7: From Freedom to Slavery

Paul Laurence Dunbar, James D. Corrothers, and the Ambivalent Response to Urbanization, 1900—1916

She’s the leader of the color’d aristocracy

And then I’ll drill these darkies till,

They’re up in high society’s hypocrisy

They’ll come my way to gain entree . . .

To the circle of the color’d aristocracy.

When dey hear dem ragtime tunes, White folks try to pass fo’ coons on Emancipation day.

As we have seen, the dread of racial stigma colored much of what the black intelligentsia did or said about the so-called Negro problem. Still, black intellectuals found ways to challenge white constructions of blackness: Ida B. Wells, Anna Cooper, W. E. B. Du Bois, J. Max Barber, T. Thomas Fortune, and many others were able to do this, on occasion. Omnipresent as it was, however, racism might be challenged, but not easily refuted. As we have seen with the confluence of minstrelsy and social science conceptions of pathology, the urban setting was the location upon which black writing on race waxed apologetic or, at best, ambiguously oppositional. At the turn of the century many black intellectuals and leaders expressed alarm at the impact of urbanization, migration, and the homogenizing forces of mass, consumer culture on the black community. Like many bourgeois whites, they associated tenements and slums with social and cultural decay. For blacks, social change also meant challenges to religious traditions of black leadership and authority by new secular pastimes and attractions. As early as 1885 Alexander Crummell noted with dismay what he saw as “an addiction to aesthetical culture as a special vocation of the race.” To Crummell, such secular cultural and artistic activities had come at the expense of strengthening the family and improving the conditions of labor and morals for blacks. Curiously, however, Crummell held the black poet Paul Laurence Dunbar in high regard, despite the fact that Dunbar was implicated by the commodification of blackness in mass culture industries of literature and musical comedy.1

Well before the major urban migration of Southern blacks to the North during and after World War I, the black population in northern centers like Philadelphia and Chicago increased substantially. In New York, the black population grew by twenty-five thousand between 1890 and 1900. Real estate agents were often unconcerned with preserving the middle-class character of black neighborhoods and profited from the residential segregation that produced crowded slums. This, combined with municipal policies confining prostitution, saloons, and gambling to black sections, away from white residential and commercial areas, led elite blacks to see a correlation between urbanization and moral chaos. The Chicago clubwoman Fannie Barrier Williams thus described the struggles of the black elite: “The huddling together of the good and the bad, compelling the decent element of the colored people to witness the brazen display of vice of all kinds in front of their homes and in the faces of their children, are trying conditions under which to remain socially clean and respectable.” Williams was hardly alone in her concern to demarcate with utter clarity their moral and class superiority over the faceless, penniless “greenhorns” and the various pretenders to elite status among black newcomers to the urban scene. And class anxieties were exacerbated by the racial violence that erupted in New York in the summer of 1900 as blacks were mobbed and beaten in the West Sixties’ San Juan Hill district by Irish gangs and police.2

This influx of southern blacks, combined with European immigration, into cities already fraught with explosive labor strife throughout the 1890s had heightened general fears for the maintenance of social order. Northern migration—“voting with one’s feet”—provided one of the few opportunities for powerless, impoverished blacks in the Deep South to escape subordination. To many elite blacks, however, the movement to the North had worsened the black elite’s already considerable sense of dislocation. Themselves ill-equipped to assist the migrants, they were largely incapable of viewing the migration positively. Their outlook, rooted in the philosophy of industrial education, often characterized blacks as disorderly, unfit for citizenship, superstitious, criminal, lazy, immoral, and needing to be compelled to work. White supremacists and even some of their moderate allies had argued along similar lines that blacks needed to be discouraged from migrating, and controlled through racial segregation, or more drastic measures.3

Unaware that more privileged elements were well represented among black migrants, elite blacks feared that urban leisure and consumerism were undermining the eternal verities. In this, they were strongly influenced by culturally dominant fears of black immigrants. The migration had a corrosive effect on black institutions; Orishatukeh Faduma, a West Indian-born pan-Africanist educated at Yale, criticized the black church for its “outwardness” and what he saw as its lack of enlightened spirituality. The urban black church promoted materialistic values and a tendency among worshippers of “valuing oneself from appearance” and making religion “a puppet show.” Several black commentators even relied on minstrelsy’s debased images of blackness to disparage the trend of migration and the urban proletariat it produced. Such jeremiads by members of the black intelligentsia reflected their own marginality and their bid for cultural authority. At the same time, however, their criticisms arose from the deep conviction that in a racist society, it was incumbent on African Americans to adhere to standards of moral perfection. Still, the question remained, precisely who set the standards for the proper moral conduct of African Americans in cities?4

Dunbar, whose lyrics and stories often portrayed the simple joys of pastoral life, offered a bleak assessment of the condition of urban black migrants. In an account of “The Negroes of the Tenderloin,” Dunbar summoned all his literary powers to sketch a lurid Darwinian vision of moral peril. The crowds of “idle, shiftless Negroes” he observed there led him to despair that nothing could be done to prevent them from “inoculating our civilization with the poison of their lives.” They cared nothing for socialism or anarchism, and yet, these seemingly “careless, guffawing crowds” posed a “terrible menace to our institutions.” Their environment promoted crime and obliterated the moral sense, and the occasional “mission,” or social settlement, was as inadequate as a gauze fan against the furnace blasts of hell. Black migrants to New York were “giving up the fields for the gutters,” the “intelligent, moral and industrious” class of blacks was powerless to rescue these fallen masses, and although Dunbar feared for civilization, he expressed pity for the defenseless migrants. Until they demonstrated a better capacity for urban civilization, he concluded, “I would have them stay upon the farm and learn to live in God’s great kindergarten for his simple children!” As with other black commentators on the subject, Dunbar’s perspective was informed by the plantation legend, which held rural surroundings as the natural environment for undeveloped African Americans.5

Dunbar’s observations on the black residents in the Tenderloin are even more intriguing when superimposed against what is known of his personal life. He divided his time between New York, where his fiancée, Alice Moore, lived and taught in Brooklyn, and Washington, D.C., where he worked as an assistant in the Library of Congress reading room. Paul and Alice were married in 1898 after a long and difficult courtship, prolonged by their separation, the opposition of her parents to the engagement on grounds of class and perhaps color, and tensions related to Dunbar’s alcoholism. After a brief honeymoon, they returned to their respective homes. As a popular “literary lion,” Dunbar toured the country giving readings and was worshipfully feted by black socialites. Knowing him better than others, Alice was concerned about his reputation, and clearly, hers as well. Just before their wedding, Alice had implored him to avoid the Tenderloin when he visited the city. “I want you to be dignified, reserved, difficult of access,” she wrote, and she bluntly urged him to keep away from the section’s undesirables, the category in question rendered with a choice epithet so as to avoid misunderstanding. It appears that Dunbar’s personal frailties and his constant touring prevented the realization of Alice’s hopes for their marriage. But she had her own ambitions. Besides her employment, Alice held literary aspirations as a poet, essayist, and author of short fiction.

As his writings, and records of his relationship with Alice suggest, Dunbar was deeply ambivalent, if not tortured, on matters of race and class. Although a national celebrity and a culture hero for African Americans since his recognition by the literary critic William Dean Howells, he chafed at the popularity of his dialect poems. There is enough evidence to suggest that despite his fame, Dunbar bore considerable despair for which his intimate relationships provided little relief. In 1899, he contracted a disease reported as pneumonia, and Alice nursed him back to a semblance of health and took charge of his business affairs as a collection of her own stories, The Goodness of St. Rocque, was published by Dodd, Mead and Company. In 1902, the Dunbars separated, and they remained unreconciled at the time of Dunbar’s death in 1906 of tuberculosis. James Weldon Johnson, who greatly admired Dunbar, recalled that beneath the latter’s politeness dwelled a “bitter sarcasm,” adding that Dunbar felt aesthetically limited by incessant demand for his dialect poetry. Dunbar’s reputation was the captive of whites’ fixed image of blackness as minstrelsy, a view that pursued him to the grave. The Southern Workman’s obituary carped that “his work in dialect seems to us far superior to his other writing and his special talent was for poetry rather than prose.”6

Given what is known of his personal history, Dunbar’s views on black migration provide a striking context for a reading of his 1902 novel, The Sport of the Gods, which assayed urban life among African Americans in New York City. Although the novel conveyed a gloomy apprehension toward the debased ideals of urban black youth, and voiced the usual contempt for the black and white pleasure seekers who inhabited the city’s cabarets, his naturalistic treatment of these issues was much more complicated than the stance of outright condemnation he and others took elsewhere. Whatever his motives in penning the newspaper sketch, it is clear that Dunbar, the son of former slaves, lived at the margins of the black leisure class and of racial uplift ideology. Although he, as the rising poet of the race, had spent many social hours with the intellectuals of the American Negro Academy and Washington, D.C., black society, he could simultaneously bask in their attention while maintaining a fascination for “low life” that others, particularly Alice, would find abhorrent. Dunbar conformed to, but was skeptical of the uplift pieties voiced by many black spokespersons. It wasn’t only that black elites were powerless to dissuade southern blacks from coming north. Even more decisive for Dunbar was the sense that uplift’s self-help, leadership ideals paled before the magnitude of social conditions in cities.

