The Other Gods of Canaan

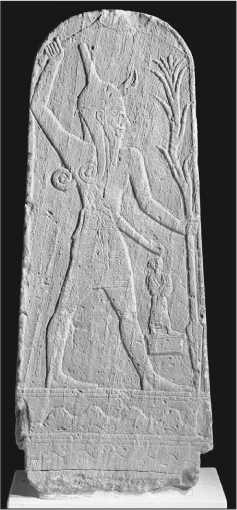

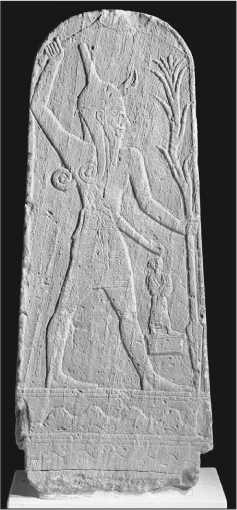

The Storm-god Baal with a Thunderbolt from Ugarit (Ras Shamra) c. 1350–1250 BCE (sandstone).

THE BELIEF IN GOD. ANCIENT UGARIT. EL AND BA‘AL. THE ONOMASTICON DOES NOT LIE. THE SOUTHERN CONNECTION.

When most people speak about God nowadays, they mean the Supreme Being, the Master of the Universe, the one “than Whom none greater can be conceived.”1 And, quite naturally, they assume that this is who God has always been. But we have already glimpsed that this is not really the God of much of the Hebrew Bible. He is not necessarily supremely powerful or omniscient or omnipresent. He is a specific, definite, being; He has a name, YHWH,58 which, like all other personal names, apparently distinguishes Him from other, potentially similar, beings. Indeed, especially in earlier books and passages of the Bible, He is explicitly a God among other gods; “Who is like You among the gods, O LORD?” is, apparently, a flattering question in the hymn of Exod. 15:11. In the same book, Moses’ father-in-law declares in evident admiration, “Now I know that the LORD is greater than all the gods” (Exod. 18:11). Similarly, Ps. 135:5 asserts, “For I know that the LORD is great, greater indeed than all the gods.” Ps. 95:3 echoes these sentiments: “For the LORD is a great God, and a great King above all gods.” Ps. 89:6 asks: “For who in the skies can be compared to the LORD, or who among the heavenly beings57 is like the LORD? A God feared in the council of the holy ones, great and awesome above all that are around Him. O LORD God of hosts, who is as mighty as You, O LORD?”

This, of course, is not a happy subject for believing Jews and Christians. It is disquieting, to say the least, to think that God has not always been understood to be what He is now—and far worse than disquieting to think that the evidence for that assertion is to be found in God’s own holy book. Still, among the many subjects that modern biblical scholars have studied, one of the most prominent has been Israel’s God Himself: At what point in their history did the people of Israel come to believe in and worship Him? What was His nature in those early days? And at what point can Israel’s religion be described as true monotheism?

Belief in—or, some would prefer to say, an awareness of—the divine is older than any religion, older than any talk about God or the gods. Some contemporary neuroscientists have concluded that this belief/awareness is hardwired into the human brain, or at least into some human brains—an ancient genetic flaw or a now-fading superior consciousness, depending on one’s viewpoint. Whatever its cause, this general turn of mind must have existed for millennia, eons, before anything resembling an actual religion or specific form of worship first appeared. As far as human history is concerned, the elusive or illusory divine was simply part of human consciousness from the very beginning.

At a certain point, however, this general dimension of human consciousness begins to take a specific form: belief in the existence of gods. This too is very ancient; no one can even guess, for example, when a belief in the gods first appeared in the ancient Near East. The very oldest texts from that region simply assume that the gods exist and always have. Indeed, long before writing was invented, Near Eastern peoples built sanctuaries and shrines to their gods, and the eerie remains of these most ancient structures offer mute testimony to the gods’ hold on people’s thought at that time. Stretching still farther back are burial and other practices that likewise seem to bespeak a belief in some sort of spiritual realm. Some scholars, working from such remains as well as from the most ancient texts we possess, have attempted to compile a developmental history of, for example, Mesopotamian religion, tracing broad lines of change; but others have found even this sort of broad history to exceed the possibilities offered by the available data.2 The most we can say for certain is that gods of various sorts seem to have been part of Semitic culture for a very long time.

The ancient conception of the gods is not particularly difficult to grasp: the gods were, to give a concise definition, the unseen causers just behind ordinary reality, the divine beings responsible for all the different things that seem to just happen in the world. Thus, the ripening of fruits on the trees and of grains in the field, the fertility (or lack thereof) of one’s flocks and herds, the coming of the rains, the movement of the sun through the sky and the regular changes of moon and stars and seasons, weal and woe, war and peace—none of these things, to a certain way of thinking, could possibly happen on their own. They must have been caused—caused by someone. After all, I know that if I throw a rock into a stream or build a new house, I am the evident cause of the subsequent plop in the water or the rickety dwelling on the hill. So similarly, even when the cause is not immediately apparent, if the crops start to ripen but are then consumed by drought, or if, instead, lightning comes shooting out of the sky to herald the life-bringing rains, these things must also have been caused. I may not see the authors of such actions, but causality itself can hardly be questioned; in this case, the cause is simply hidden—or, to put it in more Near Eastern terms, the causer is simply hidden. Enter the discrete, divine beings: it is the gods who are the hidden causers.

