6: Urban Pathology and The Limits of Social Research

W. E. B. Du Bois’s The Philadelphia Negro

Every one knows that in a city like Philadelphia a Negro does not have the same chance to exercise his ability or secure work according to his talents as a white man.

“Of greatest importance,” wrote W. E. B. Du Bois of his two years of graduate study at the University of Berlin, “was the opportunity which my Wanderjahre in Europe gave of looking at the world as a man and not simply from a narrow racial and provincial outlook.” His participation in middle-class German youth’s postcollegiate interlude of travel had followed undergraduate work at Fisk University in Tennessee, where he spent summers teaching the children of black farm workers in rural schools, and graduate study at Harvard. Du Bois’s wide-ranging experience surely fed his romantic, mystical temperament, which may have compensated for his humble beginnings in Great Barrington, Massachusetts, as the only child of a single mother (his father deserted the family during Du Bois’s infancy). But an international outlook ultimately led Du Bois back to race ideals. As part of a ritualistic, solitary celebration of his twenty-fifth birthday in Germany, complete with candles and incense, he pledged to devote himself to racial uplift: “I [will] therefore . . . work for the rise of the Negro people, taking for granted that their best development means the best development of the world.” Du Bois’s retrospective description of his developing race consciousness, certainly the product of a uniquely privileged education, disclosed his firm belief, shared by many educated blacks, that the black intelligentsia held the key to race advancement.1

While in Germany he had awakened to the possibilities of applying to the study of America’s “Negro problem” the social science methods he had learned from the sociologist Max Weber, the economist Rudolf Virchow, and the nationalist historian Heinrich von Trietschke. Du Bois returned to America in 1894 and joined the faculty of Wilberforce University, the African Methodist Episcopal church school in Xenia, Ohio. He found the religious school unsympathetic to social research. Thus in 1896, he eagerly accepted a one year appointment at the University of Pennsylvania to conduct a study of Philadelphia’s black community. Influenced, like the many educated blacks of his era, by the boundless idealism of uplift ideology, Du Bois had hoped to provide as much of a solution to the Negro problem as could be accomplished by a single book.

Du Bois’s landmark social study The Philadelphia Negro (1899) was the product of his stay in “the worst part of the Seventh Ward . . . where kids played intriguing games like ”cops and lady bums’; and where in the night when pistols popped, you didn’t get up lest you find you couldn’t.” Having moved there just after his marriage to Nina Gomer, Du Bois had undertaken, with the help of an assistant, Isabel Eaton, a thorough canvass of the homes of the Seventh Ward, where he claimed to have personally “visited and talked with 5,000 persons.” Much later, in his autobiography, Du Bois recalled that the study’s sponsors at the university had sought scientific validation of the view that “the corrupt, semi-criminal vote of the Negro Seventh Ward” should be the target of the latest of the city’s “periodic spasms of reform.” Instead, his study hoped to reveal “the Negro group as a symptom, not a cause; as a striving, palpitating group, and not an inert, sick body of crime.” Du Bois was only partially successful in this endeavor.2

In 1896, however, Du Bois probably had little idea of the intentions of the study’s sponsors. He regarded social research as the basis for “A Program of Social Reform,” which was the subject of a lecture he gave in 1897 while conducting his research. Sharing the progressives’ confidence in the reformist potential of applied intelligence and expertise, Du Bois sought to promote a more enlightened approach to issues like crime, linking it to poverty and a low standard of social justice, within which “selfishness and greed prevail[ed].” Writing in the Independent, Du Bois took pains to dissociate his approach from stereotypes and argued that “the first and greatest cause” of Negro crime in the South “is the convict lease system,” suggesting that strict criminal codes and overzealous enforcement inflated statistics of black crime.3 As for the causes of urban crime (“misfortune, disease, carelessness, selfishness or vice”), Du Bois maintained that “ignorance of the cause is the greatest cause.” A reform program that sought “individual regeneration aided by ability and knowledge” was “social opportunism which strives toward social science as its goal.” Fusing missionary ideals of social service and education with a boundless faith in reason and positivism, the work was not only important for the development of empirical sociology in America, but it also brought a rare sophistication of social and historical analysis to racial uplift ideology.

More typical was its earnest attempt to demonstrate the social stratification and complexity of the black community, and the indispensable leadership role of its “better class.” The tenor of Du Bois’s thinking at the time, pursuing an ethical vision of social organization in vaguely religious terms reminiscent of the abolitionist reform spirit, led him to propose “the raising of the present popular ideal from mere money-getting to that of common property—common weal.” Such romantic antimaterialism would soon find its way into The Souls of Black Folk. Indeed, as Arnold Rampersad has observed, it was while researching The Philadelphia Negro that Du Bois had first published that work’s central idea of “double consciousness,” with its warring Negro and American ideals and the spiritual strivings of elite blacks to forge a de-essentialized identity that transcended white prejudice.4

William Ferris, Anna Cooper, and Du Bois illustrate the complex struggles over black consciousness, both individual and collective, within racial uplift ideology. This struggle against and within a manichean binary logic of race, reflecting an ever-changing sociohistorical context, underscored the untenable nature of its avowed pursuit of a unified black middle-class subject predicated on historically static, and implicitly racialized, ideals of bourgeois morality. Black identity, and the politics that issued from it, remained highly situational, despite black elites’ attempts to ground uplift ideology in what they considered to be the eternal verities. From this perspective, Du Bois becomes much more than the militant antagonist of conservative black leadership led by Booker T. Washington. Over the course of his long life, Du Bois embraced a wide range of positions that departed from his image as an egalitarian champion of civil rights. Readers of David Lewis’s magisterial biography realize that Du Bois congratulated Washington after his Atlanta Exposition speech in 1895 and was in turn offered a teaching job at Tuskegee by the Wizard shortly after he had accepted the position at Wilberforce. As a delegate at a meeting of the Afro-American Council, Du Bois sided with Washington against a militant faction, telling reporters that the organization would be “very sorry if it went out into the world that this convention had said anything detrimental to one of the greatest men of our race.”5 Du Bois’s Book-erite period ended with The Souls of Black Folk, which the Southern Workman dismissed as “unhealthful,” claiming that “conditions in the South are not so bad as they are pictured here” by one whose northern background and elite education disqualified him as an authentic spokesman on race relations in the South.6 Indeed, Du Bois’s Philadelphia study may have been crucial in the intellectual transformation culminating in his public criticism of Washington’s leadership. Later, during World War I, and a period of racial polarization which saw the segregation of federal employment facilities instituted under Woodrow Wilson’s administration, Du Bois raised eyebrows and ire among black militants with an editorial in the Crisis asking African Americans to “forget our special grievances and close our ranks shoulder to shoulder” with white citizens and the allied nations “fighting for democracy.” Mark Ellis has documented the link between the prowar editorial and Du Bois’s behind-the-scenes campaign for an officer’s commission from the War Department. Hubert Harrison, the West Indian socialist and black nationalist, had suspected as much. Although remembered as an integrationist for his work with the NAACP, Du Bois was ousted from the organization in 1934 by Walter White for his view that segregation held potential economic and political benefits for African Americans. In his last years, when he joined the Communist Party, Du Bois was an unrepentant Stalinist, goaded by the virulent racism of the Cold War era’s unholy alliance between liberal and segregationist democrats and the harassment he suffered at the hands of the State Department, which arrested him in 1951 for his anticolonial and pacifist activities. Although acquitted, he was abandoned by the civil rights establishment and its leadership. Past ninety, Du Bois exiled himself to Ghana, where he died in 1963, on the day before the March on Washington.

