meaningful names, “five moons are usually counted to the winter, and five to the summer, leaving only one each to the spring and autumn.” The two transitional moons corresponded more or less to April and October. Present-day Minnesotans will recognize the logic of the abrupt transition from winter to summer and summer to winter. And like present-day Minnesotans, the Dakota in the nineteenth century “had very warm debates, especially towards the close of winter,” about whether spring had finally come.15

The Dakota use of the land related not only to daily subsistence but also to their beliefs and rituals and the meaning they attached to particular places in the region. Medicine ceremonies, feasts, and Dakota ball games were held at village sites at various times of year. Prominent locations such as Wakaŋ Tipi (Carver’s Cave), Mounds Park, and Oheyawahi (Pilot Knob) were used for burial and ceremonial purposes.

A regular pattern of resources was available in the country of the Dakota, but the changeable weather of every season and every year meant that all resources did not have good years at the same time. In some years the wild rice crop or the corn crop failed. Game was scarce in some places in some years. Through their knowledge of the region, the Dakota were able to harvest some crops or resources more intensively when others failed. For example, it seems the Dakota may have preferred eating meat to fish, but they fished when they needed to.16

To understand Dakota life it is necessary to understand the pattern of seasonal subsistence activities. As will be seen, the Dakota names for the seasons related to the land: winter moons or months connected to animals, while the names for the summer months described horticultural or gathering activities.17

FALL AND WINTER HUNTING

November is Takiyuḣa-wi, “the deer-rutting moon.” Missionary Samuel Pond stated that in October, after receiving supplies of trade goods, larger bands broke into smaller ones and set off for the deer hunt. Pond himself spent several deer hunting seasons with Dakota communities—to learn about the people and their language. He later wrote that in the fall of 1835, “I went off with the Indians on a hunting expedition. The Language however was the game I went to hunt, and I was as eager in pursuit of that as the Indians were of deer.” In the process, Pond had a unique opportunity to be a participant-observer, in the anthropological sense, of Dakota life, beliefs, and social organization.18

Deer hunting took place in backwater regions, up small streams and valleys away from the Mississippi and Minnesota rivers. The Dakota living in what is now the Twin Cities area did most of their hunting on the Sauk River, the Rum River, the St. Croix River, and Rice Creek. This territory was part of a productive area where the Ojibwe, former allies and sometime enemies of the Dakota, occasionally ventured. The region stretched diagonally across the present state of Minnesota north of the Twin Cities. Local Indian agents Lawrence Taliaferro and Henry Schoolcraft and tribal members themselves referred to it as “the middle ground.” On August 18, 1836, Taliaferro met with Ojibwe chief Bagone-giizhig (Hole-in-the-Day), who in a conversation at the agency with Dakota chief Wakiŋyaŋ Taŋka (Big Thunder, known as Little Crow) spoke about the need to share this space: “Let us, said he, to the Sioux, —keep our middle ground clear,” Taliaferro wrote. Keeping it clear meant keeping the peace, since this was a contested zone, a region where Dakota and Ojibwe battled in summer but which they shared in winter, a season when they rarely fought.19

Dakota bands departed the rivers to go to their hunting grounds in September or October, after ricing had been completed, not returning until after the first of the new year. On October 31, 1830, Taliaferro reported that he held a council with the Dakota and Ojibwe “to settle their differences for the winter.” They left the next day to “go off on their hunts.” He added, “Nothing I hope will disturb their mutual intentions for the winter.”20

A few hunting locations were associated with particular Dakota villages. The Kap’oża village usually hunted along the St. Croix River, sometimes going as far north as St. Croix Falls. The area was more easily accessible to them by overland travel than through the circuitous water route down the Mississippi to the mouth of the St. Croix. In December 1835, translator Scott Campbell returned to Fort Snelling from the St. Croix River, reporting to the agent that “The Sioux & Chippeways were below the falls of St. Croix—on the Chip Land by invitation—Dancing—playing Ball & feasting together.”21

Waḣpetuŋwaŋs from the Little Rapids village of Mazamani were reported in 1828 hunting on a small lake near the head of the Sauk River. In 1831 they hunted between the Crow and Sauk rivers, reaching an agreement with the Sandy Lake Ojibwe for the winter. The Black Dog village and Cloud Man’s village usually hunted along the Rum River, making arrangements with the Rum River and Mille Lacs Ojibwe. Samuel Pond accompanied a hunting party from Cloud Man’s village in the winter of 1836 that traveled along the Rum River.22

The people of Wabasha and Red Wing villages usually hunted inland, either to the north in the area of present-day Wisconsin along the Red Cedar and Chippewa rivers or west in the rich region of present-day southeastern Minnesota, along the headwaters of the Cannon, Zumbro, Root, Blue Earth, and Des Moines rivers, an area known as Waḣpekute territory but shared with other Dakota bands. According to Joseph Nicollet, the convergence of the Des Moines and Blue Earth rivers was known as Mni Akipam Kaduza, meaning “water running to opposite sides.” Throughout this region Dakota might encounter the Sac and Fox, with whom they were sometimes at war. Here too, Lawrence Taliaferro attempted to reduce friction between groups in an intertribal area known as the “neutral ground.” Ultimately several treaties were required to sort out tribal claims, but the uncertainties there, as with the area between the Dakota and Ojibwe, reduced access and increased game populations, which made the area desirable for hunting.23

Dakota bands traveled through their hunting grounds regularly, never returning to an area more than every two or three years, according to Samuel Pond. Whole communities of men, women, and children traveled together in these hunting parties, covering a short distance each day. Travel was on foot, with horses—if the community had them—pulling travois frameworks carrying the heaviest loads. Hunters forged ahead looking for game, while the rest of the party followed, taking down the tepees and setting them up in a new place. The social organization of the deer hunt, as described by Samuel Pond, resembled the complex organization of buffalo hunting for Dakota on the prairies: “The movements of a hunting party were regulated by orders issued by the chiefs, or, if no chief were present, by one of the principal men of the party. These orders were given out after the wishes of a majority of the party had been ascertained by consultation, and were commonly proclaimed by a herald in the morning or evening, the only time when the hunters were likely to be all at home.” To make sure the whole community was fed, special rules applied to what happened to the deer that were killed. Game was divided among all hunters who claimed a portion even if they did not shoot the deer, though the hunter who killed the deer was always allowed to keep the skin.24

During some years in both winter and summer, people from Black Dog village hunted to the south in the region of the Waḣpekute, which bordered the territory of the Sac and Fox, sometimes subjecting them to the threat of warfare. Although the herds of buffalo had receded to the west since the beginning of the nineteenth century, there were years when buffalo were still seen in this region. In June 1827, Wambdi Taŋka (Big Eagle), chief of Black Dog village, left with Wabasha’s son-in-law, who had some connection to the village, to hunt on the Des Moines River. Later in the summer Taliaferro reported that the Black Dog chief, with seven lodges of his band, was still on the plains and was rumored to be going as far as the Coteau de Prairie, though he might return in the fall to gather rice on the Cannon River. Cloud Man, or Maḣpiya Wic̣aṡṭa, the Black Dog war chief, was on his way back to the village on the Minnesota River with three lodges. On his return he gave Taliaferro an account of what had occurred during the summer hunt, although Taliaferro recorded no details.25

