Chapter 11. Inheritance and Polymorphism

In Chapter 7, you learned

how to create new types by declaring classes, and in Chapter 6, you saw a discussion of the

principle object relationships of association, aggregation, and

specialization . This chapter focuses on

specialization, which is implemented in C# through

inheritance . This chapter also explains how instances of more

specialized classes can be treated as if they were instances of more

general classes, a process known as polymorphism

. This chapter ends with a consideration of

sealed classes, which cannot be specialized, and a

discussion of the root of all classes, the Object class.

Specialization and Generalization

Classes and their instances (objects) do not exist in a vacuum, but rather in a network of interdependencies and relationships, just as we, as social animals, live in a world of relationships and categories.

One of the most important relationships among objects in the real world is specialization, which can be described as the is-a relationship. When we say that a dog is a mammal, we mean that the dog is a specialized kind of mammal. It has all the characteristics of any mammal (it bears live young, nurses with milk, has hair), but it specializes these characteristics to the familiar characteristics of canis domesticus. A cat is also a mammal. As such, we expect it to share certain characteristics with the dog that are generalized in Mammal, but to differ in those characteristics that are specialized in cats.

The specialization and generalization relationships are both reciprocal and hierarchical. Specialization is just the other side of the generalization coin: Mammal generalizes what is common between dogs and cats, and dogs and cats specialize mammals to their own specific subtypes.

These relationships are hierarchical because they create a relationship tree, with specialized types branching off from more generalized types. As you move “up” the hierarchy, you achieve greater generalization. You move up toward Mammal to generalize that dogs, cats, and horses all bear live young. As you move “down” the hierarchy you specialize. Thus, the cat specializes Mammal in having claws (a characteristic) and purring (a behavior).

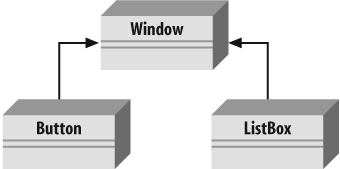

Similarly, when you say that ListBox and Button are Windows, you

indicate that there are characteristics and behaviors of Windows that

you expect to find in both of these types. In other words, Window

generalizes the shared characteristics of both ListBox and Button, while each specializes its own

particular characteristics and behaviors.

The Unified Modeling Language (UML) is a standardized language for describing an object-oriented system. The UML has many different visual representations, but in this case, all you need to know is that classes are represented as boxes. The name of the class appears at the top of the box, and (optionally) methods and members can be listed in the sections within the box.

In the UML, you model specialization relationships, as shown in

Figure 11-1. Note that

the arrow points from the more specialized class up to the more general

class. In the figure, the more specialized Button and ListBox classes point up to the more general

Window class.

It is not uncommon for two classes to share functionality. When this occurs, you can factor out these commonalities into a shared base class, which is more general than the specialized classes. This provides you with greater reuse of common code and gives you code that is easier to maintain, because the changes are located in a single class rather than scattered among numerous classes.

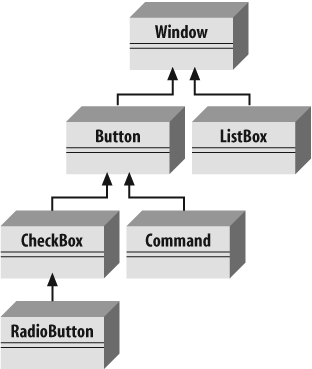

For example, suppose you started out creating a series of objects,

as illustrated in Figure

11-2. After working with RadioButtons, CheckBoxes, and Command

buttons for a while, you realize that they share certain characteristics

and behaviors that are more specialized than Window, but more general

than any of the three. You might factor these common traits and

behaviors into a common base class, Button, and rearrange your inheritance

hierarchy, as shown in Figure

11-3. This is an example of how generalization is used in

object-oriented development.

The UML diagram in Figure 11-3 depicts the

relationship among the factored classes and shows that both ListBox and Button derive from Window, and that Button is specialized into CheckBox and

Command. Finally, RadioButton derives from CheckBox. You can thus say

that RadioButton is a CheckBox, which in turn is a Button, and that Buttons are Windows.

This is not the only, or even necessarily the best, organization for these objects , but it is a reasonable starting point for understanding how these types (classes) relate to one another.

