Chapter 18. Creating Windows Applications

All the previous chapters have used console applications to demonstrate the C# language. This allowed us to focus on the language itself, without being distracted by more complicated issues such as windows, mice, and controls.

That said, the only reason most people learn C# is to create Windows applications or web applications, or both. On the following pages, you will learn how to create Windows applications using the tools provided by Visual Studio (the next chapter shows you how to create web applications).

The application you will create in this chapter will bring together a number of C# techniques shown in earlier chapters and apply them to solving a real-world problem.

Creating a Simple Windows Form

The .NET Framework offers extensive support for Windows application development, the centerpiece of which is Windows Forms. The metaphor of a “form” was borrowed from Visual Basic, and is a hallmark of Rapid Application Development (RAD ). Arguably, C# is the first development environment to marry the RAD tools of VB with the object-oriented and high-performance characteristics of a C++/Java-like language (though, of course, C# and Visual Basic 2005 are now virtually the same language with different syntactic coatings).

Using the Visual Studio Designer

While it is possible to build a Windows application using any text editor, and it is possible to compile from the command line, it is senseless to do so. Visual Studio 2005 increases your productivity, and integrates an editor, compiler, test environment, and debugger into a single work environment. Few serious .NET developers build commercial applications outside of Visual Studio.

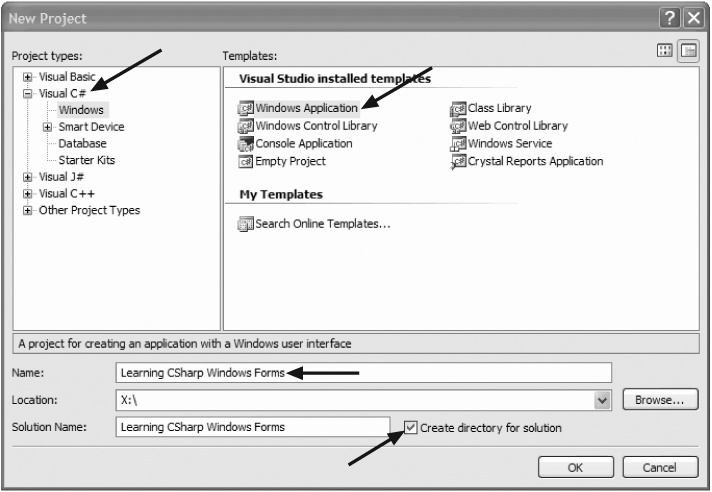

To begin work on a new Windows application, first open Visual Studio and choose File → New → Project. In the New Project window, create a new C# Windows application and name it Learning CSharp Windows Forms, as shown in Figure 18-1.

Be sure to choose C# and Windows Application (see arrows). It is convenient to place each project in its own directory (see checkbox), and you may name the project anything you like (and the name may include spaces, as shown).

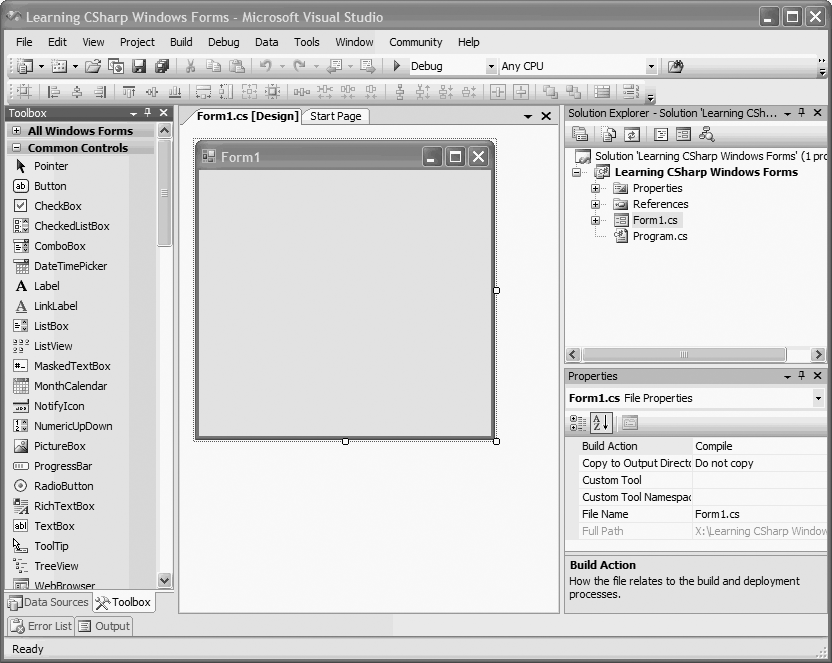

Visual Studio responds by creating a Windows Form application and, best of all, putting you into a design environment, as shown in Figure 18-2.

The Design window displays a blank Windows Form (Form1). A Toolbox window is also available, with a selection of Windows

controls. If the Toolbox is not displayed, try selecting View →

Toolbox on the Visual Studio menu. You can also use the keyboard

shortcut Ctrl/Alt/X to display the Toolbox.[12]

Before proceeding, take a look around. The Toolbox is filled with controls that you can add to your Windows Form application. In the upper-right corner, you should see the Solution Explorer, a window that displays all the files in your projects (if not, click View → Solution Explorer). In the lower-right corner is the Properties window (View → Properties Window), which displays all the properties of the currently selected item.

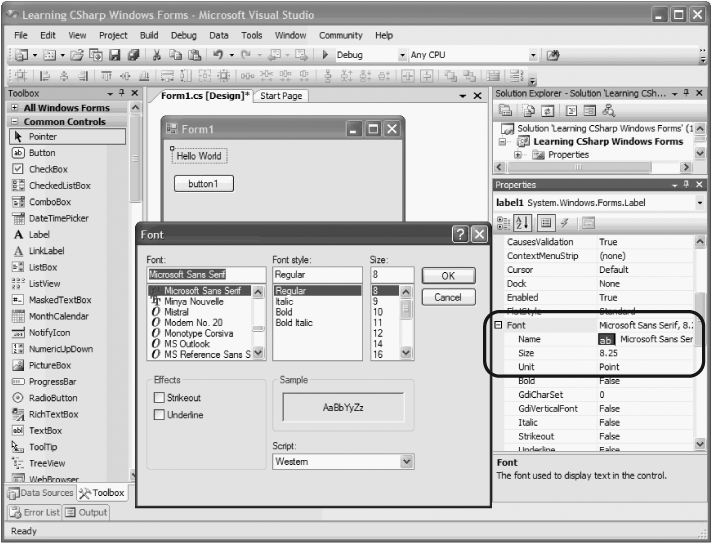

Drag a label and a button from the Toolbox onto the form. Click on the label and take a look at its properties in the Properties window, as shown in Figure 18-3.

To add text to label1, you

can type the words “Hello World” into the box to the right of its

Text property.

If you want to change the font for the lettering in the HelloWorld label, click the + sign next to

the Font property to expand it.

Then click on the ellipsis next to the Name sub-property to open the

Font editor, as shown in Figure 18-4.

