22

RECOGNISING LEADERSHIP AND MANAGEMENT WITHIN THE MEDICAL SCHOOL

Khalid A. Bin Abdulrahman and Trevor Gibbs

Over the past two decades there have been significant changes in the organisational structure within medical schools around the globe.

Effective leadership and management are considered essential for the development and sustainability of an effective organisation (Long 2011). Today’s medical schools are complex, adaptive organisations (Glouberman and Zimmerman 2002) that are measured on their effectiveness at fulfilling multiple functions: creating world-class healthcare practitioners; employing and developing world-class faculty; demonstrating expertise in research, teaching and service; maintaining a national and international perspective; and having to succeed in creating a financially stable and increasingly unique and recognised institution.

A successful school fulfils its mission through leadership and management, together. Without leadership, medical schools fail to keep pace with changing circumstances, and fail to produce graduates with the capacity to provide high-standard healthcare for the 21st century (Boelen et al. 2013). Large amounts of money are spent developing world-class medical schools that aspire to produce world-class health practitioners. The responsibility for this is placed firmly in the hands of the leaders of the school, who through leadership seek to satisfy this aspiration. However, the path to success is not an easy one and the concept and development of leadership are fraught with difficult challenges. For too many years there has been a barrier between ‘the clinicians’ and the organisational leadership. A lack of leadership training, a disjointed career structure and a wide differential in financial remuneration created barriers for clinicians and academics seeking to become involved with, and to assume responsibility for, leadership within the institution. The emergence of health managers, particularly in the UK, Europe and the USA, has disincentivised clinicians from becoming managers (Hamilton et al. 2008), while some of the ‘blame catastrophes’ occurring in certain hospitals have driven clinicians away from taking leadership roles (Department of Health 2002). Given the symbiotic relationship between clinicians, health services and medical schools, it is inevitable that reluctance to take on a leadership role has also pervaded the medical school. For many, leadership still remains a rather nebulous and ill-structured concept, probably related, in part, to its variability in definition, its overlap with the concepts of leader and management, and its necessary dynamic quality, suggesting that leadership continuously needs to be adaptive to changing and variable circumstances. If medical schools are to move forward, this confused state around the subject of leadership and management needs clarification, while at the same time recognising that there are specific roles for those with responsibility to support this move. The emergence of ‘adaptive leadership’ addresses many of these concerns (Heifetz et al. 2009; Thygeson et al. 2010).

This first part of the present chapter will use three commonly heard statements to distinguish between the terms leadership, management and leaders, while the second half will use three cases drawn from specific medical schools to illustrate how the qualities of each can effectively promote conditions that can deliver a quality product.

The what and why of leadership

The following quotations, taken from years of experience in medical education, go some way to support the lack of clarity between the three terms.

• ‘I was appointed as a leader and therefore I already must have leadership skills.’

• ‘Leaders are born leaders and therefore leadership cannot be taught.’

• ‘I only manage programmes and therefore I do not need leadership skills.’

Leadership is frequently quoted as an essential skill required of anyone who takes responsibility for developing an educational institution, and in relation to this chapter, a medical school. However, it is difficult to argue against the similar presence of effective management and leaders in the development of that same institution. If we are to agree with Jonas and colleagues (2011) in their paper describing the importance of clinical leadership within the UK National Health Service (NHS), leadership is vital to the success of healthcare organisations, bringing quality, cost-effectiveness, change management and direction, and it is a quality that should pervade the whole organisation. They consider that these markers of effective leadership translate to all organisations that desire to succeed in a competitive world. Medical schools are employers and as such the effective management of their workforce is essential. We also attest to the importance of medical school leaders in their specific fields; indeed, most medical schools rely on specific specialty leaders to generate research income and to bring national and international status to the school.

Hence, it appears that we have three interchangeable terms, frequently used incorrectly due to a lack of clarity in their definitions and applications.

According to Kotter (1990), management is a relatively recent concept. He suggests that it has risen to prominence only within the last 100 years in response to the development of large complex organisations such as the railroad systems and the automotive industries. Management involves a series of processes, categorised into three groups: planning and budgeting; organising and staffing; and controlling and problem solving. Kotter states that leadership is different, it ‘does not produce consistency and order . . . it produces movement’ (1990: 4).