Tip

Actually, although this discussion might reflect how some widget hierarchies are organized, I am very skeptical of any system in which the model does not reflect how I perceive reality, and when I find myself saying that a RadioButton is a CheckBox, I have to think long and hard about whether that makes sense. I suppose a RadioButton is a kind of CheckBox. It is a checkbox that supports the idiom of mutually exclusive choices. That said, it is a bit of a stretch and might be a sign of a shaky design.

Inheritance

In C#, the specialization relationship is implemented using a principle called inheritance . This is not the only way to implement specialization, but it is the most common and most natural way to implement this relationship.

Saying that ListBox inherits

from (or derives from) Window

indicates that it specializes Window.

Window is referred to as the

base class, and ListBox is

referred to as the derived class. That is, ListBox derives its characteristics and

behaviors from Window and then specializes to its own particular

needs.

Tip

You’ll often see the immediate base class referred to as the

parent class, and the derived class referred to as the

child class, while the top-most class, Object, is called the

root class.

Implementing Inheritance

In C#, you create a derived class by adding a colon after the name of the derived class, followed by the name of the base class:

public class ListBox : Window

This code declares a new class, ListBox, that derives from Window. You can read the colon as “derives

from.”

The derived class inherits all the members of the base class

(both member variables and methods), and methods of the derived class

have access to all the public and protected members of the base class.

The derived class is free to implement its own version of a base class

method. This is called hiding the

base class method and is accomplished by marking the method with the

keyword new. (Many C# programmers

advise never hiding base class methods as it is unreliable, hard to

maintain, and confusing.)

Tip

This is a different use of the keyword new than you’ve seen earlier in this book.

In Chapter 7, new was used to create an object on the

heap; here, new is used to

replace the base class method. Programmers say the keyword new is overloaded, which means that the

word has more than one meaning or use.

The new keyword indicates

that the derived class has intentionally hidden and replaced the base

class method, as shown in the Example 11-1. (The new keyword is also discussed in the section

"Versioning with new and

override,” later in this chapter.)

using System;

public class Window

{

// constructor takes two integers to

// fix location on the console

public Window( int top, int left )

{

this.top = top;

this.left = left;

}

// simulates drawing the window

public void DrawWindow( )

{

Console.WriteLine( "Drawing Window at {0}, {1}",

top, left );

}

// these members are private and thus invisible

// to derived class methods; we'll examine this

// later in the chapter

private int top;

private int left;

}

// ListBox derives from Window

public class ListBox : Window

{

// constructor adds a parameter

public ListBox( int top, int left, string theContents ) :

base( top, left ) // call base constructor

{

mListBoxContents = theContents;

}

// a new version (note keyword) because in the

// derived method we change the behavior

public new void DrawWindow( )

{

base.DrawWindow( ); // invoke the base method

Console.WriteLine( "Writing string to the listbox: {0}",

mListBoxContents );

}

private string mListBoxContents; // new member variable

}

public class Tester

{

public static void Main( )

{

// create a base instance

Window w = new Window( 5, 10 );

w.DrawWindow( );

// create a derived instance

ListBox lb = new ListBox( 20, 30, "Hello world" );

lb.DrawWindow( );

}

}The output looks like this:

Drawing Window at 5, 10

Drawing Window at 20, 30

Writing string to the listbox: Hello worldExample 11-1

starts with the declaration of the base class Window. This class implements a constructor

and a simple DrawWindow( ) method.

There are two private member variables, top and left. The program is analyzed in detail in

the following sections.

Calling Base Class Constructors

In Example

11-1, the new class ListBox

derives from Window and has its own

constructor, which takes three parameters. The ListBox constructor invokes the constructor

of its parent by placing a colon (:) after the parameter list and then

invoking the base class constructor with the keyword base:

public ListBox( int theTop, int theLeft, string theContents):base(theTop, theLeft) // call base constructorBecause classes cannot inherit constructors, a derived class must implement its own constructor and can only make use of the constructor of its base class by calling it explicitly.

If the base class has an accessible default constructor, the

derived constructor is not required to invoke the base constructor

explicitly; instead, the default constructor is called implicitly as

the object is constructed. However, if the base class does

not have a default constructor, every derived

constructor must explicitly invoke one of the

base class constructors using the base keyword. The keyword base identifies the base class for the

current object.