People did not, of course, usually encounter the gods themselves on the street; their ongoing presence on earth was to be found, as we have seen, in houses specially constructed for them (temples), where they dwelt in concentrated form inside little figurines. This compressed form of existence notwithstanding, the same gods who lived in temples also acted in the world and interacted with other gods and goddesses. These deities thus led something of a double life. The real world apparently had some sort of upper shelf or dark backdrop; the gods were present—up there, or back there—as much as in their temples, and they manipulated like puppeteers the things that make up our ordinary existence. These powerful beings were, quite naturally, on everyone’s mind. Parents gave their children names that invoked a goddess or god; people spoke of the gods’ interventions in their ordinary conversation. Bards sang the mighty deeds that the gods perform, and sages charted the movements of the stars or peered into the intestines of a slaughtered animal in order to discover what the gods had decreed for the future. Certainly, no one ever questioned the gods’ existence; one might as well question reality itself. Anything that happened in the world whose cause was not apparent was obviously their doing. Nowadays most people believe that matter is made up of molecules and atoms, even though they have had no direct experience of these invisible entities in their own lives, and even though this belief is scarcely more than a century old. How, then, could anyone doubt the gods’ existence when it was evident in all the happenings of everyday life, from the sunrise and sunset to the phases of the moon and changes in the weather, famine or feast, war or peace? And how could anyone question a way of seeing the world that had been part of people’s understanding not for a century or two, but for millennia, stretching back into the unremembered beginnings of time?

The Gods of Canaan

Israel at its start was, according to modern scholars, like other ancient peoples in this respect: there were, as far as Israelites knew, many gods and goddesses in the world, and these deities together were responsible for reality. At a certain point, however, Israelites began to assert that their God was the only deity in the world, and that the existence of other gods was in fact an illusion. How did this belief—which has had the greatest impact on human life, being espoused today by more than half the world’s population, including (apart from the relatively small number of Jews in the world) approximately 2 billion Christians and 1 billion Muslims—ever get started?

About this subject there is scarcely any agreement among today’s biblical scholars. Some few seek to claim that Israelite monotheism began very early: it was part of the “Mosaic revolution” that occurred at the very start of Israel’s existence as a people. Others assert that it was quite late—that even in the time of the Babylonian exile and the restoration that followed it, many Jews still entertained polytheistic beliefs, and that to speak of any sort of monotheism before that time is wishful thinking. If the advent of true monotheism is thus in dispute, one aspect of the question does at present seem to be building to something like a consensus. Just as a growing number of scholars have begun to see the emergence of the people of Israel as a result principally of internal developments within the native population of Canaan, so have a growing number come to see the earliest stages of Israelite religion to be virtually indistinguishable from that of their Canaanite neighbors.

In a sense, such scholars say, the evidence was always there. After all, as we have seen, God is said to have revealed his particular name (YHWH) to Moses on Mount Horeb/Sinai. The Pentateuchal sources E and P both seem to report that, until the time of Moses, the name of this deity was unknown; up until then, a passage attributed to P asserts, God was worshiped under the name “El Shaddai” (Exod. 6:2–3). Scholars doubt, however, that it was merely God’s name that changed. The sudden appearance of a new name, they say, really indicates that this deity had been unknown in Israel up to that point.3 Once Israelites started worshiping this deity, they eventually came to believe that, in fact, He had always been their God, under some other name.

If this God was a new arrival, what deity had the Israelites worshiped before? A number of references, including the verse just cited, suggest that Israel’s God had previously been known by the name ’el in some combination—’el shaddai (Exod. 6:2–3; cf. Gen. 49:25; Num. 24:16), ’el ‘elyon (Gen. 14:22; cf. Num. 24:16; Deut. 32:8–9; Ps. 73:11; 107:11, etc.), ’el ‘olam (Gen. 21:33), ’el ’elohei yisra’el (Gen. 33:20), and so forth. The word ’el, it has been pointed out, is simply a general term for “deity” and exists in many Semitic languages, including Hebrew. Indeed, we have seen that the word ’elohim, which seems to be the plural of ’el, is regularly used in the Hebrew Bible as a synonym for YHWH.4 For that reason, ancient readers of the Bible assumed that these various references to ’el, like the word ’elohim, were simply another way of referring to the one true God; they were elegant epithets for Israel’s God and were translated accordingly: “God Almighty,” “God Eternal,” and so forth.

As modern scholarship progressed, however, the suspicion grew (in part because ’el was recognized to be a common Semitic word) that ’el in the Bible might sometimes refer not to Israel’s God but to someone else’s. Perhaps the use of this name was connected somehow with Canaanite worship, which may not have been utterly eradicated by the Israelites, at least at first.5 In a famous essay published in 1929, Albrecht Alt suggested that the various ’el combinations (“El Elyon,” “El Shaddai,” and so forth) referred to little local deities or spirits (numina) associated with this or that place encountered by the Israelites.6

The Discovery of Ugarit

The same year that Alt published his essay marked the beginning of the excavation of a site on the coast of northern Syria, Ras Shamra, not far from Latakia (where the famous pipe tobacco comes from). As with so many great archaeological finds, the ruins underneath Ras Shamra were discovered quite by accident: a farmer’s plow, according to the story, bumped against a hard, unmovable object that, upon examination, turned out to be part of an ancient burial site. French archaeologists soon moved in (Syria still being, at the time, a French protectorate), and over the course of many seasons of careful excavations, they slowly revealed an undreamed-of treasure: a major city under the earth, complete with acropolis, temples, royal palaces, residential areas, and—perhaps most precious—an entire library of texts, most of which were written in a strange, unknown language. The ancient name of the site, it turned out, was Ugarit.

