AUTHENTIC LEARNING IN HEALTH PROFESSIONS EDUCATION

Problem-based learning, team-based learning, task-based learning, case-based learning and the blend

Medical schools around the world have moved towards more interactive learning situations using problems scenarios and cases.

‘Authentic’ has been defined as ‘genuine, real and worthy of trust’ by www.freeonlinedictionary.com and ‘learning’ has been described as measurable and relatively permanent change in behaviour through experience, instruction or study by www.businessdictionary.com.

A deeper definition of ‘authentic learning’ is ‘when the learning is integrally related to the understanding and complex solutions of real life complex problems’ (Lombardi and Oblinger 2007). Lave and Wenger (1991) argue that all learning, in any discipline or profession, needs to be ‘enculturated’ into the discipline, and the earlier the better. Educational researchers have described the key features of authentic learning experiences in ten design elements (Von Glasersfeld 1989), which can be adapted to any discipline. These could be further clustered under four main key features:

1 real-world relevance – activities matching professional practice as near as possible, e.g. high-fidelity simulation;

2 challenging problems – around and within which learning takes place. These activities require investigation and inquiry by students over a period of time and synthesis from multiple resources;

3 collaborative activities – among learners and reflection about their learning;

4 interdisciplinary perspectives – integrated curricula and assessment.

Students in the early phases of authentic learning environments and activities therein may be disoriented or even frustrated with this new experience. This may have more to do with their prior learning experiences and development rather than preference for more or less passive learning approaches. However, this changes when problems, tasks and activities are relevant to what really counts in real life (Herrington et al. 2003). Authentic learning privileges the ‘messiness’ of real-life decision making, where there are no completely right or wrong answers and all depends on the context and what is fit for purpose. This requires considerable reflective judgement that goes well beyond the memorisation of content (Dede et al. 2005). In this chapter, examples of authentic learning practices used in health professional education (HPE) are described.

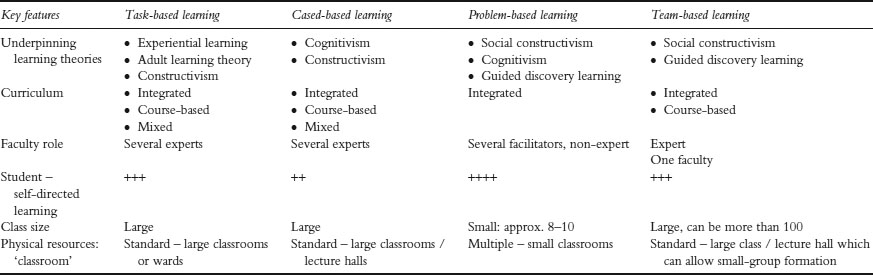

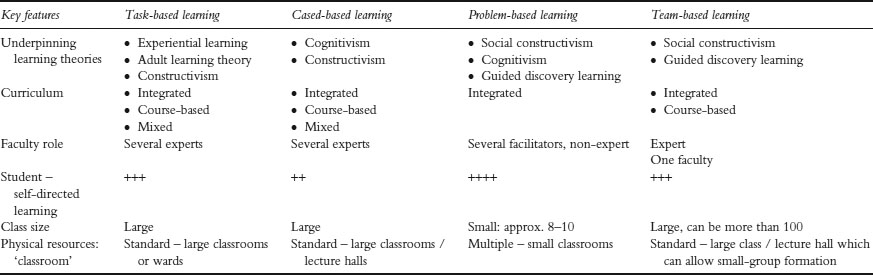

Table 10.1 Comparing key features of four authentic learning methods

If we apply these definitions to the context of HPE, authentic learning should be relevant, closely linked to the future profession of the learner and lead to relatively permanent change in the learner’s behaviour by demonstrating competence considered essential for the job. To achieve these outcomes, educational strategies should be different from the traditional teacher-centred didactic teaching. Adult students prefer to learn by doing rather than listening (Knowles 1980; Taylor and Hamdy 2013). During the last three decades, HPE has focused more on outcome competencies, ‘what the graduate is able to do’ rather than ‘how much s/he knows’. This goal influenced the move towards designing and implementing outcome-based, competency-based curricula (Harden et al. 1999). This trend necessitates the implementation of authentic learning and relevant teaching strategies, student assessment and programme evaluation systems and methods. More and more institutions have moved towards interactive learning situations using small groups, student-centred learning, integrated curricula, the early introduction of clinical sciences and skills and the creation of more realistic and authentic settings for learning. Authentic learning cuts across disciplines and brings students into meaningful contact with the real world, future work environment and patients.

This chapter focuses on the key features, theories and principles underpinning authentic learning; the application of strategies in different contexts and phases of the curriculum; and implementation problems that can lead to failure in achieving its objectives. It is not intended to provide a comprehensive review of the different types of authentic learning. Rather, four common strategies supportive of student-centred learning will be presented, discussed and compared:

1 problem-based learning (PBL);

2 team-based learning (TBL);

3 task-based learning (TkBL); and

4 case-based learning (CBL).

