14

IMPLEMENTING INTERPROFESSIONAL EDUCATION

What have we learned from experience?

Dawn Forman and Betsy VanLeit

There are significant advantages and lessons to be learned from sharing educational experiences between the different healthcare professions.

The changing demographics of healthcare demand a significant reassessment of the ways in which healthcare is delivered (Crisp 2010). Interprofessional education (IPE) is an important strategy to address these issues (McPherson et al. 2001; Thompson and Tilden 2009; World Health Organization (WHO) 2010). The WHO (2010) Framework for Action on Interprofessional Education and Collaborative Practice mandated all higher-education institutions to embed IPE in their curricula. Actions proposed to achieve this included:

• agreement on a common vision and purpose for IPE;

• development of interprofessional curricula according to principles of ‘good’ educational practice;

• creation of frameworks for clear interprofessional outcomes.

A number of definitions of IPE and practice are in use. This chapter incorporates the WHO (2010) definitions.

• IPE occurs when two or more professions learn about, from and with each other to enable effective collaboration and improve health outcomes.

• Professional is an all-encompassing term that includes individuals with the knowledge and/or skills to contribute to the physical, mental and social well-being of a community.

• Collaborative practice in healthcare occurs when multiple health workers from different professional backgrounds provide comprehensive services by working with patients, their families, carers and communities to deliver the highest quality of care across settings.

• Practice includes both clinical and non-clinical health-related work, such as diagnosis, treatment, surveillance, health communications, management and sanitation engineering.

Barr (2005) provides an overview of the development of IPE, and more recently Forman et al. (2014) provide a review of how international interprofessional developments have been led.

The present chapter provides case studies from around the world to exemplify how IPE and practice are being taken forward internationally and examines selected interprofessional developments in a wide range of socio-economic and political conditions. The chapter concludes by stating where advice can be gained for anyone introducing IPE and collaborative practice in their own environment.

Where did interprofessional education begin?

There is much debate about where IPE first began and, indeed, even more debate in the early years of IPE development about whether the best place to start IPE is at undergraduate or postgraduate level. Tope (1996) provides examples of innovative health professional education with aspects of shared learning or IPE from across Europe, Cameroon, Sudan, Mexico, Africa, Canada and the USA.

Linkoping University in Sweden is, however, widely acknowledged as an institution which, having initiated an undergraduate interprofessional, problem-based programme for healthcare professions in 1996, has the longest and most sustained history in this field. Their programme has been continuously evaluated and refined over the years; and recently, to ensure that changes in health and social care nationally and internationally as well as changes in politics, emerging technologies, demographics and health indices, have been taken into account, a renewed framework has been designed. This new curriculum incorporates four domains of interprofessional collaborative practice competencies:

1 values/ethics for interprofessional practice;

2 roles/responsibilities;

3 interprofessional communication;

4 teams and teamwork.

Linkoping seeks to develop leaders of change, and to ensure students strive for quality improvement and have strong ethical values (Abrandt Dahlgren et al. 2012). A problem-based, interprofessional learning methodology has been maintained, ensuring the students work together to resolve an issue, thereby learning with, from and about each other but also knowing more about each other’s role, and when and how to hand on to another professional. The overall aim is to ensure that at graduation students have the skills and competencies they will require in their future professional roles with a focus on the patient or client in all aspects.

Many institutions have chosen to provide a medical curriculum in which problem-based learning (PBL) is key. On the other side of the world, Notre Dame University in Australia utilises PBL as a means to incorporate interprofessional activities.

The review of interprofessional education in Australia

Recent reviews of healthcare in Australia identified the need for a new model of service delivery. It is clear that an integrated and interprofessional health service is required to meet the challenges of the future (Garling 2008; Commonwealth of Australia 2009, 2011; Government of Western Australia 2009; Health Workforce Australia 2011). The ability to practise collaboratively is necessary to deliver safe and appropriate client-centred care, effectively and efficiently (Meads et al. 2009).

