The students’ role and how they can be engaged with the curriculum

The benefits to be gained from significant student engagement in medical school activities are now widely appreciated.

Relationships between students, teachers and their educational institutions have changed dramatically over recent decades. What had been seen as unidirectional learning from teacher to student is now increasingly seen as more symbiotic. In some countries the model of financing education has changed, with a corresponding shift from seeing students as the recipients of education to that of consumers. In addition, changing emphases in delivery and modes of learning have promoted the requirement of ‘active’ and ‘engaged’ learning while at the same time increasing the opportunities for students to learn remotely and at a distance. Combined together, these and other changes have increased the significance of student engagement in medical education. In this chapter we will explore the differing perspectives of what student engagement is and how it can be promoted and explore the experiences at a number of case study institutions.

What is ‘student engagement’?

In higher education there is growing interest in student engagement, in the ‘student voice’ and in staff working in partnership with students to deliver the education programme and to facilitate change (Baron and Corbin 2012). Many perceived benefits are often highlighted for students, such as improving student experience and achievement, and for institutions as an indicator of success, quality assurance and competitive advantage. However, understandings of what ‘student engagement’ is vary between individuals, their disciplines, institutions and countries.

The term ‘student engagement’ can be traced to debates about student involvement, and is a term in common use, particularly in North America and Australasia, where annual large-scale student engagement surveys have been conducted for a number of years (Trowler 2010). These surveys, the US National Survey of Student Engagement (NSSE) and the Australian Survey of Student Engagement (AUSSE), comprise self-rating questionnaires completed by students based on indicators of best practice: academic challenge; active and collaborative learning; student–faculty interaction; enriching educational experiences; supportive campus environment; and work-integrated learning (AUSSE only). However in this approach, using a survey method, the issue has become focused on what students are doing, and any assessment of students’ perceptions or expectations of their experience has been lost (Hand and Bryson 2008).

The term has traditionally been used less commonly in Europe and has been associated more with debates regarding student feedback, student representation and student approaches to learning (Trowler 2010). However, student engagement has been a significant part of education policy for a number of years. For example, student-centred learning in higher education ‘characterised by innovative methods of teaching that involve students as active participants in their own learning’ is a commitment of the European Higher Education Area (EHEA) Bologna Process (2012: 2). Indeed, one of the Bologna Process priorities for 2012–15 is to ‘Establish conditions that foster student-centred learning, innovative teaching methods and a supportive and inspiring working and learning environment, while continuing to involve students and staff in governance structures at all levels’ (EHEA 2012: 5).

In addition, recent research conducted into curriculum trends as part of the Medical Education in Europe (MEDINE2) project identified the empowerment of students to take responsibility for their own learning and student involvement in curriculum-planning committees as major current trends that it was hoped would develop further in the future (Kennedy et al. 2013).

While all agree that student engagement is important, there is considerable disagreement about what it means. As Kahu (2013) notes, ‘A key problem is a lack of distinction between the state of engagement, its antecedents and its consequences’ (2013: 758).

She identifies four relatively distinct approaches to engagement:

1 behavioural, which focuses on student behaviour and effective teaching practice;

2 psychological, which concerns the internal individual process of engagement, including behaviour, cognition, emotion and conation;

3 social-cultural, acknowledging the impact of the broader social, cultural and political context;

4 holistic, an approach which attempts to combine the strands together.

Others have drawn a distinction between market and developmental approaches to student engagement. The market model is based on neo-liberal thinking, identifies students as consumers and approaches engagement from a consumer rights and institutional market position. In contrast, the developmental model is based on a constructivist concept of learning and identifies students as partners in a learning community, emphasising student development and quality of learning (Higher Education Academy 2010: 3).

Each of the approaches to student engagement has strengths and limitations and Kahu (2013) presents a conceptual framework which seeks to combine all elements and present student engagement as, ‘A psycho-social process, influenced by institutional and personal factors, and embedded within a wider social context, [that] integrates the social-cultural perspective with the psychological and behavioural’ (2013: 768).

