Solomon’s Wisdom

2 SAMUEL 13 THROUGH 1 KINGS 4

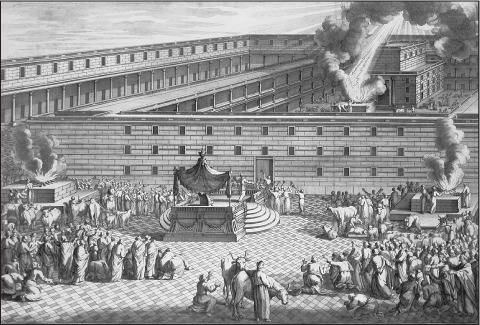

Feast of the Dedication of the Temple by Matthys Pool.

THE RAPE OF TAMAR AND ABSALOM’S REBELLION. ABISHAG THE SHUNAMMITE. SOLOMON MADE KING. SOLOMON’S WISDOM. ANCIENT NEAR EASTERN WISDOM. SOLOMON’S THREE BOOKS.

Solomon, David’s son, eventually succeeded him. God blessed him with wisdom surpassing that of any man. But if he was so wise, why did he make such a mess of his kingdom?

The oldest of David’s sons was Amnon, and he was thus slated to succeed David on the throne. But it did not turn out that way. Things started to unravel, the Bible reports, because of a beautiful girl, Tamar, who was Amnon’s half sister. (She was the full sister of Amnon’s younger brother Absalom.) Amnon could not stop thinking about Tamar. One day, his friend Jonadab told Amnon he was worried about him:

“Why do you look so bad, prince, morning after morning? Do you want to tell me about it?” Amnon said to him, “I am in love with Tamar, my brother Absalom’s sister.” Jonadab said to him, “Lie down on your bed, and pretend to be sick; then, when your father comes to see you, say to him, ‘Let my sister Tamar come and give me something to eat. Let her make the food herself, right here, so that I can see and then she can feed me.’”

It is not clear what exactly Jonadab’s plan was intended to lead to. As Amnon’s half sister, Tamar would not normally be required to avoid casual contact with him; they might even share a sibling embrace—so long as it was in public (Song 8:1). Her going unescorted into his bedroom would presumably be another matter, however, one that required a good excuse, which is why Amnon had to claim to be ill.

So Amnon lay down, and pretended to be sick; and when the king came to see him, Amnon said to the king, “Please have my sister Tamar come and make some cakes, right here, so that she can then feed them to me.” So David sent word to Tamar, saying, “Go to your brother Amnon’s house, and make some food for him.” Tamar went to her brother Amnon’s house, where he was in bed. She took dough, kneaded it, made cakes in front of him, and baked the cakes. Then she took the pan and set them out before him, but he did not eat. [Instead,] Amnon said, “Get everyone out of here.” So everyone left. Then Amnon said to Tamar, “Bring the food in here so that you can feed it to me.” So Tamar took the cakes she had made, and brought them into her brother Amnon’s room. But when she began to serve them to him, he grabbed hold of her and said to her, “Come, lie with me, my sister.” She said him, “No, my brother, no! Don’t force me! People don’t do that in Israel. Don’t do something so wrong! Where could I hide my shame? And you—you would be considered a common criminal in Israel. Talk to the king, I beg you; he won’t prevent you from [marrying] me.” But he would not listen to her; and since he was stronger than her, he took her by force and lay with her.

But then Amnon was seized with a great loathing for her; indeed, his loathing was even greater than the love he had felt for her before. Amnon said to her, “Get out!” But she said to him, “No, my brother! Sending me away now—that would be even worse than the other thing you did to me.” But he would not listen to her. He called his young servant and said, “Get her out of here, and lock the door after her.” (Now she was wearing an ornamented robe, since that was what the king’s virgin daughters used to wear as cloaks.) So his servant put her out, and locked the door after her. Then Tamar put ashes on her head and tore the ornamented robe75 that she was wearing; she put her hand on her head,74 and walked about, crying as she went.

When Absalom heard that his sister had been raped by Amnon, he said nothing to him about it, but secretly he was already planning his revenge. The opportunity came two years later. Amnon, by then suspecting nothing, accompanied Absalom to a sheep shearing (a festive event marked by eating and drinking). After Amnon had consumed a certain quantity of alcohol and was “merry with wine,” Absalom had his servants murder him. He then fled to the land of Geshur.

Absalom’s Rebellion

Fearing David’s wrath, Absalom stayed in exile in Geshur (his mother’s homeland) for three years. Eventually, with the help of a court insider (Joab, David’s nephew and general) and a certain “wise woman of Tekoa,” Absalom persuaded David to allow him to return to Jerusalem. But David was still angry at his son. It took two more years before the king even allowed Absalom to come to court to see him. But then David forgave him (2 Sam. 14:33).

What was on Absalom’s mind during his exile in Geshur? Apparently, the long wait there, along with David’s (temporary) blackballing of him after he returned, had started Absalom thinking. After all, he was David’s son, a potential heir to the throne. His good looks were legendary (2 Sam. 14:25), and, as we have seen, physical appearance certainly counted in the selection of a king (1 Sam. 9:2; 16:12). Part of Absalom’s beauty he owed to his long, flowing hair—so long and flowing that, when he got his annual haircut, the hair cut off would weigh two hundred shekels (about twice the weight of the wool produced by an average sheep at shearing!). And Absalom was in an excellent political position to succeed David. As the son of a Geshurite mother, he had some potential appeal to the northern tribes (since Geshur was on the far side of the Jordan right next to the eastern half of the tribe of Manasseh); as David’s son, he could also count on the southerners’ support. So why wait for David to decide on his successor? Absalom began winning allies for himself. He would buttonhole people who had come to the capital for a lawsuit and talk with each one personally: “Where are you from? What’s your case about?” Then he would seem to sympathize with their cause. “Too bad I am not the country’s judge! Then anyone who had a lawsuit would be able to come to me, and I would make sure he got justice” (2 Sam. 15:4). The person would usually start to bow down to him, but Absalom would grab him by the hand instead and embrace him.

After a time, Absalom invented a pretext that would allow him to travel to Hebron with two hundred of his supporters. When he got there he had himself proclaimed king, just as his father had done years earlier. Among those who joined Absalom’s cause was one of David’s top advisors, Ahitophel. This was a great coup on Absalom’s part; soon, people “throughout all the tribes of Israel” were backing him (2 Sam. 15:10). Absalom was now on his way. So great was the groundswell for this usurping son that David had to flee his own capital of Jerusalem, taking everyone except ten of his concubines, whom he left to look after the palace. Absalom moved right in and, on Ahitophel’s advice, set up a very visible tent on the palace roof, in which he had relations with David’s concubines—a demonstration that he was the de facto new king.