Click on the button and change its text to Cancel. Run the application by clicking the Start Debugging button, or clicking F5, just as you would with a console application. You’ll see your new form running in its own window. Click on the Cancel button. Oops, nothing happens. For the application to respond to the button click, you must provide an event handler. Click on the X to close your application and return to the Design view.

Click on the button so that its properties are shown in the Properties window. Notice that at the top of the window are a series of buttons. As you hover the cursor over each, a tool tip tells you what it is for, as shown in Figure 18-5.

Click on the lightning bolt to change the Properties window to show all the events for the button. You’ll want to create a handler for the Click event. You can type a name into the space next to Click or you can just double-click in the space and Visual Studio 2005 will create an event handler name for you. In either case, Visual Studio 2005 then places you in the editor for the event handler so you can add the logic. Add a line to the event so it looks like this:

private void button1_Click( object sender, EventArgs e )

{

Application.Exit( );

}Visual Studio 2005 created the name by concatenating the control

name (button1) with the event

(Click), separated by an

underscore. Your logic just says to exit the application when the

button is clicked.

Tip

Every control has a “default” event—the event most commonly handled by that control. In the button’s case, the default event is click. You can save time by double-clicking on the control (in Design view) if you want Visual Studio 2005 to create and name an event handler for you. That is, rather than the steps above (click on the button, click on the lightning button, double-click on the space next to Click), you could have just double-clicked on the button; the effect would be the same because you are implementing the “default” event.

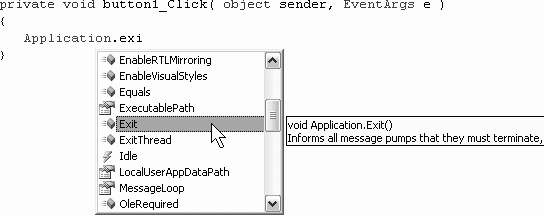

Notice that as you try to enter the method call Application.Exit( ) , Visual Studio 2005’s IntelliSense tries to help you. When you type A, the first possible

object that begins with A is shown. Continue typing through Appl and

then hit the period: the class Application is filled in for you, and the

methods and properties of the Application object are available.

Tip

IntelliSense will remember your most recent choice of member for a given class, and that will be displayed first. Often this is a great convenience.

Type Exi and IntelliSense

scrolls to the first method that begins with those letters, as shown

in Figure

18-6.

Once you’ve found the method, just type the parentheses and semicolon.

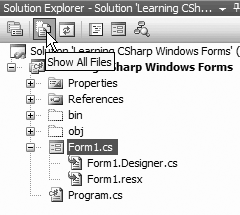

The partial Keyword

Your code file (Form1.cs) has only the using directives and the constructor and

event handler. If you have experience with previous versions of C#,

you may be wondering where the code to initialize the controls is

hiding. The class definition contains the keyword partial. This indicates that the rest of the

class definition is contained in another file. If you click the Show

All Files button at the top of the Solution Explorer (as shown in

Figure 18-7), you

will see that the designer has revealed another file, Form1.Designer.cs, that contains the

boiler-plate code and the initialization for all the controls.

Creating a Real-World Application

To see how Windows Forms can be used to create a more

realistic Windows application, you’ll build a utility named FileCopier that copies all files from a group of directories

selected by the user to a single target directory or device, such as a

floppy or backup hard drive on the company network. Although you won’t

implement every possible feature, this example will provide a good

introduction to what it is like to build meaningful Windows

applications.

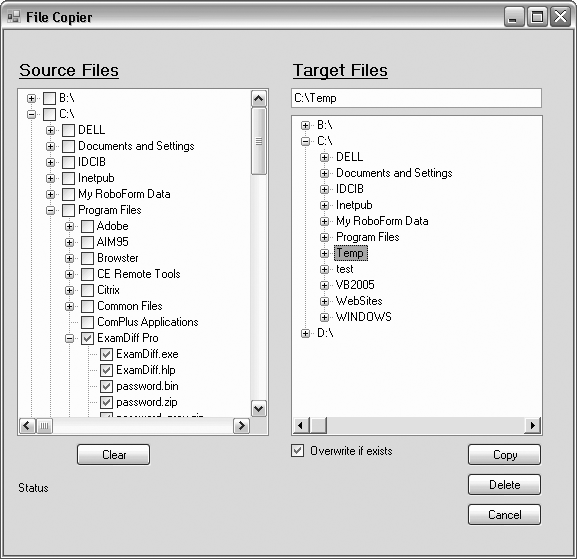

For the purposes of this example and to keep the code simple, you’ll focus on the user interface and the steps needed to wire up its various controls. The final application UI is shown in Figure 18-8.

The user interface for FileCopier consists of the following

controls:

Labels (Source Files, Target Files, and Status)

Buttons (Clear, Copy, Delete, and Cancel)

An “Overwrite if exists” checkbox

A text box displaying the path of the selected target directory

TreeView controls (source and target directories)

The goal is to allow the user to check files (or entire directories) in the left tree view (source). If the user clicks the Copy button, the files checked on the left side will be copied to the Target Directories specified on the right-side control. If the user clicks Delete, the checked files will be deleted.

Tip

The example you’re about to create is much more complex than anything you’ve done in this book so far. However, if you walk through the code slowly, you’ll find that you’ve already learned everything you need in the previous chapters. The goal of creating Windows applications is to mix drag-and-drop design with rather straightforward C# blocks to handle the logic.

Creating the Basic UI Form

The first task is to open a new project named

FileCopier. The IDE puts you into the designer, in which you can drag

widgets onto the form. You can expand the form to the size you want.

Drag, drop, and set the Name

properties of labels (lblSource,

lblTarget,

lblStatus), buttons

(btnClear,

btnCopy,

btnDelete,

btnCancel), a checkbox

(chkOverwrite), a text box

(txtTargetDir), and tree view controls

(tvwSource,

tvwTargetDir) from the Toolbox onto your

form. Then set the Text properties

of the widgets until it looks more or less like the one shown in Figure 18-9.

You want checkboxes next to the directories and files in the

source selection window, but not in the target (where only one

directory will be chosen). Set the CheckBoxes property on the left TreeView control,

tvwSource, to true, and set the property on the right

TreeView control,

tvwTargetDir, to false. To do so, click

each control in turn and adjust the values in the Properties

window.

Once this is done, double-click the Cancel button to create its click event handler, like this:

protected void btnCancel_Click (object sender, System.EventArgs e)

{

Application.Exit( );

}You can handle many different events for the various controls. An easy way to do so is by clicking the Events button in the Properties window. From there, you can create new handlers, just by filling in a new event handler method name or picking one of the existing event handlers. Visual Studio registers the event handler and opens the editor for the code, where it creates the header and puts the cursor in an empty method body.

So much for the easy part. Visual Studio generates code to set

up the form and initializes all the controls, but it doesn’t fill the

TreeView controls. That you must do

by hand.

