CHAPTER EIGHT

Healthy Building Certification Systems

Education is not a product: mark, diploma, job, money—in that order; it is a process, a never-ending one.

—BEL KAUFMAN

WHEN YOU GRADUATE FROM COLLEGE, it doesn’t really feel official until you have that diploma in hand—you put in the work, and now you want something to hang behind your desk to let the world know about your accomplishment. It’s proof that, at least at one point in time, you were “certified” with some level of expertise in whatever you studied. This facilitates the selection of doctors, accountants, or lawyers, for example; clients can rely on the certificate without having to individually test the provider’s knowledge of organic chemistry, depreciation, or patent law.

The same can be said about our buildings. Nowadays, building owners, developers, investors, and landlords want to let the world know that their building is special. They want a “diploma” on their building and appreciate the perceived value this brings.

For some in the buildings trade, it’s a point of pride. For most, it’s a business decision. Third-party recognition may help attract tenants who don’t see the sign on a competitor’s building, or it may allow you to charge a premium. Tenants are relying on the same logic and trade-off calculation we all use in everyday decisions. Faced with a choice between two health-care providers, one with a diploma from an accredited medical school and one without, who do you choose, all else being equal? It’s a no-brainer. The same might be said for buildings. Some building owners and some tenants are qualified to look line by line at the performance of water systems, the disposal of construction debris, or the provenance of sustainable timber stock; but most would rather rely on outside authorities to certify that the building passes muster.

This kind of certificate of approval for green buildings has evolved among many forward-thinking tenants, landlords, and investors from a “nice-to-have” to a “baseline must-have.” We expect that in the future the implementation, validation, and communication of some concept of Healthy Buildings will become an even more important differentiator for sophisticated companies.

But—crucially—decisions about Healthy Buildings go far beyond a few incremental and benign design or equipment options. Faulty systems can make people really sick. Accordingly, as Healthy Buildings get more and more scrutiny, we can expect awareness to include not just what the standards and measurements are but also who is doing the certifying—and how deeply they are evaluating the systems and results.

This chapter looks at the recent history and current status of rating and ranking systems. We also talk a bit about the factors that have historically influenced certification practices, since techniques and systems are being rapidly advanced by newer Healthy Building rating systems. Going forward, we anticipate a future that involves extensive sensors, analytics, and real-time reporting. New rating systems will evolve, and we will share some thoughts about the direction things are going.

Our hope is that by the end of this chapter we will have convinced you of the following:

- The green building movement and green building certification offer important insights into the burgeoning Healthy Building movement, but certifying something as “healthy” is very different from certifying something as “green.”

- The first Healthy Building certification systems are a good start for promoting a “people-centric” approach to rating buildings but each have different strengths and weaknesses.

- The capital expenditures and certification costs for Healthy Buildings, while at first glance cost prohibitive, are less so once human performance and health are factored in.

- Who is doing the certifying is as important as what is being certified.

- Expertise (and available tools) will evolve rapidly, and the systems and standards can be expected to be fluid.

Lessons from the Green Building movement

Pioneering efforts in the early 1990s involving architects, designers, equipment manufacturers, and standard-setting organizations started the first conversations about creating green buildings—ones that use materials thoughtfully, are environmentally sensitive, and conserve energy. The concept of a green building is important in its own right, certainly. But it also pioneered a competitive way of benchmarking buildings against some design standards and against each other, an essential innovation that really got the movement to take off. This quickly led others to identify the need to recognize and certify green buildings. Some sort of a “diploma” for buildings was in order.

One of the first major players in the green buildings space was the U.S. Green Building Council (USGBC), which, under the leadership of its founder and first CEO, Rick Fedrizzi, established the most influential green building certification standard, Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design (LEED).1 Soon after the idea of the green building plaque displayed on a wall in the building entryway was born. And just as we have graduation ceremonies for new grads, there are now plaque ceremonies for new buildings.

The LEED concept was highly influential. The early green building acolytes really had no formal standing in the design and construction community, no direct influence on building codes or equipment standards or inspections, and no financial influence. How could they get the things they cared so passionately about onto the radar of the broader community? Most of the industry was cautious and not paying much attention to “going green” at that time. By conceiving, establishing, codifying, and relentlessly promoting a clear, understandable, compelling, and universally applicable rating system, the USGBC eventually influenced the language of local and national building codes; the standards promulgated by bodies like the American Society of Heating, Refrigerating and Air-Conditioning Engineers; zoning and permitting processes in many cities and towns; leasing standards for huge national tenants; and even investment and underwriting decisions by important financial players.

Since the rise of LEED and USGBC, over 100 green building councils have emerged around the world and dozens of green building certification systems have been developed, nearly all of which administer plaques to display on buildings that meet specified criteria—an incredible testament to the success and vision of the movement’s leaders. Green building certification codes all share many common elements, and since LEED paved the way and is still the predominant standard in most places, we’ll talk about LEED here to give you a sense of what these green building rating systems look for and how they work. Much of what we write applies to other green building certification systems too, though the specifics may vary. There are important parallels, as you will soon see—and a few notable differences—with the Healthy Building movement.

Green building ratings are all based on a scoring system. A building team gets “credits” for different strategies that they pursue. For example, LEED will rate your building based on the scores you get for things like water efficiency, energy efficiency, design, and the sustainability of the site. Depending on your total score, the building will then be classified at one of three different levels—LEED Silver, LEED Gold, and LEED Platinum.

One of the major benefits of a certification system is that it offers a common benchmark for consumers and investors. LEED likens its green building points or credits to the information on a food product’s nutrition label, an analogy that we’ve also found very effective.

Much as a nutrition label allows us to compare food products and tells us what’s inside, a good building certification system lets us compare buildings. A LEED Platinum building in New York shouldn’t be too different from a LEED Platinum building in Dubai. (This not 100 percent true, as there are prerequisites that every building has to hit, local parameters and environmental challenges, and optional credits allowing for different pathways to certification.)

This ability to compare buildings across wide geographical locations has had dramatic economic consequences. One key reason for this is that many of the “customers” of these buildings are institutional investors, who typically allocate 5–10 percent of their portfolios to real estate through direct investments or managed funds like limited partnerships or real estate investment trusts. In the last several years, many investors have indicated their preference for green buildings, too. The Global Real Estate Sustainability Benchmark (GRESB) reports that over $7 trillion of global real estate investment is managed by entities who track their green building performance.2

FIGURE 8.1 Example of a building “nutrition label” from the USGBC’s LEED program. U.S. Green Building Council.