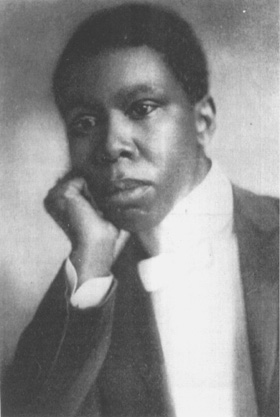

Paul Laurence Dunbar, ca. 1900.

As some of the Harlem Renaissance writers were to discover years later, creative intellectuals like Dunbar found that their productivity and livelihood were seldom free from the constraints of white audiences and patronage. Dunbar applied these lessons in The Sport of the Gods, manipulating and challenging the conventions of plantation fiction that had characterized much of his work. His struggles for creative integrity led him to pursue a comprehension of the historical and social relations that underlay class relations among blacks that bordered on parodic treatments of the verities of racial uplift and migration.

Northern writers such as Dunbar and his contemporary, James D. Corrothers (1869—1917), a minister, journalist, and poet based in Chicago, charted alternative paths in African American literature away from the didactic historical fictions of writers such as Pauline Hopkins and Sutton E. Griggs. They, along with James Weldon Johnson, tackled difficult subjects and grounded their work in the mass culture of Progressive Era journalism and popular music and stage shows, whose racial content, minstrel trappings, and working-class settings writers of uplifting race literature would have scoffed at. Ironically, such writings caught on with white audiences predisposed to seeing their authors as “authentic” black writers of dialect verse derived from the plantation and minstrel stereotypes of urban blacks. There were obvious pitfalls to such an approach. Any divergence from sentimentalized white perceptions of blackness might inspire a dismissive review such as the one Dunbar received in the Independent in 1899: “The negro, pure and simple, is not here.”7 Both Dunbar and Corrothers expressed frustration with the mass publishing market’s hostility to their more assimilationist literary aspirations. They shared a tragic awareness of the failures inherent in the success bestowed only on those black writers who worked within demeaning literary and popular conventions.8

Given their willingness to both exploit and flout both dominant and oppositional racial conventions, Dunbar and Corrothers condemned themselves to marginality within the discourse of uplift, which tended to stress positive portrayals of blacks as paragons of success and refinement. Yet they also shared a deep interest in representing the impact of urbanization on cultural and class divisions, and aspired to a level of social realism that William Ferris, for one, would have termed pathological. More than many of their contemporaries in literature, they were exploring social and cultural change and scrutinizing its effects. Their urban writings seem all the more adventurous when compared with W. E. B. Du Bois’s figuration of a vanishing black rural folk culture, which emphasized, along the lines of the Volksgeist of German nationalism, the folkloric and musical expression of African Americans’ racial soul.

Du Bois’s conception in The Souls of Black Folk of African American folk culture embodied in the slave spirituals—the “sorrow songs” sung by those “who walked in darkness,”—makes an interesting comparison with Dunbar’s invocation of the plantation legend in his discussion of urban blacks in the Tenderloin. By equating spirituals with the Volkslied of German romanticism, Du Bois departed from minstrelsy, creating an international context for his definition of black high culture. He was determined to distinguish from minstrel songs what he called “not simply . . . the sole American music, but . . . the most beautiful expression of human experience born this side the seas.” To his aesthetic argument that held the spirituals as proof of black beauty and humanity “as the singular spiritual heritage of the nation and the greatest gift of the Negro people,” Du Bois added a folkloric argument for race progress. Drawing on what he felt to be the omissions and silences of the spirituals, he noted that “mother and child are sung, but seldom father; fugitive and weary wanderer call for pity and affection, but there is little of wooing and wedding; the rocks and the mountains are well known, but home is unknown.” Even as Du Bois believed the spirituals would affirm blacks’ claim to equal rights (“Actively we have woven ourselves with the very warp and woof of this nation. . . . Would America have been America without her Negro people?”), hoping that “America shall rend the Veil and the prisoned shall go free,” his sense of loss at the songs’ absence of patriarchy allowed him to contrast folk traditions with uplift’s prescription for the race’s arrival into the fatherland of modernity through patriarchal home and family life. The force of Du Bois’s argument for African Americans’ humanity is not diminished by the realization that in a society uncontaminated by racism such arguments would have been unnecessary. Still, Du Bois’s vision of the spirituals operated at several levels: as an appeal for recognition, an affirming claim of cultural autonomy, and a construction of African-Americans’ collective messianic purpose in redeeming American democracy.9

Du Bois’s renaming of black folk culture using the spirituals as the Negro equivalent to Germanic folk culture came at a time when European composers were adapting folk melodies for orchestral music, and it represented a flight from the pejorative racial connotations of American minstrelsy and the urban setting. Although Du Bois praised the Fisk Jubilee Singers as the true bearers of the spirituals, he noted the all-too-frequent “debasements and imitations—the Negro ”minstrel’ songs, many of the ”gospel’ hymns, and some of the contemporary ”coon’ songs.” The potential for misunderstanding was magnified by the fact that virtually every southern black educational institution sent out a vocal group of this sort for fundraising purposes. Along with the spirituals, some of these groups performed minstrel and vaudeville songs and routines. One such group was the Dinwiddie Quartet, organized to sing on behalf of the John A. Dix Industrial School of Dinwiddie, Virginia. Founded in 1902, they toured in support of the institution, went into vaudeville, and disbanded in 1904. James Weldon Johnson had such deviations from the assimilationist cultural aesthetic of uplift in mind when he wrote, in 1928, “Many persons . . . have heard these songs sung only on the vaudeville or theatrical stage and have laughed at them because they were presented in humorous vein. They have no conception of the Spirituals. They probably thought of them as a new sort of ragtime or minstrel song.”10

While well acquainted with black bourgeois values, Dunbar, Corrothers, and even Johnson, along with those quartets that straddled the line between spirituals and minstrelsy, were less than wholly faithful to elite Western cultural values. Dunbar, writing in the Saturday Evening Post, had urged whites to recognize the existence of an exclusive black leisure class in Washington, D.C., but his days there and in black Manhattan brought home for him an understanding of the rhetorical nature of the dichotomy between “the classes” and “the masses,” and its irrelevance in the face of white violence. Dunbar had himself visited San Juan Hill in an attempt to quell the bloody violence of 1900. For Corrothers, such class distinctions, based largely on character, were fodder for satire, except where he employed them to his personal advantage in his autobiography. In Dunbar’s novel, and in Corrothers’s autobiography In Spite of the Handicap (1916), these writers examined the extent to which white betrayal and exclusion had not produced an ameliorative class differentiation, as other writers had insisted, but instead, bitter internecine conflict and resentment within the black community. Their works illuminated the dirty laundry of internal conflicts that uplift ideology had sought to explain away.11