The script in which the strange texts were written consisted, like ancient Akkadian,59 of little hatch marks sunk into wet clay (cuneiform). But at first, no Akkadian expert could make any sense of them. It was noticed after a while that the exact same configurations of wedge marks kept recurring far more frequently than in normal cuneiform, and it dawned on two scholars—the German Hans Bauer and the Frenchman Edouard Dhorme—that those configurations might in fact represent letters rather than syllables. (Having signs for syllables means you need quite a few—separate ones for bi, ba, and bu; ti, ta, and tu, and so forth. Akkadian thus regularly uses a roster of three hundred or more signs. The new texts, on inspection, turned out to have only thirty signs. The signs thus seemed to be functioning more like the letters of an alphabet.)7 Both scholars succeeded in deciphering more than half the signs, and the results of each scholar’s decipherments complemented the other’s. Once the writing system had been cracked, there began the massive task of translating and studying the great cache of texts found at Ugarit. The language itself—which scholars termed Ugaritic—turned out to be quite close to biblical Hebrew. (Nowadays, a student who has studied biblical Hebrew can usually acquire a pretty good reading knowledge of Ugaritic in a semester.) The Ugaritic texts were of all sorts: there were letters, inventories, legal documents, commercial and diplomatic records telling of the city’s day-to-day affairs, but also tales of gods and heroes and other religious texts. The texts were found to go back to the fourteenth century BCE, a time even before that assigned to Moses and the exodus. It is from these writings that modern scholars have been able to learn much about the religious beliefs of the Canaanites in ancient times, from whose midst, as we have seen, many hold the people of Israel to have come.

At the head of the Ugaritic pantheon stood El. El was his actual name, even though the same word also means “a deity” in Hebrew and other Semitic languages.60 El was the supreme Canaanite deity and the father of other gods, sometimes referred to collectively as the “sons of El.” He is generally depicted as an old, wise, kindly, paternal figure; he created the earth and humanity itself. El had a lady friend named Athirat, mother of the gods. Although El must at one time have been the most active of the gods, at Ugarit he had begun to be supplanted by a more youthful and vigorous figure, Baal. Baal (ba‘al means “master” and was apparently at first only an epithet for the god Hadad) controlled the storm clouds and the life-giving rain; he was the “cloud rider” whose arrival was heralded by peals of thunder and flashes of lightning. He dwelt on Mount Sapan (in today’s Arabic, jabl al-Aqra‘, the highest mountain in Syria) with his consort, the bloodthirsty ‘Anat—although other Ugaritic texts identify Baal’s consort with another goddess, ‘Ashtorte/Astarte.

As details of the Ugaritic pantheon unfolded, what was striking to scholars was how much the gods of Ugarit seemed to overlap with various representations of Israel’s God in the Bible. Of course, God in the Bible is depicted in many different ways—and in any case, some overlap of general characteristics would seem almost inevitable between two central deities. Still, the very fact that, as we have seen, God is sometimes called by the name El in various combinations was certainly suspicious. If the Canaanites next door called their supreme god El, oughtn’t the Israelites to have bent over backward to avoid the appearance of worshiping the same deity? Indeed, the fact that Israel’s God was, like El, a fatherly figure (Exod. 4:22; Deut. 14:1), beneficent and kindly (Exod. 34:6 and frequently thereafter), and was frequently referred to by the same name has suggested to some scholars just the opposite, that Israel’s God was actually a development of, or had taken on the characteristics of, the old head of the Canaanite pantheon. At the same time, Israel’s God was also a bit like Baal. The same epithet used of Baal, the “cloud rider” (rkb ‘rpt), is echoed (and perhaps deliberately distorted) in the epithet of God the “desert rider” (rkb b‘rbt) in Ps. 68:4. Baal’s dwelling on Mount Sapan seems likewise to be echoed in the praise of Zion in Ps. 48, “joy of all the earth, Mount Zion, summit of Saphon, the city of the great King” (Ps. 48:2). Another hymn, Ps. 29, seemed so much like a Ugaritic paean to Baal that more than one scholar suggested that the word “Baal” had actually been erased by an ancient scribe and “YHWH” scrawled in its place.8 Some scholars even argued that an inscription found in the southland of biblical Israel spoke of God having a consort, a certain Asherah, this being the Hebrew equivalent of El’s consort Athirat.9

And yet, the Hebrew God was not principally known as El; He may be called that here and there, but, as we have seen, He is far more frequently known by the name YHWH. Where did this name come from?

The Midianite Hypothesis

It is striking that a number of biblical texts—some of them, according to scholars, going back to the very oldest layers of the Hebrew Bible—connect the home of Israel’s God with various sites to the southeast of Israel, the land once inhabited by Kenites and Midianites and Edomites. Thus, for example:

The LORD came from Sinai, and dawned from Seir [the mountain of Edom] upon them;

He shone forth from Mount Paran [precise location unknown, but generally south of Israel and west of Edom].

Deut. 33:2

LORD, when You went out from Seir, when You marched from the fields of Edom,

The earth trembled, and even the heavens poured forth, yes, the clouds poured out water.

The mountains quaked for fear of the LORD, the One from Sinai, for fear of the LORD, the God of Israel.

God came from Teman [literally, “the south,” sometimes a synonym for Edom], the Holy One from Mount Paran. Selah

His glory covered the heavens, and the earth was full of His praise.

Hab. 3:3

O God, when You went at the head of Your army, when You marched through the desert,

the earth trembled, the heavens dripped rain,

for fear of the One from Sinai, of God, the God of Israel.