Du Bois wrote a final autobiography in Ghana, subtitled “A Soliloquy on Viewing My Life from the Last Decade of Its First Century.” In this work, the Marxist Du Bois subjects the political ideals of his youth to a withering auto-critique. He had truly been a benighted product of the nineteenth century. Recalling the establishment of the Congo Free State by Belgium, and the contemporary view that the Berlin conference of 1885 would benefit an African continent racked by the slave trade and liquor, Du Bois recalled, “I did not question the interpretation which pictured this as the advance of civilization and the benevolent tutelage of barbarians.” Like many others, he considered strikes “ignorant lawlessness,” and only with hindsight was “rich and reactionary” Harvard revealed to him as “the defender of wealth and capital, already half ashamed” of the radical abolitionists Charles Sumner and Wendell Phillips.7

Du Bois’s utterances from the 1890s show that he espoused uplift ideology in its more conservative aspects, much of which echoed the values of the ruling Anglo-American bourgeoisie. As a youthful scholar seeking admittance into the black intelligentsia, his outlook shared a great deal with that of his more established elders. Addressing the American Negro Academy, which was founded in 1897 to foster academic research into race questions, Du Bois warned that the organization “ought to sound a note of warning that would echo in every Black cabin in the land: Unless we conquer our present vices they will conquer us; we are diseased, we are developing criminal tendencies, and an alarmingly large percentage of our men and women are sexually impure.”8 This is not the militant Du Bois we are accustomed to. Years later, Du Bois summed up the limitations of his utilitarian, scientific approach to reform and uplift: “I did not have any clear conception or grasp of that colonial imperialism which was beginning to grip the world.”9 His confidence in social science research as an antiracist panacea would help him negotiate his anxieties surrounding urbanization among African Americans. The background to The Philadelphia Negro is Du Bois’s incipient consciousness of a global imperialism that, combined with the progressive disfranchisement and segregation of African Americans, would reveal the fault lines and parochialisms of moralistic, self-help uplift ideology, and its intimations of urban pathology.

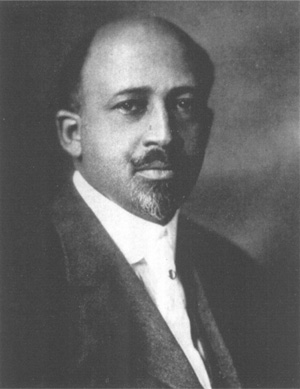

William Edward Burghart Du Bois, ca. 1910.

The very moment of the production of The Philadelphia Negro is thus fraught with ideological tension. Often asserting uplift’s doctrine of class stratification and, therefore, the duty of privileged blacks to set a high moral tone for the black masses, Du Bois’s analysis of discriminatory wages, rents, and living conditions for blacks in Philadelphia nevertheless rendered the usual exhortations of self-help, individualism, and the moral pieties of uplift quixotic at best. Just as uplift’s function for black elites was in part to impose a sense of control and order on the overwhelming problems facing blacks in cities and elsewhere, Du Bois’s study aspired to similar ideals of organized intelligence. He set out “to lay before the public such a body of information as may be a safe guide for all the efforts toward the solution of the many Negro problems of a great American city.” Yet the overwhelming pattern unearthed by his reformist empiricism was a degree of white prejudice and systemic exclusion impervious to his ideals of enlightened reason.10

While brilliantly advancing sociological research methods, Du Bois’s study also exhibited the moral and religious animus underlying much early social science writing. The Philadelphia Negro broke tentatively with the usual perception of the cultural and moral shortcomings of urban blacks and rejected prevailing hereditary explanations of poverty and crime. But at the same time, Du Bois’s construction of class differences among blacks was predicated on cultural and moral distinctions measured by the degree of conformity to patriarchal family norms. This dominant perspective behind Du Bois’s reading of urban poverty anticipated the work of subsequent studies, most notably those of E. Franklin Frazier, which characterized black poverty as an irregular preponderance of matriarchal authority. Frazier’s work, like Du Bois’s, had intended to demonstrate the harmful effects caused by discrimination. Frazier’s theme of family disorganization had its greatest impact with the Moynihan report, published in 1965, which gave new impetus to the myth of black matriarchy, and reentered mainstream media discourse on race as the “culture of poverty” thesis advanced by a legion of informal social commentators, journalists, and policymakers. The contentious discussions of race, social class, gender, and urban poverty since the Moynihan report have their origins in the contradictions of Du Bois’s study, which represented blacks as both discriminated against and morally suspect, subject to inegalitarian constructions of deviance.

In its day, Du Bois’s study was seen as fair-minded and objective, insofar as it seemed to confirm its reviewers’ preconceptions about race. Hampton Institute’s Southern Workman welcomed the author’s unwillingness “to with-hold ugly facts, such as those relating to crime and pauperism and low standards in family life.” While the Nation acknowledged that color prejudice “is a far more powerful force than is commonly believed,” it strangely concluded that “the lesson taught by this investigation is one of patience and sympathy towards the South, whose difficulties have been far greater than those of the North.”11

Elite blacks may have found poor blacks in urban slums embarrassing incarnations of minstrel stereotypes. Or, they might have been sincerely moved by their plight and committed to settlement work. But often, formulaic representations of urban pathology were crucial to their self-image of racial respectability. As African Americans left the South for cities and towns in the region, and later, for the urban North, to compete for industrial and domestic jobs in a labor market as restricted as the one they left behind, social and demographic change challenged black elites to reconsider their relationship to “the race.” Several ideological currents merged to produce the image of urban pathology: the view of race progress as epitomized by home life and patriarchal authority, combined with the cultural inertia of the plantation legend, which claimed that African Americans were morally better off in the rural South close to the soil; the negrophobic commentaries of social science writers who perceived the race as diseased, criminal, and immoral; longstanding popular traditions of minstrelsy that mocked the urban black male as a buffoon or branded him as a sexual menace; white prejudices against urban blacks as economic competitors with white workers for industrial jobs; the corollary expectation that African American labor remain tied to agricultural cotton production; and the preponderance of single, independent women in cities. African American elites who invoked images of urban pathology did not necessarily endorse this entire battery of assumptions. Accusations of urban pathology implied a normative view of social order and labor organization that perhaps carried moral authority in the minds of black elites. Nevertheless, to speak of urban blacks as immoral or beset by family disorganization was in Du Bois’s day to risk unleashing an avalanche of racist metaphors. Ultimately, however, uplift’s moral assumptions of urban pathology reflected a developmental construction of race and class that bestowed on “better class” blacks an illusory sense of self-importance as it divested poor urban blacks of agency and humanity.

Prejudices against blacks on urban terrain were longstanding in the U.S. political culture. Carried over from minstrelsy’s image of the dangerous urban black dandy, these prejudices found respectable expression in social studies which purported to document black disease and mortality, as well as the race’s alleged predisposition to crime, vice, and immorality. Late-Victorian progressive reformers associated city life with dubious leisure activities such as visiting saloons (which, in Philadelphia, were also headquarters for black political organizations and patronage) and dance halls, along with prostitution and gambling. As these illicit pleasures and pastimes were increasingly confined to black neighborhoods, urban immorality was frequently imbued with a racial stigma. Moral reformers focused their efforts on black sections as those most contagious portions of the social organism.12

Black writers opposed the most unscrupulous attempts at empirical demonstration of racially defined pathology in cities. An example was Race Traits and Tendencies of the American Negro (1896), by Frederick L. Hoffman, an insurance company statistician. Hoffman predicted that diseases resulting from the immoral nature “of the vast majority of the colored population” would eventually lead to the race’s extinction.13 Such prejudices found support in theological circles as well, such as in Rev. C. G. H. Hasskarl’s book The Missing Link: Has the Negro a Soul? (1898). To Hasskarl, blacks were beasts bereft of a soul and the finer human attributes. Interestingly, as if to divert attention from assertions of urban pathology, Du Bois devoted part of The Souls of Black Folk to the virtuous black peasants he taught in rural Tennessee. In Philadelphia, however, Du Bois pursued a vision of scientific truth that might undermine racist representations, and that by focusing on changing social conditions, might disarm the race’s enemies, intellectual and otherwise.14