But David and his forces regrouped on the far side of the Jordan. On the brink of the confrontation between his army and his son’s, David seemed more worried about the fate of Absalom than the outcome of the fight: “Deal gently with my boy Absalom,” he warned his generals. Perhaps it was already obvious who would win. Although Absalom had ample men, apparently swelled by northern recruits, they were soon overcome by David’s seasoned soldiers. In all, twenty thousand men perished that day. As for Absalom, his long, flowing hair proved his undoing:

Absalom was riding on his mule, and the mule went under the thick branches of a great oak. His head caught fast in the oak, and he was left hanging between heaven and earth, while the mule that was under him went on. A man saw it, and told Joab [David’s general], “I saw Absalom hanging in an oak.” . . . [Joab] took three spears in his hand, and thrust them into Absalom’s heart while he was still alive in the oak. Then ten young men, Joab’s armor-bearers, surrounded Absalom and struck him, and killed him.

It did not take long for the news to reach David:

Then Joab said to a Cushite, “Go, tell the king what you have seen.” The Cushite bowed before Joab, and ran . . . Now David was sitting between the two gates. The sentinel went up to the roof of the gate by the wall, and when he looked up, he saw a man running alone . . . Then the Cushite came; and the Cushite said, “Good news for my lord the king! The LORD has taken your side today against all your enemies.” The king said to the Cushite, “Is my boy Absalom safe?” The Cushite answered, “May the enemies of my lord the king, and all who rise up to do you harm, end up like that boy.” . . . The king was shaken. He went up to the chamber over the gate, and as he went, he said, “Oh, Absalom my son! My son, my son Absalom! If only I could have died instead of you, Absalom. My son, my son!”

Measure for Measure

The details of Absalom’s rebellion once again cause scholars to wonder where this account came from. On the one hand, it has the hallmarks of a contemporaneous account. The portrait of a headstrong young man, perhaps resentful of his older half-brother from the start, and certainly even more so after the reported rape of Tamar (if indeed that was what happened and not an excuse invented after Amnon’s murder), a potential heir to the throne kept in exile by a king as wary of his son as he was angry at him—all this seems altogether plausible. So too is Absalom’s conduct prior to the open rebellion, slowly building a power base where David was weakest, with the northern tribes, then winning Ahitophel to his cause; this was truly a classic palace revolt.1 On the other hand, it is so well written and so engaging that at times it seems more like the work of an ancient writer of fiction—“a novel,” in the words of one scholar.2 In particular, the tension over Absalom’s fate in battle, the brutal description of his death, and then the pathetic picture of his father’s grief—all these have seemed to scholars to show a creative flair that is different from the cold, dispassionate recital of facts characteristic elsewhere of biblical historiography.

Needless to say, either judgment would be quite out of place in the period when the Bible was first becoming the Bible. The earliest interpreters of Scripture viewed the account of David’s struggles as they viewed everything else in the Bible. These stories, they felt, were certainly true recitations of the facts, but if they were included in God’s holy book it was because they contained some lesson applicable to their own—and our—daily lives. In this case, it did not require much scrutiny for interpreters to understand that God had arranged the events to convey the great principle of “measure for measure”—that is, God punishes or rewards people in keeping with their deeds, often designing the punishment or reward in such a way as to suggest a direct connection to its specific cause.

By the same measuring cup that a person measures out with, so is it measured back to him [by God] . . . Samson went after his own eyes [that is, followed his carnal desires], therefore Philistines plucked out his eyes, as it is said, “And the Philistines seized him and plucked out his eyes” (Judg. 16:21). Absalom was overly proud about his hair, therefore he got caught up by his hair. And since he had relations with his father’s ten concubines, therefore ten javelins were plunged into him, as it says, “ten young men, Joab’s armor-bearers, surrounded Absalom [and struck him, and killed him]” (2 Sam. 18:15). And since he deceived three different parties—his father, the courts,76 and all of Israel, [this last] because it is written, “And Absalom deceived the men of Israel” (2 Sam. 15:6)—therefore three spears pierced him, as it says, “He took three spears in his hand, and thrust them into the heart of Absalom” (2 Sam. 18:4).

m. Sotah, 1:7–8

A Warm Shunammite

After Absalom’s death, David still faced some rocky times—notably, a new revolt led by Sheba son of Bichri, from the tribe of Benjamin (which, however, David suppressed handily, 2 Samuel 20). But after that a new David emerged, one whose hold on power was unshakable. No one else rose up to challenge his rule, and his chief concern now was designating his successor, since David himself was growing old and weary.

It is at this point that the Bible reports on a troublesome physical problem faced by the king:

Now King David was old and advanced in years; and although they covered him with blankets, he could not get warm. So his servants said to him, “Let a young virgin be sought for His Majesty the king, and let her serve the king, and be his attendant; let her lie right next to you, so that my lord the king may be warm.” So they searched for a beautiful girl throughout all the territory of Israel, and found Abishag the Shunammite, and brought her to the king. The girl was very beautiful and she became the king’s attendant and served him, but the king was not intimate with her.

Here, certainly, was a creative solution to the problem of poor circulation caused by clogged arteries—though why exactly David’s bed warmer had to be a young and beautiful virgin is not explained. These qualities were to prove significant, however, for what happened next.

Adonijah was David’s oldest surviving son, and quite possibly considered his heir apparent. Like his late older brother Absalom, Adonijah was quite handsome (1 Kings 1:6) and eager to take over; he won a number of powerful supporters to his side. The prophet Nathan was not one of them, however, and when he learned that Adonijah had his eye on the throne, he persuaded Bathsheba to take the matter up with her husband, David. In fact, Nathan looks at this point to be a bit of a shady dealer. He tells Bathsheba to go to the king and “remind” him of a solemn oath that David had taken promising that Solomon, Bathsheba’s son with David, would be the next king. (The text seems to imply that there never was such an oath.) Nathan arranges to then enter the throne room and spontaneously confirm the existence of this oath. The plan works: David—probably addled by old age—is convinced that Solomon was indeed his promised heir, and he therefore has the priest Zadok anoint him as king (1 Kings 1:32–40). Shortly thereafter, David dies quietly in bed.3

So it was that Adonijah lost the kingship. He did, however, have one minor request of the new king. It was apparently a delicate matter, and so, rather than approach Solomon directly, Adonijah went to see Solomon’s mother, Bathsheba:

“There is something I wish to tell you,” he said. She said, “Go ahead.” He said, “You know that the kingship was supposed to be mine, and that all Israel had turned to me to be king. But the kingship has instead become my brother’s; it became his by the LORD’s will. What I want now is just one thing—do not refuse me.” She said to him, “Go ahead.” He said, “Please ask King Solomon—he will never refuse you—to give me Abishag the Shunammite as my wife.” Bathsheba said, “Very well; I will speak to the king about this.”