Incorporating not simply dialect but also aspects of black vernacular and popular culture into their writing, Dunbar and Corrothers sought to hold a mirror up to social and cultural change in their work, rather than merely rail against it. In this they departed from the prevailing moralistic approach to urban black society. As precursors to the literary activity that emerged out of New York and Chicago after World War I, they and others were more receptive than older black intellectuals to literary experimentation that incorporated popular forms and addressed changing social conditions in novel ways. Corrothers was a keen observer of the cultural diversity of ethnic politics in Chicago in the 1890s. His writings represented the competitive struggles of working-class, immigrant whites and blacks who occupied the same morally charged urban public spaces in the Progressive Era, with saloons and other disreputable enterprises becoming bases for political influence and entry into machine politics. Dunbar and Corrothers refigured and broadened racial representations with secular, critical positions that addressed the inconsistencies of uplift ideology as a blueprint for black progress.12

Dunbar’s Sport of the Gods is yet another meditation on the theodicy of American racism, its title serving as an ironic displacement of the narrative’s sustained critique of whiteness, and the institutional apparatuses that upheld white privilege, particularly the courts. Dunbar addresses the social and cultural pressures facing the black community, North and South, both internally and from without. Like the work of William Ferris, the novel reads almost as an atonement for previous failures and transgressions, and an act of self-justification. It spans blacks’ historical movement from the rural South to cities, the destination being New York, the mecca of all aspiring young men and women from the provinces, much as it had been for the Ohioan Dunbar, and for many others, including such southerners as T. Thomas Fortune and James Weldon Johnson. Dunbar endorsed the prevailing view among prominent blacks that this move to the cities was hardly progressive, although he made the move himself.

The ineluctability of Dunbar’s account of the disintegration of a black family, combined with his title, has led several critics to dwell on his unrelieved pessimism and the complete subordination of his characters to fate. The novel’s sense of the futility of human agency against inexorable social and economic forces shared the bleakness of the novels by Theodore Dreiser and Frank Norris. The novel has more in common with these works of social realism than with the optimism of the uplift romances of Pauline Hopkins and the autobiographical success stories of Booker T. Washington and Amanda Smith. But as D. D. Bruce has argued, such an emphasis on a relentlessly deterministic fate blatantly ignores Dunbar’s confrontation with that other form of human agency—oppressive white power and societal racism. Dunbar systematically attacks legal injustice, myths of southern paternalism, evolutionary theory, and the cynicism of yellow journalism. Having constructed an all-too-real fictional universe of societal prejudice, Dunbar ironically (for reasons to be more fully discussed later) describes hapless black migrants as “the Sport of the Gods.”13

Dunbar’s depiction of the novel’s central characters, the Hamilton family, captured the struggles of right-living, pious southern blacks to maintain a modicum of security. In an unspecified location, probably in the upper South, Berry and Fannie Hamilton met and married in their earlier lives as slaves, and after emancipation, remained as servants for the southern white planter and businessman Maurice Oakley. With their children, Joe and Kitty, the Hamiltons made their home in the little servant’s cottage in Oakley’s yard. Eighteen-year-old Joe worked as a barber for the town’s white gentlemen, and Kitty, an attractive and well-attired sixteen year old, sang recitals for the AME church and her father’s lodge. The family’s security was shattered when Berry was accused of theft by Oakley at a farewell dinner for Oakley’s weak-willed younger brother Francis, who was leaving for Paris to become an artist.

In Dunbar’s scheme of social relations, white mistrust, betrayal, and moral cowardice were clearly implicated in the Hamiltons’ exile from the South. Francis, a womanizing dilettante, in Dunbar’s words, “an unruly member,” had gambled his money away, and unable to confess the truth, claimed he had been robbed. Berry conveniently becomes the prime suspect, and the pallid Francis watches his swift arrest in silent horror. When it is learned that Berry has eight hundred dollars in the bank, this is used against him, although his life’s savings was in small bills and coins. In Dunbar’s New South, the virtues of thrift could just as easily incriminate blacks, as Oakley’s paternalism turned into hateful prejudice in an instant. When a piece of circumstantial evidence proves decisive, Dunbar’s omniscient narrator wryly observes, “Frank’s face was really very white now.” As if Dunbar’s sly rendering of whiteness as duplicity had dawned on him, a disbelieving Berry, his final appeal to the trust and goodwill of his employer rejected, exploded, “Den, damn you! damn you! ef dat’s all dese yeahs counted fu’, I wish I had a-stoled it.” Berry’s tirade, voiced by Dunbar in dialect, undermined the sentimental plantation tradition, with its paternalistic assumptions of happy, docile blacks. By inscribing a dissonance between dialect form and angry content, Dunbar may have also wished to justify his previous dialect writings to himself and those blacks, including his wife, Alice, who had equated them with demeaning minstrel stereotypes.14

Dunbar’s narrative flatly rejected the paternalistic claims of New South spokespersons that the white people of the South were the Negro’s best friends. Even more relevant to this critique was his view that the Hamiltons, while privileged within the black community, were so dependent on white power that they could hardly be accurately described as middle-class. In addition, sisterhood proved no match for patriarchy tarnished with the self-righteous arrogance of whiteness, as Fannie’s desperate appeal to Mrs. Oakley for clemency fell on unsympathetic ears. Maurice Oakley had his servant jailed, and evicted his family from their cottage, hours after they had enjoyed the leftovers from the previous night’s dinner.

Oakley’s willingness to divide and disperse the Hamiltons suggested that enslavement had never ended for southern blacks. Dunbar described the tenuous status of those who may have existed in lordly relation to poorer blacks, but always at the sufferance of more powerful whites.15 As house servants to the Oakleys, the Hamiltons had been upstanding, if secretly envied, members of the black community. Having incurred the whites’ displeasure, however, their downfall unleashed the hostility of those blacks in whom “the strong influence of slavery was still operative . . . with one accord they turned away from their own kind upon whom had been set the ban of white people’s displeasure.” The AME church “hastened to disavow sympathy with him, and to purge itself of contamination by turning him out.” Here, class differences, or rather, the resentments among those for whom privileged status was merely a heritage of slavery, were seen as anything but progressive. If their neighbors had any sympathy at all for the high-toned Hamiltons, they dared not show it. “Their own interests,” Dunbar wrote of the Hamiltons’ neighbors, “the safety of their own positions and firesides, demanded that they stand aloof from the criminal.” In his eyes, respectability, class differentiation, and the protection of secure homes and firesides were hardly unmixed assets for the race. The security of such homes, hard-won prizes from a punitive white society, seemed inescapably tied to the dispossession and homelessness of others. Among vulnerable blacks, such misfortune was commonly explained not so much by legal racism as by the absence of a virtuous reputation that had distinguished the privileged few.16

Dunbar extended his criticism beyond the dependency of a black community, divided by moralism and resentment. These effects of oppression were part of a parodic treatment of those racist evolutionary theories that had informed the views of not only whites, but also, many a black spokesman. In a chapter mockingly entitled “The Justice of Men,” Dunbar staged a discourse on race relations among whites “at the bar of the Continental Hotel.” Here, with faculties of reason unhinged by whiskey, the Old South’s self-righteous racism and moral decadence are seen to be well preserved. Talbot, an old southern gentleman “who was noted for his kindliness towards people of color,” advanced a deterministic view of powerless blacks overwhelmed by fate. The Hamiltons, indeed, the slaves, should never have been freed in the first place, so unfamiliar were they with freedom and responsibility: “They are unacquainted with the ways of our higher civilisation, and it’ll take them a long time to learn. You know, Rome wasn’t built in a day.” Reflecting the prejudice masked by the seigneurial benevolence of Maurice Oakley, Talbot’s paternalism was actually not so distant from that of his drinking partner, “Mr. Beachfield Davis, who was a mighty hunter.” Davis insists, offering a clue as to what his hunting preference was, that “it’s simply total depravity, that’s all. All niggers are alike, and there’s no use in trying to do anything with them.” Where some black writers had accepted and internalized racist evolutionary discourse in their discussions of class distinctions, migration, and vice and immorality among blacks, Dunbar attacked the stereotypes at their source, spelled out the implications of their dehumanizing logic, and repudiated their authority.17

