The Psalms of David

THE BOOK OF PSALMS

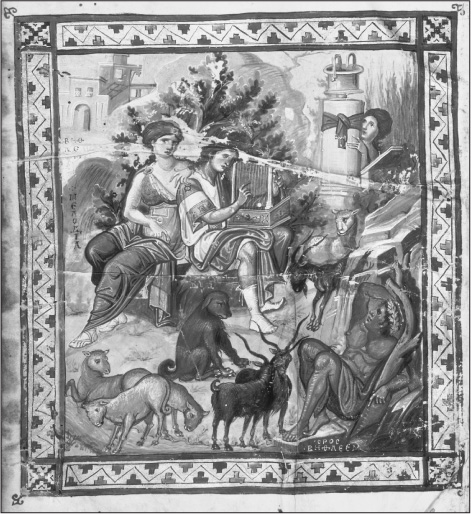

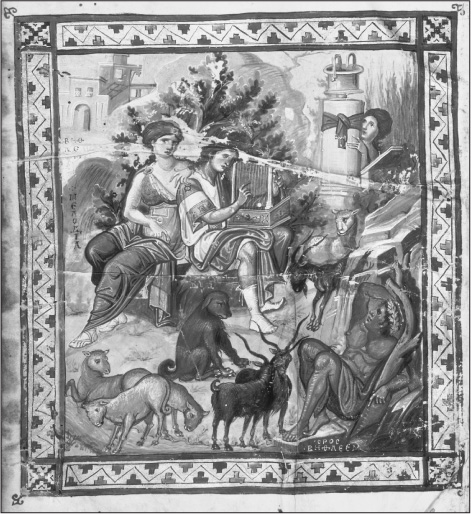

David Playing the Lyre, from the Paris Psalter.

“TO DAVID.” PSALMS AND CULTIC WORSHIP. GUNKEL’S CATEGORIES. UGARIT AND THE PSALMS. DESPIRITUALIZATION.

Why were the Psalms written—and who wrote them? Here is another subject on which ancient and modern commentators disagree.

The book of Psalms is the Bible’s book of the soul. In psalm after psalm, the human being turns directly to God, expressing his or her deepest thoughts and fears, asking for help or forgiveness, offering thanks for help already given. And so, for centuries and centuries, people have opened the book of Psalms in order to let its words speak on their behalf: “O God, You know my foolishness; the things I have done wrong are not hidden from You” (69:5). “O God, you are my God; I long for You, my soul thirsts for You” (63:1). “I thank the LORD with my whole heart; let me tell of all the wonderful things that You have done” (Ps. 9:1). “Why, O LORD, do You stand far off? Why should You hide Yourself in time of trouble?” (10:1). These psalms—in fact, all the Psalms—open a direct line of communication between us and God. No wonder, then, that the pages of the book of Psalms tend to be the most worn and ragged in any worshiping family’s Bible. And even Americans who know nothing else of Scripture often know Psalm 23 in the majestic language of the King James Version:1

The LORD is my shepherd; I shall not want.

He maketh me to lie down in green pastures: he leadeth me beside the still waters.

He restoreth my soul: he leadeth me in the paths of righteousness for his name’s sake.

Yea, though I walk through the valley of the shadow of death, I will fear no evil:

for thou art with me; thy rod and thy staff they comfort me.

Thou preparest a table before me in the presence of mine enemies: thou anointest my head with oil; my cup runneth over.

Surely goodness and mercy shall follow me all the days of my life: and I will dwell in the house of the LORD for ever.

Where did the book of Psalms come from? Tradition assigns its authorship to King David. The reason is obvious enough: roughly half of the Psalms (73 out of a total of 150) have the phrase “to [or of] David” (ledawid) in their title or heading, for example, “A Psalm of David” (Psalm 15), “A Prayer of David” (Psalm 17), “To the leader. Of David” (Psalm 11), and so forth. Some of these headings actually spell out the circumstances that led David to compose the psalm in question: “A psalm of David, when he fled from his son Absalom” (Ps. 3:1); “Of David, when he feigned madness before Abimelech, so that he drove him out and he went away” (Ps. 34:1), and the like. Although quite a few psalms do not have a heading (and a few have headings that mention other biblical figures), it soon became traditional to think of David as having written all of them.2

Modern biblical scholars inherited the tradition of David’s authorship, and at first they raised no questions about it. True, some psalms seemed, on the face of things, to speak of a time long after David’s death. For example, the well-known opening verses of Psalm 137 read:

By the rivers of Babylon—there we sat down and wept as we remembered Zion.