Tip

As discussed in Chapter 7, if you do not declare a constructor of any kind, the compiler creates a default constructor for you. Whether you write it yourself or you use the one provided by the compiler, a default constructor is one that takes no parameters. Note, however, that once you do create a constructor of any kind (with or without parameters), the compiler does not create a default constructor for you.

Controlling Access

You can restrict the visibility of a class and its

members through the use of access modifiers , such as public,

private, and protected . (See Chapter

8 for a discussion of access modifiers.)

As you’ve seen, public allows

a member to be accessed by the member methods of other classes, while

private indicates that the member

is visible only to member methods of its own class. The protected keyword extends visibility to

methods of derived classes.

Classes, as well as their members, can be designated with any of

these accessibility levels. If a class member has a different access

designation than the class, the more restricted access applies. Thus,

if you define a class, myClass, as

follows:

public class MyClass

{

// ...

protected int myValue;

}the accessibility for myValue

is protected even though the class itself is public. A public class is

one that is visible to any other class that wishes to interact with

it. If you create a new class, myOtherClass, that derives from myClass, like this:

public class MyClass : MyOtherClass

{

Console.WriteLine("myInt: {0}", myValue);

}MyOtherClass can access

myValue, because MyOtherClass derives from MyClass, and myValue is protected. Any class that doesn’t

derive from MyClass would not be

able to access myValue.

Polymorphism

There are two powerful aspects to inheritance. One is code reuse.

When you create a ListBox class,

you’re able to reuse some of the logic in the base (Window)

class.

What is arguably more powerful, however, is the second aspect of inheritance: polymorphism . Poly means many and morph means form. Thus, polymorphism refers to being able to use many forms of a type without regard to the details.

When the phone company sends your phone a ring signal, it does not know what type of phone is on the other end of the line. You might have an old-fashioned Western Electric phone that energizes a motor to ring a bell, or you might have an electronic phone that plays digital music.

As far as the phone company is concerned, it knows only about the “base type” phone and expects that any “derived” instance of this type knows how to ring. When the phone company tells your phone to ring, it, effectively, calls your phone’s ring method, and old fashioned phones ring, digital phones trill, and cutting-edge phones announce your name. The phone company doesn’t know or care what your individual phone does; it treats your telephone polymorphically.

Creating Polymorphic Types

Because a ListBox

is a Window

and a Button is

a Window, you expect to

be able to use either of these types in situations that call for a

Window. For example, a form might want to keep a collection of all the

derived instances of Window it manages (buttons, lists, and so on), so

that when the form is opened, it can tell each of its Windows to draw

itself. For this operation, the form does not want to know which

elements are ListBoxes and which

are Buttons; it just wants to tick

through its collection and tell each one to “draw.” In short, the form

wants to treat all its Window objects polymorphically.

You implement polymorphism in two steps:

Create a base class with virtual methods.

Create derived classes that override the behavior of the base class’s virtual methods.

To create a method in a base class that supports polymorphism,

mark the method as virtual. For

example, to indicate that the method DrawWindow( ) of class Window in Example 11-1 is polymorphic,

add the keyword virtual to its

declaration, as follows:

publicvirtual void DrawWindow( )Each derived class is free to inherit and use the base class’s

DrawWindow( ) method as is or to

implement its own version of DrawWindow( ). If a derived class does override the DrawWindow( ) method, that overridden

version will be invoked for each instance of the derived class. You

override the base class virtual method by using the keyword override in the derived class method

definition, and then add the modified code for that overridden

method.

Example 11-2 shows how to override virtual methods .

using System;

public class Window

{

// constructor takes two integers to

// fix location on the console

public Window( int top, int left )

{

this.top = top;

this.left = left;

}

// simulates drawing the window

publicvirtual void DrawWindow( )

{

Console.WriteLine( "Window: drawing Window at {0}, {1}",

top, left );

}

// these members are protected and thus visible

// to derived class methods. We'll examine this

// later in the chapter. (Typically, these would be private

// and wrapped in protected properties, but the current approach

// keeps the example simpler.)

protected int top;

protected int left;

