“Some people don't like change, but you need to embrace change if the alternative is disaster.”

—Elon Musk

Building a differentiated brand in a foreign market requires agility. Each time you prepare to enter a new market, you must revalidate your industry assumptions and be willing to reframe your perspective of the competitive landscape. So get ready to unpack your assumptions and prepare to be surprised.

The truth is, you can't just flip a switch and change your paradigm. So here is an exercise to help you gain a fresh perspective on your competition. List out the major assumptions that underpin how you operate in your home market. Then, validate that they still apply to the new market you are trying to enter. Pay particular attention to

In today's increasingly urbanized, fast-changing environment, entering new markets with properly branded offerings has never been more necessary. On my first trip to Nanjing, China, in 1998, I visited local grocery stores and noticed that most of the products being sold were only offered in bulk-style, clear bags and hardly any had branding. At that time, Nanjing was an emerging, second-tier city in China. When I returned three years later, everything had changed. Not only were there more Western brands on the shelves, but many local brands had become more Westernized by incorporating glossy printed packaging with well-designed, illustrated logos.

In 1990, there were only ten “mega” cities in the world with more than ten million people living in them. Now, the United Nations projects that by 2030, there will be more than forty such “mega” cities globally, and by 2050, 66 percent of the world's population will be living in urban areas.1

Beyond well-known megacities like Shanghai, Mumbai, and Mexico City, there are many emerging cities that should be on your radar as you plan for growth. In the past and unfortunately even today, most large companies focused primarily on megacities, leaving emerging cities to be developed by distributors and brokers. According to Boston Consulting Group, by 2030, there will be more than one thousand cities in emerging markets with populations over half a million. That means at least an additional 1.3 billion consumers will be living in emerging market cities, compared to one hundred million new consumers calling existing developed cities their home. The implications of this change cannot be overstated. To put it into perspective, in 2005, if you wanted to reach 80 percent of China's middle class, you only needed distribution in 60 cities. In 2020, to maintain 80 percent coverage, you need distribution in more than two hundred Chinese cities.2

If that weren't challenging enough, the size of emerging market cities is evolving much faster than the behavior and perceptions of the migrants who inhabit them. This results in emerging city consumers with drastically different needs and preferences than those living in the megacities. Although it is not practical for companies to focus on every emerging city, becoming a leaner and more agile brand builder will allow you take advantage of more opportunities.

Income levels are rising across developing markets as workers migrate from rural areas into the cities. In India, for example, 40 percent of the population will be living in urban areas by 2025, and city dwellers will account for more than 60 percent of the country's total consumption.3 It is expected that this growth will also generate more disposable income and boost demand for branded products and services.

Information is power. In fact, there is a strong correlation between Internet access and purchasing power. As workers earn more money, they can afford to buy smartphones and personal computing devices. According to the Pew Research Center, many large emerging economies now have at least 60 percent of their populations using the Internet, including 72 percent in Russia, 68 percent in Malaysia, 65 percent in China, and 60 percent in Brazil.4

Thanks to this digital transformation, new urban consumers are seeing how people live in other parts of the world for the first time, and this affects their buying behavior. More access to the Internet also provides more opportunities for companies to reach emerging consumers, making it easier to sell products and services to larger groups of buyers. In 2017, online retail sales in China surpassed one trillion dollars for the first time, with rural areas growing 39 percent compared to 32 percent overall.5

Don't assume that you need to lower your price to penetrate emerging markets. Research suggests that after being exposed to a higher standard of living, many new middle-class consumers demand a taste of what they have been missing.6 According to The Nielsen Company, large numbers of consumers in developing countries are trading up on everyday items like personal care, home care, beauty, and food products. In Asia's developing markets, between 2012 and 2014, premium-tier products (products costing at least 20 percent more than the category average) more than doubled the growth rate of mainstream and value-tier products.7

We all know the expression “Fish where the fish are,” but I think this familiar saying needs some tweaking in the context of global brand building. I always tell my teams, “You shouldn't just fish where the fish are, but instead, go where you can catch fish that are big enough to get you full.”

According to Mark Johnson, cofounder of Innosight and a global expert on growth strategy, when brands enter emerging markets, they usually go for the extremes.8 First they go low, focusing all of their energy on lowering costs to make their products affordable for a large population of lower-income consumers. We have all been there, listening to colleagues say things like, “If we could just get one dollar from every person in India, we would be rich.” As it turns out, that is an extremely difficult thing to accomplish, because the average Indian consumer only spends about $1.80 USD per day.9 When brands eventually figure out that they can't make money selling at such low prices, they typically shift gears and go high, this time attacking the very top segment of the market—the small group of wealthy consumers that can actually afford their existing product line. Unfortunately, in the past, the group that most often got ignored by developed market brands was the emerging middle class.