On May 6, 1829, Wambdi Taŋka returned with his followers “from his hunt on the Des Moines River,” where they appear to have spent the whole winter. In September 1835 Wambdi Taŋka’s son Maza Ḣota (Gray Iron) visited the agent prior to departing for the same region. Taliaferro asked him to transmit a message of peace if he encountered Sisituŋwaŋ and Waḣpetuŋwaŋ people during the winter.26

This may have been the hunting trip recorded in the life story of Joseph Jack Frazer or Ite Maza (Iron Face), the son of a white trader and a Dakota woman whose name is recorded as “Ha-zo-do-win,” a daughter of Tataŋkamani (Walking Buffalo), the chief of the Red Wing village. Frazer grew up with his mother’s family and as an adult remained part of his grandfather’s band but was married to a daughter of Maza Ḣota, by then chief of Black Dog village. According the narrative of Frazer’s life recorded by Henry H. Sibley, one winter in the 1830s when Frazer and his uncle Wakute wintered on the headwaters of the Root and Whitewater rivers, they were joined by Maza Ḣota. When the Black Dog leader set off to return in the spring, Frazer accompanied him as far as Pine Island on the headwaters of the Zumbro River. There he also met his friend Ta Oyate Duta, son of Wakiŋyaŋ Taŋka, who had by then succeeded his father, C̣etaŋ Wakuwa Mani, in the leadership of the Kap’oża band. The two men hunted for several weeks before Frazer and his wife returned to the Root River.27

The chief of Penichon’s village also hunted in the region of the Des Moines River. In July 1831 Taliaferrro wrote in his diary that he would “send Penition Chief to hunt with the Sioux on the Des Moines this fall and all winter until spring—so as my councils may be continually repeated,” a reference to his attempts to foster peace with the Sac and Fox.28

Taliaferro’s journal mentions the killing of other game in the fall. In August 1835 several bear were spotted on the “9 mile ridge creek [possibly at Kap’oża] within a few days past which fact seems to revive the drooping spirits of our neighboring Indians as Game has been considered scarce this season.” The next month ten bear were killed in the cornfields at Cloud Man’s village on Lake Calhoun. Taliaferro reported, “This put the Indians in fine spirits—& their Corn was gatherd the faster & with more pleasure.” At the same time he noted that “the high winds has blown down the wild rice—unlucky.” Taliaferro explained the presence of so many bear by a lack of food farther north. He also noted that raccoons were overrunning the agency gardens.29

Muskrat hunting was mainly a spring activity, although sometimes the animal was hunted in the fall. In 1835, when muskrats were “unusually abundant,” people killed “40 to 60 per diem.” There are only a few references to buffalo hunting, usually by Dakota bands farther west. On March 3, 1828, the Odawa and French trader Joseph LaFramboise arrived at Fort Snelling, reporting hard winter conditions along the Sheyenne River, in present-day North Dakota. He stated that ten lodges containing fifty people had died, probably from lack of food, “the snow being so deep that they could not pursue the Buffalo.”30

During the winter, chiefs sometimes returned to Fort Snelling to meet with the agent and the traders and pay for the credits of trade goods given them in the fall. In some cases the elderly and infirm were left by their bands near the Indian agency so they could receive aid from the agent when necessary. Toward the end of his time at Fort Snelling, Taliaferro stated that over the years he had aided thousands of Dakota and Ojibwe, at his own expense. For example, in March 1836, with the temperature at twelve and a half degrees below zero, Taliaferro received a visit from a Waḣpekute woman whose name he did not know, along with her children and others in need. The woman presented him with a pipe and spoke about her relationship to two prominent Waḣpekute leaders:

My Father—I have called to see you with my family & friends to shake hands with you. my child[re]n shake ha[n]ds with your Father—I am connected with the Chief Tah saugah [C̣aŋ Sagye, or Cane] of the Wah paa kootas [Waḣpekute] & also with Wah maa de sappah [Wambdi Sapa, or Black Eagle], you see me poor and miserable my friend gone by the hands of his enemies and his children left for me to provide for. We are without a Blanket. Scarcely a petty coat and as you see dirty and in great want.

Taliaferro gave “this family 6 or 8” rations of beef and pork, along with tobacco and four bars of lead for making ammunition. He said it was all he could spare.31

In some cases, however, staying near the fort could be a problem, especially for women, who might be molested by soldiers. In December 1827 Taliaferro wrote that the soldiers were “troublesome to the Indian women who are encamped near the Agency—their husbands & friends being out hunting.” Taliaferro aided them by driving the soldiers away. Generally, he advised the visiting Dakota to stay away from the garrison at the fort.32

SPRING SUBSISTENCE

The deer hunting season continued through November and December and into January. At that point, if the hunt had gone well the community would usually have a large surplus of dried meat. At this time of year deer were becoming lean, so bands left the hunting grounds and moved closer to the summer villages, where they set up tepees in a sheltered area.33

Now was the time for fishing or spearing through holes in the ice for “Pike, Pickerel, Black bass, & Sun fish in all their varieties,” according to Taliaferro. Dakota who lived along the rivers, such as the Black Dog and Kap’oża villages, fished and speared in the lakes in the floodplain—or “ponds,” as Taliaferro called them. In late March 1836, Taliaferro noted he saw Dakota fishing in “adjacent ponds in groups of 8 & 15—cutting from the ice, fine pike, pickerel, sun fish, &c &c.” From the agency he could have seen Snelling Lake, just below the bluff; across the Minnesota River to what was then known as Prescott’s Pond (destroyed by a new river channel in modern times); and upriver toward what are now called Gun Club and Long Meadow lakes. The blacksmith at the Indian agency often supplied spears or repaired them for the Dakota.34

Samuel Pond wrote that this was a season of rest, assuming the deer hunt had been successful. It ended in March when the Dakota went to hunt or spear muskrats and make maple sugar. These activities required members of the community to split up because the muskrats and the maple trees were located far apart. Pond wrote, “A few of the women accompanied the men to the hunting ground, and a few of the men staid with the women at the sugar bush, but the men were the fur-hunters and the women were the sugar-makers.”35

Conflicts over the use of maple sugaring sites occurred during the 1820s and 1830s as demand for firewood expanded from the area close to Fort Snelling. Soldiers apparently sometimes tapped the trees themselves as well. In March 1829, one Dakota leader stated in a discourse with Taliaferro,

My Father

We are poor people raised in the woods. We have no rights perhaps—but what we think ours we hope will not be taken away from us without our consent. The Other War Chief (Col Snelling) and you my Father promised not to let any person interfere with a Small piece of ground where our women go sometimes make a little Sugar. You promised us this when the Soldiers made Vinegar on it one year.