Benefits of student engagement

Engagement has been argued to hold many benefits for students, including a greater sense of ‘connectedness, affiliation and belonging’ (Bensimon 2009: xxii–xxiii); satisfaction with studies (Kuh et al. 2005); improvements in learning, cognitive development and critical thinking (Kuh 1995; Kuh et al. 2005); and improved grades (Tross et al. 2000). Research has suggested a strong link between academic and social engagement, with a sense of belonging aiding student learning (Bok 2006). There are many potential benefits to be gained by institutions, such as increased student retention (Kuh et al. 2008), reputational and quality assurance (Coates 2005). Medical education itself is also a potential beneficiary if student engagement in academic research and teaching is encouraged (McLean et al. 2013)

The rapidly changing nature of higher education and of students’ lives has led several authors to highlight the importance of the broader social, cultural and political context. Baron and Corbin (2012) note that, despite the policy push to adopt practices that enhance engagement, what is implemented is often fragmented and contradictory. They argue that, while student engagement is seen as positive by governments, universities and individual academics, many of their practices may have had the opposite effect. They highlight reduced support for student social activities, performance-oriented university cultures, larger class sizes and reduced contact time, in addition to the increasing marketisation of higher education and the shift in the perception of students to being consumers and commodities. Fundamental change in the relationship between students and institutions has led to renewed efforts by institutions to ensure students’ voices are heard and acted upon (Little et al. 2009).

The importance of student engagement in extracurricular activities and voluntary service has been highlighted. However, the demanding and intensive nature of medical school curricula can often leave little space for personal development and engagement within the academic community, and social isolation, burnout and depression are common among medical students (Bicket et al. 2010). In addition, the demands placed on students in their lives outside of studying have also been increasing. For example, James et al. (2010) reporting on research conducted in Australia note that, in 2009, 61 per cent of first-year full-time students were in paid employment of around 13 hours a week. The need to balance work and study is leading students to adopt a ‘time-savvy’ approach to learning, making calculated decisions about how best to use their time (Tarrant 2006).

Frameworks for engagement

Hand and Bryson (2008), following their review of student engagement, identified four important considerations for those wishing to enhance the student experience: the gap between staff and student expectations of who is responsible for engagement; the importance of establishing engagement (social and academic) early in university life; for significant gains it is important that an institutional approach is adopted; and engagement needs purpose: learning experiences that provide opportunities for autonomy, personal growth and change (Hand and Bryson 2008: 31).

A range of frameworks for measuring student engagement exist. The UK Quality Assurance Agency for Higher Education (QAA) highlights student engagement as relating to two core areas: improving student motivation to engage in learning and independent learning; and promoting student participation in quality assurance and enhancement processes (QAA 2012: 2). They note the positive influence student involvement can have on the development and delivery of all aspects of educational experience, from admissions and induction, through curriculum design and teaching delivery, to learning opportunities and assessment. The Quality Code (QAA 2012) highlights the requirement of higher-education providers to: ‘take deliberate steps to engage all students, individually and collectively, as partners in the assurance and enhancement of their educational experience’ (QAA 2012:12).

Seven indicators of sound practice are also identified: defining and promoting opportunities for any student to engage in educational enhancement and quality assurance; creating and maintaining an environment within which students and staff engage in discussions about demonstrable enhancement of the educational experience; arrangements for the effective representation of the collective student voice at all organisational levels; student representatives and staff having access to training and ongoing support to equip them to fulfil their roles in educational enhancement and quality assurance effectively; students and staff engaging in evidence-based discussions based on the mutual sharing of information; staff and students disseminating and jointly recognising the enhancements made to the student educational experience; and the effectiveness of student engagement being monitored and reviewed at least annually.

Student Participation in Quality Scotland (SPARQS), along with the key higher-education agencies in Scotland, have developed a framework for Scotland based on five key elements: students feeling part of a supportive institution; students engaging in their own learning; students working with their institution in shaping the direction of learning; formal mechanisms for quality and governance; and influencing the student experience at a national level. The framework also identifies six features of effective student engagement: a culture of engagement; students as partners; responding to diversity; valuing the student contribution; focus on enhancement and change; and appropriate resources and support (SPARQS 2012).

Operationalising student engagement

It is clear from the preceding discussion that student engagement can exist or be promoted at a number of levels. While ultimately it will occur at the level of the individual motivation to learn and engage in personal and professional development, there are a range of spheres in which universities and medical schools can seek to enhance the development of student engagement. The ASPIRE-to-Excellence in Medical Education initiative (www.aspire-to-excellence.org), in developing a set of assessment criteria for student engagement in medical schools, identified four spheres of student engagement: management of the medical school; provision of the medical school; research and the academic community; and local community and service delivery.

Each of these spheres represents a different context in which medical schools can support and promote social engagement. For example, student engagement in the management of a medical school could take the form of formal student involvement in the development of institutional or school mission or policy statements, accreditation processes or faculty development. The inclusion of the findings of student evaluations into teaching, learning and curriculum development, and the encouragement of students to engage in active learning, peer teaching and self and peer assessment are ways in which student engagement can be developed within medical school provision.

It is important to note that there is no blueprint for student engagement or threshold that must be attained before engagement can be said to be taking place. Rather, the format and extent of student engagement will differ within and between institutions. A more instructive way for assessing the development of student engagement is to see it as occurring along a spectrum, from a ‘traditional school’ characterised by low engagement to an ‘innovative school’ where engagement is high.

