6

HOW DO WE SELECT STUDENTS WITH THE NECESSARY ABILITIES?

Jon Dowell

The last two decades have witnessed dramatic changes in how we view the science and art of selecting students for admission to medical studies.

Recent decades have witnessed dramatic changes in how we view the art of selecting medical students as the evidence evolves (Cleland et al. 2013). High academic ability alone is no longer considered sufficient and sound interpersonal skills and attitudes are increasingly considered fundamental. Although it is sometimes argued communication skills or even professional behaviour can be taught, it is logical to select the best in multiple domains where we have opportunity, as it makes teaching easier and higher competence achievable. In this chapter we shall briefly consider why selection matters and what it seeks to achieve before examining some of the available tools and exploring practical issues such as resources, legal frameworks and context.

So why does selection matter? Firstly, medical training universally recruits academically elite students with great potential and then invests hugely in them. Typically at least 90 per cent of entrants graduate, so selection plays a key role in determining this human and financial ‘resource’ use. Medicine also plays a significant societal role; it is highly competitive, very influential and carries high status. We all want ‘good doctors’ and not ‘bad doctors’, two dimensions of selection we shall return to later.

In practice, a wide range of approaches to selection have been adopted around the world, reflecting the lack of clear evidence. Countries such as France allow any student to enter a medical course and then robustly select after the first year of studies. The Dutch have historically used a lottery allocation for those of high academic ability but are increasingly moving to a more selective system like those operated by most Western countries. The latter generally operate systems that include a range of applicant attributes, albeit in very different ways. Academic achievement is a universal element but increasingly this is supplemented with aptitude tests such as: (1) Medical College Admissions Test (MCAT) in the USA; (2) United Kingdom Clinical Aptitude Test (UKCAT); (3) Graduate Medical Schools Admissions Test (GAMSAT) in Australia; (4) Biomedical Admissions Test (BMAT) in the UK; and (5) Health Professions Admissions Test (HPAT) in Eire, and there is new interest in interviews based on a highly structured approach, the Multiple Mini-Interview (MMI). In addition, disappointing evidence has emerged from evaluations of personality measures as well as some longstanding tools such as personal statements and references (that may be particularly vulnerable to ‘gaming’, cheating and other influences such as applicant’s background). So the weight placed on these traditional measures is being challenged.

Selection never exists in a vacuum and local workforce issues as well as those of gender, ethnic and socio-economic equity are always at play. The local nature and complexity of these require local resolutions and the first case study from Pakistan illustrates how Aga Khan University addresses equal opportunity through a ‘needs-blind’ policy.

Case study 6.1 Selecting students with the necessary abilities, Aga Khan University, Pakistan

Rukhsana W. Zuberi and Laila Akbarali

Aga Khan University (AKU), chartered in 1983, was Pakistan’s first private university and, according to the country’s Higher Education Commission, is one of its premier institutions. It is a not-for-profit international university with campuses in south-central Asia, East Africa and the UK. The university’s Medical College admits 100 students annually to a 5-year undergraduate medical (MBBS) degree programme. The Registrar’s Office is responsible for admissions. Student selection is aligned to AKU’s vision and mission and the underpinning philosophy of quality, accessibility, relevance and impact. It is not only essential to select students with the right abilities; it is also essential to be accessible to such students.

AKU admissions are responsive to social accountability. To ensure that distance or travel-related costs do not preclude applicants, either from less-privileged areas of Pakistan or from international sites, the University Admission Test (UAT) is conducted in several cities in Pakistan and in seven centres around the world (London, Dar-es-Salaam, Toronto, Nairobi, Kampala, New York, Dubai), and, more recently, in Bangladesh, Singapore and Malaysia. The university makes every effort to accommodate a candidate’s request to conduct the test close to his or her home town.

Although not the first language in Pakistan, English is the language of instruction at AKU. To improve accessibility from underprivileged areas, English scores are reported separately when shortlisting candidates. Thus, students with high cumulative scores in UAT’s science component (mathematical reasoning, science reasoning, science achievement based on assimilation of knowledge) but less than average English scores can be identified and coached in English if admitted.

Approximately 4,000 candidates apply each year, with roughly the top 10 per cent selected for interviews. The interviews are also scheduled close to candidates’ home towns. Within Pakistan, faculty members travel to seven different cities to carry out the interviews; for interviews conducted outside Pakistan, wherever possible, Medical College alumni are utilised.

The Medical College’s interview form has been designed to assess 11 attributes that also keep in mind the opportunities available to the candidates. These attributes are responsibility; maturity; independent and critical thinking; honesty and integrity; adaptability and tolerance for others; socio-cultural awareness; health awareness; communication skills; motivation, interest and commitment to the medical profession; teamwork and leadership potential; and their aspirations in life.