(Kotter 1990: 4)

In describing the ten roles of an effective manager, Mintzberg (1990) gave importance to the role of being a leader, by which he meant the setting of goals and assessing employee performance as well as mentoring, training and motivating employees.

More recently, the work of Heifetz (1994) has been influential in clarifying our understanding between management and leadership and has introduced an educational element into our definitions. Heifetz redefines leadership as ‘an activity rather than a position of influence or a set of personal characteristics’ (1994: 20). He proposes that we discard our ideas that ‘leaders are born and not made’ and that leadership becomes a learned quality, the teaching of which relates to learning how to help others to close the gap between solving technical problems (managerial skills) and problems arising in a complex, changing world in which the interdependence of environmental, societal and cultural factors is both part of the problem and the solution. Heifetz describes these latter factors as ‘adaptive’ and effective leadership as involving learning how to recognise the conditions that promote their emergence and how to help people address the challenges they face as they seek to resolve problems. Heifetz considered leadership as the capacity to adapt, to learn, to change, to narrow the gap between the past and the developing present, by creating energy, resources and ingenuity to change the circumstances.

‘I was appointed as a leader and therefore I already must have leadership skills’

From the seminal discussions of Kotter, Mintzberg and Heifetz, we can deduce that there are plenty of leaders who hold assigned positions yet lack leadership skills and there are plenty of people who are not formal leaders that show leadership skills. It is possible to be a leader yet fail to demonstrate leadership skills and at the same time possible to demonstrate leadership skills without a formal (structural) leadership position; leaders and leadership are not the same thing. The Oxford English Dictionary (2012) defines a leader as ‘a person who leads or commands a group, an organisation or a country’; taking that further, a person who takes the lead, an expert within his field or someone who is at the top of her profession. Leaders usually lead by example, from the front or the top of the hierarchy, and expect others to follow, frequently without discussion or group agreement.

Taylor and colleagues (2008) characterise effective leaders in academia as those who can identify with specific areas of academic or health professionals practice and ‘take the lead’ in developing themselves and taking others with them. Counter to that, leadership is a much more complicated concept and, for some, considered to be a collection of attributes. Bland and colleagues (1999) were some of the first to describe leadership as a collection of qualities when they presented a study of the leadership skills related to a successful university–community partnership. Their description of leadership included envisioning, collaboration, cooperation, communication, valuing systems and being able to set achievable goals. However, we have to understand in their study that they were looking at the subject through a more static or normative process, similar to the description of leadership provided by Lieff and Albert (2010, 2012). In their studies they divided best leadership practice into four domains of skill:

1 intrapersonal (role modelling, communication, envisioning);

2 interpersonal (valuing relationships, supportive, cooperative, collaborative);

3 organisational (facilitating change, having both a personal and shared vision, management of people and time);

4 systematic (organisational understanding, political awareness, societal need).

McKimm (2004), in her study of educational leaders, added other important qualities in the form of strategic and analytical thinking skills, personal development, self-awareness, risk taking, tolerance to uncertainty, and professional and contextual awareness.

It was Heifetz, though, who felt that these qualities were more qualities of a leader and leadership was something very different – ‘adaptive work’ (Heifetz 1994; Heifetz et al. 2009):

(Heifetz 1994: 22)

Adaptive work requires learning. The tasks of leadership consist of choreographing and directing the learning process in the organisation, institution or group. Leadership with or without authority requires an educative strategy.

‘Leaders are born leaders and therefore leadership cannot be taught’

Leadership is about knowing yourself and understanding others (Held and McKimm 2011) and in a complex environment the skills required for effective leadership are not inherent within the individual, nor do they come naturally. They need to be learned, understood and supported by theory; they need to be developed and evaluated. Those showing effective leadership also need to adapt to the ever-changing world of education and healthcare – i.e., show adaptive leadership (Heifetz and Linsky 2004). Medical and healthcare education in medical schools is complex (Sweeney and Griffiths 2002; Mennin 2013). Leadership within this complex environment requires careful and iterative navigation to learn about new policies, new strategies, financial and political systems and professional regulations. These are certainly not inherent in an individual – effective leadership has to be learned and practised.