A few days later the family of Dakota interpreter Scott Campbell returned from a sugar camp to say they had been “ordered off by the Soldiers of Lieut. Jouetes Company.” Taliaferro reflected in his journal on the difficulty of sorting out the laws when public officials were involved.36

Not all of the locations where Dakota went sugaring have been recorded. One known site was Nicollet Island just above the Falls of St. Anthony in Minneapolis. A Hennepin County history describing the area in 1842 states that the island was “covered with magnificent maple trees,” supplying three or four sugar camps for Dakota people, including those from the Cloud Man and the Penichon (Good Road) villages. Location on an island was said to provide “plenty of moisture” for the trees, making the sap abundant. Later, army officer Seth Eastman painted a view of Dakota women at a sugaring site, perhaps on Nicollet Island. Lieutenant James Thompson’s 1839 map of the Fort Snelling reservation marks one “sugar orchard” along the west bank of the Mississippi River below St. Anthony Falls, possibly near the present location of the University of Minnesota. According to Taliaferro, there was also a maple grove near Minnehaha Falls, which was known at the time as Little Falls, and the area around Wakaŋ Tipi (Carver’s Cave), near the Kap’oża village, had a “sugar forrest.” Waḣpetuŋwaŋ from Little Rapids may have gathered sugar in the area between the Sauk and Crow rivers, where they also sometimes hunted in winter. Several early settlers of Wright County, in Maple Lake and Albio townships, recall visits from groups of Dakota who gathered sugar on the settlers’ claims in the 1850s. Likely many other locations were used by the Dakota for sugaring in the mixed woodland areas around the Twin Cities and throughout the Minnesota and Mississippi river valleys.37

While the women gathered the sugar, the men hunted muskrats, the staple of the Dakota fur trade in the nineteenth century. The Minnesota River valley was well populated with muskrats, even while beaver were in decline. Many Dakota traveled long distances for the hunt. Indians living in the area of Bdote might travel hundreds of miles to go and return from the Upper Minnesota River. As Pond wrote, spring was the best time of year to hunt muskrats because as the sun melted the snow and ice, muskrat houses thawed out more quickly than the surrounding areas because of their dark color, making them easy to find. To kill muskrats the Dakota used axes to break open the muskrat lodges and barbed spears as well as traps and guns to kill the inhabitants. Pond wrote that many of those seeking muskrats survived on muskrat meat during this season of the year. He noted that the meat was edible in small quantities during cool weather but spoiled quickly in warm weather and that the carcasses gave off a rank, musky odor.38

Pond stated that even if the Dakota had the opportunity to hunt waterfowl at this season of the year, ammunition was often too precious, because the Dakota depended on muskrat furs for much of their trade. Taliaferro mentions the Dakota hunting geese and ducks, especially in areas he could see nearby, such as “the pond near the fort,” probably a reference to Snelling Lake. In March 1828, Taliaferro wrote that he saw the first geese that morning and that “the Indians ran out of their Lodges in every direction expressing their delight at the occurrence this early.”39

For Taliaferro, as well as the Dakota, the appearance of migrating waterfowl was a signal of transition, the coming of spring or the nearness of winter. In March 1828, he wrote of seeing geese: “Indians from all the Lodges within the Vicinity of my house ran out to express their delight at the certain omen of a Speedy Spring—or rather b[r]eaking up of the Ice on the Rivers.” On April 4, 1836, Taliaferro wrote,

This day is so fine that the Inhabitants & military are like the Bees, & ants b[u]sy flying about & others sunning and thawing out after a long & tedious winter.

Many stragling Indians also to be seen who are smiling at the prospect of spring—& the appearance of wild geese Ducks &c &c40

On March 22, 1828, Taliaferro stated, with a typical lack of understanding, that Dakota people who had just carried out a “Medicine feast” presented him with the first goose killed that month: “This is one of their many Superstitions always to make a feast of the first Animal Killed at the commencement of each Season.” Other early observers noted that the Dakota held such feasts for the first corn and wild rice, celebrating the arrival of each season’s resources.41

The inhabitants of the settlement closest to the fort, Black Dog village, were known as Marhayouteshni (Maġa yuṭe ṡni), “those who do not eat geese,” a possible reference to the fact that even though they lived in an area known for massive migrations of waterfowl, they did not eat them, but reserved them instead for trade with the officers at Fort Snelling. On March 28, 1828, Taliaferro wrote of a late snowstorm, mentioning “frequent changes in the weather” and “Ducks—Geese &c in great abundance brought in this day by the Indians.” The next year, on April 10, he wrote, “Mild and pleasant weather this morn[in]g—Indians commence to Kill wild geese.” A few days later he noted that “Fish—Geese—Ducks are brought in by the Indians to trade at the Fort.” The presence of the chief Kaḣboka, from Black Dog village, provides a clue to which bands were killing and trading ducks and geese.42

Dakota communities more distant from the agency also hunted waterfowl in spring or fall. While traveling down the Mississippi in October 1821, Taliaferro noted he “Passed the Band of Chief Warbeshas—on an Island engaged in putting up their tents—with a view to hunt Ducks Geese Deer &c for a short time.”43

Spring hunting and trapping for furs did not occur in winter hunting areas but along river valleys, sometimes to the west. During one productive season, in May 1836, Taliaferro reported that Maḣpiya Wic̣aṡṭa (Cloud Man) had returned with several others “from the plains” with eight hundred to five thousand muskrats between them.44

On their return to the area of their summer villages in the spring, Dakota people held medicine dances. Joseph Nicollet described such an event in frigid conditions on Pilot Knob on February 15, 1837; Taliaferro recorded these ceremonies occurring in February and at other times of the year. On some occasions the Dakota welcomed observers from the fort at locations including Pilot Knob, Carver’s Cave, Lake Calhoun, Lands End (near the present-day entrance to Fort Snelling State Park), Pike Island, and other sites “near the agency.”45

The Dakota medicine ceremony, the Wakaŋ Wac̣ip̣i, was similar in many ways to that of other midwestern tribes. On June 12, 1834, Taliaferro reported, “A large body of Sioux have a medicine ceremony and dance at Lake Calhoun this day. Some Chippeways were invited and attended.” In addition to medicine ceremonies, Taliaferro refers in his journal to many dances and ceremonies, often given in front of the agency house for assembled visitors. Yet, Taliaferro provides little specific information. Though he was a keen observer of Dakota customs, his knowledge of their ceremonial life was not sophisticated.

Another important marker of spring’s coming was the breakup of ice on the rivers, especially because rising water could flood the sites of summer villages. One particularly bad year was 1826, when in April, as the ice melted, the waters on the Mississippi and Minnesota rivers rose as much as twenty feet above normal, covering most of the houses and government buildings near Fort Snelling on the river flats, including the trading post run by Jean-Baptiste Faribault on Pike Island.46

According to Taliaferro, the 1826 flooding also swept away the Penichon, Black Dog, and Shakopee villages. This may explain why, when the river started rising in March 1828, local Dakota were “busily engaged in moving their Lodges from the banks of the River St. Peters upon the contiguous Bluffs—it being rapidly on the rise,” even though ice on the two rivers was still firm.47

Another regular spring occurrence was the burning of the prairies. In April 1828 Taliaferro reported “Extensive fires in every direction. The Pra[i]ries are and will be burnt over—much damage to the under growth & trees. The fact of the origin of the extensive plains in the north and west may be ascribed to the yearly inroads made by fire on the wood Lands.” The previous year he had noted that native people employed fires to aid in hunting, writing, “The moment they Start upon their Winter or fall hunt, they set fire to the Prairies—which starts off the Game in every direction, to avoid otherwise certain destruction.”48

On other occasions Taliaferro suggested burning was practiced by both the Indians and the military. The soldiers may have intended to improve grazing areas and make the land easier to plow in the open prairie west of the fort. On October 11, 1835, Taliaferro wrote that the commander of Fort Snelling, Major John Bliss, had set out at sunrise “with 50 or 60 men to set fire to the Pra[i]rie. Rather wet for fire at this hour. The policy of Pra[i]rie burning may be questioned, at any rate I have order[e]d the Indians in the most positive manner not to set fire or permit their children to fire the Pra[i] rie on any account—for it is sure to burn up the fenceing, wood choppings—Hay stacks & again the Cattle suffer & horses, and the game is at once driven off to a great distance.”