After the Hamiltons are driven from the Oakley house, all their efforts to find work and a new home come to naught, despite their innocence, within a black community obsessed with respectability. Already throwing off the religious piety of his parents’ generation, Joe proposes that the family move to New York, “a city that, like Heaven, to them had existed by faith alone.” What awaited the Hamiltons there made a mockery of the Christian idealism of the spirituals to which Dunbar sarcastically alluded. Despite Fannie’s misgivings, the family moved and settled into a rooming house, where William Thomas, an urbane railroad porter, promptly took an interest in them, especially Kitty. Dunbar described Thomas as “a loquacious little man with a confident air born of an intense admiration of himself.” Dunbar described Thomas, not coincidentally the namesake of the black man who had published that scandalously antiblack book of essays in 1901, as “the idol of a number of servant-girls’ hearts, and altogether a decidedly dashing back-area-way Don Juan.” Dunbar’s disdain for Thomas, who “looked hard at Kitty,” and eagerly offered to introduce the new arrivals to the dubious pleasures of ragtime, buckets of beer and coon shows, was evident.18

Historical references aside, Dunbar’s novel seemed propelled by autobiographical concerns. New York cabaret life was a world that Dunbar knew intimately, and a site charged with Dunbar’s ambivalence around black culture. Dunbar’s assessment of black musical comedy reflected the frustrations he experienced as an aspiring poet working both within and against the stereotyped expectations of white audiences. His account of the musical “coon shows” was deeply ambivalent. He saw value in blacks performing their own syncopated songs and dances for black audiences even while it galled him that they so avidly consumed the stereotyped entertainments that he believed were foisted on them. The avid interest of the audience indicated a popular desire for an autonomous cultural sensibility not unlike that which Du Bois located in the spirituals. Quite possibly the audience revelled in the display of black performance styles; moreover, in such a setting, their minstrel trappings may have been appealing partly by virtue of their parodic tweaking of black bourgeois pretensions. Dunbar was disinclined to ruminate at length on such matters, noting that the blacks in the audience, “because members of their own race were giving the performance . . . seemed to take a proprietary interest in it all.” The theater, while garish and cheap, looked “fine and glorious” to the Hamiltons, whose less than exalted standard had been set by the filthy “peanut gallery” of their segregated southern theater. Dunbar’s description conveyed his deep ambivalence over his own involvement in such productions, and over his poetic struggles, waged within the formal restraints of dialect: “They could sing, and they did sing, with their voices, their bodies, their souls. They threw themselves into it because they enjoyed and felt what they were doing, and they gave a semblance of dignity to the tawdry music and inane words.” Like caged birds, the black performers on stage were struggling heroically to break out of the insipid material. Still, despite his sympathy for the performers, Dunbar regarded popular entertainment as an opiate for the masses. Kitty found the spectacle enchanting, and “if ever a man was intoxicated, Joe was.” In Dunbar’s mind, at least for the moment, assimilationist critical standards, and the desire to distance himself from the crude coon songs, held sway. Ragtime, dancing, and dialect were of the same inferior order to him. Later, with the setting transported to a black nightclub, a slumming white journalist, watching couples dance to ragtime music, remarks that “dancing is the poetry of motion.” His black companion, a dour man nicknamed Sadness, sardonically replies, “And dancing in rag-time is the dialect poetry.” Dunbar had a difficult time distinguishing the creative possibilities of black culture from his hostility toward its consumption by uncultivated blacks and deluded white tourists and its expropriation by white popularizers—journalists, composers of coon songs, and publishers—the latter lured by their stereotyped, popular images of “authentic” negroness. Such feelings were no doubt complicated by Dunbar’s own role in promoting the genre: he himself had written the book and lyrics to “Senegambian Carnival,” an all-black show starring the popular comedy team of Bert Williams and George Walker.19

A Victorian sense of sexual propriety, and a vaguely expressed disapproval of the sexual objectification of light-complexioned, “high yellow” black women, informed Dunbar’s portrayal of events both onstage and in the audience. The narrative turned swiftly from the performance on stage, and Joe and Kitty’s rapturous enjoyment of the show’s “delusions,” to Mr. Thomas, who “was quietly taking stock” of Kitty, “of her innocence and charm.” In this garish setting of tawdry ideals and illicit pleasures, anonymous members of the audience were as much of a spectacle as the chorus of fair-skinned black women. Dunbar described the predatory gaze of Thomas, condemning the latter’s designs on Kitty, as well as the status light-complexioned black women companions conferred on black men. Still, Kitty stood a greater chance of resisting Thomas’s seductive attentions than did Joe, who was “so evidently the jest of Fate.” Mitigating this deterministic view, however, Dunbar added that in Joe’s job as a barber for whites in the South, he had “drunk in eagerly their unguarded narrations of their gay exploits,” and thus had begun “with false ideals as to what was fine and manly.” The “moral and mental astigmatism” Joe inherited from the white “wild young bucks” of his hometown found its counterpart in the admiration Thomas elicited from passing acquaintances whose tastes were equally suspect: “I wonder who that little light girl is that Thomas with tonight? He’s a hot one for you.”20

The musical stage and cabarets constituted an underworld where jaded hustlers preyed upon naive, impressionable young men like Joe. Hoping to insinuate his way into Kitty’s affections, Thomas introduced Joe to his gambling associates at the Banner Club. Capitalizing on Joe’s eagerness to prove himself as a man of the world, the gamblers “treated him with a pale, dignified, high-minded respect that menaced his pocket-book and his possessions.” Over several rounds of drinks, the men welcomed Joe as an old friend. In a didactic aside, Dunbar noted that the Banner Club “was an institution for the lower education of negro youth,” attracting people of all races and classes. “It was the place of assembly for a number of really bright men, who after days of hard and often unrewarded work came there and drunk themselves drunk in each other’s company, . . . and talked of the eternal verities.” Dunbar exhibited a bohemian’s mordant compassion for those with defeated aspirations, whose troubles could not be fully explained by personal weakness. Throughout the novel, such ironic moralism often functioned for Dunbar as a stoic shield against his own disappointments and alienation.21

Joe’s downfall is almost complete. He is fleeced by the gamblers, drinks heavily, and takes up with a showgirl, Hattie Sterling, who is the only trustworthy, decent character at the Banner Club. Hattie tries to help Joe recover his senses, and perhaps her character provided Dunbar an outlet for autobiographical reflections on his relationship with Alice.22 Be that as it may, Joe cannot be rescued from his disastrous course, and when Hattie finally leaves him, he murders her in a drunken fit of rage and goes to prison. Watching Joe’s descent helplessly, Mrs. Hamilton tries to save Kitty, and is devastated when, encouraged by Hattie’s coaching, she begins to perform on the musical stage. Lacking the financial support of her children, Mrs. Hamilton marries a boarder, in an unhappy, abusive union that Dunbar describes as purely utilitarian. Meanwhile, years after Berry’s imprisonment, Francis confesses his guilt and Berry’s innocence in a letter to his brother Maurice, who, although stricken feeble with the news, stubbornly refuses to let the truth be known. Through an unlikely sequence of events, Skaggs, a white journalist who frequented the Banner Club and had witnessed Joe’s dissipation, investigates Berry’s case, and sensing adventure and a scoop, heads south. He storms upon the Oakleys, and seizes the letter of evidence from Oakley (in the process fending off Mrs. Oakley, who attacked him with teeth and nails, “pallid with fury”). The sensational exposé he writes for his newspaper secures Berry’s release from prison. Dunbar notes that the “yellow” paper’s apparent liberal progressivism in gaining Berry’s release was motivated by little more than commercial opportunism. The novel’s bleak conclusion found Berry and Fannie reunited, after the opportune passing of Fannie’s second husband, and back at their cottage near the Oakley house, where they spent many nights thereafter “listening to the shrieks of the madman across the yard and thinking of what he had brought to them and to himself.”23

The utter pessimism over the state of race relations of Dunbar’s novel is only slightly relieved by his narrator’s ironic tone. Indeed, Dunbar seemed so thoroughly disenchanted with the urban scene that irony presented to him the only viable response to the resignation and helplessness of his characters. This ironic voice surely blunted the force of his social criticism, giving his jaded omniscient narrator some distance from his unpleasant tale. That same stance of withdrawal was served by his ironic title. For the entire plot of his novel contradicted the premise of resignation to an omnipotent divine will. If anything, human depravity and white exploitation wrecked the Hamiltons’ lives and were the root of the problem of evil, according to Dunbar. In a pivotal passage revealing Dunbar’s skepticism toward uplift pieties, the disreputable gamblers of the Banner Club, the architects of Joe’s destruction, become mouthpieces for the moralistic arguments of uplift advocates. “Here is another example,” they preached, “of the pernicious influence of the city on untrained [N]egroes. Is there no way to keep these people from rushing away from the small villages and country districts of the South up to the cities, where they cannot battle with the terrible force of a strange and unusual environment?” The gamblers continued to sermonize in their unlikely role as purveyors of the moral discourse of Darwinian determinism and social control, cynically abdicating responsibility for their exploitation of Joe. Through the parasitic gamblers, Dunbar unmasks conservative black opinion in its usual function articulating class-specific interests, and parodies denunciations of urban migration (one recalls that the Hamiltons were forced North by the Oakleys, and like many black migrants, had fled intolerable living conditions). Fearing that the migration northward would continue, the Banner Club regulars disingenuously concluded that “until the gods grew tired of their cruel sport, there must still be sacrifices to false ideals and unreal ambitions.” Spoken by disreputable men with few illusions, divine or otherwise, about their world, Dunbar’s title was a profoundly ironic euphemism for a network of exploitative social relations that was anything but God-given.

