2

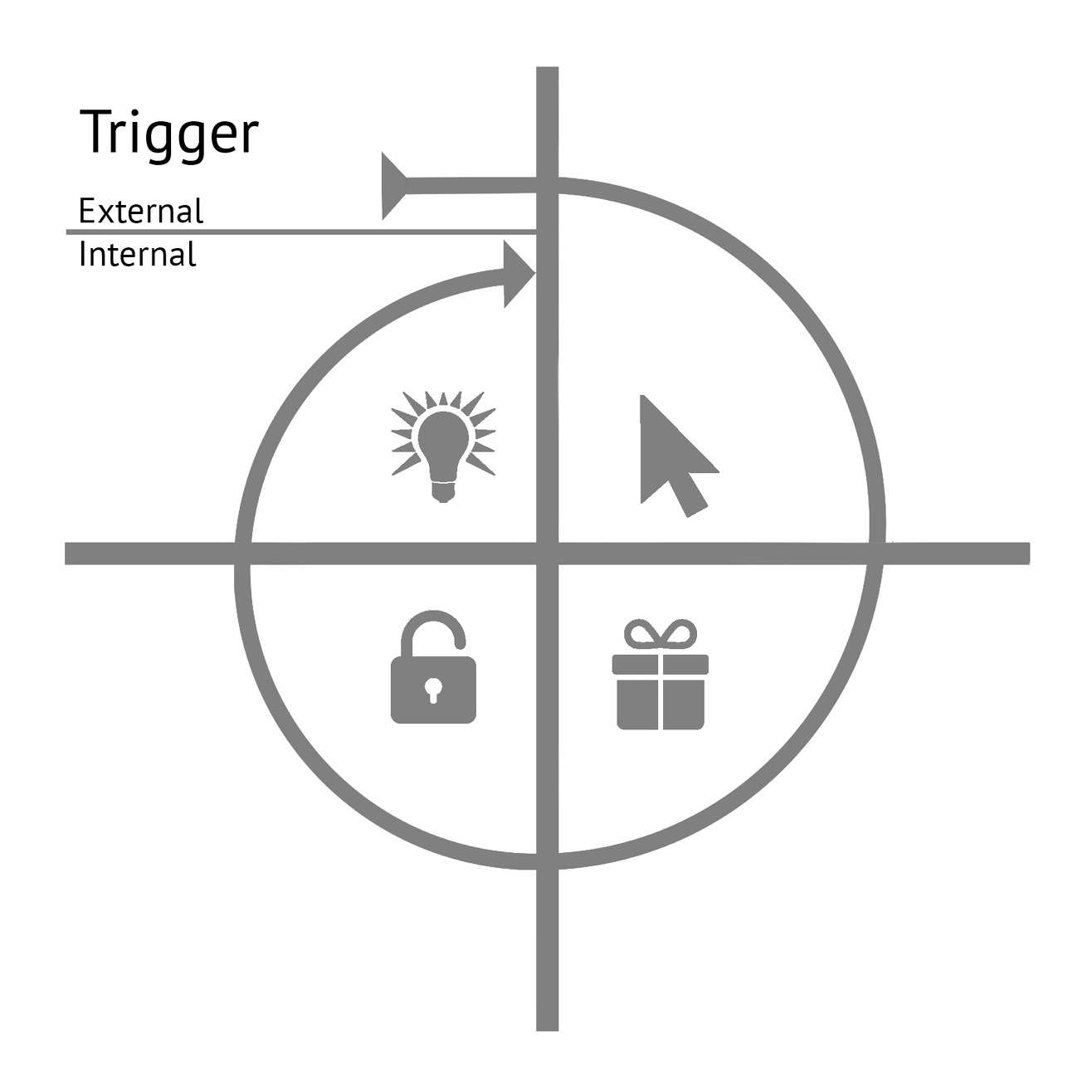

Trigger

Yin (not her real name) is in her mid-twenties, lives in Palo Alto, California, and attends Stanford University. She has all the composure and polish you’d expect of a student at a prestigious school, yet she succumbs to a persistent habit throughout her day. She can’t help it; she is compulsively hooked on Instagram.

The photo- and video-sharing social network, purchased by Facebook for $1 billion in 2012, has captured the minds and attention of Yin and 150 million other users like her.1

The company’s acquisition demonstrates the increasing power of—and immense monetary value created by—habit-forming technology.