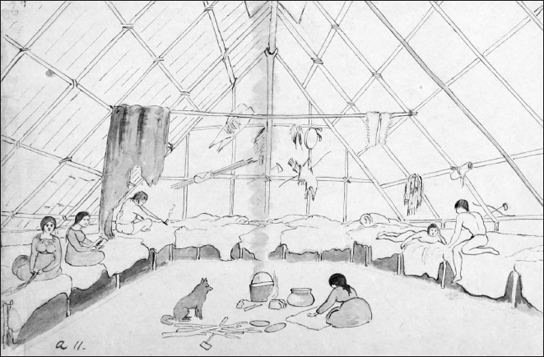

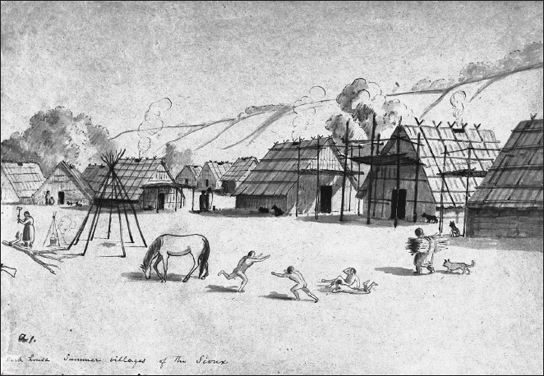

The platforms used for beds inside the bark houses of a Dakota summer village were recorded by Robert O. Sweeny in the 1850s.

SUMMER JOURNEYS AND FALL HARVEST

In May the sugar makers and the muskrat hunters finally returned to the villages along the rivers and began to live in summer houses, which consisted of gabled structures made of a pole framework covered with elm bark. These houses had a built-in platform at bed height all around the perimeter of the structure.49

For the next few months, meat resources were scarce. Summer hunting was shorter and more sporadic than in winter, though it sometimes covered the same territory. On June 19, 1827, Taliaferro stated, “The Sioux Bands near this Post have generally left for their Summers hunt.—and will remain some thirty or forty days. Some of them will go in the direction of the Chippeways frontier, may expect to loose their Scalps.” Hunting in the summer was more dangerous because it was frequently a time for war parties. In July 1817 explorer Stephen Long noted the residents of Cetaŋ Wakuwa Maŋi’s Kap’oża village were absent on a hunting party up the St. Croix River. Given the season, there could have been many other possibilities. In July 1823, William H. Keating, a member of Long’s second expedition, stated that the Kap’oża village was “abandoned for the season,” giving no other details. The people from Kap’oża hunted on the Crow River in the summer of 1834. In June 1829 Kaḣboka of Black Dog village hunted on the Sauk River, while Wambdi Taŋka, Big Eagle, hunted on the St. Peters River.50

In July 1827 Taliaferro noted that the chief of Penichon’s village and others of his band were “on the plains in pursuit of subsistence.” Traveling up the Minnesota River in mid-July 1823, Long’s expedition encountered the chief of Black Dog village not at his home but with family members over a hundred miles away, close to the Cottonwood River near present-day New Ulm. In September 1835 British geologist George William Featherstonhaugh stated that the members of Black Dog village were “on the prairies hunting buffalo.”51

In some cases men could not get ammunition to hunt in the summer because traders were unwilling to supply it until the time of year when animal furs were thickest. In June 1827 Taliaferro stated that some families had little to eat during the summer until corn ripened in August, unless they obtained wild plant foods. Starting in the 1830s the Dakota were promised the payment of treaty annuities, which persuaded them to camp near Fort Snelling rather than go out hunting. Delays in payment led to summer scarcities. At such times and at other occasions during the year, the Indian agency supplied food, ammunition, and other provisions, such as fish hooks and lines and spears.52

For the Dakota, June is Ważuṡtec̣aṡa-wi, “the moon when the strawberries are red,” while one name for July is C̣aŋpasapa-wi, “the moon when the chokecherries are ripe.” In addition to berries and fruits, many wild plant foods became available in the spring and summer, including tipsiŋna or wild turnips, and mdo, a kind of potato. Other food plants included the pṡiŋc̣iŋc̣a (psinchinca), a round root the size of a hen’s egg, and the pṡiŋc̣a (psincha), a spherical root an inch in diameter, both of which grew in shallow lakes and marshy ground including the wetlands bordering the Minnesota River. Pond noted that these roots were harvested by women standing in the water: “When a psinchinca is detached from the mud it immediately rises to the surface of the water; but the psincha does not float and must be raised by the foot until it can be reached by the hand, a difficult operation, requiring much dexterity where the water is up to the arms as it often is where they grow.” Pond recalled, “scores of women might be seen together in shallow lakes, gathering these treasures of the deep.” It appears these roots provided food at various times of year when other resources failed. On April 30, 1829, Taliaferro wrote that “the Indians are now Subsisting entirely on Wild or Marsh Potatoes—without Salt or grease of any Kind whatever—(a poor diet).”53

Summer was a time of great sociability among the Dakota, when larger bands were reunited. In earlier eras, going back to the 1600s, the mouth of the Minnesota had been a location where western and eastern Dakota bands met. With the building of Fort Snelling and placement of the Indian agency there, an extra dimension was added to its traditional role. Starting with the first treaties, annuity payments were often made during the summer at the fort, drawing those from all the Dakota bands involved.

The area around the fort was often the site for Dakota ball play, or lacrosse, between Dakota villages and between Dakota and Ojibwe. On July 4, 1835, various Dakota villages played ball on the plain near the fort for the amusement of artist George Catlin, who was visiting the area. Catlin painted portraits of some of the players.54

If Dakota villages grew corn, it was planted in June, when strawberries were ripe, usually on ground “where there was a thrifty growth of wild artichokes.” Dakota women planted corn in hills, not in rows of plowed fields as whites did. Pond wrote that many Dakota villages did not grow more than enough corn to feed the community for a few weeks. Often they ate all the corn in its “green” state—that is, fresh from the cob, at its sweetest. Some corn was dried and put in bark containers for winter sustenance, but because Dakota made use of many other resources it was not common for villages to store large quantities of corn.55

During his time at Fort Snelling, Taliaferro sought to encourage a shift among the Dakota to increased dependence on agriculture—particularly the growing of corn—which he saw as a crucial step in instructing them in what he viewed as “the arts & habits of civilized life.” These included the use of plows and men’s participation in agricultural activities usually carried on by Dakota women. Taliaferro urged the chief Cloud Man, who had been a member of the Black Dog band, to move to Lake Calhoun and establish an agricultural colony which would grow not only corn but other crops, such as beans and squash.56