James Corrothers’s Literary Quest for Black Leadership

The black autobiographical tradition, dating back to the slave narratives, has often been synonymous with the freedom struggles of black Americans. By the Progressive Era, some black autobiographies not only embodied the collective goals of freedom, literacy, and Christian piety but also showed a relentlessly secular preoccupation with the success myth of the self-made man. In Booker T. Washington’s Up From Slavery, the Protestant work ethic and public achievement were central themes. Far less convincing in applying this type of formula was James D. Corrothers, who published his own autobiography, In Spite of the Handicap, in 1916.24

Corrothers’s autobiography was his solution to the racial constraints of the literary market that faced black writers of his time. In pursuit of white audiences and publication in the better paying magazines, Corrothers, like many others, tried to carve out, through Negro dialect, a narrow space for expression between the minstrel-derived representations of blacks in popular literature and journalism and the defensive response of those black writers and spokespersons who espoused the assimilationist, developmental ideology of racial uplift. Unlike Du Bois and most other advocates of uplift, however, Corrothers carried class stratification to divisive extremes. He used Negro dialect and minstrel images of other black men in his autobiography to validate his class authority and fitness for leadership. Instead of choosing the responsible path of racial uplift over minstrelsy, Corrothers’s autobiography often merged the two, as he employed minstrelsy to affirm himself as the embodiment of assimilation and race progress. As if to atone for his self-serving use of minstrelsy, and in the process suggesting the protean character of black identity at its most playful and uncategorizable, at rare moments in his autobiography—as he had done earlier in the irreverent The Black Cat Club—Corrothers refigured minstrelsy with sympathetic representations of urban black vernacular cultures. Both unique and representative, Corrothers’s works tell us a great deal about the intertwining of various versions of racist discourses in his day, specifically the largely unexamined minstrel nonsense residing within “respectable” race theories described by the ostensibly benign concept of assimilation.

Corrothers was a man of considerable energy and talent, a self-portrayal borne out by writings on race displaying the audacity of an escape artist. He was born in southern Michigan in 1869 in a community founded in the antebellum period by fugitive slaves, free blacks, and abolitionists. His mother died in childbirth, and he was raised by aunts and his paternal grandfather, a man of Scottish-Cherokee background who fought Indians. He attended the public schools there and recalled that “as the only colored boy in the village I had actually to thrash nearly every white boy in town before I was allowed to go to school in peace.” When his grandfather died, James supported himself by taking on a number of jobs, including work as a lumberjack, mill hand, waiter, amateur boxer, and coachman. An athletic and precocious youth, he worked in the sawmills of a Michigan town “full of rough men who loved . . . a fight.”25 Estranged from his father, Corrothers devoted himself to self-improvement, traveled throughout the region in search of work, and eventually reached Chicago in his late teens. There, he met the reformers Henry Demarest Lloyd and Frances Willard. With their assistance, Corrothers attended Northwestern University from 1890 to 1893. After a brief stint at Bennett College in North Carolina, Corrothers returned to Chicago, and, from a janitor’s job, he rose to become an occasional contributor to the Tribune. As a contributor to other newspapers, his work was often revised and published under the names of white authors. He was ordained a Methodist minister in 1894 and pastored churches in New York, New Jersey, Michigan, and Virginia. He lectured as an elocutionist and temperance advocate. Inspired by Dunbar’s success, he began to publish his own Negro dialect poems. For more than twenty-five years his poems, stories, and sketches appeared in leading newspapers and journals and in the black press. Fannie demons, his first wife, who bore him two sons, died in 1894. He married Rosina B. Harvey in 1906, and, at his death in 1917, he left her, their son Henry, and a surviving son from his first marriage.26

Although black writers generally used Negro dialect to figure the class and cultural differences that elite blacks insisted whites recognize, their use of dialect was not always a capitulation to racial stereotypes. Still, Corrothers’s assimilationist persona relied on dialect that went further into the forbidden terrain of minstrelsy than most other black writers dared. His autobiography thus pandered tacitly to distorted images of blacks and to the very prejudice the work bitterly denounced. Yet, reflecting the contradictory and ambiguous content of his writings, Corrothers at moments in the autobiography seemed to admit the limits of such a vision of assimilation, and located resistance in a black folk consciousness that masked its true intentions from more powerful whites. This work is unique in its blend of anger and accommodation, of aggression modulated by irreverent humor.

An examination of Corrothers’s writings, particularly the contrast between the assimilationist autobiography and the earlier Black Cat Club, with its urban setting and its use of black vernacular culture, marks Corrothers as bold, distinctive, and ambitious, if not foolhardy in his willingness to violate literary and aesthetic canons and exploit and subvert minstrelsy. Occurring when the urbanization of black communities created new audiences for black popular entertainments, Corrothers’s career also illustrates the complexities and contradictions within assimilation and racial uplift ideology. In the final analysis, Corrothers’s assimilationist writings were torn between an oppositional folk consciousness and a quest for individual success and authority articulated through strenuous masculinity. Corrothers’s self-construction remained subordinated to the paternalistic dictates of an exemplary, instrumental black leadership, loyal to the social order and the American nation.

Through uplift ideology, black spokespersons essentially accepted the prevailing view that “the race” was on trial against widespread negrophobic accusations of urban deviance and criminality. Yet at the same time, other blacks less burdened with the demand to be respectable were also manipulating and reclaiming minstrelsy and were exploring different modes of cultural expression in ragtime, blues, and Negro dialect literature and in the performances of barnstorming Negro vaudeville troupes.27 For his part, Corrothers seized upon assimilation as his greatest asset in an apparent bid for legitimacy as a black spokesman. He stressed his northern background, claiming that he had “never talked Negro dialect, nor done plantation antics.” And during his youth, he said, “My speech and ways were those of the white community about me.” To Corrothers, assimilation meant behaving like whites and avoiding those grotesque signs of blackness that one might see at a minstrel show.28

Washington’s success story, Up From Slavery, was Corrothers’s model. Like the Wizard of Tuskegee, he was not above telling a minstrel joke and passing off stereotypes as social truth. But Corrothers’s autobiography sought to turn his lack of success and his suffering into a sign of character and virtue. His career poignantly reveals (in a manner reminiscent of the more famous Dunbar) the burden of being an “authentic” black writer of Negro dialect, as genteel magazines such as Harper’s, Scribner’s, and Century often carried racial and ethnic stereotypes represented through dialect and illustrations. Since there was only enough room for one “poet of the race” in the eyes of the white public, Corrothers never achieved much more than scattered notice through his fiction writing. His solution was producing an autobiography that might reverse and redeem a lifetime of material hardship. In this work, and in two autobiographical short stories published just before it, Corrothers was anxious to identify himself with a strenuous but refined masculine authority and responsible black leadership. He believed that this strategy, aided by his fluency in Negro dialect, would gain him a sympathetic hearing from white readers.29