Populating the TreeView Controls

The two TreeView

controls work identically, except that the left control, tvwSource, lists the directories and files,

whereas the right control, tvwTargetDir, lists only directories. The

CheckBoxes property on tvwSource is set to true, and on tvwTargetDir, it is set to false. Also, although tvwSource will allow multiselect, which is

the default for TreeView controls,

you will enforce single selection for tvwTargetDir.

You’ll factor the common code for both TreeView controls into a shared method

FillDirectoryTree. You’ll pass in

the treeview control with a boolean (also called a

flag) indicating whether to get the files that

are currently present (you’ll see how this works in a bit). You’ll

call this method from the Form’s constructor, once for each of the two

controls. Click on the Form1.cs tab at the top of the main window in

Visual Studio to switch to the code for the form. Locate the

constructor for the form (public Form1( )), and add these two method calls:

FillDirectoryTree(tvwSource, true);

FillDirectoryTree(tvwTargetDir, false);The FillDirectoryTree

implementation names the TreeView

parameter tvw. This will represent

the source TreeView and the

destination TreeView in turn.

You’ll need some classes from System.IO, so add a using System.IO statement at the top of

Form1.cs.

Next, add the method declaration to Form1.cs:

private void FillDirectoryTree(TreeView tvw, bool isSource)

Right now, the code for Form1.cs should look like this:

using System;

using System.Collections.Generic;

using System.ComponentModel;

using System.Data;

using System.Drawing;

using System.Text;

using System.Windows.Forms;

using System.IO;

namespace FileCopier

{

public partial class Form1 : Form

{

public Form1( )

{

InitializeComponent( );

FillDirectoryTree(tvwSource, true);

FillDirectoryTree(tvwTargerDir, false);

}

private void lblSource_Click(object sender, EventArgs e)

{

}

private void btnCancel_Click(object sender, EventArgs e)

{

Application.Exit( );

}

private void FillDirectoryTree(TreeView tvw, bool isSource)

{

}

}

}TreeNode objects

You’re now going to fill in the code for the FillDirectoryTree( ) method you just

created. The TreeView control has

a property, Nodes, which gets a

TreeNodeCollection object. The

TreeNodeCollection is a

collection of TreeNode objects,

each of which represents a node in the tree. Start by emptying that

collection.

tvw.Nodes.Clear( );

Tip

The TreeView, the

TreeNodeCollection, and the

TreeNode class are all defined

by the Framework Class Library, In fact, nearly all the classes

used in this example are defined by the framework (as opposed to

defined by you) and can be fully explored in the help

files.

There is, unfortunately, no accepted convention to

distinguish between individually user-defined classes (such as

frmFileCopier) from

framework-defined classes (such as Environment). On the other hand, if you

haven’t defined it explicitly, it is a safe bet that it is part of

the framework, and you can confirm that with the help files

documentation.

You are ready to fill the TreeView’s Nodes collection by recursing

through the directories of all the drives. First, you need to get

all the logical drives on the local system. To do so, call a static

method of the Environment object,

GetLogicalDrives( ). The Environment class provides information

about and access to the current platform environment. You can use

the Environment object to get the

machine name, OS version, system directory, and so forth, from the

computer on which you are running your program.

string[] strDrives = Environment.GetLogicalDrives( );

GetLogicalDrives( ) returns

an array of strings, each of which represents the root directory of

one of the logical drives. You will iterate over that collection,

adding nodes to the TreeView

control as you go.

foreach (string rootDirectoryName in strDrives)

{You process each drive within the foreach loop.

The very first thing you need to determine is whether the

drive is available (that is, it is not a floppy drive with no floppy

in it). My hack for that is to get the list of top-level directories

from the drive by calling GetDirectories( ) on a DirectoryInfo

object I created for the root directory:

DirectoryInfo dir = new DirectoryInfo(rootDirectoryName);

dir.GetDirectories( );The DirectoryInfo class

exposes instance methods for creating, moving, and enumerating

through directories, their files, and their subdirectories.

The GetDirectories( )

method returns a list of directories, but actually, this code throws

the list away. You are calling it here only to generate an exception

if the drive is not ready.

Wrap the call in a try

block and take no action in the catch block. The effect is that if an

exception is thrown, the drive is skipped.

Once you know that the drive is ready, create a TreeNode to hold the root directory of the

drive and add that node to the TreeView control:

TreeNode ndRoot = new TreeNode(rootDirectoryName);

tvw.Nodes.Add(ndRoot);To get the + signs right in the TreeView, you must find at least two

levels of directories (so that the TreeView knows which directories have

subdirectories and can write the + sign next to them). You don’t

want to recurse through all the subdirectories, however, because

that would be too slow.

The job of the GetSubDirectoryNodes( ) method is to recurse two levels deep, passing in the

root node, the name of the root directory, a flag indicating whether

you want files, and the current level (you always start at level

1):

if ( isSource )

{

GetSubDirectoryNodes(ndRoot, ndRoot.Text, true,1 );

}

else

{

GetSubDirectoryNodes(ndRoot, ndRoot.Text, false,1 );

}Tip

You may be wondering why you need to pass in ndRoot.Text if you’re already passing in

ndRoot. You will see why this

is needed when you recurse back into GetSubDirectoryNodes.

After the catch block, you

throw in the following line:

Application.DoEvents( );

This instructs the application to yield processing long enough to update the user interface. This keeps the user informed and happy, and avoids the problem of it looking like your program has hung while performing a long procedure.

You are now finished with FillDirectoryTree( ). See Example 18-1 later in this

chapter for a complete listing of this method.

Recursing through the subdirectories

Next, you need to create the method that gets the

subdirectory nodes. Create that in a new method following the one

you just finished. GetSubDirectoryNodes( ) begins by once again calling GetDirectories( ), this time stashing away

the resulting array of DirectoryInfo objects:

private void GetSubDireoctoryNodes(

TreeNode parentNode, string fullName, bool getFileNames, int level)

{

DirectoryInfo dir = new DirectoryInfo(fullName);

DirectoryInfo[] dirSubs = dir.GetDirectories( );Notice that the node passed in is named parentNode. The current level of nodes

will be considered children to the node passed in. This is how you

map the directory structure to the hierarchy of the tree

view.

Iterate over each subdirectory, skipping any that are marked

Hidden:

foreach (DirectoryInfo dirSub in dirSubs)

{

if ( (dirSub.Attributes & FileAttributes.Hidden) != 0 )

{

continue;

}FileAttributes is an

enum; other possible values

include Archive, Compressed, Directory, Encrypted, Normal, ReadOnly, and a few others, but they are

rarely used.

The property dirSub.Attributes is the bit pattern of

the current attributes of the directory. If you logically AND that value with the bit pattern

FileAttributes.Hidden, a bit is

set if the file has the hidden

attribute; otherwise, all the bits are cleared. You can check for

any hidden bit by testing whether the resulting int is something other than 0.