Readers taking an interest in leadership will learn that there are many theories and models that underpin leadership. Describing all of these is beyond the scope of this chapter, but for more information, readers are directed to the relevant chapter by McKimm and Lieff in the 2013 book A Practical Guide for Medical Teachers.

‘I only manage programmes and therefore I do not need leadership skills’

The managers in medical schools are those individuals who are usually tasked to specific activities; to lead because of their academic or clinical experience or expertise. This has held true for many years. However, as medical education develops and medical curricula become more complex with competency-based education, integrated, community-based and interprofessional learning, electronic learning platforms and new methods of assessment, the managerial tasks themselves also become more complex. Northouse (2004) in describing leadership considered that managers produce order and consistency, while leadership is about producing change, direction and movement. John Kotter (1999) identified the need for two distinct and complementary systems to deal with the complexity of institutions; he called for both management and leadership, with leadership being a learned skill that complements management. He based this upon his observation that many institutions were indeed over-managed – too many people making decisions but not in a coherent or purposeful direction, eventually leading to fragmentation and ineffective learning. Leadership provides the vision for change that leads the institution in a coherent direction for learning and working together. However, in reality, it is more appropriate that they both blend into one another – the manager assuming more leadership skills, whilst leadership per se envelops being a manager, depending on the situation. Charles Handy (1993) draws a relevant analogy in his work describing organisations. He likens a manager to a general practitioner (GP) dealing with a patient – the first point of call for a problem that requires an answer. In doing that the GP uses four basic actions:

1 symptom identification;

2 diagnosis;

3 decision regarding appropriate management;

4 management of the patient.

Leadership at a college or regulating body level provides direction and vision. Much has changed from the date of this analogy. The workings within a 21st-century healthcare system often place more responsibility on the manager, in terms of responsibility and accountability, and they tend towards a manager also requiring leadership skills.

From theory to practice

So far this chapter has discussed the concept of leadership, management and leaders as individual concepts that in the complex worlds of healthcare and medical schools frequently overlap in definition and roles. Theory is of limited relevance without practice. Now we turn to examples of some of those definitions and theories in practice through three different models of leadership and management from three medical schools.

Case study 22.1 Recognising leadership, management and other responsibilities within the medical school – an example from Pakistan

Rukhsana W. Zuberi and Farhat Abbas

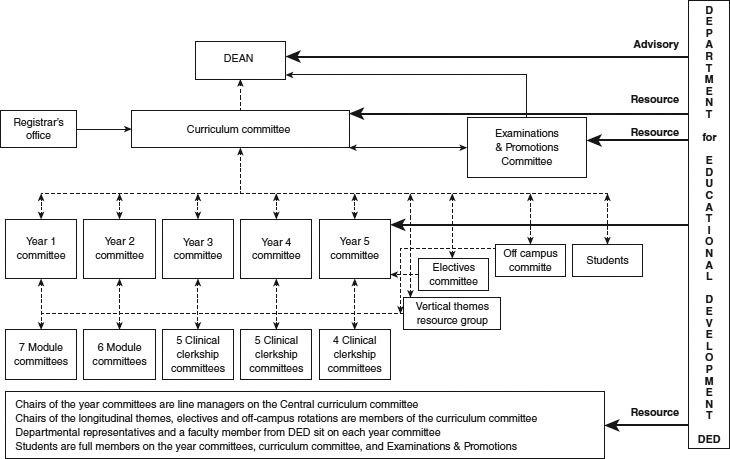

Aga Khan University (AKU), Pakistan, is a renowned, internationally recognised private academic institution. The Medical College admits 100 students per year in a 5-year curriculum. The Curriculum Committee (CC), the responsible academic body for undergraduate medical education (UGME), reports directly to the Dean. The curriculum has been systems-based from its inception, with department heads and students as UGME-CC members.

Organisational structure within AKU Medical College

A curriculum review by the Department for Educational Development (DED) in 1999 recommended an integrated, outcome-based curriculum. As the curricular framework developed, the curriculum management structures were aligned to it in order to sustain the change. In 2002, the Mintzberg strategy for planning and management was instituted with the renewed curriculum (Mintzberg 1992, 2009). Decision-making power became centralised in the UGME-CC. Through its subcommittees for the different phases and elements of the curriculum, authority was devolved to those responsible for curricular planning, delivering and monitoring.

