1

RETHINKING THE MISSION OF THE MEDICAL SCHOOL

Trevor Gibbs

Increasing attention is being focused on the social responsibility and accountability of a medical school internationally and in relation to the community for which they serve.

Michel Montaigne, a well-respected educationalist of his time, reflected that for many years we have worried over the state of education of our students and battled with the dichotomy that exists between didactic teaching and efficient learning.

(Michel Montaigne (1533–1592), French Renaissance philosopher)

Almost 400 years later, the Flexner Report (Flexner 1910) criticised the lack of scientific teaching in North American and Canadian medical schools, as well as questioning the didactic approach to medical education. As a result, we hope that our approach to student learning has changed for the better.

Although the Flexner Report (Flexner 1910) is more remembered for its success in creating a single and hopefully more efficient model of medical education, we should also note that it resulted in the closure of approximately half of the medical schools in America – perhaps a success for medical education in general but a travesty for many individual schools. As a result of the report, medical education became much more expensive, and by closing those schools that admitted African-Americans, women and students of limited financial means, it placed many appropriate students out of reach of graduating in medicine; schools became better but more elitist. That itself raised an important question: what is the relationship between a medical school and the community its graduates serve?

There is little doubt that the dynamic of the last century of medical education has seen a change of emphasis from process (how to educate) to product (the graduate) and, more latterly, to create a careful balance between the two to produce a ‘fit for practice’ graduate. More than a century after the seminal Flexner Report, the main challenge for health professions’ educators is now to create medical and healthcare educational institutions that are responsible for graduating future healthcare professionals, who will be the change agents of the future (Global Consensus for Social Accountability of Medical Schools (GCSA) 2010).

Over the last three decades a variety of innovative educational interventions are deemed to have created ‘better’ doctors, with the implication that these doctors mean better healthcare. According to the American Board of Internal Medicine Foundation (2002), these doctors should be graduates who not only excel as excellent care providers, but also support patients’ autonomy and are advocates of social justice; they are socially and community-aware.

Hence, as we move into an era where we pay as much attention to the product as we do the process, we find that we are paying increasing attention to what is described as the social accountability of a medical school – the obligation of schools to direct their education, research and service activities towards addressing the priority health concerns of the community, region and nation they have the mandate to serve (Boelen and Heck 1995). But what does social accountability mean, how should it be interpreted and acted upon by medical schools and, most importantly, how can its effectiveness be assessed?

By describing the concept of social accountability in greater detail and illustrating it with five case studies, each drawn from various parts of the globe, and schools at different stages of social accountability development, this chapter will attempt to answer those important questions.

Why social accountability?

Perhaps before addressing the question of what is social accountability, we should address an equally important question: why social accountability? In 2010, Frenk and colleagues, in referring to The Independent Global Commission on Education of Health Professionals for the 21st Century, suggested that the education of medical students should match the changing health system needs (Frenk et al. 2010). They suggested that medical school graduates’ qualities must match the competencies and attitudes required to ensure they are able to solve priority health needs (Sen Gupta et al. 2009; Sales and Schlaff 2010), as well as developing the leadership skills that enable them to be ‘enlightened change agents’ of the future (Frenk et al. 2010). This thought or proposal is clearly seen in the case studies from Tunisia, Australia and Canada, which prompted change to ‘reorienting their curriculum to the priority healthcare needs of their country’.

At the same time other authors were asking that we address the global shortage, medical migration and uneven distribution of healthcare workers and create curricula that better prepare graduates who are fit for purpose for the community (or communities) they are going to serve (Strasser and Neusy 2010; World Health Organization 2010; Gibbs and McLean 2011). This is clearly illustrated in the case study from the Ateneo de Zamboanga University-School of Medicine, Philippines, in which there was a large part of the country’s population not served by any medical school or efficient healthcare provision.

Case study 1.1 The new mission of the Faculty of Medicine of Tunis, Tunisia, Africa

Ahmed Maherzi

The Faculty of Medicine of Tunis (FMT) had always been committed to train doctors with the triple mission of education, research and care, but had not verified the impact of its actions on Tunisian society (Boelen 2012). An internal assessment in 2002 and an external assessment by the Review Board of the International Conference of Deans of French-speaking Medical Schools in 2005 (CIDMEF 2006) pointed out deficiencies of the educational system: the choice of general practice as a career was made by default, usually resulting from students failing to be admitted for other specialty training; the clerkship training was mainly hospital-based teaching, with an emphasis on the specialties; research was not given its proper recognition; there was limited interaction with the poorest areas of the country; and there was a clear lack of independent assessment and performance procedures.

Subsequently, the FMT made it a priority to enhance family medicine by reorienting the curriculum towards the priority health needs of the country: to improve bedside training, to enhance clinical research, to set up an assessment department and develop a partnership strategy with regional hospitals.