Faculty training workshops for student selection are held to increase inter-rater reliability, and to hone faculty interviewing and narrative-writing skills. The interviews are conducted by two faculty members: either a basic scientist or a community health scientist and a clinician. Each interview is conducted separately and lasts about half an hour. Interviewers are not privy to test scores or scholastic achievements of the candidate. They are required to provide a narrative for each of the 11 characteristics, and an overall assessment regarding the suitability of the candidate for AKU.

The Admissions Committee is chaired by the Dean and consists of seven members from within AKU (including the Chair of the Examinations and Promotions Committee; Associate Dean Education and the University Registrar), an AKU alumna/alumnus, a non-AKU educationist and four eminent citizens of Karachi.

In making its decisions, the Admissions Committee has access to the candidates’ secondary school certificate scores (or British and American school system equivalents), the UAT scores (or SAT scores for international candidates). Group percentiles of the test scores are also available to members of the Admissions Committee.

Each candidate’s profile is presented anonymously to the Admissions Committee for consideration. The profile includes the candidate’s application and personal statement, certificates from school, the two complete interview reports and two school recommendations. Committee members use a scale from one to four to provide their feedback on each candidate; the top hundred are selected.

Needs-blind admission policy

Once admitted, a student’s ability to pay is determined. Interest-free financial assistance is available for tuition, fees, hostel accommodation and a subsistence allowance, as needed. No student is denied admission on the basis of financial constraints.

Candidates are short-listed based on knowledge and reasoning ability, and selected based on humanistic, extracurricular and leadership abilities. The 11-member Admissions Committee ensures reliability and validity of decisions made.

Studying medicine is a high-status activity subject to competitive selection. Thus, attention to the process is important and is often contentious. Ideally a clear legal framework would support open, fair and transparent selection processes, which would in turn result in a diverse population of students broadly representative of inhabitants. Demonstrably reliable and valid measures of academic and non-academic attributes would be used and these would then show meaningful predictive validity, both during training and beyond. All this would be done at reasonable cost and in a manner acceptable to candidates and others. Unfortunately, we are not there yet but it is likely we shall take some significant steps forward in the coming decade. We should not forget though that each individual’s decision to apply is the primary determinant of who enters, not our selection methods.

Context

Globally there is interest in who gains access to study medicine, partly because it reflects our societies’ particular racial, gender, religious or other issues interacting with what is generally portrayed as a ‘fair’ process. For instance, efforts are made to increase black and Hispanic entrants in the USA, and native Aboriginal entrants in Canada and Australia. In the UK context (known best to the author) there is longstanding evidence that those from lower socio-economic classes rarely apply for medical school and fare a little less well when they do (Cleland et al. 2013: 49). This is despite numerous initiatives and considerable investment in outreach, bespoke supported and extended courses and some positive discrimination within selection. A number of studies have shown how strong cultural factors influence potential applicants’ choices, with medicine in the UK being viewed as a ‘posh club’. Whatever the contextual issue, they can usefully be separated into distinct elements that can be considered and addressed individually. Namely:

• getting ready;

• getting in;

• staying in;

• getting on.

There are four core reasons why it is important to consider how local context influences the individuals who study medicine: equity, optimising potential, impact on learning and impact on workforce. First, as a highly competitive, high-profile subject medicine is a barometer of opportunity within societies. Second, to identify the best it is necessary to seek those with most potential from the broadest base available. Unless the necessary attributes required are absent from some applicant groups all individuals with suitable potential should be encouraged. Third is the influence a broad mix of students can have within a school and the learning that occurs there, for instance towards ethnicity, sexuality or disability. Last, there is emerging evidence that career choice depends to some extent on origin, with doctors more likely to return to and serve rural or deprived home communities.

This UK case study demonstrates how some medical schools have sought to broaden selection more robustly to include non-cognitive attributes.

Case study 6.2 Assessing non-academic attributes for medical and dental school admissions using a situational judgement test, United Kingdom

Fiona Patterson, Emma Rowett, Máire Kerrin and Stuart Martin

Applicants to UK university medical and dental schools are of a consistently high calibre with regard to their academic qualifications; the UKCAT (UKCAT 2014) is used by a consortium of universities to help them make more informed choices from among the many highly qualified applicants who apply for the medical and dental degree programmes. Until 2013, the UKCAT consisted of tests of verbal, quantitative, abstract reasoning and decision-making analysis.