Adonijah’s request was ambiguous. It seems quite possible that all he really wanted was to marry Abishag. After all, she was young and beautiful; perhaps he had been smitten with her since the day she first came to the royal court. At the time, Adonijah probably expected to inherit her as soon as he became king—indeed, perhaps the two had even acted on this expectation during those times when she was not busy serving David or warming his bed. On the other hand, it may have been that, when he made this request for Abishag, Adonijah had not yet given up all hope of overthrowing Solomon. In ancient Israel, as we have seen, sleeping with the king’s wife or concubine was a de facto claim to the throne. (That is why Absalom had earlier made a point of sleeping with his father’s ten concubines.) If Adonijah could indeed end up with Abishag as his wife, he might at some later point claim that David himself had willed her to him—and hence that the kingship had really been promised to him.

Solomon chose to interpret his half-brother’s request in the latter sense. When Bathsheba told him what Adonijah was asking for, he exploded:

King Solomon said to his mother, “And why are you requesting only Abishag the Shunammite for Adonijah? You might as well ask for the kingship for him too! After all, he is my older brother—and he and the priest Abiathar and Joab son of Zeruiah [are in league together].”77 Then King Solomon swore by the LORD, “So may God do to me, and more so [if I don’t carry out this oath:] Adonijah will pay with his life for raising this matter! As the LORD lives, who has established me and placed me on the throne of my father David, and who has given him a dynasty as he promised, Adonijah will be executed this very day.” So King Solomon sent Benaiah son of Jehoiada; he struck him [Adonijah] down, and he died.

The Real Shunammite

With such brutality did the new king secure his place as David’s uncontested successor. Centuries later, however, interpreters had difficulty believing that God’s book had intended to instruct them in all the seamy dealings of Solomon’s first days on the throne. Surely, there must be a hidden message here too! Jerome had no difficulty discovering it.

In the seventieth year of his life, David, who had theretofore been a man of war, now was unable to keep warm because of the chills of old age. Therefore, a girl was sought throughout the land of Israel who might sleep with the king and warm his aged body: Abishag the Shunammite. Now, if you were to take Scripture literally, wouldn’t this seem to you to have been invented as some kind of farce, one of those Atellan comedies? The freezing old man is wrapped round and round with bedclothes but cannot be warmed except by the embrace of some young girl! Bathsheba was still around at the time, as were Abigail and the rest of his wives and concubines mentioned by Scripture, but all were apparently rejected as lacking heat: the old man could be warmed by the embrace of one girl alone. Abraham was much older than David, yet so long as Sarah was alive he didn’t go looking for another wife. Isaac was twice as old as David, but he never grew cold with Rebekah, even when she was old. I will not even mention those earlier men from before the Flood, whose limbs, I should say, were, after nine hundred years, not merely aged but almost decomposing—yet they did not seek out the embrace of young women. And certainly Moses, the leader of the people of Israel, was one hundred and twenty years old and never changed from his Sephora.

So who is this Shunammite, both a wife and a virgin, so fervid as to warm up a cold man, yet so holy as to not provoke a warmed one to lust?79 [She is a symbol of] Wisdom. “Get wisdom, and above all your possessions, get understanding . . .” [Prov. 4:7]. Even the name Abishag in its secret significance refers to wisdom, which is greater among the aged.78

Jerome, Letter 52 2–3

For Jerome, the whole story of Abishag is, like the rest of Scripture, fraught with symbolic meaning. In truth, David’s difficulties in getting warm were quite beside the point. What the Bible was saying in its own cryptic way was that, having spent his life as a fighter and a man of war, David in his last years sought to embrace wisdom and pursue the sorts of insights that are available only to those who have reached old age.

Solomon’s Dream

Shortly after he succeeded his father on the throne, Solomon was blessed with an extraordinary dream vision:

At Gibeon, the LORD appeared to Solomon in a dream by night; and God said, “Make a request—what can I give you?” And Solomon said, “You have been so kind with my father, Your servant David, because he acted faithfully toward You, in righteousness and integrity of heart. Moreover, You have maintained that great kindness to this day by granting him a son to sit on his throne. So it is, O LORD my God, that you have made me, Your servant, king in place of my father David. But I am a raw youth; I know nothing about being a leader. And Your servant finds himself in the midst of a people who, since You have chosen them, are so great and numerous that they cannot even be numbered or counted. Give Your servant therefore an understanding mind to rule over Your people; [make me] able to decide what is right and what is wrong. For who can govern this great people?”

It pleased the LORD that Solomon had asked for this. God said to him, “Because you requested this—you did not ask for long life or riches for yourself, or for the life of your enemies, but you asked for understanding to discern what is right—I hereby grant you what you have asked. I hereby give you a wise and discerning mind, such as no one like you before has had and no one who comes after you will. I am also granting you what you did not ask for, both wealth and glory your whole life long, such as no other king has had. I will also grant you a long life, if you walk in My ways and keep My laws and My commandments, as your father David did.” Then Solomon awoke; it had been a dream.

So it was that, in one night, Solomon became the wisest of kings.

This is one of those passages in the Deuteronomistic history in which modern scholars find the heavy hand of the editor; the vocabulary, as well as the idealization of wisdom, smack of Deuteronomy.4 Yet it seems unlikely to most scholars that Solomon’s association with wisdom was an invention of the Deuteronomistic historians.5 A passage usually thought to be somewhat older6 is similarly unstinting in its praise of Solomon’s wisdom:

God gave Solomon wisdom—knowledge in great measure and breadth of mind as vast as the sand on the seashore. Solomon’s wisdom was greater than that of all the peoples of the east and all the wisdom of Egypt. He grew wiser than anyone—wiser than Ethan the Ezrahite, and Heman, Calcol, and Darda, the sons of Mahol; his fame spread throughout all the surrounding nations. He spoke three thousand proverbs, and his songs numbered a thousand and five. He could speak of trees, from the cedar that is in the Lebanon to the hyssop that grows out of the wall; he could speak about animals, birds, reptiles, and fish. People came from all the nations to hear Solomon’s wisdom; they came from all the kings of the earth who had heard of his wisdom.

1 Kings 4:29–34 (Hebrew, 5:9–14)

It is in part on the basis of these two passages that tradition came to assign Solomon a crucial role. He was held to be the author of three of the Bible’s books: Proverbs, Ecclesiastes, and the Song of Songs. Indeed, this belief is still espoused today by many Jews and Christians, although modern scholars have advanced reasons for skepticism.