In addition, case studies are presented with messages applicable in multiple contexts. The key elements of each of these teaching approaches are summarised in Table 10.1.

Educational theories underpinning authentic learning

The four learning strategies highlighted above derive from different contemporary learning theories.

Behavioural theory

Behavioural theories emphasise the stimulus that can be a problem/case scenario, a task or an encounter with a real patient. The reaction ‘behaviour’ of the learner to the stimulus is influenced by the context and the history of those involved. Feedback and reinforcement are important to support and inculcate the behaviour and for it to become a ‘habit’ (Schmidt 1993).

Cognitive theory looks at authentic learning activities that promote critical thinking, reasoning processes and particular mechanisms of processing, storing and retrieving new information (Dolmans et al. 2002).

Constructivist theory

Constructivist theory is a philosophical view on how we come to understand or know (Von Glasersfeld 1989; Rorty 1991). As a theory and philosophical perspective of modern education, it is characterised by:

• Understandings developed from interactions with the environment. What is learned is not separate from how it is learned and the context in which it is learned.

• The goal of the learner is central in considering what is learned.

• The learner builds and constructs understanding based on prior experiences and knowledge.

• The social environment is critical to the development of knowledge and understanding (Von Glasersfeld 1989). Collaborative learning, as in PBL and TBL, fits with constructivism. They test students’ understanding about a problem, compare it with others’, expand it and facilitate its storage in deep memory and its retrieval. This proposition is also similar to the cognitive perspective.

• Reflection on and in action, together with the role of the teacher in providing support, is thought to provide a scaffold on which the student can build learning.

Experiential learning theories

Experiential learning theories (Kolb 1984) and social constructivism (Schon 1983) are closely related to PBL, TBL and TkBL. Experiential learning relates to learning professional tasks in the work environment. Students at an early or advanced phase of their learning link experience with learning of knowledge, skills and attitude, emphasising relevance. Knowledge, if not applied, is quickly forgotten. The teacher’s role in social constructivism is one of facilitating learning rather than providing information. The teacher values and challenges the learner’s thinking. The concept of the learning scaffold and the zone of proximal development (Vygotsky 1978) represent the role of the teacher and the teacher’s interaction with the student, attempting to extend the student’s development into the gap between the learner and teacher.

Social theories of learning

Social theories of learning (Bandura 1977) emphasise the importance of learning from each other and creating a community of learners. Ideas are discussed, elaborated and challenged by teams and group of learners. Social media and electronic communication networks are examples of this principle. The social perspective supports students’ and teachers’ reflection on content, process and the learning experience itself, all of which need training for students to develop this skill, do it well and record it (reflective portfolio). Teachers require the ability to guide students, evaluate the reflective portfolio and give and receive timely constructive feedback.

PBL is an approach that emphasises students’ active and self-directed learning individually and in small groups. It was introduced into medical education in the late 1960s at McMaster University, Canada (Barrows 1986) and rapidly spread all over the world to become a symbol of innovation. It was a response to the perceived lack of relevance in the early years of medical education and was a break from the existing focus of teacher-centred, passive student role that emphasised how much students knew and could recall rather than the relationships among things. It is characterised by small groups of students (six to ten) who worked around a problem to seek to understand its different facets. The main outcome is learning from the problem, not solving the problem. The tutor’s role is to facilitate group learning activities rather than to be a primary source of information. Typically, the curriculum design of PBL is the integrated, organ system in which students study a new problem each week. Problems have different learning objectives related to basic medical sciences, clinical sciences and behavioural sciences. Two to three tutorial sessions of small-group learning typically take place each week.

The roles of students and the tutor in PBL have been well described (Schmidt 1993; Barrows 1996; Dolmans et al. 2002). What happens in the first tutorial session of a new problem and the second tutorial session (the reporting phase) have also been well described (Schmidt 1993). On the other hand, what students and the programme provide in between and beyond the sessions is vague. Other structured educational activities arranged by the programme vary and may include lectures, resource sessions, review sessions, laboratory work, clinical skills and more. This blend of educational strategies and instructional methods characterises PBL as implemented in the first decade of the 21st century.

Over the last four decades, hundreds of studies have described, analysed and evaluated PBL (Maudsley 1999). The way PBL is implemented varies widely from ‘window dressing’ to an orthodox implementation, as originally described in the 1960s, i.e. no lectures. The fuzzy world of PBL (Hamdy 2008) requires attention and flexibility in relation to the context of implementation while at the same time being vigilant in maintaining key principles, values, objectives and rationale.

It is common to see PBL programmes become inattentive to some of the underlying assumptions that make it work best. This is one of the most common and important problems encountered by PBL programmes internationally. The case study of the Faculty of Medicine, Suez Canal University, Egypt, illustrates how one institution adjusted its PBL programme to maintain its viability.