The takeaway is: ignore the middle at your peril. Although we know the needs of the middle class are often not satisfied because they can't afford the high-end products offered by foreign brands, it doesn't mean that they don't desire something better than the low-end products they can afford.

Before launching a branded product into a new market, you need to determine the category lifecycle stage. There are five stages:

(Renovation is often overlooked but is included because it can drive new category growth and extend the demand curve.)10

It's important to remember that consumer needs change depending on the maturity of the category. You should always try to match your value proposition to the category lifecycle stage (see Figure 2.1). The same brand can usually be adapted to satisfy multiple consumer needs. For example, during the early stages of the category lifecycle (launch and growth), many “everyday” products from developed markets (e.g., coffee and ice cream) are successfully repositioned into “special occasion” or premium products when launched in developing markets.

Figure 2.1. Category lifecycle.

Humans are creatures of habit. To make a change in our behavior and instill a desire to try something new, marketers have to create a wow factor. To get people to stop what they are doing and pay attention, a new branded offering needs to surprise people. The best brands accomplish this by exceeding expectations at each link in the Branded Product Value Chain (see Figure 2.2). When brands exceed expectations, they create what is called a “value advantage.”

Figure 2.2. Branded Product Value Chain.

Figure 2.3. Value Advantage is created when perceived benefits exceed perceived costs.11

Buick captures more demand in China by appealing to a growing and more affluent middle class.

Until very recently, Buick was viewed in the United States as an old brand, driven mostly by retirees. Among younger drivers, the brand was perceived to be tired and dull. These brand associations didn't happen overnight but were built over a long period of time (see Figure 2.4), with the first Buicks manufactured in Flint, Michigan, back in 1903.12

In China, however, Buick managed to create a successful new brand image (see Figure 2.5), and there are now more than eight Buicks sold in China for every one sold in the United States. In China, the brand image is considered to be young and vibrant; Buick owners average thirty-five years of age. The brand even manages to outsell Honda, Audi, BMW, and Mercedes-Benz.13

A major reason for Buick's success in China is that first-time buyers account for 80 percent of all car purchases.14 Unlike American buyers who have a strong opinion about their father's Buick, Chinese buyers are more receptive to a new Buick narrative because they don't have strong feelings that need to be overcome. By not anchoring itself to the dated American positioning, Buick was able to appeal to an important younger demographic in China.

Figure 2.4. A 1936 vintage poster advertising Buick cars. Photo credit: National Motor Museum/Heritage Images/Getty Images

Figure 2.5. A stylish Buick presented at the Shenzhen-Hong Kong-Macao Auto Show. Photo credit: Bartekchiny/Bigstock

Starbucks resonates with today's Chinese consumers by matching its offerings to the category lifecycle stage.

Starbucks has more than 2,800 stores in China and adds roughly 500 new stores each year, making it the fastest growing Starbucks market outside of the United States.15 As in most developing markets in Asia, the coffee category in China is relatively new and still in the early stages of category development.

Before Starbucks, most Chinese consumers believed Nestlé's Nescafe instant coffee was the gold standard. Nescafe was perceived as Western and purchased primarily for gifting during the Chinese New Year.

Starbucks is considerably more expensive in China compared to the United States. In China, Starbucks is considered a premium offering. The price of a “tall” latte in the United States is roughly $2.75. That same latte in China costs about $4.60. If you factor in differences in income and purchasing power, the gap becomes even wider. The average Chinese worker makes much less than the average American, so when a Chinese consumer buys a “tall” Starbucks latte for $4.60, it actually feels like they are spending more than $7.00.16

Figure 2.6. Starbucks Roastery, Shanghai. Photo credit: Amy Hsu

Figure 2.7. Starbucks strawberry yogurt limited time offer, Seoul. Photo credit: Amy Hsu