Ps. 68:8–9

These very ancient texts all seem to say fairly clearly that “the LORD” was not native to the land of Israel but arrived there from somewhere else. Although the location of Sinai is today unknown, there can be little doubt that it, too, belongs to the same general area as Seir, Teman, and Paran, that is, to the southeast of biblical Israel’s territory. It is therefore certainly significant that, according to the Exodus narrative as well, Israel’s God is said specifically to dwell on “Horeb, the mountain of God” (Exod. 3:1) or on Sinai. Indeed, Moses was living with his father-in-law, Jethro, “priest of Midian,” when he happened upon this “mountain of God” and was first addressed by the deity named YHWH. Why, modern scholars ask, should the Bible report that the God of Israel was originally located far from His people, permanently settled, it would appear, on a mountain in the southeastern wasteland? The simplest answer would appear to be: because that was the truth as Israelites knew it. All these biblical texts seem to be saying the same thing, that originally Israel’s God did not live in the land of Canaan but took up residence there only after a time.

These things are hardly obscure, and it did not take modern scholars long to come up with a hypothesis to fit them: if Jethro, Moses’ father-in-law, was a “priest of Midian” and he himself dwelt not far from the “mountain of God,” then he must have been the one to introduce Moses to the worship of a deity who was in fact his God, a Midianite deity named YHWH. Moses then brought this new deity to the Israelites, claiming (à la Exod. 3:15, 6:2–3, and 15:2) that He was none other than the God worshiped by their ancestors. Jethro’s central role in this transformation of Israel’s faith was, these scholars said, deliberately obscured by the biblical narrative, but not quite successfully. After all, the book of Exodus has Jethro exclaim, “Now I know that the LORD is greater than all the gods” (Exod. 18:10), which seems to imply that, while Jethro may not have realized this deity’s great power until that moment, he certainly had known of His existence previously. (This is not true of other biblical non-Israelites: Pharaoh, for example, had never heard of this God [Exod. 5:2].) The Bible also reports that it was Jethro who advised Moses how to set up a judicial system (Exod. 18:11–24); thereafter, however, Jethro disappears and the Israelites move on alone to Mount Sinai and, ultimately, Canaan. Nevertheless, this hypothesis maintained, the religion that they brought with them was originally foreign to Canaan—it belonged to the wastelands to the south and east of fruitful Canaan, which is why it was associated with the Midianites, Kenites,10 or Amalekites,11 all nomadic or seminomadic peoples in that region.

This reconstruction, presented by F. W. Ghillany, B. Stade, and others in the nineteenth century,12 came to be known as the Midianite (or Kenite) hypothesis. It was then taken up by a number of outstanding scholars, including Hugo Gressmann, Eduard Meyer, and Hermann Gunkel,13 and more recently (and in somewhat different form) by Manfred Weippert, F. M. Cross, and others.14 As first presented, this hypothesis had no hard evidence outside the Bible to support it. More recently, some archaeological finds have been offered as partial outside confirmation. Thus, two Nubian temple inscriptions from the second half of the second millennium refer to nomads in the region of Seir as the “Shasu [![]() 3

3![]() u, that is, Bedouins] of YHWH” (though this reading is not quite uncontested).15 An inscription found at Kuntillet Ajrud, an eighth-century BCE settlement in the northern Sinai, refers to “YHWH of Teman,” or “YHWH of the south,” which could also indicate some sort of primary association with that region. (On the other hand, another inscription found at the same site refers to “YHWH of Samaria,” so perhaps both references should be taken as reflecting the location of shrines associated with this deity.)

u, that is, Bedouins] of YHWH” (though this reading is not quite uncontested).15 An inscription found at Kuntillet Ajrud, an eighth-century BCE settlement in the northern Sinai, refers to “YHWH of Teman,” or “YHWH of the south,” which could also indicate some sort of primary association with that region. (On the other hand, another inscription found at the same site refers to “YHWH of Samaria,” so perhaps both references should be taken as reflecting the location of shrines associated with this deity.)

Even if this extrabiblical evidence is something short of unequivocal, modern advocates of the Midianite/Kenite hypothesis say that the biblical evidence itself is as sound as ever—and persuasive. After all (to take up an earlier question), what purpose would have been served by biblical writers saying that the “mountain of God” had ever been Sinai—if they were free to invent history, they ought to have said that His mountain had always been Zion, in the heartland of Judah! (Even if this Zion-based God had wished to meet the Israelites during their desert wanderings and accompany them to Canaan, that hardly would have necessitated His ever having resided outside of His homeland).16 If the most ancient biblical poetry, along with the Exodus narrative, locates the first appearance of this God in the southeast wasteland—and if no pre-Israelite Canaanite text ever mentions such a divine name—then these data ought to be the starting point of any attempt to understand where this God came from and how He came to be Israel’s.

To this might be added another point. If one takes seriously the connection between the suzerainty treaty form and its various reflections in the Bible (Exodus 20; Joshua 24; the book of Deuteronomy), then one must return to a question asked earlier: why should ancient Israel have been content to think of their God as a suzerainlike figure, a conqueror come from elsewhere? Why not their own native king? The obvious answer is: because, as far as Israel knew, He did come from elsewhere. That is to say, the entire gestalt of a great suzerain who approaches a certain people and, announcing that “all the land is Mine” (Exod. 19:5), proposes that they now come under His wing makes sense only if the suzerain is known to dwell at some great distance from the people in question. At the time this image or metaphor was put forward, therefore, it would seem that Israel was in Canaan but its God was not—at least, not yet. He still dwelled far to the southeast, at the “mountain of God.”