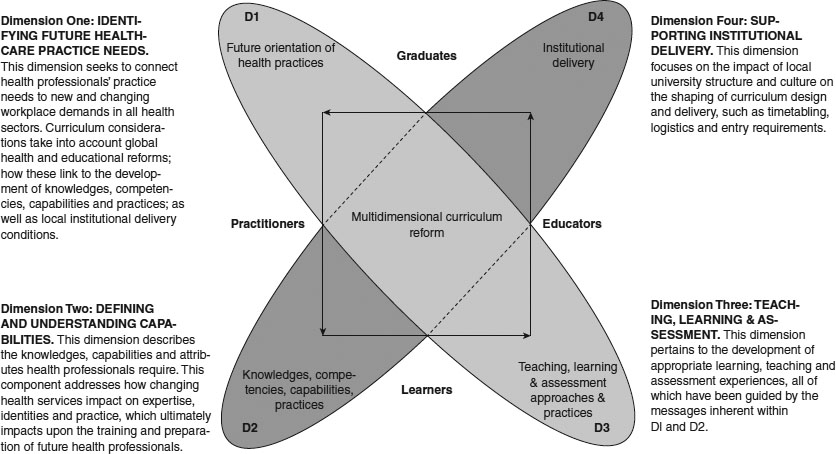

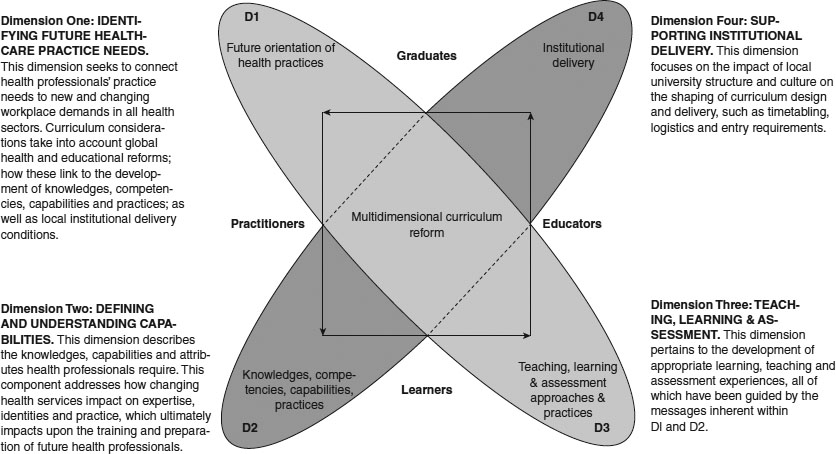

Figure 14.1 The four-dimensional interprofessional framework of Lee et al. (2013). Australian and New Zealand Association for Health Professional Educators (ANZAHPE) has freely granted permission to use the image, originally published in Focus on Health Professional Education, 14(3):70–83.

Australia has recently undertaken a national review of IPE efforts and is in the process of developing a national curriculum framework to guide the implementation of the approach by educational institutions. The framework will utilise a four-dimensional model for health professional curriculum development, expounded by Lee et al. (2013) (Figure 14.1). The methodology recognises the real potential for organisational and logistical barriers to impede the implementation of IPE (Dimension Four) and provides the impetus for overcoming these problems by reconnection with the high-level societal purpose for change (Dimension One). Teaching, learning and assessment are viewed as key in ensuring appropriate learning takes place (Dimension Three). But perhaps the most interesting aspects, as we look at the difference that IPE and collaborative practice makes to the client, are the capabilities that we develop in our students and practitioners (Dimension Two). Key to the development of these capabilities is the collaboration or partnership arrangements that are developed between the higher-education institution and the service or community in which the students and practitioners are working.

Case study 14.1 Weaving interprofessional education into the medical curriculum at the University of Notre Dame, in Western Australia

Carole Steketee and Donna B. Mak

Traditional medical courses have a discipline-based curriculum in which content is presented and learned in relative isolation (e.g. pharmacology, immunology, anatomy). However, patients, as human beings, function as an integrated whole; the University of Notre Dame’s medical curriculum recognises this and simultaneously provides students with learning experiences that enable them to encounter knowledge and skills from a wide range of disciplines in the context of authentic patient cases. Cases are delivered via a PBL programme in the first 2 years of the course and via contact with genuine patients in a variety of clinical settings in the final 2 years.

IPE therefore is not teased out and delivered as a discrete subject. Instead, it is co-embedded with the curriculum and integrated within the fabric of patient cases. Nevertheless, at the broad learning outcome level (each unit is 1 year in length), there is a distinct focus on interprofessional healthcare practice. For example, in the first year of the course students will demonstrate an understanding of the importance of interprofessional healthcare of patients. In the second year, students will participate in opportunities of interprofessional learning and healthcare. In the third year, students will work effectively within an interprofessional healthcare team and in the final year, students will work collaboratively as integral members of an interprofessional healthcare team to provide high-quality patient-centred care.

Some examples of activities and learning experiences that enable students to address these learning outcomes are multidisciplinary panel discussions based on hypothetical cases, e.g. a 15-year-old girl seeking contraception from the school nurse; and a married, middle-aged man who feels sexual attraction to a work colleague of the same sex. These panels usually comprise a patient or health consumer representative with first-hand experience of the condition being discussed and a variety of relevant health professionals, each contributing to the discussion on an equal footing.

During clinical rotations in the final 2 years of the course, students attend team meetings and observe the functioning of a multidisciplinary team. In the final year, students are expected to present at these meetings. Lectures are provided by a range of healthcare professionals in relation to the patient-based problem of the week (e.g. lecture by a dietician with regard to changes in nutritional requirements throughout the life cycle, particularly as it pertains to the elderly and groups with neurological conditions such as Parkinson’s disease). Rural and remote community placements take place, where students learn with, and from, local residents in non-clinical settings about health and other issues they face in the bush. In these encounters, the local resident is an equal in the team and directs student learning around issues of importance.

The UK Centre for the Advancement of Interprofessional Education (CAIPE) defines IPE as occurring when ‘two or more professions learn with, from and about each other to improve collaboration and the quality of care’ (CAIPE 2002). In light of this definition, many of the activities above are not ‘pure’ IPE. While students learn about and from other health professionals, they do not collaborate with other health professional students to do so. The logistics of coordinating multiple complex timetables has been expressed as the primary reason why this has not occurred to date.