On the willows in its midst we hung up our harps.

For there our captors demanded we sing songs, and our tormentors called for entertainment, “Sing us one of those songs of Zion!”

How could we sing a song of the LORD’s in a foreign land?

The setting is obviously Babylon—apparently at the time of the Babylonian exile (for when else did the Jews have Babylonian “captors” and “tormentors”?). That was fully four centuries after David’s death. As we have seen, however, David was widely understood to have been not only a singer, but a prophet. Perhaps, people reasoned, David had foreseen in the tenth century BCE what God had in store for Israel in the sixth; he wrote this song so that his people might have it in their darkest hour. The fact that the psalm also mentioned the Edomites only strengthened this hypothesis:

Repay, O LORD, the Edomites, for the day Jerusalem fell—

how they kept saying, “Strip her down! Strip her down to the foundations!”

By the time of the ancient interpreters, Edom was becoming a symbolic name; it did not only designate the actual kingdom to the south of Judea, but was understood to be an oblique way of referring to Rome.3 If so, interpreters said, Psalm 137 was not only David’s prophecy of Jerusalem’s destruction by the Babylonians; it also contained a hint that the Holy City would be destroyed a second time, by the Romans of the first century CE.4

By the middle of the nineteenth century, however, scholars began to have their doubts. To begin with, they realized that the expression ledawid could mean many things: “for David,” “about David,” or “belonging to David” are equally acceptable understandings. Perhaps someone else wrote these psalms about David or on David’s behalf. Moreover, the Bible sometimes uses personal names to refer to an office—“Aaron” to mean any high priest, for example. So ledawid could actually refer to any Davidic king:68 this psalm might have been written for the Davidic king Josiah, that one for some other Davidic descendant.5 Perhaps ledawid was a simple fraud, added in by editors to help legitimate the role that psalmody came to play in later times.6 To these was added yet another possibility: since ledawid was found specifically in the psalm’s heading, it seemed reasonable that this might originally have been some sort of scribal note indicating where the psalm had come from, that is, it belonged ledawid, to the Davidic (or royal) collection of psalms, as opposed to some other source or collection.7

Considering all these possibilities, there no longer seemed to be any good reason to understand the phrase ledawid as an indication of authorship.8 For a time, scholars still accepted the idea that David might have written those psalms that specifically mentioned circumstances in his life (like “A psalm of David, when he fled from his son Absalom” in the heading of Ps. 3:1). Eventually, however, the authenticity of these headings came to be doubted as well. Scholars nowadays believe that such headings are actually the work of much later scribes who—perhaps no longer understanding the original meaning of the phrase ledawid—sought to flesh out the circumstances under which David might have written the psalm in question. Being quite familiar with David’s biography as narrated in 1 and 2 Samuel, these scribes simply chose some incident in David’s life as having been the occasion for his writing this particular psalm and stuck a reference to it in the heading (often quoting directly a phrase from 1 or 2 Samuel).9

In addition to the new understanding of ledawid, there were other indications that seemed to rule out Davidic authorship. Apart from Psalm 137 and its reference to the Babylonian exiles, a number of psalms contained what looked like obvious clues that David could not be their author. Many, for example, refer to worshiping God in Jerusalem or Zion or on God’s “holy mountain” as if this were a long-established practice. But the Jerusalem temple was, according to the account in 1 Kings, built only in the time of David’s son Solomon. And beyond this specific anachronism, there was the whole matter of the psalms’ language.