As a result of Taliaferro’s influence, the people of that community appear to have adopted plows in preparing the ground for growing corn, but the work of cultivation was still carried out mainly by the women. Taliaferro himself made use of the agricultural skills of Dakota women, hiring some to work in his garden at the Indian agency. In 1839, the final year Cloud Man’s band was at Lake Calhoun, missionary Gideon Pond left a detailed description: “The Ind’s at this village plant about 80 acres (I plowed only 15 acres for them this spring) as it has all been planted before it is comparatively easy for them to cultivate it with the hoe.” He noted that “the women do mostly some of the men however help their wives through the whole of it (the corn belongs to the women),” making the same point about corn that Jonathan Carver had made about women’s harvesting of wild rice seventy years before. Pond noted that in 1839 the village had harvested about 2,300 bushels of corn and two hundred bushels of potatoes. Finally, he wrote, “Each woman has her little field to take care of. The 80 acres which they plant is divided into 50 fields yet all lies or nearly all together.” He did not say whether the women at Cloud Man’s village grew their corn in hills in the traditional way, but a map of the area drawn by Taliaferro in the 1830s suggests the fields were divided up irregularly rather than in rectilinear plots.57

Dakota who did shift more intensively to growing corn did not abandon hunting or food-gathering. It would have made no sense for people in the Minnesota country to attempt to survive on only a few agricultural resources. Even later white settlers did not try to do so. Pond went hunting with Dakota from Cloud Man’s village at Lake Calhoun and wrote that while they waited for their corn to ripen, they could often be found catching bullheads in Mud Lake, now called Lake Hiawatha, along Minnehaha Creek above the famous falls.58

During the same period, other bands grew crops as a supplement to hunting and gathering. In 1835, Mazamani of the Little Rapids village asked Taliaferro for aid in getting his lands plowed “as others are.” He also asked “for our women a corn Mill as our women find it hard to beat their corn after our fashion,” suggesting his band did not intend to change gender roles as urged by the agent. Even Waḣpekute bands, usually described as nomadic, grew some corn, though it is not clear whether this practice was influenced directly by the example of Cloud Man’s village. In May 1836, Skush Kah Hah (possibly Ṡkaŋ ṡkaŋ yaŋ, or Moving Shadow) of the Cannon River Waḣpekute visited the Indian Agency at Fort Snelling. Taliaferro wrote, “We had considerable conversation as to his people & his fears of the Sacs & Foxes had induced them to leave the Cannon River for this season only to raise their corn on the St Peters 7 miles up this River & asked for shoes &c.” However, the Waḣpekute did not adopt agriculture in the fashion of whites, as an activity for men. The leader told Taliaferro, “My Father—we call for a few hoes to enable our women to break the ground and I hope you will spare us some as we are much in want of such things, we wish also for a few fish spears—& files—& fish hooks & lines if you have any.”59

Other villages—such as Kap’oża and Black Dog, from which the people of Cloud Man’s village had originated—followed the agricultural village’s example more directly. In March 1836, Wambdi Taŋka came to see Taliaferro at the agency: “He asked for a plough & chains & harness—to open a farm at his village, his family & friends had (10) horses. His son, & nephew were active men and would attempt to plough themselves if I would start them with the means &c.” Taliaferro promised to provide him with a plow and harness.60

A similar agricultural experiment was taking place at Lac qui Parle, where the trader Joseph Renville and missionaries Thomas Williamson and Stephen R. Riggs also sought to convince the Waḣpetuŋwaŋ to grow more corn as a way to avoid food shortages. Some of the Waḣpetuŋwaŋ had moved from the villages near Little Rapids to grow corn at Lac qui Parle. However, their experience provided a cautionary tale about the difficulties involved in depending on any single resource in the Minnesota climate when on June 20, 1842, a very late frost killed all the garden crops. Many of those living at Lac qui Parle were forced to move back to the lower Waḣpetuŋwaŋ villages to stay with relatives. The following year a drought made things worse. Williamson, usually stationed at Lac qui Parle, spent part of that time at Fort Snelling. In May 1843 he wrote that more than half the Indian members from the Lac qui Parle church spent half the winter within fifty miles of Fort Snelling. More than a dozen came to his church services from January until April. Many expected to stay in the lower Minnesota River valley and plant that spring. Williamson stated, “One principal object which I had in view in coming here was to procure some aid for those who came in this direction in consequence of the failure of their crops. My success in this respect exceeded my hopes but not their expectations.” The government granted them $2,500-worth of blankets, guns, ammunition, and a large surplus of provisions. At the same time Williamson was filling in for the doctor at the fort and was paid sixty dollars per month.61

One way or another it was clear farming was not a panacea, and the agricultural way of life was never fully embraced by Dakota communities. In 1839 an elderly Dakota man at Lac qui Parle told missionary Riggs about his recollection that when he was a boy corn was first planted below Fort Snelling on the Minnesota. Generally, “as soon as it was fit to eat they devoured it all.” In addition they hunted buffalo and deer and gathered wild rice. According to the account, “they raised no more corn until he was a young man. Then some relatives planted a small patch. The next year his relatives planted a small patch and a number of others planted also. Thus the number who made corn increased every year and their fields were enlarged a little. Other villages along the Saint Peters River, following their example, planted corn.” The Treaty of 1837 provided funding to pay for government farms run by government farmers adjacent to many Dakota villages, designed to provide food and to encourage farming by the Dakota. Even among the Dakota who embraced agriculture, however, traditional resources remained important.62

Late in the summer was the time for ricing throughout Dakota country. The Dakota equivalent of September is Psiŋhaketu-wi, “the moon when the rice is laid up to dry,” while October is Wi-ważupi, “the drying rice moon.” The Dakota relied on wild rice as a major resource during the winter. The rice crop was variable, depending on water levels. Many lakes around the Twin Cities, including some in present-day south Minneapolis and along the Minnesota River, had thick beds of wild rice. The Rice Creek corridor in present-day Anoka, Ramsey, and Washington counties provided the Dakota with a great deal of rice. Whole bands went to the ricing places in late August or early September. Dakota people obtained birch-bark canoes in trade from Ojibwe who came to Fort Snelling to visit the Indian agent. Taliaferro noted in his journal on June 10, 1829, “These light canoes are in great demand among the Sioux—who use them in gathering the Wild Rice from the Lakes & Ponds adjacent.” In August 1827 Taliaferro warned that Dakota who had neglected their corn crops “must look out for rice or starve nearly during the approaching winter.”63

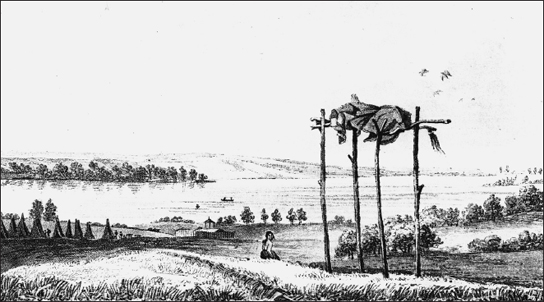

Like many Dakota village sites, the one at Lake Traverse recorded in 1823 by Samuel Seymour had burial scaffolds on a nearby hill.