But if Solomon was indeed so wise, how did he end up making such a mess of things? Shortly after his son Rehoboam took over the throne, the northern tribes seceded from the great United Monarchy that David had cobbled together. We have seen how careful David himself had been to try to cultivate the favor of the northerners, establishing his capital at a midpoint between north and south and moving the (northern-associated) ark and its tent shrine to Jerusalem. How, then, did the the country’s unity collapse so quickly? To modern historians, it seems unlikely that poor Rehoboam should bear all the blame for the secession that occurred shortly after the beginning of his reign; surely his father Solomon was at least partly at fault.7

And, in fact, at the time they seceded, the northerners were not coy about the reason for their discontent: Solomon had taxed them nearly to death, they said. “Your father made our yoke too heavy. Lighten the hard work imposed by your father and his heavy yoke” (1 Kings 12:4). There was some obvious justice to this complaint: the biblical record reports that Solomon was a spendthrift of almost unbelievable proportions. He began by assembling a huge bureaucracy; then he kept his bloated payroll of civil servants happy with lavish banquets à la Louis XIV. Every day, the Bible says, he and his people consumed “thirty cors of choice flour, and sixty cors of meal, ten fat oxen, and twenty pasture-fed cattle, one hundred sheep, besides deer, gazelles, roebucks, and fatted fowl” (1 Kings 4:22–23). He also maintained a huge standing army, with “forty thousand stalls of horses for his chariots, and twelve thousand horsemen” (1 Kings 4:26); he also had fourteen hundred chariots, each of which was worth six hundred shekels of silver (1 Kings 10:26). By comparison, fifteen shekels in biblical times would buy you an ox or approximately two tons of grain; a ram sold for two shekels (Lev. 5:15).

Solomon was equally well stocked with wives; he is said to have married “the daughter of Pharaoh, [and] Moabite, Ammonite, Edomite, Sidonian, and Hittite women” in addition to his native-born wives and concubines, including “seven hundred princesses and three hundred concubines” (1 Kings 11:1, 3). Even allowing for a certain amount of exaggeration, this was an impressive harem. Inside Solomon’s palace:

The king also made a great ivory throne, and overlaid it with the finest gold. The throne had six steps. The top of the throne was rounded in the back, and on each side of the seat were arm rests and two lions standing beside the arm rests, while twelve lions were standing, one on each end of a step on the six steps. Nothing like it was ever made in any kingdom. All King Solomon’s drinking vessels were of gold, and all the vessels of the House of the Forest of Lebanon were of pure gold; none was of silver—it was not considered as anything in the days of Solomon. For the king had a fleet of ships of Tarshish at sea with the fleet of Hiram. Once every three years the fleet of ships of Tarshish used to come bringing gold, silver, ivory, apes, and peacocks.

It is sometimes said that Solomon greatly expanded trade and that that is what is responsible for both his lavish expenditures and his ability to pay for them. But that does not sit well with the biblical report of the northerners’ complaint. If there is any truth to the biblical account of Solomon’s wealth, it seems obvious that he overspent and overtaxed—breaking the most elementary rule in the book of political leadership. So why doesn’t the Bible remember him as a fool rather than the wisest of kings? Whence this great, and apparently ancient, reputation for wisdom?

To some modern scholars it appears more likely that Solomon’s connection to wisdom—if it has any historical basis—reflects the fact that he might have been a patron of wisdom rather than a particularly wise man himself.8 That is, in the course of his endless spending, he no doubt surrounded himself with advisors, both native and foreign-born sages who might help steer the ship of state. After all, such was simply expected of a great king. Just as today, government offices in Washington and Paris and London typically include legions of economic advisors, military attachés, foreign policy analysts, agronomists, environmentalists, sociologists, demographers, statisticians, and bean counters of all varieties, so too in ancient Egypt and Mesopotamia, a host of sages and counselors flocked to court to help guide the decisions of the king. So it was, according to some scholars, that Solomon first brought wisdom—in the persons of a group of sage advisors—to the former backwater of the Jerusalem hills. If so, scholars say, later tradition might naturally have come to associate him personally with the pursuit of wisdom. But as a political leader, Solomon did little to merit his “wise” label; on the contrary, he may have been one of the most foolish rulers of biblical times.

One specific incident attributed to Solomon does, however, bespeak a certain wisdom on the king’s part. According to the biblical account, two prostitutes at one point approached Solomon in a legal dispute. (As king, he had the authority to rule in such cases.) The two were roommates, and they had each given birth to a son a few days apart. Then, one of the babies died in the middle of the night. Each woman claimed that the living baby was hers.

Solomon considered the two women carefully and then summarized the facts as they had presented them:

“The one says, ‘My son is the one that is alive, and your son is dead’; while the other says, ‘Not so! Your son is dead, and my son is the living one.’” Then the king said “Fetch me a sword,” so they brought the king a sword. The king said, “Divide the live baby in two and give half to the one, and half to the other.” But the woman whose son was alive said to the king—because she was overcome with feelings for her son—“Please, my lord, let her have the live baby; don’t kill him!” The other woman said, “Let it be neither mine nor yours; divide it.” Then the king responded: “Give the first woman the live baby; do not kill it. She is his mother.” When all Israel heard of the verdict that the king had rendered, they stood in awe of the king, because they saw that he had divine wisdom in carrying out justice.

Modern readers usually think this story is pretty silly—who could be stupid enough to believe the king would actually “divide” the baby in two, killing it in the process? What is not mentioned in the text, however, is the legal principle according to which disputed property for which there is no clear record of ownership—a field, for example, or an unoccupied house—would most likely be divided equally among the disputants.9 No doubt Solomon uttered some legal mumbo-jumbo to that effect, enough at least to convince the two women under those stressful circumstances that he actually intended to apply that principle to this case. The other point worthy of mention is that Solomon does not actually pronounce on who is the baby’s real, biological, mother. In ancient Israel, as in more modern times, people were not always sane and certainly did not always react logically under pressure. No doubt it would have taken considerably more investigation to determine with certainty who the true mother really was. But it did not matter. Solomon does not say, “She is the true mother,” or the like, only, “She is the mother.” Whatever the biological relationship, this woman is the only one of the two fit to be given the responsibility for the child henceforth.

Wisdom in the Ancient Near East

The word “wisdom” is generally used in the Bible in a somewhat different sense from the one it has in English. In English it is used for the most part to describe a quality of mind—good judgment, discernment, sagacity, and the like. It sometimes had this meaning in Hebrew too, but for the most part “wisdom” referred to things known, knowledge.10 So, in the passage cited earlier, the assertion that Solomon was the wisest of men is immediately followed by the “proof” thereof: he knew a huge number of proverbs and could “speak of trees, from the cedar that is in the Lebanon to the hyssop that grows out of the wall; he could speak about animals, birds, reptiles, and fish” (1 Kings 4:33).