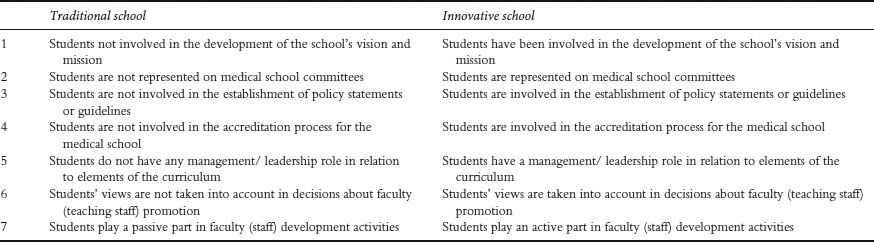

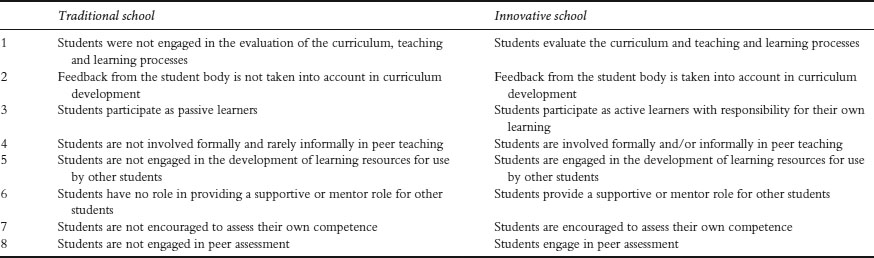

Table 7.1 Student engagement with the management of the medical school in traditional and innovative schools

Student engagement in the management of a medical school

As Baron and Corbin (2012) have argued,

Student engagement cannot be successfully pursued at the level of the individual teacher, school or faculty but must be pursued holistically in a ‘whole-of-university’ approach and with a common understanding of what it is the institution seeks to achieve.

(Baron and Corbin 2012: 760)

This could include involving students in the development of school mission and vision statements or any subsequent revisions that are made to underpinning values and commitments. Table 7.1 summarises a range of criteria for identifying student engagement in the management of a medical school, and how this would differ within a traditional and an innovative school.

While many schools have moved a long way from the ‘traditional’ end of this spectrum, with student representation on committees fairly common, some have suggested that student involvement can be tokenistic. The key to engagement is to ensure that involvement leads to action; that student voices are heard within mission statements and policy guidance, and that their views and experiences feed into faculty development and promotion. The case study from the University of Helsinki Medical Faculty, Finland demonstrates the widespread involvement of students in decision making at the institution, including within faculty promotion procedures.

Case study 7.1 Student engagement at the Faculty of Medicine in Helsinki

At the University of Helsinki Medical Faculty students are consistently engaged at all levels of development and decision making. There are about 40 student representative positions in more than ten different university bodies, ranging from the Student Selection Committee to the Committee for Evaluation of Teaching Skills, the Medical Library and the University Restaurant’s Committee. There are even student representatives at the highest level, with four of 18 members of the Faculty Council being students.

Student-centred learning methods dominate the learning encounters, most of which are organised in small groups, where interactions with both the teacher and peers are important. Within the Growing to be a Physician (GBP) studies spanning the 6 years of medical school, learning communication skills is supported by receiving and learning to give constructive feedback by teachers and peers. The ethics studies focus on hands-on ethical questions. The GBP track is a path to becoming a physician, a colleague and fellow learner in the world of continuous professional development.

During the first 2 years of medical school the primary method is problem-based learning (PBL), where also older students tutor younger ones. PBL evolves into case-based learning (CBL) during the clinical years. Starting from the third year students take histories and examine patients, presenting their findings to the clinical teacher and each other in a small group, learning together, and learning by doing, under close supervision by the clinician. Students have promoted active-learning environments such as skills labs, and self-directed learning by virtual patient pool (VPP), developed to enable students to practise diagnostic and treatment skills autonomously.

The students can start their practical training in the service system after the third year in specific training positions (junior amanuensis) under licensed physician supervision. After the fourth year they can practise as stand-in physicians during vacations, but only after having passed all courses of the first 4 years, and after the fifth year they can work in primary healthcare practices. The students get experience as practising physicians, responsible for the care of their own patients under senior physician supervision.

Professor applicants have their teaching portfolios reviewed by the Committee for the Evaluation of Teaching Skills, using an evaluation matrix. The University of Helsinki founded a Teachers’ Academy in 2013. Three teachers of the Faculty of Medicine were selected into the group of 30 founding members of the Academy. The applicants had to include a supportive statement from students in their application. The Academy will aim to improve the status of teaching in the academic community. By rewarding teachers, the university invests in students and the quality of learning.