Curriculum committee

The UGME-CC chair held a Masters in Health Professions Education (MHPE – Maastricht University) qualification. The two co-chairs represented basic and clinical sciences. Multidisciplinary teams were organised to plan, coordinate, implement and evaluate the longitudinal themes, which cut across all 5 years of the curriculum. These coordinators had access to all Year Committees and were members of the CC. There were two student members on UGME-CC: one from Year 1 or 2 and one from Year 5. There was a student member on each Year Committee. A curriculum office with its own budget was created.

Examinations and Promotions Committee

AKU is accountable to society and its community for the quality of its medical graduates. The Examinations and Promotions (E&P) Committee is chaired by a faculty member with demonstrated interest in medical education. Membership includes four faculty members, with no responsibility towards any phase of the curriculum, and two Year-5 students. All student members on all educational committees are full members and are elected by the students.

Cross-representation

To ensure cross-representation, the chair of the UGME-CC is a member of the E&P Committee and vice versa. The Associate Dean of Education (also chair of the DED) and the Senior Associate Registrar are members of both the UGME-CC and the E&P Committee.

The DED is responsible for the philosophical underpinnings of educational programmes and for all examinations. It focuses on improving curricula, pedagogy, use of e-learning, web-based resources and assessments. The DED leads self-studies for programme evaluations. All DED faculty members have or are in the process of acquiring a Masters or PhD in Health Professions Education (HPE). The DED has membership on all Year Committees, the UGME-CC and the E&P Committee (Figure 22.1).

Faculty members aspiring towards careers in medical education were recruited for joint appointments between the DED and other clinical/basic science departments as educational coordinators. They facilitate the implementation of educational principles, philosophies and policies in the other departments and assure quality.

The DED offers a 5-day Introductory Short Course in Health Professions Education mandatory for all new, incoming faculty members. It offers retreats, workshops and courses and has recently initiated a Master’s degree in HPE for developing researchers and leaders. It is a resource in medical education for other national institutions as needed.

(Acknowledgements to Dr Zoon Naqvi, Dr Rashida Ahmed and the late Dr Robert Maudsley.)

What can be learned from the Aga Kahn case study?

• Initially, the curricular review by the DED recommended an integrated outcome-based curriculum. Before work began they decided upon a recognised theory of organisational management; they demonstrated leadership through vision and organisational skills by adopting a valid and well-tested approach to organisation management – the Mintzberg matrix of organisational management.

• Although major decision-making power became centralised in the UGME-CC, there was a planned devolution of tasks to appointed subcommittees and named individuals – collaboration and cooperation.

• New skills required in modern medical education were agreed – the UGME-CC chair already had a recognisable higher qualification and there was support for others to follow, supporting the workforce.

• A multidisciplinary team approach was instituted, creating equity, cooperation and coordination.

• There appeared to be a shared understanding of the curriculum, achieved through a defined organisational structure, enhanced through integration and equal access to all elements of the curriculum – effective communication skills.

• Student engagement in the process and social awareness ensured a cooperative and shared process.

• There was a willingness to share educational skills within society through educational courses.

• Creating a separate budget for the curriculum office allowed financial flexibility, but also delegated responsibility.

• The level playing field that appears to exist in the managerial structure supports both a top-down and a bottom-up approach, where all involved are allowed a say and shared vision within the curriculum.

• The DED is positioned to recognise and respond to the need for change – an important issue in the changing world of medical education.

• The whole process was structured around need: the need in 1999 for curricula renewal in the medical school, set within a specific environment using modern methods of medical education.

Case study 22.2 Starting a new medical school in Southern Africa – University of Namibia Medical School

Jonas Nordquist

Namibia and the lack of health professionals

The World Health Organization (WHO) demonstrated, in its 2006 World Health Report, the urgent need to train health professionals in all parts of the world, and this was specifically critical in Africa (WHO 2006). This case addresses the leadership challenges when starting a new medical school in Namibia, a country previously dependent upon graduates from other countries and whose indigenous students frequently failed to return to their mother country.

