HOW TEACHING EXPERTISE AND SCHOLARSHIP CAN BE DEVELOPED, RECOGNISED AND REWARDED

The teacher is one of the most powerful assets of a medical school. Content expertise is not the same as teaching experience.

Every day, in every part of the world, medical students and postgraduate trainees are engaged in learning to be physicians. Educators have been teaching the sciences fundamental to the understanding of health and disease (e.g. anatomy, physiology) since antiquity, when clinical educators/physicians like Hippocrates travelled around Greece to train medical students (Grammaticos and Diamantis 2008). Indeed as Aristotle said, ‘Teaching is the highest form of understanding’, and begins with what the teacher knows – the subject matter of the teacher’s field (Boyer 1990). Yet teaching is more than transmitting knowledge from one’s discipline; it requires a dynamic synergy between one’s knowledge of subject matter and skills as a teacher. The latter requires a knowledge of the principles of learning, educational methods, instructional resources and knowledge of learners (Irby 1994).

On a daily basis, teachers systematically approach their task by:

1 identifying clear goals for their teaching interactions;

2 assuring that they are adequately prepared (current in their subject and as teachers);

3 selecting the appropriate methods for teaching and assessment with attention to delivery platforms (e.g. classroom, clinical rotations, community, web/online), and possible approaches to meet their goals within the time/resources available (e.g. lectures, podcasts, small-group discussions, simulations, multiple-choice assessments);

4 analysing the results to determine the extent to which learning occurred;

5 sharing those findings with colleagues (e.g. course leaders, curriculum committees, other educators); and then

6 critically reflecting on their efforts in order to revise and improve, in preparation for the next educational event (Glassick et al. 1997).

This stepwise, systematic approach to how educators approach their work is synonymous with what it means to be a ‘scholar’. Scholars in all fields – be it scientists seeking discoveries, community health officials seeking the root cause(s) for a disease outbreak or teachers seeking to prepare and certify our next generation of healthcare professionals – approach their tasks by beginning with clear goals and adequate preparation and conclude with reflective critique.

The work of educators goes beyond the ‘act’ of teaching. Educators are involved in at least four additional domains of activities, each requiring a scholar’s approach: curriculum development; advising/mentoring; learner assessment; and/or educational leadership/administration (Simpson et al. 2007). While educators typically approach their work using elements associated with a scholar’s approach (e.g. clear goals = defined objectives linked to competencies), the rigor and value of this work often go unrecognised and undervalued. The criteria associated with a scholar’s approach in each of these five educator activities have been elucidated through a systematic, evidence- and stakeholder-based process and can be used to frame educator development initiatives and processes for educator recognition/reward decisions (Gusic et al. 2013, 2014). Explicitly framing our educational work as the work of educational scholars allows us to identify and address gaps in our scholarly approach and stand as equals with our research colleagues.

How do we begin?