One of the main critiques of green building certification systems is that they largely represent the design and performance of a building at one particular point in time. Does the LEED Platinum plaque in an office from 2007 really tell us anything about the performance of that building today, more than a decade later? The answer is largely no. (And we expect this would hold true if any of us were to be tested today on the things we knew at the time we received a college diploma, too.)

Fortunately, just as there has been a movement in education toward “lifelong learning,” there is a corollary in buildings as we seek to move from static determinations to dynamic assessments, where building performance is measured and verified continually. Under the direction of USGBC’s current CEO, Mahesh Ramanujam, it is moving to more dynamic scoring of buildings. (More on the details of measuring and tracking building performance in Chapter 9.)

LEED has had remarkable influence on the market. As of 2019, there were over 8 billion square feet of LEED-certified space globally.3 One of the drivers of this success is the promised financial return on investment through energy savings. LEED buildings save around 20 to 40 percent of energy use intensity when compared with their noncertified counterparts.4 This translates into bottom-line operating savings for the business—savings, as we illustrated in the pro forma tables in Chapter 4, that have the really nice feature of being very easy to estimate, measure, and verify. Energy savings are a line item in the operating budget that everyone can understand. Some building owners and users have the internal capability to do sophisticated cost-benefit analyses of engineering investments, particularly in energy efficiency. Some of those bristle at the relative simplicity and lack of financial analysis in LEED-certified building. But for the most part, the points system has been remarkably effective at moving the industry in a green direction.

Today in some markets, such as New York City and San Francisco, green building is now business as usual. If your new commercial building is not LEED certified, this will often raise red flags. Part of this comes from market forces (“If my competitor is doing it, I had better do it, too”). Part of it is a new set of expectations (tenants now look for the LEED plaque and investors want to see it, too). And partly it is driven by local government. (New York announced in 2019, as part of its Climate Mobilization Act, that it was mandating that buildings reduce carbon emissions by 40 percent by 2030 and 80 percent by 2050.)

LEED is not in itself a building code or ANSI-approved national standard. It’s not a measure of realized performance, nor does it come with a detailed cost-benefit analysis. Even so, USGBC and LEED have driven designers to design more creatively, builders to build better, manufacturers to innovate, and developers to develop more sustainable buildings by almost any measure. What might be next, now that the public and the market have both grown accustomed to certifications and awareness of the human and financial cost of sick buildings is growing?

Healthy Building Certifications

It probably won’t come as a surprise to you to hear that with the rise of the Healthy Building movement, there has been a corresponding push for Healthy Building certification systems to replace, compete with, or complement green building certifications. (The distinction depends on whom you talk to, and how they view these new certifications.) Several certification systems have an early lead to fill this gap. Let’s briefly review these early contenders, not so much to endorse or criticize them but rather to give you an understanding of how this is playing out in the market, and how we think it should be playing out. Broadly, we think things are changing fast in terms of current market awareness, with some key participants shifting from viewing such certifications as a nice-to-have to viewing them as a must-have. Some key participants are also reporting “certification fatigue.” They want to do what’s best for their building and the people in it, but don’t want to go through a certification process or pay the certification fees. We are confident that there are substantial high-impact benefits to be unlocked by new technologies and enhanced “smart building” capabilities and this shift to Healthy Buildings, with or without certification.

Early Days: Good Science, Poorly Disseminated

The Healthy Buildings movement has existed for decades, really, but it was first led by scientists who largely mobilized around the theme of “indoor air.” Early research on indoor air quality spawned scientific organizations like the International Society of Indoor Air Quality and the academic journal Indoor Air (for which Joe is an associate editor). Most scientists are not businesspeople, few are skilled communicators, and even fewer have access to decision makers in the real estate industry. The result is that much of this compelling evidence on healthy indoor air remained bottled up, so to speak, in academic journals and conferences that failed to penetrate the market that these scientists were ultimately trying to influence—the people who design, operate, maintain, and certify buildings.

Joe was struck by the depth of this problem at a meeting of the Real Estate Roundtable in 2016, when he said, “We’re overcomplicating what it means to have a Healthy Building. There are only a handful of things we need to control, and everyone knows what they are.” At which point the entire room leaned in and began asking questions that would be considered basic by the “indoor air” crowd. This drove home the fact that the body of rich scientific evidence had yet to be leveraged by practitioners.

Three things were becoming very clear: (1) there was a gap between research scientists and practitioners, (2) there was a demand for Healthy Building knowledge and services being voiced by the market, and (3) someone was going to fill that demand. Thus, the rise of Healthy Building certifications.

The WELL Building Standard

The WELL Building Standard was created by Paul and Pete Scialla, two brothers with experience in the finance world, who recognized the immense potential of combining two of the largest sectors in the US economy—real estate and health care. What the Scialla brothers lacked in formal training in health they made up for in experience in the business world. They saw a market opening up and launched Delos, a health and wellness company, and founded the International Well Building Institute (IWBI), the arm of their company that created WELL.

On the marketing front, the Scialla brothers and their team were quickly able to achieve impressive results. Rather than compete outright with existing green building certification standards, they teamed up with USGBC and began sponsoring the main conference on green buildings, Greenbuild, which is attended by between 10,000 and 20,000 people each year. This created a seemingly seamless connection between LEED and their rating system, WELL.

WELL was first released in 2014 and within a matter of months, the entire global real estate market seemed to be talking about it. Wherever we have traveled around the world, someone has inevitably asked us about the WELL Building Standard—a credit to both the rise of the Healthy Buildings movement and the communication and marketing skills of the team at IWBI.

WELL’s splashy launch helped socialize the different elements of a Healthy Building. Suddenly people in the green building world began to understand that they should be looking beyond the green building’s indoor air quality standard—or what we consider “IAQ 101”—by putting quantifiable targets on new things like lighting, noise, and ventilation. In short, WELL got people in the green building certification world to start thinking about prioritizing health.

Like all measurement and incentive systems, WELL was susceptible to efforts to game the rating system. This mirrored the experience of LEED, where skeptics will point to the oft-maligned “bike rack credit”—a meaningful addition for some buildings but a “check the box” credit for the many suburban office parks surrounded by giant parking lots and road networks that don’t support biking. So the building gets a LEED credit for encouraging energy-reducing behaviors like biking, but in reality it would have been better off focusing on actual energy-conserving measures.

For WELL, this “gaming” could be seen with visible category signaling, as artifacts and devices were placed in a prominent space as part of a hunt for less expensive points. This led to no end of grousing as some scoffed that the next thing you know, you’d see companies placing a bowl of nuts next to a treadmill in the main lobby area of a WELL Platinum building so the company could get credits for both nutrition and movement.