A first step was to reform medical education at national level, promoting family medicine (JORT 2011) in the four Tunisian medical schools, and providing students with common core training in primary care which reflected the major health problems of the population.

To improve quality and equity for people living in most disadvantaged areas, the FMT initiated a partnership with several regional hospitals in north-western parts of the country. This project had several objectives: to coordinate and improve first, second and third levels of healthcare delivery; to support continuing medical education of local health professionals; and to organise formal collaborative ventures between the FMT with local medical and paramedical teams in order to improve professional competences. The medium-term goal was to establish, through a collaborative approach, centres for mother and child health, emergencies and medical specialties such as psychiatry and oncology. A working group including national and international experts is currently being formed to evaluate the initiative through specific indicators (Boelen 2012).

This new vision of social accountability has changed the training strategy of the school, and using the GCSAMS (2010) document has also initiated a national interest for improving quality through accreditation procedures. This endeavour has also been conducted in consultation with an international group of experts to ensure that the performance of Tunisian medical schools meets the best standards in education, research and service delivery for the well-being of its citizens.

Case study 1.2 James Cook University School of Medicine, Australia

Sarah Larkins, Richard Murray, Tarun Sen Gupta, Simone Ross and Robyn Preston

The James Cook University School of Medicine (JCU-SOM) (now the College of Medicine and Dentistry) was established in 2000 as the first new Australian medical school in over 20 years and the only school in the northern half of Australia. Northern Australia’s population is dispersed over a huge geographical area, with no settlement larger than 200,000 people, and suffers from a maldistribution of health professionals. For example, in 2012, the ratio of doctors to population varied from one medical practitioner for every 246 people in major cities, to 1:425 in outer regional and remote areas (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare 2014b). Health status is in inverse proportion to this (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare 2014a).

The JCU-SOM originated with a clear mission to train doctors to respond to the health needs of rural, remote, Aboriginal, Torres Strait Islander and tropical populations, and with articulated values of social justice, excellence and innovation.

The JCU-SOM’s social mission is to address the priority health needs of underserved populations using an approach aligning the selection of medical students, curriculum and clinical placements to the health and healthcare needs of northern Australia. This role should extend beyond graduation, in particular through partnering with the health sector to create appropriate postgraduate training pathways to meet the needs of the region. The selection process favours students from rural origins and Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people. The students are exposed to early and substantial rural clinical placements studying a curriculum with a strong focus on primary care and rural, remote and tropical health issues in these geographical areas. The staffing profile, research activity, professional interests and advocacy of the school reflect these priorities. The school partners with the health sector to develop rural hospitals and practices as teaching health systems, and has been instrumental in developing postgraduate training pathways in rural generalist medicine. Likewise, research activities focus on health service strengthening, health workforce training and optimising the accessibility of health services for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander, rural and remote and other medically underserved populations (Figure 1.1).

The school also partners through the Training for Health Equity Network (THEnet) (www.thenetcommunity.org), with participating schools throughout the world. THEnet partners have developed, piloted and published an evaluation framework to measure progress towards socially accountable health professional education in real-world health professional school settings across contexts (Larkins et al. 2013). With its THEnet partners the school has implemented an international Graduate Outcome Study, following students at all 11 schools from entry to medical school, to graduation and for 10 years thereafter in terms of their origin, their practice intentions, actual practice destination (geographical and specialty) and attitudes to serving underserved groups.

The JCU model of medical education has been a success, with 65 per cent of graduates spending their first postgraduate year in non-metropolitan locations and this pattern continues in later postgraduate years (Sen Gupta et al. 2014). Around half of the graduates are undertaking generalist specialty training (general practice or rural medicine), considerably more than from most Australian universities, and they are already making a clear contribution to the northern medical workforce.

Case study 1.3 Northern Ontario School of Medicine, Canada

Roger Strasser

Northern Ontario is geographically vast, with a volatile resource-based economy, and 40 per cent of the population living in rural/remote areas and diverse cultural groups, most notably Aboriginal and francophone peoples. The health status in Northern Ontario is worse than in Canada as a whole and there is a chronic shortage of health professionals (Rural and Northern Health Care Panel 2010; Glazier et al. 2011). In 2001, the Ontario Government established the Northern Ontario School of Medicine (NOSM) with a social accountability mandate to contribute to improving people’s health. NOSM is a joint initiative of Laurentian University, Sudbury (population 160,000) and Lakehead University, Thunder Bay (population 110,000). The university campuses are over 1,000 km apart and provide teaching, research and administrative bases for NOSM, which is a rural-distributed community-engaged school (Tesson et al. 2009).