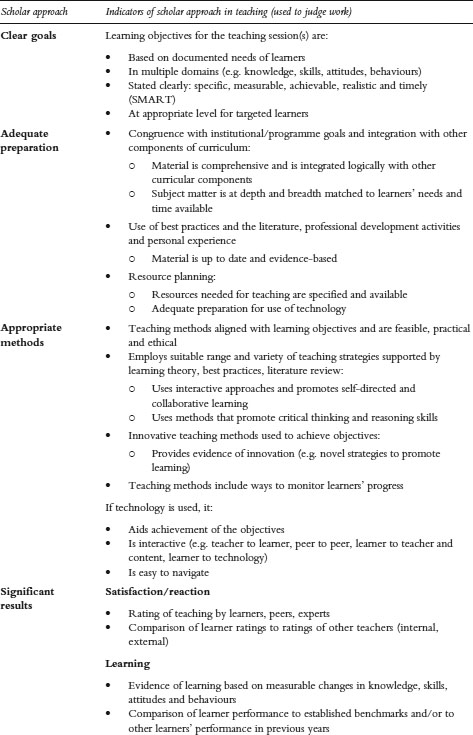

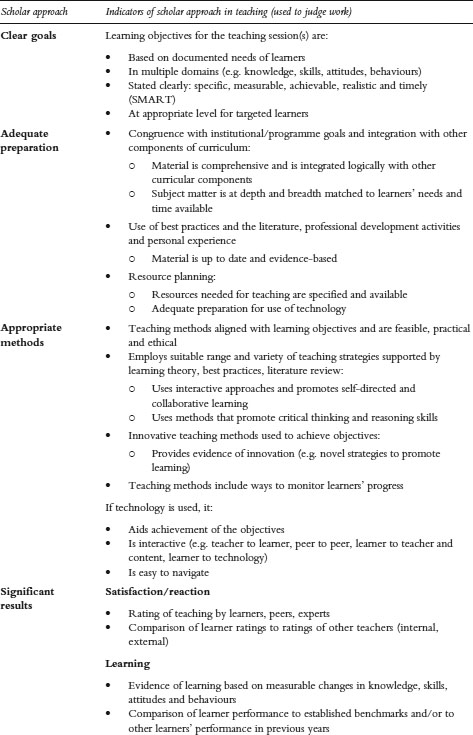

First we present the educator-as-scholar framework (Gusic et al. 2013) and then we illustrate its application for individual and programmatic faculty development and for recognition and reward of educators through several case studies. The scholar framework uses a common structure to ascertain the degree to which we engage in, and can demonstrate, the value of our work as educators (Table 23.1): the first column presents the stepwise approach used by scholars in any field, and the second column provides both broad and specific quality indicators that can be used for assessment of one’s work as an educator. Independent of the domain of educational scholar activity (e.g. teaching, curriculum, learner assessment), the framework is consistent: the necessary steps are listed in the first column. Indicators related to significant results are adapted from Kirkpatrick and Kirkpatrick’s (2006) four-level model for measuring the outcomes of training programmes (satisfaction/reaction, learning, application of learning, impact). The effective presentation indicators are outlined using accepted standards for scholarship across all fields, as outlined by Hutchings and Shulman (1999): scholarly work must be reviewed by peers and shared with others/disseminated in a format that others can use or adapt. To see the broad and detailed indicators for each of the other educator activities (e.g. curriculum, advising/mentoring, learning assessment, administration/leadership), access is available through MedEdPORTAL, a peer-reviewed repository of educational materials (Gusic et al. 2013).

Illustration of scholar approach in four case studies

To demonstrate how the scholar approach works to transcend differences in our institutions and organisations, we apply the approach to several case studies with four objectives; that is, to demonstrate how this framework can be used to:

1 provide guidance to medical educators who are teaching multiple learners, in a variety of settings (e.g. classroom, community, health system);

2 identify needs and inform the design of faculty development efforts;

3 assess the quality of our work as educators;

4 return educators to be amongst those who, like Hippocrates, are recognised and esteemed.

While each of the six scholar elements outlined in Table 23.1 can be identified in each case, we will highlight several elements within each of the first two cases, allowing a richer illustration of the approach, and then offer a combined analysis for the last two cases, to provide an integrated perspective.

Table 23.1 Scholar framework – broad and specific indicators for teaching activities

Source: Adapted from Gusic, M.E., Baldwin, C.D., Chandran, L., Rose, S., Simpson, D., Strobel, H.W., Timm, C. and Fincher, R.M. Academic Medicine 2014, 89(7):1006-11; and Gusic, M.E., Amiel, J., Baldwin, C., Chandran, L., Fincher, R., Mavis, B., O’Sullivan, P., Padmore, J., Rose, S., Simpson, D., Strobel, H., Timm, C. and Viggiano, T. (2013) Using the AAMC toolbox for evaluating educators: You be the judge!, MedEdPORTAL. Online. Available HTTP: www.mededportal.org/publication/9313 (accessed 6 August 2014).