Case study 10.1 Implementation of computer-assisted PBL sessions to medical students at Faculty of Medicine, Suez Canal University, Egypt

The Faculty of Medicine Suez Canal University (FOM-SCU) adopted PBL as one of its main learning strategies from its inception in 1978. We started to replace the paper-based educational problems with interactive digital problems in 2009 in order to motivate students and increase engagement in the learning process. The newly designed problems were enriched by multimedia to improve the learning environment and to increase the opportunity for more diverse elaboration of learning, connecting their knowledge and analytical thinking skills. Students see images and video clips and hear sounds of the relevant clinical manifestations of the patient problem during discussions. The underlying assumption was that this would improve the diversity of their learning experiences and enhance their understanding of the case while at the same time providing better learning.

Student satisfaction was assessed at the end of the first year of implementation. Questions addressed various aspects of the learning process, such as brainstorming, knowledge acquisition and the impact on their assessment. A total of 175 of 330 students responded to the questionnaire. Analysis showed that students believed that e-problems helped them to understand better (79 per cent), participate more in discussions (70 per cent), render PBL sessions more interesting (79 per cent), focus their discussion (63 per cent) and improve their achievement in problem solving (49 per cent) and written exams (39 per cent). Analysis of the open-ended comments showed that students asked for more multimedia and less text (36 per cent) and more training for tutors on how to facilitate e-problem discussions (12 per cent). The analysis of tutor responses showed that e-problems helped students to understand better (83 per cent), participate more in discussions (83 per cent) and render PBL sessions more interesting (83 per cent) and focused (50 per cent).

The second phase of the project began in 2011 by adding digital problems to the clerkship phase. Here the aim was to improve clinical reasoning skills. This was done by presenting students with a video tape of a simulated patient encounter interrupted by pause intervals to trigger reflection. A similar assessment of this phase of the project showed that 84 per cent of the students agreed that e-format was better than the conventional paper format and 80 per cent believed that it improved their clinical reasoning skills.

PBL, in most medical colleges, is implemented mainly in the pre-clerkship phase of the curriculum and disappears in the clerkship phase. To avoid this disconnection, the written scenario, ‘The Problem’, is replaced by a real patient problem while maintaining the small-group learning structure.

Initially, as students learn to use PBL, there is a high degree of uncertainty about the depth and breadth of study required and expected. As the tutorial sessions unfold, students can compare and contrast what they have studied and learned and the extent to which it is similar and different to what other students have done. A broad overview of the ‘block/unit’ objectives and a tutor guide can help both students and tutors ameliorate this problem of uncertainty of depth and breadth of learning.

Another problem is a tendency of students to regress to discipline-focus thinking. For example, it is not uncommon for students, during the first tutorial session of a new problem, to split the problem into discipline-related objectives and forget about the problem scenario and how new information relates to the findings and presentation of the problem.

Students are advised that they are responsible for all the objectives generated from the problem (Dolmans et al. 2005). In PBL, the development of a concept map is another mechanism which has been effective in ameliorating this problem (Kassab and Hussain 2010), as it can illustrate the relationships between the different concepts and disciplines.

Assessment and learning are inseparable. In PBL, if the assessment is not in alignment with the learning objectives derived from the problems and the process as a whole related to PBL, the learning strategy may fail. The case study from the Arabian Gulf University in Bahrain is a good illustration of this. They addressed this problem through adjusting the assessment to promote integration.

Case study 10.2 Integrated assessment in problem-based learning promotes integrated learning

PBL has become increasingly popular in medical education over the past four decades. There are strong educational reasons for this. It is worthwhile stepping back and considering the extent to which the many different forms of PBL practised in schools do, in fact, take advantage of the educational benefits of this strategy to promote authentic learning.

The College of Medicine and Health Sciences in the Arabian Gulf University in Bahrain has practised PBL in its undergraduate medical curriculum since its inception in 1982. Almost two decades later it became evident that a practice that tended to detract from the authentic characteristics of PBL was occurring in many student groups during the pre-clerkship phase of the curriculum. For example, during the first meeting for a given problem, discussion of the sequence of triggers, which should have formed the basis by which learning needs were identified, quickly focused on the disciplines which impinged on the problem. Each discipline was considered separately by the group and students allocated responsibility amongst themselves to learn according to discipline. Returning after a period of self-study for the second meeting, students shared their learning by discussing each discipline in turn. Individual students were often unaware of related concepts from other disciplines. Integrated learning, one of the main advantages of PBL, was becoming disintegrated. Instead, the problem was seen as a summation of concepts from different disciplines, rather than a whole formed by the relationships among the concepts.

A closer examination of this undesirable practice showed that it was, in part, related to the nature of student assessment. Examinations took place at the end of each organ system, and sometimes after combinations of organ systems, as well as at the end of the pre-clerkship phase. These examinations purported to be ‘integrated’. However, they consisted of a collection of test items constructed by individual departments/disciplines. Students know how to survive and play the education game. They resorted to a learning strategy that addressed their immediate concerns, i.e. negotiating the impending examination successfully. Each examination consisted of a multiple-choice question (MCQ) paper, a short-answer question (SAQ) paper and an Objective Structured Practical Examination (OSPE). Students preferred to learn discipline-wise rather than to use the problems to integrate their learning among different disciplines. They did what the teachers asked them to do in the examinations.