Uniquely developed through a community consultative process, the holistic, cohesive MD programme curriculum is grounded in the Northern Ontario health context. The curriculum is organised around five themes: ‘northern and rural health’, ‘personal and professional aspects of medical practice’, ‘social and population health’, ‘foundations of medicine’ and ‘clinical skills in healthcare’ (Strasser et al. 2009) and it relies heavily on electronic communications and community partnerships to support distributed community-engaged learning (DCEL). In classrooms and in clinical settings, students explore cases from the perspectives of physicians practising in Northern Ontario. There is a strong emphasis on interprofessional education and integrated clinical learning, which takes place in over 90 communities and multiple health service settings, so that the students gain personal experience of the diversity of the region’s communities and cultures (Strasser et al. 2009; Strasser 2010; Strasser and Neusy 2010).

NOSM was the first medical school in the world in which all students undertake a longitudinal integrated clerkship, the Comprehensive Community Clerkship (CCC) (Couper et al. 2011; Strasser and Hirsh 2011). During the year, students achieve learning objectives which cover the same six core clinical disciplines as in the traditional clerkships and live in one of 15 communities.

NOSM graduates have achieved above-average scores in national examinations, including top-ranking scores in the clinical decision-making and patient interaction sections. Most students chose family practice (predominantly rural). Almost all other MD graduates (94 per cent) are training in family medicine and other general specialties, with only 6 per cent training in subspecialties. A growing number of NOSM graduates are practising family physicians in Northern Ontario and have become NOSM faculty members. The socio-economic impact of NOSM includes: new economic activity, more than double the school’s budget; enhanced retention and recruitment for universities and hospitals/health services; and a sense of empowerment among community participants, attributable in large part to NOSM (Strasser et al. 2013).

Implementing DCEL is challenging. The first challenge is to counter the conventional wisdom that universities are ivory towers separated from ‘real-world’ communities. Persuading community members that the medical school is serious about meaningful partnerships requires considerable discussion. Successful DCEL depends on empowering communities to be genuine contributors to all aspects of the school. This includes local health professionals who are full clinical faculty members. The partnerships are facilitated by formal collaboration agreements which set out the roles and functions of the partners, including the local steering committee, which provides the mechanism by which the school is a part of the community and the community is a part of the school.

Case study 1.4 The Ateneo de Zamboanga University-School of Medicine (ADZU-SOM), Philippines

Fortunato L. Cristobal

Zamboanga Sulu Archipelago is one of the most marginalised and medically underserved regions in the Philippines. Almost four million people live in its mountainous rural and island municipalities, with their lives punctuated by sporadic political unrest. Only 300 doctors served this region in the early 1990s and the nearest medical school is 600 km away. Frustrated by poor community health status and ongoing doctor shortages, a group of local doctors developed a non-profit medical school foundation to address the region’s priority health needs; the Zamboanga Medical School Foundation was established to pioneer and implement an innovative health development and social equity-focused medical curriculum with the expressed purpose of providing solutions to the health problems of the communities in the region.

By 1993 professional development seminars had started to develop new teaching pedagogies and innovative curricular ideas about social and community models for illness and health development. The first students entered in 1994 and a spirit of institutional and individual volunteerism has existed since; faculty are paid a very modest honorarium dependent upon their responsibilities. A local private university initially contributed free teaching space and civic leaders raised local and international scholarships to keep student fees affordable. Students were purposely recruited from the region.

The five-year MD curriculum has the Philippines’ most pressing national and regional health priorities at its core. All basic sciences, clinical content and social/community models for health are integrated within a longitudinal problem-based learning (PBL) approach; health development, social determinants of health and the social justice underpinnings for addressing health inequalities are highlighted. A community-based practicum begins in the first year and ends with students living and practising in small communities for the entire fourth year. Three-quarters of all clinical attachments are in remote rural communities, with only a quarter being hospital-based.

As a result of this social approach, the students’ projects have included building community pit latrines; improving potable water access; developing solid-waste management policies; increasing immunisation rates in children; determining risk factors for tuberculosis directly observed therapy (TB DOTS)-defaulting patients; developing cottage industry-based income generation schemes; and creating home vegetable gardens to augment local food resources. Mobilisation of effective community health volunteers has improved the early detection of asymptomatic hypertension, adult diabetic patients and malnourished children.

Understandably, the changes were met with initial scepticism, with doubts cast about the quality of its graduating doctors. However, the results from the school speak loudly for themselves: to date, 220 students have graduated with an MD, more than 50 per cent with a combined MD/MPH degree; 200 have passed the Philippine National Medical Board examination, with a pass rate of 95.23 per cent, which is higher than the majority of Filipino schools with traditional curriculum and teaching methods. Over 97 per cent of the graduates are presently still practising in the Philippines. Seventy-five per cent of the graduates still practise within the region of the medical school, with 50 per cent based in rural and remote areas.