Du Bois’s historical analysis of blacks in Philadelphia reflected what many blacks, and for that matter, many others, were experiencing at the turn of the century—the class and cultural conflicts that the era’s general bromides of progress attempted to contain. Du Bois chronicled the black community’s struggles to first secure, and then maintain, whatever material and political gains it had achieved. He regarded the waves of European immigration, and the competition that ensued, disastrous for continued black advancement. Since their introduction to Philadelphia as slaves by the Dutch colonists during the seventeenth century (along with white indentured servants), “the Philadelphia Negro has, with a fair measure of success, begun an interesting social development,” only to be checked, as “twice through the migration of barbarians a dark age has settled on his age of revival.” Du Bois’s reference to immigrants as “barbarians” sounded a well-worn theme of black writers who associated racism at its most brutal, usually in the South, with a backward, barbaric feudalism identified solely with poor whites or immigrants. He recounted the violent mob disturbances and the economic competition that characterized blacks’ relations with immigrant groups in that city in the mid-nineteenth century. Identifying immigrants with social disorder, Du Bois, like many blacks, resented the presumption of white superiority so quickly learned by so many foreigners. Du Bois’s thinly veiled nativism, fueled by white racism, sought interracial cooperation with white Protestant elites. This did not change the fact, however, that immigrants were not the sole purveyors of race hatred. Still, Du Bois’s unvarnished portrayal of the retrograde trajectory of blacks’ changing status challenged uplift’s teleological assumptions of evolutionary progress.

Du Bois rooted the “Negro problem” in Philadelphia in a history of oppressive state actions. By 1750, the black population there had reached eleven thousand, and ordinances seeking to control and police the slave population were enacted throughout the eighteenth century. An act of 1726 sought to appease angry mobs of free white laborers by banning the hiring out of black slave laborers and mechanics. The act (suggesting an earlier version of urban pathology) declared that “it too often happens that Negroes commit felonies and other heinous crimes,” and it sought to restrict the emancipation of blacks, fearing an increase of pauperism. The basis for such legislation was the claim that equal rights for blacks would be injurious to social order. City ordinances of 1738 and 1741 considered the black population innately “disorderly.” Despite these restrictions, the antislavery agitation of the Quakers and the “broader and kindlier feeling toward the Negroes” brought by the war for independence aided the passage of the Act for the Gradual Abolition of Slavery in 1780. For Du Bois, a historical, environmental perspective, viewing changing race relations through the prism of the American Revolution, might refute the plantation legend.

Du Bois regarded the antebellum years following gradual emancipation as a time of advancement for blacks, followed by an initial period of “widespread poverty and idleness.” Lack of opportunities propelled “a rush to the city,” where “a secure economic foothold” was achieved through domestic service, and skilled and unskilled labor: “The group being thus secure in its daily bread needed only leadership to make some advance in general culture and social effectiveness.” Du Bois praised Absalom Jones and Richard Allen, former slaves who had purchased their freedom, for their role in founding the Free African Society in 1787, after white Methodists excluded black congregants. Besides offering a space for worship, the Free African Society provided for the relief of the sick, widows, and orphans, and provided burial expenses for its members. Allen, a blacksmith, went on to found the African Methodist Episcopal church, serving as the first bishop of “the vastest and most remarkable product of American Negro civilization.”15

Besides Allen and Jones, Du Bois mentioned James Forten, the Quaker-educated black businessman, as exemplary of the antebellum era’s brief heyday of self-help and institution building. Forten, Jones, and Allen helped muster black troops during the War of 1812. By 1820, Du Bois noted, the industrial revolution, economic stress after the war with Britain, the rapid influx of foreign immigration, the increase of free blacks and fugitive slaves, and the rise of the abolitionists all strained social tensions, “prov[ing] disastrous to the Philadelphia Negro.” Economic dislocations, combined with antislavery agitation, led to a renewed effort to displace black workers—“an effort which had the aroused prejudice of many of the better classes.” In sketching a vision of the past that was to serve as a metaphor for the present, Du Bois stressed the complicity of white elites in their failure to exercise leadership and restore order: “So intense was the race antipathy among the lower classes, and so much countenance did it receive from the middle and upper class, that there began a series of riots . . . against Negroes, which recurred frequently until about 1840, and did not wholly cease until after the war.” Du Bois devoted the next few pages to accounts of mob terror and rioting by the surplus population of rootless urban white males during the era of Jacksonian democracy. By 1837, the city constitution had deprived black men of their voting rights, which they had previously enjoyed for fifty years. Du Bois’s description of antebellum riots, the racism of immigrant groups, including many Americans recently arrived from the South, and of disfranchisement in the North mirrored contemporary threats to blacks.16

Du Bois confronted the perception among erstwhile white allies that urban black communities represented the antithesis of progress. Noting that “the development of the Philadelphia Negro since the [Civil] war [has] on the whole disappointed his well wishers,” he argued that immigration and “the development of large industry and increase of wealth” intensified competition for jobs, as “the little shop, the small trader [and] the home industry have given way to the department store, the organized company and the factory.”17 Du Bois lamented that racial exclusion accompanied industrialization. He observed ambitious blacks trying to better their condition, but found their opportunities for work “not only restricted by their own lack of training but also by discrimination against them on account of their race. . . . [T]heir economic rise is not only hindered by their present poverty, but also by a widespread inclination to shut against them many doors of advancement open to the talented and efficient of other races.” Thus, assumptions of free will and an equally free market characterized by “untrammeled competition” were inaccurate: “One never knows when one sees a social outcast how far this failure to survive is due to the deficiencies of the individual, and how far to the accidents of his environment. This is especially the case with the Negro.”18

In addition to demonstrating economic racism, Du Bois insisted on an environmental perspective, seeking “the tangible evidence of a social atmosphere surrounding Negroes, which differs from that surrounding most whites; of a different mental attitude, moral standard and economic judgment shown toward most other folk.” He believed such social bias could “plainly be seen” but sought to determine through “careful study and measurement . . . just how far it goes and how large a factor it is in the Negro problems.” He seemed to assume that instrumental rationality might cut race prejudice down to size.19

Du Bois was well aware of the pervasiveness of race prejudice. In a footnote, he rejected the usual practice of lowercase textual references to “the negro,” insisting that a group of nine million deserved a capital letter. His emphasis on the role of black leadership as teachers and moral guides to the black masses, and agents of uplift, anticipated his Talented Tenth theory of black leadership, a secularized missionary ethos in which he argued that only educated “exceptional men” could “save” blacks. But within the pages of The Philadelphia Negro, Du Bois struggled to reconcile self-help strategies of social control with racial polarization. In the antebellum period, self-help meant emancipation, but with the dawn of monopoly capitalism, business elites and philanthropists exercised a considerable voice in dictating the political and economic conditions of “self-help.” The tradition of self-help, Du Bois realized, was hard-pressed to withstand the struggle black entrepreneurs and service workers waged to survive competition with big business and hostile white workers.