Role analyses of numerous specialties in the medical and dental arena have indicated that non-academic or professional attributes (such as integrity and team working) are essential requirements for a clinician. Situational judgement tests (SJTs) are an increasingly popular and well-established selection method for assessing these non-academic attributes. SJTs are a measurement method and, in an SJT, candidates are presented with challenging hypothetical situations which are likely to be encountered in the target role, where candidates are required to make a judgement on the effectiveness of various response options. The responses of candidates are scored against a pre-determined key agreed by subject matter experts. Once designed, SJTs are cost-effective to score and administer, and research indicates that SJTs have significant validity in predicting role performance over and above both IQ tests and personality tests (McDaniel et al. 2001; McDaniel and Whetzel, 2007; Patterson et al. 2009, 2012). Other benefits of SJTs are that they generally have smaller subgroup differences than cognitive ability tests (Lievens et al. 2005), favourable candidate reactions and high face validity. In addition, certain response formats can minimise susceptibility to coaching, which is an important consideration in selection for medicine.

In order to assess non-academic attributes in applicants to medical and dental schools, a newly designed SJT was piloted in 2011–12 and since 2013 has been used for live medical and dental school admissions. The SJT scenarios used in the UKCAT are based on analyses of medical/dental roles but do not require any clinical knowledge as it is important that the test is fair and appropriate for a novice population.

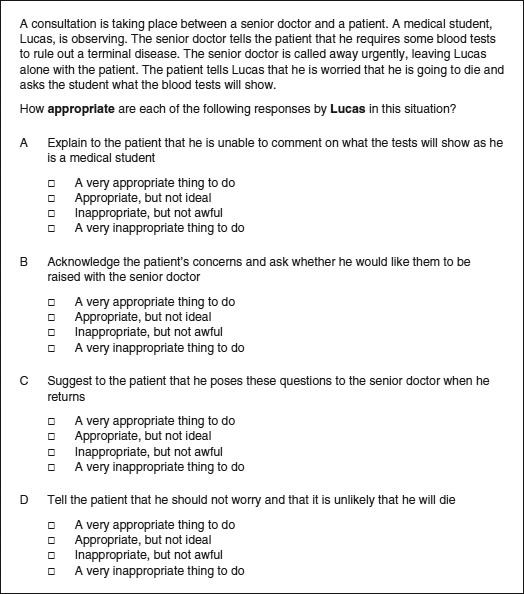

Figure 6.1 Example SJT item.

The UKCAT SJT targets three domains: integrity, perspective taking and team involvement. The 2012 pilot test content was developed by subject matter experts (n = 38) and experienced psychometricians (n = 5). The SJT presents candidates with a set of hypothetical scenarios which are based in either a clinical setting or during educational training as a student. Scenarios may involve a student, patient or clinician, and each targets one of the three domains which has been identified as being important to the role of a medical or dental student.

In 2012, 18 test forms were piloted online alongside the other UKCAT subtests. A total of 25,431 applicants sat the pilot. Each SJT scenario asked applicants to rate between four and six response options and two formats of rating scales (1 to 4 scale) were used: very appropriate to not appropriate at all and very important to not important at all. An example SJT item is provided in Figure 6.1.

Candidates’ responses to SJT items were evaluated against a pre-determined scoring key to provide a picture of their situational judgement and marks were assigned dependent on response proximity by the candidate to the correct answers. Full marks for an item were awarded if a candidate’s response matched the agreed expert key and partial marks were awarded if the response was close to the agreed correct answer.

Psychometric analysis of the pilot SJT demonstrated good levels of reliability (α = 0.75–0.85). Initial evidence of criterion-related validity was established as applicant scores on the SJT correlated significantly with the other UKCAT subtests. On average, the SJT correlated more strongly with the verbal and decision-making analysis test than with the numerical and abstract tests. However, the sizes of the correlations were moderate (as expected), as the SJT is designed to measure non-academic attributes that are important for anyone embarking on a career within medicine and dentistry. Unlike academic indicators used in selection (such as A levels), early results show that performance on the SJT is not related to socio-economic status, which is an important finding in relation to a broader widening participation agenda.

SJTs offer a standardised method of objectively assessing a broad range of professional role-related attributes in large numbers of applicants, and demonstrate face validity to candidates because the scenarios used in SJTs are based on relevant situations (Patterson et al. 2012). Outcomes from the UKCAT SJT demonstrated that an SJT is a reliable and valid selection methodology for testing important non-academic attributes for entry to medical and dental school.

Medical school selection needs to be fit for purpose in the local context. To achieve a desirable mix within the final workforce and deliver a fair and open process may require quite different systems in different countries or regions. The same principles, however, are likely to apply.