Next, create a TreeNode

with the directory name and add it to the Nodes collection of the node passed in to

the method (parentNode):

TreeNode subNode = new TreeNode(dirSub.Name);

parentNode.Nodes.Add(subNode);Check the current level (passed in by the calling method) against a constant defined for the class.

By convention, member constants and variables are declared at the top of the class declaration:

partial class frmFileCopier : Form

{

private const int MaxLevel = 2;The constant makes sure you recurse only two levels deep. The

following snippet is back in the foreach loop within GetSubDirectoryNodes:

if ( level < MaxLevel )

{

GetSubDirectoryNodes(subNode, dirSub.FullName, getFileNames, level+1 );

}Tip

You pass in the node you just created as the new parent, the full path as the full name of the parent, and the flag you received, along with one greater than the current level (thus, if you started at level one, this next call will set the level to two).

The call to the TreeNode

constructor uses the Name

property of the DirectoryInfo

object, while the call to GetSubDirectoryNodes( ) uses the FullName property. If your directory is

C:\Windows\Media\Sounds, the

FullName property returns the

full path, while the Name

property returns just Sounds. Pass in only the

name to the node because that is what you want displayed in the tree

view. Pass in the full name with the path to the GetSubDirectoryNodes( ) method so that the

method can locate all the subdirectories on the disk. This answers

the question asked earlier as to why you need to pass in the root

node’s name the first time you call this method. What is passed in

isn’t the name of the node; it is the full path to the directory

represented by the node!

Getting the files in the directory

Once you’ve recursed through the subdirectories, it is time to

get the files for the directory if the getFileNames flag is true. To do so, call the GetFiles( ) method on the DirectoryInfo object. An array of FileInfo objects is returned:

if (getFileNames)

{

// Get any files for this node.

FileInfo[] files = dir.GetFiles( );The FileInfo class provides

instance methods for manipulating files.

You can now iterate over this collection, accessing the

Name property of the FileInfo object and passing that name to

the constructor of a TreeNode,

which you then add to the parent node’s Nodes collection (thus creating a child

node). There is no recursion this time because files don’t have

subdirectories:

foreach (FileInfo file in files)

{

TreeNode fileNode = new TreeNode(file.Name);

parentNode.Nodes.Add(fileNode);

}That’s all it takes to fill the two tree views. See Example 18-1 for a complete listing of this method.

If you found any of this confusing, I highly recommend building Example 18-1 and stepping through the code in the Visual Studio 2005 debugger. Pay particular attention to the recursion, watching as the TreeView build its nodes.

Handling TreeView Events

You must handle a number of events in this example. First, the user might click Cancel, Copy, Clear, or Delete. Second, the user might fire events in either TreeView. We’ll consider the TreeView events first, as they are the more interesting, and potentially the more challenging.

Clicking the source TreeView

There are two TreeView

objects, each with its own event handler. Consider the source

TreeView object first. The user

checks the files and directories he wants to copy from. Each time

the user clicks the checkbox indicating a file or directory, a

number of events are raised. The event you must handle is AfterCheck.

To do so, implement a custom event handler method you will

create and name tvwSource_AfterCheck( ).The implementation of AfterCheck( ) delegates the work to a

recursable method named SetCheck( ) that you’ll also write. The SetCheck( ) method will recursively set

the check mark for all the contained folders.

To add the AfterCheck( )

event, select the tvwSource

control, click the Events icon in the Properties window, and then

double-click AfterCheck. This will add the event, wire it up, and

place you in the code editor where you can add the body of the

method:

private void tvwSource_AfterCheck (

object sender, System.Windows.Forms.TreeViewEventArgs e)

{

SetCheck(e.Node,e.Node.Checked);

}The event handler passes in the sender object and an object of

type TreeViewEventArgs. It turns

out that you can get the node from this TreeViewEventArgs object (e). You then call SetCheck( ), passing in the node and the

state of whether the node has been checked.

Each node has a Nodes

property, which gets a TreeNodeCollection containing all the

subnodes. SetCheck( ) recurses

through the current node’s Nodes

collection, setting each subnode’s check mark to match that of the

node that was checked. In other words, when you check a directory,

all its files and subdirectories are checked, recursively, all the

way down.

For each TreeNode in the

Nodes collection, check to see if

it is a leaf. A node is a leaf if its own Nodes collection has a count of 0. If it

is a leaf, set its check property to whatever was passed in as a

parameter. If it is not a leaf, recurse:

private void SetCheck( TreeNode node, bool check )

{

foreach ( TreeNode n in node.Nodes )

{

n.Checked = check; // check the node

if ( n.Nodes.Count != 0 )

{

SetCheck( n, check );

}

}

}This propagates the check mark (or clears the check mark) down through the entire structure. In this way, the user can indicate that he wants to select all the files in all the subdirectories by clicking a single directory.

Expanding a directory

Each time you click a + sign next to a directory in

the source (or in the target), you want to expand that directory. To

do so, you’ll need an event handler for the BeforeExpand event. Because the event handlers will be identical

for both the source and the target tree views, you’ll create a

shared event handler (assigning the same event handler to both). Go

back to the Design view, select the tvwSource control, double-click the

BeforeExpand event, and add this

code:

private void tvwExpand(object sender, TreeViewCancelEventArgs e)

{

TreeView tvw = ( TreeView ) sender;

bool getFiles = tvw == tvwSource;

TreeNode currentNode = e.Node;

string fullName = currentNode.FullPath;

currentNode.Nodes.Clear( );

GetSubDirectoryNodes( currentNode, fullName, getFiles, 1 );

}Your second task is to determine whether you want to get the

files in the directory you are opening, and you do only if the name

of the TreeView that triggered

the event is tvwSource.

You determine which node’s + sign was checked by getting the

Node property from the TreeViewCancelEventArgs that is passed in

by the event:

TreeNode currentNode = e.Node;

Once you have the current node, you get its full pathname

(which you will need as a parameter to GetSubDirectoryNodes) and then you must

clear its collection of subnodes, because you are going to refill

that collection by calling in to GetSubDirectoryNodes:

currentNode.Nodes.Clear( );

Why do you clear the subnodes and then refill them? Because this time you will go another level deep so that the subnodes know if they in turn have subnodes, and thus will know if they should draw a + sign next to their subdirectories.

Be sure to select the target TreeView and add the same code to its

BeforeExpand event.

Clicking the target TreeView

The second event handler for the target TreeView (in addition to BeforeExpand) is somewhat trickier. The

event itself is AfterSelect.

(Remember that the target TreeView doesn’t have checkboxes.) This

time, you want to take the one directory chosen and put its full

path into the text box at the upper-left corner of the form.