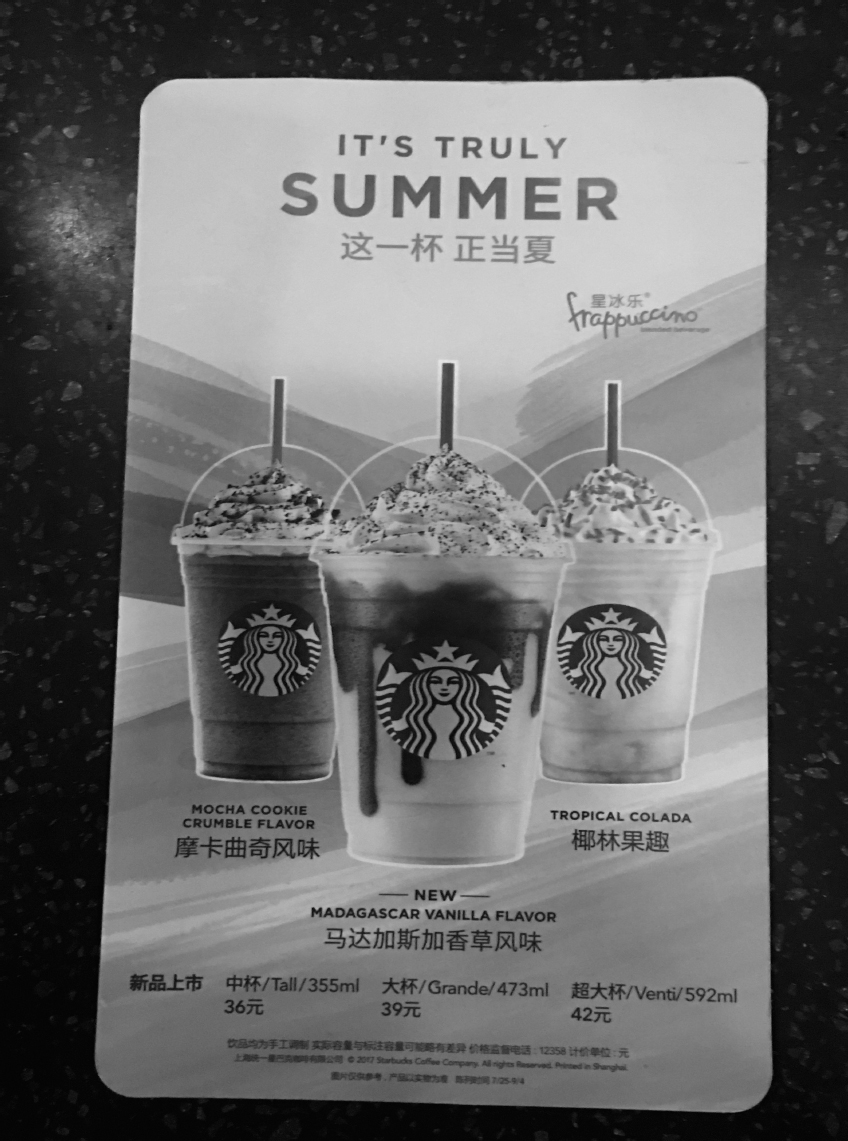

Figure 2.8. Starbucks LTO table menu coaster, China. Photo credit: Amy Hsu

You notice the difference between American and Chinese coffee culture by observing the store traffic in Starbucks. In America, the morning is the busiest time of day as customers line up for their habitual jolt of caffeine at the same time and location every day.

In China, the busiest time of day for Starbucks is the afternoon. That's when stores are filled with women sipping on dessert-style beverages and taking selfies with their drinks and friends. For these consumers, the coffee shop experience is about entertainment and experiencing an affordable luxury moment. Many of these ladies might never be able to take a trip to America, but they can, from time to time, afford to buy a cup of American coffee.

The differences don't end there, however. Just as Americans don't go to the movies to watch the same film every week, the specialty coffee drinker in Asia doesn't want to drink the same beverage every visit. As a result, in China and many parts of the developing world, the pace of innovation is fast. Large coffee chains in China typically introduce about thirty limited time offers (LTO) every year. Throughout Asia, the bestselling new drinks typically include an ingredient backstory, are Instagram/Weibo worthy (presented with visual “wow”), and incorporate multiple layers of tastes and textures (see Figures 2.6, 2.7, and 2.8 on pages 24–25).

Häagen-Dazs creates a value advantage by exceeding consumer expectations.

Häagen-Dazs operates hundreds of boutique-style ice cream shops throughout Asia that are modeled after European patisseries, with approximately 380 of them located in eighty-four Chinese cities.17

To help elevate quality perceptions, these upscale shops are intentionally placed in shopping areas populated by Western luxury brands. Häagen-Dazs sells beautifully decorated desserts and social media–worthy drinks, all served in an aspirational environment (see Figures 2.9, 2.10, and 2.11).18

In Asia's developing markets, the brand has exceeded the expectations of a growing middle-class by adapting its global platforms to appeal to local tastes. In China, flavors like Yuzu Citrus, Mango Snow Slush, and ice cream mooncakes strike the right balance between adaptation and standardization.