} // end Window

// ListBox derives from Window

public class ListBox : Window

{

// constructor adds a parameter

// and calls the base constructor

public ListBox(

int top,

int left,

string contents ) : base( top, left )

{

listBoxContents = contents;

}

// an overridden version (note keyword) because in the

// derived method we change the behavior

public override void DrawWindow( )

{

base.DrawWindow( ); // invoke the base method

Console.WriteLine( "Writing string to the listbox: {0}",

listBoxContents );

}

private string listBoxContents; // new member variable

} // end ListBox

public class Button : Window

{

public Button(

int top,

int left ) : base( top, left )

{}

// an overridden version (note keyword) because in the

// derived method we change the behavior

public override void DrawWindow( )

{

Console.WriteLine( "Drawing a button at {0}, {1}\n",

top, left );

}

} // end Button

public class Tester

{

static void Main( )

{

Window win = new Window( 1, 2 );

ListBox lb = new ListBox( 3, 4, "Stand alone list box" );

Button b = new Button( 5, 6 );

win.DrawWindow( );

lb.DrawWindow( );

b.DrawWindow( );

Window[] winArray = new Window[3];

winArray[0] = new Window( 1, 2 );

winArray[1] = new ListBox( 3, 4, "List box in array" );

winArray[2] = new Button( 5, 6 );

for ( int i = 0; i < 3; i++ )

{

winArray[i].DrawWindow( );

} // end for

} // end Main

} // end TesterThe output looks like this:

Window: drawing Window at 1, 2

Window: drawing Window at 3, 4

Writing string to the listbox: Stand alone list box

Drawing a button at 5, 6

Window: drawing Window at 1, 2

Window: drawing Window at 3, 4

Writing string to the listbox: List box in array

Drawing a button at 5, 6In Example 11-2,

ListBox derives from Window and

implements its own version of DrawWindow( ):

publicoverride void DrawWindow( )

{

base.DrawWindow( ); // invoke the base method

Console.WriteLine ("Writing string to the listbox: {0}",

listBoxContents);

}The keyword override tells

the compiler that this class has intentionally overridden how DrawWindow( ) works. Similarly, you’ll

override DrawWindow( ) in another

class that derives from Window: the

Button class.

In the body of the example, you create three objects: a Window, a ListBox, and a Button. Then you call DrawWindow( ) on each:

Window win = new Window(1,2);

ListBox lb = new ListBox(3,4,"Stand alone list box");

Button b = new Button(5,6);

win.DrawWindow( );

lb.DrawWindow( );

b.DrawWindow( );This works much as you might expect. The correct DrawWindow( ) method is called for each. So

far, nothing polymorphic has been done (after

all, you called the Button version

of DrawWindow on a Button object). The real magic starts when

you create an array of Window

objects.

Because a ListBox

is a Window, you are free to place a ListBox into an array of Windows. Similarly, you can add a Button to a collection of Windows, because a Button is a Window.

Window[] winArray = new Window[3];

winArray[0] = new Window(1,2);

winArray[1] = new ListBox(3,4,"List box in array");

winArray[2] = new Button(5,6);The first line of code declares an array named winArray that will hold three Window objects. The next three lines add new

Window objects to the array. The

first adds an object of type Window. The second adds an object of type

ListBox (which is a Window because ListBox derives from Window), and the third adds an object of

type Button, which is also a type

of Window.

What happens when you call DrawWindow( ) on each of these objects?

for (int i = 0; i < winArray.Length-1; i++)

{

winArray[i].DrawWindow();

}This code uses i as a counter

variable. It calls DrawWindow( ) on

each element in the array in turn. The value i is evaluated each time through the loop,

and that value is used as an index into the array.

All the compiler knows is that it has three Window objects and that you’ve called

DrawWindow( ) on each. If you had

not marked DrawWindow( ) as

virtual, Window’s original DrawWindow( ) method would be called three

times.

However, because you did mark DrawWindow( ) as virtual, and because the

derived classes override that method, when you call DrawWindow( ) on the array, the right thing

happens for each object in the array. Specifically, the compiler

determines the runtime type of the actual objects (a Window, a ListBox, and a Button) and calls the right method on each.

This is the essence of polymorphism.