Naturally, the Instagram purchase price was driven by a host of factors, including a rumored bidding war for the company.2 But at its core Instagram is an example of an enterprising team—conversant in psychology as much as technology—that unleashed a habit-forming product on users who subsequently made it a part of their daily routines.3

Yin doesn’t realize she’s hooked, although she admits she regularly snaps and posts dozens of pictures per day using the app. “It’s just fun,” she says as she reviews her latest collection of moody snapshots filtered to look like they were taken in the late 1970s. “I don’t have a problem or anything. I just use it whenever I see something cool. I feel I need to grab it before it’s gone.”

What formed Yin’s Instagram habit? How did this seemingly simple app become such an important part of her life? As we will soon learn, habits like Yin’s are formed over time, but the chain reaction that forms a habit always starts with a trigger.

HABITS ARE NOT CREATED, THEY ARE BUILT UPON

Habits are like pearls. Oysters create natural pearls by accumulating layer upon layer of a nacre called mother-of-pearl, eventually forming the smooth treasure over several years. But what causes the nacre to begin forming a pearl? The arrival of a tiny irritant, such as a piece of grit or an unwelcome parasite, triggers the oyster’s system to begin blanketing the invader with layers of shimmery coating.

Similarly, new habits need a foundation upon which to build. Triggers provide the basis for sustained behavior change.

Reflect on your own life for a moment. What woke you up this morning? What caused you to brush your teeth? What brought you to read this book?

Triggers take the form of obvious cues like the morning alarm clock but also come as more subtle, sometimes subconscious signals that just as effectively influence our daily behavior. A trigger is the actuator of behavior—the grit in the oyster that precipitates the pearl. Whether we are cognizant of them or not, triggers move us to take action.

Triggers come in two types: external and internal.

External Triggers

Habit-forming technologies start changing behavior by first cueing users with a call to action. This sensory stimuli is delivered through any number of things in our environment.

External triggers are embedded with information, which tells the user what to do next.

An external trigger communicates the next action the user should take. Often, the desired action is made explicitly clear. For example, what external triggers do you see in this Coca-Cola vending machine in figure 2?

Take a close look at the welcoming man in the image. He is offering you a refreshing Coke. The “Thirsty?” text below the image tells you what the man in the photo is asking and prompts the next expected action of inserting money and selecting a beverage.

FIGURE 2

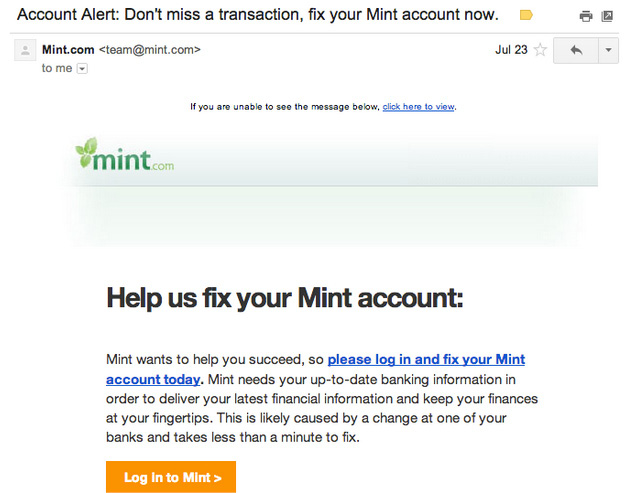

Online, an external trigger may take the form of a prominent button, such as the large “Log in to Mint” prompt in the e-mail from Mint.com in figure 3. Here again, the user is given explicit instructions about what action to take after reading the e-mail: Click on that big button.

Notice how prominent and clear the intended action is in the e-mail from Mint? The company could have included several other triggers such as prompts to check your bank balance, view credit card deals, or set financial goals. Instead, because this is an important account alert e-mail, Mint has reduced the available actions to a single click: logging in to view and fix your account.

FIGURE 3

More choices require the user to evaluate multiple options. Too many choices or irrelevant options can cause hesitation, confusion, or worse—abandonment.4 Reducing the thinking required to take the next action increases the likelihood of the desired behavior occurring unconsciously. We’ll explore this further in the next chapter.

The Coca-Cola vending machine and Mint.com e-mail provide good examples of explicit external triggers. However, external triggers can also convey implicit information about the next desired user action. For example, we’ve all learned that Web site links are for clicking and app icons are for tapping. The only purpose for these common visual triggers is to prompt the user to action. As a readily accepted aspect of interface design, these calls to action don’t need to tell people how to use them; the information is embedded.