If Washington influenced Corrothers’s autobiography, it is just as likely that the success of minstrel comedians such as Bert Williams and Bob Cole provided a model for Corrothers’s earlier use of Negro humor in The Black Cat Club. Here, Negro humor represented an attempt to infuse minstrel forms with black content and resonances, purging minstrel narratives of white racism. The book was a collection of humorous, fictional sketches about a black Chicago literary society whose unlikely members were shady urban denizens still close to southern folk ways and ready to draw their razors at the slightest provocation. The club took its name from its mascot, a black cat that the members sometimes employed, in keeping with southern black folk belief, to intimidate superstitious persons deemed unfriendly to the society. His remorse over its appearance notwithstanding, Corrothers twice mentioned the volume in listing the achievements of his literary career, and was apparently proud that it “was published by a New York firm.”30

Black writers and audiences were divided on the merits of Negro dialect writing. Although many agreed with the view that “it can scarcely be believed . . . that great poetry can ever be clothed in the garb known as Negro dialect,”31 for others, Negro dialect symbolized an enduring black folk wisdom and provided a vehicle for articulating rage against past and present cruelties of enslavement and lynching. D. D. Bruce, in noting the widespread use of Negro dialect by black writers from about 1895 to 1906, asserts that instead of finding the form limiting, authors found it amenable to a variety of sentiments, including protest. Black writers employed dialect in work that appeared in such genteel periodicals consumed by blacks as the Colored American Magazine and Voice of the Negro.32 Clearly, Negro dialect was in some forms permissible to black editors and audiences and did not inherently entail minstrel stereotypes. But while The Black Cat Club trafficked in the usual stereotypes, its dialogue often a barrage of malaprop humor, the work also revealed minstrelsy to be a pliable sign whose meaning might diverge from the work of white imitators.

Its urban setting distinguished Corrothers’s dialect writing in The Black Cat Club from the plantation nostalgia that had brought success for white journalists Thomas Nelson Page, Joel Chandler Harris, Harry Stillwell Edwards, and a spate of other scribes of so-called Negro authenticity. Corrothers reveled in the image of the razor-wielding urban dandy, just comical enough to reassure whites’ subliminal fears at the implication of violence. He played upon such anxieties and put whiteness on the table for equal opportunity representation, as he sent the members of the club, razors at the ready, on a cultural exchange visit to a German saloon on the north side. Upon arrival, the threat of conflict was washed away in a torrent of beer, and Corrothers demonstrated his cultural ambidexterity with verses written in German dialect. At the same time, however, he seemed to criticize the popularity of dialect writing among a black middle class all too willing to celebrate public success and status in any guise. Corrothers’s hero, the president and poet laureate of the Black Cat literary society, Sandy Jenkins (a name familiar to readers of Frederick Douglass’s autobiography who remember the plantation conjurer whose powers the skeptical, assimilationist Douglass grudgingly acknowledged)33 is lionized among blacks in the novel for his diamond-accented fine dress as much as for his verse. Jenkins, who is also a gambler, regales a saloon crowd with his acknowledged masterpiece, “The Carving,” a mock-epic dialect poem about a razor duel over a light-complexioned black woman. Perhaps the transgressive implications of Corrothers’s view that black men like those in the Black Cat Club could exist freely outside the boundaries of law and respectability led him to end the book on a note of moral uplift with Jenkins’s marriage to a daughter of the black middle class, and his establishment of a catering business.34

The Black Cat Club’s carnivalistic conflation of black middle-class and vernacular cultures and its sympathy toward black migrants as heirs to a tradition of slave resistance satirized uplift’s, and the social order’s, repressive images of work and respectability. Men of the Black Cat Club boasted of their skill at avoiding exploitative work (“Ain’t nothin’ in it, no way!”). Sharing a laugh at their exploits as heroes of their own urban trickster tales, they duped political machines at election time and took bribes and patronage from corrupt white Democratic aldermen, while amongst themselves vehemently denouncing the Democratic Party as racist. Such tactics were, to Corrothers, merited by the racism of both political parties. Club members regarded such actions as guided by the “Chicago Golden Rule—”Do de other feller, befo’ he do you.’” Humor also masked a critique of Washington’s conservative philosophy; Sandy Jenkins, in the midst of a Bookerite tirade against “De Eddicated Cullud Man,” described an unlikely scenario that parodied economic self-help: “Now s’posin dey wuz a lynchin’ ”bout to take place, an’ de curly-headed brunette whut was to be de pahty acted upon hel’ a fust mo’gage on de home uv evah man in de lynching pahty. An’ s’posen mose o’ dem mo’-gages wuz ”bout due er ovah due; an’ s’posen jes’ ”foo’ dey lit de fiah er strung ”Im up, de cullud man wuz to say: ”Genamuns, ef you lynches me, ma son ’11 fo’close all ma mo’gages t’morrer! Dis am ma ultimatum!’ Do you thaink dey would have any lynchin’ ”at day? No sah! Now, whut could de college dahkey do?—Nothin’ but say his prayers.” Through Jenkins, Corrothers went on to damn Washington’s leadership with ostensible praise: “I tell you dat man’s doin’ a heap mo’ good in de Souf den all de graddiates whut’s a-slanderin’ uv ”Im an’ writin’ resolutions.” As proof, Jenkins dubiously urged his audience to “look at de genamus uv dis club! We ain’t got much book l’arnin’, but we has lit’a’ly cahved ouh way to fame an’ fortune.”35 Although the combination of dissent and the work’s minstrel trappings made this sort of thing sacrilegious to many, such humor created possibilities as a vehicle for protest from the margins, the lower frequencies, so to speak.

Corrothers’s portrayal of violent competition among blacks for status and prestige, mediated by farce in The Black Cat Club, was a theme that received far more serious and embittered treatment in his autobiography. In the later work, Corrothers also addressed the apparent contradiction between his professed commitment to assimilation and his past success as a dialect writer. Dialect in the autobiography served as racial raw material, fueling his quest for a higher style of writing, a quest that, among other factors, would confirm Corrothers’s fitness as a race leader. Even as he tried to dissociate himself from dialect and its stereotypes, he repeatedly used the form to strategic advantage by trying, as Washington had done, to construct a civilized leadership persona over the primitive, dialect-speaking “Old Negro.” But where Washington’s use of dialect exploited plantation stereotypes, for Corrothers, dialect was also a sign of a covert political consciousness that could resist whites. Just as the melodious sound of Negro spirituals enthralled abolitionists as their meaning masked internal codes of resistance, Corrothers, like Dunbar and the Du Bois of The Souls of Black Folk, were well aware that white audiences’ fascination with minstrelsy might be turned to blacks’ advantage. For his part, Corrothers used assimilationist minstrelsy to figuratively mask his actual blackness, and, in his autobiography, dialect enabled him, like whites who were quite free to do so on the stage, to figuratively don the mask. He could invoke the spectre and threat of unregenerate blackness and reassert his controlling presence at will in his narrative.36

Corrothers’s autobiography, a peculiar kind of success story, dwelled on the contradiction between uplift’s lofty civilizationist aspirations and the material struggles of black Americans. Corrothers laid bare what many elite and aspiring blacks were reluctant to speak of and preferred to submerge beneath respectable appearances: the painfully enormous gulf between literary and leadership aspirations and a lifetime of ill-paid, itinerant toil at an endless series of menial jobs and ministerial positions. Despite his poverty, he portrayed his ultimate “triumph” as his ability to profess faith in American society. This stance was convincing to Corrothers’s literary patron, journalist and editor Ray Stannard Baker, who noted in the introduction to the work that Corrothers’s book was “singularly without rancor” and that its author “in spite of difficulties has maintained a cheerful and helpful outlook toward life.” Baker seemed willing to ignore much of Corrothers’s anger in presenting him as an authentic black spokesman.37