Tip

The runtime type of an object is the actual (derived) type. At

compile time, you do not have to decide what kind of objects will be

added to your collection, so long as they all derive from the

declared type (in this case, Window). At runtime, the actual type is

discovered and the right method is called. This allows you to pick

the actual type of objects to add to the collection while the

program is running.

Note that throughout this example, the overridden methods are

marked with the keyword override:

public override void DrawWindow( )

The compiler now knows to use the overridden method when

treating these objects polymorphically. The compiler is responsible

for tracking the real type of the object and for handling the late

binding, so that ListBox.DrawWindow( ) is called when the Window reference really points to a

ListBox object.

Versioning with new and override

In C#, the programmer’s decision to override a virtual

method is made explicit with the override keyword. This helps you release new

versions of your code; changes to the base class will not break

existing code in the derived classes. The requirement to use the

override keyword helps prevent that

problem.

Here’s how: assume for a moment that Company A wrote the

Window base class in Example 11-2. Suppose also

that the ListBox and RadioButton classes were written by

programmers from Company B using a purchased copy of the Company A

Window class as a base. The programmers in Company B have little or no

control over the design of the Window class, including future changes

that Company A might choose to make.

Now suppose that one of the programmers for Company B decides to

add a Sort( ) method to ListBox:

public class ListBox : Window

{

public virtual void Sort( ) {...}

}This presents no problems until Company A, the author of

Window, releases Version 2 of its

Window class, and the programmers

in Company A also add a Sort( )

method to their public class Window:

public class Window

{

// ...

public virtual void Sort( ) {...}

}In other object-oriented languages (such as C++), the new

virtual Sort( ) method in Window would now act as a base virtual

method for the Sort( ) method in

ListBox, which is not what the

developer of ListBox

intended.

C# prevents this confusion. In C#, a virtual function is always considered to be

the root of virtual dispatch ; that is, once C# finds a virtual method,

it looks no further up the inheritance hierarchy. If a new virtual

Sort( ) function is introduced into

Window, the runtime behavior of

ListBox is unchanged.

When ListBox is compiled

again, however, the compiler generates a

warning:

...\class1.cs(54,24): warning CS0114: 'ListBox.Sort( )' hides

inherited member 'Window.Sort( )'.

To make the current member override that implementation,

add the override keyword. Otherwise add the new keyword.Warning

Never ignore warnings. Treat them as errors until you have satisfied yourself that you understand the warning and that it is not only innocuous but that there is nothing you can do to eliminate the warning. Your goal, (almost) always, is to compile warning-free code.

To remove the warning, the programmer must indicate what she

intends.[8] She can mark the ListBox Sort( ) method new to indicate

that it is not an override of the virtual method

in Window:

public class ListBox : Window

{

public new virtual void Sort( ) {...}This action removes the warning. If, on the other hand, the

programmer does want to override the method in Window, she need only

use the override keyword to make

that intention explicit:

public class ListBox : Window

{

public override void Sort( ) {...}Warning

To avoid this warning, it might be tempting to add the

new keyword to all your virtual

methods. This is a bad idea. When new appears in the code, it ought to

document the versioning of code. It points a potential client to the

base class to see what it is that you are intentionally not

overriding. Using new scattershot

undermines this documentation and reduces the utility of a warning

that exists to help identify a real issue.

If the programmer now creates any new classes that derive from

ListBox, those derived classes will

inherit the Sort( ) method from

ListBox, not from the base Window class.

Abstract Classes

Each type of Window has

a different shape and appearance. Drop-down listboxes look very

different from buttons. Clearly, every subclass of Window

should implement its own DrawWindow( ) method—but so far, nothing in

the Window class enforces that they must do so. To require subclasses to

implement a method of their base, you need to designate that method as

abstract .

An abstract method has no implementation. It creates a method name and signature that must be implemented in all derived classes. Furthermore, making at least one method of any class abstract has the side effect of making the class abstract.

Abstract classes establish a base for derived classes, but it is not legal to instantiate an object of an abstract class. Once you declare a method to be abstract, you prohibit the creation of any instances of that class.

Thus, if you were to designate DrawWindow( ) as an abstract method in the

Window class, the Window class itself would become abstract.

Then you could derive from Window,

but you could not create any Window

instances. If the Window class is an

abstraction, there is no such thing as a simple Window object, only objects derived from

Window.