Every language changes over time—in fact, in a remarkably short time. This lesson was brought home to me once when I was reading The Wonderful Wizard of Oz to one of my children. It starts off with Dorothy’s house being swept up by a cyclone and carried off to parts unknown. “What’s a cyclone?” my son asked, and I answered immediately, “a tornado.” That word he knew. The book had been written only seventy-five years earlier, but in that time the previously disdained “tornado” had come back to replace “cyclone” in normal American usage.10 Words also vary from place to place. Depending on where you were born in America, you refer to what I call “pancakes” as “griddle cakes,” “hotcakes,” “flapjacks,” or yet something else. Traveling around the country, I have noticed that local TV reporters in some regions refer to what New Englanders call an “accident” on Route 91 as a “crash.” Of course, both words exist for all speakers; it is just a matter of local preferences.

The same thing happened with biblical Hebrew—it varied from place to place and also changed over time. When scholars looked closely at the Psalter, they began to realize that its language was not all of one piece. Some psalms, like Psalm 1 or 119 or 145, used terms or expressions that were simply not found in the earlier parts of the Bible but that existed in abundance in its latest datable books. It seemed unlikely that David, even if he were a prophet, would have used a word that his own contemporaries had never heard of. Other words actually changed their meanings. To David, the word shalal meant “spoils of war, booty” (2 Sam. 3:22); this meaning persisted into later times, but then a new meaning developed, “wealth” or “treasure” (as in, for example, Prov. 31:11, “Her husband’s heart relies on her, and wealth will not be lacking [in the household]”). Why would David have used the word in the latter sense (“I rejoice in Your words as someone who has found great shalal,” Ps. 119:162) when his contemporaries would have misunderstood him to be comparing God’s words not to precious treasure but to plundered goods?11

What’s more, David was a southerner, born and bred in Judah. But a number of psalms are written in a distinctly northern Hebrew—for example, they say mah to mean “don’t,” an altogether northern way of speaking (Song 5:8; 7:1; 8:4 [cf. 2:7]). When scholars find this mah, along with other northernisms and even evocations of northern geographic sites,12 clustered together in Psalm 42, it seems to them that the author of this psalm must have come not from Judah but some northern location. In short, the great chronological and geographical span indicated by the Psalms’ language ruled out a single author or even a single period: the Psalms were written in different places and over a long span of time.

But if David did not write the Psalms, who did? For a time, biblical scholars looked to later figures—Ezra, for example—as the potential authors of some of the Psalms. But then, along came the great German critic Hermann Gunkel, and scholars’ ideas about the Psalms changed radically.

Throughout his research, Gunkel had sought to understand why biblical texts had been composed; to his mind, writing literature or seeking some form of self-expression was a later pursuit, and it would be anachronistic to attribute such a purpose to biblical authors. Instead, what they composed must have had some practical purpose—they must have intended their works to fit into the life of the community somehow and to be used in a certain way or on certain occasions. He therefore sought to uncover what he called a text’s Sitz im Leben, its setting in daily life.

What was the Sitz im Leben of the psalms? Since many of them referred to “coming before” God’s presence, entering “Your house,” bowing down in “Your holy place,” walking around “Your altar,” making “free will offerings,” offering “sacrifices in His tent,” and similar things, it seemed to Gunkel that a great many psalms must have been composed to be recited in a temple or sanctuary of some sort. Certainly communal offerings, as well as festivals and other special occasions, might likely call for special choirs to sing hymns at a temple.13 That seemed to be the case elsewhere in the ancient Near East: by the time Gunkel had begun his investigations, scholars were aware of numerous Egyptian and Mesopotamian hymns and prayers whose connection with temples and sanctuaries was quite explicit. So perhaps that was where at least some of the Psalter’s songs had originated.

Quite apart from festivals and communal occasions, individual worshipers coming to the temple might have chanted (or had chanted for them) the words of one or more of the psalms. It is true, of course, that in ancient worship, the sacrifice itself was the “main event”; words apparently played a lesser role. Still, we know of a few specific instances in which, when individuals brought an offering to a temple, that act was accompanied by certain words. For example, when ordinary farmers arrived in Jerusalem with their obligatory annual “firstfruits” offerings, they would have to accompany this gesture with some words. In this instance, the words were completely standardized: every Israelite bringing his firstfruits had to declaim exactly the same formula (Deut. 26:5–10). But what about other offerings—a voluntary sacrifice, for example, or the payment of a vow? It would seem only reasonable that worshipers who brought these offerings would have said something as well; the same logic presumably applied to people who came to the temple to ask for God’s help. Yet the Bible is quite silent about all these cases; apparently, no standard formula existed for them. What does exist is a biblical book containing 150 psalms, some of which ask for help while others offer thanks. It has thus seemed plausible to many scholars that worshipers in such circumstances may have had recourse to one or more of these psalms. Indeed, temple officials may have routinely sought to match such people up with the particular psalm that most suited their specific circumstances. And so, “What’s this for?” the priest might have inquired. “Recovery from illness,” the visitor would reply. “Okay,” the priest would say, and, after he had signaled the choir or perhaps a lone singer, the opening strains of Psalm 30 would soon fill the air:

I will exalt You, O LORD, since you have drawn me up, and have not let my foes rejoice over me.

O LORD my God, I cried out to You for help and You healed me.

O LORD, You brought up my soul from Sheol, restored me to life from among those gone down to the Pit.

Such a hypothesis, scholars noticed, seemed to fit well with a rather striking feature of the Psalms, their lack of specificity.14 For example, a great many psalms (including the one just cited) speak of “my enemies” or “my foes,” but they rarely say anything more specific. Personally, if I had my own thirty seconds to stand directly before God and discuss my enemies, I would not beat around the bush: “Punish N———,” I would say to Him, mentioning by name a certain prolific but misguided student of rabbinic Judaism; or “Squash W———,” I would urge, referring to someone who has had the temerity to disagree with some of my ideas about biblical poetry. But the Psalms never mention names. On the contrary, they are full of metaphors that could apply to almost anyone—“roaring lions” threaten the Psalmist or “bulls of Bashan” surround him; he overcomes snakes and panthers, jumps over traps that have been dug for him, and escapes snares that have been spread out for him. And it is not just a matter of enemies. The psalmist begs to be saved from the underworld, Sheol, the gates of death, and so forth—but he almost never gets around to saying what’s wrong with him or even what makes him think such danger is imminent. It seems to scholars, therefore, that the great variety of psalms in the Psalter on the one hand, and their somewhat vague language on the other, derive from the balancing of two contrary tendencies. A psalm had to be somewhat individualized, reflecting the specific occasion that had brought a person to the temple; so there had to be a lot of them. On the other hand, such psalms could not be overly specific, since they had to be used again and again for a multitude of different worshipers, each of whose circumstances would be somewhat different.

To Gunkel, and even more to those who followed in his footsteps, the temple thus seemed to be the main institution for which psalms were written. It now appeared almost impossible that David had ever had anything to do with their composition—nor was there any reason to assume that the Psalms had been written by Solomon or Ezra or any other known individual. Instead it now seemed most likely that the authors of most of the Psalms were people directly connected with the temple setting—priests or Levites who worked there.

Types of Psalms

One striking feature of the book of Psalms is the great variety of material in it: some psalms are happy, some are sad; some seem to be tied to a particular occasion or time of year, others are altogether general and might be recited by anyone at any time. To better understand what each particular psalm was saying and why it had been written, Gunkel embarked on that great Germanic occupation: classifying.15 He set out to organize the different psalms into different groups according to their apparent purpose and/or occasion, as well as to determine on whose behalf they seemed to speak. In this effort of classification, Gunkel was followed by his (Scandinavian) student Sigmund Mowinckel and still more recent scholars.

Though much has been made of the different psalm types that have been identified, the results have, if truth be told, rarely gone beyond the obvious. Some psalms are written in the first person singular and seem therefore to have been intended to be recited by individuals (though this turns out to be true of only some first-person psalms);16 others are to be spoken by, or on behalf of, the collectivity. A great many psalms are requests for something (Gunkel and other German scholars called them Klagen, “laments”—but they are really petitions for help by the psalmist, who, in the course of asking, usually also bewails the dire circumstances in which he finds himself). Others are hymns or songs that praise God; these are distinct from psalms of thanksgiving, which express gratitude for some particular act of divine beneficence. Apart from these are certain narrower, more specific types: psalms that celebrate God’s kingship, psalms of Zion, pilgrim psalms, festival psalms, psalms of the king, wisdom psalms, and so forth.