Namibia is a middle-income country in Southern Africa with a population of approximately 2.3 million. Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)/acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS), tuberculosis and other infectious diseases threaten the population, as well as its economic development.

In a national comprehensive vision from 2004 (Namibia Vision 2030: Republic of Namibia 2004), a number of actions were identified to improve the health system and health education. Focus was needed on training medical and paramedical personnel, with a focus on rural and community health and the prevention of HIV/AIDS. Primary care was highlighted as a priority area.

The birth of the first Namibian School of Medicine

In 2009, a five-person taskforce of national and international members was appointed with the mission of designing a new medical school in only 5 months, with content, curricula, admission, recruitment of staff, and the design of the new infrastructure all being addressed. In parallel, the recruitment of faculty and students was organised at a central level within the University of Namibia – in effect, three parallel processes conducted by two separate groups.

One of the central challenges was to select an appropriate curriculum model. Due to the short time span, familiarity with the systems and similar pattern of diseases, the taskforce looked into curricular models in the region. A 5-year undergraduate curriculum, mainly based on the classical pre-clinical and clinical Flexnerian model, was chosen, but with a strong emphasis on active learning.

The school officially opened in August 2010, admitting 59 out of 750 applicants. Even though the infrastructure was not yet completed at that time, a lot of emphasis was placed on designing a new medical school where the physical infrastructure would align with the curriculum and also reflect the underlying values of the new school (Nordquist and Sundberg 2013): a vibrant, inviting and dynamic place, where colours and materials should be Namibian and mirror the needs of Namibia. The buildings had also to be designed for hybrid curricula, with small tutorial rooms, labs, lecture theatres, IT suites and seminar rooms. Health professionals in fields other than medicine (pharmacy, dentistry and physiotherapy) will in the future also be graduating from new schools developed and developing within the university.

Planning is crucial and must be given more time than just a few months, but, in this case, the political urgency to start a new medical school made this impossible. The relationship with and expectations of the Ministries of Health and Ministries of Education concerning universities is an interesting and sometimes delicate political issue. There is also a need to create alignment between different planning processes, and taskforce members should ideally represent different disciplines and stakeholder interests; in particular, it is of great importance to include clinicians and the potential providers of clinical rotations into this process at a very early stage. Another important lesson is to develop a local vision of the enterprise of a new medical school that can guide all the different taskforces and groups involved in setting up the new medical school. There is an obvious risk that many decisions otherwise will be based on different mental models that have not been made explicit. If there are different groups involved (as in this case), one might run into a situation where different groups have different mental models or ideas about the new medical school. This is not productive and leads to miscommunication. Mistakes and such miscommunication can be avoided if local visions are created and expressed by groups involved. Many decisions might also be made on technical grounds, with no alignment with the overall vision of the new medical school. If possible, local visions (if they are properly developed) should strive for alignment with other national and international strategies.

The curricula developed have to honour the local needs, both in terms of content and its implementation. Everything has to be localised – a simple copy-and-paste strategy doesn’t work. Also, the physical design of a new medical school is a strategic decision and has to align with the ideas behind the curricula. The development of the new medical school in Namibia demonstrates this.

What important features can be learned from the University of Namibia case study?

• This case study differentiates the roles and responsibilities of leader, leadership and management.

• The political leaders decided on the development of an urgently needed medical school – a poorly thought-out but socially necessary activity.

• Leadership was sought by the selection of national and international experts within their field.

• Leadership skills in planning, discussion and communication with the political leaders overcame the initial barriers.

• Compromise was made in adopting a more traditional yet achievable curriculum, rather than reaching for unobtainable heights in curriculum design.

• Inclusivity was a feature of early discussions, with early involvement of all those connected with the curriculum.

• Parallel processing of essential activities, associated with delegation and responsibility of tasks, reduced the time factor to completion, appointing managers with designated roles and delegated responsibilities.

• The leadership had a particular vision of the medical school which encapsulated the needs of the students, faculty and society in planning the school.

• Expertise in design matched the curriculum style, the students and national and local needs, even to the level of using the national Namibian colours, all achieved through vision, expertise and effective communication.

• Cohesion of thought and activity pervades the planning, development and delivery of the medical school.