Academic ability

Academic ability, or more specifically, academic achievement in terms of exam performance at school or university, has been the mainstay of medical school selection for generations. It remains the most obviously justifiable way of separating candidates and has the best evidence base in terms of predicting future exam performance, and to a lesser extent in postgraduate assessments. However, there are also a number of concerns about utilising measures of achievement too heavily and an awareness that exam grades are not the only outcome of importance.

Generally measures of achievement are freely available and quantified reliably because they result from quality-assured assessment at school or university. There is clear face validity in requiring medical students to be high performers, which is supported by moderate levels of predictive validity. Because medicine is oversubscribed, one option is simply to select the very best academically. However this risks two things. First, achievement may often not be easily compared or reflect true potential because educational opportunity is not equal. Even in countries with little variation in the quality of education, applicants will receive widely different levels of home support and encouragement. One approach to moderating this is universal testing, which tries to compare applicants more fairly, at least partly by measuring stable aspects of so-called ‘fluid intelligence’, known to be less dependent on education and background. A number of such tests have now been developed which vary in their format and content, reflecting the context in which they were developed. Availability, cost and content all require consideration. For instance, although research on MCAT 2013 shows it is the science component that best predicts performance, the UKCAT 2103 chose a pure aptitude test format. This was because a key aspiration was to help ‘widen access’ in the UK and a lower level of predictive validity was traded against a test focused on ‘potential’.

So, prior achievement should be viewed in local context. Though tempting simply to select the highest achievers, it may be more logical to consider ‘how good is good enough’. This opens the door to consider what other attributes educators require from entrants.

There are a number of reasons why other attributes may be worth considering. First, there is an argument that those presenting with broader talents have some ‘reserve in the tank’ for when the going gets tough. More importantly, it is clear that patients require clinicians to offer more than academic brilliance alone. In modern healthcare settings, high value is placed upon interpersonal communication skills, attitudes, integrity and an ability to work effectively within multidisciplinary teams. Medical schools are increasingly seeking to ensure that assessments of such aptitudes are included in selection, as demonstrated in the UK case study. The problem is that validated and justifiable measures of these attributes are only just emerging.

Non-academic attributes

Despite long-term interest in the non-academic attributes of doctors, the evidence base remains weak. Even the terminology, non-academic versus non-cognitive, remains disputed. This is not good news for high-stakes selection systems where a sound evidence base justifies use of academic grades while primarily strong beliefs support the inclusion of ‘softer skills’.

Despite the lack of convincing evidence, non-academic attributes have often been applied, including personal statements, character references, personality tests and various forms of interviews. Unfortunately none has stood up to rigorous scrutiny and, as a result, a range of alternative approaches is being developed and tested.

Foremost among these is now the structured interview and in particular the MMI. This system, based upon the Objective Structured Clinical Examination (OSCE), has consistently demonstrated satisfactory reliability and its use is spreading rapidly based on evolving evidence of predictive validity within medical school and even beyond. The Canadian case study discusses the introduction of the MMI into medical school admissions. As selection science develops further it seems likely that selection centres will evolve, as is the case in Israel (Gafni et al. 2012: 277).

Case study 6.3 The true fairy tale of the Multiple Mini-Interview, McMaster University, Canada

Harold I. Reiter and Kevin W. Eva

The apocryphal story held that the daughter of a neighbour to a dean or associate dean, having clearly demonstrated to all who knew her that she was the fairest medical school applicant in the land, nevertheless failed to secure an offer of admission to her local medical school. A retreat was called to review the admissions processes of all schools in McMaster University’s health science kingdom. By this time, the process of medical school admissions had devolved into a labyrinthine path, as one well-intended process correction followed another, each correction solving one perceived problem while creating new difficulties. Concerned with the defensibility of his realm, the Earl of Admissions sought support from a neighbouring village of faculty with broader experience in assessment.

At a meeting to discuss possible research on OSCE feedback, 5 minutes were set aside to consider a response to the plea from the Earl of Admissions. Ideas were batted about, including the concept of an ‘admissions OSCE’, but the concept was immediately discarded (with much laughter) due to the perception of overwhelming resource requirements. There the idea would have died had not one member, that weekend, put quill to parchment and realised that less gold would be needed to run an admissions OSCE than to continue with the traditional interview system (Rosenfeld et al. 2008). At the kingdom’s retreat the idea garnered sufficient support to merit $5,000 (CAD) in seed funding from the faculty. A small 2001 pilot study of 18 graduate students and a six-station MMI yielded sufficient promise to lead our protagonists to continue their quest (Eva et al. 2004).