Behind Du Bois’s exhortations to self-reliance loomed the problem of powerlessness and the obstacles to the accumulation of wealth among blacks. Indeed, blacks’ economic gains and resources, never large to begin with, were eroding. Black dominance of the catering business was on the wane, yielding to the preference of its upper-class clientele for white competitors. And even if color barriers were not insurmountable, the concentration of corporate power diminished opportunities. Small businesses run by blacks were being squeezed by the “development from the small to the large industry, from the house-industry to the concentrated industry, from the private room to the palatial hotel.” Du Bois grimly noted the exclusion of black men from trades and organized labor, and the competition from German and Italian immigrants that reduced the number of barbering and personal service jobs for black men. In many cases, white competitors displaced longstanding relationships with white employers “and a larger place for color prejudice was made.” Prejudice had become more than a fact of life for black Philadelphians, as black-owned cemetery companies had evolved out of “the curious prejudice of the whites against allowing Negroes to be buried near their dead.”20

Du Bois’s claims of class differentiation among blacks, delineating a complex taxonomy of groups within the group, were none-too-subtle prods aimed at the slumbering moral sense of many white elites. Noting that “every group has its upper class,” he observed that “as it is true that a nation must to some extent be measured by its slums, it is also true that it can only be understood and finally judged by its upper class.” Du Bois argued that “nothing more exasperates the better class of Negroes . . . than this tendency to utterly ignore their existence.” Attributing the chronic invisibility of the black intelligentsia to “so much misunderstanding or rather forgetfulness and carelessness,” Du Bois insisted that the “aristocracy of the Negroes” formed the “realized ideal of the group.” He demanded that black Americans be judged by exemplary, accomplished individuals. “In many respects it is right and proper to judge a people by its best classes rather than by its worst classes or middle ranks. The highest class in any group represents its possibilities rather than its exceptions, as is so often assumed in regard to the Negro.”21

Du Bois further challenged the homogenizing slanders of racism by documenting the uneven social development within the black community in the incidence of illiteracy and mortality, which he attributed to socioeconomic and geographical factors, not racial traits. He found a general decline in illiteracy among blacks, led by the achievements of the postbellum generation of black Philadelphians. Comparing the illiteracy rates of blacks to those of foreign immigrant populations in Philadelphia, Du Bois and Eaton found that blacks had a lower rate of illiteracy, at 18.56 percent, than the Irish (25.79 percent), Hungarians (30.84 percent), Poles (40.27 percent), Russians (41.92 percent), and Italians (63.63 percent). Only German immigrants (14.74 Percent) scored better than blacks. This sort of comparative argument, marshalled for antiracist purposes, would be taken up by other students of race and urban poverty, including Du Bois’s future ally in the NAACP, Mary White Ovington. The socialist reformer conducted social research on blacks in New York City. Much later, such comparative arguments, marshaled within liberal sociological discourse on race and ethnicity at the height of the civil rights movement, might serve the dubious end of contrasting a maladaptive black “culture of poverty” unfavorably with the perceived cultural adaptation and social mobility enjoyed by previously marginalized ethnic groups.22

On the subject of mortality, Du Bois sought to discredit the “disposition among many to conclude that [black mortality] is abnormal and unprecedented, and that, since the race is doomed to early extinction, there is little left to do but to moralize on inferior species.” He rejected claims of black mortality, citing, for one thing, the unreliability of previous statistical records. He speculated that black mortality was insignificant compared to what “must have been an immense death rate among slaves, notwithstanding all reports as to endurance, physical strength and phenomenal longevity.” Du Bois suggested the extent to which claims of black mortality fed nostalgic plantation myths of coddled, contented slaves. He detected a decline in black mortality, from an annual average of 47.6 deaths per 1,000 from 1820 to 1830 to 28.02 from 1891 to 1896, a figure that included stillbirths. Again, he found comparison with European nations instructive: “Compared with modern nations the death rate of Philadelphia Negroes is high, but not extraordinarily so.” Hungary, Austria, and Italy were found to have comparable figures. Although black mortality surpassed that of whites, mainly in cases of such pulmonary diseases as tuberculosis and pneumonia, Du Bois saw this as a function of substandard, unsanitary living conditions, “partly by their own fault, partly on account of the difficulty of securing decent homes by reason of race prejudice.” He also cited poverty and its attendant evils—insufficient clothing, poor diet, and inadequate access to medical care as factors. “There are still many of the old class of root doctors and patent medicine quacks with a lucrative trade among Negroes,” Du Bois lamented (the Frederick Douglass Memorial Hospital and Nurse Training School, which served blacks, was founded by Dr. Nathan Mossell in 1895).23 In addition, Du Bois brought a historical perspective to his analysis of mortality. Regarding “consumption [tuberculosis] it must be remembered that Negroes are not the first people who have been claimed as its peculiar victims; the Irish were once thought to be doomed by that disease—but that was when Irishmen were unpopular.” He concluded that mortality “should . . . act as a spur for increased effort and sound upbuilding, and not as an excuse for passive indifference, or increased discrimination.”24

By calling attention to social change and statistical variations within a socially stratified black community, Du Bois effectively countered homogenizing racist assumptions. Still, this strategy was fraught with difficulties. When his scheme of social classification strayed from quantitative methods, venturing into the more nebulous realm of observation of the sexual morality and behavior of blacks, Du Bois risked echoing caricatures of immoral and disorderly black masses. “Among the lowest class of recent immigrants and other unfortunates,” Du Bois observed, “there is much sexual promiscuity and the absence of a real home life.” While he cautioned that “of the great mass of Negroes this class forms a very small percentage and is absolutely without social standing,” his view that “they are the dregs which indicate the former history and the dangerous tendencies of the masses” suggested that respectable blacks claimed their status and humanity somewhat parasitically. This may have earned Du Bois a measure of moral authority to some readers, but to less friendly others, such statements might confirm what they already “knew” about blacks, in Philadelphia and elsewhere.25

Du Bois’s description of the Seventh Ward, represented in the form of a walking tour, read like a descent into an urban heart of darkness, striking a tone that shed doubt on his scholarly detachment: “The corners, night and day, are filled with Negro loafers—able-bodied young women and men, all cheerful, some with good-natured, open faces, some with traces of crime and excess, a few pinched with poverty. They are mostly gamblers, thieves and prostitutes, and few have fixed and steady occupation of any kind.” To observe and “know” was inescapably to judge and condemn. Even worse, Du Bois’s attempt to measure blacks’ respectability was complicated by “a curious mingling of respectable working people and some of a better class, with recent immigrations of the semi-criminal class from the slums.”26

Du Bois’s highly distanced and subjective figurations of the poor reflected his personal social anxieties and rhetorically advanced his claims for class differentiation.27 But such bourgeois-tinged rhetoric risked undermining his findings attributing blacks’ condition to a discriminatory social environment. Du Bois’s analysis of the percentage of blacks who worked for a living, for example, was clearly intended to disprove stereotypes of black idleness and criminality. But such an analysis invariably leaves the reader where he started; the impressionistic character of many of Du Bois’s observations—of “able-bodied loafers,” faces with “traces of crime and excess” and the notion of “respectability”—reveal the extent to which the sociologist’s questions, let alone the conclusions, are dictated by images of urban pathology.28 Du Bois’s descriptions of the impoverished residents of the Seventh Ward show little of the moral resiliency and heroism with which he endowed the peasant families of rural Tennessee in The Souls of Black Folk.29 Lacking redemptive ties to the soil and farming, the abject urban dwellers Du Bois depicted seemed even more dependent on the saving presence of a black elite.30

Du Bois’s (and racial uplift ideology’s) argument of class stratification as a sign of progress was riddled with contradictions. Social distance between elites and masses was reconciled by uplift’s contested ethic of responsibility. Indeed, Du Bois rather dubiously believed that this “better class” of blacks was ignored by whites because black elites failed to cultivate “strong ties of mutual interest” with the black masses. He noted the lack of a proper spirit of noblesse oblige: “[Elite blacks] are not the leaders or ideal makers of their own group in thought, work, or morals. They teach the masses to a very small extent,” and generally lack contact with them. This “anomalous position” of elite blacks in the North must have clashed with a view of uplift partly modeled after the progressive moral reform crusades of the day, but also informed by a not so distant antebellum tradition of service and self-help within the black community of teaching, cooperation, and resource sharing, intellectual and material. Although he argued that whites recognize class differences among blacks, he sensed that this recognition itself was inimical to the goals of uplift and racial solidarity: because “the first impulse of the best, the wisest and the richest is to segregate themselves from the mass,” there was “more . . . dislike and jealousy on the part of the masses than usual.” He argued that the “better classes” among blacks “have their chief excuse for being in the work they may do toward lifting the rabble.” In his study of Du Bois’s social thought, Joseph DeMarco called the work’s rhetoric of social classification “a condescending provision of social responsibility” and noted that the necessary schism had become even more rigid in a 1901 essay, “The Black North”: “A rising race must be aristocratic; the good cannot consort with the bad—not even the best with the less good.” Such statements revealed more about the anxieties of Du Bois’s elite perspective than about the social condition of the masses.31