Despite Baker’s disclaimer, Corrothers was not blind to the injustices of white society. Indeed, the lightness of his prose style allowed a considerable amount of anger, marking the autobiography as a bold venture. He noted that “the first mobbing of Negroes of which I ever heard did not occur in the South, but in Michigan,” in the town where he was raised. Suggesting the extent to which national ideals were contaminated by race hatred, Corrothers observed that the riot spoiled what was to have been a Fourth of July celebration. No one was killed, but “a number of coloured people were severely beaten and scarred for life.” Later, in Chicago, he vividly recalled how his ambitions as a journalist and poet clashed with the minstrel stereotypes promoted by the majority press. As a young reporter for the Chicago Tribune in the 1890s, Corrothers had the horrifying experience of seeing his piece on prominent Chicago blacks rewritten by a white editor in a demeaning dialect style. His promise to those he interviewed, including the eminent black surgeon Daniel Hale Williams, that they would be depicted favorably, compounded his humiliation when the insulting buffoonery reached print. Angrily protesting this incident, Corrothers was fired, and he latched onto work as a waiter at a lunch counter.38

Corrothers situated himself in the middle-class culture of progressive reform. In doing so he was hardly leaving the racial assumptions of minstrelsy behind. In an account of his first meeting with Frances Willard, Corrothers recalled swapping dialect jokes with the temperance and women’s rights advocate. As Willard joked at the expense of Irish Americans, Corrothers answered with the old, inside joke about the chronic lateness of blacks. Duly impressed, she offered him financial support toward his (incomplete) studies at Northwestern University. Corrothers recalled meeting Willard at an address he gave before the Women’s Christian Temperence Union while at Northwestern. Corrothers’s silence concerning how he came to become a temperance worker belies his coy assertion that he did not know “what on earth she came to hear me for.” Perhaps he was asserting his moral superiority by alluding to Dunbar’s alcoholism; in any case, such reticence downplayed his role as Willard’s protégé and defender in the wake of her controversial stand condoning lynching, and its crucial myth of the black rapist, a position that had elicited the wrath of another prominent Chicago reformer, Ida B. Wells.39

If Corrothers sought to popularize his fictive racial persona by manipulating the tension between assimilation and minstrelsy, far more overt, indeed exaggerated, was his emphasis on masculinity. This strategy was rooted in minstrelsy’s relentless attack on black manhood. Given the historical denial of the normative status of patriarchal protector to black men, advocates of racial uplift sought to escape this “feminized” image by asserting manliness as the epitome of rights and bourgeois respectability and as an antiracist panacea. In doing so, however, many black men internalized the myth that their perceived lack of manliness was a personal, moral failing, rather than a result of their historical and social condition. While the rhetoric of manhood rights was a staple of militant black protest, to many, manhood itself became synonymous with the progress of the race and thus extended its mission of social control to the lives and sexuality of black women in the name of protection. For Corrothers, however, black women were virtually invisible in his appropriation of the popular literary conventions of white working-class manliness, as seen in his frequent references to fistic duels, boxing, and to his own athletic prowess and capacity for heavy physical labor. Indeed, Corrothers sought at some level to incorporate blackness and white manliness in the same strenuous male body. If working-class white men built their identity on distorted minstrel images of black males, Corrothers felt entitled to construct his autobiographical persona through an appropriation of the blackness of white masculinity.

Corrothers’s self-proclaimed superiority and “goodness” depended heavily on his accounts of physical combat with dangerous, razor-toting black men textually signaled by the Negro dialect he had them speak. Such roguish stereotypes served as foils for his bourgeois aspirations to self-improvement as a poet and minister, as Corrothers stressed the dignity of labor and the work ethic and portrayed himself as a paragon of tough, if refined and chaste, manliness. Revelling in his physique, Corrothers noted that he personally brought an athletic program and “physical culture” to Bennett College, where “the teacher of physiology invited me to pose in sleeveless boxing costume before her class, that they might, as she expressed it, ”observe the development and play of the muscles.’”40 Careful to avoid the implication of overt sexuality in such displays, Corrothers professed to be “a novice at Cupid’s game.” However idiosyncratic, Corrothers’s depictions of his chaste, aestheticized body clearly fit the pattern of uplift’s attempts to establish fraternal, as well as middle-class, solidarity across racial lines with white males and reflected his literary quest to portray respectable black manhood. His emphasis on masculinity was solidly in the tradition, within racial uplift ideology, of defining “the race” as a masculine collectivity, a construction partly explained by black male writers’ anxiety over the harsh realities of the sexual exploitation of black women by white men.41

Repeatedly, Corrothers took an antagonistic stance in his autobiography toward the image of those blacks he viewed as the antithesis of the assimilationist ideals of uplift. Even as he denounced Jim Crow railroad cars for their failure to respect the claims of middle-class black women to protected femininity, he insisted that “white people . . . are not entirely to blame for the bringing about of these conditions in the South.” Instead, he saw “rowdy Negroes . . . [and] disgusting and dangerous displays of black savagery” as spoiling things for “decent and intelligent coloured people.”42 Surpassing the uplift strategy of insisting on a distinction between “better” and “undeveloped” classes of blacks and following the pattern of Washington’s autobiographical attempts to discredit rival black leaders, Corrothers represented most other black men, leaders and masses, as his enemy. In this, he epitomized the individualistic psychology of oppressed minorities for whom nothing could be more foreign, or undesirable, than a collective consciousness. Of course, the American context for messianic notions of black leadership (“the Moses of his race”) and uplift ideology’s vanguardist assumptions did little to discourage this way of thinking. Be that as it may, Corrothers portrayed himself as the victim of scandals and disputes, engineered by his cultural inferiors, which cost him ministerial positions. Indeed, he served in three denominations, African Methodist Episcopal, Baptist, and finally, Presbyterian.

Just as humor, as a self-conscious narrative strategy, might channel anger, so did his eruptions of anger, when directed against black rivals, real and imagined, contain a measure of insight. Uplift declarations of race solidarity masked a brutal individualism. Corrothers made the painful realization that black institutions were so marginal that control over their limited resources was necessarily a competitive endeavor. With so few professional and leadership opportunities to go around, leadership was primarily a matter of dominance. He knew that black men like himself wielded such power and influence as they were able to obtain in fierce, often covert competition with their would-be allies. Repeatedly, he complained of black congregations unable to pay his salary, and he claimed to have staffed, practically singlehandedly, a black newspaper in Chicago, which could not pay him much before it failed. Painfully aware that “my race could not employ me,” Corrothers wrote gratefully of the assistance he had received over the years from whites.43

Yet there was something more complicated about Corrothers’s quest for vindication as a truly representative black leader. As if to reflect his many reversals of fortune and to recall the mischief of The Black Cat Club, his narrative contains moments that dislodge assimilation as a privileged strategy. On the one hand, recalling his days at Bennett College, he disdainfully described southern black college presidents as “so many . . . ignorant frauds” and carped on the “Negro mannerisms” of a Greek and Sanskrit professor who “invariably said ”dis’ and ”dat’ and mispronounced a number of common words.” Yet later, he was surprised to discover that this same professor of the “infelicitous speech” was capable of a rousing and eloquent address protesting Jim Crow.44

Here and elsewhere, in a manner that recalled The Black Cat Club, Corrothers suggested that to be unassimilated meant an inclination to resist and challenge, however indirectly, white supremacy. He described being rescued from a confrontation on a Jim Crow car by a dialect-speaking Pullman porter and recalled with approval the cunning of a “half-savage” African prince who successfully defrauded white colonial investors. “From the viewpoint of the prince,” Corrothers remarked, “it had been a game of wits.” Here Corrothers suggested that the moral bankruptcy of colonialism justified turning the shears against those wolves willing to take up the white man’s burden. Given the vulnerability of blacks to this sort of exploitation, success for a black man, following the Chicago golden rule, could be as much an amoral, duplicitous con game as it was a matter of meritorious assimilation.45

In one crucial instance, he saw his own assimilation as a liability. As a minister, he often regretted his “lack of early contact with the masses of my race.” Finding himself at a disadvantage in discerning “their moods and methods of thought,” he noted that “the unschooled Negro, when he premeditates church meannesses, either talks in riddles or assumes a sullen, enigmatic manner quite difficult for me to fathom.” Immediately, in the next breath, Corrothers rendered the folksy dialect voice of the black preacher: “Often, I have envied,” he wrote, “the reassuring confidence of the old plantation preacher” who warned his new congregation, “Chilluns, you cain’t fool me; ”ca’se I has good, bo’n undahstan’in o’ mah people: When a niggah sneeze, I knows whah he cotch his col”. His sense of alienation made it difficult for him to compete with the folk preacher’s ability to enthrall his congregation. Wishing he could “get over” on his congregations before they could send him packing, Corrothers’s resentment communicated his own thwarted desire for mastery and control over other blacks.46