A decision was made to make the SAQ paper integrated. Themes were identified within each organ system module and assigned to each assessment committee member for that module. A skeleton of an SAQ was drafted by a member of an interdisciplinary subcommittee consisting of representatives from disciplines related to that theme. Each subcommittee member added ‘flesh’ to the related part of the question. At a subsequent meeting, links between the parts were sought and deliberate attempts made to test the interdisciplinary links within the theme. The question was then submitted to the assessment committee for further discussion and clarification before being accepted into a bank of questions from which the SAQ part of the examination was set.

While a study has not been undertaken since this system was adopted in the school, students self-study differently, in a more integrated manner.

It must be recognised by schools wanting to introduce PBL that it is a strategy to achieve desirable learning habits and relevant outcomes among students, rather than an end in itself. In this sense, it is similar to cadaver dissection in anatomy, and clinical skills training, both a means to an outcome rather than the outcome itself. The same applies to all the other methods of authentic learning outlined in this chapter. The practice of a method by itself should not be the determinant of authenticity. Rather it should be the effect the method has on student learning in preparation for practice in the real world of medicine.

Unsubstantiated claims have been made that PBL is more expensive than subject-based learning or other learning strategies in which large numbers of students are taught in a class with one faculty. These claims are contradicted by studies that have demonstrated that, up to a class size of 100 students, PBL is not more expensive (Mennin and Martinez-Burrola 1986; Hamdy and Agamy 2011). PBL does, however, require a different set of skills, commitment and preparation.

Class size and infrastructure make a difference when implementing and sustaining PBL programmes. Sudden increases in class size, often as an attempt to meet increased demands from the healthcare system, can disrupt the underlying assumptions and practices of the tutorial, as seen in the following case study from the Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences, Universiti Malaysia Sarawak, Malaysia.

Case study 10.3 Authentic learning via problem-based learning –reflections from a Malaysian medical school

The medical school at the Universiti Malaysia Sarawak (UNIMAS) became the second in Malaysia to employ a PBL curriculum upon its inception in 1995 (Malik and Malik 2002a). The continuing challenge in UNIMAS is to implement PBL in ways that enable students to benefit maximally from its educational philosophy. In the initial years of the school’s inception all teachers were trained as tutors. They sat in all the lectures and guided their respective PBL groups. The assessments they designed tested the entire taught curriculum. However, as the school was directed to increase its student intake continually, teachers were continuously recruited. Most came from schools with lecture-based curricula, where it was assumed students learned mainly by transfer of information via lectures (Margetson 1997).

After the fifth year, when the school had the full complement of Phase One and Phase Two students, teaching in Phase One and PBL tutorials were handled almost exclusively by pre-clinical teachers while specialist clinicians taught mainly in Phase Two. Phase One lecturers no longer attended each other’s lectures and only knew the PBL teaching content in the few blocks in which they tutored. Hence their assessment questions mainly tested the content of their own lectures. Over-recruitment of teachers in a particular discipline resulted in the creation of new teacher-centred lectures in that discipline. Consequently, time for self-directed learning was progressively reduced (Malik and Malik 2002b) and information from lectures frequently duplicated PBL content. Without the services of a medical education specialist, tutor training sessions were irregular and PBL case review became infrequent. Tutor training focused mostly on the steps of PBL, without its underpinning pedagogical principles. When student numbers outgrew tutors, PBL group size increased up to 13 students per group.

To improve this situation, a PBL coordinator was appointed, tutoring of one trigger was accorded the same workload value as giving a lecture, tutor training was conducted regularly and incorporated the PBL philosophy, PBL rooms were uniformly equipped, student training in PBL increased, the PBL group sizes reduced and the PBL scenarios were reviewed.

The successful implementation of PBL requires suitable infrastructure for tutorials, regular training of faculty and students and constant review. At the UNIMAS medical school the challenge is now to harmonise the lecture and PBL content so that authentic learning prompted by real-world problems is underpinned by appropriate and complementary teaching with balanced assessment.

The take-home message is that PBL, like any educational work, requires continuous attention and multiple small adjustments on a regular basis. Failing to do this leads to much more difficult and expensive problems that are avoidable.

Team-based learning

TBL is a strategy for teaching and learning first described by Larry Michaelsen for business education (Michaelsen et al. 2002) and later introduced to HPE (Seidel and Richards 2001; Hunt et al. 2003; Parmelee and Hudes 2012). Embedded in this approach is the ability to be a critical thinker and work effectively in a team. TBL is a ‘guided discovery learning’ model. Social constructivist theory (Savery and Duffy 1995) constitutes the main theoretical framework of TBL. Three phases are typically described for TBL:

1 Phase One – ‘Pre-class study’ in which students prepare for class by going through the objectives and pre-class assignments assigned in advance by the teacher.