The problem was that this sort of separate-but-equal claim for cultural authority simply didn’t deliver the status and influence it promised black elites, to say nothing of what little it had to offer less privileged blacks. How could a bourgeois ideology that was itself steeped in racial categories slay the hydra of racism? The biggest obstacle to this ideology of mutual solidarity and altruistic service was the vicious circle of institutionalized racism and white prejudice: “This feeling [of repulsion] is intensified by the blindness of those outsiders who persist even now in confounding the good and bad, the risen and fallen, in one mass.” Although Du Bois realized that “the uncertain economic status” of relatively privileged blacks made it difficult for them “to spare much time and energy in social reform,” the fact remained that these blacks were as vulnerable to being regarded as social outcasts as those unassimilated, immoral blacks upon whom they sought to prop up their own status within the social hierarchy. Uplift was an ideological response by blacks to a segregated, deeply racist society that prescribed their subordinate place and thus circumscribed their opportunities. In effect, when Du Bois employed uplift ideology to mobilize the missionary zeal of “better class” blacks, hoping to gain the respect and recognition of influential, progressive whites, he was exhibiting a variant of double-consciousness.32 It is important to recognize both the difficulties Du Bois contended with and his uneasy relationship to the community he studied.33

Bourgeois sexual morality provided Du Bois with a crucial means of articulating class differences among blacks, facilitating in his study a problematic linkage of poverty and immorality, and equating the disturbing presence of unmarried black women with promiscuity. He associated unemployment with idleness and sin, but his vision of lower-class status especially faulted all signs of the absence of the patriarchal black family. The problem was that many blacks suffered from “the lack of respect for the marriage bond,” from which “sexual looseness . . . adultery and prostitution” soon followed. Consequently, Du Bois often described the struggles and low status of urban blacks in terms of improper sexual behavior and viewed everything short of “the monogamic ideal” as a lapse in female chastity, sometimes viewed in isolation from any male complicity. Although he called for compassion in undertaking social research as a guide to reform,34 his approach was not always conducive to empathy with the subjects of his study.35

Du Bois’s discussion of the weakness of the family stemmed from the uplift assumption of the home and family as signs of progress and security, and sources of strength. Indeed, much commentary on urban poverty targeted the status of the family as the barometer of social health or pathology. To many blacks, home life represented a realm of security, stability, and success, however modest, and it affirmed respectable manhood and womanhood. For many, the patriarchal family meant freedom from the domination that had kept black men and women divided, demoralized, and homeless.

It is likely that the difficulties he faced as a black man struggling to make a decent home for his new bride in the midst of the Seventh Ward’s slums contributed to his judgmental stance. An uneasy realization of his own tenuous place within a social equation arrayed against him and untold others doubtless required a strenuous effort to maintain at the very least, a psychic distance from his objects of inquiry and their plight. Racial and social oppression stunted the lives and aspirations of many educated and elite blacks, but the masses’ poverty was nobody’s fault but theirs, by virtue of their moral shortcomings. This same logic applied to gendered representations of black oppression. As black progress had traditionally been defined in male-centered ways, Du Bois defined racial oppression as a process of emasculation. He noted the devastating blow to male self-respect dealt by the social impediments to the protection and support of black women in bourgeois families and homes. But if black men could be so victimized, unprotected black women were cast as culpable outside the sanctions of marriage and the patriarchal family. Du Bois occasionally singled out poor black women as blameworthy for family instability. This ran counter to his environmental approach. Blacks faced a severely restricted labor market in low paying menial and domestic jobs, and their confinement and crowding within slum areas made them vulnerable to exorbitant rents. Such discrimination, in rendering the support of families difficult at best, faded from an analysis that often stressed debased morals.

The Philadelphia Negro illustrated the tension within uplift ideology that combined altruistic ideals of compassionate service with unforgiving condemnations of those who appeared not to heed uplift’s moral prescriptions. Du Bois was casting out society’s most visible outcasts even further from “respectable” society: “Let us glance at the general character of the ward. . . . we can at a glance view the worst Negro slums of the city. . . . here once was a depth of poverty and degradation almost unbelievable. Even today there are many evidences of degradation, although the signs of idleness, shiftlessness, dissolutenenss and crime are more conspicuous than those of poverty.”36

To his credit, such value judgments did not prevent Du Bois from an exhaustive investigation of urban conditions. He compiled detailed evidence of the economic discrimination that prevented blacks from meeting the cultural dictates of upright moral behavior—chastity and matrimony. He found employment opportunities for black Philadelphians in 1896 largely restricted to low-paying domestic and personal service jobs. Of employed blacks, 73 percent worked as servants; of this percentage, 61 percent were men and 88.5 percent women. Higher up the occupational ladder he found barely 2 percent of employed blacks were learned professionals, “represented among Negroes by clergymen, teachers, physicians, lawyers and dentists, in the order named.” Du Bois’s findings, particularly in comparison to the rest of the city, may have run counter to some expectations. Whatever signs of idleness and shiftlessness he reported, he found that 78 percent of blacks worked for a living, as against “55.1 per cent for the whole city, white and colored.” He took these figures as evidence of a lack of accumulated wealth among blacks “arising from poverty and low wages; the general causes of poverty are largely historical and well known.” Du Bois attributed low wages to the lack of job opportunities for blacks and “the competition that must ensue.” These impoverished conditions were disastrous to conventional moral standards. Black women’s “chances of marriage are decreased by the low wages of the men” and the “large excess” of black women in the city. For men, low wages meant the unpleasant choices of either “enforced celibacy” or “dissipated lives,” or “homes where the wife and mother must also be a bread winner.”37

To Du Bois, joblessness meant immorality, and the consequences of all this were clear on the “conjugal condition” of the residents of the Seventh Ward, as he focused on the “widespread and early breakup of family life.” Even those who tried to fulfill the dictates of the work ethic found it hard to stay afloat. Du Bois went on to describe the struggles of black servants to live respectable lives: “The economic difficulties arise continually among young waiters and servant girls,” who, lonely and isolated, “thoughtlessly marry and soon find that a husband’s income cannot alone support a family.” This led to “a struggle which generally results in the wife’s turning laundress, but often results in desertion or voluntary separation.” Noting that one-third of black Philadelphians were servants, Du Bois considered it a “maladjustment in social relations” that so many were forced to earn a living in domestic service, “adding a despised race to a despised calling.” Still, even as he argued that matters might be improved if whites regarded domestic service and their black employees more highly, he wrote poignantly of how the humiliations of domestic service clashed with the aspirations of even the ablest and most ambitious blacks, breeding in them sufficient resentment to affect the quality of their service: “All those young people who, by natural evolution in the case of the whites, would have stepped a grade higher” than their parents “in the social scale, have . . . been largely forced back into the great mass of the listless and incompetent to earn bread and butter by menial service.” Noting at the same time a trend toward the displacement of black servants by white immigrants, which exacerbated “crime, pauperism and idleness among Negroes,” Du Bois finally called for better training and urged employers to “recognize more keenly . . . the responsibility of the family toward its servants” in allowing them to live on the premises as members of the family. Even as he wrote with some empathy for the plight of servants, he tended to speak of them pa-ternalistically, as if they lacked virtuous self-reliance. Again, the problem became a matter of moral blight and disease centering on blacks: “Thousands of servants no longer lodge where they work but are free at night to wander at will, to consort with paramours, and thus to bring moral and physical disease to their place of work.” Such statements were unlikely to gain sympathy or job security for black domestic workers.38