Freeth et al. (2005: 8) suggest that IPE is:

The activities delivered in the School of Medicine at Notre Dame are more aligned to this definition of IPE in that their focus is on helping students understand the role of the patient in their care, particularly in the light of increasing chronic disease and an ageing population. For example, students on placement in the Kimberley (a remote region in Western Australia) are immersed in the community and learn primarily from the locals about the health and societal issues they face. In this context, students learn from Aboriginal language interpreters and are exposed to the role of the Aboriginal health workers and environmental health workers. They examine the functions and dynamics of multidisciplinary teams and other health professionals, and their contributions to health and disease prevention/management in this setting.

An integrated curriculum in medical education has the advantage of providing students with rich, purposeful and contextualised learning opportunities. However, it is not without its challenges. This is evident in the case of IPE, where it would be much easier (and a lot less expensive) to provide students with a discrete unit on the topic. However, integration requires IPE (and other topics) to be woven together with patient problems in an authentic and purposeful way, and then to be resourced accordingly. The School of Medicine at the University of Notre Dame, Australia, does this by way of patient-centred problems. The outcome of this approach could be described as interdisciplinary learning rather than IPE. The curriculum developers will continue to address this issue during review cycles. Participation in a national project on curriculum review in IPE has been instrumental in informing this endeavour.

Two case studies, one from the Philippines and one from Kenya, provide examples of how the partnership between the higher-education institution and the community environment where the students and practitioners are working has enabled interprofessional collaboration (IPC) to be developed to the benefit of the community.

Case study 14.2 Developing community-engaged interprofessional education in the Philippines

Reproduced from Leadership Development for Interprofessional Education and Collaborative Practice, edited by Dawn Forman, Marion Jones and Jill Thistlethwaite, published 2014 by Palgrave Macmillan, reproduced with permission of Palgrave Macmillan.

Elizabeth R. Paterno, Louricha A. Opina-Tan and Dawn Forman

In 2007, the Community Health and Development Program (CHDP) was inaugurated as a unit of the University of the Philippines (UP) Manila. It was mandated to forge partnerships with rural municipalities, to set up and maintain community-based health programmes that would benefit both the municipality and the university, and to provide the site for student immersion programmes of all UP Manila academic units, namely the Colleges of Medicine, Nursing, Public Health, Dentistry, Pharmacy, Allied Medical Professions (occupational therapy, physical therapy and speech therapy) and the Arts and Sciences. Two colleges of UP Diliman (another UP campus in Quezon City), the College of Social Work and Community Development and the College of Home Economics, specifically the Department of Nutrition, also joined the programme.

The two objectives of the CHDP agreed upon by all participating units were to provide learning opportunities for the faculty and students of UP Manila in the principles and practice of community healthcare; and to assist communities to attain increasing capacities in their own healthcare and development through the primary healthcare approach.

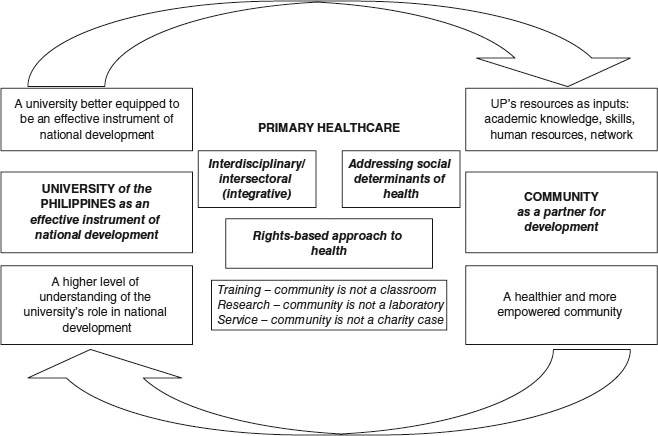

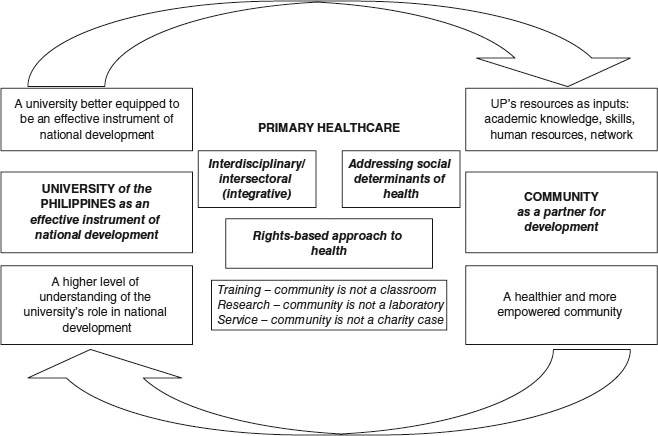

All the participating colleges agreed upon a common conceptual framework, that genuine improvement in community health and development should be one of the most important outcomes of the partnership. Figure 14.2 graphically explains this conceptual framework.