2 Phase Two – This starts with an Individual Readiness Assurance Test (IRAT). Students answer individually a number of questions, usually MCQs. Next, the same test is discussed in small groups, the Group Readiness Assurance Test (GRAT). The elaboration and collaboration to find the best answer and problem solution create an interactive learning environment. Faculty members direct the session, provide feedback and wrap up at the end.

3 Phase Three – This is the application phase, where groups work on another problem that encourages them to apply their newly acquired knowledge to solve another similar problem. This can take place during the same session, if time allows, or in a separate session.

TBL has the advantage of cost-effectiveness, as large numbers of students can be in one classroom, and it fits well with a subject- or course-based curriculum. The teacher is a subject matter expert whose role changes from purely that of an information giver to one that includes planning and facilitating learning. Students are active as learners before, during and after the class session. TBL can also be combined with other teaching methods, lecture-based and even PBL (Abdelkhalek et al. 2010; Anwar et al. 2012).

The ‘flipped classroom’ (McLaughlin et al. 2014) is a buzzword which is spreading at all levels of education – primary, secondary and higher. It is an active learning strategy coupled with advancements in instructional technology like video-taping lectures, use of social media and others. Learning is student-centred, before coming to the class, in the classroom and beyond. The flipped classroom has many features of TBL in that learning takes place before coming to the classroom and the in-class activities are explanations and applications of the pre-class-acquired knowledge. The initial testing of students’ preparedness is similar to the IRAT of TBL. It increases the student’s commitment to study and prepare before coming to the class. The in-class small-group activities and discussion in a flipped classroom are close to the GRAT. In the two approaches, the role of the teacher changes from provider of information to facilitator of learning.

Case study 10.4 The effect of team-based learning on students’ learning in a basic science course at the Universidad Peruana de Ciencias Aplicadas Medical School

The School of Medicine of the Universidad Peruana de Ciencias Aplicadas (UPC-MS) was founded 7 years ago in Lima, Peru and based its curriculum planning on Harden’s spiral curriculum model, using PBL as the integrating axis (Harden et al. 1997). Prior to implementing a PBL methodology, it was decided to use TBL as a transition from working in large groups to small groups.

A curriculum change in 2010 provided an opportunity to study the benefits of implementing TBL with students studying biology. TBL sessions were offered in the curriculum in the second semester. They were developed in three sessions of 4 hours per week, with a facilitator-to-student ratio of 2:30 per classroom. The structure of TBL consisted of:

• first session, reading or viewing a video about a biology topic, then concluding the session with a reading test;

• second session, individual and group assessment (multiple-choice tests that are discussed at the end of the training session);

• third session, case solution (clinical cases are presented about some topics developed in the biology course).

Case study resources included biology class material, reference texts and the internet. The results were better performance on tests in the group exposed to TBL. Teacher training in TBL was an important factor, which should always be considered.

Task-based learning

TkBL is an approach in which learning is built around a specified task. Learning results from the process of understanding the concepts and mechanisms underlying those tasks (Harden 1996). It is an example of experiential learning (Kolb 1984). The student learns about the different facets related to the task, basic sciences, pathology, pharmacology, decision making, communication skills and ethics. The approach also has been described as ‘service-based learning’ (Grant and Marsden 1992). The same task can be presented at different phases of the curriculum and in different learning and practice environments, for example skill labs, hospitals and general clinics, and it can also be presented at different dimensions of complexity.

TkBL offers a practical approach to integration in the curriculum as students learn by building activities around a number of tasks. They seek to understand the concepts related to the task and at the same time develop skills and proficiency in doing the task. Learning outcomes are products of the contributions of the individual learner, the task and the context of the ‘situation’. Tasks occupy a central place in a three-way relationship between teachers, learners and learning outcomes. The tasks can represent the outcome competences of a programme. One example is the Dundee curriculum (Harden et al. 1997). Tasks can be integrated with different types of curricula, as described in the case from University of Sharjah, United Arab Emirates, where they combine PBL, TBL and TkBL. The following case study describes how TkBL is implemented in the pre-clerkship phase of an integrated PBL curriculum.

Case study 10.5 Teaching and learning basic medical sciences in the clinical environment using a task-based learning approach at the University of Sharjah, United Arab Emirates

Basic medical sciences constitute a major component of the pre-clerkship phase regardless of whether the curriculum is discipline-based or integrated. The pre-clerkship phase of medical education is characterised by most of the teaching taking place in classrooms – lectures, PBL tutorials and clinical skills labs using simulators and simulated patients. In many colleges, there are lab sessions related to disciplines, e.g. anatomy, physiology, biochemistry.

The College of Medicine, University of Sharjah, United Arab Emirates created a strong link with teaching hospitals, allowing students in the pre-clerkship phase of the integrated, PBL, organ system curriculum to work around tasks that demonstrate the clinical application of the basic medical sciences in action. They are related mainly to clinical investigation, monitoring and/or management of patients in the hospital. A number of tasks are identified in relation to each organ system, for example, in the cardiovascular system, electrocardiography, echocardiography, measuring central venous pressure, lipid profiles, cardiac enzymes; in the respiratory system, respiratory function tests, ventilatory support, blood gas analysis and chest physiotherapy; and in the gastrointestinal system, upper and lower endoscopy, microbiology of Helicobactor pylori, stool culture, rectal pressure studies and oesophageal manometry. The radiological anatomy of each system is taught in the radiology department, including conventional x-rays, computed tomography, magnetic resonance imaging and invasive radiology.