To do so, you must work your way up through the nodes, finding the name of each parent directory and building the full path:

private void tvwTargetDir_AfterSelect (

object sender, System.Windows.Forms.TreeViewEventArgs e)

{

string theFullPath = GetParentString(e.Node);We’ll look at GetParentString( ) in just a moment. Once you have the full path, you must

lop off the backslash (if any) on the end, and then you can fill the

text box:

if (theFullPath.EndsWith("\\"))

{

theFullPath = theFullPath.Substring(0,theFullPath.Length - 1);

}

txtTargetDir.Text = theFullPath;The GetParentString( )

method takes a node and returns a string with the full path. To do

so, it recurses upward through the path, adding the backslash after

any node that is not a leaf:

private string GetParentString( TreeNode node )

{

if ( node.Parent == null )

{

return node.Text;

}

else

{

return GetParentString( node.Parent ) + node.Text +

( node.Nodes.Count == 0 ? String.Empty : "\\" );

}

}You learned about the conditional operator (?) in Chapter 4. The logic is, “Test

whether node.Nodes.Count is 0; if

so, return the value before the colon (in this case, an empty

string). Otherwise, return the value after the colon (in this case,

a backslash).”

The recursion stops when there is no parent; that is, when you hit the root directory.

Handling the Clear button event

Given the SetCheck( ) method developed earlier, handling the Clear button’s

Click event is trivial:

private void btnClear_Click( object sender, System.EventArgs e )

{

foreach ( TreeNode node in tvwSource.Nodes )

{

SetCheck( node, false );

}

}Just call the SetCheck( )

method on the root nodes and tell them to recursively uncheck all

their contained nodes.

Implementing the Copy Button Event

Now that you can check the files and pick the target

directory, you’re ready to handle the Copy click event. The very first thing you

need to do is to get a list of which files were selected. What you

want is an array of FileInfo

objects, but you have no idea how many objects will be in the list.

This is a perfect job for a generic List. Delegate responsibility for

filling the list to a method called GetFileList( ):

private void btnCopy_Click( object sender, System.EventArgs e )

{

List<FileInfo> fileList = GetFileList( );Let’s pick that method apart before returning to the event handler.

Start by instantiating a new List object to hold the strings representing

the names of all the files selected:

private List<FileInfo> GetFileList( )

{

List<string> fileNames = new List<string>( );To get the selected filenames, you can walk through the source

TreeView control:

foreach ( TreeNode theNode in tvwSource.Nodes )

{

GetCheckedFiles( theNode, fileNames );

}To see how this works, step into the GetCheckedFiles( ) method. This method is

pretty simple: it examines the node it was handed. If that node has no

children (node. Nodes.Count == 0),

it is a leaf. If that leaf is checked, get the full path (by calling

GetParentString( ) on the node) and

add it to the ArrayList passed in

as a parameter:

private void GetCheckedFiles( TreeNode node,List<string> fileNames )

{

// if this is a leaf...

if ( node.Nodes.Count == 0 )

{

// if the node was checked...

if ( node.Checked )

{

// get the full path and add it to the arrayList

string fullPath = GetParentString( node );

fileNames.Add( fullPath );

}

}If the node is not a leaf, recurse down the tree, finding the child nodes:

else

{

foreach (TreeNode n in node.Nodes)

{

GetCheckedFiles(n,fileNames);

}

}

}This returns the List filled

with all the filenames. Back in GetFileList( ), you use this List of

filenames to create a second List,

this time to hold the actual FileInfo objects:

List<FileInfo> fileList = new List<FileInfo>( );

Notice the use of typesafe List objects to ensure that the compiler

flags any objects added to the collection that aren’t of type FileInfo.

Back in GetFileList( ), you

can now iterate through the filenames in fileList, picking out each name and

instantiating a FileInfo object

with it. You can detect if it is a file or a directory by calling the

Exists property, which will return

false if the File object you created is actually a

directory. If it is a File, you can

add it to the new ArrayList:

foreach ( string fileName in fileNames )

{

FileInfo file = new FileInfo( fileName );

if ( file.Exists )

{

// both the key and the value are the file

// would it be easier to have an empty value?

fileList.Add( file );

}

}Sorting the list of selected files

You want to work your way through the list of selected

files in large to small order so that you can pack the target disk

as tightly as possible. You must therefore sort the List. You can call its Sort( ) method, but how will it know how

to sort FileInfo objects?

To solve this, you must pass in an IComparer<T> interface. We’ll create

a class called FileComparer that

will implement this generic interface for FileInfo objects:

public class FileComparer : IComparer<FileInfo>

{This class has only one method, Compare( ), which takes two FileInfo objects as arguments:

public int Compare(FileInfo file1, FileInfo file2);

The normal approach is to return 1 if the first object

(file1) is larger than the second

(file2), to return -1 if the

opposite is true, and to return 0 if they are equal. In this case,

however, you want the list sorted from big to small, so you should

reverse the return values.

Tip

Because this is the only use of the Compare method, it is reasonable to put

this special knowledge (that the sort is from big to small) right

into the Compare method itself.

The alternative is to sort small to big, and have the

calling method reverse the results.

To test the length of the FileInfo object, you must cast the

Object parameters to FileInfo objects (which is safe because

you know this method will never receive anything else):

public int Compare(FileInfo file1, FileInfo file2)

{

if ( file1.Length > file2.Length )

{

return -1;

}

if ( file1.Length < file2.Length )

{

return 1;

}

return 0;

}Returning to GetFileList( ), you were about to instantiate the IComparer reference and pass it to the

Sort( ) method of fileList:

IComparer<FileInfo> comparer = ( IComparer<FileInfo> ) new FileComparer( );

fileList.Sort( comparer );That done, you can return fileList to the calling method:

return fileList;

The calling method was btnCopy_Click. Remember, you went off to

GetFileList( ) in the first line

of the event handler!

protected void btnCopy_Click (object sender, System.EventArgs e)

{

List<FileInfo> fileList = GetFileList( );At this point, you’ve returned with a sorted list of File objects, each representing a file

selected in the source TreeView.

You can now iterate through the list, copying the files and updating the UI:

foreach ( FileInfo file in fileList )

{

try

{

lblStatus.Text = "Copying " + txtTargetDir.Text +

"\\" + file.Name + "...";

Application.DoEvents( );

// copy the file to its destination location

file.CopyTo( txtTargetDir.Text + "\\" +

file.Name, chkOverwrite.Checked );

}

catch ( Exception ex )

{

MessageBox.Show( ex.Message );

}

}

lblStatus.Text = "Done.";As you go, write the progress to the lblStatus label and call Application.DoEvents( ) to give the UI an

opportunity to redraw. Then call CopyTo( ) on the file, passing in the target directory obtained

from the text field, and a Boolean flag indicating whether the file

should be overwritten if it already exists.

The copy is wrapped in a try block because you can anticipate any

number of things going wrong when copying files. For now, handle all

exceptions by popping up a dialog box with the error; you might want

to take corrective action in a commercial application.

That’s it; you’ve implemented file copying!