Development of collaborative patient care and interprofessional education

Prior to 2007, each UP Manila college had its own community immersion site and therefore the colleges had developed their own protocols on community health work. Though the interdisciplinary approach had been articulated as one of the principles that would guide the work in the common community, in practice there were no guidelines on how this would actually be done. In the initial year of programme implementation at the common site, each discipline managed patients independently but referrals to other disciplines were done when deemed necessary according to the patient’s needs. As such, patients were often managed by different disciplines at the same time. However, there were no clear guidelines for coordination. Patient management was not streamlined, and was often repetitive. Patients and their families often became fatigued having to entertain different sets of students several times within a day or week, and it was not uncommon, after a few weeks of treatment, for patients to refuse to entertain students.

The evaluation

An evaluation of the programme was done at the end of the first year of implementation where the observations stated in the previous paragraph were documented. The assessment meeting was followed by a study of available literature from other countries where interdisciplinary learning had been taking place for some time. Important lessons gathered from the literature review and affirmed by our experiences included the following:

Figure 14.2 Conceptual framework of the Community Health and Development Program, University of the Philippines (UP). (Reproduced from Leadership Development for Interprofessional Education and Collaborative Practice, edited by Dawn Forman, Marion Jones and Jill Thistlethwaite, published 2014 by Palgrave Macmillan, with permission of Palgrave Macmillan.)

• Equality and collegiality among the different disciplines are necessary characteristics of a successful collaborative practice. The existing hierarchical relations among the disciplines in the university hospital setting therefore had to be overcome.

• Professionals working together should share common goals, objectives and activities relevant to their practice.

• Understanding and valuing the roles played by other professionals facilitate the development of IPC.

• Having time to interact as well as sharing common working space reduce professional territoriality.

• Good communication among the different disciplines should be an active work, and the value of group discussions among students of different disciplines should be emphasised. Having common documents facilitates communication.

With members of faculty staff working with community representatives, guidelines were developed, agreed upon and implemented. This led to the university being able to implement its framework and improve interprofessional collaborative community practice.

Case study 14.3 COBES at Moi University, Faculty of Health Sciences, Eldoret, Kenya

Reproduced from Leadership Development for Interprofessional Education and Collaborative Practice, edited by Dawn Forman, Marion Jones and Jill Thistlethwaite, published 2014 by Palgrave Macmillan, reproduced with permission of Palgrave Macmillan.

Simeon Mining and Dawn Forman

IPE at the College of Health Sciences began in 1996 when the first class of environmental health students joined the medical students for community-based education and services (COBES). This first class was developed following discussions which had taken place through the partnership with Linkoping University, beginning in 1989. This partnership was the initiative of the Ministry of Health in Kenya and a formal agreement was signed in 1990. The partnership is still continuing and evolving, and offers opportunities for both staff and student exchange. The initial joining of environmental health and medical students was quickly followed by the addition of nursing students, and now dentistry, physical therapy and medical psychology are also included.

(Godfrey et al. 2000)

This quote provides a good illustration of the advantages of the community-based training programmes at Moi University in Eldoret, Kenya. Students from these programmes cooperate on site in the COBES programme and thus practise community-based, multiprofessional education.

The COBES programme is divided into five phases:

1 introduction to the community;

2 community diagnosis;

3 writing a research proposal;

4 investigation – executing the research plan;

5 district health service attachment.

The research projects designed and implemented in Phases 3 and 4 have resulted in the most fascinating reports. The projects in Phase 3 are designed on the faculty’s premises, with students then going out into the community again to collect data during Phase 4. The research topics addressed are diverse, ranging from Women’s self-help groups as change agents in alleviating malnutrition among under-fives, to Knowledge, attitude and practice of hygienic food handling among kiosk food vendors in Eldoret.

Attaining the skills required as a healthcare professional

In each of the case studies it is clear that the universities recognise the need to ensure that graduates entering the profession apply and practise knowledge and skills beyond the theoretical knowledge learned at university, and implement newly acquired competencies (Higgs et al. 2004). As this learning is context-based in the community of practice (Dahlgren et al. 2004), peers, role models, mentors and supervisors can significantly influence the quality of learning (Goldenberg and Iwasiw 1993; Ajjawi and Higgs 2008; Johnsson and Hager 2008). Successful adaptation relies on social learning and active participation in reflection, and feedback from reliable others to judge actions and decisions (Regehr and Eva 2007). Self-directed learning, critical thinking, reflective practice, adaptability and flexibility are highlighted as skills for lifelong learning (Barr 2002; Smith and Pilling 2007); development of these skills in the practice environment during this critical transition time facilitates graduates’ successful transition to the workforce (Smith and Pilling 2007; Johnsson and Hager 2008).