There is a list of objectives for each task that students work towards during a visit to the hospital. Clinical teachers receive training in how to explain the tests and relate them to underlying basic medical sciences. Each student reflects after each session about the experience framed by six questions:

1 What have I observed?

2 What did I do?

3 What did I learn?

4 What am I uncertain about?

5 What do I need to do to address the uncertainty, the gaps I see and understand?

6 How will I evaluate progress?

This programme is in its second year of implementation. Attention to the logistics of implementation in the hospital is crucial. Important issues to be considered to promote success include: limiting the number of students in each session (approximately ten); preparatory training for clinical teachers; and coordination and communication between the programme director and the clinicians.

CBL is characterised by small groups of learners working around a written problem using creative problem-solving strategies with some advance preparation. Students use previous experiences (cases) to suggest approaches to solving the problems and to help interpret findings in the new situation. CBL requires combining reasoning with learning. The tutor, who is a facilitator and subject matter expert, actively shares responsibility for reaching key learning points (Srinivasan et al. 2007). A ‘tutor guide’ provides questions and a flexible framework for discussion. Students prepare in advance and, in contrast to PBL, the objectives of the problem are declared at the end of the session and feedback from the tutor is given to the students. Of particular interest in this method is when and how the tutor sees, understands and acts to influence learning in the role of a facilitator, and when and how she or he and the group choose the tutor’s role as one of sharing expertise in various forms, commonly as a lecture. The relationship between these roles is dynamic and depends on what is happening in the group at the time. Learning to see, understand and influence learning in this approach requires sensitivity to oneself, the group, to individuals, to the goals of the case, and sometimes all of these together.

Learning strategies such as CBL can be implemented in different formats and contexts:

• descriptive, narrative cases, parts of which may be given successively (progressive disclosure);

• mini-cases;

• directed case study – discussion of cases that may be long or short and are followed immediately with highly directed questions;

• ‘bullet cases’ – two or three sentences with a single teaching point, akin to examination questions.

CBL can approximate PBL and it can become like a lecture (Dufuis and Persky 2008) depending on conditions including class size, teachers’ training, capability and experience, students’ preparation, and the form and structure of the assessment system. It can be used with other learning strategies in a subject-based, coordinated or integrated curriculum.

It has been proposed that CBL may be better used to prepare younger learners in becoming better self-learners (Dufuis and Persky 2008). Learners using CBL are active and focused on application and problem solving. The following case from Sweden describes how CBL was introduced in the clerkship phase of a discipline-based curriculum.

Case study 10.6 Improving students’ decision-making skills on the surgical rotation

Karolinska Institute is a bio-medical university located in Stockholm, Sweden. Its medical programme is 5.5 years with an undergraduate intake of 250 students.

The curriculum has an integrated character divided into seven thematic areas. Students are exposed to patient contact during the first semester through primary care centres. Clinical rotations starts in the third year and are conducted at four different hospitals in Stockholm. The rotation in surgery is placed in the fifth year and consists of 16 weeks, including general surgery, anaesthesia, orthopaedic surgery and radiology.

The programme management of the surgical rotation at the Karolinska University Hospital Solna introduced CBL in 2008 with the intention of further activating students during their learning process and fostering integration of different medical subspecialties. CBL is a well-documented educational method originating from the Harvard Business School (Barnes et al. 1987). It fosters effective learning in groups (Thistlethwaite et al. 2012) and has the advantage that it can accommodate large groups with one facilitator. The method focuses particularly on analytical and decision-making skills. CBL has been adapted for medical students and was chosen by the University Hospital because of its potential to bridge the gap between traditional theoretical teaching and clinical experience (Barnes et al. 1987; Nordquist et al. 2012).

Fifteen cases were developed during 2009. Faculty development in facilitating case seminars took place during two semesters, with teachers being observed and receiving feedback from an educational consultant. Students were introduced to the new method during the introduction to the semester.

It was a challenge to produce 15 new cases in a rather short period of time. Medical doctors are not used to writing authentic cases in a narrative open-ended format from the perspective of one protagonist. Also, many faculty members were new to facilitating learning in a group of approximately 40 students, rather than giving a lecture. In addition, most students had never actively participated in case-based seminars during which they had to make their voice heard and to defend their decisions and positions publicly in a group of peers. Most importantly, students were not used to reasoning about possible solutions to a case.

Formative assessment focused on the level of implementation after two semesters. The managers of the programme were content with the assessment results and improvement of reflective skills among the students and how challenges were addressed (Nordquist et al. 2012).