Case study 23.1 Dr Lasz Lo – clinician teacher (teaching activity category)

A practising physician employed by a large non-profit healthcare system in the USA, Dr Lasz Lo regularly has students and residents rotating with him on his hospital rounds and in clinic. He enjoys the opportunity to teach and feels it is his duty to give back because of his respect for those who trained him. Dr Lo often spends extra time to learn about trainees as people and provide guidance to them as future physicians.

‘Medicine’, Dr Lo often tells his learners, ‘is the highest calling one can have. . . Our patients trust us to help them stay well, to care for them in time of need, and to treat them as our equals. We must never violate that trust.’ Dr Lo has high expectations for himself and for his learners specifically because he often cares for the neediest of patients. Many of Dr Lo’s patients are poor (choosing to spend their limited funds on housing and food for their families rather than medications) and suffer from multiple chronic conditions, even those at a young age. Patients often struggle to get to his clinic because transportation options are limited. Time for teaching, given this complex patient population, is limited, as he is often running ‘behind’. The healthcare system encourages teaching, but its first priority is patient care, providing regular reports to Dr Lo about his performance on various quality and safety measures.

Recently, Dr Lo was contacted by the physician who supervises the healthcare system’s student education. According to the supervisor, students have been reporting for the last year that Dr Lo is disorganised (e.g. their start time with him is unpredictable, their roles are unclear); interrupts students as they present cases; has unrealistic expectations for what they can do at their stage of training; and doesn’t tell students what they are supposed to learn. Dr Lo is shocked! He had always been told that he was a good teacher. Dr Lo is angry and frustrated that his students never talked to him about their concerns and that this was the first time he had learned that this was a problem. Demoralised, Dr Lo wonders if he should continue to teach as he doesn’t have time to spend ‘reading’. His teaching already takes time away from his patients and his family. The supervisor, who doesn’t want to lose Dr Lo as a clinical preceptor, sits down with Dr Lo to share strategies about how he might enhance his work with learners.

Providing guidance to educators

Clinical teachers like Dr Lasz Lo have an extraordinarily difficult task: to assure the highest quality of care for their patients and to teach learners who expect high-quality education in a dynamic, fast-paced setting. Applying the teacher–scholar framework can provide Dr Lo and his supervisor with specific guidance to improve teaching. The analysis below represents the approach the supervisor can use in working with his colleague, Dr Lasz Lo.

Clear goals

Students, teachers and supervisors at clinical sites must have an agreed-upon set of SMART learning objectives for the experience. These objectives must be explicit and shared with both the teacher and the learner so that each has the same expectations for the experience.

Adequate preparation

Annually, supervisors should ensure that the unit and the teachers are ready to teach by working with teachers to:

1 confirm that teachers and learners have shared these goals and agree that they are attainable within the time available;

2 delineate specific roles and responsibilities for all students rotating through the department that are aligned with expectations for their stage of training;

3 match any assignments for students to the goals for the rotation, roles and responsibilities;

4 provide teachers with a brief (3–5 minute) ‘teaching script’ to use in orienting learners to their teams and to their roles/expectations. The supervisor can use existing resources and templates widely accessible on the web to adapt to the system/setting as resources for teachers.

Healthcare teams and their members function most effectively and efficiently when: they have shared values (to provide the safest and highest quality of care possible); they have clear roles and responsibilities (e.g. students are responsible for . . . ); and members accept accountability and perceive that the team leader will create a safe and respectful environment in which any team member (even a student who feels at the lowest rung on the ladder) can raise a concern or question. The supervisor can help Dr Lo and other teachers create an environment that promotes learning, by sharing strategies to meet teaching goals. Examples include:

1 a 10–15-minute orientation when the ‘team is formed’ (e.g. when a medical student begins the rotation) that reaffirms the team’s shared values, members’ roles and responsibilities and accountabilities;

2 ‘activity of daily living’ schedules and templates for students to provide clear structure (e.g. start at 7:00 a.m.; case presentation for inpatient versus outpatient; map of facility; and team call numbers). Start simply, adding an element or two for each rotation so that students do not become overwhelmed with these tasks.