But WELL continued to evolve. In 2017 IWBI recruited the principal architect of the green building movement, Rick Fedrizzi, to become CEO. Rick quickly brought on several key players from USGBC, including the former director of USGBC’s Center for Green Schools, Rachel Gutter, who is now the president at WELL. This further strengthened WELL’s ties to the established green building movement and brought in an experienced team to deliver the second version of WELL. (For several years, a few of these executives were on the advisory board of a center at Harvard that Joe was a part of, and Joe was on the advisory board for the Center for Green Schools at USGBC. Joe has not formally worked with them since they moved over to WELL.)

WELL v2, released in 2018, addressed many of the issues that had impeded the success of the initial launch. For starters, the certification price came down by a factor of 10. Many features were now less confusing and more streamlined. The company also introduced pricing strategies and discounts that supported the adoption of WELL in developing countries, and a portfolio option so large companies wouldn’t have to certify their buildings one by one. IWBI installed an advisory board with a few top-notch scientists and hired several scientists with master’s degrees in public health and other related health fields. All solid moves in our view.

In many ways, v2 is a public health win. Its “features” cover many of the factors of the 9 Foundations of a Healthy Building that we discussed in Chapter 6, but WELL went with these 10: air, water, light, movement, thermal comfort, sound, materials, mind, community, and nourishment. The entry of executives, business leaders, and investors from the green building certification world into the Healthy Building world was a good signal for those who wanted to see the Healthy Buildings profile raised. These green building and business leaders had the skills necessary to bring Healthy Buildings to the masses, and they had the wherewithal, as all good leaders do, to bring in experts in areas where they did not have expertise, leveraging the science and bridging the gap to drive research into practice.

Fitwel

Fitwel, another certification system that is gaining prominence, was created as a joint initiative between the leading institutions in the US federal government that focus on health and on buildings: the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the General Services Administration, the federal agency responsible for managing all government buildings. They eventually spun out the Fitwel program and it is now being administered and managed by a nonprofit, the Center for Active Design. And Fitwel is getting traction: Tishman Speyer, a leading company in the commercial real estate space, announced in 2017 that it was going to deploy the Fitwel certification across its global portfolio.5 In 2019, Boston Properties rolled it out across 11 million square feet of class A office space.

Like WELL, Fitwel aims to promote healthier indoor environments. But the two certification systems differ in important ways. First and foremost, Fitwel is a self-administered checklist. Essentially, the building representative surveys a new or existing building and looks for things that satisfy Fitwel’s list of health-promoting items.

Some of these things are uncontroversial common sense, such as verifying that every building has an automatic defibrillator and ensuring that asbestos is managed properly. Some are potentially open to gaming (“Adopt and implement an indoor air quality policy” and “Provide access to sufficient active workstations”). Some are dictated by code (“Provide at least one ADA compliant water supply on relevant floors”). Some of it isn’t really tied to health, per se (“Provide at least one publicly accessible use on the ground floor”).

Perhaps the most important difference between WELL and Fitwel (certainly the one most noticed by the market) is that Fitwel only costs a few thousand dollars per building to administer, while WELL can run up to hundreds of thousands of dollars for a large project. This makes it attractive to the market, and this aspect allows someone like Tishman Speyer to consider rolling it out to over 2,000 tenants in over 400 real estate assets covering 167 million square feet across four continents.

But an important question remains. The few thousand dollars required for Fitwel makes it an attractive alternative because it’s enough to get a building owner a plaque out front signaling that this is a “Healthy Building.” But does this self-administered checklist really mean that Fitwel buildings are demonstrably healthier buildings? This remains an open question. Some of the points or credits in the Fitwel rating system are quite subjective, opening up different interpretations for everyone involved. For example, if a building has a Fitwel credit for having an indoor air quality plan, the devil is in the details. Such a plan could be a one-page “plan” that says something basic like “monitor carbon dioxide on each floor,” or it could be an exhaustive blueprint for monitoring all of the 9 Foundations of a Healthy Building.6 And for the market, how do you compare these two buildings, both of which might have received Fitwel certification?

The counterargument, naturally, is that Fitwel is a good first step. It signals that the owner is thinking about health. That’s an important start.

RESET and LEED

There is certainly good news here. It is undeniable that the market is migrating toward a desire for truly Healthy Buildings, and that it is looking for solutions, including some means of ascertaining that the asset in question is objectively healthy. This suggests that designers and building owners will also be seeking more comprehensive information to support their decisions.

As of this writing, many other players are jumping into the certification or rating-system game. RESET, a standard first developed in China, falls somewhere between Fitwel and WELL in terms of cost and rigor (closer to WELL).7 RESET is interesting to us because it approaches the assessment of Healthy Buildings from a technology and performance standpoint. The method avoids checklists and prescribed paths, opting instead to focus on results: if your building meets some performance standard with regard to indoor air quality, they don’t care what path you took to get there. The RESET certification relies on the rise of new technologies that allow for the continuous measurement of indicators of indoor air quality, such as CO2, particles, and temperature and humidity. The downside to RESET is that it does not currently cover any of the other 9 Foundations of a Healthy Building, or any of the other air-quality factors that cannot be measured with real-time monitors (we will discuss those in Chapter 9). Still, RESET is clearly positioned for a smart building future where more and more of the 9 Foundations will be able to be measured reliably in real time. One can predict that other Healthy Building certification systems will have a similar focus on real-time performance verification in the near future.

LEED, the original green building standard-bearer (primarily focused on energy, waste, and water for many years) is also expanding its reach into the Healthy Building space, spending a lot more time talking about “health and human performance”—up until now a second-tier consideration. The latest version of LEED dedicates approximately 15 percent of its credits to indoor environmental quality, which may not seem like a high percentage at first glance, but when you explore the specifics under this category, you see that LEED is looking at a lot of the same factors as the other rating systems: acoustics, lighting, controlling tobacco smoke, and taking into account certain factors like controlling emissions of volatile organic compounds from products and testing the indoor air quality for those compounds, PM2.5, and formaldehyde.

All three systems have their benefits and drawbacks. We’re less interested in who will become the dominant player in this space (we actually think there is room and a need for all of them, and more), and more interested in understanding how this Healthy Building movement can scale. This brings us to the perceived barriers to adoption, most notably, cost.

The Cost of Certifying a Healthy Building

Let’s look more closely at the costs of certification. Securing a WELL v2 certification involves several layers of costs. These include registration, certification, and on-site performance verification; substantial capital costs (called CapEx, for capital expenditures) may also be needed to meet the certification standards.

To put some numbers to this, we took the pricing structure on the WELL website as accessed in 2019 and applied it to two different building types: a 100,000-square-foot (sq. ft.) and a 1,000,000 sq. ft. building. We concluded that the costs to obtain this certification would be in the tens of thousands to several hundreds of thousands of dollars, respectively.8 (Pricing rates and structures for WELL and other certifications can change rapidly, and may vary based on the unique characteristics of each building).