Some scholars connect this putative southeastern location of God’s home mountain with their own scenario for the emergence of the people of Israel. If indeed those early Israelite hilltop settlements were the result of seminomads occupying the uninhabited highlands, perhaps these settlers (or at least some of them) had come in from the grazing lands of the southeast, where YHWH (according to this hypothesis) was worshiped. Trying to flesh out some of the details of this scenario, F. M. Cross has pointed to the existence of a caravan route connecting Midian with Egypt during the thirteenth and twelfth centuries; travelers on that axis might have regularly moved farther north on routes controlled by Midian and ultimately made their way to the region of Canaan.6117 If a group connected with the future Israel had followed such a path in search of lands for grazing and small-time farming, they would likely have settled first in the near-vacant steppes on the far side of the Jordan, the land that was, for a while, the home territory of the tribe of Reuben, at the southeastern corner of the future Israel’s territory. It therefore seems highly significant, Cross said, that Reuben consistently appears in the Bible as Jacob’s “firstborn.” Not Judah, which was to become the dominant tribe in the south in monarchic times, and not Joseph, progenitor of the mighty tribes of Ephraim and Manasseh, but Reuben. Presumably Reuben was said to be Jacob’s first son because the segment of biblical Israel he represented had been, at a very early point, the powerful, vanguard tribe whose land was the staging area for future Israel’s spread to the west and north. Later, even though other tribes became more powerful and Reuben’s tribe underwent a precipitous decline (reflected, inter alia, in Gen. 49:2–5), the title of firstborn was “frozen” and remained his. All this, Cross has argued, suggests that the first Israelites were seminomadic pastoralists who came from, or through, the territory of Reuben into the western and northern parts of Canaan. They brought with them the worship of a God who had been theirs down south, a deity shared by the Midianites or Kenites or Amalekites.

Indeed, some scholars have sought to connect this same itinerary with the account of the Israelite exodus from Egypt. Although few modern historians credit the tradition of a great national exodus of twelve whole tribes, most (as we have seen) nonetheless attribute some historicity to the exodus tradition. If a group of western Semites had at one point left Egypt and made their way—possibly over a period of generations—into Canaan via this same route, perhaps it was they who at some point met up with settlers of the Canaanite highlands; they brought with them the worship of their God, YHWH. Then, as they and their ideology gradually took root in the lowlands as well, this God became the deity of the inchoate group of tribes that would be Israel.18 Their God, like their exodus tradition, became “nationalized.” If so, then the etiological understanding of the story of Cain would actually be a great reversal of the historical facts (see chapter 3): it was not that the Kenites’ eponym was originally a farmer who was exiled from the Canaanite land of YHWH to become a wandering nomad, bringing the worship of his old God with him to the rugged steppes; rather, a group of Kenite-influenced nomads entered the land of Canaan in days of old and, bringing the worship of their God with them to their new home, settled down and eventually made that God the common deity of most of Canaan.

Named for God

“The biblical onomasticon does not lie.”62 The meaning of this scholarly maxim is that, while the tellers of tales may sometimes stretch the truth or even make things up out of whole cloth, they usually fail to notice the proper names in the stories they tell. Those names—to the extent that they can shed light on the ancient past—may thus provide a far more reliable, unbiased witness as to what really happened. How does this apply to Israelite religion?

As we have already seen, many personal names in the Bible, and a few biblical toponyms, contain a theophoric element—the name of a deity. The various deities evoked in ancient Israelite names can be most significant in telling us about the development of Israelite religion. It is striking that the name YHWH appears regularly in the biblical onomasticon, starting with the names of people alleged to have lived in the tenth century BCE or so, at the time of the rise of David’s mighty empire.19 It is then that one finds an abundance of such names—David’s friend Jonathan (a name meaning “YHWH has given”), David’s army chief Joab (“YHWH is [my] father”),20 and so forth. From that time on, such names come to predominate in the Israelite onomasticon. Before that time, however, the theophoric particle is much more frequently ’el: Abraham’s son Ishmael, his servant Eli‘ezer, or, for that matter, Israel. There are even some Baal names, like Gideon’s “other” name, Jerubaal (Judg. 6:32).

Completing these data is the evidence for place-names (also called toponyms). Here, the facts are even more striking: a few toponyms contain the particle ’el—Bethel, for example, or Peniel or Elaleh. There is, however, not even one toponym formed from the name YHWH.21 By contrast, there are some place-names invoking Baal or other deities, nearly forty by one recent count: Baal-perazim (2 Sam. 5:20), Baal-hermon (Judg. 3:3), Anathoth (Jer. 1:1, etc., apparently named after the goddess Anath), and so forth.22

What is one to make of these facts? The obvious conclusion would seem to be that, up to the time of David or so, people named their children by invoking El or Baal, but not YHWH. That would seem to say that the religion of YHWH really did not catch on until the tenth century or so.

Not so fast, however. To begin with, the theophoric particle ’el is altogether noncommittal: it could refer to El, but it could also be simply the generic Semitic word for a god, in this case, the God of Israel. (Plenty of biblical texts use this word to refer to YHWH.) That Israelites preferred to incorporate this theophoric particle into names up to a certain point hardly proves that they were El worshipers, or even that the name YHWH was unknown to them; in fact, ’el names continue to be used throughout the biblical period and thereafter. (It could also be, as some have suggested, that at a certain point the identities of El and YHWH were merged into one deity; see below.) The same opacity may accompany names formed with ba‘al. While Baal was indeed the name of a Canaanite god, there are some indications that ba‘al was also used at times as an epithet for YHWH (see Hos. 2:16; Isa. 1:3).23 So this name, too, appears inconclusive.