Developing an innovative medical school in pursuit of a social goal was a challenging and daunting project for all. However, social justice demands that the pressing, unfulfilled health needs of our marginalised communities receive our energetic collaboration, with all sectors contributing to this end; the volunteers at Zamboanga have shown a way forward for even the poorest of regions to assert that historic disadvantage does not have to be an ongoing destiny.

Case study 1.5 Lessons from eight medical schools in South Africa – the CHEER collaboration

Stephen Reid

The Collaboration for Health Equity through Education and Research (CHEER) was formed in 2003 to examine strategies that would increase the proportion of health professional graduates who choose to practise in rural and underserved areas in South Africa. Consisting of eight individuals – one from each of the universities in South Africa with a medical school plus one member from a health science faculty without a medical school – they undertook a literature review (Grobler et al. 2009), a qualitative study (Couper et al. 2007) and a case-control quantitative study (Reid et al. 2011) to address the original research question: how to increase the number of health professionals in rural Africa? Three series of peer reviews at each university addressing key issues of collective concern formed an integral process in the collaboration (Table 1.1).

The first round of peer reviews (Reid and Cakwe 2011), assessed each faculty in terms of 11 themes which would contribute to the preparation of graduates for service in rural and underserved areas (Table 1.2). The gap between the stated intention of the faculties and their graduate outcomes was clearly demonstrated, except in the area of technical clinical skills. There were noteworthy exceptions, however: at one faculty, for example, community members contribute not only to the recruitment and selection of medical students, but also to curriculum development and student assessment at community sites.

The second round of peer reviews tackled the issue of the relationships between universities and their health service partners. A scale was devised from formal ‘transactional’ relationships on the one hand, often circumscribed by legal memoranda of understanding, to less formal ‘communal’ relationships on the other hand. Central and tertiary hospitals tended towards the former, whereas the relationships at community health centres and other community-based sites were more informal. A consistent challenge that many programmes faced was balancing the need to provide health services to large numbers of patients in under-resourced situations with the simultaneous need to provide quality medical education and supervision of clinical placements for students.

Table 1.1 CHEER peer reviews – research questions

| Phase 1 |

2005–2008 |

How do health sciences faculties prepare their graduates for working in rural and underserved areas in South Africa? |

| Phase 2 |

2008–2012 |

What is the nature of the relationship between health science faculties and their health service partners? |

| Phase 3 |

2012– |

What are the nature and extent of social accountability of health sciences faculties in South Africa? |

Table 1.2 Themes used for peer review assessments of the preparation of graduates for practice in rural and underserved areas

1 Faculty mission statements

2 Resource allocation

3 Student selection

4 First exposure of students to rural and underserved areas

5 Length of exposure

6 Practical experience

7 Theoretical input

8 Involvement in the communit

9 Relationship with the health service

10 Assessment of students

11 Research and programme evaluation

Finally, a third round of peer reviews aimed to measure the social accountability of medical schools, using an adaptation of THEnet Social Accountability Framework (Training for Health Equity Network 2011) based on the ‘CPU model’ (Boelen et al. 2012; see below for further explanation).

There is a major disjuncture between health sciences education and health service needs in South Africa, both in terms of the numbers and the career choices of graduates, as well as the curative and specialist orientation of their skills. A fundamental realignment to South African context is needed, and the CHEER peer review and research project collaborations have been able to highlight and quantify the important gaps.

As a group of peers inclusive of every medical school in the country, a common purpose developed in supporting one another to find better ways of making our medical graduates more ‘fit for purpose’ in terms of the health needs of the country. Overall, the collaboration stimulated a number of successful collaborative research projects which contributed to national policy development as well as accreditation practices. In addition, the peer review approach was highly successful in sharing common challenges, spreading innovative practices and stimulating new ideas. In our experience with CHEER, ‘what works’ is comprehensive collaboration and peer support, in trying to find the best ways to tackle very complex issues in under-resourced circumstances in South Africa.

According to Boelen and Woollard:

(Boelen and Woollard 2011: 614)

But how do medical schools organise themselves to address these challenges, specifically through their education, research and service delivery functions? In part these questions are answered by the South African case study, in which a group of medical schools organised themselves into an effective group with the same mission; making their graduates ‘fit for purpose’ for the whole country.

What is social accountability?