Costs for any additional CapEx and the required “on-site performance verification” are not included in the WELL certification costs, so we used a few different sources to estimate these values. For the additional capital cost estimates, we relied on a report by the Urban Land Institute that examined lessons from early adopters of the WELL Building standard.9 ULI conducted interviews with several owners and developers of WELL projects, who pointed to the “hidden” capital costs necessary to improve the building in order to achieve the certification, which ULI reports as $1–$4 per square foot. They also cite one example, the WELL-certified CBRE Headquarters in Los Angeles, where additional capital costs were reported as a 5 percent increase in overall price. (Another WELL-certified building, in Toronto, lists its increase in capital costs for this purpose at 15 percent.)

|

TABLE 8.1 Example costs to receive WELL certification for two differently sized buildings. |

||||||||

|

EXAMPLE 1: 100,000 SQ. FT. BUILDING |

EXAMPLE 2: 1,000,000 SQ. FT. BUILDING |

|||||||

|

Price per square foot |

Total price |

Price per square foot |

Total price |

|||||

|

Precertification (optional) |

$0.02 / sq. ft. |

$2,000 |

$0.02 / sq. ft. |

$20,000 |

||||

|

Registration Fee |

$0.028 / sq. ft.* |

$2,800 |

$0.0042 / sq. ft.* |

$4,200 |

||||

|

Certification |

$0.175 / sq. ft. |

$17,500 |

$0.145 / sq. ft. |

$145,000 |

||||

|

On-site Performance Verification† |

$0.08 / sq. ft.– $0.48 / sq. ft. |

$8,000– $48,000 |

$0.08 / sq. ft.– $0.48 / sq. ft. |

$80,000– $480,000 |

||||

|

Estimated Process Subtotal |

$0.30 / sq. ft.– $0.70 / sq. ft. |

$30,300– $70,300 |

$0.25 / sq. ft.– $0.65 / sq. ft. |

$249,200– $649,000 |

||||

|

Estimated additional capital costs to meet certification |

$1 / sq. ft.– $4 / sq. ft. |

$100,000– $400,000 |

$1 / sq. ft.– $4 / sq. ft. |

$1,000,000– $4,000,000 |

||||

|

TOTAL |

$130,300– $470,300 |

$1,249,200– $4,649,200 |

||||||

|

*The registration fee is a flat rate of $2,800 for buildings between 50,000 and 249,999 sq. ft. and $4,200 for buildings between 500,000 and 1,000,000 sq. ft. We normalized this to a cost per square foot for this hypothetical 100,000 or 1,000,000 sq. ft. building. |

||||||||

|

†On-site performance verification is required to achieve certification but is administered by third parties; fees for this testing are not listed in the WELL certification pricing. Our cost estimates are derived from: 1) the ULI report referenced in this section, which reported a combined certification + performance verification costs of $0.18–$0.58 / sq. ft., and 2) our own research in compiling an equivalent test protocol using consultants, monitoring equipment, and outside laboratories. |

||||||||

Are Healthy Building Certifications Cost Prohibitive?

You are probably thinking this seems expensive. As with many “health” upgrades to a building, the costs often represent a barrier to adoption—in our view this is a shortsighted barrier. In our interviews with real estate leaders, cost was one of the main concerns. But health insurance can chew up to 25 percent of annual payroll expenditures if you consider the “fully loaded” cost including taxes and benefits. And think of the money we spend on nutrition, exercise, or vitamins—or the premium many of us pay for “healthy” food every day. If we are personally willing to spend so much of our hard-earned cash on a whole host of things that will make us healthier, why, when it comes to buildings, are we so afraid to spend on health?

The answer is that the known costs are deemed too great for what are perceived to be uncertain benefits (that and the issue of split incentives, which we will get back to shortly). These expenditures are shunted aside as a boring cost center without any perceived operational, revenue, performance, or reputational gain. That common assessment is what we are trying to challenge with this book.