Assessing collaborative practice

A recently published systematic review identified an inventory of 128 quantitative tools relevant to IPE or collaborative practice (Canadian Interprofessional Health Collaborative (CIHC) 2012). The inventory was designed to assist in making the challenging decision about which tool to use for various contexts, as each tool has different strengths. IPE is difficult to deliver in the clinical setting and there are limitations in the way it is evaluated (Barr et al. 2000; Hammick et al. 2007; Gillan et al. 2011). Quantitative data collected frequently evaluate learners’ responses to the programme on the basis of self-assessment of changes in skills. Qualitative data are predominantly students’ satisfaction with the experience. This reliance on self-reported data is a weakness of many studies (Hammick et al. 2007). There is a need to include qualitative methods to provide insight about collaboration and how this contributes to changes in outcomes (Reeves et al. 2009).

It is much more difficult to measure changes in behaviour, impact on the community and benefits to the client resulting from the IPE experience, and it is done much less often (Barr et al. 2000). There is no single tool that has been adopted as the ‘gold standard’ (Gillan et al. 2011). Gillan and colleagues concluded it is not feasible for one comprehensive tool to cover all IPE outcomes, and a toolkit is needed rather than a single instrument.

Tailoring your interprofessional programme to your environment

The context and circumstances in which IPE and collaborative practice take place vary, and lead to the need for different types of leadership, development and sustainability.

The following case studies from New Zealand, Egypt and the USA provide examples of three different international interprofessional environments.

Case study 14.4 Interprofessional education in a rural clinical setting – a quick-start innovation for final-year health professional students, University of Otago, New Zealand

Sue Pullon, Eileen McKinlay, Peter Gallagher, Lesley Gray, Margot Skinner, and Patrick McHugh (with acknowledgements also to Rachael Vernon, Ruth Crawford, Jennifer Roberts, James Windle, Lyndie Foster Page, John Broughton, Bridget Robson, Louise Beckingsale, Rose Parsons, Maaka Tibble, Hiki Pihema, Anne Pearce, Natasha Ashworth, Marty Kennedy, David Edgar and Christine Wilson)

New Zealand (NZ) is a small country with increasing cultural and ethnic diversity. Maˉori (indigenous peoples) make up 16 per cent of the population. The University of Otago offers health professional degrees in dentistry, medicine, pharmacy, physiotherapy and dietetics. An IPE programme for final-year health professional students was called for by Health Workforce NZ to address educational objectives relating to interprofessional practice, hauora Maˉori (Maˉori health), rural health and chronic conditions management. The programme involves six health disciplines: those mentioned above plus nursing, in collaboration with the Eastern Institute of Technology (EIT).

The chosen programme site is an isolated, largely rural area. There are high levels of unemployment and socio-economic deprivation. Forty-nine per cent of the population is Maˉori, who are young with low age of first birth (Dew and Matheson 2008; Statistics NZ 2010). Health need in the region is high, with an undisputed requirement to increase the rural health workforce and to ensure that health professional work is collaborative and well coordinated.

The University of Otago programme was developed from an initial business case and implemented as one of two parallel rural sites – the other being run by the University of Auckland. Common learning outcomes were agreed across both sites; however, institutional and local variables required separate set-up and implementation strategies. An interdisciplinary group of senior academic teachers worked together to devise a 5-week rotational programme. The group reports to a multi-stakeholder governance group and developed relationships with a local Tairaˉwhiti steering committee, a local Maˉori advisory group and a local education provider. The programme has a local academic leader, a local administrator and a part-time clinical supervisor/teacher in each of the disciplines and in hauora Maˉori.

During the programme, groups of ten to 12 students from four to six disciplines at a time come to the region and live together in shared accommodation. The intended learning outcomes are met with a mix of ‘clinical home’ placements, interprofessional clinical placements and group activities, including a summatively assessed group community education project. The project topic is chosen by a local community or health provider involved in the development of a community resource and is an important reciprocal gesture. Clinical placements are most often in the community – e.g. general practices, community pharmacies, rural Maˉori health service providers – but some are at the local rural hospital, e.g. community physiotherapy clinic.

The short set-up time frame was challenging and improvements were needed in each successive block during Year One. There is no curricular or temporal alignment between each participating degree programme, thus making agreed dates, commonly agreed learning outcomes and assessment difficult to achieve. For most, this was the first opportunity for academic course leaders to participate in an interprofessional programme. Providing adequate resources and support for new, distant clinical teachers and clinical provider organisations has been an additional challenge, especially for those unfamiliar with e-learning environments.

The project is being independently evaluated over 3 years. First-year results indicate significant community commitment and very positive student feedback in relation to local hospitality, feeling part of the healthcare team, learning from students of other disciplines and much greater appreciation of the rural health environment. Students report greatly increased confidence in working with Maˉori, and enjoy producing their community projects. Some students were concerned that they were missing out on their discipline-specific clinical experience, and changes were needed to ensure continuity in a ‘clinical home’. Capacity to take students on clinical placements is limited in areas with small populations. Providers and staff need continued support and ‘rest periods’ for sustainability.