Urban Pathology as Family Disorganization

The destruction or absence of the patriarchal family among blacks was symptomatic of exclusion from unions and industrial wage labor. Racist minstrel and journalistic discourses trumpeted images of absent patriarchy as evidence of black inferiority. As part of a patriarchal U.S. culture, African Americans understandably regarded conformity with patriarchal gender norms as the crucial standard of race progress. But black nationalist intellectuals, haunted by the memory of slavery and its destruction of the family, restricted their idea of the race’s oppression to the terms dictated by minstrelsy. To be the patriarch, the master of one’s family, was ardently desired by African American men, who considered this an essential prerequisite of respectability, civilization, and progress. This defensive preoccupation with the family, bourgeois morality, and individual behavior as preconditions for humanity was a distraction from the excesses of monopoly capitalism and its gross disparities in wealth and power.

Du Bois tried to place his discussion of the black family within a broader, environmental context. In explaining the weakness of the family, he sought a precarious balance of both discrimination and moral weakness: “The causes of desertion are partly laxity in morals and partly the difficulty of supporting a family.” The iron fist of his Darwinian Calvinism was cushioned somewhat by a velvet glove of compassion. Aware that opportunities for talent and ambition were “confined to the dining room, kitchen and street,” Du Bois nonetheless sometimes pointed an accusing finger at black women whose condition as “unmarried mothers . . . represent[s] the unchastity of a large number of women.” Social phenomena such as the excess numbers of “single females” in the city, but also their prevalence in exploitative domestic jobs, only served to provide Du Bois with further evidence of faulty morals. In Du Bois’s scheme, working black women embodied the weakness of the patriarchal family, a condition from which prostitution seemed only a short plunge. Patriarchal authority remained the crucial criterion of black bourgeois stability.39

Within racial uplift ideology, however, status classifications based on the wife’s presence in the home presented an unattainable standard for many black women and men. While Du Bois certainly dwelled on the moral failings of black men, referring often to gamblers, criminals, rogues, and rascals, women who failed to meet the lofty standard of motherhood appeared to bear the brunt of his findings on family instability. Ranked slightly above the unmarried in moral status were married women who worked outside the home—respectable, but less so. Black wives who were homemakers represented the highest status, signaling decent homes sustained by male support.40

Du Bois’s placement of poor urban blacks within a lower state of moral development by virtue of the relative absence of family stability was linked to the moral double-standard to which black women were particularly vulnerable. Black women often worked to support themselves, under circumstances, as during slavery, and later, in domestic jobs, that obliterated the boundary between public and private life that bourgeois selfhood required. In a footnote Du Bois gave a fairly concise view of racial oppression, construing female immorality as the outcome of black emasculation. The general lack of social protection for black women and girls not only left them vulnerable to “peculiar temptations,” but also, because “the whole tendency of the situation of the Negro is to kill his self-respect,” black women thus lost the protective, saving benefit of “the greatest safeguard of female chastity.” The plight of black men thus led to the fall of black women to unchastity and promiscuity.41

Du Bois’s discussion of gender relations revealed the problematic presence of black women within black middle-class ideology. Glowing uplift ideals of motherhood were at bottom injunctions to monogamous marriage and domesticity. Black women’s respectability and moral authority were contingent on their relationship to black men. Thus, the requirement of black wives to tend families in the home signified progress for all concerned. Of course, the symbolism of the family and motherhood also had a compelling material and historical basis, as black men and women believed that it was preferable for a black woman to be supported and protected at home than to work for white employers outside it. Economic necessity, however, required many married black women to work to help support their families while also performing household duties.

Yet these ideals of home, family, and motherhood could just as easily be turned against black women, and all blacks. By condemning all black women outside of marriage, Du Bois echoed dominant assumptions of black immorality. He was hardly alone in assessing black women who did not live up to the status of respectable motherhood as morally suspect. If black men were slow to marry, a grave tendency that threatened “race suicide,” it was because black “women, by entering business and trades, have so reduced man’s means of a livelihood that, he finds the task of supporting a family a most difficult one. . . . The rule applies more to the cities than to rural districts where living is simpler.” From this perspective family stability required that black women withdraw from competition for scarce economic resources.42

A 1908 editorial from the Colored American Magazine entitled “How to Keep Women at Home” is relevant, although somewhat parodic in tone. It contains no explicit reference to black women, or race in general, but its very presence in a black publication indicates that it held significance for middle-class blacks. The author noted with growing dissatisfaction that “women will not stay at home,” choosing instead to frequent clubs, stores, theaters, societies, and lectures. The problem threatened “the final destruction of our American homes, because of its abandonment by its queen, the American woman.” Women’s independent behavior was clearly an affront to this author’s image of the civilized male: “Women are getting very bold, and instead of using the freedom that civilized men are allowing them, for adding to the comforts of man, they are abusing them. This is the thanks that civilized man is getting for giving his women more liberty than women get in half civilized countries. . . . And what is coming next nobody knows. Women always know how to take the ell if they are given the inch. They are selfish creatures and think everything a man has belongs to them because they tell him they love him.”43 For this writer, “freedom” for black wives means the leisure to stay at home and be supported, which, as we have seen, is no small task for the “civilized” black man. Interestingly, he resorts to an allusion to Frederick Douglass’s autobiography, describing women’s so-called freedom with words from Douglass’s bondage (“if you give a nigger an inch, he will take an ell”).44 Fulfillment of the white bourgeois ideal of separate spheres as a sign of advanced civilization requires that he keep his wife at home. His status and identity as a civilized, bourgeois male depends on it. The interesting thing here is how the emphasis on the male prerogative of woman’s place in the home serves to transcend race. To black men desirous of maintaining a middle-class, patriarchal identity, the attainment of economic independence usually meant protecting their wives from domestic service, and the threat of sexual abuse by white men. The author represses this anxiety, imagining instead a universalized male complaint against all women through which racial conflicts are suspended by invoking gender-related anxieties. This ideal arrangement, so “abused” by “selfish” women, represented the level of civilization, or upright moral behavior, that middle-class blacks had struggled to achieve, and which presumably distinguished them from “half-civilized” peoples.45

The Limits of Black Leadership

In addition to anxieties over patriarchal authority, Du Bois seemed at a loss to account for the agency and self-determination implicit in racial uplift ideals and what he regarded as the shortcomings of the leadership of “the better class.” He had a difficult time reconciling his ideals of a truly legitimate black leadership with existing institutions and leaders. Like many white progressives, he disapproved of machine politics, which were associated with corruption, patronage, drunkenness, and prostitution. At the same time, however, he admitted that politics afforded black men rare opportunities for status, power, and race pride. “What if some of these positions of honor and respectability have been gained by shady ”polities’ . . . ?” he asked. Consequently, he thought it too much to ask that blacks “surrender these tangible evidences of the rise of their race to forward the good-hearted but hardly imperative demands of a crowd of women.” Given that uplift ideology in some respects represented a style of reform that coincided with nineteenth-century evangelical notions of women’s moral influence, Du Bois’s mocking reference to white women reformers is ironic, but also indicative of his desire to protect nascent black political culture and institutions from such root-and-branch reform efforts.46