Having identified these various types, Gunkel and other scholars also sought to find in them a standard form. The idea is that, just as a business letter has certain essential elements (date at the top; then name and address of intended recipient; “Dear Sir,” and so forth), so each of the different types of psalms must have developed its own standardized content. Thus, psalms of praise often have a standard opening, in which the psalmist exhorts himself or some group of people to pay tribute to God: “I will give thanks to the LORD with my whole heart” (Psalm 9); “Bless the LORD, O my soul” (Psalm 103); “Sing aloud to God our strength” (Psalm 81); “Sing to the LORD another song” (Psalm 96). Prayers (petitions), on the other hand, never have this kind of opening. Instead, they tend to begin with a blunt cry for help, followed immediately with a “for” clause to support their plea: “Protect me, O God, for in You I take refuge” (Psalm 16); “Vindicate me, O LORD, for I have walked in my integrity” (Psalm 26); “Be gracious to me, O God, for people trample on me” (Psalm 56).

Beyond their opening words, psalms also demonstrate certain standard, conventional elements.17 For example, prayers that ask for help often describe the psalmist as “poor,” “downtrodden,” or “indigent.” For a time, scholars thought that these psalms were meant to be recited by Israel’s underclass, people too poor to bring sacrifices. Now it seems that, on the contrary, any suppliant, even a king, would describe himself as poor before God—this was just standard petitionary language. Elsewhere in the Bible, when people suffer or get sick, the details are usually sketchy. When King Hezekiah is sick to the point of death, the narrative says nothing more than that: we never learn the nature of his illness or his symptoms. But in the book of Psalms, the text sometimes goes on and on about personal suffering, since presumably on hearing such things, a merciful God will be forced to act:18

I am poured out like water, and all my bones are coming apart.

My heart is like a piece of wax, melting inside my chest.

The roof of my mouth is as dry as a potsherd, and my tongue sticks to my palate;

You can consign me to the dust of death.

Dogs surround me; a gang of evildoers is closing in.

My hands and feet ache; I can count all my bones.

People stare and gloat over me; they divide my clothes among themselves,

and cast lots for pieces of clothing.

For my days pass away like smoke, and my bones burn like a furnace.

My heart is beaten down and withered like grass; I am too wasted to eat my bread.

Whenever I cry out in pain, my bones press up through my skin.

I am like an owl of the steppes, or a little owl perched in the ruins.

While I lie awake, I am like a lonely bird on a rooftop.

All day long my enemies taunt me; those who deride me use my name for a curse.

Ashes are my bread, and I mix tears with my drink, fleeing Your indignation and wrath.

For You have picked me up and thrown me away.

My days are like an evening shadow; I am withering like grass.

Quite unique as well is another standard element in prayers for help. They often feature a curious vow, in which the psalmist promises (or at least implies) that, if he is saved, he will devote himself to praising God forever more:

Have compassion on me, O LORD; consider my unbearable affliction and lift me up from the gates of death,

so that I may recount all Your praises; at Zion’s gates I will exult in Your salvation.

What is to be gained from my being silenced,19 my going down into the Pit?

Can dust praise You? Can it proclaim Your faithfulness?

Hear, O LORD, and have mercy on me . . .

So that I may sing Your praises and not be silenced, O LORD my God I will extol you forever.

Free me from my shackles, so that I may praise Your name—

Indeed, the righteous shall glory in it, if only You deal graciously with me.

These are not immutable requirements, as the classifiers sometimes imply.20 Nevertheless, the lesson is clear: the Psalms were not composed spontaneously, their authors having been moved by this or that event. Instead, they were apparently written to fit certain established categories, just as, in ancient Greece or Rome, poets wrote lyrics and epics and elegies and so forth. Not only were the different types of psalms and their basic forms standardized, but what they actually had to say, and how they went about saying it, was likewise the product of age-old conventions.

The Psalms and Ugaritic

If all this was fairly disturbing news for the traditional image of the Psalms, the twentieth-century discovery of a cache of texts from ancient Ugarit (above, chapter 24) was still more upsetting.