The World Health Organization (WHO) defines social accountability in medical schools as:

(Boelen and Heck 1995: 3)

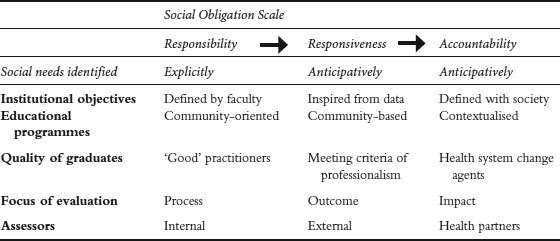

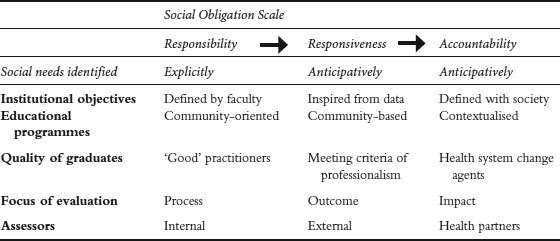

Over the years social accountability has come to represent the ultimate in a spectrum of educational responses to social need. However, two other intrinsically related aspects of the spectrum, social responsibility and social responsiveness, have become apparent and need further explanation.

The term social responsibility simply implies an awareness of a school’s duties towards learning from the community and society. An example of this would be for a school to run a course in public health or primary care, but have little or no purposeful engagement with or within the community. A socially responsive school takes this further and engages its students in community-based learning activities throughout the curriculum, creates educational outcomes related to the community and society, assesses these and hopefully encourages graduate students to practise within that community. In a socially accountable school, the school creates an even closer affiliation with its community; discusses health priority needs with its community to shape the curriculum; creates curricular programmes to respond to these needs; verifies whether anticipated outcomes and results have been attained in satisfying social needs; and bases their commitment to research and service delivery functions upon these needs.

This spectrum of socially oriented education can be further explained by referring to the Social Obligation Scale described by Boelen et al. (2012) (Table 1.3). As discussed by Boelen, the three concepts are not specifically distinct and flow from one to another through an incremental process, eventually focusing on a desired level of achievement or outcome. The social needs serve as references, whether implicitly in the case of responsibility, or explicitly in the case of responsiveness, or anticipatively, through collaboration, investigation and research, in the case of accountability. Social accountability asks that a medical school acts proactively to foresee its place in the development of medical graduates who will eventually fulfil a declared and dynamic social obligation. This important principle is seen in all five case studies, with each school recognising a need to shape its graduates to be able to fulfil the future needs of their region or country.

Once medical schools have agreed that they wish to move on from the levels of social responsibility and social responsiveness and accept the principles of social accountability, they need to change definitional descriptors into activities – translate the concept into actions. Using the WHO definition of social accountability (Boelen and Heck 1995), the activities required of the institution can be divided into four distinct groups: organisational management, educational policy, research and collaboration with community agencies and service providers.

Table 1.3 The Social Obligation Scale (modified from Boelen et al. 2012)

At this point readers may wish to re-read the five case studies within this chapter, so that they can match the actions/activities described below with how the schools in the studies implemented the concept of social accountability.

Organisational management

Social accountability should be a prime directive in a medical school’s purpose and mandate and integrated in its day-to-day management. This would imply that:

• the subject of social accountability becomes a priority in the medical school’s mission statement and strategic plans;

• through discussion with its local, region and national contacts, the school uses the information gained to shape its vision and mission in all the areas of education, research and service delivery;

• the school’s contacts for active engagement and consultations are drawn from all levels of its community and health system organisation.

In the JCU-SOM case study, the school started with a clear mission to train the doctors to be responsive to the health needs of its community. This was clear from its mission statement, which also articulated with the school’s values of social justice, excellence and innovation; social accountability permeated throughout the school, so that their staffing profiles, research activities, professional interests and advocacy matched and reflected this mission. In the FMT case study, the school specifically worked with its community and patient associations, while the NOSM case study made formal collaborative agreements with the community, the school becoming part of the community, and the community part of the school.

Educational policy

Admissions

Where possible a medical school’s graduates should reflect the demographics of the population served, which means that a school should attempt to recruit, select and support medical students who reflect the social, cultural, economic and geographic diversity of the community served, which in turn may mean recruiting from disadvantaged and under-represented areas. The hope is that those students are more likely to commit to future work within the school’s immediate community and region. The JCU-SOM specifically targeted potential students from rural and Aboriginal backgrounds and cultures, while ADZU-SOM successfully created scholarships to help local students from poor backgrounds.

Education programmes

To match the concept of social accountability, a school’s educational curriculum must create opportunity for students to learn from, participate in and work with the communities within which the school resides, whether at a local, regional or national level. Thus medical students are offered early and longitudinal exposure to community-based and community-oriented learning experiences to understand and act on health determinants and gain appropriate community clinical skills; the concept of professionalism, ethics, teamwork, cultural competence and leadership features highly in the curriculum, together with interprofessional learning and communication skills. In all of the five case studies, it is clear that a major part of their curriculum lies within the community, not simply placing students within that community, but encouraging learning activities that put as much back into the community as they take out.