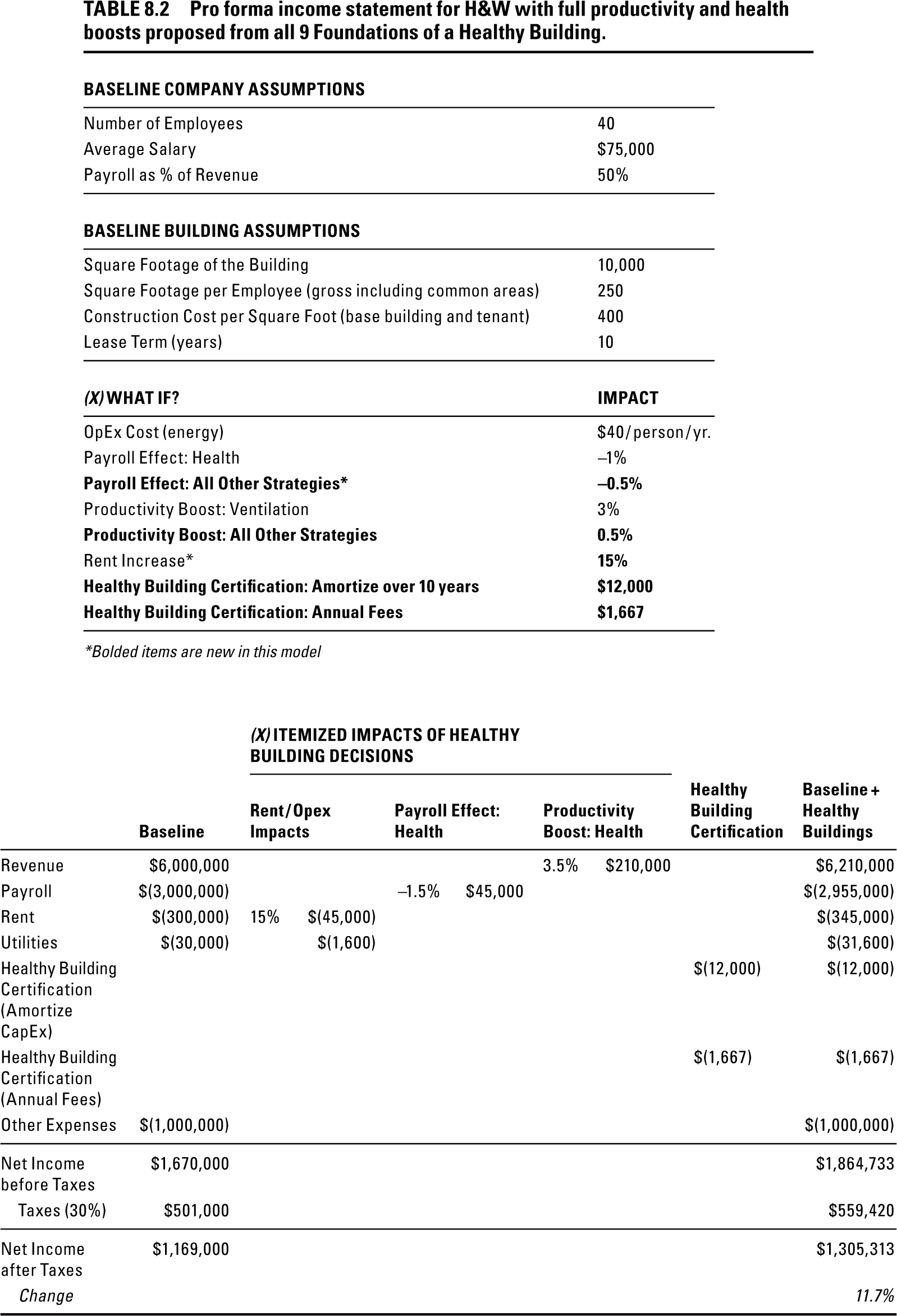

It’s not the case that a building has to be certified in order to be a Healthy Building; but for our purposes here, let’s add in the cost of a Healthy Building certification to the cost-benefit analysis in our pro forma from Chapter 4.

It’s worth noting at this point that we are entering the realm of forward-looking real estate finance projections and departing the domain of empirical measurement of science experiments. For all but the most routine infrastructure and real estate projects, financial projections are relied on to organize assumptions and understand possible future outcomes. Developers must make numerous decisions under conditions of high uncertainty. Generally, they examine ranges of possible long-term results in order to make both the primary “go or no go” building decision and hundreds of incremental choices about individual components of the building that will never have directly traceable revenue or cost linkages. For example: How much should be spent on windows, on carpets, on kitchen counters and cabinets, on the pool or the gym, or on the parking—or the ventilation system? For many developers, this is an art that comes down to experience and intuition around the aggregate appeal of all aspects of the product, and what the market might pay.

The classic example is a new apartment building that might range from $150 to $200 per square foot to build, where the rental rates upon completion and stabilization might be $1,500–$2,500 per month for a two-bedroom unit, and interest costs might range from 4 percent to 6 percent per year. At the time of the initial commitment to the project, all of these are unknown and most of them will be revealed many years in the future. Here’s how this plays out, in very round numbers: If a two-bedroom unit is 1,000 sq. ft., then at $150 / sq. ft. it costs $150,000 to build. If the rent is $2,000 per month, then that’s $24,000 per year; $24,000 / $150,000 = 6.67 percent cash-on-cost yield. If the developer can borrow at 5 percent (an interest rate that is less than the yield), then the project “pencils in” favorably on a back-of-envelope basis; the annual cash flow will work and the developer will make money. But at $200 / sq. ft. cost, that becomes $200,000 to build. If the building doesn’t perform as well as expected and is only able to command rent of $1,500 / month when the building opens three years from the start of construction, that’s $18,000 per year, or only 3.6 percent cash-on-cost yield. If interest rates at completion and permanent financing have jumped to 6 percent, then the promoters will lose money—the cash flow won’t even cover the interest cost—and the developers should not have started the apartment building project.

Real estate people focus on two aspects of analysis. First, how closely can our assumptions be based on comparables in the market today? Current rental rates and historic construction costs can be approximated if there is good access to information from other firms. Then the questions become, “Is the number truly comparable to the number for this other design?” and “What changes do we think will happen in the market during construction?” The second aspect involves sensitivity testing (for banks, stress testing). A typical sensitivity test would be something like this for a developer: “All else being equal, how low can occupancy rates fall for us to still realize positive cash flow?” Or for a bank, “How far can market yields rise for us to still have complying loan-to-value ratios?”

Both parties are trying to find the boundaries of a successful deal. This degree of uncertainty is unsettling for empiricists, since the data is really not out there at decision time. But it’s second nature for project developers ranging from dam builders to tract housing promoters to big-city office building developers. The following sections use “what if” examples to determine the boundaries of what has to unfold for these decisions to make sense. We explain our rationale for the figures, and readers are encouraged to consider impacts and draw their own conclusions if their underlying assumptions or market expectations are different from the ones modeled here.

With that understanding about how cost-benefit calculations work in real estate, let’s get back to our opening question in this section: Are Healthy Building certifications cost prohibitive in the big picture? For discussion purposes, let’s assume that an office building design calls for about 250 sq. ft. per employee. (Your office probably isn’t 16 × 16 feet; that figure also includes an allocation for common areas like lobbies, conference rooms, and washrooms.) We’ll assume that this building’s construction cost is $400 / sq. ft. for the base building and the tenant fit-out work, a number that would be in the ballpark for a suburban office building but low for New York City or San Francisco. If the capital cost upcharge to include all of the incremental labor and materials that result in a certifiably Healthy Building is taken to be 3 percent (a middle figure from the costs just discussed), that’s about an additional $12 per square foot, or $3,000 per person for each person’s allocated 250 sq. ft. of space.

Let’s now return to our financial model for Healthy Buildings Inc. (HB) and factor in the new anticipated CapEx for building a Healthy Building and getting the building certified. On the capital expenditure side, the $3,000 per person cost we just estimated sounds like a lot—until you consider that it’s a one-time cost. Assuming a typical office lease of 10 years, and assuming that 100 percent of the cost is absorbed by the tenant company, that works out to $300 per person per year. With respect to the 40 employees of HB, it’s a cost to the company of $12,000 per year in total. On the benefits side, as a reminder, in Chapter 4 we showed how improving ventilation could lead to a 3 percent productivity boost from health and a 1 percent payroll effect. You’ll see those numbers in the same spot here on the left-hand side of the model. Now, let’s factor in an estimate of all of the other benefits of the 9 Foundations of a Healthy Building, which also show up in Healthy Building certification systems (for example, light, noise, allergens in dust, and water quality). These benefits are in addition to the ventilation and filtration discussed in Chapter 3. Let’s assume, conservatively, that collectively they improve the company’s revenue and payroll performance by half of one percent each. We feel comfortable making this assumption based on the science we presented in Chapter 6—findings like higher throughput at optimal temperatures, how lighting conditions affect mood and concentration, and real-world examples of poor building maintenance shutting down work altogether. The numbers follow.