No collection of prayers or hymns was found in the library at Ugarit, but the texts that were discovered there nevertheless contained a great deal of material reminiscent of lines from the Psalms. It was not just a word or two, such as the already-mentioned appellation of Baal as the “cloud-rider” (rkb b‘rpt), echoed in the epithet of Israel’s God (rkb ‘rbt). Rather, the whole religious vocabulary of Ugarit, the way the denizens of this ancient city spoke of their gods and depicted their interaction, turned out to be strikingly reminiscent of elements in Israel’s own religion. As at Ugarit, so in the Psalms God was said to preside over a certain “assembly” of divine beings, angels or lesser deities—indeed, that assembly was called by the identical name (‘dt ’il[m]) in the Psalms and Ugaritic (see Ps. 82:1).21 The divine mercy so often appealed to in the Psalter turned out to be a standard characteristic of the god El at Ugarit. The sacrifices spoken of in the Psalms, and the temples that Gunkel and Mowinckel had hypothesized were the Psalms’ Sitz im Leben—these too had ready parallels at Ugarit.

Beyond these, the very style of Ugaritic poetry strikingly resembled that of the biblical Psalms. The same basic system of adjoining clauses (seen earlier in the Song of Deborah; chapter 23) was found to characterize Ugaritic prosody:

![]()

Moreover, the ways in which the connection between the clauses was established—omission of an essential word in clause B; repetition of the same word or phrase in A and B; the use of commonly paired words in A and B (“By day . . . by night”)—all were found in Ugaritic poetry; in fact, Ugaritic often featured the very same words that sealed the connection between adjacent clauses.22 One difference between Ugaritic poetry and most of that in the Psalter is that the Ugaritic poetic line does not nearly so regularly consist of only two clauses: often there are three or even more. In this feature it seems to share something with the Song of Deborah—not surprising, since, scholars say, that song is closer to Ugarit than most other biblical poems, both in time and in place of composition.

There are a few biblical psalms in particular that have an unmistakably Ugaritic sound. For example:

The voice of the LORD is over the waters; the God of glory thunders, the LORD, over mighty waters.

The voice of the LORD is powerful; the voice of the LORD is full of majesty.

The voice of the LORD breaks the cedars; the LORD breaks the cedars of Lebanon.

These lines reminded researchers of what was said of Baal in an Ugaritic epic:

Baal gives forth his holy voice, Baal repeats the utterance of his lips.

His holy voice [shatters] the earth.

[At his roar] the mountains quake, afar [ ] before Sea, the high places of the earth shake.

One of the most significant contributions of the Ugaritic texts (along with some literary texts from Mesopotamia) had to do with the meaning of specific words. Some of the things that people had always believed about words in the Bible—including, prominently, verses in the Psalms—turned out to be wrong. For example, the most common Hebrew word for soul, nefesh, means something a little less spiritual elsewhere in the Semitic world: throat or neck (as well as the desire connected with that part of the body, “appetite”). Thus, when the Psalmist cries out (to quote the old King James translation), “Save me, O God; for the waters are come in unto my soul” (Ps. 69:2), it turns out what he really meant was: the water is up to my neck! (Similarly, when the Israelites complain about the manna they got in the desert—“For there is no bread, neither is there any water; and our soul loatheth this light bread,” Num. 21:5 [KJV]—what they really meant was, “There is no bread and there is no water and our throats/appetites are sick of this miserable food.”) In other places, nefesh meant a person, oneself, so that “Bless the LORD, O my soul” might probably be translated more accurately as, “I will bless the LORD.” (Of course, nefesh sometimes does mean soul; indeed, sometimes, as in Ps. 42:1, the interplay between “soul” and “throat” is precisely the point.)

Another example: the Psalms are full of references to God’s “goodness,” or so scholars used to think. At least in some cases now, the word previously translated as “goodness” (![]() ob) ought probably to be understood more specifically—in keeping with a certain Ugaritic use of the cognate

ob) ought probably to be understood more specifically—in keeping with a certain Ugaritic use of the cognate ![]() b—as “[agricultural] plenty,” the result of ample rainfall; indeed, sometimes

b—as “[agricultural] plenty,” the result of ample rainfall; indeed, sometimes ![]() b itself appears to be a kind of code word for “rain.” So, for example, a verse that had once been translated as:

b itself appears to be a kind of code word for “rain.” So, for example, a verse that had once been translated as:

Yea, the LORD shall give that which is good; and our land shall yield her increase.