In a medical school’s curriculum, the concept of social accountability should feature through core structured activities and voluntary elective periods, link programmes and cultural exchanges. Specific attention must be given to key health problems found in the community, and the students should have opportunities to learn within underserved and disadvantaged communities and populations, either through structured teaching and learning opportunities or by student-led projects designed to improve the health and healthcare of local, underserved and disadvantaged communities. The students in the ADZU-SOM case study created multiple developmental opportunities for their community.

Faculty development, continuing medical education and professional development

The aim of a medical school should be to promote lifelong learning in its faculty, which should be shaped and driven by the needs of the community and underpinned by an awareness of social accountability. Hence, faculty development programmes should focus on developing teachers who are socially aware and shape their teaching around social accountability; the same rules apply to continuing medical and professional development. Inherent within all of the case studies, but clearly demonstrated in the JCU-SOM, ADZU-SOM and NOSM, is the effect that a socially accountable curriculum has on the faculty. In each case, there has been an ability to retain faculty within the area of most need, and to retain a high grade of practitioners ready to facilitate student learning within the community.

Research

Research activities

In order that a medical school can be considered as socially accountable, it is important that the community, regional and national needs from research inspire and formulate the medical school’s research, including knowledge translation. Hence, dominant and prevalent patterns of disease and eradication of local or regional illnesses should take priority in research programmes. To do this a medical school should actively engage with and partner the community in developing their research agenda. Research from the school should be measured by its impact upon the community which the school serves.

However, a careful balance needs to exist that allows the school to benefit from available research monies from providers divorced from the community; much research is not related directly to community need since important community issues are not always seen as innovative areas for research. However, all five of our case studies have implied that their research is directed to the community needs; their community will benefit from their research activities. In these early days of social accountability, research results are not yet forthcoming, but building into the remit of the school the need to tailor research towards the needs of the local community suggests that it will not be long before this very specific activity bears fruit.

Collaboration with community agencies and service providers

A medical school’s graduates and its health service partnerships should have a positive impact on the healthcare and the health of its community. Inevitably this means that the school should form effective collaborative partnerships with other community stakeholders, including other health professional and governing bodies, to optimise its performance in meeting the requirement for the quality and quantity of trained graduates. A school’s postgraduate training programmes should be targeted towards producing a variety of generalists and specialists, appropriate both in quality and quantity to serve the medical school’s community, and towards the creation of ‘change leaders’, active in population health and health-related reforms, with an emphasis on coordinated person-centred care, health promotion, risk and disease prevention and rehabilitation for patients and communities. A medical school should work in partnership with potential employers of graduates to enable them to provide care in under-resourced specialties and to underserved and disadvantaged communities. In all of the case studies, active, effective partnerships were formed with their community. In the FMT case study, the healthcare providers were the local hospitals, specifically in socially deprived areas. JCU-SOM and ADZU-SOM chose to partner more rural hospitals and community teaching centres, while at NOSM a more rural and socially deprived community became an active partner of the medical school. In South Africa the CHEER partnership has been one of collaborative medical schools working together to improve the healthcare of their country.

Assessing the effectiveness of a socially accountable medical school

If medical schools are responsible for producing graduates with competencies and attitudes to address health inequities and respond to priority health needs, there needs to be a way of demonstrating that they have achieved their goal. At the present time there is one set of principles that can be applied to the assessment of a socially accountable medical school and one validated framework of assessment based upon those principles. In 2009, Boelen and Woollard described a set of three expressions of social accountability; they introduced what is now known as the CPU model. This has subsequently been placed into a framework and validated by a number of international medical schools that have critically evaluated the progress of their schools towards social accountability using the THEnet Evaluation Framework (Palsdottir and Neusy 2010; Larkins et al. 2013; Ross et al. 2014). Recently the CPU has been described, in greater detail and with more descriptors, by Boelen et al. (2012), in order to aid accreditation of medical schools that wish to express their ability to be a socially accountable school.

The CPU framework focuses on three ‘expressions of social accountability’:

1 C – conceptualisation; what sort of graduate the school needs to produce;

2 P – production; the type of teaching, learning and assessment methods used;

3 U – usability; the methods that are used to investigate the effectiveness of the graduates in providing the required service.

Extensive examples of each of the three expressions are beyond the scope of this short chapter. However, readers who are interested in a more detailed approach to the CPU model are recommended to read the paper by Boelen and colleagues (2012).

The full effect of a socially accountable curriculum has yet to be demonstrated, but early results suggest that the concept at least is meaning that more students are staying in the area of their medical school to practise (see JCU-SOM, ADZU-SOM and NOSM case studies).

Conclusion

If effective healthcare is related to the standard of training of doctors, then it appears logical that the training should also be related to the specific needs of the community, region or nation those doctors will eventually serve, rather than towards a more generic graduate whose skills may not be used to maximum effect. The concept of social accountability focuses on these specific needs and forms a framework for the medical school to work within to produce that graduate. It also extends the principles further into the areas of postgraduate education, continuing professional development, research and service delivery. When the CPU model is applied to social accountability it can assist in designing indicators that can help medical schools build their own benchmarks to assess progress towards accreditation in the area of social accountability and within the context of their particular environment.