A working group of the Medical Faculty is charged with the task of critically evaluating the present curriculum’s actual emphasis and volume. There are seven members, two of whom are students. The next step will be to update and improve the curriculum based on the evidence from the evaluation. Another group works on improving the 4-month real-life practising (amanuensis) processes and content. There are another two students involved, together with clinical teachers, primary care and local hospital workplace representatives.

It is important to engage students systematically, in the structures and in all improvement projects. There is always room to do things better. Students could become more actively involved also in provision of teaching, peer teaching and peer tutoring. Provision of iPads to all first-year students may pave the way to join forces in teaching and learning in the e-world, building on the real-world work that has been done.

Student engagement in medical school educational provision

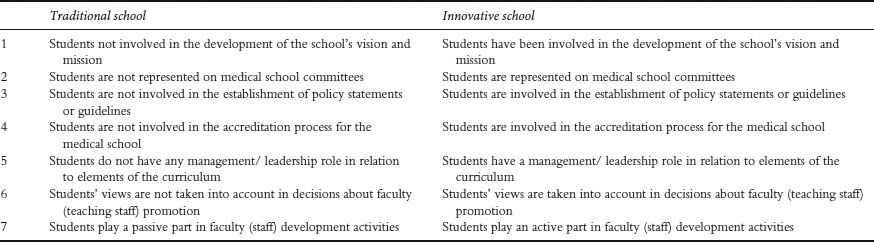

It is commonplace for students to fill in evaluation forms and surveys at the end of modules or years of study, but to what extent do schools act on the lessons held within them and adapt teaching and learning processes or revise the curriculum? Being able to see that their experiences and opinions are taken on board is essential to supporting student engagement. Engagement can also be fostered within a school’s teaching, learning and assessment processes through the development of active and self-directed learning initiatives and the skills for self-assessment. The involvement of students in peer mentoring, teaching and assessment has been shown to be highly beneficial for students’ own learning skills and development as well as increasing feelings of engagement (Yu et al. 2011; Nelson et al. 2013). Table 7.2 summarises a range of criteria for identifying student engagement in the educational provision of a medical school, and how this would differ within a traditional and an innovative school.

The case study from the University of Helsinki outlines a range of student-centred learning encounters, while the following case study from Slovenia demonstrates a success story of student-led initiative in peer tutoring.

Table 7.2 Student engagement in the provision of medical school education in traditional and innovative schools

Case study 7.2 Student involvement – from scratch, over self-sustainability, to the future, University of Maribor, Slovenia

In 2008 our medical school implemented a peer tutorial system (TS) initiative that had been developed by students. The student-driven project was associated with improved academic performance(Zdravkovic and Krajnc 2010)and its great success was further depicted in 2010 Senate conclusion: ‘We recommend our students to attend complementary education under peer tutors’ (PT) guidance’ (Krajnc and Kriz 2010).

We built on Topping’s (1996: 322) definition of peer-assisted learning (PAL), as ‘people from similar social groupings who are not professional teachers helping each other to learn and learning themselves by teaching’ and added an important ‘General’ component (G-PAL). This means that our PTs are not dedicated to a specific subject area but they give support for all subjects in Year 1 and Year 2 of studies. Moreover, they also offer general guidance about student life.

The non-compulsory G-PAL initiative began in 2008–9 with meetings based on three pillars: general guidance, core medical topic reinforcement and exam preparations. The implementation of these three pillars into practice was sequential and varied across tutoring groups. Initially, most groups focused on general guidance and core medical topics, for example, addressing the initial confusion in transition from secondary school to university, and motivating tutees for their learning.

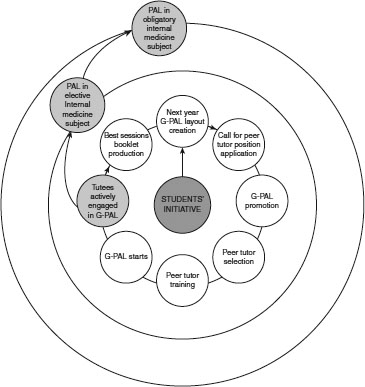

Figure 7.1 The process of self-sustainable general peer-assisted learning (G-PAL) evolution and two spin-offs continuing circular evolution similar to G-PAL.

Since 2010 our G-PAL has evolved to a more objective-based programme with exam preparations central to sessions. As shown in Figure 7.1, G-PAL evolution is linked to a vigorous PT selection process and intensive training before they start, i.e. PT development. Evidently, we implemented a self-sustainable system, as tutees engaged in G-PAL sessions were successfully recruited to become PT. Positive experiences were preserved in the G-PAL session booklet, containing remarks on session structure, content and teaching methodology.