Types of External Triggers

Companies can utilize four types of external triggers to move users to complete desired actions:

1. Paid Triggers

Advertising, search engine marketing, and other paid channels are commonly used to get users’ attention and prompt them to act. Paid triggers can be effective but costly ways to keep users coming back. Habit-forming companies tend not to rely on paid triggers for very long, if at all. Imagine if Facebook or Twitter needed to buy an ad to prompt users to revisit their sites—these companies would soon go broke.

Because paying for reengagement is unsustainable for most business models, companies generally use paid triggers to acquire new users and then leverage other triggers to bring them back.

2. Earned Triggers

Earned triggers are free in that they cannot be bought directly, but they often require investment in the form of time spent on public and media relations. Favorable press mentions, hot viral videos, and featured app store placements are all effective ways to gain attention. Companies may be lulled into thinking that related downloads or sales spikes signal long-term success, yet awareness generated by earned triggers can be short-lived.

For earned triggers to drive ongoing user acquisition, companies must keep their products in the limelight—a difficult and unpredictable task.

3. Relationship Triggers

One person telling others about a product or service can be a highly effective external trigger for action. Whether through an electronic invitation, a Facebook “like,” or old fashioned word of mouth, product referrals from friends and family are often a key component of technology diffusion.

Relationship triggers can create the viral hyper-growth entrepreneurs and investors lust after. Sometimes relationship triggers drive growth because people love to tell one another about a wonderful offer.

For example, it is hard to top PayPal’s viral success of the late 1990s.5 PayPal knew that once account holders started sending other users money online they would realize the tremendous value of the service. The allure that someone just sent you money was a huge incentive to open an account, and PayPal’s growth spread because it was both viral and useful.

Unfortunately, some companies utilize viral loops and relationship triggers in unethical ways: by deploying so-called dark patterns. When designers intentionally trick users into inviting friends or blasting a message to their social networks, they may see some initial growth, but it comes at the expense of users’ goodwill and trust. When people discover they’ve been duped, they vent their frustration and stop using the product.

Proper use of relationship triggers requires building an engaged user base that is enthusiastic about sharing the benefits of the product with others.

4. Owned Triggers

Owned triggers consume a piece of real estate in the user’s environment. They consistently show up in daily life and it is ultimately up to the user to opt in to allowing these triggers to appear.

For example, an app icon on the user’s phone screen, an e-mail newsletter to which the user subscribes, or an app update notification only appears if the user wants it there. As long as the user agrees to receive a trigger, the company that sets the trigger owns a share of the user’s attention.

Owned triggers are only set after users sign up for an account, submit their e-mail address, install an app, opt in to newsletters, or otherwise indicate they want to continue receiving communications.

While paid, earned, and relationship triggers drive new user acquisition, owned triggers prompt repeat engagement until a habit is formed. Without owned triggers and users’ tacit permission to enter their attentional space, it is difficult to cue users frequently enough to change their behavior.

• • •

Yet external triggers are only the first step. The ultimate goal of all external triggers is to propel users into and through the Hook Model so that, after successive cycles, they do not need further prompting from external triggers. When users form habits, they are cued by a different kind of trigger: internal ones.

Internal Triggers

When a product becomes tightly coupled with a thought, an emotion, or a preexisting routine, it leverages an internal trigger. Unlike external triggers, which use sensory stimuli like a morning alarm clock or giant “Login Now” button, you can’t see, touch, or hear an internal trigger.

Internal triggers manifest automatically in your mind. Connecting internal triggers with a product is the brass ring of consumer technology.

For Yin, the young woman with the Instagram habit, her favorite photo app manufactured a predictable response cued by an internal trigger. Through repeated conditioning, a connection was formed between Yin’s need to capture images of the things around her and the app on her ever-present mobile device.

Emotions, particularly negative ones, are powerful internal triggers and greatly influence our daily routines. Feelings of boredom, loneliness, frustration, confusion, and indecisiveness often instigate a slight pain or irritation and prompt an almost instantaneous and often mindless action to quell the negative sensation. For instance, Yin often uses Instagram when she fears a special moment will be lost forever.

The severity of the discomfort may be relatively minor—perhaps her fear is below the perceptibility of consciousness—but that’s exactly the point. Our life is filled with tiny stressors and we’re usually unaware of our habitual reactions to these nagging issues.

Positive emotions can also serve as internal triggers, and may even be triggered themselves by a need to satisfy something that is bothering us. After all, we use products to find solutions to problems. The desire to be entertained can be thought of as the need to satiate boredom. A need to share good news can also be thought of as an attempt to find and maintain social connections.