The set-up of a new interprofessional programme is complex. From the outset, all disciplines need to be involved in governance, planning and curricular design to remain engaged and committed. Without this there is no commitment to student supply or ongoing staff support. Temporal course alignment is not possible when quick set-up is required. Adaptations are required from all disciplines. Clinical teachers need guidance to develop an ‘interprofessional identity’ to support students’ learning in new ways. Clinical capacity needs active management, and excellent administration and coordination. Roll-out to multiple sites needs interprofessional leadership, local flexibility, well-developed resources and skill acquisition for local clinicians in the use of IPE methods and e-learning tools.

Another example of interprofessional community education can be seen in Ismailia, Egypt, where the focus has been on developing the interprofessional programme with a focus on the needs of the community and working with the community to address this issue.

Case study 14.5 Applying interprofessional education in primary care facilities for fourth-year students at the Faculty of Medicine, Suez Canal University, Egypt

Somaya Hosny and Mohamed H. Shehata

Community-based education (CBE), with its focus on integrative learning, provides a very appropriate environment for introducing IPE activities. To improve students’ learning experiences, an integrated module on infection control was implemented in 2010–11 for the fourth-year medical students. Students were expected to develop their competencies in infection control, leadership, quality improvement and IPE/IPC.

Instead of receiving didactic lectures about the subject, students were assigned a group task to improve one area of performance related to infection control (for example, hand hygiene among providers of care). Students were trained to do the task in a systematic way using the Challenge Model (Galer and Vriesendorp 2001), to observe the current situation, analyse the root causes, identify the key obstacles and provide a solution. They used Ministry of Health infection control standards to observe the compliance of workers with hand-washing steps. They worked with multidisciplinary teams in the primary care facilities (nurses, physicians, dentists and manual workers) to analyse the reasons for the lack of compliance. This was followed by brainstorming sessions to suggest simple solutions to improve the compliance of the healthcare team. The experience of working with a multidisciplinary team to improve the compliance of the healthcare team with hand hygiene was highly valued by students and teachers (Hosny et al. 2013). Difficulties encountered included: the need to train all field tutors on this particular model of improvement, and involving other professions without the required background for the Challenge Model. In addition, the limited time for the task precluded students from going through the monitoring and evaluation of outcomes of their efforts.

In spite of these obstacles, the feedback was excellent from all parties:

• Healthcare providers appreciated this simple approach and valued the mutual learning experience with the students.

• Tutors thought that the best outcomes of this experience were motivating students to be future leaders, increased sense of responsibility among students about the quality of care provided and, more importantly, being able to work with multidisciplinary teams.

• Most of the students enjoyed working in this practising environment where they could express their thoughts and apply their ideas for improvement.

• What students valued most was working with their peers in a real professional context on real-life problems. They said this experience would definitely help them overcome obstacles in the future.

CBE is an effective medium for integrated learning and application of IPE. Tutor training is crucial for successful implementation of such models. A more elaborate programme evaluation would be beneficial. Medical schools should allow more time for such activities and design specific IPE modules.

In New Mexico, USA, the context of working with a rural community and addressing their needs has also played an important part in the design of the interprofessional programme.

Case study 14.6 Interprofessional education to prepare health professionals for rural practice in underserved New Mexico communities, USA

Betsy VanLeit

New Mexico is a vast, rural state with significant inequities in access to healthcare. Most of the counties in the state are underserved, lacking health professionals or accessible systems of care. This is particularly problematic in regions of the state that have large Hispanic and American Indian populations. In this context, the University of New Mexico Health Sciences Center (UNMHSC) has a vision of working with community partners in order to help New Mexico make great strides in health and health equity. The mission of the UNMHSC is to provide an opportunity for all New Mexicans to obtain an excellent education in the health sciences, and to advance health sciences in the most important areas of human health with a focus on the priority health needs of regional communities.

The UNMHSC has spearheaded many initiatives over the past few decades to build a strong healthy workforce that is committed to serving communities throughout the state. This case study describes one of those initiatives, called the Rural Health Interdisciplinary Program (RHIP), created and sustained for many years with federal training grant dollars. The intent was to provide health professions with training that prepared students for teamwork and introduced them to rural practice in a manner that was attractive and compelling. The RHIP operated from 1991 until 2008. Unfortunately, we were not able to keep the programme going without additional resources. RHIP was time-intensive for the academic instructors, and without salary support the academic instructors were unable to maintain their involvement. In addition, the loss of financial support for rural coordinators, student housing and travel made it impossible to maintain the rural component of the programme. Repeated attempts to obtain institutional support and/or support from the state legislature were unsuccessful and RHIP closed its doors in 2008.

The RHIP initially involved the academic instructors and ten students from the fields of medicine, nursing, pharmacy and physiotherapy. The programme, at its peak, annually involved over 100 students from 12 health-related disciplines – dental hygiene, public health, medical laboratory sciences, medicine, nursing, occupational therapy, pharmacy, physical therapy, physician assistant, respiratory therapy, social work and speech language pathology.

There were two major phases to the RHIP each year. In January, students and faculty were divided into interprofessional teams that spent several months together on campus engaged in interprofessional weekly PBL sessions. Teams typically consisted of eight to 12 students, and one or two academic instructors, and most groups had representation from four to six professions. Teams were assigned according to the community where they would complete clinical rotations later in the year.