A tripartite approach was used for G-PAL evaluation: the number of sessions and tutees’ attendance, next year’s advancement rates, and students’ feedback collected by a special student taskforce. Looking at some results in Year 1, there has been a shift in median number of session visits from three to nine in 1 year (despite G-PAL being non-obligatory), we observed an increase in students’ advancement rates to Year 2, and tutees increasingly reported being academically more successful due to G-PAL, from 46 to 73 per cent in a year (Zdravkovic and Krajnc 2010). In addition, student satisfaction with the peer tutor experience is demonstrated in the following examples of student feedback:

First-hand information about literature and exam experience have strongly affected my learning and improved my academic performance.

I find discussing learnt topics the best way to really master them.

An elective subject on propaedeutics was launched in 2010 based on PAL and utilising our simulation equipment, including the first undergraduate Objective Structured Clinical Examination (OSCE) in Slovenia (Zdravkovic et al. 2012). By including PT in the OSCE scoring, we foster peer assessment as an integral part of physician lifelong learning (Todorovic et al. 2012b). Finally, in 2012 we included PAL of clinical skills as an obligatory part of internal medicine with an OSCE before admitting students to clinical environment (Todorovic et al. 2012c).

As medical graduates should be able to ‘function effectively as a mentor and teacher’ (General Medical Council 2009: 27), emphasis should be given to peer teaching results and tutee benefits (Todorovic et al. 2012a; Zdravkovic and Zdravkovic 2012). In our experience, this positive feedback stemming from outcome-based teaching is the ultimate factor for continuous involvement in medical education, leading to state-of-the-art future medical educators.

For more information and our final report on TS implementation, visit the Center for Medical Education website at www.mf.uni-mb.si.

Student involvement in the academic community

Traditionally engagement in research and its dissemination, and participation in learned societies have been the preserve of faculty. However, the reduction in the number of doctors moving into academic medicine and medical education has become an area of concern. McLean et al. (2013) have suggested that providing students with opportunities to participate in research, become involved with the academic research community and present and publish their research has the potential to inspire student interest and reverse this trend. Additional benefits through involvement of students in these activities include communication and skills for lifelong learning. Table 7.3 summarises differences in student engagement in the academic community between traditional and innovative schools.

Table 7.3 Student engagement in the academic community in traditional and innovative schools

| Traditional school | Innovative school | |

| 1 | Students are not engaged in school research projects carried out by faculty members |

Students are engaged in school research projects carried out by faculty members |

| 2 | Students are not supported in their participation at local, regional or international medical and medical education meetings |

Students are supported in their participation at local, regional or international medical and medical education meetings |

Examples of the range of activities that can be promoted include involvement in the research work of faculty members, the development of student journals and conferences for disseminating their research findings.

Student engagement in the local community and service delivery

Student engagement activities can extend beyond the direct academic curriculum and be encouraged in relation to local communities and service delivery as well as extracurricular activities (Krause 2011). Students may become involved in local community projects or health services on a voluntary basis, as part of their studies or as employees. Extracurricular activities can provide an important means of integrating students into university life and fostering a sense of belonging, while the increasing globalisation of medicine means that students often desire and are encouraged to experience healthcare delivery in overseas electives. Table 7.4 summarises the differences in student engagement in local communities and service delivery between traditional and innovative schools.

The two following case studies demonstrate differing ways in which student engagement in the local community and understanding of social contexts can be developed. The College of Medicine, United Arab Emirates has introduced a team-based health promotion project for first-year medical students on a range of health topics to aid students’ understanding of local health issues and their impact on the community. The School of Medicine at Trinity College Dublin has sought to promote students’ awareness of global determinants of health through the curriculum, learning styles and opportunities for electives in developing countries.

Table 7.4 Student engagement in the local community and the service delivery in traditional and innovative schools

| Traditional school | Innovative school | |

| 1 | Students are not involved in local community projects |

Students are involved in local community projects |

| 2 | Students are not participating in the delivery of local healthcare services |

Students participate in the delivery of local healthcare services |

| 3 | Students are not participating in healthcare delivery during electives/attachments overseas |

Students participate in healthcare delivery during electives/attachments overseas |

| 4 | Students are not engaging with arranged extracurricular activities |

Students engage with arranged extracurricular activities |

Case study 7.3 Student mini-projects – celebrating World Health Day, United Arab Emirates

The College of Medicine at Gulf Medical University, Ajman, United Arab Emirates has adopted the organ system-based integrated curriculum for its MBBS programme since September 2008; this has provided the opportunity to introduce innovative trends in medical education, including teaching/learning methods. The programme has three phases: Phase I provides the foundation of the basic medical sciences and prepares the students for integrated learning during Phase II (organ systems) and Phase III (clerkships) of the curriculum. Multiple teaching/learning strategies and modes of assessment are employed in each phase. Mini-projects based on the themes of important world and international health days recognised by the World Health Organization are conducted during Phase I, or the first year in medical school.