Beyond these considerations, it is necessary to factor in the conservatism that surrounds proper names in most civilizations: they have great staying power. Indeed, toponyms tend to be the most conservative element in a language. I lived for quite a few years in a place called Massachusetts. I still have no idea what the name means, but one thing is clear: this was a Native American name that somehow survived in New England despite the foreign origin and strong Christian faith of the first British settlers of the region, both of which led them regularly to confer English or biblical toponyms on the towns they founded (Boston, New Bedford, Salem, and so forth). Nor is “Massachusetts” the sole Native American survivor—in fact, the state is full of such names: Natick, Saugus, Neponset, Titicut, Nantucket, Mattapan, Nonantum, and so on and so forth. If so many native toponyms can survive the invasion of an utterly foreign people and culture, it is not difficult to understand that, in a relatively undisturbed and homogeneous population, toponyms just seem to stay on forever. Once biblical sites had been named with ’el or ba‘al names, they tended to stay that way no matter how people’s loyalties or beliefs subsequently changed.

Personal names are not far behind toponyms in their conservatism. Many Americans named John or Mary, William or Elizabeth or Frederick, have no idea what their names actually mean or where they originally came from; for all they know, they could be Greek or Hebrew for “frog’s head” or “eternal wallflower.” It does not matter; these people were named after their lamented uncle Fred or great-grandmother Mary, or simply because the name pleased one or both of their parents—and this is altogether typical of how people’s names are chosen in many different societies. (Even when modern-day parents look up names in one of those What Shall We Name the Baby? books, they are choosing from among established names rather than creating a new one; what’s more, they are rarely even interested in the etymology given for the name they choose—a good thing, since many of the etymologies supplied in such books are wrong.) Thus, personal names tend to be almost as conservative as toponyms.

For this reason, one ought not to be too quick to assign dates for the spread of the worship of Israel’s God on the basis of the onomasticon. Nevertheless, the relative frequency of ’el in personal names at the early end of Israel’s history, and the relative frequency of YHWH among figures from the tenth century and later, does seem to dovetail with the other factors already seen. At an early point, scholars suppose, the future territory of Israel was simply part of the great Canaanite cultural continuum; the inhabitants worshiped El and Baal and the other gods and goddesses known from Ugarit and elsewhere. At some later point, “Israel” began to emerge on the Canaanite hilltops. If (as some scholars believe) those first Israelites included pastoralists who had originated in or had passed through the rugged steppes around Sinai/Seir/Edom/ Paran/Teman, they may have brought with them the worship of the God who resided there, YHWH, “the one of Sinai.” This worship they passed on to others—other mountaintop settlers, and eventually Canaanites elsewhere in the land. Not long after that, they proclaimed this God their king, who, like a conquering suzerain residing at some distance from them, could nevertheless call up their troops to muster and could issue laws to be obeyed.

This notwithstanding, devotees of this new deity were hardly likely to have thrown off their old gods and old religious practices. Why should they have? Even if the somewhat ambiguous wording of the Ten Commandments (“You shall have no other gods before Me [or beside Me]”) is interpreted to mean that no other gods were henceforth to be worshiped at all, and even if this commandment is associated with the time of Israel’s first emergence in the Canaanite highlands (and both these contentions are doubted by some scholars), that would hardly guarantee that the new Israelites would have made a clean break with their religious past. History is full of examples of the exact opposite. New gods arrive and are worshiped alongside old gods, or are sometimes identified with old gods (so that Zeus equals Jupiter, Mars equals Ares, and so forth), or old forms of worship are adapted to the newly arrived faith. Along the lines of the latter: many religious Christians today buy a Christmas tree for their houses, put up mistletoe in their doorways, and sit around the yule log on Christmas Eve—and they fully believe that, in so doing, they are observing this Christian holiday. But of course all of these customs are actually pre-Christian, “pagan” practices that were taken over by Christianity. For that matter, some American Jews have recently taken to purchasing an annual “Hanukkah bush”—an obvious attempt to create a parallel to the Christmas tree in their own religion. All these are examples of what scholars of religion call religious syncretism.24

Something similar, scholars say, may well have happened in ancient Canaan. Whenever it was that the worship of YHWH reached them, many Canaanites must have understood this new deity to be something like the equivalent of El and Baal. That is why they referred to Him by some of the same epithets and depicted Him like El, as a kindly father figure, or like Baal, as a powerful and sometimes violent deity, accompanied by the accouterments of storm clouds, lightning, and thunder; and that is why they sometimes set up a Canaanite-style sacred pillar (ma![]()