Case study 23.2 Supporting the continuum of faculty development through the Department for Educational Development, Aga Khan University, Pakistan

Aga Khan University (AKU) is a not-for-profit private university with campuses in Asia, East Africa and the UK. A School of Nursing was established in 1982, followed by establishment of the Medical College in 1983. Faculty members are recruited for their specialty-based expertise, but generally need support to enhance their teaching expertise. In response to this need, the Department for Educational Development (DED) was created to support faculty as teachers and scholars through programmatic interventions ranging from individual consultations, to serving as educational experts on academic committees, conducting workshops and annual retreats, and administering certificate and graduate degrees in health professional education (HPE). DED faculty have Masters or doctoral-level qualifications in Medical Education/HPE from the University of Illinois at Chicago, University of Calgary, Dundee University, University of Leeds, Cardiff University, University of Maastricht, University Ambrosiana and AKU, bringing together global perspectives for diversity and enrichment.

A one-credit course, ‘Introductory Short Course in HPE – Theory to Practice,’ is mandatory for all newly recruited AKU Faculty of Health Sciences faculty members and a prerequisite for other DED courses and graduate programmes. It focuses on trends in curriculum development, teaching/learning methods and resources, and the principles of learner assessment and monitoring. Advanced Masters-level courses are offered in curriculum development, teaching/learning, assessment, programme evaluation, leadership and research in HPE to prepare teachers, educators, researchers and leaders nationally and for the region. Coordinators and directors of academic programmes are encouraged to take the ‘teaching/learning’ and ‘assessment’ courses.

Faculty members may take any of these components as free-standing courses to improve teaching expertise or all courses to obtain diploma/degree qualifications in HPE. Faculty members who wish to be educators or spearhead academic programmes have the opportunity to complete the requirements for the Advanced Diploma or Master of HPE degree.

Evidence of excellence and/or scholarship in teaching, discovery, integration and/or application serves as the basis for university-wide teaching awards, academic promotion, appointments to academic leadership positions and nominations for national awards, including the Pride of Performance Award from the Higher Education Commission.

Through its work with medical schools, accrediting and regulatory bodies, DED has brought about educational reforms and influenced national undergraduate and postgraduate curricula and policies.

Addressing needs for faculty development creates academic educator career path(s)

Faculty development for educators must be designed to meet institutional needs and be aligned to support academic career trajectories. Applying a systematic process, AKU created the DED and its programmes to enhance and reward faculty members’ skills as teachers and as educational leaders and administrators.

Clear goals

The requirement that all faculty complete a basic education course establishes that education is a discipline requiring training and expertise. The multiple types and levels of programming provided by the DED allow faculty and coordinators to select the opportunities that are best suited to meet their needs and professional goals as educators.

Adequate preparation

Faculty in the DED are experienced educators who have pursued advanced professional training in diverse settings. This expertise allows them to share best practices, approaches from the literature and personal experience in their work with faculty members from national institutions to support programmatic improvement. Their knowledge and skills as educators also ensure that the educational programmes are designed to meet national health priorities and the learners’ educational needs, and are aligned with institutional goals.

Appropriate methods

Multiple venues, formats and progression levels (e.g. certificate, degree) provide faculty with a flexible approach to developing educational expertise needed to meet their career goals. Over a period of 25 years, the DED has served as a catalyst in establishing and sustaining institutional recognition and reward structures for education at each stage of a faculty member’s career.