It is crucial to dedicate adequate time for developing cases and for faculty development in facilitating skills. It is also very important to prepare students and to help them be aware of the programme expectations and what students should expect from the new teaching/learning method. It is clear that both faculty and students hold different expectations about CBL compared to the managers and educationalists planning the course. CBL works in harmony with other educational methods like subject-based learning and one does not need to change an entire curriculum as a result of its introduction.

In education a ‘one size fits all’ approach cannot be applied. Although a learning strategy of PBL, TBL, TkBL and/or CBL could be employed as the main learning method, in reality different methods are combined depending on the context, learning environment and the outcomes of learning.

Take-home messages

• Social constructivism is a common theoretical perspective of authentic learning strategies.

• Successful translation of an authentic learning method from a ‘curriculum on paper’ to actions ensures that student learning is the main challenge.

• Proper implementation of authentic learning needs knowledgeable and experienced leadership in medical education, faculty development, sensitivity to the context and institutional culture.

• The cost of introducing an authentic instructional method is an important element to be considered to ensure its sustainability.

• Monitoring what is happening and taking corrective actions needs to be built into all approaches. It is easy to keep the label of PBL or TBL while what is happening is a distorted version of one or the other.

• Assessment of students is a key part of success that must be in alignment with the strategies for learning, assessing both process and content.

• Authentic learning methods for health professionals will continue to evolve based on personal and contextual experiences. The current trend is to use a blend of learning methods guided by experience and general programme outcomes.

• All educational work requires continuous attention and multiple small adjustments on a regular basis. Failing to do this leads to much more difficult and expensive problems which are avoidable.

Bibliography

Abdelkhalek, N., Hussein, A. and Hamdy, H. (2010) ‘Using team based learning to prepare medical students for future problem-based learning’, Medical Teacher, 32(2): 123–9.

Anwar, K., Shaikh, A.A., Dash, N.R. and Khurshid, S. (2012) ‘Comparing the efficacy of team based learning strategies in a problem based learning curriculum’, ACTA Pathologica, Microbiologia et Immunologica Scandinavica, 120(9): 718–23.

Bandura, A. (1977) Social learning theory, New York: General Learning Press.

Barnes, L., Christensen, C. and Hansen, A. (1987) Teaching and the case method, Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Barrows, H.S. (1986) ‘A taxonomy of problem-based learning methods’, Medical Education, 20(6): 481–6.

Barrows, H.S. (1996) What your tutor may never tell you: A medical student’s guide to problem-based learning (PBL), Springfield, IL: Southern Illinois University School of Medicine.

Dede, C., Korte S., Neson, R., Valdez, G. and Ward, D.J (2005) Transforming learning for the 21st century: An economic imperative. Naperville, IL: Learning Point Associates. Online. Available HTTP: http://net.educause.edu/section_params/conf/eliws061/Dede_Additional_Resource.pdf 9 (accessed 24 April 2007).

Dolmans, D.H., Gijselaers, W.H., Moust, J.H., De Grave, W.S., Wolfhagen, J.H. and Van der Vleuten, C.P. (2002) ‘Trends in research on the tutor in problem-based learning: Conclusions and implications for educational practice and research’, Medical Teacher, 24(2): 173–80.

Dolmans, D.H.J.M., De Grave, W., Wolfhagen, I.H.A.P. and Van der Vleuten, C.P.M. (2005) ‘Problem-based learning: Future challenges for educational practice and research’, Medical Education, 39(7): 732–41.

Dufuis, R.E. and Persky, A.M. (2008) ‘Initial experience in using case-based learning in a clinical pharmacokinetics course’, American Journal of Pharmaceutical Education, 72(2): 29.

Grant, J. and Marsden, P. (1992) Training senior house officers by service-based learning, London: Joint Centre for Education in Medicine.

Hamdy, H. (2008) ‘The fuzzy world of problem based learning’, Medical Teacher, 30(8): 739–41.

Hamdy, H. and Agamy, E. (2011) ‘Is running a problem-based learning curriculum more expensive than a traditional subject-based curriculum?’, Medical Teacher, 33(9): e509–14.

Harden, R.M. (1996) ‘Task based learning: An educational strategy for undergraduate, postgraduate and continuing medical education, Part 1 (1996) AMEE medical education guide no. 7’, Medical Teacher, 18(1): 7–13.

Harden, R.M., Davis, M.H. and Crosby, J.R. (1997) ‘The new Dundee medical curriculum: A whole that is greater than the sum of the parts’, Medical Education, 31(4): 264–71.

Harden, R.M., Crosby, J.R. and Davis, M.H. (1999) ‘AMEE guide no. 14: Outcome-based education: Part 1 – an introduction to outcome-based education’, Medical Teacher, 21(1): 7–14.

Harden, R.M., Davis, M.H. and Crosby, J.R. (2000) ‘Task based learning: The answer to integration and problem based learning in the clinical years’, Medical Education, 34(5): 391–7.