The mini-project, an activity that is entirely a student initiative, seeks to maximise student engagement by combining fun with learning during the first year of medical school. At the start of each academic year, all 70 newly admitted medical students in groups of five are allotted mini-projects by draw of lots. Each group is assigned a faculty supervisor to monitor their progress. The theme of each project signifies a world health or international health day. The aim of the mini-project is to make students understand the clinical, social, psychological and preventive aspects of a health day, make them work in teams and improve their communication and presentation skills. Each group elects a leader who guides and coordinates the group activities. Enough time is given to students to prepare the projects. Frequent meetings are held by the groups towards preparation of the project. The minutes of all meetings are recorded and submitted to the faculty supervisor for guidance and advice.

The projects are presented by the group on the specific world or international health day in two parts to all other students, faculty and invited guests. The first part is conducted in the college foyer and activities include quizzes, skits, role playing and games to convey the message of the health day. Brochures containing general information about the health day are distributed to the other students and staff of the college as part of health education. The second part is usually an interactive session conducted in the college auditorium using PowerPoint slides with activities such as games, models, charts and images.

The students are assessed for the content of the project and their presentation skills. A faculty supervisor assesses the group for the teamwork. Peer and self-evaluation and reflections form part of the assessment. The knowledge and awareness about the psychosocial and preventive aspects of major health problems covered in the mini-projects are assessed in the summative examinations.

The major health days covered in an academic year include World Elder’s Day, World Mental Health Day and World Arthritis Day in October; World Diabetes Day and Universal Children’s Day in November; World AIDS Day and International Day of Persons with Disabilities in December; World Kidney Day in March; World Haemophilia Day and World Malaria Day in April; Thalassaemia Day and World ‘No Smoking’ Day in the month of May.

Carrying out these mini-projects has provided first-year medical students with an important and early experience of common diseases in the community and their impact on health and society, and given them an opportunity to learn about prevention, combining fun with learning. Analyses of peer, self and faculty evaluations show that the mini-projects have helped students in gaining knowledge about common diseases, encouraged them to work as teams and prepared them to conduct research projects in subsequent phases.

Case study 7.4 Engaging students to take a global view of healthcare through the global determinants of health and development course in Trinity College Dublin

The School of Medicine, Trinity College Dublin, Ireland was founded in 1711. In the academic year 2012–13 there were 756 students registered in the 5-year undergraduate programme. The School aims to educate graduates recognisable by their unique qualities of scholarship, engagement and innovation that are responsive to the needs and health problems of society nationally and internationally. A need for global health education was acknowledged and resulted in the introduction of the Global Determinants of Health and Development (GDH&D) course in the medical curriculum in 2009. This course aims to develop students’ understanding of emerging health issues in Ireland and their relationship with global health issues and international development (Skillshare International Ireland 2013).

The course is a compulsory component of the advanced clinical and professional practice module in Year 3. Students build on their existing knowledge and experience within this intensive course which is scheduled to enable ongoing engagement. The week-long conference-style format incorporates a series of keynote, plenary speeches and small-group workshops that facilitate discussion, debate and active participation. Experts with practical field experience lead sessions based on a theme exploring the cultural, social, legal, political and economic dimensions of complex healthcare systems.

Assessment methods include an individual reflective essay and group poster presentation. A pre-course attitudinal questionnaire captures student attitudes to various issues and changes in attitudes are recorded in post-course questionnaires. Evidence of changes in student attitudes as a result of attending this course has been indicated in areas such as health worker migration, education and climate change (Hastings et al. 2012).

Analysis of a sample of students’ reflective essays in 2010 reveals a better understanding of the relationships between poverty, development and its impact on health by a large majority of students following the course. One-fifth expressed an intention to engage with healthcare actively in developing countries (Pardinaz-Solis et al. unpublished).

One-third of students in Years 3 and 4 choose to go to developing countries for summer elective with the Medical Overseas Voluntary Electives (MOVE) charity. This may indicate ongoing engagement with the course. MOVE is organised and managed by Year 4 students with the support of the school. In 2013, Year 3 students organised their own clinical skills workshops within Global Health Week to teach second-level students and raised funds for MOVE.