![]() ebah) to Him or planted a sacred grove (asherah) as part of their worship.25 Indeed, in the minds of ordinary people, the distinction between this deity YHWH on the one hand and El and Baal on the other may have been quite blurry. (Some scholars have gone so far as to suggest that the name YHWH itself was originally an epithet for El and only gradually developed into the name of a separate deity). Worshipers of the new deity may have sometimes converted sites that had been sacred to these other gods into sites dedicated to Him,26 as well as building new temples that followed the same plan as temples built elsewhere to the gods of Canaan. But it also seems possible that this God was worshiped alongside other gods and goddesses for quite some time; the Ten Commandments notwithstanding, the historical reality—as evidenced in the Bible itself as well as by archaeological finds—was apparently rather different.27

ebah) to Him or planted a sacred grove (asherah) as part of their worship.25 Indeed, in the minds of ordinary people, the distinction between this deity YHWH on the one hand and El and Baal on the other may have been quite blurry. (Some scholars have gone so far as to suggest that the name YHWH itself was originally an epithet for El and only gradually developed into the name of a separate deity). Worshipers of the new deity may have sometimes converted sites that had been sacred to these other gods into sites dedicated to Him,26 as well as building new temples that followed the same plan as temples built elsewhere to the gods of Canaan. But it also seems possible that this God was worshiped alongside other gods and goddesses for quite some time; the Ten Commandments notwithstanding, the historical reality—as evidenced in the Bible itself as well as by archaeological finds—was apparently rather different.27

How much polytheism existed in Israel, and for how long, is still hotly debated among scholars. Since biblical texts themselves may have been out to prove a point at the time they were written or may reflect the religious prejudices of much later authors or editors, scholars tend to give greater weight to evidence from outside the Bible—inscriptions and other archaeological finds. But such evidence itself is open to different interpretations. For example, does a profusion of little palm-sized statuettes of naked goddesses found at various Israelite sites say something profound about the state of the owners’ religious beliefs, or did such objects have approximately the same significance as a rabbit’s foot key chain in our own day?28 Some scholars have claimed—on the basis of biblical and extrabiblical evidence—that Baal was not only worshiped alongside YHWH by some northern Israelites (1 Kings 18:20), but that these two deities were considered coequal partners whose combined worship was something like the official religion of the northern kingdom.29 On the other hand, in a ninth-century Moabite inscription (the Mesha stele, on which see below, chapter 29), the Moabite king boasts of pillaging objects sacred to YHWH; no other god or goddess is mentioned. This is certainly significant.30

One scenario for the development of Israel’s religion posits the coexistence of different groups or parties among the people, most of whom were syncretists of one sort or another.31 Starting as early as the eighth or ninth century BCE, however, a more exclusivist form of Israel’s religion would have begun to emerge. This take-no-prisoners faith, which may have been inspired by early prophetic circles, had little tolerance for Baal worship or other cults; it sought to root out anything that smacked of pagan ceremonies in order to draw the clearest distinction between the worship of YHWH and that of other gods. At first, not everyone subscribed to this “extremist” position; the worship of other gods and goddesses may well have continued in other circles. Ultimately, however, the exclusive devotion to Israel’s God came to be enshrined in the laws of Deuteronomy and led to Josiah’s great religious reform in the seventh century. That may not have meant the instant disappearance of polytheism, but it certainly changed the religious landscape. The distance is not far from such an exclusivist faith to the affirmation that other gods are not only unworthy of worship, but utterly powerless or even nonexistent, an illusion: “The LORD is God in the heavens above and on the earth below; there is no other” (Deut. 4:39). This is true monotheism. Yet even in later times, according to scholars, there is evidence that some Jews continued to worship other deities alongside of Israel’s God.32 When one considers the matter in the abstract, it should hardly seem surprising that people were reluctant to abandon the basic notion that many different gods and goddesses are responsible for the multifaceted reality of our lives. But the monotheistic idea did eventually triumph. The author of the book of Judith (third or second century BCE) was probably describing quite accurately his or her own era by having that book’s heroine proclaim,

“For never in our generation nor in these present days has there been any tribe or family of people or city of ours which worshiped gods made by [human] hands, as was done in days gone by; for that was why our fathers were handed over to the sword, and to be plundered, so that they suffered a great catastrophe before our enemies. But we know no other God but Him.”

Although the path to true monotheism was long, it was eventually adopted by all Jews. Moreover, the triumph of this way of thinking in biblical times was reenacted subsequently throughout much of the world: in Europe, Africa, Asia, Australia, and the Americas, the monotheistic understanding of reality has been taken over by the most diverse populations. Today, it may truly be said to characterize the thinking of much of humanity overall.

A Simple Faith

Before we leave those early mountaintop settlements, one further aspect of life there needs to be stressed: its simplicity. To be sure, since the Industrial Revolution, rustic simplicity has been the subject of much nostalgia and not a little romanticizing; modern-day historians are still sometimes wont to find simplicity where it wasn’t really, as well as to equate the simple with the good. That notwithstanding, archaeologists are certainly correct in highlighting the apparent ethos of simplicity embodied in various aspects of those early highland villages.33 The people who lived there dwelt in small, unadorned houses of three or four rooms, which were apparently occupied by a father, mother(s), and their children (and perhaps, if there was room, other immediate relatives as well). There was nothing elegant about these houses—in fact, the family members shared their living quarters with some of the family’s livestock, who lived on the bottom floor during at least part of the year and whose pungent odor filled the air. (Keeping a donkey or a cow or two inside the house itself not only gave these valuable animals safe shelter but also provided additional warmth for the family during the chilly months of winter.)