Making Window.DrawWindow( )

abstract means that each class derived from Window would have to implement its own

DrawWindow( ) method. If the derived

class failed to implement the abstract method, that derived class would

also be abstract, and again no instances would be possible.

Designating a method as abstract is accomplished by placing the

abstract keyword at the beginning of

the method definition:

abstract public void DrawWindow( );

(Because the method can have no implementation, there are no braces, only a semicolon.)

If one or more methods are abstract, the class definition must

also be marked abstract, as in the

following:

abstract public class Window

Example 11-3

illustrates the creation of an abstract Window class and an abstract

DrawWindow( ) method.

using System; publicabstractclass Window { // constructor takes two integers to // fix location on the console public Window( int top, int left ) { this.top = top; this.left = left; } // simulates drawing the window // notice: no implementation publicabstractvoid DrawWindow( ); protected int top; protected int left; } // end class Window // ListBox derives from Window public class ListBox : Window { // constructor adds a parameter public ListBox( int top, int left, string contents ) : base( top, left ) // call base constructor { listBoxContents = contents; } // an overridden version implementing the // abstract method publicoverride void DrawWindow( ) { Console.WriteLine( "Writing string to the listbox: {0}", listBoxContents ); } private string listBoxContents; // new member variable } // end class ListBox public class Button : Window { public Button( int top, int left ) : base( top, left ) { } // implement the abstract method publicoverride void DrawWindow( ) { Console.WriteLine( "Drawing a button at {0}, {1}\n", top, left ); } } // end class Button public class Tester { static void Main( ) { Window[] winArray = new Window[3]; winArray[0] = new ListBox( 1, 2, "First List Box" ); winArray[1] = new ListBox( 3, 4, "Second List Box" ); winArray[2] = new Button( 5, 6 ); for ( int i = 0; i < 3; i++ ) { winArray[i].DrawWindow( ); } // end for loop } // end main } // end class Tester

The output looks like this:

Writing string to the listbox: First List Box

Writing string to the listbox: Second List Box

Drawing a button at 5, 6In Example 11-3,

the Window class has been declared

abstract and therefore cannot be instantiated. If you replace the first

array member:

winArray[0] = new ListBox(1,2,"First List Box");

with this code:

winArray[0] = new Window(1,2);

the program generates the following error at compile time:

Cannot create an instance of the abstract class or interface 'Window'

You can instantiate the ListBox

and Button objects because these

classes override the abstract method, thus making the classes

concrete (that is, not abstract).

Often an abstract class will include non-abstract methods. Typically, these will be marked virtual, providing the programmer who derives from your abstract class the choice of using the implementation provided in the abstract class, or overriding it. Once again, however, all abstract methods must, eventually, be overridden in order to make an instance of the (derived) class.

Sealed Classes

The opposite side of the design coin from abstract is

sealed . In contrast to an abstract class, which is intended to

be derived from and to provide a template for its subclasses to follow,

a sealed class does not allow classes to derive from it at all. The

sealed keyword placed before the

class declaration precludes derivation. Classes are most often marked

sealed to prevent accidental inheritance.

If you changed the declaration of Window in Example 11-3 from abstract to sealed (eliminating the abstract keyword from the DrawWindow( ) declaration as well), the

program fails to compile. If you try to build this project, the compiler

returns the following error message:

'ListBox' cannot inherit from sealed type 'Window'

among many other complaints (such as that you cannot create a new protected member in a sealed class).

Microsoft recommends using sealed when you know that you won’t need to create derived classes, and also when your class consists of nothing but static methods and properties.

The Root of All Classes: Object

All C# classes, of any type, ultimately derive from a

single class: Object. Object is the base class for all other

classes.

A base class is the immediate “parent” of a derived class. A

derived class can be the base to further derived classes, creating an

inheritance tree or hierarchy. A

root class is the topmost class in an inheritance hierarchy.

In C#, the root class is Object. The

nomenclature is a bit confusing until you imagine an upside-down tree,

with the root on top and the derived classes below. Thus, the base class

is considered to be “above” the derived class.

Object provides a number of

methods that subclasses can override. These include Equals( ), which determines if two objects are

the same, and ToString( ), which

returns a string to represent the current object. Specifically, ToString( ) returns a string with the name of

the class to which the object belongs. Table 11-1 summarizes the

methods of Object.