Short courses can have an impact far beyond initial student contact. Courses that encourage active participation and reflection and provide opportunities for further engagement can create a platform for students to take forward their learning into committed action. As curriculum designers and medical educators, we should endeavour to be responsive to emerging needs and flexible in the approach to course design, delivery and assessment. Such an approach models the attributes we encourage in our students.

Summary

Many changes have taken place within medical education globally in recent decades that have impacted on the role of students, their relationship to the curriculum and their institution. Student engagement is now widely seen as important at all levels, from the individual student, through the institution to the wider community. Increasingly, the focus of teaching and learning has shifted to become more student-centred, with an emphasis on promoting active and self-directed learning. In addition there has been a renewed focus on the ability of the student voice to be included within the management of organisations and the design of curriculum. A range of frameworks are available offering guidance on operationalising student engagement, including the work of the ASPIRE-to-Excellence Initiative (www.aspire-to-excellence.org).

• Student engagement offers the potential of improvements to learning, cognitive development, student retention, quality assurance and a sense of belonging.

• Changes to students’ role need to be reflected in all aspects of medical education.

• Student engagement requires a holistic approach, involving the whole of the university.

• Policy changes to support engagement need to be cohesive and consistent, not fragmented and contradictory.

• Initiatives require strong institutional and financial support.

• Peer-led initiatives, including in teaching and learning offer excellent opportunities for enhancing social engagement.

• Extracurricular, social and community initiatives are as important as academic ones in fostering a sense of belonging.

Bibliography

ASPIRE (2014). Online. Available HTTP: http:www.aspire-to-excellence.org (accessed 8 September 2014).

Baron, P. and Corbin, L. (2012) ‘Student engagement: Rhetoric and reality’, Higher Education Research and Development, 31(6): 759–72.

Bensimon, E.M. (2009) ‘Forward’. In S.R. Harper and S.J. Quaye (eds) Student engagement in higher education. London: Routledge.

Bicket, M., Misra, S., Wright, S.M. and Shohet, R. (2010) ‘Medical student engagement and leadership within a new learning community’, BMC Medical Education, 10: 20.

Bok, D. (2006) Our underachieving colleges: A candid look at how students learn and why they should be learning more, Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Coates, H. (2005) ‘The value of student engagement for higher education quality assurance’, Quality in Higher Education, 11(1): 25–36.

EHEA Ministerial Conference (2012) Making the most of our potential: Consolidating the European higher education area. Bucharest communique, Bucharest: European Higher Education Area.

General Medical Council (2009) Tomorrow’s doctors: Outcomes and standards for undergraduate medical education. London: General Medical Council. Online. Available HTTP: http://www.gmc-uk.org/Tomorrow_s_Doctors_0414.pdf_48905759.pdf, p. 27 (accessed 20 November 2014).

Hand, L. and Bryson, C. (2008) Student engagement, London: Staff and Educational Development Association (SEDA).

Hastings, A., Pardiñaz-Solis, R., Phillips, M. and Hennessy, M. (2012) ‘Measuring attitude change in medical students: Lessons from a short course on global health’, Medical Education Development, 2(1): 1–4.

Higher Education Academy (2010) Framework for action: Enhancing student engagement at the institutional level, York: Higher Education Academy (HEA).

James, R., Krause, K.-L. and Jennings, C. (2010) The first-year experience in Australian universities: Findings from 1994–2009, Melbourne, Australia: Centre for the Study of Higher Education.

Kahu, E.R. (2013) ‘Framing student engagement in higher education’, Studies in Higher Education, 38(5): 758–73.

Kennedy, C., Lilley, P., Kiss, L., Littvay, L. and Harden, R.M. (2013) Curriculum trends in medical education in Europe in the 21st century, Dundee: AMEE/MEDINE2.

Krajnc, I. and Kriz, B. (2010) Minutes from the 15th Regular Senate meeting at Faculty of Medicine University of Maribor: Conclusion 52. 19 April 2010.

Krause, K.L.D. (2011) ‘Transforming the learning experience to engage students’, in L. Thomas and M. Tight (eds) Institutional transformation to engage a diverse student body. International perspectives on higher education research, volume 6, Bingley: Emerald Group.

Kuh, G.D. (1995) ‘The other curriculum: Out-of-class experiences associated with student learning and personal development’, Journal of Higher Education, 66(2): 123–55.

Kuh, G.D., Kinzie, J., Schuh, J.H. and Whitt, E.J. (2005) ‘Never let it rest: Lessons about student success from high-performing colleges and universities’, Change: The Magazine of Higher Learning, 37(4): 44–51.

Kuh, G.D., Cruce, T.M., Shoup, R., Kinzie, J. and Gonyea, R.M. (2008) ‘Unmasking the effects of student engagement on first year college grades and persistence’, Journal of Higher Education, 79(5): 540–63.