As supportive evidence in the form of improved test–retest reliability, feasibility and acceptability rolled in over subsequent studies with real applicants, the parry and thrust that ultimately won the argument was that the absence of evidence regarding predictive validity of the MMI was better than evidence of the absence of predictive validity that was available for any of the measures of personal characteristics in traditional use (Kulatunga-Moruzi and Norman 2002). At least the MMI had the potential for validity, which was only later realised (Reiter et al. 2007; Eva et al. 2009, 2012).

The process of ridding the kingdom of dragons, however, was not entirely painless as many knights of the Admissions Committee were resistant, having invested immeasurably in the traditional practices. For those knights, the MMI was anathema to all that they knew to be good and true in the world and intellectual arguments could not sway their emotional attachments. The new Earl of Admissions, committed to sweeping changes of which the MMI was an integral part, faced the dual tasks of fighting a rearguard action and supporting innovative development. After initial raucous committee meetings, it was necessary to reorganise the committee and terms of reference were written that required, henceforth, all knights to prove their mettle with an assigned ‘portfolio’ (e.g. the MMI, the autobiographical submission, research of newer tools) or relinquish their knighthood. Each portfolio required a specific skill set that included a willingness to look beyond convictions that one ‘knew’ who would become good doctors.

Community buy-in from the villagers proved the easiest to achieve as the Earl of Admissions sought out to draw upon the broad and variable expertise present in the land. To mount an MMI well with structured interview stations requires an assessment blueprint, so a paired comparison survey was sent throughout the realm to enable many stakeholders from across the kingdom to define the relative importance to be placed on various applicant characteristics (Reiter and Eva 2005). Villagers were also recruited as MMI station writers and interviewers, lending an additional medieval faire-like air to the MMI dates.

While there remain questions to be answered, the proverbial genie that is the MMI is now out of the bottle. Based upon research diligently conducted within a culture of evidence-based decision making and with the support of the Deanery, the MMI was implemented in 2004. In hindsight, each of these factors, scientific and political, were necessary components for its coming to fruition. Since then, at least 80 papers have been published on the MMI (www.tinyurl.com/mmiresearch), most emanating from outside of McMaster. At last count, close to a quarter of Canadian and American medical schools are using the MMI, along with countless other health professional schools worldwide (Eva et al. 2012). As the MMI is a process rather than an instrument, its use will vary from place to place. Our experience would lead us to believe, however, that universal factors enabling successful implementation include: (1) recognition of a problem; (2) collaboration between individuals with complementary expertise; (3) a spirit of innovation; (4) dedicated scholarship; (5) strong leadership; and of course, (6) a healthy dose of serendipity.

Although interviews appear to be the method of choice for assessing interpersonal skills, they typically also include assessments of critical thinking, integrity or moral reasoning, which make less sense. In a face-to-face format it is very costly to present a satisfactory number of situations to candidates and is difficult to grade them consistently enough. By contrast, SJTs, as described in the UK case study above, appear to offer this potential (Cleland et al. 2013: 29). These tests, which present candidates with a series of dilemmas and require them to rank a range of responses, have been shown to be reliable and offer an interesting new tool with high face validity.

By contrast, personality tests have now been extensively assessed without finding favour, perhaps because of fears over ‘faking’ in high-stakes situations and, although reliability is high, predictive validity has been very limited (Cleland et al. 2013: 34).

So it seems quite feasible that within the next 5–10 years a valid system for evaluating non-academic skills will develop and, as the evidence base emerges, the currently diverse range of practices will converge around those techniques known to be cost-effective. Of course the competitive nature of medical selection will continue and it remains to be seen how immune these approaches will be from coaching effects.

The bigger picture

Medical practice varies around the globe and, although a need for high academic ability may be universal, there may be great local variation in the non-academic qualities required. For instance, different weight may be put upon communication skills or patient-centred attitudes within different healthcare systems. Others may prioritise resilience or personal motivation, and others select for those with a particular focus on rural service. Each will require and want a somewhat different emphasis within its selection system. So the question of how different elements are used and combined emerges. For instance, different scores can be used as hurdles or combined into a summary rank. Some or even all elements may be multiplied to introduce an adjustment for educational or personal adversity (so-called contextual assessment). Selectors may wish to include systems capable of deselecting otherwise promising individuals for reasons not explicitly included within the scoring algorithm, such as deception within the application process or even unacceptable attitudes (e.g. racism). All of this must be considered with an awareness of the strengths and weaknesses of the information available. For instance, professional references may be valuable in some cultures but not in all. However, beyond any direct impact on selection, the system chosen will have a potentially far larger effect by influencing who applies.

Hence, it is necessary to consider what you wish to prioritise and whether the process suits the mission of the institution. In addition, it is important to ensure that the decision-making process has balance and is not dominated by any particular perspective. The constitution of the relevant guiding body or committee should include broad representation, including patient or lay members to counter the narrow focus of academic staff.