Cranberries were another important crop in the fall. On October 12, 1835, Taliaferro reported, “Cranberries brought in—high prices paid—by the citizens for transportation to the lower country.” In April 1826 he also reported cranberries, possibly dried, being brought to the post. On his departure from the agency in the fall of 1839, Taliaferro included among his effects on board the steamboat Gypsey one barrel of cranberries. Later on, during early white settlement, cranberries harvested by Indian people continued to be an export item from the Minnesota region.64

Sporadic hunting and fishing also supplemented the gathering of wild plant foods. Spearfishing took place all along the rivers near Fort Snelling. One summer fishing place for the people of Kap’oża was at Grey Cloud Island, near Pine Bend on the Mississippi. In September and October some trapping was done, although it is not described in much detail. Taliaferro in his journal mentioned that the Kap’oża band went above the Falls of St. Anthony to hunt for beaver in late September 1831, intending to stay there until traders arrived with merchandise for credit.65

Prior to departing for the winter hunting grounds the Dakota had more ceremonies, though Taliaferro did not always describe them with a great deal of understanding. On October 12, 1835, he gave a puzzled and puzzling account of what he observed by moonlight:

The Indians as late as 7 oclk began Danceing any and [all] kinds of figures of a rude nature—Buffalo—first then—War—Discovery—beg[g]ing and last of all the fence dance—intermixed with Medicine ceremonies—fireing at the Devil—all in great glee—men, boys, women and girls—all by a slight ray of the moons beams. From what I could learn from the speakers remarks alias—captain of the Dance & master of the ceremonies—The Agent is likely to have a general Visit on tomorrow Tuesday.

Some of the dances mentioned, including the buffalo dance, the discovery dance, the war dance, the begging dance, and the medicine ceremony, have been described in various sources, but the reason for the dance taking place in the moonlight and whether it was intended for the benefit of the agent or the soldiers is unclear.66

Taliaferro did receive a visit the next day, not from the Dakota but from the fort’s commander, Major Bliss, who complained about the Indians’ continuing presence around the fort. By late October or early November most of the Dakota villagers had left to go hunting for the winter, not to return until February or March. As Taliaferro put it a few weeks later, on November 4, “Cold rain, and disagreeable weather. The Indians haveing finished their fall hunt—Depart generally for their winter hunt—usually return 1st March—after which the usual spring hunt is commenced. Divided into Fall,—Winter, spring,—summer.”67

The seasonal cycle never ended, but it did vary from year to year depending on weather, war, and rotation of land use. Managing the cycle required the combined knowledge of many band members, who passed on their experiences through the generations. The record kept by Taliaferro and the missionaries and other whites provides a rich view of the Dakota relationship to the land, as it was then, as it had been, and as it would soon cease to be, in the era after the Dakota land cessions and the devastation of 1862–63.

DAKOTA BALL PLAY

During the summer and at other times of the year Dakota villagers traveled throughout Minnesota to each other’s villages to play ball games. These games were associated with many aspect of Dakota culture and highlight their strong connection to the land and the places they lived within it. Views about the ball games varied widely depending on the writer’s perspective. Missionaries and government agents saw the game in simplistic terms, often with little sympathy or cultural understanding. Not until Dakota writers such as Charles Eastman gave accounts of the game was it possible for non-Dakota to view it with a fuller cultural understanding.68

Dakota ball play, or Takapsic̣api, often called lacrosse, from the French name for the racket used in the game, was a feature of Dakota life often described by early European visitors and missionaries. Using the takapsic̣api, a hooped ball racket or club, and tapa, the wooden ball, Dakota men and women played energetic games in summer and winter, for their own entertainment and that of visitors. One of the earliest written accounts was given by Joseph Marin, who reported that the Dakota played for several days against the Sac and Fox near his trading post on the Mississippi in December 1753. On his trip down the Mississippi in the spring of 1806, Lieutenant Zebulon Pike stopped at the present site of La Crosse, Wisconsin, the location of a prairie where native people often played the sport. On April 20, 1806, Pike observed a game between the Dakota and the Ho-Chunk and Fox. Pike described the ball as being made of a hard substance “covered with leather.” The game was played on the prairie, with goals in the form of a line marked a half mile apart. Pike, like other observers, did not indicate if there were boundaries on the sides of the field, though riverbanks or forests may have created natural boundaries. According to Pike the “parties” wagered “the amount of some thousand Dollars.” The object was to carry the ball across the opponent’s boundary four times. Players tried to get the ball into their rackets, running with it toward the goal but flinging it great distances when necessary. Pike stated that in the game he witnessed “the Sioux were the conquerors,” not for their running ability but “from their superior skill in throwing the Ball.”69

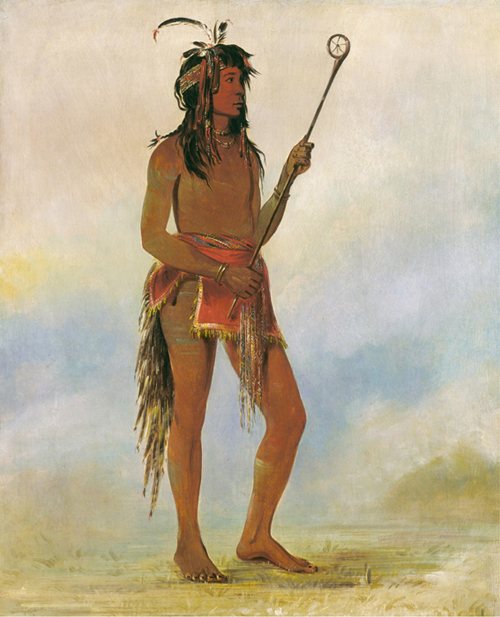

Robert O. Sweeny made this drawing in the 1850s of Dakota people playing Takapsic̣api or ball play, often known as lacrosse, on Shakopee’s Prairie, the earlier location of Ṡakp̣e’s Village, the present-day site of the town of Shakopee. The Dakota played the game in contests between villages and with other tribes at meeting places.

Many years later the missionary Samuel Pond gave a more detailed account of Dakota ball play. He noted that “all the active and able-bodied men engaged in it,” though women also had their own form of the game that was played most often on frozen lakes and rivers. Men wore only breechcloths and moccasins, but they were highly decorated with body paint and ribbons or feathers, “which fluttered like streamers when they ran.” The game began when the ball was carried to the center of the ball grounds and tossed into the air, at which time “there was a general rush, followed by a clattering of clubs” by members of the two contesting teams, including, in all, a hundred or more players. The ball could only be touched with the club and the goal was to direct it across two opposite boundaries about a half mile apart, each representing one of the teams. While Pike suggested players could keep the ball “in the air for hours,” Pond stated that the net in the hoop of the ball club provided a most precarious surface in which to hold the ball, so that only the most adroit player could balance it there while running toward the goal line. The ball often fell on the ground, and players struggled to get it or direct it through the air as far as possible past the other players, who were scattered throughout the game grounds.70

The game required great dexterity, and because men collided, giving and receiving “accidental blows from ball clubs,” there were often injuries. The players’ endurance was tested, as were their tempers. The inhabitants of two or three villages might watch the game at the borders of the field, “elated or depressed as the ball went this way or that across the playground.” Players and spectators bet upon the game’s result, often, Pond stated, more than they could afford to pay. Spectators were loud in their applause or “sharp censure” about the course of the game and the actions of individual players.

