“Ninjas don't wish upon a star, they throw them.”

—Jarius Raphel

So what do ninjas have to do with global brand building? For me, ninja warfare provides a perfect metaphor for the scrappy kind of lean marketing that is required to enter and unlock growth in foreign markets. I am not talking about the way ninjas are typically portrayed in Hollywood, infiltrating enemy lines and assassinating emperors under the cover of night. And, I'm definitely not saying that you need to kill anyone. What I am talking about is getting inside the head of your enemies (your competition) and devising a plan of attack to beat them.

Ninjas practiced Ninjutsu, an ancient form of warfare used in feudal Japan. Ninjutsu required that warriors prepare for battle using a strict methodology that relied heavily on intelligence gathering and strategy creation.1 Ninja fighters were trained experts in reconnaissance, so they could thoroughly scout an enemy and understand its strengths and weaknesses before exploiting what they had learned to create a competitive advantage.

Jinichi Kawakami is the sixty-seven-year-old head of the five-hundred-year-old Koka ninja clan and teaches a business course at Mie University in Tsu, Japan. According to Kawakami, “Ninja[s] were skilled in many arts, but one of the most important has always been collecting information about your opposition. That is just as important in the world of business today as it was in the feudal era hundreds of years ago.”2

Ninjutsu is actually a type of guerrilla combat in which smaller groups of faster-moving fighters were able to take advantage of larger, slower-moving armies. That's because established armies, like established brands, tend to be slow and predictable. When entering international markets, global brands are often tempted to replicate their existing structure, brand associations, and value proposition, hoping what worked before will work again. Unfortunately, this kind of wishful thinking is almost always suboptimal because it is predictable, doesn't take advantage of being new, and assumes that the brand will have the same level of support in the new market as it did back home.

Like the global brand builder who is asked to enter a foreign market to compete against larger, more established local brands, ninjas had fewer resources than the established armies they faced. That's why both ninjas and global brand builders benefit from engaging in guerrilla-style, asymmetrical warfare to gain a competitive advantage.3

To win in a foreign market, you almost always have to adapt your brand's value proposition to meet the needs of local consumers and stakeholders. Like a ninja, take advantage of the predictability of established brands and learn from their mistakes and weaknesses.

Nestlé China learned from the earlier mistakes made by Kellogg to improve its launch of breakfast cereals into China.

Early on in my career at General Mills, I accepted an expat assignment in China working for a joint venture between Nestlé and General Mills. I led a successful launch of Nestlé breakfast cereals into China following a failed attempt by Kellogg in the early 1990s.