With all of these assumptions, using the same figures we have been carrying throughout the book, this company’s projected bottom line (net income after taxes) improves from the original $1,169,000 to $1,305,313 here—a nearly 12 percent improvement.

Is this plausible, or just fantasy? We maintain that impacts on this order of magnitude are real and should be considered. From a decision-making point of view, there is a significant financial improvement, plus people are healthier, happier, and more creative. And remember, this model includes the CapEx that often give owners pause when they start considering building to a Healthy Building standard, as well as the associated costs.

|

TABLE 8.2 Pro forma income statement for H&W with full productivity and health boosts proposed from all 9 Foundations of a Healthy Building. |

|||

|

BASELINE COMPANY ASSUMPTIONS |

|||

|

Number of Employees |

40 |

||

|

Average Salary |

$75,000 |

||

|

Payroll as % of Revenue |

50% |

||

|

BASELINE BUILDING ASSUMPTIONS |

|||

|

Square Footage of the Building |

10,000 |

||

|

Square Footage per Employee (gross including common areas) |

250 |

||

|

Construction Cost per Square Foot (base building and tenant) |

400 |

||

|

Lease Term (years) |

10 |

||

|

(X) WHAT IF? |

IMPACT |

||

|

OpEx Cost (energy) |

$40 / person / yr. |

||

|

Payroll Effect: Health |

−1% |

||

|

Payroll Effect: All Other Strategies* |

−0.5% |

||

|

Productivity Boost: Ventilation |

3% |

||

|

Productivity Boost: All Other Strategies |

0.5% |

||

|

Rent Increase* |

15% |

||

|

Healthy Building Certification: Amortize over 10 years |

$12,000 |

||

|

Healthy Building Certification: Annual Fees |

$1,667 |

||

|

*Bolded items are new in this model |

|||

|

(X) ITEMIZED IMPACTS OF HEALTHY BUILDING DECISIONS |

||||||||||||||||||

|

Baseline |

Rent / Opex Impacts |

Payroll Effect: Health |

Productivity Boost: Health |

Healthy Building Certification |

Baseline + Healthy Buildings |

|||||||||||||

|

Revenue |

$6,000,000 |

3.5% |

$210,000 |

$6,210,000 |

||||||||||||||

|

Payroll |

$(3,000,000) |

−1.5% |

$45,000 |

$(2,955,000) |

||||||||||||||

|

Rent |

$(300,000) |

15% |

$(45,000) |

$(345,000) |

||||||||||||||

|

Utilities |

$(30,000) |

$(1,600) |

$(31,600) |

|||||||||||||||

|

Healthy Building Certification (Amortize CapEx) |

$(12,000) |

$(12,000) |

||||||||||||||||

|

Healthy Building Certification (Annual Fees) |

$(1,667) |

$(1,667) |

||||||||||||||||

|

Other Expenses |

$(1,000,000) |

$(1,000,000) |

||||||||||||||||

|

Net Income before Taxes |

$1,670,000 |

$1,864,733 |

||||||||||||||||

|

Taxes (30%) |

$501,000 |

$559,420 |

||||||||||||||||

|

Net Income after Taxes |

$1,169,000 |

$1,305,313 |

||||||||||||||||

|

Change |

11.7% |

|||||||||||||||||

Even with this broad brush, you can see that the costs of the certification process are trivial in the context of the whole project. When a number of less than $12 per square foot is considered in the context of $400 per square foot of construction costs, it can be absorbed quickly. If one amortizes the $12 per square foot over the ten-year cycle, and think about it on a per-employee basis, that’s $300 per year per employee. This is about the price of one cup of fancy coffee each week!

Split Incentives?

You may be thinking this is a naïve analysis for the simple reason that, with the exception of owner-occupied buildings, the costs and benefits are not incurred by and going to the same company. The building owner and developer pay the additional CapEx and certification costs, while the tenant gets the benefit in employee productivity and health. The cost-benefit incentives are not aligned.

If you were thinking along those lines, take another look at the pro forma. You’ll see that the rent premium is now modeled at 15 percent—and the company is still better off than the baseline. The landlord may not be able to capture all of this benefit in additional rent—the tenant might be a better negotiator and could retain more of the marginal value for itself (or share it with employees)—but the numbers show that there is a lot of value to be created that can then be shared. We chose a 15 percent rent premium to highlight the magnitude of value created, not to suggest that the lease agreement might contain this sort of language. Everyone can win. The landlord gets a rent premium, the tenant gets a productivity boost, and the employees are healthier.

A Tower for the People: 425 Park Avenue

Moving beyond this hypothetical, let’s explore the financial implications of decision-making around Healthy Buildings certification in an actual building, We did this recently for our joint Harvard Business School / Harvard T. H. Chan School of Public Health case study about 425 Park Avenue in New York City (“A Tower for the People,” written with Joe’s doctoral student Emily Jones).10

In the words of David Levinson, chairman and CEO of L&L Holding, the project’s developer, 425 Park Avenue is “the first new office building on Park Ave in New York City in 50 years.”11 Levinson selected none other than Norman Foster of Foster + Partners to design the new building to replace a building constructed in the 1950s. They shared a grand vision for the new space. In Foster’s words, “Our aim is to create an exceptional building, both of its time and timeless, as well as being respectful of its context and celebrated Modernist neighbors—a tower that is for the City and for the people that will work in it, setting a new standard for office design and providing an enduring landmark that befits its world-famous location.”12

Levinson has a long history of acting ahead of the curve with respect to design innovation. He told us that he makes decisions based on his intuition from decades of experience in the industry (and, no doubt, plenty of sophisticated research).13 His intuition on 425 Park Avenue? That health will be the differentiator for his tower, which will be the first WELL-certified commercial office building in Manhattan.

Perhaps the most interesting take-home from our conversations was this: Levinson is not just thinking about what his tenants will want this year or next. He is thinking about the tenants 5, 10, and 20 years from now. His major concern is that if he doesn’t take these steps toward health now, his building will be outdated in a few short years, surpassed by the next “latest and greatest” building. In some ways, it’s a risk-management decision. He is future-proofing his building.

In our case study we look at decisions in the design phase, before the building was built. (Since this is the first commercial building pursuing WELL certification in New York City and these are the early days of landlord awareness, at this writing there are no finished, rented, stabilized examples of this degree of attention to occupant health and indoor air quality.) During the design phase, the financial projections are just that—projections. We walked through many of the decisions made by Levinson and his team, including decisions about ventilation, filtration, and whether to pursue WELL certification. For our purposes, here we are just going to cover the economics of pursuing a Healthy Building certification.