Case study 23.3 Institution(alising) education in a healthcare system, Singapore

Singapore Health Services (SingHealth) is the largest public health cluster in Singapore serving as a clinical service-focused healthcare system, providing clinical education supported by outstanding educational role models and numerous faculty development programmes. Educational scholarship, however, was not well integrated with clinical care and research. In 2011, SingHealth’s interest in integrating educational scholarship with its clinical care and research initiatives resulted in the creation of a ‘functional ecosystem in the form of an Academic Healthcare Cluster’ with Duke-National University of Singapore Graduate Medical School in Singapore (Krishnan and Ng 2012). An Academic Medicine Education Institute (AM.EI) (www.academic-medicine.edu.sg/amei/) was established in 2012 to provide resources to support clinical educators’ academic efforts in education; to integrate and coordinate faculty development programmes; and to develop a community of scholarly clinician educators to influence the overall education culture of the institution. Open to all healthcare professionals, from trainees to experienced teachers, AM.EI merges a teaching academy concept with comprehensive faculty development and career mentoring/advising to advance educational scholarship at all membership levels (Associate, Full, Fellow, Scholar).

The AM•EI has established three workgroups (Advocacy, Professional Development and Scholarship) that facilitate and support the institute’s goals. For example, the Advocacy workgroup identifies and recognises excellence in educational efforts; defines promotion criteria for health professions educators; and supports efforts to improve education. The workgroup has developed an educator portfolio framework based on the key domains for the Academy of Medical Educators (www.medicaleducators.org)) competencies (designing and planning learning; teaching and supporting learners; assessment and feedback; educational research; educational management and leadership as core values). The portfolio is now a required component for our Appointments, Promotions and Tenure committee for all educators. An annual Golden Apple Award system has been established to recognise teaching excellence, innovation and creativity. The Professional Development Workgroup has established 17 Academy of Medical Educators domain-focused professional development workshops offered two to three times per year, a monthly Medical Education Grand Rounds series and three education fellowships (one year or more in length). AM•EI has also been charged to provide faculty development to the SingHealth Residency Program. Since AM•EI’s inception in September 2012 through to June 2014, the Institute has enrolled over 1,500 interprofessional members.

Case study 23.4 Aligning academic promotion with medical school missions and faculty roles, Eastern Virginia Medical School, United States

The Eastern Virginia Medical School (EVMS) enrolled its first medical student class in 1973. EVMS aspires to be the most community-oriented medical school in the country, collaborating to meet the healthcare needs of the community by focusing on community and population health in its clinical, education and research activities. To accomplish this mission, the school aspires to attract and retain exceptional faculty who are outstanding in their professional goals and accomplishments, and who will thrive and find professional satisfaction in academic culture.

All faculty members are expected to demonstrate effective teaching, ongoing participation in scholarship and active engagement in service, with a level of expertise appropriate to their rank. As a community-based medical school, EVMS depends greatly on clinical faculty to teach and mentor medical students, residents and fellows, and improve the educational mission. Historically, EVMS’s promotion criteria emphasised research-based activities limiting the number of clinical ‘teaching’ faculty promotions. In 2012 EVMS revised its promotion criteria and created a single academic track, retaining the appropriate rigour and clarity associated with scholarly work, yet allowing faculty to create a realistic and attainable pathway for academic promotion in their area of strength.

All EVMS faculty (full-time salaried; full-time non-salaried; and community faculty) can demonstrate scholarship in any of the four faculty responsibility areas: clinical care, education, research/discovery and administration. Excellence in each area is evaluated using Glassick et al.’s (1997) criteria, elicited as part of the guidelines for each area. Thus far, 25 faculty members have gone through review for promotion under the new guidelines and reported that the concept of ‘fair’ expectations across all types of activities has struck a positive chord.

Resolving incongruities between teacher roles and organisational expectations and recognition

In order to be valued, educators must be able to document what they do and provide evidence of quality in a format that facilitates a consistent and efficient review by those charged with making recognition and reward decisions.

Clear goals

The Advocacy Workgroup at SingHealth and the EVMS promotion criteria provide explicit guidance to assure alignment of educator role expectations with promotion and career paths.