Handling the Delete Button Event

The code to handle the Delete event is even more simple. The very

first thing you do is ask the user if she is sure she wants to delete

the files:

private void btnDelete_Click( object sender, System.EventArgs e )

{

// ask them if they are sure

System.Windows.Forms.DialogResult result =

MessageBox.Show(

"Are you quite sure?", // msg

"Delete Files", // caption

MessageBoxButtons.OKCancel, // buttons

MessageBoxIcon.Exclamation, // icons

MessageBoxDefaultButton.Button2 ); // default buttonYou can use the MessageBox

static Show( ) method, passing in

the message you want to display, the title "Delete Files" as a string, and flags, as

follows: MessageBox.OKCancel asks

for two buttons: OK and Cancel. MessageBox.IconExclamation indicates that

you want to display an exclamation mark icon. MessageBox.DefaultButton.Button2 sets the

second button (Cancel) as the

default choice.

When the user chooses OK or Cancel, the result is passed back as

a System.Windows. Forms.DialogResult enumerated value. You can test this value

to see if the user selected OK:

if ( result == System.Windows.Forms.DialogResult.OK )

{If so, you can get the list of fileNames and iterate through it, deleting

each as you go:

List<FileInfo> fileNames = GetFileList( );

foreach ( FileInfo file in fileNames )

{

try

{

// update the label to show progress

lblStatus.Text = "Deleting " +

txtTargetDir.Text + "\\" +

file.Name + "...";

Application.DoEvents( );

// Danger Will Robinson!

file.Delete( );

}

catch ( Exception ex )

{

// you may want to do more than

// just show the message

MessageBox.Show( ex.Message );

}

}

lblStatus.Text = "Done.";

Application.DoEvents( );This code is identical to the copy code, except that the method

that is called on the file is Delete( ).

Example 18-1 provides the commented source code for this example.

using System;

using System.Collections;

using System.Collections.Generic; // for List<T>

using System.ComponentModel;

using System.Data;

using System.Drawing;

using System.IO;

using System.Windows.Forms;

/// <remarks>

/// File Copier - Windows Forms demonstration program

/// (c) Copyright 2006 Liberty Associates, Inc.

/// </remarks>

namespace FileCopier

{

/// <summary>

/// Form demonstrating Windows Forms implementation

/// </summary>

partial class frmFileCopier : Form

{

private const int MaxLevel = 2;

public frmFileCopier( )

{

InitializeComponent( );

FillDirectoryTree( tvwSource, true );

FillDirectoryTree( tvwTarget, false );

}

/// <summary>

/// nested class which knows how to compare

/// two files we want to sort large to small,

/// so reverse the normal return values.

/// </summary>

public class FileComparer : IComparer<FileInfo>

{

public int Compare( FileInfo file1, FileInfo file2 )

{

if ( file1.Length > file2.Length )

{

return -1;

}

if ( file1.Length < file2.Length )

{

return 1;

}

return 0;

}

public bool Equals( FileInfo x, FileInfo y )

{

throw new NotImplementedException( );

}

public int GetHashCode( FileInfo x )

{

throw new NotImplementedException( );

}

}

/// <summary>

/// Factored out method for both directory trees

/// </summary>

/// <param name="tvw">which treeview called this handler</param>

/// <param name="isSource">get the files if true</param>

private void FillDirectoryTree( TreeView tvw, bool isSource )

{

// Populate tvwSource, the Source TreeView,

// with the contents of

// the local hard drive.

// First clear all the nodes.

tvw.Nodes.Clear( );

// Get the logical drives and put them into the

// root nodes. Fill an array with all the

// logical drives on the machine.

string[] strDrives = Environment.GetLogicalDrives( );

// Iterate through the drives, adding them to the tree.

// Use a try/catch block, so if a drive is not ready,

// e.g. an empty floppy or CD,

// it will not be added to the tree.

foreach ( string rootDirectoryName in strDrives )

{

try

{

// Fill an array with all the first level

// subdirectories. If the drive is

// not ready, this will throw an exception.

DirectoryInfo dir =

new DirectoryInfo( rootDirectoryName );

dir.GetDirectories( ); // force exception if drive not ready

TreeNode ndRoot = new TreeNode( rootDirectoryName );

// Add a node for each root directory.

tvw.Nodes.Add( ndRoot );

// Add subdirectory nodes.

// If Treeview is the source,

// then also get the filenames.

if ( isSource )

{

GetSubDirectoryNodes(

ndRoot, ndRoot.Text, true, 1 );

}

else

{

GetSubDirectoryNodes(

ndRoot, ndRoot.Text, false, 1 );

}

}

// Catch any errors such as

// Drive not ready.

catch

{

}

Application.DoEvents( );

} // end foreach rootdirectory name

} // end FillSourceDirectoryTree

/// <summary>

/// Gets all the subdirectories below the

/// passed in directory node.

/// Adds to the directory tree.

/// The parameters passed in are the parent node

/// for this subdirectory,

/// the full path name of this subdirectory,

/// and a Boolean to indicate

/// whether or not to get the files in the subdirectory.

/// </summary>

private void GetSubDirectoryNodes(

TreeNode parentNode, string fullName, bool getFileNames, int level )

{

DirectoryInfo dir = new DirectoryInfo( fullName );

DirectoryInfo[] dirSubs = dir.GetDirectories( );

// Add a child node for each subdirectory.

foreach ( DirectoryInfo dirSub in dirSubs )

{

// do not show hidden folders

if ( ( dirSub.Attributes & FileAttributes.Hidden )

!= 0 )

{

continue;

}

/// <summary>

/// Each directory contains the full path.

/// We need to split it on the backslashes,

/// and only use

/// the last node in the tree.

/// Need to double the backslash since it

/// is normally

/// an escape character

/// </summary>

TreeNode subNode = new TreeNode( dirSub.Name );

parentNode.Nodes.Add( subNode );

// Call GetSubDirectoryNodes recursively.

if ( level < MaxLevel )

{

GetSubDirectoryNodes(

subNode, dirSub.FullName, getFileNames, level + 1 );

}

} // end foreach DirectoryInfo in dirSubs

if ( getFileNames )

{

// Get any files for this node.

FileInfo[] files = dir.GetFiles( );

// After placing the nodes,

// now place the files in that subdirectory.

foreach ( FileInfo file in files )

{

TreeNode fileNode = new TreeNode( file.Name );

parentNode.Nodes.Add( fileNode );

} // end foreach FileInfo in files

} // end if get FileNames

} // end GetSubDirectoryNodes method

/// <summary>

/// Create an ordered list of all

/// the selected files, copy to the

/// target directory

/// </summary>

private void btnCopy_Click( object sender,

System.EventArgs e )

{

// get the list

List<FileInfo> fileList = GetFileList( );

// copy the files

foreach ( FileInfo file in fileList )

{

try

{

// update the label to show progress

lblStatus.Text = "Copying " + txtTargetDir.Text +

"\\" + file.Name + "...";

Application.DoEvents( );

// copy the file to its destination location

file.CopyTo( txtTargetDir.Text + "\\" +

file.Name, chkOverwrite.Checked );

}

catch ( Exception ex )

{

// you may want to do more than

// just show the message

MessageBox.Show( ex.Message );

}

} // end foreach FileInfo in fileList

lblStatus.Text = "Done.";