Herrington, J., Oliver, R. and Reeves, T.C. (2003) ‘Patterns of engagement in authentic online learning environments’, Australian Journal of Education Technology, 19(1): 9–71. Online. Available HTTP: http://www.ascilite.org.au/ajet/ajet19/herrington.html (accessed 20 June 2014).

Hunt, D.P., Haidet, P., Coverdale, J.H. and Richards, B.F. (2003) ‘The effect of using team learning in an evidence-based medicine course for medical students’, Teaching and Learning in Medicine, 15(2): 131–9.

Kassab, S. and Hussain, S. (2010) ‘Concept mapping assessment in a problem-based medical curriculum’, Medical Teacher, 32(11): 926–31.

Knowles, M.S. (1980) The modern practice of adult education: From pedagogy to andragogy (2nd edn). New York, NY: The Adult Education Company.

Kolb, D.A. (1984) Experiential learning: Experience as the source of learning and development, Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Lave, J. and Wenger, E. (1991) Situated learning: Legitimate peripheral participation, Cambridge, MA: Cambridge University Press.

Lombardi, M. and Oblinger, D. (2007) ‘Authentic learning for the 21st century: An overview’, EDUCAUSE. Online. Available HTTP: http://net.educause.edu/ir/library/pdf/eli3009.pdf (accessed 20 June 2014).

Malik, A.S. and Malik, R.H. (2002a) ’The undergraduate curriculum of Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences, Universiti Malaysia Sarawak in terms of Harden’s 10 questions’, Medical Teacher, 24(6): 616–21.

Malik, A.S. and Malik, R.H. (2002b) ‘Implementation of problem-based learning curriculum in the Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences, Universiti Malaysia Sarawak’, Journal of Medical Education, 6(1): 79–86.

Margetson, D. (1997) ‘Why is problem-based learning a challenge?’ In D. Boud and G.E. Feletti (eds) The challenge of problem-based learning, London: Kogan Page.

Maudsley, G. (1999) ‘Do we all mean the same thing by problem based learning? A review of the concepts and formulation of the ground rules’, Academic Medicine, 74(2): 178–85.

McLaughlin, J.E., Roth, M.T., Glatt, D.M., Gharkholonarehe, N., Davidson, C.A., Griffin, L.M., Esserman, D.A. and Mumper, R.J. (2014) ‘The flipped classroom: A course redesign to foster learning and engagement in a health professions school’, Academic Medicine, 89(2): 236–43.

Mennin, S.P. and Martinez-Burrola, N. (1986) ‘The cost of problem-based vs traditional medical education’, Medical Education, 20(3): 187–94.

Michaelsen, L.K., Kinght, A.B. and Fink, L.D. (2002) Team based learning: A transformative use of small groups in college teaching, Sterling, VI: Stylus Publishing.

Murphy, J. (2003) ‘Task-based learning: The interaction between tasks and learners’, English Language Teaching Journal, 57(4): 353–60.

Nordquist, J., Sundberg, K., Johansson, L., Sandelin, K. and Nordenstrom, J. (2012) ‘Case-based learning in surgery: Lessons learned’, World Journal of Surgery, 36(5): 945–55.

Parmelee, D. and Hudes, P. (2012) ‘Team-based learning: A relevant strategy in health professionals’ education’, Medical Teacher, 34(5): 411–13.

Roberts, C., Lawson, M., Newble, D., Self, A. and Chan, P. (2005) ‘The introduction of large class problem-based learning into an undergraduate medical curriculum: An evaluation’, Medical Teacher, 27(6): 527–33.

Rorty, R. (1991) Objectivity, relativism and truth, Cambridge, MA: Cambridge University Press.

Savery, J.R. and Duffy, T.M. (1995) ‘Problem based learning: An instructional model and its constructivist framework’, Educational Technology, 35: 31–8.

Schmidt, H.G. (1993) ‘Foundations of problem-based learning: Some explanatory notes’, Medical Education, 27(5): 422–32.

Schon, D.A. (1983) Educating the reflective practitioner, San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Seidel, C.L. and Richards, B.F. (2001) ‘Application of team learning in a medical physiology course’, Academic Medicine, 76(5): 533–4.

Srinivasan, M., Wilkes, M., Stevenson, F., Nguyen,T. and Slavin, S. (2007) ‘Comparing problem-based learning with case-based learning: Effects of a major curriculum shift at two institutions’, Academic Medicine, 82(1): 74–82.

Taylor, D. and Hamdy, H. (2013) ‘Adult learning theories: Implications for learning and teaching in medical education: AMEE guide no. 83’, Medical Teacher, 35(11): e1561–72.

Thistlethwaite, J., Davies, D., Ekeocha, S., Kidd, J., MacDougall, C., Matthews, P., Purkis, J. and Clay, D. (2012) ‘The effectiveness of case-based learning in health professional education: A BEME systematic review: BEME guide no. 23’, Medical Teacher, 34(6): e421–44.

Von Glasersfeld, E. (1989) ‘Cognition, construction of knowledge and teaching’, Synthese, 80(1): 121–40.

Vygotsky, L.S. (1978) Mind in society. The development of higher psychological processes, Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.