Ps. 85:13 (King James Version)

rather seems to mean that God “will give rain and our land shall yield her increase.” Similarly, since Psalm 84 describes the fate of the blessed in terms of plentiful water—“As they go through the valley of Baca they make it a place of springs; the early rain also covers it with pools” (Ps. 84:7)—it is not surprising that it should end by asserting:

The LORD will not withhold abundance [![]() ob] from those who walk uprightly.

ob] from those who walk uprightly.

Indeed, precisely the same expression, to “withhold/deprive t.ob,” appears when Jeremiah denounces his fellow Judahites:

They do not say in their hearts, “Let us fear the LORD our God, who gives the rain in its season,

the autumn rain and the spring rain, and keeps for us the weeks appointed for the harvest.”

It is your iniquities that have turned these away, and your sins have deprived you of t.ob.

Jer. 5:24–2523

Psalms Outside the Temple

An interesting thing happened within the biblical period: as time went on, the Psalms’ connection with the temple and the offering of sacrifices gradually weakened. They still had their place in the Jerusalem temple, of course, right down to the day in 70 CE when that temple was destroyed by the Romans. But long before, it appears, the Psalms had begun to take on a different role. Individuals, or perhaps groups of people, began to recite them outside of that cultic setting. Perhaps, some scholars theorize, this began as early as Josiah’s reform: once the Jerusalem temple became the only legitimate place for animal sacrifices, the other, provincial temples may nonetheless not have ceased to function; people might still have continued to go there to worship in some form—and to recite psalms.24 Whether that is true or not, certainly during the Babylonian exile (when there was no temple), reciting psalms may have functioned as the Jews’ main form of worship. Some of the latest psalms in the Psalter give every indication that they were never connected to cultic worship—they make no allusion to the accouterments of the temple, but instead speak of praising God “at all times” (Ps. 34:2) and “continually” (Ps. 145:1). A number of these late psalms are alphabetical acrostics (Psalms 34, 37, 111, 112, 119, 145), that is, each line or half-line or stanza starts with a succeeding letter of the alphabet. This arrangement seems to have been designed to help the individual worshiper remember the words—again, something that might suggest an intended setting outside the world of the temple and its professional choirs. The evidence is not altogether unambiguous, but it is difficult in any case to think of a long and repetitive psalm like Psalm 119 (176 verses) as having been intended for singing in the temple. Instead, this psalm appears to be a kind of litany in which repetition was the whole point. The individual worshiper may have gone through its great length as an act of piety, an offering made of words themselves.25

Eventually, of course, the connection with the Jerusalem temple was severed entirely. With that building in ruins after 70 CE, the Psalms became the exclusive property of the synagogue and the church—places where the faithful might gather and, without sacrificing animals on sacred altars, nonetheless offer praise and thanksgiving and prayers to God. Interestingly, these early liturgies did not limit themselves to psalms that were apparently composed for recitation outside the temple. Instead, the old temple psalms—with their evocation of coming “before God” and bowing down in “Your holy place”—were also recited. With time, apparently, their words had taken on a new meaning: one might come before God anywhere, and old prayers and thanksgiving might be uttered quite apart from their original context and meaning.

This historical fact is of great significance to the larger theme of this book, how we are to read the Bible today. For the case of the Psalms is, in miniature, the case of the whole Bible. We know now, better than ever before, what the Psalms originally meant and why they were written. But is that original meaning to be decisive? If, even within the biblical period, the Psalms came to mean something else—if people prayed the same words in a setting different from the intended one and with a different meaning, and if they have continued to do so for more than twenty centuries since—does it really matter that the original authors did not mean for their words to be used and understood in the way that we use and understand them?

This is not a question to be answered glibly. The insights of modern scholarship certainly have changed some things for worshipers, and probably will continue to do so. For example, despite the beauty of the old King James translation of Psalm 23, many modern Bibles have found themselves obliged to abandon its key elements: the basic understanding of the psalm as embodied in that seventeenth-century translation is no longer acceptable to modern scholars. Consider, for example, the psalm’s last line in the King James Version:

Surely goodness and mercy shall follow me all the days of my life: and I will dwell in the house of the LORD for ever.