Method | What it does |

| Evaluates whether two objects are equivalent |

| Allows objects to provide their own hash function for use in collections (see Chapter 14) |

| Provides access to the Type object |

| Provides a string representation of the object |

| Cleans up nonmemory resources; implemented by a destructor (finalizer) |

In Example 11-4,

the Dog class overrides the ToString( ) method inherited from Object, to return the weight of the Dog.

using System;

public class Dog

{

private int weight;

// constructor

public Dog( int weight )

{

this.weight = weight;

}

// override Object.ToString

public override string ToString( )

{

return weight.ToString( );

}

}

public class Tester

{

static void Main( )

{

int i = 5;

Console.WriteLine( "The value of i is: {0}", i.ToString( ) );

Dog milo = new Dog( 62 );

Console.WriteLine( "My dog Milo weighs {0} pounds", milo);

}

}

Output:

The value of i is: 5

My dog Milo weighs 62 poundsSome classes (such as Console)

have methods that expect a string (such as Write-Line( )). These methods will call the

ToString( ) method on your class if

you’ve overridden the inherited ToString( ) method from Object. This

lets you pass a Dog to Console.WriteLine, and the correct information

will display.

This example also takes advantage of the startling fact that

intrinsic types (int, long, etc.) can also be treated as if they

derive from Object, and thus you can

call ToString( ) on an int variable! Calling ToString( ) on an intrinsic type returns a

string representation of the variable’s value.

The documentation for Object.ToString( ) reveals its signature:

public virtual string ToString( );

It is a public virtual method that returns a string and takes no

parameters. All the built-in types, such as int, derive from Object and so can invoke Object’s methods.

Tip

The Console class’s Write( ) and WriteLine( ) methods call ToString( ) for you on objects that you pass

in for display. Thus, by overriding ToString( ) in the Dog class, you

did not have to pass in milo.ToString( ) but rather could just pass in milo!

If you comment out the overridden function, the base method will be invoked. The base class default behavior is to return a string with the name of the class itself. Thus, the output would be changed to the meaningless:

My dog Milo weighs Dog pounds

Boxing and Unboxing Types

Boxing and

unboxing are the processes that enable value types (such as, integers) to be treated as reference types

(objects). The value is “boxed” inside an Object and subsequently “unboxed” back to a

value type. It is this process that allowed you to call the ToString( ) method on the integer in Example 11-4.

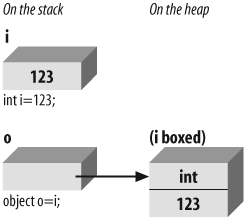

Boxing Is Implicit

Boxing is an implicit conversion of a value type to the type

Object. Boxing a value allocates an

instance of Object and copies the

value into the new object instance, as shown in Figure 11-4.

Boxing is implicit when you provide a value type where a reference is expected. The runtime notices that you’ve provided a value type and silently boxes it within an object. You can, of course, first cast the value type to a reference type, as in the following:

int myIntegerValue = 5;

object myObject = myIntegerValue; // cast to an object

myObject.ToString();This is not necessary, however, as the compiler boxes the value for you silently and with no action on your part:

int myIntegerValue = 5;

myIntegerValue.ToString(); // myIntegerValue is boxedUnboxing Must Be Explicit

To return the boxed object back to a value type, you must explicitly unbox it. For the unboxing to succeed, the object being unboxed must really be of the type you indicate when you unbox it.

You should accomplish unboxing in two steps:

Make sure the object instance is a boxed value of the given value type.

Copy the value from the instance to the value-type variable.

Example 11-5 illustrates boxing and unboxing.

using System;

public class UnboxingTest

{

public static void Main( )

{

int myIntegerVariable = 123;

//Boxing

object myObjectVariable = myIntegerVariable;

Console.WriteLine( "myObjectVariable: {0}",

myObjectVariable.ToString( ) );

// unboxing (must be explicit)

int anotherIntegerVariable = (int)myObjectVariable;

Console.WriteLine( "anotherIntegerVariable: {0}",

anotherIntegerVariable );

}

}

Output:

myObjectVariable: 123

anotherIntegerVariable: 123Figure 11-5 illustrates unboxing.