Such individual houses were grouped together, and sometimes walled off, in ways that make sense only if one assumes that these areas constituted larger family compounds, presided over by the aging paterfamilias, who lived in one of the houses.34 Indeed, it seems altogether possible that nearly all the inhabitants of a hilltop village were linked by kinship ties of one degree or another.35 Thus the villagers—brothers and uncles, cousins and in-laws—lived together and eked out a meager living by farming the terraces that had been laid out along the sloping hillsides (these are the “elevated fields” of Judg. 5:18 and 2 Sam. 1:21),36 as well as by keeping sheep and goats and other animals. (Eventually, of course, there would not be enough farmland or grazing land available for the increasing population, so younger sons or other relatives had to be split off from these ancestral villages.)37 The rainy season, from mid-October through March, provided the moisture needed to grow crops as well as for drinking water, stored in cisterns lined with waterproof lime plaster.38 The dry period lasted from April or May through September; it was certainly cooler in the highland villages than in the valleys, but still quite hot (and dry) in summer. The changing seasons, whose regular rhythm is preserved in a Hebrew inscription of the late tenth century (the Gezer Calendar),39 left their imprint on the villagers’ way of life and way of thought; the crops they grew and ate, like the animals they raised and bred, kept them altogether tied to the cycles of nature.

The religious practices of these people were quite in keeping with the other aspects of their life, archaeologists say; here too, simplicity reigned. It is not possible to know for sure which deity or deities the villagers worshiped (or when they worshiped them); it may well be that a variety of gods and goddesses were at first honored in the highlands. The archaeological remains suggest, in any case, a rather uncomplicated religious regime, practiced in individual homes or villagewide, in “cult rooms” and local shrines (“high places”), or in open-air, hilltop areas like the twelfth-century “Bull Site” discovered in northern Samaria,40 as well as at a few actual temples of widely differing design.

Among others, the God YHWH was worshiped in those hills. Particularly fascinating about this particular deity must have been the apparent absence of cultic images representing Him. The biblical prohibition of worshiping such images, scholars have suggested, may be relatively late,41 but judging by the evidence, such a prohibition was apparently in effect from earliest times.42 It is difficult to say for sure what this evidence means, but it certainly suggests that, for the adherents of this God, He must have somehow seemed—despite other similarities and even syncretisms—different from other deities. He did not (as we have seen to be the case with the gods and goddesses of Mesopotamia) dwell inside a statue set off in a magnificent house (that is, a temple) constructed for Him. Instead, He was worshiped at what appear to be deliberately crude installations: perhaps He might infuse or appear above a standing stone (ma![]()

![]() ebah) or in a sacred grove (asherah) for a time, or else reveal Himself to a chosen servant at an oak tree or other outdoor site; then He disappeared. His presence, in any case, was not captured by the skilled work of human hands. This practice may be said to reflect a similar aesthetic of religious simplicity, perhaps a historic descendant of the outlook of those early hilltop settlers. Under this same rubric of simplicity one might list the blunt laws of the Ten Commandments—“Do this!” and “Don’t do that” (so different from the complicated case law of Mesopotamian legal codes)43—which, it has been suggested, may owe their origin to this same period of early highland villages. In keeping with this same aesthetic of religious simplicity is the Bible’s commandment to build only plain, dirt altars or, if stones were to be used, then only unhewn stones (Exod. 20:24–25). It is certainly tempting for some scholars to see in all this a single cultural continuum. Where else in the Bible does this same mentality show itself?

ebah) or in a sacred grove (asherah) for a time, or else reveal Himself to a chosen servant at an oak tree or other outdoor site; then He disappeared. His presence, in any case, was not captured by the skilled work of human hands. This practice may be said to reflect a similar aesthetic of religious simplicity, perhaps a historic descendant of the outlook of those early hilltop settlers. Under this same rubric of simplicity one might list the blunt laws of the Ten Commandments—“Do this!” and “Don’t do that” (so different from the complicated case law of Mesopotamian legal codes)43—which, it has been suggested, may owe their origin to this same period of early highland villages. In keeping with this same aesthetic of religious simplicity is the Bible’s commandment to build only plain, dirt altars or, if stones were to be used, then only unhewn stones (Exod. 20:24–25). It is certainly tempting for some scholars to see in all this a single cultural continuum. Where else in the Bible does this same mentality show itself?

It is, scholars say, dangerous to look to the narratives of Genesis for a reliable source of information about ancient times: the time of the composition of these narratives is widely disputed, and as we have seen, many scholars in any case believe them to be etiological tales quite unrelated to the persons or times they describe. Still, one cannot but be struck by the great gap separating the life of the patriarchs, including their religious practices, from those of later Israelites. Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob wander about Canaan, building here and there a rude altar to their God. No professional clergy exists in their world, nor any complicated rules of purity and impurity such as already held sway in Mesopotamian temples and would eventually take root in the rules governing Israel’s priests. Instead, the patriarchs themselves slaughter and sacrifice animals to God at their homemade altars, spontaneously turning to God in prayer and acknowledgment, wherever they might happen to be. God sometimes appears to them in the guise of a fellow human being, at least for a time—then they recognize the truth and fall to the ground in worship. It is difficult to imagine how a later Israelite, raised on the notion of temples staffed by cadres of cultic specialists—priests schooled in the rules of proper slaughter and the avoidance of any cultic impurity, who alone were authorized to come close to the place where the God of Israel Himself dwelt, enthroned in man-made splendor—could have thought that some other reality was even possible. For that reason, among others, some scholars cling to the idea that behind these stories stand traditions that are indeed quite old.44 The traditions do not go back, these scholars theorize, to patriarchal times, as Albright and others once thought; instead, the picture of life reflected in them seems to belong to the period of those hilltop settlements, when a paterfamilias presided over his extended family of farmers and shepherds, perhaps splitting off a branch of the family “because the land could not support both of them living together, since their possessions were so great that they could not live together” (Gen. 13:6), building altars and “calling on the name of the LORD.” That God was none other than the “One of Sinai” who was, increasingly, the focus of the highlanders’ piety.