At some point in this psalm’s history,26 the phrase “dwell in the house of the LORD for ever” came to be understood as a reference to life after death. This was in part because of the psalm’s earlier reference to walking “through the valley of the shadow of death”—that shadow extends over all the words that follow. (And if one walks through that valley, getting to its other side, this implies that one arrives at what lies beyond death.) Moreover, the psalm’s reference to dwelling “in the house of the LORD for ever” suggests an unlimited length of time, going on even after “all the days of my life” (mentioned in the previous clause) are over. So it was that Psalm 23 came to be taken as the psalm in the Psalter that holds out the clear hope for life after death; among other functions, it became a staple of funeral services.

Most contemporary scholars reject this understanding. To begin with, the “valley of the shadow of death” seems to be a misreading (and misdivision) of the original Hebrew text: “a very dark valley” or “valley of darkness” is closer to what the psalm really says.27 And it does not say “through” that valley; the Hebrew preposition means only “in.” As for the psalm’s last verse, the words translated as “for ever” really only mean “for a length of days” or “for a long time.” It seems more like a reaffirmation, rather than an extension, of “all the days of my life.” (That is why most modern translations render this phrase not as “forever” but “my whole life long” or the like.) As for “the house of the LORD,” everywhere else in the Hebrew Bible this means the temple. One certainly could not be buried in the temple and so dwell there after death: such corpse defilement would render the temple utterly unfit for God’s presence. Putting all this together, it seems that what the psalm originally meant was:

[Although things may at times be frightening, and] even though I might sometime be walking in a very dark valley, I will not be afraid . . . My only pursuers will be abundance and [divine] generosity my whole life long; and I will stay28 in God’s temple for a long time.

Which is the real Psalm 23?29 The one that talks about life after death, or the other one? And in a broader sense, what are we to think of the Psalms today, now that we know that, far from being the personal lyrics of King David, scribbled down by a prophetlike servant of God in time of trouble or celebration, they are mostly cultic pieces penned by anonymous temple functionaries, studded with conventional phrases and themes and worded in a one-size-fits-all vocabulary that was designed to give worshipers the feeling of specificity while equipping them for multiple reuse?

The answer to this question rests, to a surprising degree, with the person reading the Psalms and the context in which that reading takes place. Few modern readers will wish to put their hands over their ears and drone out the scholars in Göttingen and New Haven. “The truth as best we can know it” has a claim on every human heart, and in the case of the Psalter, it has changed forever the meaning of many of its words. At the same time, as some scholars have noted, the basic gesture of the psalms—as an offering of words parallel (if subordinate) to the offering of sacrifices—still survives today.30 People who recite the Psalms are still, in unmistakable fashion, offering up their time and their energy to God, subordinating themselves to Him in a concrete act of devotion and faithfulness. Even within the biblical period, this basic gesture survived the transition from the Israelite temple to other sites untroubled, and it continues to survive today.

Beyond this point, however, is another peculiarity of the Psalms. When someone reads the words of a psalm as an act of worship, he or she takes over, in a sense, the psalm’s authorship. It may have been written by an ancient Levite, but at the moment of its recitation, its words become the worshiper’s own: they speak on his or her behalf to God. There are few other cases I can think of in which such a total adoption of a text takes place. Even an ardent lover, reciting someone else’s poem (or singing someone else’s song) to the woman of his dreams never becomes the words’ new author in quite the same way; he identifies with the text, but both he and she are aware that what he is uttering is not his own composition, and this slight distance between himself and the author never quite disappears. Perhaps the only analogous case in the secular world is the taking of an oath: someone being sworn into the army speaks the words composed by someone else not as an act of quotation or even identification, but as if they were fully his own. So is it, too, with the Psalms. This seems to me a remarkable phenomenon, precisely because what is crucial are not the words themselves, but the mind of the worshiper who utters them. The very attitude of prayer pushes to the background the historical circumstances of the psalm’s composition. The true author is now the worshiper himself.31