Appropriate methods

SingHealth utilised the international Academy of Medical Educators competencies to create a standardised template for an educator portfolio that allows faculty to document the work that they do within established domains of activity. AM.EI facilitates completion of a portfolio by collecting data for use by faculty in creating their portfolios. At EVMS, the promotion criteria are derived from the Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teachers seminal works on scholarship and the criteria for its assessment. Each adapted their criteria to align with organisation-specific missions and to support faculty roles with processes and resources.

Significant results

Each organisation has achieved early success in terms of numbers (e.g. AM.EI membership, attendance at events, number of faculty reviewed for EVMS promotion) and perceptions of fairness of expectations. Both have plans to continue to determine long-term impact in terms of catalysing quality improvement in educational activities, advancing educational scholarship and facilitating the recognition and promotion of educators.

Each organisation used workgroups to formulate their approach and included strategies to disseminate their plans and preliminary results. The ongoing communication of results will help to ensure that the resources, opportunities and criteria for success as educators are understood by all stakeholders: from individual faculty and their supervisors and mentors to the implementation agents and decision makers who have been tasked to carry out the work/apply the new criteria.

Reflective critique and summary

At the end of every journal article, authors typically review their findings, discuss the implications of their work within the larger context of related work and highlight next steps so that others may build on their work to advance the field. This reflective process allows us to improve continuously as individuals and collectively to enhance our work as a community of educators. Consistent with this process, we asked each of the case authors to reflect on how the initiative(s) described in their report contributes to valuing education in their organisation and to the institution’s culture. Their reflections and those of the chapter authors reveal recommendations that can serve as guideposts for individuals and organizations who want, in the words of Eastern Virginia case study authors, ‘education and teaching to be taken seriously . . . seen/accepted as an intellectual endeavour that is equally valued with research and that can provide recognition and rewards to its scholars’.

Create forums that bring teachers together

Efforts can start small within a department or on a larger scale, within a medical school, and then extend to the university, healthcare systems and/or nationally. As the case study authors from Aga Khan University reflected,

Through its multi-level courses, DED brings together teachers and educators at different levels of their careers fostering a community of educational leaders. It provides a platform for networking and sharing best practices from different institutions, different disciplines and different health professions across the country, thus facilitating and sustaining faculty engagement and collaboration for innovative teaching and learning.

Work simultaneously at the individual and organisational levels (e.g. university, healthcare system, accreditation bodies)

Case and chapter authors alike emphasise the importance of working to develop individuals as educators, be it through journal clubs, workshops and/or formal coursework leading to a degree. At the same time, assuring that the organisation and its infrastructure support educators requires the availability of educational expertise. Organisation of this expertise within a department or academy of medical educators facilitates the coordination of efforts to develop educators and enhance educational programmes. Last, but not least, promotion guidelines and awards/recognition processes must acknowledge the activities and impact of the work of educators. As the Singapore case study authors reflected, to achieve AM.EI’s goal of building a community of educators,

AM.EI and SingHealth established two strategic activities. First, we invited key education leaders to participate in a Fellowship Program in Medical Education . . . Second was the creation of a clinical educator track and guidelines for promotion along with the centralized documentation infrastructure to help program leaders be aware of the educational contributions of their faculty to facilitate the process of promotion.

Be visible

It is vital to communicate to all levels of the organisation continuously the importance of education and of the roles and activities of teachers. As indicated by the authors of the Singapore case study, ‘The mere presence of the AM.EI has raised interest and awareness of the importance of quality medical education activities and as faculty are trained . . . and being promoted, this culture will continue to grow.’

Plan for sustainability and growth through graduates

Individuals participating in the forums for educators gain expertise and they in turn must be engaged to teach/mentor the next generation of teachers. Over time, scholarly results are visible and have high impact. For example, the case study authors at AKU reported that their

programme alumni head departments of medical education in their own institutions, are spearheading innovations using educational experimentation grounded in research theory to bring about change and continuous quality improvement in Health Professions Education.

Recognise the time and effort required

Building and sustaining a community of educators takes time and sustained effort. As the Aga Khan case study authors commented, ‘it just doesn’t happen . . . it has taken a quarter century to get here’.