Little, B., Locke, W., Scesca, A. and Williams, R. (2009) Report to HEFCE on student engagement, Centre for Higher Education Research and Information. http://www.open.ac.uk/cheri/documents/student-engagement-report.pdf (accessed 27 September 2013).

McLean, A.L., Saunders, C., Velu, P.P., Iredale, J., Hor, K. and Russell, C.D. (2013) ‘Twelve tips for teachers to encourage student engagement in academic medicine’, Medical Teacher, 35(7): 549–54.

Nelson, A.J., Nelson, S.V., Linn, A.M.J., Raw, L.E., Kildea, H.B. and Tonkin, A.L. (2013) ‘Tomorrow’s educators . . . today? Implementing near-peer teaching for medical students’, Medical Teacher, 35(2): 156–9.

Pardinaz-Solis, R., Newell-Jones, K., Hastings, A. and Phillips, M. (Unpublished) Learning global health: Impact on student after a short course in global health and development.

Quality Assurance Agency for Higher Education (QAA) (2012) UK quality code for higher education. Part B: Chapter B5: Student engagement, Gloucester: QAA.

Skillshare International Ireland (2013) Global determinants of health and development course. Online. Available HTTP: http://www.skillshare.ie/developmentawareness/gdhd.html (accessed 22 March 2013).

Students Participation in Quality Scotland (SPARQS) (2012) A student engagement framework for Scotland, Edinburgh: SPARQS. Online. Available HTTP: http://www.sparqs.ac.uk/upfiles/SEFScotland.pdf (accessed 1 October 2013).

Tarrant, J. (2006) ‘Teaching time-savvy law students’, James Cook University Law Review, 13: 64–80.

Todorovic, T., Pivec, N., Fluher, J. and Bevc, S. (2012a) ‘Long-term clinical skills retention rate in peer teaching’, short lecture given at VII. SkillsLab Symposium, Marburg, March.

Todorovic, T., Pivec, N., Hojs, N., Zorman, T. and Bevc, S. (2012b) ‘Who should evaluate at OSCE stations?’, Poster presented at Society in Europe for Simulation Applied to Medicine Annual Conference, Stavanger, June.

Todorovic, T., Zdravkovic, M. and Zeme, K. (2012c) ‘Peer tutors guide: Peer teaching in Simulation Centre at Faculty of Medicine University of Maribor: Academic year 2012/2013 (original Slovenian title: Prirocˇnik za tutorje: tutorstvo v Simulacijskem centru Medicinske fakultete Univerze v Mariboru: študijsko leto 2012/2013.)’, Maribor, September.

Topping, K.J. (1996) ‘The effectiveness of peer tutoring in further and higher education: A typology and review of the literature’, Higher Education, 32(3): 321–45.

Tross, S.A., Harper, J.P., Osherr, L.W. and Kneidinger, L.M. (2000) ‘Not just the usual cast of characteristics: Using personality to predict college performance and retention’, Journal of College Student Development, 41(3): 325–36.

Trowler, V. (2010) Student engagement literature review, York: HEA.

Yu, T.C., Wilson, N.C., Singh, P.P., Lemanu, D.P., Hawke, S.J. and Hill, A.G. (2011) ‘Medical-students-as-teachers: A systematic review of peer-assisted teaching during medical school’, Advances in Medical Education Practice, June 23(2): 157–72.

Zdravkovic, M. and Krajnc, I. (2010) ‘Peer assisted learning improves academic success’, poster presented at International Association for Medical Education Annual Conference, Glasgow, September. Online. Available HTTP: http://amee.org/getattachment/Conferences/AMEE-Past-Conferences/AMEE-Conference-2010/AMEE-2010-Abstract-book.pdf, p. 180-1 (accessed 20 November 2014).

Zdravkovic, B. and Zdravkovic, M. (2012) ‘DREEMing in Slovenia: Peer versus faculty teaching in light of average grade’, short communication presented at International Association for Medical Education Annual Conference, Lyon, August. Online. Available HTTP: http://amee.org/getattachment/Conferences/AMEE-Past-Conferences/AMEE-Conference-2012/AMEE-2012-ABSTRACT-BOOK.pdf, p. 337-8 (accessed 20 November 2014).

Zdravkovic, M., Todorovic, T. and Bevc, S. (2012) ‘Following global trends in medical education: Objective structured clinical examination (original Slovenian title: Na sledi svetovnim trendom izobraževanja v medicini: Objektivni strukturiran klinicˇni izpit.)’, ISIS, 21(11): 74–9. Online. Available HTTP: http://issuu.com/visart.studio/docs/isis2012-11-brezoglasov/74?mode=window&viewMode=doublePage (accessed 30 March 2013).