• Despite the political pressures and the problems created, adaptive leadership brought about change.

Case study 22.3 Steps towards establishing a new medical college in Saudi Arabia – an insight into medical education in the Kingdom

Khalid A. Bin Abdulrahman and Farid Saleh

Medical education in Saudi Arabia has evolved since the late 1960s when the first medical college was established and named after the late King Saud Bin Abdulaziz. Four other medical colleges were later developed and these five remained the only colleges graduating doctors for the next 30 years.

In 2006, the country’s statistics showed that the percentage of Saudi nationals holding a medical degree and practising in the public health sector was less than 20 per cent. This alarming figure necessitated the issuing of a royal decree by King Abdullah bin Abdulaziz Al-Saud, the Custodian of the Two Holy Mosques, and the Chairman of the Council of Ministers and Higher Education Board to develop and expand medical education in the Kingdom. It resulted in the establishment of many new medical colleges and expansion of some of the existing ones. There are currently 28 public and six private medical colleges in the Kingdom, with five more public colleges on the verge of being established in the near future.

The College of Medicine at Al-Imam Mohammad Bin Saud Islamic University was founded in 2007 and became operational during the academic year of 2008–9. The vision was to help in revolutionising medical education in the Kingdom and graduate medical doctors who demonstrate those skills required of a doctor equipped for the 21st century. To achieve this goal, careful and lengthy planning, testing and retesting followed. Despite the urgent need to establish new medical colleges in the Kingdom, careful considerations were made in order not to compromise the time that should be allocated to each of the developmental steps while planning the establishment of the College of Medicine at Al-Imam University. The main goal that was kept in mind, and subsequently integrated in all these steps, was innovation in medical education. Soon after the appointment of a founding dean, a subcommittee derived from the Saudi Medical Colleges Deans’ Committee was created and chaired by the founding dean. It included the deans of three new medical colleges. The main goal of the subcommittee was to review the status of medical education in the Kingdom and to produce a list of fundamental steps to be followed by any new medical college to be established in the country.

An important cornerstone in establishing a new medical college is the appointment of a founding dean, who should have an excellent background in medical education and leadership, management and communication skills. These skills are essential for surveying medical education nationwide; communicating a unique vision, missions, goals and objectives pertaining to the new medical college; providing leadership in the implementation of these missions, goals and objectives; and acting as a catalyst for securing the resources needed for the proper accomplishment of the various tasks. In addition, the founding dean should have the expertise in planning, developing, evaluating and implementing medical and allied health curricula.

The recommendations made by the subcommittee included the need for the medical college to take into consideration, right from the beginning, both institutional and programme accreditation, based on international and national standards and requirements. To achieve this goal, five main pillars of a medical college were planned by the six main taskforces, headed by the founding dean. These five pillars were: the setting of the institution; the medical programme; the student division; the faculty division; and the resources needed. The sixth taskforce was a liaison committee, whose role was to accumulate and share information and activities derived from the other five main task forces. Embedded among the five pillars are 21 domains, which include administration and governance, the academic environment and the programme’s essential elements, namely curriculum management, objectives, design, content, teaching, evaluation and the learning environment.

Other domains embedded in the five pillars pertaining to students are their admission and selection criteria, premedical requirements, counselling, and ethical and professional conduct. Still other domains embedded in the five pillars and pertaining to the teaching staff (both faculty and teaching assistants) include their number, experience and qualifications. The last domain pertains to the finance, space, clinical affiliations, information technology, support staff, library and other educational resources. Planning for the domains listed above was allocated to the six main taskforces described earlier, based on the pillars to which these domains belong. The recommended action plan towards establishing a new medical college in the Kingdom, along with the suggested timeframe, is summarised in Table 22.1. Moreover, the new medical college was designed with the healthcare needs of the community and region in mind, and to increase the supply of well-qualified physicians who are compassionate and who will be inclined to practise in the community and region, and enhance the academic standing of the university to which it belongs. The latter should facilitate the new establishment process by bypassing bureaucracy and by considering the new college as a ‘newborn baby’ that requires special attention and care for 5 years following its birth.