Example 11-5

creates an integer myIntegerVariable and implicitly boxes it

when it is assigned to the object myObjectVariable; then, to exercise the

newly boxed object, its value is displayed by calling ToString( ).

The object is then explicitly unboxed and assigned to a new

integer variable, anotherIntegerVariable, whose value is

displayed to show that the value has been preserved.

Avoiding Boxing with Generics

The most common place that value types were boxed in C#

1.x was in collections that expected Objects. Now that C# supports generics,

collections that hold integers need not box and unbox them, and that

can increase performance when you have a very large collection.

Generics are discussed in more detail in the Chapter 14.

Summary

Specialization is described as the is-a relationship; the reverse of specialization is generalization.

Specialization and generalization are reciprocal and hierarchical—that is, specialization is reciprocal to generalization, and each class can have any number of specialized derived classes but only one parent class that it specializes: thus creating a branching hierarchy.

C# implements specialization through inheritance.

The inherited class derives the public and protected characteristics and behaviors of the base class, and is free to add or modify its own characteristics and behaviors.

You implement inheritance by adding a colon after the name of the derived class, followed by the name of its base class.

A derived class can invoke the constructor of its base class by placing a colon after the parameter list and invoking the base class constructor with the keyword

base.Classes, like members, can also use the access modifiers

public,private, andprotected, though the vast majority of non-nested classes will be public.A method marked as

virtualin the base class can be overridden by derived classes if the derived classes use the keywordoverridein their method definition. This is the key to polymorphism in which you have a collection of references to a base class but each object is actually an instance of a derived class. When you call the virtual method on each derived object, the overridden behavior is invoked.A derived class can break the polymorphism of a derived method but must signal that intent with the keyword

new. This is unusual, complex and can be confusing, but is provided to allow for versioning of derived classes. Typically, you will use the keyword overrides (rather than new) to indicate that you are modifying the behavior of the base class’s method.A method marked as

abstracthas no implementation—instead, it provides a virtual method name and signature that all derived classes must override. Any class with an abstract method is an abstract class, and cannot be instantiated.Any class marked as

sealedcannot be derived from.In C#, all classes (and built-in types) are ultimately derived from the

Objectclass, implicitly, and thus inherit a number of useful methods such asToString.When you pass a value type to a method or collection that expects a reference type, the value type is “boxed” and must be explicitly “unboxed” when retrieved.

Generics make boxing and unboxing less common, and well-designed code will have little or no boxing or unboxing.

Quiz

- Question 11–1

What is the relationship between specialization and generalization?

- Question 11–2

How is specialization implemented in C#?

- Question 11–3

What is the syntax for inheritance in C#?

- Question 11–4

How do you implement polymorphism?

- Question 11–5

What are the two meanings of the keyword

new?- Question 11–6

How do you call a base class constructor from a derived class?

- Question 11–7

What is the difference between public, protected, and private?

- Question 11–8

What is an abstract method?

- Question 11–9

What is a sealed class?

- Question 11–10

What is the base class of Int32?

- Question 11–11

What is the base class of any class you create if you do not otherwise indicate a base class?

- Question 11–12

What is boxing?

- Question 11–13

What is unboxing?

Exercises

- Exercise 11-1

Create a base class,

Telephone, and derive a classElectronicPhonefrom it. InTelephone, create a protected string memberphonetype, and a public methodRing( )that outputs a text message like this: “Ringing the <phonetype>.” InElectronicPhone, the constructor should set thephonetypeto “Digital.” In theRun( )method, callRing( )on theElectronicPhoneto test the inheritance.- Exercise 11-2

Extend Exercise 11-1 to illustrate a polymorphic method. Have the derived class override the

Ring( )method to display a different message.- Exercise 11-3

Change the

Telephoneclass to abstract, and makeRing( )an abstract method. Derive two new classes fromTelephone:DigitalPhoneandTalkingPhone. Each derived class should set thephonetype, and override theRing( )method.

[8] In standard English, one uses “he” when the pronoun might refer either to a male or a female. Nonetheless, this assumption has such profound cultural implications, especially in the male-dominated programming profession, that I will use the term “she” for the unknown programmer from time to time. I apologize if this causes you to falter a bit when reading; consider it an opportunity to reflect on the linguistic implications of a patriarchal society.