A framework for selection

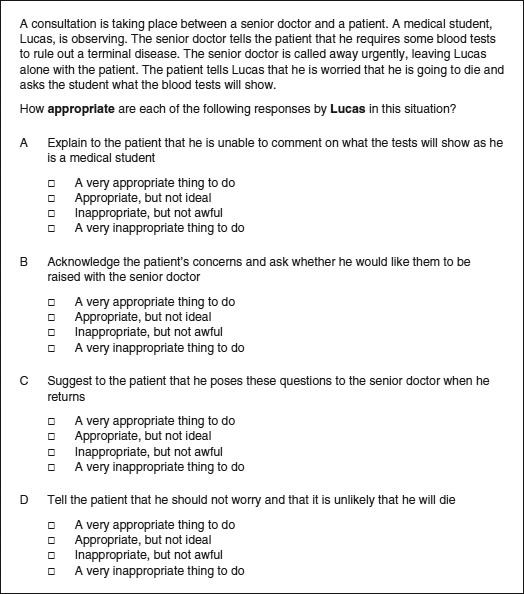

Figure 6.2 demonstrates an integrated framework for selection of medical students.

The way such a schema might be operated is outlined below. Assessments on each domain may be used to identify concerning individuals whose progress will be barred (‘hurdles-based’) as well as contributing to a rank for those remaining.

Academic

Academic achievement, with or without the addition of aptitude testing, will continue to form the backbone of selection systems. Because academic assessments are widely accepted, cheap and reasonably reliable and valid it is clearly appropriate to continue using these as a primary filter or screening tool.

Attitudinal/behavioural

Attitudinal or behavioural attributes may be measured through SJTs or at interview or even personality inventories (Goldberg ‘Big 5’ Personality Test, Personal Qualities Assessment). They may then be used in conjunction with some or all of the other scores available or in their own right, for instance, to exclude those with highly aberrant views. It may be possible and appropriate to include other sorts of evidence here, such as previous legal convictions or references, if a robust system exists.

Interpersonal communication

Broad consensus over the importance of interpersonal communication skills has led to the widespread use of interviews. Often, however, the elements of communication being assessed are ill defined. They will include an assessment of the ability to interact effectively on a one-to-one basis but increasingly, more refined and sophisticated challenges are presented (for example, the ability to convey empathy within role-play situations). The MMI is clearly emerging as a leading methodology.

Other attributes?

There are a number of other attributes that schools might consider depending on their circumstances. Examples include: motivation to study medicine or at that specific school, career awareness, language abilities or an interest in serving a particular community. Specifically, an assessment of ‘fitness to practise’ as a clinician may sometimes be required due to individual circumstances such as disability (Higher Educational Occupational Physicians 2011) or probity. The Dutch case study offers an example of how satisfactory performance in multiple areas can be used to ‘select out’.

Case study 6.4 Consequences of ‘selecting out’ in the Netherlands

Fred Tromp and Margit I. Vermeulen

The Dutch postgraduate training for general practice (GP) has a nationally endorsed curriculum. The Departments of General Practice of the eight university medical centres are responsible for the organisation of the 3-year postgraduate training.

The Dutch selection procedure of GP training was studied by Vermeulen et al. (2012). This procedure, which consists of selection on the basis of a letter of application and a semi-structured interview, is nationally legislated but locally conducted. It was found that, despite legislation, different standards were used across different institutes and that the department itself was a strong predictor of being admitted. Viewing the results of their study, the authors expressed their concerns regarding the fairness of the selection procedure and pleaded for a rethink of the current approach.

Since 2010, a fair, standardised selection procedure has been developed. Because of the decreasing number of candidates in relation to available vacancies and the societal responsibility to ensure qualified GPs, a selecting-out approach was chosen. The new procedure aimed to identify unsuitable candidates who are likely to encounter difficulties and will not finish the training successfully. Despite the fact that most candidates finish the training successfully in the Netherlands, drop-outs and poor performers cost the departments a large amount of effort and money. In addition, their places cannot be reallocated, which is a waste of capacity.

The first step in the development of the procedure was a content analysis to establish the required level of competence. The curriculum of GP training in the Netherlands is based on the Canadian Physician Competency Framework (CanMEDS) competencies. To determine which of these competencies should be targeted for the selection procedure for GP training, we invited a panel of 16 experts. In a Delphi procedure the panellists determined ‘which of the CanMEDS-competencies should already be present before entering GP training in order to finish the training successfully’. The second step was to determine which assessment instruments to use. In a high-stake situation, no single assessment instrument can provide the necessary information for judgement (van der Vleuten and Schuwirth 2005; Prideaux et al. 2011). Therefore, four instruments were included to assess competencies needed to start the training: the Knowledge Test for General Practice; an SJT; three mini-simulations (SIMs); and a Patterned Behaviour Descriptive Interview (PBDI).