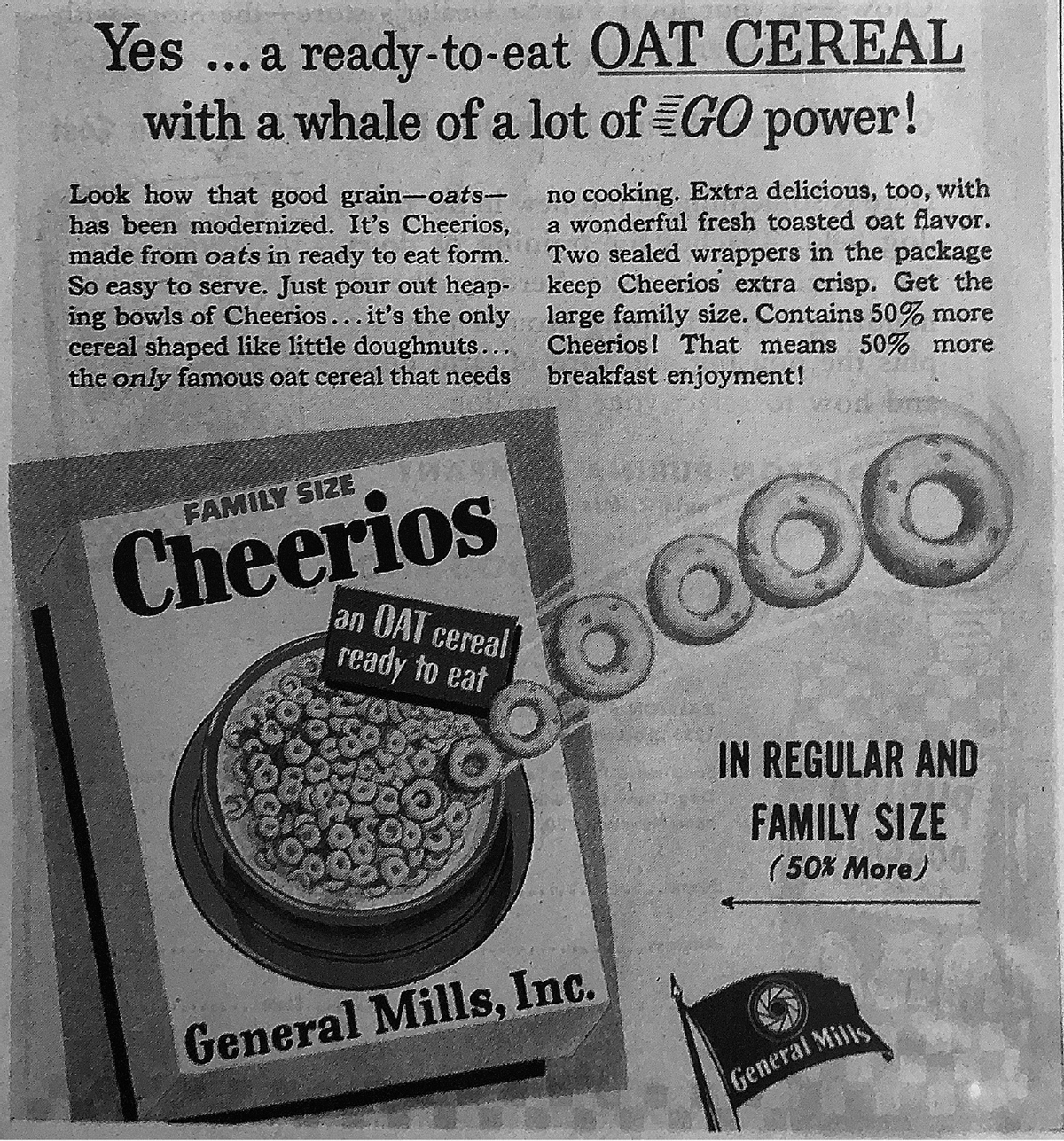

Kellogg's big mistake was trying to build the cereal category in China the same way it had in the United States in the 1940s. Back then, the popularity of eating breakfast cereal started to grow in America, as companies like Kellogg positioned cereals to adults as a convenient way to eat grains. Grains were known to be nutritious, and breakfast cereals, unlike oatmeal that required cooking, was “ready-to-eat” right out of the box (see Figure 1.1). In the 1950s, Kellogg and General Mills started leveraging the nutritional equity they had built and added more sweetness to appeal to Baby Boomer children.

Following its existing playbook, Kellogg entered China and started targeting adults with unsweetened corn flakes, rice flakes, and wheat flakes positioned as nutritious. However, Chinese adults were not looking for new nutritious breakfast solutions. They already had their traditional Chinese diet.

As my team at Nestlé prepared to enter the breakfast cereal market, we noticed how China's one-child policy had created a nation of single-child families and thought we could use this to our advantage. We discovered that the parents and grandparents of these “little emperors” were extremely motivated to find nutritious breakfast options to help their children grow up healthy. We also found that mothers in China, like their counterparts all over the world, struggled to get their children to eat a nutritious breakfast before sending them off to school. Kids in China were just as picky as kids in America and also enjoyed eating breakfast cereals because of the fun shapes, texture, and sweetness.

So when we launched breakfast cereals into China, it was with an adapted portfolio of nutritious products that we knew Chinese kids would enjoy eating. Our battle cry was “Moms trust it; kids love it.” Nestlé breakfast cereals eventually grew to become the category leader in China (see Figure 1.2).

Figure 1.1. Photo of vintage 1951 Cheerios print advertisement. Photo credit: Amy Hsu

Figure 1.2. Original launch packaging for Nestlé Milk & Egg Stars, 2003. Photo credit: Amy Hsu