The building at 425 Park Avenue has approximately 675,000 square feet of gross leasable area across 47 floors. The average asking rent is $150 per square foot per year on a triple net lease basis. (This is a common office lease arrangement where the tenant is responsible for its own operating expenses and an allocation of property taxes and building expenses; effectively, the gross rent for the building is in excess of $200 / sq. ft.) The $150 / sq. ft. / year is an average for the building, but as you would expect, the rent on the top floor is higher than for lower floors, so we built multipliers into the model to account for that. The cost to construct this building in the heart of Midtown Manhattan is about $750 / sq. ft., not including land.

We combined all of this in order to estimate net operating income over development cost, a standard ratio for evaluating the expected economic performance of a new real estate development. We then repeated the analysis but added in a 3 percent construction cost premium for achieving the WELL certification as estimated by the L&L team, and a 2 percent rent multiplier to illustrate the general impacts.

In baseline projections, the development cost is about $1.2 billion and the annual net operating income is anticipated to be about $72 million, penciling out to a yield of about 6 percent as a percentage of original project cost, year after year. (This is in range for new office developments in New York City.) Many other factors go into assessing returns on building projects, with key aspects being bank loans, any partnerships in the equity portion of the project, and assumptions about value at refinancing or sale; we don’t go into this here, but they are the foundation of John’s real estate courses at Harvard Business School.

In this model, Levinson and L&L receive an extra $1.5 million per year in net operating income (that is, cash flow from operations) and the cash-on-cost yield improves by about 25 basis points. The upcharge in initial costs is clearly worth it if the achievable rent also increases along these lines. The market, investment, and cost strategy approach includes three aspects to consider from the point of view of the developer and architect planning the project: (1) Does a Healthy Building strategy increase the likelihood of a fully occupied building? (2) Will the landlord be able to realize a material rent premium today for a certifiably Healthy Building? and (3) Will trends in the market mean that rents rise faster in a building with these characteristics than they will in other, less healthy buildings?

Levinson believes he needs to have this Healthy Building differentiator if he is to attract tenants and command the $150 / sq. ft. per year net rent. What if the added construction costs for a Healthy Building are the difference between a fully occupied building and one that is not? The financial implications are stark—if 425 Park Avenue falls to 95 percent occupied, the yield drops below 6 percent, with about a $3 million revenue hit. It could be that the Healthy Building investment defends the building against vacancy in the event of a downturn.

For questions 2 and 3, there are opportunities for Levinson and L&L to charge a greater rental premium for this building. Now, what if Levinson were able to realize a 5 percent rent premium instead of 2 percent, based on the health benefits to tenant employees? This would amount to an additional $3 million per year in revenue. That’s a big deal. And remember, in the earlier portions of this book we argue that tenants are making a better business decision if they are willing to pay a little more for a space that demonstrably gives people a chance to be more productive and effective. The incentive structures are in place for Levinson to charge a premium, and a shrewd tenant should be willing to pay it.

Levinson recognizes the significance of these three strategic aspects. In fact, it’s an explicit part of L&L’s billion-dollar bet. In his words, “In an up market, I get the premium. In a down market, I get the tenant.”14

What If You Get It Wrong? The Case for Expertise

One major concern with the burgeoning Healthy Building movement is this: if a LEED professional screws up the water or energy analysis for a green building certification, it’s bad, but no one dies. If a WELL professional screws up, he or she is potentially jeopardizing the health of everyone in the building. Putting the world “health” in a business equation draws positive attention, but it also comes with great responsibility. A short aside here is worthwhile because it highlights the potential moral and legal perils of unconstrained enthusiasm about representing what’s in a Healthy Building.

The aside: Elizabeth Holmes was the self-made billionaire founder and CEO of Theranos, a company that promised to replace the venous-draw approach to human blood testing with a simple pinprick test. This would be truly revolutionary, had it worked. But it didn’t. The entire company was a fraud that was ultimately exposed by the Wall Street Journal reporter John Carreyrou and immortalized in his book, Bad Blood.15

As detailed by Carreyrou, Theranos knowingly rolled out a faulty blood-testing service in the drugstore chain Walgreens and began reporting incorrect lab results to patients. One woman, who is now suing Theranos, was incorrectly diagnosed with a thyroid disorder that resulted in her being put on medication she didn’t need. Another was a heart surgery patient who received faulty results from Theranos and then switched his medication and underwent what he claims were unnecessary follow-up procedures. These are not two isolated incidents, either; over 1 million lab tests from Theranos had to be voided or corrected.

Here’s the relevance to buildings. Holmes was simply doing what others in Silicon Valley had done before—she initially delivered imperfect products, confident that her company would eventually iterate and ultimately get it right. The problem is that, unlike a software company, which can deliver imperfect first-launch software supplemented by periodic fixes or patches, Theranos was playing with people’s lives. It wasn’t selling software; it was selling health. So when the firm got it wrong, people’s lives were at stake. As of the writing of this book, Holmes has been indicted on fraud charges, because her “getting it wrong” was not an accident; it was willful misconduct, as alleged and documented in the indictment.

The same cautionary tale should be heeded with Healthy Building rating systems. With Healthy Buildings, a mistake here, or a promise of a Healthy Building not based on sound science, is ultimately about health and people’s lives. In the end, perhaps our biggest concern with the current Healthy Building rating systems is not just what the standard is but also who is doing the certifying. And what the implications are if they get it wrong.

When you need your building designed, you hire an architect. When you need a building permit, you hire a professional engineer to sign off on the plans. When you sign a contract, you hire a lawyer to review it. All of these professions have intense qualification protocols. When it comes to certifying the health of your building, it stands to reason that you should hire someone qualified with expertise on indoor health.

Following the lead of LEED, which uses accredited professionals (APs) to evaluate and certify buildings, current Healthy Building systems are also using APs. APs are critical to the success of these certification systems. They offer guidance and strategic support on how to navigate the various rating systems, and they often interface with the architects and design teams to ensure buildings attain their desired status (for example, LEED Silver, Gold, or Platinum).

WELL has the WELL AP, RESET has the RESET AP, and Fitwel does the same thing but calls them Fitwel Ambassadors. This approach—training and accrediting to a common standard—has been crucial in changing the industry, and the world, by engaging hundreds of thousands of people in the building sector and giving them ownership, and opportunities, around certifications. There are already hundreds of thousands of APs who essentially act as brand ambassadors for LEED, WELL, Fitwel, and others.

Yet as much as these APs are essential, another type of expert is also needed—people with deep knowledge of how to measure, monitor, and interpret environmental data in buildings. WELL has started to move in this direction by outsourcing the performance verification of WELL buildings to “WELL Performance Testing Agents” in an approved “WELL Performance Testing Organization.” The requirement to become a testing agent is different from that to become an AP—two days of training hosted by WELL.