Generally, however, Du Bois was so adamant on the need for irreproachable, socially responsible black leadership that he went well beyond condemnations of machine politics, poor, desperate blacks, and “fallen” black women. The class stratification he observed among those black Philadelphians who had apparently succeeded in the struggle of getting a living appeared in some instances to him to be the antithesis of progress. Far from being guardians of purity, the black elite seemed to him to have been infiltrated by people whose ability to give an appearance of outward success nevertheless masked a basic moral delinquency. He noted that within the Seventh Ward, “intermingled with some estimable families, is a dangerous criminal class.” These were not the unemployed “low open idlers” of the slums, “but rather the graduates of that school: shrewd and sleek politicians, gamblers and confidence men, with a class of well-dressed and partially undetected prostitutes.” Ever vigilant, and preoccupied with rooting out all vestiges of impurity, Du Bois witnessed such “undesirable elements” in conducting his “house-to-house visitation” of the ward in 1896, noting every apparent transgression of uplift ideals and Victorian morals. Du Bois seemed concerned, to the point of distraction, with the anonymity of urban life, where the deceptive nature of outward appearances rendered his project of moral and social classification all the more dubious.47

Despite all his criticism of the morals of lower-class blacks, for the sake of delineating a black “better class,” Du Bois reserved his harshest judgments for the black community’s nominal leaders. He was disillusioned by the quality of black ministers because the church had historically been such a crucial institution serving “to promote the intelligence of the masses.” Although careful to insist that blacks were not “hypocritical or irreligious,” their church was “to be sure, a social institution first, and religious afterwards.” Having escaped the pietism of Wilberforce University, Du Bois believed black ministers fell short of the enlightened, reform ideals of uplift, forsaking “the chance to be a wise leader or a demagogue, or, as in many cases, a little of both.” He sarcastically viewed many ministers as “good representatives of the masses of Negroes,” followers instead of leaders. He likened black Methodist ministers to businessmen and politicians, “sometimes . . . inspiring and valuable leader[s] of men,” but at other times parasitic charlatans who induce “the mass of Negroes to put into fine church edifices money which ought to go to charity or business enterprise.” The reversal of moral values that brought “undesirable elements” into contact with respectable blacks had also contaminated black church life, which Du Bois perceived as antagonistic to home life. “The congregation does not follow the moral precepts of the preacher, but rather the preacher follows the standard of his flock, and only exceptional men dare seek to change this.” Seldom preaching an uplifting social gospel, the preacher often pandered to his congregation, and was on the average, “neither learned nor spiritual, nor a reformer.”48

The black minister had become the equivalent of the demagogic machine boss to Du Bois, who perceived a disturbing lack of vision among the race’s putative leaders. To him, the church life of black Methodists offered no more substance than the “host of noisy missions which represent the older and more demonstrative worship.” The negative impact of religion even extended beyond the church, extending into charity organizations: “A Young Men’s Christian Association which would not degenerate into an endless prayer meeting might meet the wants of the young men.” Even the A.M.E. Church Review, published in Philadelphia, the birthplace of the independent black church, while “probably the best Negro periodical” of its kind, was not above criticism. To Du Bois, the Review was “often weighted down by the requirements of church politics” and was obligated on occasion to publish “trash” penned by ambitious churchmen. Du Bois’s criticisms were indicative of the tensions within black leadership circles between the church and more secular ideals and institutions, embodied, for example, in the black press, in schools, and in the mass culture and entertainment industry.49

While lamenting the lack of truly exceptional men, Du Bois saw the deteriorating occupational situation for black entrepreneurs, tradesmen, and workers as further evidence of the abandonment and betrayal of white elites. As he found only inconsistency in his search for able black leadership, Du Bois also doubted that disinterested moral authority rested with so-called progressive whites. “There was,” he noted, “no benevolent despot, no philanthropist, no far-seeing captain of industry to prevent the Negro from losing even the skill he had learned or to inspire him by opportunities to learn more.” The benevolence to which Cooper and other black spokespersons had appealed had not materialized, as the “simple race prejudice” of both workers and capitalists provided the motive for the systematic exclusion of blacks from jobs. Du Bois denounced justifications of black exclusion that claimed that hiring blacks was bad for business.50

For Du Bois, Cooper, and progressive reformers in general, uplift was a matter of social equilibrium, of constructive, mutually rewarding relations between the classes of society, leaders and masses, and between the “better classes” of blacks and whites. Holding out little hope for improved race relations with white workers, black intellectuals such as Du Bois and Cooper were even more resentful of the contempt of those supposedly enlightened middle-class whites whose values they shared. Du Bois’s case studies in the section titled “Color Prejudice” showed enterprising, persistent blacks confronting the white monopoly on trades, clerical, and business opportunities in Philadelphia with few victories. “No matter how well trained a Negro may be,” he wrote bitterly, “or how fitted for work of any kind, he cannot in the ordinary course of competition hope to be much more than a menial servant.”51

A crucial problem of black leadership was its difficulty in reproducing black business and entrepreneurship across generations, a situation tied to the economic dependence of that class on white consumers and patronage. Prejudice and exclusion, while providing a market for such enterprises within the black community as funeral parlors, newspapers, grocery stores, hair salons, and restaurants, had thinned the ranks of those black barbers, caterers, and entrepreneurs who had thrived serving an upper-class white clientele. Although Du Bois bemoaned such economic isolation, he also realized the extent to which blacks’ “economic activities have been directed almost entirely to the satisfaction of the wants of the upper classes of white people.” The combination of a lack of business training, prejudice, and Du Bois’s observation that “Negroes are unused to co-operation with their own people” spelled dim prospects for black merchants. The disturbing void he found in his search for capable black leaders was evident here, too, as he saw a heroic antebellum generation of successful black entrepreneurs dying off. Indeed, as he lamented the tendency of the businesses of ambitious blacks to die with the charismatic personalities who built them, Du Bois also noted the additional impact of the ruthless competition of large enterprises on the small businesses of black entrepreneurs. Department stores and factories (whose jobs were generally closed to blacks) “almost preclude[d] the effective competition of the small store.” Du Bois found many obstacles to the reproduction of blacks’ wealth and enterprise across generations.52

In spite of everything, the burden fell upon blacks to improve their morals. Black homes “must cease to be, as they often are, breeders of idleness and extravagance and complaint.” The black middle-class concern for the preservation of family life, though related to middle-class white anxieties on the matter, arose from blacks’ sense of deprivation of secure homes and family relations that were immune from white invasion. The home was thus a sign of racial integrity and conservation, with unmistakable implications for the reproductive control of black women. Beyond it, blacks also faced, according to Du Bois, “a vast amount of preventive work,” mainly in chaperoning young women and girls and protecting them from the evils of the streets. Despite past and present hardships, blacks were required to make “every effort and sacrifice possible on their part” toward something achieving “complete civilization.” Du Bois’s skepticism regarding black ministers notwithstanding, he set for black leaders a messianic challenge of moral spotlessness and forgiveness.

Perhaps because he sensed few people were capable of bearing such a burden (and he would eventually tire of it himself), Du Bois saved for last a discussion of the duty of white Philadelphians, arguing that whites “must hold themselves largely responsible for the deplorable results” of discrimination. He baldly stated what his previous moralism against blacks had perhaps laid a foundation for: “Such discrimination is morally wrong, politically dangerous, industrially wasteful, and socially silly. It is the duty of the whites to stop it, and to do so primarily for their own sakes.” Whites also needed to realize that much of the “sorrow and bitterness” among blacks “comes from the unconscious prejudice and half-conscious actions of men and women who do not intend to wound or annoy.” Deeply attentive to the sentiments of whites, Du Bois appeared almost to be excusing his white middle-class audience, forgiving them in somewhat Christlike fashion for “unconscious” actions that caused unintended harm.53

The rhetorical strategy of Du Bois’s study, directed toward alerting reasonable, right-thinking whites to intraracial class stratification, and to the existence of a racially oppressive social environment, suggests the extent that blacks were judged guilty by the dominant culture, either as outright criminals or, perhaps more benignly, as an “undeveloped” people. Although he provided a subtle and innovative analysis of the psychological impact of race hatred on blacks, Du Bois made the dubious suggestion that it affected elite blacks more than others: “All this of course does not make much difference to the mass of the race, but it deeply wounds the better classes, the very classes who are attaining to that to which we wish the mass to attain.”54 Du Bois’s claim that black elites felt the sting of prejudice and exclusion more acutely than did less privileged blacks recognized white society’s backlash against black social advancement. But although he undoubtedly spoke from experience concerning “the better classes,” Du Bois’s distinction nonetheless illustrated the self-serving, class-bound assumptions of racial uplift ideology.