Corrothers sought power and legitimation outside the black community, compromising the antiracist aspects of his narrative. The construction of an authoritative black public persona paradoxically necessitated cleansing himself of the stigma of racial difference. Here is his recollection of a stint working with a group of black workingmen on a freight boat over the Great Lakes: “They were of the ”razor-toting’ class. . . . Their ways were not my ways. . . . Their conversations fairly reeked with lasciviousness and vulgarity. They were not Northern Negroes, but Southern Negroes, come North and gone to the devil. The first night of my association with these men I was speechless with the horror of it. I thought I had almost reached the confines of hell. . . . Before the end of my second trip, I had thrashed the bully of the boat in a combat which came near ending fatally for me.”47 More than once in his autobiography, he represented his quest for supremacy among blacks as a violent struggle among black male rivals, enacted before a judging white readership. Zealously guarding his own image, lest he be mistaken for one of those boat hands, Corrothers noted that he abhorred liquor, found dancing “a silly waste of time,” and followed inner promptings to keep his life clean and decent. His account of the dangerous black boathands was in marked contrast to the nostalgic remembrance of those white lumberjacks with whom he had grown up “rough and unafraid . . . thoroughly at home in [the] rough company” of men who loved strong drink and fighting.48

By his own account, ability, spotless character, and refined speech were apparently insufficient in themselves. For Corrothers, self-improvement and leadership meant a willingness to fight and subdue other blacks, though he suggested in one instance that white manipulation lay behind violence among blacks. Corrothers recalled that during his young manhood, he fought into submission what he called “a big Negro of the lumbering fieldhand type” whom an angry white former boss had set upon him. Lest (white) readers feel threatened by all the fighting, Corrothers assured them that he lacked a “blood lust” for fighting: “My youthful fistic encounters were experiences which have seemed to me like reassuring milestones on my road to higher achievements and development. Because of them I have said to myself: ”I can do this other, better, nobler thing!’ They have given me courage, often, to fight on against odds.”49 Violence was central to his narrative of self-improvement, despite Corrothers’s attempt to portray his development as something more benign.

Professing shame for The Black Cat Club and much of his earlier dialect verse, he aspired to what he viewed as a higher style of writing, modeled after Swinburne, which became the object of his prodigious work ethic and his quest for self-improvement. At last, he recalled: “I was working for my race, as well as for myself and my family. . . . I was doing a higher class of work than I had ever done before. . . . I felt that I had mastered Negro dialect; but I was far from having mastered the art of expressing worthy thoughts in literary English. Besides, I moved in an element of society which, for the most part, did not use good English.”50 Such statements, presumably reconciling personal ambition with rhetorical concerns for the race’s welfare, failed to do justice to Corrothers’s literary achievements. Middle-class aspirations led him in his autobiography to defer to assimilationist cultural standards for his writing. Corrothers’s literary ambitions suggested the anxiety of the American artist in relation to Europe, as well as the torn, contradictory identities produced by writing for both black and white audiences. The fact remained, however, that his poems, like the work of most black writers, advanced political priorities and black formal alternatives that often rendered such imitative aesthetic considerations less significant. The Victorian stoicism and forebearance of the protest poems (which would soon find their apotheosis in Claude McKay’s “If We Must Die,” penned to protest racial violence in 1919) Corrothers published in W. E. B. Du Bois’s Crisis found their formal opposite in the dialect poems he published in the Century Magazine at the same time. As with The Black Cat Club, humorous dialect verse voiced protests belied by his ambition to express “worthy thoughts in literary English.”

In “An Indignation Dinner,” Corrothers couches a demand for redistributive justice for blacks in dialect verse. The poem’s speaker tells of “a secret meetin’, whah de / white folks could n’t hear” over how to ensure a good Christmas dinner in the face of hard times. However softened by humor, the poem depicts an angry group consciousness. At the meeting, one man points out that “de white folks is a-tryin’ to keep us down,” and that “dey’s bought us, sold us, beat us; / now dey ”buse us ca’se we’s free.” Facing the holiday indignant, poor, and desperate from low wages, the bounteous livestock and crops “on a certain genmun’s fahm” spurs the group to form “a committee foh to vote de goodies here.” Speaking significantly in the first-person plural voice, the poem’s narrator describes the festive, capacious Christmas dinner enjoyed by the group, “Not beca’se we was dishonest, but indignant, sah. Dat’s all.” As in The Black Cat Club, a sense of injustice animates blacks’ seizure of whites’ property, and challenges stereotypes of chicken stealing and criminality.51

The political content of such dialect works found a counterpart in even a standard English work like “In the Matter of Two Men,” published in the Crisis in 1915. The poem’s protest rehearses the exaltation of manly physical prowess in his autobiography. In the poem, Corrothers posits a Darwinian teleology created by slavery and Jim Crow in which whites would lose vitality and blacks would become a masterly race:

Though the white storm howls, or the sun is hot,

The black must serve the white.

And it’s, oh, for the white man’s softening flesh,

While the black man’s muscles grow!

Well, I know which grows the mightier,

I know; full well I know.

Here evolutionary theory is thus pressed to the service of upsetting the social order, revising dogmas of developmental tutelage and uplift:

Ingenious grows the humbler race

In oppression’s prodding school.

And it’s oh, for a white man gone to seed,

While the Negro struggles so!

And I know which race develops most, I know; yes, well I know.

The accommodations of his autobiography are absent here, as Corrothers exposes the racist double standard used to discredit black political aspirations.

The white man votes for his color’s sake,

While the black, for his is barred;

(Though “ignorance” is the charge they make),

But the black man studies hard.

Reviving the old antislavery argument that southern society had regressed to a backward condition as whites had grown feeble, lazy, and immoral by enslaving blacks, Corrothers concluded: “So, I know which man must win at last, / I know! Ah, Friend, I know!” Corrothers seemed to fuse evolutionary theory with Christian teleology, as in his autobiography, where his elaborate descriptions of hard menial labor evoked the suffering of the stations of the cross. Unloading cargoes of salt and flour from freight barges, Corrothers described working without food or rest “for forty-eight and fifty-two hours at a stretch.” Handling heavy, dripping barrels of wet salt, Corrothers wrote “my hands would crack open and drip blood. But I stuck it out.”52

Corrothers’s autobiographical theme of the betrayal of his leadership by irresponsible, unassimilated blacks was central to his 1914 short story “At the End of the Controversy.” Its protagonist, Grant Noble, a black minister in New England, had successfully defended the black community from a prominent white minister’s public accusations of vote-selling and criminality. Having prevailed against one adversary, Noble, “broad-shouldered, erect, . . . a personality to be reckoned with, a man among men,” met his match in a conspiracy among members of his congregation seeking to defraud white philanthropists on the pretext of rebuilding the church. “The plan now was to use the popularity of the pastor to make a ”killing’ from the whites,” Corrothers wrote, representing the conspirators—“a certain brand of negroes”—with dialect: “”we will ast de pastah to do mose o’ de solicitin’,’ said Conspirator No. 1.” When Noble, a man of integrity (who had excelled at varsity football in college), refused to take part, the angry conspirators ousted him from the church despite the fatal illness of his wife and one of his two sons. “For doing right, he was exploded forth into the great army of the unemployed.” The story was accompanied by illustrations, including one depicting the pastor’s departure amidst a throng of grotesque Negro stereotypes: “And straight through the crowd he went; overblowing this spawn of savagery with an awing look he passed out and was gone.” Corrothers’s story ultimately affirmed the accusations that the exemplary Noble had refuted, as his omniscient narrator confessed that Noble’s flock had actually been engaged in political corruption all along.53

While “At the End of the Controversy” laid the groundwork for the later autobiography’s attempt to portray Corrothers as a natural aristocrat exiled by resentful black ministers, a story that appeared in the NAACP organ Crisis in 1913, “A Man They Didn’t Know” situated the problems of black leadership within global affairs by imagining a military alliance of Japan and Mexico against the United States, further supported by black deserters from the U.S. Army and the secession of Hawaii, led by angry Japanese Americans.