That’s a good start, but here we make a strong recommendation: that the Healthy Building movement engage with the community of Certified Industrial Hygienists (CIHs). The CIH certification, now 40 years old, is administered by the American Industrial Hygiene Association. The term “industrial hygiene” is still widely used in the trade, but Joe hates it. Who wants to be an industrial hygienist? It sounds like a dental assistant who works on an oil rig. So we prefer to use the shorthand CIH, and we like to think of it as “Certified Indoor Health,” because that’s actually what a CIH does.

Why CIHs? These are experts at anticipating, evaluating, managing, and controlling hazards for workers. In addition to four years of coursework in the sciences (and oftentimes another two in a master’s program), the classroom training must be followed by five years of work experience under the mentorship of a seasoned professional. Industrial hygiene does not have to be confined to food processing, factories, refineries, and hospitals. These skills matter in every occupied space, including commercial office space.

Now take a look at the type of skill sets they are required to have—and the intensity of the certification exam—and you’ll quickly see that this is the exact type of expertise needed if you really want to understand what’s happening in buildings.

BOX 8.1 Certified Industrial Hygienists

Required Education: bachelor’s degree in biology, chemistry, engineering, or physics

Required Experience: five years plus professional references

Examination Rubrics:

- Air Sampling and Instrumentation

- Analytical Chemistry

- Basic Science

- Biohazards

- Biostatistics and Epidemiology

- Community Exposure

- Engineering Controls and Ventilation

- Health Risk Analysis and Hazard Communication

- Industrial Hygiene Program Management

- Noise

- Nonengineering Controls

- Radiation / Nonionizing

- Thermal Stressors

- Toxicology

- Work Environments and Industrial Processes

Sample Examination Questions:

- Air Sampling. The limit of quantitation for a particular sampling method is 9.3 μg / sample. An industrial hygienist wants to conduct a personal exposure monitoring study with a target concentration of ≥ An of the TLV. The TLV of the substance at issue is 0.1 ppm and the gram molecular weight of the substance is 30.031 g / mol. The proscribed flow-rate for sample collection on an adsorbent tube is 0.050 LPM. How many minutes of sample collection at the proscribed flow rate are required to collect a quantifiable sample result, assuming the concentration is at least 10% of the TLV?

- Analytical Chemistry. An air sampling procedure is accurate within ±16%, and the analytical procedure is accurate within ±9%. What is the accuracy of the total analysis? 16.7%, 17.6%, 14.8%, or 18.4%.

- Basic Science. A mixture contains: 50 mL benzene (m.w. = 78; v.p. = 75mmHG; sp. gr. = 0.879), 25 mL carbon tetrachloride (m.w. = 154; v.p. = 91mmHG; sp. gr. = 1.595), and 25 mL trichloroethylene (m.w. = 131.5; v.p. = 58mmHG; sp. Gr. = 1.45g). Assuming Raoult’s Law is obeyed, what will be the concentration of benzene in air at 760 mmHG saturated with vapor of the above mixture?

- Biohazards. Which fungal type is inappropriate for detection with spore traps and microscopy? Alternaria spp., Stachybotrys chartarum, Aspergillus fumigatus, or Basidiospores.

- Biostatistics and Epidemiology. An industrial hygienist has the following exposure data from a similarly exposed group of employees. The occupational exposure limit for the substance is 100 ppm. The IH wants to ensure the average exposure is less than 10% of the exposure limit. What is the 95% upper confidence limit of the average exposure from this group?

- Risk Assessment. Which of the following would be considered an acceptable cancer risk in the workplace by OSHA? 10−3, 10−4, 10−5, or 10−6.

- Radiation. The human body is best at absorbing nonionizing radiation within which range of frequencies? 3 KHz to 30 MHz; 30 MHz to 300 MHz; 3 GHz to 6 GHz; >6 GHz.

- Thermal Stress. Calculate the estimated radiant heat load from surrounding objects with radiant temperature of 101°F using the formula R = 15(tw − 95), where: R = radiant heat load (BTU / hour), and tw = radiant temperature of surrounding objects (F).

- Toxicology. What is the major mechanism of toxicity for carbon monoxide?

- Ventilation. Calculate the air flow in cfm when the velocity pressure is 1.1 inches water and the circumference of the duct is 56.25 inches.

Sources: Example questions compiled from: American Industrial Hygiene Association, “Sample Exam Questions,” http://www.abih.org/become-certified/prepare-exam/sample-exam-questions; and courtesy of Bowen EHS CIH exam prep, https://www.bowenehs.com/exam-prep/cih-exam-prep/.

When you look at the required education, required experience, and sample questions from the certification exam, you will quickly recognize that their expertise is in the science of a Healthy Building. If something is found to be “off,” this group has the skill set to identify what that is and come up with a solution. We don’t know about you, but we would feel better sitting in our Healthy Building if we knew a CIH was determining how healthy it was.

Naturally, there are business challenges with the cost and availability of CIHs as Healthy Buildings increasingly come into the mainstream. We believe that the certification protocols and standards that will be most influential in the long run will include CIH knowledge at a scale and degree of accessibility that are both rigorous and objective, while also being widely propagated.

What Makes a Great Healthy Building Certification?

Overall, the appearance of these Healthy Building certifications is a positive sign. It proves that awareness is growing and shows that the market wants a solution. We are hopeful. First offerings always need fine-tuning, and we pointed out a few of those in this chapter. Because the demand is so high, we are confident that the market will continue to iterate until it gets this right.

Here is what “getting it right” for a Healthy Building certification protocol looks like to us:

- Evidence based and supported by peer-reviewed science

- Flexible and can incorporate evolving research and new advancements in technology

- Standardized, consistently defined, and verifiable

- Cost effective (and with a cost-benefit analysis that includes human health and performance)

- Not defined solely at one single point in time

- Administered and verified with on-site testing by experts trained in how to anticipate, evaluate, manage, and control hazards

- Entails performance verification that includes monitoring Health Performance Indicators (covered in Chapter 9), such as real-time indicators of indoor environmental quality, in areas that are representative of where people are spending their time

- Developed in close coordination with end users (for example, designers, architects, owners, investors, and tenants) and building health experts (for example, engineers, health scientists, and medical professionals)

- Recognized by the market and investors as providing commercial value

- Incentivizes shared value across stakeholders (for example, investors, owners, and tenants)

We don’t know yet what system will eventually be considered the “gold standard” for Healthy Building certifications. This section of our book will become dated very quickly. That’s a good thing: we look forward to seeing how the system evolves, and to seeing this new certification gain the same level of influence as LEED and other green building rating systems.