Yet even as Du Bois cited socioeconomic and historical causes in explaining black poverty, The Philadelphia Negro set the standard for a sociological version of racial uplift ideology. His study employs a view of class predicated on racial essentialism, displacing one rooted in social structures and power relations. Despite his thorough survey of discrimination, Du Bois echoed the general tendency to emphasize moral, behavioral issues of individual adjustment and assimilation to “modern civilization,” a euphemism that effaced the power relations reproducing class. In the aftermath of black migration to the North, this reformist discourse of uplift prized instrumental rationality in seeking “the adjustment of the Negro to the problems of urban life.” These urban “problems,” measured by family “disorganization,” were understood as deviations from blacks’ presumably natural state of rural life, which was assumed to be qualitatively better on the farm.

Such rural nostalgia, a mood reflected in The Souls of Black Folk, was rooted in a notion of an organic society, jolted out of its functional order by urbanization. But even within such conventions and sensibilities there was room for innovative social analysis. That work, interestingly enough, might be read as a critique of the sociological animus of its predecessor, and as an elaboration on some of its more effective analytical strategies. Denouncing the “car-window sociologists” whose superficial knowledge of the southern Negro owed more to minstrel stereotypes than careful study, Du Bois urged his readers not to forget that “each unit in the mass is a throbbing human soul,” and that the “great mass of them work continuously and faithfully for a return” under exploitative conditions. Du Bois’s discussion in Souls of the replacement of the landlord with the merchant—“part banker, part landlord, part contractor, and part despot,”—struck at the heart of the conditions of debt slavery in the “cotton kingdom” of the black belt. Noting the conditions of peonage, convict labor, laws prohibiting agents seeking to entice black migration, the paternalism that rendered black men powerless before the courts unless a white man, usually his employer, vouched for him, the prevalence of child labor, and the denial of public education, Du Bois insisted that these conditions of “modern serfdom,” not the proverbial charge of indolence, had sparked urban migration. “Such an economic organization is radically wrong,” he declared. “Whose is the blame?”55

In posing the question in this manner, Du Bois demonstrated a grasp of his white readers’ sensibilities that owed a great deal to Washington’s pseudo-empirical rhetorical style. Here Du Bois’s mode of analysis surpassed a racial essentialism designed to tighten the shackles on black labor. Du Bois challenged the widespread view, endorsed by Washington and so many others, of black indolence, countering that “a system of unrequited toil” was fatal to the industry and efficiency of black field hands: “Nor is this peculiar to Sambo; it has in history been just as true of John and Hans, of Jacques and Pat, of all ground-down peasantries.” However regressive his use of ethnic stereotypes, Du Bois’s comparison of the exploitation of black labor with that of European peasants attacked assertions that subservience to white employers was a racial trait of southern black laborers. Instead, Du Bois warned that crime and socialism (a telling juxtaposition) were inevitable within such an arrangement, and, by way of confirmation, offered an anecdote that seemed more indebted to underground black folklore than minstrelsy: “I see now that ragged black man sitting on a log, aimlessly whittling a stick. He muttered to me with the murmur of many ages, when he said: ”White man sit down whole year; Nigger work day and night and make crop; Nigger hardly gits bread and meat; white man sittin’ down gits all. It’s wrong.’” Here, Du Bois was revising Washington’s text, and his own. His discussion of class stratification among African Americans in the black belt was strictly economic, representing an advancement from the racialism implicit in his stress on gender relations, patriarchal authority, and sexual morality as the measure of class stratification in the Philadelphia ghetto.

In noting both the similarities and subtle, yet crucial differences in Du Bois’s perspective that are evident in the shift from northern urban to southern rural fields of inquiry, it is imperative that we distinguish between the impact of situational identity along with the additional movement of history on Du Bois’s intellectual production, and the less reflective processes inherent in the institutionalization of a sociological discourse of uplift, which, despite its environmental impulse, nonetheless carried racialized overtones. That said, the main contribution of Du Bois’s study—its environmentalism—was generally undermined by its anxiety over the morals of black migrants to the city, particularly single black women, whose existence outside the family threatened reproductive norms that privileged paternity. This approach represented the intertwining of older pietistic and secular outlooks in the evolving professional uplift discourse, whose moral prescriptions, inherited from dominant cultural codes, cannot be understood apart from the social conflicts of industrialization, racist social science, and even minstrel vulgarisms.56 At any rate, the academic sociological discourse of uplift, the urban counterpart to industrial education, called for the supervision and adjustment of black workers to industrial capitalism by social work professionals, who also sought to inculcate a complementary domesticity for black women. In short, this “black” sociological approach echoed mainstream notions of social pathology, measured not solely by family disorganization but also in accordance with the view that urban pathology entailed a failure to reproduce an industrial labor force.57 Descended partly from the approaches of both Du Bois and those of reformers and academics, the sociological component of uplift ideology was promoted within the sociology departments of the University of Chicago, as well as Fisk, Atlanta, and Howard Universities. Subsidized by foundations and other forms of white philanthropic largesse, variants of it would remain influential within professional and journalistic discussions of race, migration, reform, and urban poverty well into the twentieth century.

Upon completion of his research in Philadelphia, Du Bois established a sociology program for both graduates and undergraduates at Atlanta University. His series of social studies, produced from 1896 to 1914, rarely met the standard set by The Philadelphia Negro, due to a lack of funds and the necessity of using untrained assistants. Still, it represented the only work of its kind and attracted wide and sometimes favorable comment. In 1900, Du Bois used his studies to prepare for the Paris Exposition an exhibit of the social progress of black Americans that won universal praise from the American press and the exhibition’s grand prize for its author.58

A year before, however, Du Bois’s faith in dispassionate social research had been irreparably shaken by the lynching of Sam Hose, a black sharecropper, in the outskirts of Atlanta. While carrying a letter to the Atlanta Constitution defending Hose against charges of rape, Du Bois learned that Hose, who had killed his landlord in a dispute over payment for his crop, was taken from jail, tortured, and lynched. “I began to turn aside from my work,” Du Bois recalled. In another memoir, he recalled the impact that his return to the South and its brutal customs had on him: “One could not be a calm, cool, and detached scientist while Negroes were lynched, murdered and starved.” In addition to what he called “the crucifixion of Hose,” the racial violence of 1898, with the Wilmington riot, the killing of postmaster Fraser Baker, and the mistreatment of Negro soldiers in the recent war surely played a part in his shift to a more militant posture.59

Another outbreak of racial violence—the riot in Springfield, Illinois, in 1908, would provide the catalyst for Du Bois’s transition from academic to agitator, and his subsequent career with the NAACP. Its contradictions notwithstanding, The Philadelphia Negro demands our recognition of its continued relevance, as urban blacks still contend with disproportionate poverty, ill health, unemployment, and inadequate city services, with their life chances additionally restricted by de facto residential segregation and ineffective public schools. “How long can a city teach its black children that the road to success is to have a white face? How long can a city do this and escape the inevitable penalty?” wondered Du Bois in 1899.60 Perhaps because we cannot read it today without perceiving the limitations of bland assertions of racial progress and uplift, The Philadelphia Negro retains a sobering, prophetic impact that Du Bois could not have foreseen.