}

/// <summary>

/// Tell the root of each tree to uncheck

/// all the nodes below

/// </summary>

private void btnClear_Click( object sender, System.EventArgs e )

{

// get the top most node for each drive

// and tell it to clear recursively

foreach ( TreeNode node in tvwSource.Nodes )

{

SetCheck( node, false );

}

}

/// <summary>

/// on cancel, exit

/// </summary>

private void btnCancel_Click( object sender, EventArgs e )

{

Application.Exit( );

}

/// <summary>

/// Given a node and an array list

/// fill the list with the names of

/// all the checked files

/// </summary>

// Fill the List with the full paths of

// all the files checked

private void GetCheckedFiles( TreeNode node,

List<string> fileNames )

{

// if this is a leaf...

if ( node.Nodes.Count == 0 )

{

// if the node was checked...

if ( node.Checked )

{

// get the full path and add it to the List

string fullPath = GetParentString( node );

fileNames.Add( fullPath );

}

}

else // if this node is not a leaf

{

// if this node is not a leaf

foreach ( TreeNode n in node.Nodes )

{

GetCheckedFiles( n, fileNames );

}

}

}

/// <summary>

/// Given a node, return the

/// full path name

/// </summary>

private string GetParentString( TreeNode node )

{

// if this is the root node (c:\) return the text

if ( node.Parent == null )

{

return node.Text;

}

else

{

// recurse up and get the path then

// add this node and a slash

// if this node is the leaf, don't add the slash

return GetParentString( node.Parent ) + node.Text +

( node.Nodes.Count == 0 ? "" : "\\" );

} // end else

} // end GetParentString method

/// <summary>

/// shared by delete and copy

/// creates an ordered list of all

/// the selected files

/// </summary>

private List<FileInfo> GetFileList( )

{

// create an unsorted array list of the full file names

List<string> fileNames = new List<string>( );

// fill the fileNames List with the

// full path of each file to copy

foreach ( TreeNode theNode in tvwSource.Nodes )

{

GetCheckedFiles( theNode, fileNames );

}

// Create a list to hold the FileInfo objects

List<FileInfo> fileList = new List<FileInfo>( );

// for each of the file names we have in our unsorted list

// if the name corresponds to a file (and not a directory)

// add it to the file list

foreach ( string fileName in fileNames )

{

// create a file with the name

FileInfo file = new FileInfo( fileName );

// see if it exists on the disk

// this fails if it was a directory

if ( file.Exists )

{

// both the key and the value are the file

// would it be easier to have an empty value?

fileList.Add( file );

} // end if file exists

} // end foreach filename in filenames

// Create an instance of the IComparer interface

IComparer<FileInfo> comparer = (IComparer<FileInfo>)new FileComparer( );

// pass the comparer to the sort method so that the list

// is sorted by the compare method of comparer.

fileList.Sort( comparer );

return fileList;

}

/// <summary>

/// check that the user does want to delete

/// Make a list and delete each in turn

/// </summary>

private void btnDelete_Click( object sender, System.EventArgs e )

{

// ask them if they are sure

System.Windows.Forms.DialogResult result =

MessageBox.Show(

"Are you quite sure?", // msg

"Delete Files", // caption

MessageBoxButtons.OKCancel, // buttons

MessageBoxIcon.Exclamation, // icons

MessageBoxDefaultButton.Button2 ); // default button

// if they are sure...

if ( result == System.Windows.Forms.DialogResult.OK )

{

// iterate through the list and delete them.

// get the list of selected files

List<FileInfo> fileNames = GetFileList( );

foreach ( FileInfo file in fileNames )

{

try

{

// update the label to show progress

lblStatus.Text = "Deleting " +

txtTargetDir.Text + "\\" +

file.Name + "...";

Application.DoEvents( );

// Danger Will Robinson!

file.Delete( );

}

catch ( Exception ex )

{

// you may want to do more than

// just show the message

MessageBox.Show( ex.Message );

} // end catch

} // end foreach FileInfo in filenames

lblStatus.Text = "Done.";

Application.DoEvents( );

} // end if result = OK

} // end btnDelete_Click handler

/// <summary>

/// Get the full path of the chosen directory

/// copy it to txtTargetDir

/// </summary>

private void tvwTargetDir_AfterSelect(

object sender,

System.Windows.Forms.TreeViewEventArgs e )

{

// get the full path for the selected directory

string theFullPath = GetParentString( e.Node );

// if it is not a leaf, it will end with a back slash

// remove the backslash

if ( theFullPath.EndsWith( "\\" ) )

{

theFullPath =

theFullPath.Substring( 0, theFullPath.Length - 1 );

}

// insert the path in the text box

txtTargetDir.Text = theFullPath;

}

/// <summary>

/// Mark each node below the current

/// one with the current value of checked

/// </summary>

private void tvwSource_AfterCheck( object sender,

System.Windows.Forms.TreeViewEventArgs e )

{

// Call a recursible method.

// e.node is the node which was checked by the user.

// The state of the check mark is already

// changed by the time you get here.

// Therefore, we want to pass along

// the state of e.node.Checked.

SetCheck( e.Node, e.Node.Checked );

}

/// <summary>

/// recursively set or clear check marks

/// </summary>

private void SetCheck( TreeNode node, bool check )

{

// find all the child nodes from this node

foreach ( TreeNode n in node.Nodes )

{

n.Checked = check; // check the node

// if this is a node in the tree, recurse

if ( n.Nodes.Count != 0 )

{

SetCheck( n, check );

} // end if Nodes.Count not zero

} // end foreach TreeNode in Nodes

} // end SetCheck method

/// <summary>

/// Common event handler for beforeExpand event

/// </summary>

/// <param name="sender"></param>

/// <param name="e"></param>

private void tvwExpand( object sender, TreeViewCancelEventArgs e )

{

TreeView tvw = (TreeView)sender;

bool getFiles = tvw == tvwSource;

TreeNode currentNode = e.Node;

string fullName = currentNode.FullPath;

currentNode.Nodes.Clear( );

GetSubDirectoryNodes( currentNode, fullName, getFiles, 1 );

} // end tvwExpand handler

} // end frmFileCopier class

} // end FileCopier namespaceXML Documentation Comments

C# supports a new documentation

comment style, with three slash marks (///). You can see these comments sprinkled

throughout Example 18-1.

The Visual Studio editor recognizes these comments and helps format them

properly.