Table 22.1 Development action plan: the College of Medicine at Al-Imam Mohammad Bin Saud Islamic University

Administrative affairs

• Founding dean and job description – first 6 months

• Vice-deans – first 6 months

• Executive secretary – first month

• Director of staff affairs – first month

• Supervisor of student affairs – first month

• Calculation of costs – first 3 months

• Formal delineation of the relationship between the medical college and the parent university

• Director of finance – first 3 months

Admission and enrolment of students, and other student affairs

• Conditions and regulations for student admission – first month

• Maximum and minimum number of students – first month

• Written procedures and standards for the evaluation, progress, counselling and graduation of students and disciplinary actions

Faculty affairs

• Number, qualifications, experience and specialties of faculty members – first 6 months

• Medical education specialist – first 2 years

• Faculty development program – first year

• Teaching assistants – first year

Curriculum

• Mission statements – first 3 months

• Objectives and outcomes – first 3 months

• Competencies – first 3 months

• Preparatory year – first 3 months

• Pre-clinical and clinical years – first year

• Internship year – first 2 years

• Delivery methods

• Assessment methods

Educational environment and infrastructure

• Temporary college administration building – first month

• Space needs for the preparatory, and pre-clinical and clinical years – first 2 and 6 months, respectively

• Design of the university hospital – first year

• Cooperation agreements with regional health sectors – first 2 years

• Learning resources within and outside the college, including the library and information technology – first 6 months

Temporary college board

• Nominating the members – first 2 months

• Nominating the secretary – first 2 months

What important features can be learned from the Saudi Arabian case study?

• The decision to establish a new medical school was based on societal and national needs, and supported by a forward-thinking political ideal.

• A structured approach to planning and development, although it may take time and resources, led to a successful outcome.

• The appointment of a founding dean with specific qualifications in medical education and with leadership skills was one of the first priorities in the schools development.

• Early communication with other medical schools, enhancing collaboration and cooperation, was essential to develop a series of schools that all had the same important vision – the development of high-quality institutions tailored to the needs of the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia.

• A clear definition of the mission of the school and a very clear plan of its organisational structure enabled a shared understanding of what the school was aiming to be and to achieve.

• The school used the accreditation process, through which it would pass in the future, as a template for curricular construction.

• The detailed plan allowed a clear vision and definition of the roles and responsibilities of all those involved in the medical school, supporting effective management and responsibility.

• A realistic timeframe underpinned the development plan.

The role of the medical school and medical education is paramount in today’s complex world. They are at the heart of producing doctors equipped to deliver high-quality healthcare for the 21st century and beyond. Whereas history has supported the top-down ‘leader’ model of management, contemporary challenges have necessitated the development of a new approach to institution leadership and management. Those tasked with taking charge of medical schools are required to develop diverse and essential skills, most of which have to be learned, developed and adapted over time and adapted to changing circumstances. These skills, under the broad umbrella of leadership, should now take priority over the previous political and academic qualities expressed by past leaders of medical schools, and used as a basis for appointment.

Medical education is rapidly evolving; new styles and forms of medical schools are fast developing; societal pressures demand a new style of healthcare; effective leadership is at the fore.

Take-home messages

• Medical schools are complex environments requiring effective leadership and management.

• Confusion occurs between the terms leadership, management and leader; clarity of these terms is important.

• Previous definitions of leadership do not accommodate the complex world of institutional organisations.

• Adaptive leadership is a more appropriate style, requires a change in values, beliefs or behaviour and is an educative process.

Bibliography

Bland, C.J., Starnaman, S., Hembroff, L., Perlstadt, H., Henry, R. and Richards R. (1999) ‘Leadership behaviours for successful leadership–community collaborations to change curricula’, Academic Medicine, 74(11): 1227–37.

Boelen, C., Gibbs, T. and Dharamsi, S. (2013) ‘The social accountability of medical schools and its indicators’, Education for Health, 25(3): 180–94.

Department of Health (2002) Learning from Bristol: the Department of Health’s response to the report of the Public Inquiry into children’s heart surgery at the Bristol Royal Infirmary 1984–1995, London: The Stationery Office. Online. Available HTTP: https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/273320/5363.pdf (accessed 24 March 2015).