As product designers it is our goal to solve these problems and eliminate pain—to scratch the user’s itch. Users who find a product that alleviates their pain will form strong, positive associations with the product over time. After continued use, bonds begin to form—like the layers of nacre in an oyster—between the product and the user whose need it satisfies.

Gradually, these bonds cement into a habit as users turn to your product when experiencing certain internal triggers.

A study at the Missouri University of Science and Technology illustrates how tech solutions can provide frequent psychological relief.6 In 2011 a group of 216 undergraduates volunteered to have their Internet activity anonymously tracked. Over the course of the academic year, the researchers measured the frequency with which these students used the web and what they were doing online.

At the end of the study, the researchers compared anonymous data of students who visited the university’s health services to treat symptoms of depression. “We identified several features of Internet usage that correlated with depression,” wrote Sriram Chellappan, one of the study’s authors.7 “For example, participants with depressive symptoms tended to engage in very high e-mail usage . . . Other characteristic features of depressive Internet behavior included increased amounts of video watching, gaming, and chatting.”

The study demonstrated that people suffering from symptoms of depression used the Internet more. Why is that? One hypothesis is that those with depression experience negative emotions more frequently than the general population and seek relief by turning to technology to lift their mood.

Consider, perhaps, your own emotion-cued behaviors. What do you do in response to your internal triggers?

When bored, many people seek excitement and turn to dramatic news headlines. When we feel overly stressed, we seek serenity, perhaps finding relief in sites like Pinterest. When we feel lonely, destinations like Facebook and Twitter provide instant social connections.

To ameliorate the sensation of uncertainty, Google is just a click away. E-mail, perhaps the mother of all habit-forming technology, is a go-to solution for many of our daily agitations, from validating our importance (or even our existence) by checking to see if someone needs us, to providing an escape from life’s more mundane moments.

Once we’re hooked, using these products does not always require an explicit call to action. Instead, they rely upon our automatic responses to feelings that precipitate the desired behavior. Products that attach to these internal triggers provide users with quick relief. Once a technology has created an association in users’ minds that the product is the solution of choice, they return on their own, no longer needing prompts from external triggers.

In the case of internal triggers, the information about what to do next is encoded as a learned association in the user’s memory.

The association between an internal trigger and your product, however, is not formed overnight. It can take weeks or months of frequent usage for internal triggers to latch onto cues. New habits are sparked by external triggers, but associations with internal triggers are what keeps users hooked.

As Yin said, “I just use it whenever I see something cool.” By thoughtfully moving users from external to internal triggers, Instagram designed a persistent routine in people’s lives. A need is triggered in Yin’s mind every time a moment is worth holding on to, and for her, the immediate solution is Instagram. Yin no longer requires an external stimulus to prompt her to use the app—the internal trigger happens on its own.

Building for Triggers

Products that successfully create habits soothe the user’s pain by laying claim to a particular feeling. To do so, product designers must know their user’s internal triggers—that is, the pain they seek to solve. Finding customers’ internal triggers requires learning more about people than what they can tell you in a survey, though. It requires digging deeper to understand how your users feel.

The ultimate goal of a habit-forming product is to solve the user’s pain by creating an association so that the user identifies the company’s product or service as the source of relief.

First, the company must identify the particular frustration or pain point in emotional terms, rather than product features. How do you, as a designer, go about uncovering the source of a user’s pain? The best place to start is to learn the drivers behind successful habit-forming products—not to copy them, but to understand how they solve users’ problems. Doing so will give you practice in diving deeper into the mind of the consumer and alert you to common human needs and desires.

As Evan Williams, cofounder of Blogger and Twitter said, the Internet is “a giant machine designed to give people what they want.”8 Williams continued, “We often think the Internet enables you to do new things . . . But people just want to do the same things they’ve always done.”

These common needs are timeless and universal. Yet talking to users to reveal these wants will likely prove ineffective because they themselves don’t know which emotions motivate them. People just don’t think in these terms. You’ll often find that people’s declared preferences—what they say they want—are far different from their revealed preferences—what they actually do.

As Erika Hall, author of Just Enough Research writes, “When the research focuses on what people actually do (watch cat videos) rather than what they wish they did (produce cinema-quality home movies) it actually expands possibilities.”9 Looking for discrepancies exposes opportunities. Why do people really send text messages? Why do they take photos? What role does watching television or sports play in their lives? Ask yourself what pain these habits solve and what the user might be feeling right before one of these actions.