After the candidates completed all instruments, the assessments were aggregated and substantiated by the assessors involved. As the instruments provided incremental information of the candidates’ competencies, appropriate recommendations could be made. Candidates were accepted after establishing whether all targeted competencies were present to a certain extent. This means that if one competency could not be shown by the candidates, they were rejected no matter how high the other scores were (see examples below).

Example 1

A female candidate, 25 years old, applied for the first time. She graduated with honours and started 6 months ago as an MD in an emergency room. She scored high on all instruments, except on one competency in the PBDI – self-care. Lack of self-care is a well-known cause of problems during the GP training.

Example 2

A male candidate, 33 years old, applied for the first time. He already had a lot of different working experience as an MD. He scored high on all instruments, except on one competency in the SIM: showing respect to the patient. He patronised the patient and was very judgemental towards the patient. Afterwards he did not show any reflection on his behaviour.

We realise rejection is hard to comprehend for these particular candidates, as they performed well in general. Therefore, formulating the required level of competency unambiguously and clearly is of utmost importance. Our new procedure is transparent, and the candidates are informed which competencies will be assessed and that a deficiency cannot be compensated for. Extensive feedback was provided to the rejected candidates, which is important because this enables candidates to remedy their deficiencies so that they can reapply. Feedback to admitted candidates can be used at the start of the training.

Ranking and selecting out

Once applicants have survived the initial screening process, progressed through whatever subsequent assessments are required and made it into the final cohort, some form of final selection is required. In theory this entire group should be very suitable entrants to study medicine and many would argue that a random allocation system would be fairest at this point. Historically, however, it is more common to rank applicants and invite the ‘best’. Ideally this is based upon an analysis of the way in which the respective components of the selection system operates locally, for instance, how strongly different components predict performance on the course. Often, however, this level of evidence is lacking and a decision must be based upon the views of an admissions committee, preferably with intimate knowledge of the system in practice.

Assessing success

A recurrent theme of this chapter has been the challenge of validating admissions tools without a suitable range of outcome measures. We know that patients highly value clinicians’ interpersonal skills and there is a consensus that teamwork is important for patient safety. However medical schools do not typically measure these attributes distinctly. As more reliable and valid means of selecting students emerge it is increasingly important to ensure these are benchmarked against appropriate outcome markers and not simply knowledge-based tests. And although we will never identify and avoid all unsuitable entrants, it is important to study rare events such as fitness-to-practise concerns. We are at an interesting stage in the evolution of selection techniques with the advent of new tools such as SJTs and MMIs. To make significant progress with this agenda, long-term follow-up studies are required which include issues such as career choice and satisfaction as well as undergraduate performance.

Take-home messages

• Selection for medical school is a complex and contentious task which is currently based on an inadequate evidence base.

• There are a number of promising initiatives arising, in particular the advent of the MMI and greater use of aptitude testing in addition to prior academic achievement and the development of tools such as the SJTs.

• It must be recognised that medical education exists in widely varied contexts, educational institutions and societies, with different expectations and different workforce requirements. All of these will have a local effect in determining what approach is appropriate.

• It certainly seems desirable to use an approach which balances achievements in both academic and non-academic areas and which is capable of selecting out the minority of unsuitable applicants as effectively as it ranks the high achievers.

• In a perfect world, markers of both academic and non-academic attributes would be both reliable and valid predictors of future performance. At present though we are some way off this ideal and require some sophisticated long-term studies to achieve it. However this is an area of medical education worth watching over the coming years.

Bibliography

Admission Testing Service (2014) About the Biomedical Admission Test (BMAT). Online. Available HTTP: www.admissiontestingservice.org/our-services/medicine-and-healthcare/bmat/about-bmat (accessed 22 May 2014).

Association of American Medical Colleges (2013) Medical college admission test. Online. Available HTTP: https://www.aamc.org/students/applying/mcat/about/ (accessed 22 June 2013).

Australian Council for Educational Research (2013a) Graduate medical schools admissions test. Online. Available HTTP: http://gamsat.acer.edu.au/about-gamsat (accessed 22 June 2013).

Australian Council for Educational Research (2013b) Health professions admissions test: Ireland. Online. Available HTTP: http://www.hpat-ireland.acer.edu.au (accessed 22 June 2013).