As health profession educators, we and our sponsoring organisations are entrusted to prepare the next generation of healthcare providers who will be responsible for delivering safe and effective care for patients and populations, at the lowest possible cost (Institute for Healthcare Improvement 2014). To fulfil this public trust, educators and organisational leaders must have the courage and commitment, as evidenced in our case studies, to develop, recognise and reward our teachers and educational scholars continuously; to create forums that bring teachers together, make these efforts visible, work simultaneously at the individual and organisational levels to advance education and educators, all the while recognising that change takes time but does yield results in terms of improving our educational programmes to meet healthcare needs.

As educators we are not alone. Common language and frameworks are emerging to help us communicate and share best practices, strategies and outcomes for developing and rewarding teaching expertise and educational scholarship. The Carnegie Foundation’s work on scholarship has emerged globally as a cross-cutting, systematic, criteria-based framework informing the work and case studies presented in this chapter. Application of this framework also assures that our efforts to develop, assess and value medical teachers and their work as educator scholars is rigorous, equitable and transparent. Using the scholar criteria to guide and evaluate our work will enable us to improve health profession education continuously and fulfil our entrusted roles.

• A rigorous, equitable and transparent criteria-based framework is now available to develop, assess and value medical teachers and their work as educators.

• Educators should create and sustain visible forums to bring teachers together to share evidence-based best practices to facilitate and sustain innovative teaching and learning.

• Educational leaders must partner with organisational leaders to ensure that the organisation and its infrastructure support educators, including revising academic promotion and award processes.

Bibliography

Boyer, E.L. (1990) Scholarship reconsidered. Priorities of the professoriate. Lawrence, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Glassick, C.E., Huber, M.R. and Maeroff, G.I. (1997) Scholarship assessed: Evaluation of the professoriate. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Grammaticos, P.C. and Diamantis, A. (2008) ‘Useful known and unknown views of the father of modern medicine, Hippocrates and his teacher Democritus’, Hellenic Journal of Nuclear Medicine, 11(1): 2–4.

Gusic, M.E., Amiel, J., Baldwin, C., Chandran, L., Fincher, R., Mavis, B., O’Sullivan, P., Padmore, J., Rose, S., Simpson, D., Strobel, H., Timm, C. and Viggiano, T. (2013) Using the AAMC toolbox for evaluating educators: You be the judge!, MedEdPORTAL. Online. Available HTTP: www.mededportal.org/publication/9313 (accessed 6 August 2014)

Gusic, M.E., Baldwin, C.D., Chandran, L., Rose, S., Simpson, D., Strobel, H.W., Timm, C. and Fincher, R.M. (2014) ‘Evaluating educators using a novel toolbox: Applying rigorous criteria flexibly across institutions’, Academic Medicine, 89(7): 1006–11.

Hutchings, P. and Shulman, L.S. (1999) ‘The scholarship of teaching: New elaborations, new developments’, Change, 31(5): 10–15.

Institute for Healthcare Improvement (2014) The IHI triple aim. Online. Available HTTP: www.ihi.org/Engage/Initiatives/TripleAim/Pages/default.aspx (accessed 30 June 2014).

Irby, D.I. (1994) ‘What clinical teachers in medicine need to know’, Academic Medicine, 69(5): 333–42.

Kirkpatrick, D.L. and Kirkpatrick, J.D. (2006) Evaluating training programs: The four levels (3rd edn), San Francisco, CA: Berrett-Koehler Publishers.

Krishnan, R. and Ng, I. (2012) ‘Academic medicine: Vision to reality’, Annals Academy of Medicine, 42(1): 2–4.

Simpson, D., Fincher, R.M., Hafler, J.P., Irby, D.M., Richards, F.B., Rosenfeld, G.C. and Viggiano, T.R. (2007) ‘Advancing educators and education by defining the components and evidence associated with educational scholarship’, Medical Education, 41(10): 1002–9.