The first PBL case was developed and facilitated by academic instructors. After that, students took the lead in developing and facilitating PBL cases, with academic instructors playing more of a supportive role. The PBL scenarios were designed to require interprofessional teamwork to evaluate and address complex health issues. The cases highlighted the multidimensional nature of community-based healthcare problems, including cultural, ethical, regional, financial and legal issues. The cases reflected a wide variety of conditions commonly seen in rural New Mexico, and they dealt with the full continuum of care (acute care, rehabilitation, chronic management, prevention and health promotion).

During the months of June and July, student teams completed the off-campus component of RHIP in selected rural communities. Teams lived rurally while completing clinical training that was specific to their own profession. Our original goal was to offer students opportunities to do clinical training in teams; however, this rarely reflected the reality of practice. For example, a pharmacy student might train at the local pharmacy, while the medical student trained at a local clinic, and the nursing student and the occupational therapy student trained at the local hospital in different departments. Living and working in rural communities provided the students with experience and appreciation for rural health practice and the culture of the region. In addition, this gave rural communities an opportunity to recruit graduating students as healthcare providers. Student groups in the communities were also responsible for completing a small interprofessional health project identified by the community. An on-site rural coordinator helped the students to connect with community leaders and organisations and to facilitate student integration with community life. Faculty from UNMHSC drove to the communities on a weekly basis to participate with students during this phase.

The RHIP evaluation, completed annually, consistently found that participants increased their positive perceptions of working in rural and underserved communities, and increased their confidence and intent to engage in interprofessional practice. Many of the students commented that RHIP was the highlight of their educational experience and that they thought all students should participate. A longitudinal follow-up study indicated that 36 per cent of all participants chose to practise in rural communities, and 46 per cent practised with underserved populations after graduating. A qualitative study using extensive interviews and reflective logs highlighted the many ways that students came to appreciate the complexity of health and healthcare needs in rural and remote communities as a result of participating in RHIP.

Although the RHIP was highly valued by academic instructors, students and rural communities, it was expensive and logistically complex to administer. It required extensive academic instructor involvement during all phases of the programme, ongoing involvement on the part of community coordinators all around the state, a full-time administrator to oversee day-to-day operations and funding to support student housing and travel. This is why, when the federal funding disappeared, UNMHSC was unable to keep the RHIP operating as a coherent initiative. Currently, we offer some interprofessional PBL on campus, and new innovations include the use of team assessments of standardised patients. In addition, some students are still able to engage in interprofessional service learning in community settings, but it is more sporadic than it was in the past.

We have learned that key elements to assuring the ongoing success of this type of curricular innovation include:

• active support of the top leadership in the institution;

• buy-in from academic instructors and administrators in multiple professional programmes;

• coordinated schedules between multiple professional programmes;

• financial support that reflects the costs of travel, housing, academic instructors’ time and administrative support.

This chapter highlights how IPE and practice are now being seen as important internationally. It is only right that different countries, communities and organisations develop interprofessional activities in ways which are appropriate to their context. What is equally important, however, is that internationally we share experiences and learn with and from one another.

Useful websites for information for interprofessional education and collaborative practice

Take-home messages

• Interprofessional education and collaborative practice are now taking place internationally.

• There is literature now available on this topic and a number of websites can be consulted for further advice and information (see above).

• There is, however, still a lot of work needed in this area to ensure that interprofessional activities are evaluated.

• A greater evidence base is required to demonstrate the difference that IPC can make both to individuals and to their community.

Bibliography

Abrandt Dahlgren, M., Dahlgren, L.O. and Dahlberg, J. (2012) ‘Learning professional practice through education’. In P. Hager, A. Lee and A. Reich (eds) Practice, learning and change, New York, NY: Springer.

Abrandt Dahlgren, M. Richardson, B. and Sjostrom, B. (2004) ‘Professions as communities of practice’. In J. Higgs, B. Richardson and M. Dahlgren (eds) Developing practice knowledge for health professionals, Edinburgh: Butterworth Heinemann.

Ajjawi, R. and Higgs, J. (2008) ‘Learning to reason: a journey of professional socialisation’, Advances in Health Sciences Education: Theory and Practice, 13(2): 133–50.

Barr, H. (2002) Interprofessional education: Today, yesterday and tomorrow, London: LTSN Health Sciences and Practice.

Barr, H. (2005) Interprofessional education today, yesterday and tomorrow: A review (revised ed), London: Higher Education Academy: Health Sciences and Practice.

Barr, H., Freeth, D., Hammick, M., Koppel, I. and Reeves, S. (2000) Evaluating interprofessional education: A UK review for health and social care, London: British Educational Research Association and CAIPE.

Canadian Interprofessional Health Collaborative (2012) Inventory of quantitative tools to measure interprofessional education and collaborative practice, Vancouver: Canadian Interprofessional Health Collaborative.

Centre for the Advancement of Interprofessional Education (CAIPE) (2002) Interprofessional education – A definition, London: CAIPE.