Cleland, J., Dowell, J., McLachlan, J., Nicholson, S. and Patterson, F. (2013) Identifying best practice in the selection of medical students, London: GMC. Online. Available HTTP: http://www.gmc-uk.org/Identifying_best_practice_in_the_selection_of_medical_students.pdf_51119804.pdf (accessed 22 June 2013).

Eva, K.W., Rosenfeld, J., Reiter, H.I. and Norman, G.R. (2004) ‘An admissions OSCE: The Multiple Mini-Interview’, Medical Education, 38: 314–26.

Eva, K.W., Reiter, H.I., Trinh, K., Wasi, P., Rosenfeld, J. and Norman, G. (2009) ‘Predictive validity of the Multiple Mini-Interview for selecting medical trainees’, Medical Education, 43: 767–85.

Eva, K.W., Reiter, H.I., Rosenfeld, J., Trinh, K., Wood, T.J. and Norman, G.R. (2012) ‘Association between a medical school admission process using the Multiple Mini-Interview and national licensing examination scores’, Journal of the American Medical Association, 308: 2233–40.

Gafni, N., Moshinsky, A., Eisenberg, O., Zeigler, D. and Ziv, A. (2012) ‘Reliability estimates: Behavioural stations and questionnaires in medical school admissions’, Medical Education, 46(3): 277–88.

Higher Educational Occupational Physicians (2011) Medical students – Standards of medical fitness to train. Online. Available HTTP: http://www.heops.org.uk/HEOPS_Medical_Students_fitness_standards_2013_v10.pdf (accessed 23 March 2105).

Kulatunga-Moruzi, C. and Norman, G.R. (2002) ‘Validity of admissions measures in predicting performance outcomes: A comparison of those who were and were not accepted at McMaster’, Teaching and Learning Medicine, 14: 43–8.

Lievens, F., Buyse, T. and Sackett, P. (2005) ‘The operational validity of a video-based situational judgement test for medical college admissions: Illustrating the importance of matching predictor and criterion construct domains’, Journal of Applied Psychology, 90(3): 442–52.

McDaniel, M. and Whetzel, D. (2007) ‘Situational judgement tests’, In G.R. Wheaton and D.L. Whetzel (eds) Applied measurement: Industrial psychology in human resources management, Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

McDaniel, M., Morgeson, F.P., Finnegan, E.B., Campion, M.A. and Braverman, E.P. (2001) ‘Use of situational judgement tests to predict job performance: A clarification of the literature’, Journal of Applied Psychology, 86(4): 730–40.

Patterson, F., Carr, V., Zibarras, L., Burr, B., Berkin, L., Plint, S., Irish, B. and Gregory, S. (2009) ‘New machine-marked tests for selection into core medical training: Evidence from two validation studies’, Clinical Medicine, 9(5): 417–20.

Patterson, F., Ashworth, V., Zibarras, L., Coan, P., Kerrin, M. and O’Neill, P. (2012) ‘Evaluating situational judgement tests to assess non-academic attributes in selection’, Medical Education, 46: 850–65.

Prideaux, D., Roberts, C., Eva, K., Centeno, Aa, McCrorie, P., McManus, C., Patterson, F., Pavis, D., Tekian, A. and Wilkinson, D. (2011) ‘Assessment for selection for the health care professions and specialty training: Consensus statement and recommendations from the Ottawa 2010 Conference’. Medical Teacher, 33: 215–23.

Reiter, H.I. and Eva, K.W. (2005) ‘Reflecting the relative values of community, faculty, and students in the admissions tools of medical school’, Teaching and Learning in Medicine, 17: 4–8.

Reiter, H.I., Eva, K.W., Rosenfeld, J. and Norman, G.R. (2007) ‘Multiple mini-interview predicts clerkship and licensing exam performance’, Medical Education, 41: 378–84.

Rosenfeld, J., Reiter, H.I., Trinh, K. and Eva, K.W. (2008) ‘A cost efficiency comparison between the multiple mini-interview and traditional admissions interviews’, Advances in Health Sciences Education, 13: 43–58.

UK Clinical Aptitude Test (2014) UK Clinical Aptitude Test. Online. Available HTTP: http://www.ukcat.ac.uk/ (accessed 23 March 2015).

van der Vleuten, C.P.M. and Schuwirth, L.W. (2005) ‘Assessing professional competence: From methods to programmes’, Medical Education, 39: 309–17.

Vermeulen, M.I., Kuyvenhoven, M.M., Zuithoff, N.P.A., Tromp, F., Graaf van der, Y. and Pieters, H.M. (2012) ‘Selection for Dutch postgraduate GP training: Time for improvement’, European Journal of General Practice, 18: 201–5.