We tend to think of knowledge as an ever-growing body of information: each day, scientists discover new things about the universe and about ourselves. But to a denizen of the ancient world, knowledge was a fixed, utterly static set of facts, the unchanging rules that underlie all of reality as we know it. Those rules had been established since the world had been created; indeed, when the Bible asserts that God had created the world “with wisdom” (Prov. 3:19; Ps. 92:6–7; 104:24), what it means is that He had established it according to certain immutable patterns. Possessing wisdom thus meant knowing those rules, not only the rules that governed the natural world (Solomon’s knowledge of trees and animals, birds, reptiles, and fish), but the rules that governed the way people, both the righteous and the wicked, behaved and the way God treated them in consequence. God had created these rules and immutable patterns, but He did not publicize them; on the contrary, they often lay hidden beneath the surface of things. It was the job of sages to try to discover them and to pass their findings on to later generations. Not everything, of course, could be known; some things were too well hidden. But with dogged perseverance and after centuries of observation, much of the underlying set of rules that govern reality had indeed been discovered. To possess wisdom was therefore to master all that had been discovered of life’s underlying pattern.

This had been an ongoing, international effort.11 By the time biblical Israel came along, wisdom had already been pursued for centuries and centuries in ancient Egypt and Mesopotamia; indeed, if the same above-cited passage says of Solomon’s wisdom that it was greater than that of “all the peoples of the east and all the wisdom of Egypt,” it is because these easterners and Egyptians were, at the time, the gold standard of wisdom, the patrons of individual sages and the wisdom academies wherein they taught. A good part of the ancient Near Eastern texts excavated in Egypt and Mesopotamia consists of the writings of such sages. But what form did they adopt to publish their findings?

Someone who makes a discovery in the “hard sciences” today usually writes it up in an article and prints it in a scientific journal or on the Internet. Other sorts of modern sages—social scientists or scholars of the humanities—tend to put their ideas into still longer treatises, hefty tomes that are published by university presses. But in the ancient Near East, if you discovered something about how the world works, you had to package your insight in a form in which it could travel. So it was that the standard form of ancient wisdom was a simple, two-part sentence—the same two-part sentence that was seen earlier to be the basic unit of biblical poetry:

![]()

This two-part wisdom sentence was called in Hebrew a mashal (usually translated as “proverb”).12 Part of the skill involved in being a sage was the ability to take a complex idea and stick it into the six or seven words that the mashal typically comprised. The sense might not be immediately apparent, but if not, so much the better! After all, learning wisdom meant knowing how to look deeply into the words of a mashal, examining it and turning it over and over until its full sense had revealed itself. Only then could a person be said to have mastered it. Thus, when it says of Solomon that he “spoke three thousand proverbs, and his songs numbered a thousand and five,” what the Bible means was that he had mastered a huge number of meshalim (the plural of mashal) and thus possessed much of what humanity had been able to discover about the underlying rules that govern reality as we know it.

The Book of Proverbs

The first of the three books that Solomon is said to have written is the biblical book of Proverbs, and this name well describes its contents: thirty-one chapters of brief, two-part sentences that explain the underlying principles of the world. Many of these meshalim take the form of a comparison: Part A presents an image of some kind, and Part B presents the thing in life that the image explains. So, for example—to return to the theme of how a proverb has to be mastered before someone can truly be said to possess it—consider the following:

A thorn got stuck in a drunkard’s hand, and a proverb in the mouth of a fool.

It seems obvious that some sort of unfavorable comparison is being made here—but what exactly is the point? Modern drunkards may frequently be said to “feel no pain” or exhibit their bad temper or drive too fast (and indeed, many actually manage to do all three at the same time), but in ancient Israel drunkards were known mostly for their inability to keep their balance: they “stagger” and fall to the ground (Isa. 19:14; 24:20; Ps. 107:27; Job 12:25). So it is that in this mashal the drunkard in question has fallen to the ground and, groping about on all fours, has gotten a thorn or thistle stuck in his hand. This image sets up the comparison for Part B. In similar fashion—that is, quite by accident and through no personal virtue—a mashal may end up in the mouth of a fool, but the fact that he has acquired it, as it were, does not mean that he has actually learned its truth and internalized it. It just ended up with him by chance, with no more effort or conscious intention than that of the mindless drunkard. So just because you hear someone spouting words of ancient wisdom, this proverb asserts, don’t think that the person in question really understands what he is saying, and certainly not that he has taken that wisdom to heart. (The comparison of the proverb to a thorn in this verse is particularly apt, since a mashal in ancient Israel was often imagined to be something sharp or pointed that could guide people on the proper path, in the same way that a goad or pointed stick was used to guide an animal.)81

Here is another proverb that requires some contemplation before its full sense is revealed:

One who grabs a dog by the ears, a passerby who meddles in a dispute not his own.

Someone who grabs a dog by the ears is, in the biblical world of unfailingly nasty dogs, in trouble. He should have just let the dog go by. Now, as soon as he lets go, the dog will bite him; in fact, if he lets go of just one ear, the dog will surely try to wheel around and bite the hand that is still holding the other ear. So is it with the person who meddles in someone else’s quarrel. At first he was in no danger, but as soon as he butted in, he became a party to the dispute. Now he cannot extricate himself, and he certainly cannot side with one of the disputants without the other turning to attack him. Beside this point, the proverbist probably intended us to understand that although such meddling begins with the disputants’ ears—that is, the meddler seeks to be heard by them—in the end, he is going to get it from their mouths.

Of such proverbs is the book of Proverbs made. But did Solomon write them? The book actually refers to Solomon as the author in three different places (Prov. 1:1; 10:1; 25:1), but modern scholars believe these three verses are later, editorial additions. Like the book of Psalms, they say, Proverbs is actually a collection of smaller collections. The first of these, chapters 1–9, is a self-contained unit, which concludes with the assertion that personified Wisdom has now “built her house, she has hewn her seven pillars” (Prov. 9:1), perhaps corresponding to seven80 basic subunits in the preceding text.13 Other apparent subunits are 10:1–22:16; 22:17–24:34; chapters 25–29; chapters 30–31 (these last two chapters are actually openly attributed to sages other than Solomon). The fact that Proverbs is a collection of collections does not, of course, prove that Solomon did not write one or all of them. But the “all” option seems to scholars quite unlikely on linguistic and stylistic grounds; the mixture of different dialects and phases of Hebrew suggests different authors, most of them connected with periods and/or geographic areas other than Solomon’s. What is more, at least one section of Proverbs seems to be a translation or paraphrase of an older Egyptian text.14 Perhaps most telling of all is the anthological character of wisdom texts in general, including those of ancient Egypt or Mesopotamia.15 To be a sage was to know, not to compose. In a sense, wisdom’s true author was God or the gods; after all, the “ways of the world” that were wisdom’s bailiwick had been divinely established at the beginning of time and then merely discovered by different human beings. The sage’s job was thus to collect and transmit the received wisdom to those eager to study it; even if he wrote a book, it was for the most part a rewording of truths discovered long ago. And indeed, the apparent intention of the Bible’s mention of Solomon speaking “three thousand proverbs” is not that he composed them (although this is how the verse is sometimes mistranslated) but that he had mastered them.