The game paused after one of the teams scored a point but soon resumed, though unlike Pike, Pond was vague about just how it was determined that a game had ended. He noted, “The game might be soon decided by the defeat of one of the parties, but it was more likely to continue till all were glad to have it end and indeed needed several days of rest.”

In writing about Dakota ball play in the 1830s, Pond suggested it was a pure sport, one in which “religious ceremonies were not mingled,” and shared many picturesque qualities comparable to the games of ancient Greece. Though “nearly naked,” the players were “quite as well clothed as the competitors in the old Grecian games.” He noted “this would have been one of the most celebrated games in the world if it had been played by the ancient Greeks and described by Homer.”71

In later letters, however, Pond gave differing interpretations of the game, presenting the missionaries’ prevailing view that it was “heathen” in nature. In August 1835, early on in his residence at Lake Calhoun, Pond wrote about all the events occurring in the community on the Sabbath morning. A man came to borrow an ax, another was chopping wood outside his window, women and children were “screaming to drove the blackbirds from their corn.” Then “again I am interrupted by one who tells me that the Indians are going to play ball near our house to-day. Hundreds assemble on such occasions. What a congregation for a minister of Christ to preach to! Alas! As far as I know, the glad tidings of salvation never reached the ears of a Dakota. Yet I cannot hope that some will be gathered into the fold of Christ even from among this wild and savage nation.”72

Samuel Pond’s brother Gideon also wrote disparagingly of Dakota ball play and the contexts in which the Dakota played it. He noted that in 1845 the chief he called Mahkanartahkah, or Ground Kicker, “made a ball-play to the spirit of a child he lost last fall.” He bought “$50 or $60 worth of clothing and invited ninety men to play for it, forty-five on a side. Besides this he feasted them all.” Gideon Pond compared it to a card game called “game-of-the-departed-spirits,” whose object was conciliating the spirits of the dead. He suggested the Dakota believed beautiful weather was evidence of a favorable view. In the case of the ball play, he noted sarcastically that there had been an ensuing snowstorm. “Heathenism is expensive,” Gideon Pond wrote.73

Other missionaries abhorred the game because it involved gambling and was therefore viewed as a form of “dissipation” that prevented the Dakota from hearing their religious message. Though the missionaries’ accounts only vaguely suggested the social context in which games were played, the teams represented the villages from which they came, which meant the games were viewed as tests of the pride and strength of villages and their people. Lawrence Taliaferro, the Indian agent at Fort Snelling in the 1820s and 1830s, provides numerous examples of these contests. Although Taliaferro shared the missionaries’ perspective about the need to “civilize” the Dakota, he did not seem to view ball play as interfering with the mission. Instead, he appeared to appreciate it as a picturesque sport which he was eager to show off to visitors, both men and women. Taliaferro also found it useful to encourage ball play as a summer distraction that might prevent young men from going to war. In May 1829 sixty men of the Black Dog band participated in a “Grand Dance” at the council house and other locations. He gave them tobacco and rations of bread and pork, noting “The day was a fine one. This is the season for War & I keep all the Bands amused…either playing at Ball, Dancing or some feasting expectation.”74

In June 1834, two teams of a hundred men each played ball near the agency. The game was “well contested, with stakes including two horses, six guns, eight kettles, and six blankets.” Black Dog village was the winner, though Taliaferro did not state which team they were playing. The following year in July he received a visit from the artist George Catlin, who was touring the Upper Mississippi with his wife. Eager to provide picturesque subjects, Taliaferro arranged for members of Lake Calhoun’s Cloud Man village to dance and play ball for him. They assembled “painted and ready for play,” but the game was interrupted by a violent storm. Catlin gave them several loaves of bread, and they promised to reappear the next day. Taliaferro noted that “the Ladies were all expectation—but have unluckily been disappointed. I will try again to gratify and amuse them.” The next day, July 4, he reported that “the different villages of the Sioux played ball for the amusement” of the Catlins.75

Taliaferro also stated that Catlin took “the likeness of two Sioux at Ball Play in the act of doing so.” Catlin said that he painted the two men, “Ah-no-je-nahge [Anoka Inażiŋ] (he who stands on both sides), and W-chush-ta-doo-tah (the red man),” possibly both from Cloud Man’s village, exactly as they “had struggled in the play,” though they posed for him in his “painting room.” Catlin noted that the Dakota generally held the club with both hands, unlike the Choctaw, who from Catlin’s observation used two clubs. It was much more difficult, he stated, to catch the ball with the hoop of one club than to wedge it between two.76

Taliaferro recorded a number of occasions when Dakota played ball with Ojibwe people around Fort Snelling. In July 1835 Ojibwe who often came to the Indian agency at the fort to negotiate short-term treaties with the nearby Dakota danced at the fort and then at the Indian agency council house. The following day they were planning to play ball. Taliaferro wrote, “The Sioux stake Guns & Blankets—Chippeways stake—Bark Canoes, & Sugar.” These were the kinds of goods the two tribes generally traded with each other, since the Ojibwe were no longer within the agency’s jurisdiction at that time and so could not get the kinds of trade goods the Dakota did. For their part, the Dakota desired birch-bark canoes to use in harvesting wild rice. Later on that same year Taliaferro reported, via interpreter Scott Campbell, that the Dakota and Ojibwe were camped at the falls of the St. Croix River, dancing, playing ball, and feasting together. The Ojibwe had invited them to the area to hunt.77

According to Taliaferro, ball play could occur any time throughout the year, often associated with seasonal ceremonies. In February 1836, while the rivers were still frozen and there was snow on the ground, he noted that the Dakota had concluded their medicine ceremonies, ball plays, and other unnamed activities and were going to go on their spring hunts, which would continue into April.78

Taliaferro made no references to the Dakota women’s version of ball play, but several accounts and visual images exist. In 1835, when descending the Mississippi River from his visit to Fort Snelling, Catlin stopped at Prairie du Chien, where he observed a different kind of ball game played by the women of Wabasha’s village, which had come there to receive its annuity payments. The men hung a quantity of ribbons and calicoes from a pole to be stakes in the game. Two balls were attached to a string about a foot and a half long. Each woman had a short stick with which she tried to catch the string and throw the two balls across the goal. According to Catlin, the game was as fiercely contested as those played by men and could go on for hours. Catlin recorded the scene in a painting showing the rushing women at play and the men who cheered them on.79

Another portrayal of the women’s game was done by Seth Eastman, a military officer stationed at Fort Snelling in the early 1830s and again in the 1840s—an oil painting likely made during his later visit. It shows the women at play on a prairie, probably the area west of Fort Snelling. Eastman’s wife, Mary, described a women’s game, similar to Catlin’s account, in one of the stories in her book Dahcotah, or Life and Legends of the Sioux. She told of the women playing a game on the ice during December for the prize of “bright cloths and calicoes” hanging on a pole. However, the game involved the same kind of bat and ball used in the men’s version.80