Take-home messages

• Medical education has changed its emphasis from the process (how to educate) to the product (the graduate) and, more latterly, to a careful balance created between the two in order to create a ‘fit for practice’ graduate.

• Today’s medical schools and their educational programmes need to address priority health problems, anticipating the health and human resource needs of their community and ensuring that graduates are employed where they are most needed.

• Medical schools need to be socially accountable, to recognise their obligation to direct their education, research and service activities towards addressing the priority health concerns of the community, region and nation they have the mandate to serve.

• To match the concept of social accountability, the school’s educational curriculum must create opportunity for students to learn from, participate in and work with the communities within which the school resides, whether at a local, regional or national level.

• The medical school’s graduates and its health service partnerships should have a positive impact on the healthcare and the health of its community.

• If medical schools are responsible for producing graduates with competencies and attitudes to address health inequities and respond to priority health needs, there needs to be an effective way of demonstrating that they have achieved their goal.

Bibliography

American Board of Internal Medicine Foundation, American College of Physicians Foundation, European Federation of Internal Medicine (2002) ‘Medical professionalism in the new millennium: A physician charter’, Annals of Internal Medicine, 163(3): 243–6.

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (2014a) Australia’s health 2014. Australia’s health series no. 14, Canberra: AIHW.

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (2014b) Medical workforce 2012. National health workforce series no. 8, Canberra: AIHW.

Boelen, C. (2012) ‘Making an academic institution more socially accountable: The case of a medical school’, Presse Médicale, 41(12): 1165–7.

Boelen, C. and Heck, J. (1995) Defining and measuring the social accountability of medical schools, Geneva: World Health Organization.

Boelen, C. and Woollard, R. (2009) ‘The CPU model: Conceptualisation–production–usability’, Medical Education, 43(9): 887–94.

Boelen, C. and Woollard, R. (2011) ‘Social accountability: The extra leap to excellence for educational institutions’, Medical Teacher, 33(8): 614–19.

Boelen, C., Dharamsi, S. and Gibbs, T. (2012) ‘The social accountability of medical schools and its indicators’, Education for Health, 25(3): 180–94.

CIDMEF (Conférence Internationale des Doyens des Facultés de Médecine d’Expression Française) (2006) Politique et méthodologie d’évaluation des facultés de médecine et des programmes d’études médicales. Online. Available HTTP: http://www.cidmef.u-bordeaux2.fr/sites/cidmef/files/st_ev03_v2.pdf (accessed June 2013).

Couper, I.D., Hugo, J.F.M., Conradie, H. and Mfenyana, K., Members of the Collaboration for Health Equity through Education and Research (CHEER) (2007) ‘Influences on the choice of health professionals to practise in rural areas’, South African Medical Journal, 97(11): 1082–6.

Couper, I., Worley, P. and Strasser, R. (2011) ‘Rural longitudinal integrated clerkships: Lessons from two programs on different continents’. Rural and Remote Health, 11: 1665. Online. Available HTTP: www.rrh.org.au (accessed June 2013).

Flexner, A. (1910) Medical education in the United States and Canada: A report to the Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching, bulletin no. 4, New York City: The Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching.

Frenk, J., Chen, L., Bhutta, Z., Cohen, J., Crisp, N., Evans, T., Fineberg, H., Garcia, P., Ke, Y., Kelley, P., Kistnasamy, B., Meleis, A., Naylor, D., Pablos-Mendez, A., Reddy, S., Scrimshaw, S., Sepulveda, J., Serwadda, D. and Zurayk, H. (2010) ‘Health professionals for a new century: Transforming education to strengthen health systems in an interdependent world’, Lancet, 376(9756): 1923–58.

Gibbs, T. and McLean, M. (2011) ‘Creating equal opportunities: The social accountability of medical education’, Medical Teacher, 33(8): 620–5.

Glazier, R.H., Gozdyra, P. and Yeritsyan, N. (2011) Geographic access to primary care and hospital services for rural and northern communities: Report to the Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care, Toronto: Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences (ICES).

Global Consensus for Social Accountability of Medical Schools (2010) Consensus document. Online. Available HTTP: http://healthsocialaccountability.sites.olt.ubc.ca/files/2011/06/11-06-07-GCSA-English-pdf-style.pdf (accessed June 2013).

Grobler, L., Marais, B.J., Mabunda, S., Marindi, P., Reuter, H. and Volmink, J. (2009) ‘Interventions for increasing the proportion of health professionals practising in rural and other underserved areas’, Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, Issue 1.