Orthodox Wisdom

The two proverbs cited above have to do with the way humans behave—how some spout proverbs without understanding them, and how many people tend to meddle needlessly in the affairs of others. These are indeed the sorts of insights that one might arrive at through ordinary observation—they do not seem to betray any particular ideology. In fact, on the basis of everything that has been said so far, one would probably conclude that the pursuit of wisdom consisted mostly of such observed truths.

But this is not so. The world of wisdom was highly ideological (and idealistic). One element of the wisdom ideology has already been glimpsed: all sages believed in the existence of an underlying body of rules that determined reality. In other words, things do not just happen in this world; they happen according to certain set, eternal patterns, and in a sense, even God is subject to their rules. That is not the view one usually finds in the Bible. Elsewhere God reacts, decides to do one thing or another as a consequence of this or that event; sometimes He grows angry at what happens or is pleased or even changes His mind. Such ideas are foreign to the world of wisdom. In that world, certain things are simply inevitable. Thus, justice must always prevail in the end: the righteous must always be rewarded and the wicked must always be punished:

The house of the wicked will be destroyed, but the tent of the upright will flourish.

Along with this is the related notion that self-restraint and humility are destined to win out in the end. Thus, in the above proverb, it is no accident that the wicked live in a house while the upright live in a flimsy tent. But it doesn’t matter: despite their wealth, the wicked will end up badly, while the humble dwelling of the upright will ultimately prevail.

Indeed, one of the most telling features of Israelite wisdom is its consistent division of humanity into two opposite categories, the wicked versus the righteous (or, above, the “upright”).16 Proverb after proverb contrasts the way these two groups behave, and the way in which they are rewarded or punished by God. But surely this is ideology talking. In the real world, there are very few people who could be described as altogether righteous or altogether wicked; most of us are somewhere in the middle. That middle ground is never mentioned in orthodox wisdom: deep inside the soul, we must make absolute choices, and these ultimately stamp us as allying ourselves with one camp or another. Indeed, it is striking that this “wicked versus righteous” contrast is sometimes presented in terms of another set of opposites, the foolish versus the wise. Neither of these latter terms is used to describe a person’s mental capacities but rather the way of life that he or she chooses:

The heart of the wise seeks out knowledge, the mouth of the fool seeks out foolishness.82

The wise person is someone who treads the path of wisdom, learning its simple lesson of following the strait and narrow and seeking to live life in accordance with it; the fool, by contrast, may actually be a diabolical genius, but by having rejected wisdom’s lessons from his own life, he has allied himself with anti-wisdom (“foolishness”), immoral excess, and all of human vice.

The Book of Ecclesiastes

This brings us to the second biblical book attributed to Solomon. If the book of Proverbs is chock full of “orthodox wisdom,” the book of Ecclesiastes is in some ways its opposite.17 The speaker of the book is obviously someone learned in the ways of wisdom, but he is too down-to-earth to buy into some of wisdom’s lofty idealism:

The sayings of Koheleth, son of David, king in Jerusalem:

“So futile,” says Koheleth, “everything is so futile!”

What does a person ever net from all the effort he expends in this world?

One generation goes out and another comes in, but the earth stays the same forever.

The sun rises and the sun sets; then rushing back to its place, it rises again.

The wind blows to the south and then turns to the north,

it turns and turns as it goes—the wind—and goes back again by its turning.

All the rivers flow to the sea, but the sea is never full,

[because] to the source of the rivers’ flowing, there they flow back again . . .

There is no remembrance of former things, just as, with regard to the later things that will be,

they will have no remembrance either with those who will be after them.

Where orthodox wisdom sees virtues and vices, people getting ahead by dint of hard effort and modest self-restraint, the author of Ecclesiastes sees only futility—or, as his book’s opening words are sometimes translated, “vanity of vanities.”83 Orthodox wisdom holds that the righteous are ultimately rewarded and the wicked are punished, but this writer asserts the contrary:

I have seen everything in my fleeting days:

A righteous man may die despite his righteousness, while a wicked one lives on despite his wickedness.

So do not be too righteous or act too much the sage, lest you be destroyed.

(But do not be overly wicked or play the fool, lest you die before your time.)

Boorishness is exalted to great heights, while the worthy are set low.

I have watched slaves riding by on horseback, and princes walking on the ground like slaves.

The book of Ecclesiastes might best be described as a lover’s quarrel with orthodox wisdom. The author wishes things were indeed the way traditional sages claimed—he is truly a student of (and a lover of) ancient proverbs and their ideology. But somehow, he says, reality rarely seems to match wisdom’s claims.

This is not to say, however, that the entire book is one long protest against the wisdom ideology (as is, for example, the book of Job).18 Ecclesiastes accepts many of wisdom’s lessons: wisdom is better than folly (2:13), self-restraint better than self-indulgence. Indeed, this author is capable of wording a mashal as cleverly as the best of ancient sages:

A name is better than scented oil, and the day of death better than the day of one’s birth.

Part A is certainly undeniable. A person’s name—here the author means not only a person’s reputation, but the sum total of everything he or she does in life—is more precious than any material possession, even the $100–an-ounce anointing oil described above (chapter 26). But how can Part B be true? The day of a person’s death is almost always an occasion for sadness, and birth an occasion for rejoicing; in what way is death “better”?

As with every mashal, Parts A and B are related. So here, the point throughout is indeed the person’s name. When a baby is born, Ecclesiastes is saying, it has no name—quite literally—and even after it has been given one name or another, that name is essentially meaningless until the person has actually grown and begun to do things in life. Little by little, he or she becomes a person, first doing this, then that, until slowly that “name” begins to mean something, for good or for ill. Eventually, it is full of rich detail and nuance—as detailed and nuanced as the person’s own life. And like any nonmaterial thing, it is impervious to change; no one can steal someone else’s name, and it will not erode or wash away. Meanwhile, that same person’s physical existence has started down the long path of decline that is the lot of all humans. In a physical sense, we are all like the precious anointing oil of Part A: what was very valuable at first begins to lose its savor, and sooner or later the whole vial will be used up or go bad and have to be disposed of. That day, the day of a person’s death, is certainly a sad day, but it is no less a day of great significance, since it marks the completion of the process of building a name. One can now take a step backward and contemplate (as one could not before) the whole person. In the end, each of us becomes our name; this is all that survives the dissolution of our “precious oil,” our physical selves. But, says Ecclesiastes, since you agree with Part A—a name is indeed better than precious oil—then you must also agree with Part B.