Despite curiosity and even interest, it was hard for Europeans to fully grasp all the social and cultural contexts of Dakota ball play and its role in inter-village social relations. Anthropologist Ruth Landes, in interviews with Dakota people at Prairie Island in the 1930s, learned that during the summer months Red Wing villagers were invited to play ball and have other athletic contests with Kap’oża and a village at present-day Mendota. Games were usually played from May to August. Messengers were sent between the villages, a first to tell people to start to train, a second to name the date of the games, “a third to remind the villages of the name and place of the host village and urge all to attend.” Bets were put up in advance. According to one of her informants, rivalries between villages were sometimes expressed by the use of “gaming medicines” designed to disrupt opponents, though this more often was done during foot races.81

Historian Edward D. Neill wrote that “the last great-ball play” in the present-day Twin Cities area occurred on July 13, 1852, at Oak Grove in Hennepin County, the site to which Samuel and Gideon Pond and the Cloud Man’s village band had relocated in 1843. According to Neill, the parties were Ṡakp̣e’s band playing against the Good Road (Penichon), Sky Man (Cloud Man), and Gray Iron (Black Dog) bands. The game involved two hundred fifty players and lasted for several days “encompassed by a cloud of witnesses.” Ṡakp̣e’s band won the first day, receiving a prize of about two thousand dollars’ worth of property. During the next two days Ṡakp̣e’s band lost three games. Neill reported that a quarrel broke out about some of the prizes, and the Black Dog village band left just as a company from Kap’oża came to reinforce Ṡakp̣e’s. Throughout these several days, he said, four or five thousand dollars changed hands.82

Neill’s account made clear the nature of the social relations involved in the game, but with an undertone of sarcasm about the expense involved. However, once again the games’ full context was not given from the point of view of the people themselves. Ite Maza (Iron Face), whose English name was Jack Frazer, was a member of the Wakute or Red Wing band of Dakota in the 1820s and 1830s. His account communicated a sense of the excitement that attended Dakota communities gathering in the summer for such games. It told of one occasion when the three most easterly bands—those of Wabasha, Red Wing, and Little Crow—played against “all the other new comers: from other bands.” They were encamped near Sand Point at the midpoint of Lake Pepin, in the vicinity of present-day Lake City, and they continued to play for an entire month, with heavy bets of “horses, guns, kettles, silver works and other valuables.”83

A more detailed account from the Dakota point of view was written by Charles Eastman in his book Indian Boyhood, in which he told of a Dakota ball game that occurred when he was a small boy living in a Waḣpetuŋwaŋ village on the Minnesota River. Since Eastman was born in 1858, this event would have occurred after the removal of the various bands to the Upper Minnesota River. Sisituŋwaŋ, Waḣpetuŋwaŋ, and Bdewakaŋtuŋwaŋ bands were located in villages stretching from below Fort Ridgely to the Lower Sioux Agency and beyond, all the way to Lac qui Parle.84

Eastman wrote that the events took place at midsummer, after fur hunters had been successful in the spring and the maple harvest had been productive. The women’s gardens were already producing corn and potatoes. There was plenty of stored wild rice and dried venison from the winter, as well as “freshly dug turnips, ripe berries, and an abundance of fresh meat.” Suggesting the context of the period following the Treaty of 1851, he wrote, “The Waḣpetunwan band of Sioux, the ‘Dwellers among the Leaves,’ were fully awakened to the fact that it was almost time for the midsummer festivities of the old, wild days.” The planned event, he wrote, was something like a present-day midwestern state fair for the Dakota. Invitations in the form of tobacco were sent to the various bands, including the “Light Lodges,” or Kap’oża band, the “Dwellers Back from the River,” or Cloud Man band, and others from the Blue Earth (Makato) band, a Waḣpetunwan group located close to the Lower Agency.

When the various bands gathered, Makato’s tepee was “pitched in a conspicuous spot, with a picture of a pipe painted above the entrance and opposite, the rising sun, symbolic of welcome and good will to men under the bright sun.” There was a meeting to appoint a “medicine man” or spiritual leader to make the balls used in the contest. The task was given to “Chakpee-yuhah, Keeps the Club,” who one evening appeared in the circle of tepees to dedicate, in a sense, the coming games. He brought with him a little boy who wore “a bit of swan’s down in each ear,” referring to the kind of decoration other accounts mention being worn by ball players. Though Eastman wrote the story in the third person, it is evident that the young man was himself. Chakpee-yuhah announced that the game would be between the Kap’oża band—whom, he said, addressing that band, “claim that no one has a lighter foot than you”—and the Waḣpetuŋwaŋs. He brought two balls, a black one representing the Kap’oża band and a red ball for the Waḣpetuŋwaŋs. He announced that if the Waḣpetuŋwaŋs won the game, the young man (Eastman himself), who until now had borne the name Hakadah, which he implied meant “the pitiful last,” would then be known as “Ohiyesa, or Winner.” If the Kap’oża band won, one of their children could receive the name.85

The ground for the game was a narrow strip of land between a lake and the Minnesota River, three-quarters of a mile long and a quarter of a mile in width. Given the general location, the lake could have been an oxbow or backwater of the river. Spectators were arranged along the sides and ends of the grounds. “Soldiers,” essentially village policemen on horseback, had the job of keeping order. Eastman noted that “they were so strict in enforcing the laws that no one could venture with safety within a few feet of the limits of the field.” Order also required that “if any one bore a grudge against another, he was implored to forget his ill-feeling until the contest be over.”

Like outside observers, Eastman described the impressive body paint worn by the players, including images of the rainbow, the sunset sky, the Milky Way, lightning, and “some fleet animal or swift bird.” Players were arranged strategically, “as in a basketball game,” with the largest men in the middle to receive the ball when it was thrown up in the air at the beginning of the game. Eastman details the precariousness of the racket in holding the ball and the desperate shots across the field, with players clashing to reach it. Though one team or another seemed to get the advantage, the game reached a point when “the herald proclaimed that it was time to change the ball.” After a few minutes’ rest the red ball was tossed into the game, leading to the resumption of battle, with more than a hundred men scrambling for it. Eventually, a player named Antelope took the sphere and began to run for the goal. Interestingly, Eastman describes the ball being nestled in his palm and him throwing it. It is unclear how this maneuver would have been possible under the rules as described by other accounts, although perhaps there was some provision for it. Despite the valiant efforts of several of the opposing Kap’oża band, Antelope was able to get the ball across the goal. As a result, Eastman received his name, Ohiyesa, at an assembly in which Makato spoke graciously about the opposing Kap’oża band, in the “friendly contest in which each band must assert its prowess.”

Given Eastman’s age at these events, it is unclear how many details he remembered and how many were based on the stories he heard as he was growing up. In any case, he was able to place ball play in a context far richer and more in keeping with Dakota cultural traditions and values than the accounts of missionaries and other European Americans. For the Dakota, the ball game encapsulated community history and identity and multiple strands of their values and their culture. In telling this story many years later, Eastman described the last days of the Dakota in their homelands of Mni Sota Makoce, before the beginning of their exile.

A TOUR OF DAKOTA SUMMER VILLAGES

In the nineteenth century Dakota summer villages spread across present-day south and central Minnesota from west to east, along the Minnesota and Mississippi rivers from Lake Traverse and Big Stone Lake and through the Twin Cities area to the far southeastern corner of Minnesota. These villages were the base of operations where Dakota communities grew their summer crops and from where they set out for other activities away from the rivers at various times of year.

LAKE TRAVERSE, BIG STONE LAKE, AND LAC QUI PARLE