Figure 2.9. Exterior of a modern Häagen-Dazs ice cream store in Shanghai, China. Photo credit: Amy Hsu

Figure 2.10. A beautifully plated seasonal dessert at Häagen-Dazs in China. Photo credit: Amy Hsu

Figure 2.11. A Häagen-Dazs shop in Taipei. Photo credit: Amy Hsu

The two most common arguments for strictly adhering to a global brand positioning when entering a new market are: 1) creating financial and operational efficiencies; and 2) increasing synergies across a global organization. However, neither of these arguments matters much if the current global positioning is weak or doesn't resonate with local consumers.

In these situations, the best option is to reposition the brand to compete in the new market. Finding out that your current global positioning won't work before you launch can be a blessing in disguise. You can take the opportunity to create an improved value proposition, one that leverages the strengths of your global brand equity while minimizing local weaknesses.

One of the big differences between launching an existing brand in an established market and launching a new brand for a developing market is the awareness level of the brand. When you launch a new brand into a new market, consumer awareness of your brand will almost certainly be low. That means you have the freedom to create the perfect offering and take advantage of the incumbent's inability to quickly adapt.

DaVinci Gourmet used the brand's low awareness as an opportunity to create a new brand positioning in Asia.

In 2015, I was hired to lead the APAC brand organization for Kerry, the global owner of the DaVinci Gourmet brand. Kerry purchased this American brand in 2003 and had done very little positioning work since (see Figure 2.12). My job was to help Kerry grow the brand in Asia and make a serious run at the global beverage syrup leader, Monin.

Monin, a family-owned French company, has been making and selling beverage syrups for more than one hundred years. The brand uses a vintage-style bottle design along with a very literal ingredient story. For example, Monin names its syrups using direct French translations of the main ingredients (e.g., Pomme Verte for Green Apple) and decorates its bottles with the kind of literal illustrations you would typically find printed in a vintage provincial French cookbook (see Figure 2.13).

There were many changes underway in the coffee industry at the time I joined Kerry. The coffee category in Asia was at the beginning of what many in the industry referred to as the “third wave.” The first wave was driven by the convenience of home-brewed and instant coffee options like Folgers and Nescafe, while the second wave was fueled by chains like Starbucks elevating coffee's taste and quality perceptions for the masses. The third wave is about leveraging the entire sensory experience of drinking coffee, often using modern and scientific techniques to extract the goodness that comes from single-origin coffee beans.

Figure 2.12. Global DaVinci gourmet packaging. Photo credit: Aleksei Isachenko/ Shutterstock

Because Monin was the global leader and the brand most often used by professional bartenders and drink makers, other syrup manufacturers started to gravitate toward Monin and emulating its image. This movement resulted in fewer choices for professional drink makers searching for a more contemporary offering.

Figure 2.13. Monin global syrup packaging. Photo credit: Gary Perkin/Shutterstock

My team gained insight from dividing the competitive setup based on how traditional and literal each brand's communication was perceived by end-users. After placing all the competitors on a perceptual map, we exposed a gap in the modern/sensorial quadrant (see Figure 2.14).

Figure 2.14. Professional beverage syrup perceptual map.

Most coffee shops display their syrup bottles on the counter. My team knew that if a coffee shop wanted to communicate a contemporary sensorial image to its consumers, it would not have many syrup options available to help tell that story. At the time, awareness of the DaVinci Gourmet brand in Asia was very low, and the existing global brand positioning was perceived by end-users as being generic or “middle of the road.” So we repositioned the DaVinci Gourmet brand as the contemporary and more sensorial alternative to Monin's traditional and literal brand positioning in Asia (see Figures 2.15 and 2.16).

We knew that Monin had invested so much into establishing its traditional positioning that it would never feel comfortable drastically changing that cultivated image. We quickly redesigned every element of the DaVinci Gourmet brand and made sure that every touch point including the bottle structure, label design, and trade promotions communicated the same new contemporary and highly sensorial positioning.

Figure 2.15. Repositioned DaVinci Gourmet packaging. Photo credit: Kerry Group, used with permission

Figure 2.16. Repositioned DaVinci Gourmet packaging. Photo credit: Kerry Group, used with permission