Did Solomon write any of this? Here too modern critics are skeptical. To begin with, the book contains two words that were not originally Hebrew but Persian: pardes (an enclosed orchard or garden, Eccles. 2:5) and pitgam (a royal decree, Eccles. 8:11). Loan words enter a language when two different civilizations have some ongoing, sustained contact. It was only after the British colonized India in the nineteenth century that Indian words like pundit, shampoo, jungle, and juggernaut entered the English language. A period of sustained contact between Persia and ancient Israel did not occur until long after Solomon’s time: in the late sixth century bce, four hundred years after his death, Persia began to rule over Israel’s remnant, the inhabitants of Judah, and it continued to rule over them for the next three centuries. That is the period when these and other Persian words first entered the language. One could of course say that Solomon, being the wisest of kings, had studied Persian on his own. But why would he use a word that no one else in his kingdom would understand for the next four hundred years? If King Henry VIII had suddenly started talking about pundits and shampoos, who in sixteenth-century England would have known what he was saying? Quite apart from these loan words, however, the whole dialect in which Ecclesiastes is written is markedly different from the classical Hebrew of earlier times—no serious student of Hebrew could confuse the two.19

In fact, the author of Ecclesiastes does tell us his name (or nickname): Koheleth (more properly transcribed as Qohelet). It probably comes from a late meaning of the root qhl, “argue” or “reprove.”20 He is thus the Arguer. His full name—Koheleth son of David—probably indicates that he was a descendant (though not literally the son) of David, a fact of which he was no doubt justly proud. That may also have something to do with the office that he says he occupied: he describes himself as “king” over Israel in Jerusalem (1:1, 12). Perhaps this is in fact how he presented himself (or was known) to his own people, but we would more likely describe him as a governor, since any Judean ruler at the time would have been altogether subject to the Persian authorities.

Long after the book was written, this mention of “Koheleth son of David” (like the phrase “to David” in the Psalms headings) took on a different look. If the author of the book described himself as the son of David who ruled over Israel in Jerusalem, well, that could only mean that he was literally David’s son and successor, King Solomon. Perhaps indeed, people theorized, Solomon had decided for one reason or other to refer to himself in this book by the name Koheleth.21 This attribution to Solomon ultimately proved highly significant. Certainly, from the standpoint of the ideas it contains, Ecclesiastes borders on the heretical. How was a religious Jew or Christian to understand bits of advice like “Do not be too righteous”? Moreover, ancient readers were troubled by the frequent contradictions and about-faces in the book.22 But if Ecclesiastes was indeed written by Solomon, the man to whom God granted greater wisdom than any other mortal, then surely every word of it was precious; its place in the canon was secure.

The Song of Songs

The third book attributed to Solomon’s authorship, the Song of Songs (also called the Song of Solomon or Canticles), seems even less likely to have been written by him. At times its Hebrew seems as late as that of Ecclesiastes, with Persian and perhaps even Greek borrowings (although it has also been suggested that different parts of the work date to different periods). Solomon may be named as the author in the editorial title, but the mythic king also appears twice in the body of the Song (3:9, 11; 8:12) as a third-person character, neither time presented in a particularly sympathetic light.

Moreover, the Song does not, at first glance, have anything to do with the world of wisdom. It seems to be all about love—and not love in the ethereal abstract, but love between a certain young man and a specific young woman, who are desperately, messily, deliriously, taken with each other. That is all the Song talks about. “Let him give me some of his kisses to drink,”23 the woman begins dreamily, “since love is sweeter than wine!” (Song 1:2). Speaking in a decidedly northern dialect (whether real or imitation),24 these two main figures stand in stark contrast to the sophisticated “Jerusalem girls” who appear here and there in the Song. Those young women—pale city dwellers from the distant south—are the polar opposite of the beautiful, tanned mountain girl of the Song. So it is probably no accident that, in one of their appearances, the Jerusalem girls are dazzled by the arrival of King Solomon in all his royal pomp (Song 3:11). How wrong it is for people to care about such things, the Song seems to say (cf. 8:7, 11–12); money and fancy possessions are meaningless. Love is the only thing in life that matters.

You are so beautiful, my love, your eyes like doves behind a veil—

and the way your hair hangs down, like herds come down from Gilead,

with your teeth as white as ewes freshly washed in a brook . . .

Your lips are like a crimson thread, and your mouth is so sweet,

your face like ripened fruit behind your veil,

your neck like David’s tower, fashioned to perfection,

with a thousand shields hung around it, the bucklers soldiers carry.

Your two breasts are like two fawns, twins grazing in the lilies.

Before the day drifts off and the shadows flee,

I’ll find my way to Spice Mountain, the fragrant hill.

Everything about you is beautiful, there’s not one thing that’s not.

Modern scholars see the Song as part of the great ancient Near Eastern tradition of love poetry, with its conventional descriptions of the lovers’ physical beauty and its frank exaltation of eroticism. Indeed, if we read through its light veil of metaphor, the Song is sometimes shockingly graphic in its description of the couple’s embraces. Perhaps, like certain similar ancient Mesopotamian or Egyptian poems, this one was created to be sung at wedding celebrations (although the Song contains not a word about the couple’s recent or upcoming marriage), containing equal measures of encouragement and instruction. Its refrain is “Give me your word, Jerusalem girls, and don’t start up, don’t get started with love until it’s time” (2:7; 3:5; 8:4). The Song certainly came to be associated with weddings in later days;25 however, the original purpose of its composition remains the subject of debate.26

What is this Song doing in the Bible? From early times, apparently, it came to be read as an allegory of the love between God and His people.27 After all, its lush language was often highly metaphorical; why not read the metaphors a little differently, as if they referred to the yearnings, the consummations and frustrations, of the love that joins human beings with the divine? Frustration plays no small part in the Song: “I called to him, but he did not answer” is a frequent theme (Song 5:6; cf. 1:7; 3:1; 6:1). Is this so different from the Psalmist’s frustration: “I’ve called out with all my heart—answer me, O LORD” (Ps. 119:145)? And if the Song raises love itself to the very summit of human existence—

Keep me as a locket on your heart, a signet on your arm.

For love is as strong as death, and as harsh as Sheol.

Its flames burn like a fire, a holy conflagration.

Deep waters can’t put it out, and rivers will not drown it.

If a man gave all his family’s wealth for love, would anybody blame him?

—then perhaps it really is just one long metaphor, its real subject the love between man and God.

• • •

Once, a bearded sage heard an old American song:

She’ll be comin’ round the mountain when she comes.

She’ll be comin’ round the mountain when she comes.

She’ll be comin’ round the mountain, she’ll be comin’ round the mountain,

She’ll be comin’ round the mountain when she comes.

She’ll be drivin’ six white horses when she comes.

She’ll be drivin’ six white horses when she comes.

She’ll be drivin’ six white horses, she’ll be drivin’ six white horses,

She’ll be drivin’ six white horses when she comes.