Glouberman, S. and Zimmerman, B. (2002) Complicated and complex systems: What would successful reform of Medicare look like?, Canada: Commission on the Future of Health Care in Canada.

Hamilton, P., Spurgeon, P., Clark, J., Dent, J. and Armit, K. (2008) Engaging doctors: Can doctors influence organisational performance? London: NHS Institute for Innovation and Improvement and Academy of Medical Royal Colleges.

Handy, C.B. (1993) Understanding organisations, London: Penguin.

Heiffetz, R.A. (1994) Leadership without easy answers, Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press.

Heifetz, R. and Linsky, M. (2004) ‘When leadership spells danger’, Educational Leadership, 61(7): 33–7.

Heifetz, R., Grashow, A. and Linsky, M. (2009) The practice of adaptive leadership: Tools and tactics for changing your organization and the world, Boston, MA: Harvard Business Press.

Held, S. and McKimm, J. (2011) Emotional intelligence, emotional labour and effective leadership. In M. Preedy, N. Bennett and C. Wise (eds) Educational leadership, context, strategy and collaboration, Milton Keynes: The Open University.

Jonas, S., McCay, L. and Keogh, B. (2011) The importance of clinical leadership. In T. Swanick and J. McKimm (eds) ABC of clinical leadership, Oxford: BMJ Books/Wiley-Blackwell.

Kotter, J.P. (1990) A force for change: How leadership differs from management, New York, NY: The Free Press.

Kotter, J.P. (1999) What leaders really do, Boston, MA: Harvard Business School Press.

Lieff, S. and Albert, M. (2010) ‘The mindsets of medical education leaders: How do they conceive of their work?’, Academic Medicine, 85(1): 57–62.

Lieff, S.J. and Albert, M. (2012) ‘What do I do? Practice and learning strategies of medical education leaders’. Medical Teacher, 34(4): 312–19.

Long, A. (2011) Leadership and management. In T. Swanick and J. McKimm (eds) The ABC of clinical leadership, Oxford: BMJ Boooks/Wiley-Blackwell.

McKimm, J. (2004) Special report 5: Case studies in leadership in medical and health care education. York, UK: The Higher Education Academy.

McKimm, J. and Lieff, S.J. (2013) Medical education leadership. In J. Dent and R.M. Harden (eds) A practical guide for medical teachers, Chapter 42, London: Churchill Livingstone–Elsevier.

Mennin, S. (2013) Health professions education: Complexity, teaching and learning. In J.P. Sturmberg and C. Martin (eds.) Handbook of systems and complexity in health (pp. 755–66). Heidelberg: Springer.

Mintzberg, H. (1973) McGill University School of Management, The nature of managerial work, Canada: Harper and Row.

Mintzberg, H. (1990) Mintzberg on management, New York, NY: The Free Press.

Mintzberg, H. (1992). Structure in fives: Designing effective organizations, Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Mintzberg, H. (2009) Tracking strategies: Toward a general theory of strategy formation, New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Nordquist, J. and Sundberg, K. (2013) ‘An educational leadership responsibility in primary care: Ensuring the physical space for learning aligns with the educational mission’, Education for Primary Care, 24(1): 45–9.

Northouse, P. (2004) Leadership: Theory and practice (3rd edn), London: Sage Publishing.

Oxford English Dictionary (2012) Online. Available HTTP: www.oed.com (accessed 28 December 2014).

Republic of Namibia (2004) Namibia Vision 2030 policy framework for long-term national development. Windhoek: Office of the President.

Sweeney, K. and Griffiths, F. (2002) Complexity and health care: An introduction. Abingdon: Radcliffe Medical Press.

Taylor, C.A., Taylor, J.C. and Stoller, J.K. (2008) Exploring leadership competencies in established and aspiring physician leaders: An interview based study, Journal of General Internal Medicine, 23(6): 748–54.

Thygeson, M., Morrissey, L. and Ulstad, V. (2010) ‘Adaptive leadership and the practice of medicine: A complexity-based approach to reframing the doctor–patient relationship’, Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice, 16(5): 1009–15.

World Health Organization (2006) World health report. Geneva: WHO. Online. Available HTTP: http://www.who.int/whr/2006/en/ (accessed 28 December 2014).