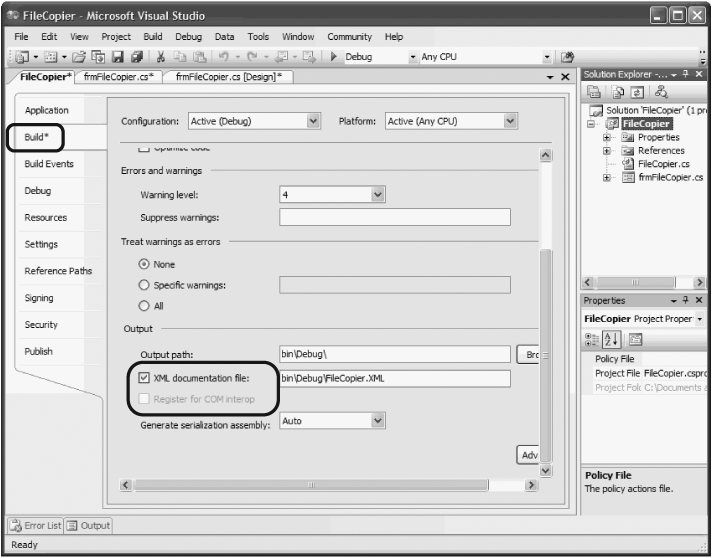

The C# compiler processes these comments into an XML file

You can generate the documentation in Visual Studio by clicking the FileCopier project icon in the Solution Explorer window, selecting View Property Pages on the Visual Studio menu, and then clicking Properties. Click the Build tab and then click the XML Documenation file and provide a path for where the XML should be placed, as shown in Figure 18-10.

Click the XML Documentation File checkbox and type in a name for the XML file you want to produce, such as Filecopier.XML. Rebuild the application.

Tip

In at least some versions of Visual C# 2005 Express, you accomplish this by clicking the Properties button in the Solution Explorer window. Please check the documentation for the version of Visual Studio 2005 you are using.

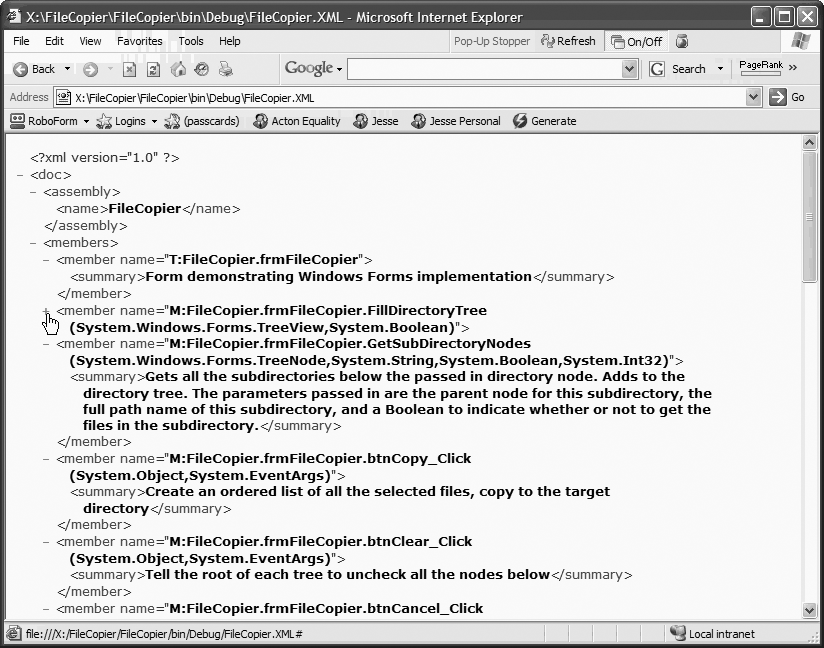

An excerpt of the file that’s produced for the FileCopier application of the previous section

is shown in Example

18-2.

<?xml version="1.0"?>

<doc>

<assembly>

<name>FileCopier</name>

</assembly>

<members>

<member name="T:FileCopier.frmFileCopier">

<summary>

Form demonstrating Windows Forms implementation

</summary>

</member>

<member name="M:FileCopier.frmFileCopier.FillDirectoryTree(System.Windows.Forms.

TreeView,System.Boolean)">

<summary>

Factored out method for both directory trees

</summary>

<param name="tvw">which treeview called this handler</param>

<param name="isSource">get the files if true</param>

</member>The file is quite long, and although it can be read by humans, it isn’t especially useful in that format. You could, however, write an XSLT file to translate the XML into HTML, or you could read the XML document into a database of documentation. You can also drag the file from File Explorer into Windows Explorer, which provides a nice interface for reading the XML, as shown in Figure 18-11.

Internet Explorer provides a number of handy features for reading XML files, including the ability to expand and collapse nodes (see the + and − signs to the left of each node).

Summary

C# and Visual Studio 2005 are designed to create Windows and web applications as well as web services.

Visual Studio provides visual design tools that enable you to drag-and-drop controls onto a form.

The Properties window allows you to change the properties of a control without having to edit the code by hand.

The events window helps you to create event handlers for all the possible events for your control. Simply double-click the event, and Visual Studio 2005 will create a skeleton event handler, and then take you to the appropriate point in the code, so you can enter your logic.

The

partialkeyword in the class definition indicates that the code to initialize the controls is in another file, ending with Designer.cs, that you can locate with the Solution Explorer.C# can automatically generate documentation in XML based on comments marked with three slashes in the code (

///).

Quiz

- Question 18–1

How can you set the properties of a control?

- Question 18–2

How do you make a button respond to being clicked?

- Question 18–3

Name two ways to create an event handler.

- Question 18–4

What is recursion?

- Question 18–5

What are the XML documentation comments?

- Question 18–6

How do you see the code created by Visual Studio 2005 to create and initialize the controls on the form?

Exercises

- Exercise 18-1

Create a Windows application that displays the word “Hello” in a label, and has a button that changes the display to “Goodbye.”

- Exercise 18-2

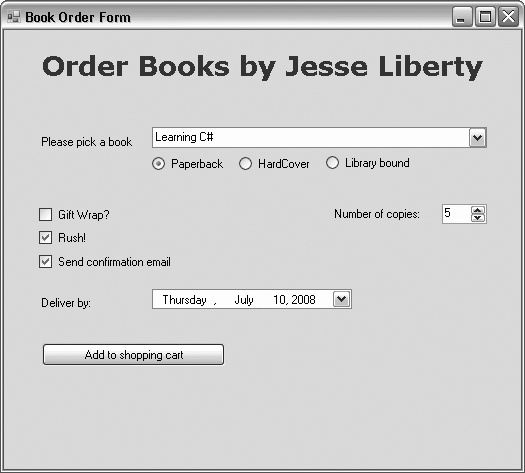

Create a Windows application that presents an order form that looks like Figure 18-12.

This figure represents an order form that that lets the user enter information through various controls such as buttons, checkboxes, radio buttons, DateTimePicker, and so forth. You don’t need to write the back-end for the ordering system, but you can do the following:

Simulate saving to the shopping cart with a message, and reset the form when the “Add to Shopping Cart” button is clicked.

Set the minimum delivery date to be two days from now, and let the user select later dates.

- Exercise 18-3

Modify the first exercise by dragging a timer (found in the Components section of the Toolbox) onto the form and having the timer change the message from “Hello” to “Goodbye” and back once per second. Change the button to turn this behavior on and off. Use the Microsoft Help files to figure out how to use the timer to accomplish this exercise.

[12] Visual Studio allows a great deal of personalization; please verify all the keyboard shortcuts mentioned in this book to ensure that they work as expected in your environment.