JORT (Journal Officiel de la République Tunisienne) (2011) Décret N°90 du 25 novembre 2011 fixant le cadre général des études médicales, habilitant à l’exercice de la médecine de famille et à la spécialisation en medicine. Online. Available HTTP: http://www.ordre-medecins.org.tn/pdf/bulletin-2013-def.pdf (accessed 23 March 2015).

Larkins, S.L., Preston, R., Matte, M.C., Lindemann, I.C., Samson, R., Tandinco, F.D., Buso, D., Ross, S.J., Palsdottir, B. and Neusy, A.J. (2013) ‘Measuring social accountability in health professional education: Development and international pilot testing of an evaluation framework’, Medical Teacher, 35(1): 32–45.

Palsdottir, B. and Neusy, A.J. (2010) Transforming medical education: Lessons learned from THEnet. Commission Paper June 2010.

Reid, S.J. and Cakwe, M. on behalf of the Collaboration for Health Equity through Education and Research (CHEER) (2011) ‘The contribution of South African curricula to prepare health professionals for working in rural or under-served areas in South Africa: A peer review evaluation’, South African Medical Journal, 101(1): 34–8.

Reid, S.J., Volmink J. and Couper, I.D. (2011) ‘Educational factors that influence the distribution of health professionals in South African public service: A case control study’, South African Medical Journal, 101(1): 29–33.

Ross, S., Preston, R., Lindemann, I., Matte, M., Samson, R., Tandinco, F., Larkins, S., Palsdottir, B. and Neusy, A-J. (2014) ‘The training for health equity network evaluation framework: A pilot study at five health professional schools’, Education for Health, 27(2): 116–26.

Rural and Northern Health Care Panel (2010) Rural and northern health care framework/plan, stage 1 report. Final report. Toronto: Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care. Online. Available HTTP: http://www.health.gov.on.ca/en/public/programs/ruralnorthern/docs/report_rural_northern_EN.pdf (accessed June 2013).

Sales, C.S. and Schlaff, A.L. (2010) ‘Reforming medical education: A review and synthesis of five critiques of medical practice’, Social Science and Medicine, 70(11): 1665–8.

Sen Gupta, T.K., Murray, R.B., Beaton, N.S., Farlow, D.J., Jukka, C.B. and Coventry, N.L. (2009) ‘A tale of three hospitals: Solving learning and workforce needs together’, Medical Journal of Australia, 191(2): 105–9.

Sen Gupta, T., Woolley, T., Murray, R., Hay, R. and McCloskey, T. (2014) ‘Positive impacts on rural and regional workforce from the first seven cohorts of James Cook University medical graduates’, Rural and Remote Health, 14(1): 2657.

Strasser, R. (2010) ‘Community engagement: A key to successful rural clinical education’, Rural and Remote Health, 10(3): 1543.

Strasser, R. and Hirsh, D. (2011) ‘Longitudinal integrated clerkships: Transforming medical education worldwide?’, Medical Education, 45(5): 436–7.

Strasser, R. and Neusy, A.J. (2010) ‘Context counts: Training health workers in and for rural areas’, Bulletin of the World Health Organization, 88(10): 777–82.

Strasser, R.P., Lanphear, J.H., McCready, W.A., Topps, M.H., Hunt, D.D. and Matte, M.C. (2009) ‘Canada’s new medical school: The Northern Ontario School of Medicine – social accountability through distributed community engaged learning’, Academic Medicine, 84(10): 1459–64.

Strasser, R., Hogenbirk, J.C., Minore, B., Marsh, D.C., Berry, S., McCready, W.A. and Graves, L. (2013) ‘Transforming health professional education through social accountability: Canada’s Northern Ontario School of Medicine’, Medical Teacher, 35(6): 490–6.

Tesson, G., Hudson, G., Strasser, R. and Hunt, D. (eds) (2009) Making of the Northern Ontario School of Medicine: A case study in the history of medical education, Kingston, Ontario: McGill-Queen’s University Press.

Training for Health Equity Network (2011) THEnet’s social accountability evaluation framework version 1. Monograph I (1 ed.), Belgium: The Training for Health Equity Network. Online. Available HTTP: http://thenetcommunity.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/05/The-Monograph.pdf (accessed June 2014).

Training for Health Equity Network, THEnet (2013). Online. Available HTTP: http://thenetcommunity.org/ (accessed June 2013).

Wilson, N., Couper, I., de Vries, E., Reid, S., Fish, T. and Marais, B. (2009) ‘A critical review of interventions to redress the inequitable distribution of healthcare professionals to rural and remote areas’, Rural and Remote Health, 9(2): 1060.

World Health Organization (2010) Increasing access to health workers in remote and rural areas through improved retention: Global policy recommendations, Geneva: World Health Organization.