Oh, we’ll all come out to meet her when she comes . . .

We will kill the old red rooster when she comes . . .

Oh, we’ll all have chicken and dumplings when she comes . . .

We’ll all be shoutin’ Hallelujah when she comes . . .

“Do you think,” he asked, “that this song is talking about a real woman? Why should one person need six white horses? No, it is talking about the messianic age, when God’s earthly presence—always referred to as she28—will once again reappear, rounding the corner of Mount Zion. The six white horses are a token of the Messiah’s colt, mentioned by the prophet [Zech. 9:9], and if the song speaks of six it is because all this will come to pass in sixty years. Then everyone will be gathered from the earth’s four corners to welcome the event. As for the old red rooster, this is the rooster Ziz [Ps. 50:11], companion of Leviathan, symbol of evil; both will be killed in the end of days to make the messianic meal—these are the chicken and dumplings—as tradition long ago foretold.29 Then Hallelujah will ring from every quarter.”

That is what he said, and soon everyone was singing the old song—but now, its meaning was completely different. The words had not changed in the slightest, but what they meant had been transformed utterly. Henceforth no one could think of the old song the same way.

• • •

In one way, the Song of Songs is the most important biblical book to be dealt with in the present volume, since it poses most squarely the question of original meaning. If biblical texts mean only what they meant when they were first composed, then why should we still include the Song of Songs in the Bible? According to modern scholars, its words originally had nothing to do with God; they are no different from the love lyrics of ancient Egypt. True, people were misled for a while. Rabbi Akiba of the second century CE declared that “the whole world altogether is not as worthy as the day on which the Song of Songs was given to Israel,”30 and Christian interpretations—from the homilies and commentary written on the Song by the early exegete Origen (ca. 185–254 CE) to the eighty-six (!) sermons on it by Bernard of Clairvaux (1090–1153) and beyond—show the extent to which their authors exhausted themselves in attributing to it all sorts of hidden meanings. But now that we know what the Song is really talking about, we ought to have no further use for it; indeed, we ought to protect the delicate minds of children from exposure to its sometimes too easily deciphered metaphors.

Unless . . . Unless a text’s original meaning is not necessarily its meaning for ever and ever. This is a disturbing idea, of course; the whole point of writing something down is to put it into fixed form that will last—presumably unchanged. But sometimes things happen that do change the meaning of a text, or of any artifact. A photograph of the World Trade Center in New York came to mean something very different after September 11, 2001. The photographer who took it probably thought little about what he was doing at the time. For him it was a big building; that is why, shooting it from a certain angle, he sought to emphasize its great height and the sweep of its lines. But who can look at his photograph today and see what he saw, just another New York skyscraper? For most people nowadays, the photograph instantly stirs up memories. Peering into the picture’s details, some people must now, willy-nilly, see a deeper meaning—in fact, more than one. To some, the picture may embody the frailty of orderly civilization in the face of terrorism; to others, it has became a symbol of an earlier era, a time of self-confidence and peaceful ease; to still others, it now stands for America’s intolerable arrogance, justly struck down by God’s holy martyrs. But whatever the photograph now means, that meaning is quite different from the one originally intended by the photographer. All he thought he was doing was taking a picture of a tall building (which he was).

Someone like the bearded sage a few paragraphs ago heard in the Song of Songs a message that had probably not been intended by its original author. In a sense, one might think of him as the Song’s second author. He did not change a word, but he utterly transformed what the Song meant. “Listen to it my way,” he said, “and it’s not about a man and a woman at all.” He probably never claimed that this was what the Song had been composed to mean, only that one could understand it that way; and people agreed. Soon they were singing it and winking to each other—“Get it?” This was how the Song of Songs became part of Holy Scripture. Then, after a while, the winking stopped: the religious meaning became the only meaning.

In a sense, what happened with the Song of Songs is what happened with all of Scripture. Psalms that had been meant to be recited in the temple as an accompaniment to sacrifices came to be recited at home or in synagogue or church. In the process, the Psalmist’s “I bow down before You” changed its meaning. It no longer denoted a cultic act, “I bow down before the Holy of Holies where You, O God, are said to be enthroned,” but was now a non-cultic turning to the omnipresent deity, “I acknowledge You to be everywhere.” At roughly the same time, the story of Abraham also changed. “Read it my way,” a clever exegete must have said, “and it will be seen to recount the life of a sorely tried model of virtue, the world’s first monotheist. That is what I interpret Josh. 24:3 to mean, and this will explain its otherwise troubling non sequitur, ‘So I took Abraham . . .’” In this same period, a story about the transition from a hunter-gatherer society to an agricultural one also came to be interpreted differently; it now might be understood to contain a hidden message, an explanation for human mortality and sinfulness, indeed, the “Fall of Man.” Soon it was found that Jacob did not actually lie to his father; you just had to put in the right punctuation. Not long after, David’s Shunammite bed warmer became a symbol of wisdom and Rahab stood for the church of reformed sinners. Some of these changes may have been accompanied by a little wink, but soon the winks disappeared.

Without these changes, would there ever have been a Bible? That seems most unlikely. Why should anyone seeking to worship God devote himself or herself to reading the etiological narratives and political self-puffery of a civilization long dead, the guerrilla tactics and court shenanigans of various ancient kings, law codes endorsing ![]() erem and the stoning of a rebellious child, or statutes forbidding Molech worship and similarly outdated concerns, psalms specifically designed to accompany the sacrificing of animals at a cultic site, or erotic love poetry? All of these texts underwent a radical change in meaning when they began to be interpreted in the somewhat quirky, highly creative, and altogether God-centered approach of ancient scholars in the late biblical period. The original meaning of these texts disappeared. In a sense, ancient interpreters rewrote every one of them, even though they did not change a word.

erem and the stoning of a rebellious child, or statutes forbidding Molech worship and similarly outdated concerns, psalms specifically designed to accompany the sacrificing of animals at a cultic site, or erotic love poetry? All of these texts underwent a radical change in meaning when they began to be interpreted in the somewhat quirky, highly creative, and altogether God-centered approach of ancient scholars in the late biblical period. The original meaning of these texts disappeared. In a sense, ancient interpreters rewrote every one of them, even though they did not change a word.

The question that poses itself to today’s readers is: can we still read the Bible with the approach and assumptions that these ancient interpreters brought to it, even though modern biblical scholarship has now convinced many people that this way of reading is quite out of keeping with the original meaning of the text? Or (to refine the question a bit), if you and I now know a little too much to espouse that old way of reading naïvely and unquestioningly, can we somehow nevertheless manage to espouse it as what the Bible (as distinguished from its original, constituent parts) means? Indeed, can we hold both old and new together in our heads, perhaps recalling a hypothetical “Read it my way . . .” and a wink?