Commonwealth of Australia (2009) A healthier future for all Australians: Interim report December 2008, Canberra: National Health and Hospitals Reform Commission.

Commonwealth of Australia (2011) National Health Reform Agreement: National partnership agreement on improving public hospital services, Canberra: Department of Health and Ageing.

Crisp, N. (2010) Turning the world upside down, Boca Raton, FL: RSM Press.

Dew, K. and Matheson, A. (2008) Understanding health inequalities in Aotearoa New Zealand, Dunedin: Otago University Press.

Forman, D., Jones, M. and Thistlethwaite, J. (eds) (2014) Leadership development for interprofessional education and collaborative practice, London: Palgrave Macmillan.

Freeth, D., Hammick, M., Reeves, S., Koppel, I. and Barr, H. (2005) Effective interprofessional education development, delivery and evaluation, Oxford: Blackwell Publishing.

Galer, J.B. and Vriesendorp, S. (2001) ‘Developing managers who lead. The manager (Boston)’, Management Science for Health, 10(3): 2.

Garling, P. (2008) Final report of the Special Commission of Inquiry: Acute care in NSW public hospitals, 2008 – Overview, Parramatta, New South Wales: Department of Police and Justice (NSW).

Gillan, C., Lovics, E., Halpern, E., Wiljer, D. and Harnett, N. (2011) ‘The evaluation of learner outcomes in interprofessional continuing education: A literature review and an analysis of survey instruments’, Medical Teacher, 33(9): e461–70.

Godfrey, R., Odero, W. and Ettyang, G. (2000) Handbook of community based education: Community Based Education and Services (COBES), Faculty of Health Sciences, Moi University, Eldoret, Kenya: Network Publications.

Goldenberg, D. and Iwasiw, C. (1993) ‘Professional socialisation of nursing students as an outcome of a senior clinical preceptorship experience’, Nurse Education Today, 13(1): 3–5.

Government of Western Australia (2009) WA health clinical services framework 2010–2020, Perth, Western Australia: Department of Health.

Hammick, M., Freeth, D., Koppel, I., Reeves, S. and Barr, H. (2007) ‘A best evidence systematic review of interprofessional education: BEME guide no. 9’, Medical Teacher, 29(8): 735–51.

Health Workforce Australia (HWA) (2011) National health workforce innovation and reform strategic framework for action 2011–2105. Online. Available HTTP: http://www.hwa.gov.au/sites/uploads/hwa-wir-strategic-framework-for-action-201110.pdf (accessed 15 July 2014).

Higgs, J., Andresen, L. and Fish, D. (2004) ‘Practice knowledge – Its nature, sources and contexts’, in J. Higgs, B. Richardson and M. Dahlgren (eds) Developing practice knowledge for health professionals, Edinburgh: Butterworth Heinemann.

Hosny, S., Hany Kamel, M., El-Wazir, Y. and Gilbert, J. (2013) ‘Integrating interprofessional education in community-based learning activities; case study’, Medical Teacher, 35 (Supp 1): S68–73.

Johnsson, M.C. and Hager, P. (2008) ‘Navigating the wilderness of becoming professional’, Journal of Workplace Learning, 20(7/8): 526–36.

Lee, A., Steketee, C., Rogers, G. and Moran, M. (2013) ‘Towards a theoretical framework for curriculum development in health professional education’, Focus on Health Professional Education, 14(3): 70–83.

McPherson, K., Hendrick, L. and Moss, F. (2001) ‘Working and learning together good-quality care depends on, but how can we achieve that?’, Quality in Health Care, 10 (Supp 2): 46–53.

Meads, G., Jones, I., Harrison, R., Forman, D. and Turner, W. (2009) ‘How to sustain interprofessional learning and practice: Messages for higher education and health and social care management’, Journal of Education and Work, 22(1): 67–79.

Reeves, S., Zwarenstein, M., Goldman, J.M., Barr, H., Freeth, D., Hammick, M. and Koppel, I. (2009) ‘Interprofessional education: Effects on professional practice and health care outcomes (review)’, Cochrane Database System Review(1): CD002213.

Regehr, G. and Eva, K.W. (2007) ‘Self-assessment, self-direction, and the self-regulating professional’, Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research, 449: 34–8.

Smith, R.A. and Pilling, S. (2007) ‘Allied health graduate program: Supporting the transition from student to professional in an interdisciplinary program’, Journal of Interprofessional Care, 21(3): 265–76.

Statistics NZ (2010) Demographic trends: 2010. Government Statistics NZ. Online. Available HTTP: http://www.stats.govt.nz/browse_for_stats/population/estimates_and_projections/demographic-trends-2010/chapter2.aspx (accessed 18 July 2014).

Thompson, S.A. and Tilden, V.P. (2009) ‘Embracing quality and safety education for the 21st century: Building interprofessional education’, Journal of Nursing Education, 48(12): 698–701.

Tope, R. (1996) Integrated interdisciplinary learning between the health and social care professions: A feasibility study, Aldershot: Avebury.

World Health Organization (2010) Framework for action on interprofessional education and collaborative practice, Geneva: World Health Organization.