What would your users want to achieve by using your solution? Where and when will they use it? What emotions influence their use and will trigger them to action?

Jack Dorsey, cofounder of Twitter and Square, shared how his companies answer these important questions: “[If] you want to build a product that is relevant to folks, you need to put yourself in their shoes and you need to write a story from their side. So, we spend a lot of time writing what’s called user narratives.”10

Dorsey goes on to describe how he tries to truly understand his user: “He is in the middle of Chicago and they go to a coffee store . . . This is the experience they’re going to have. It reads like a play. It’s really, really beautiful. If you do that story well, then all of the prioritization, all of the product, all of the design and all the coordination that you need to do with these products just falls out naturally because you can edit the story and everyone can relate to the story from all levels of the organization, engineers to operations to support to designers to the business side of the house.”

Dorsey believes a clear description of users—their desires, emotions, the context with which they use the product—is paramount to building the right solution. In addition to Dorsey’s user narratives, tools like customer development,11 usability studies, and empathy maps12 are examples of methods for learning about potential users.

One method is to try asking the question “Why?” as many times as it takes to get to an emotion. Usually, this will happen by the fifth why. This is a technique adapted from the Toyota Production System, described by Taiichi Ohno as the “5 Whys Method.” Ohno wrote that it was “the basis of Toyota’s scientific approach . . . by repeating ‘why?’ five times, the nature of the problem as well as its solution becomes clear.”13

When it comes to figuring out why people use habit-forming products, internal triggers are the root cause, and “Why?” is a question that can help drill right to the core.

For example, let’s say we’re building a fancy new technology called e-mail for the first time. The target user is a busy middle manager named Julie. We’ve built a detailed narrative of our user, Julie, that helps us answer the following series of whys:

Why #1: Why would Julie want to use e-mail?

Answer: So she can send and receive messages.

Why #2: Why would she want to do that?

Answer: Because she wants to share and receive information quickly.

Why #3: Why does she want to do that?

Answer: To know what’s going on in the lives of her coworkers, friends, and family.

Why #4: Why does she need to know that?

Answer: To know if someone needs her.

Why #5: Why would she care about that?

Answer: She fears being out of the loop.

Now we’ve got something! Fear is a powerful internal trigger and we can design our solution to help calm Julie’s fear. Naturally, we might have come to another conclusion by starting with a different persona, varying the narrative, or coming up with different hypothetical answers along the chain of whys. Only an accurate understanding of our user’s underlying needs can inform the product requirements.

Now that we have an understanding of the user’s pain, we can move on to the next step of testing our product to see if it solves his problem.

Unpacking Instagram’s Triggers

A large component of Instagram’s success—and what brings its millions of users back nearly every day—is the company’s ability to understand its users’ triggers. For people like Yin, Instagram is a harbor for emotions and inspirations, a virtual memoir preserved in pixels.

Yin’s habitual use of the service started with an external trigger—a recommendation from a friend and weeks of repetitious use before she became a regular user.

Every time Yin snaps a picture, she shares it with her friends on Facebook and Twitter. Consider the first time you saw an Instagram photo. Did it catch your attention? Did it make you curious? Did it call you to action?

These photos serve as a relationship external trigger, raising awareness and serving as a cue for others to install and use the app. But Instagram photos shared on Facebook and Twitter were not the only external triggers driving new users. Others learned of the app from the media and bloggers, or through the featured placement Apple granted Instagram in its App Store—all earned external triggers.

Once installed, Instagram benefited from owned external triggers. The app icon on users’ phone screens and push notifications about their friends’ postings served to call them back.

With repeated use, Instagram formed strong associations with internal triggers, and what was once a brief distraction became an intraday routine for many users.

It is the fear of losing a special moment that instigates a pang of stress. This negative emotion is the internal trigger that brings Instagram users back to the app to alleviate this pain by capturing a photo. As users continue to use the service, new internal triggers form.

Yet Instagram is more than a camera replacement; it is a social network. The app helps users dispel boredom by connecting them with others, sharing photos, and swapping lighthearted banter.14

Like many social networking sites, Instagram also alleviates the increasingly recognizable pain point known as fear of missing out, or FOMO. For Instagram, associations with internal triggers provide a foundation to form new habits.

It is now time to understand the mechanics of connecting the user’s problem with your solution by utilizing the next step in the Hook Model. In the next chapter we’ll find out how moving people from triggers to actions is critical in establishing new routines.

REMEMBER & SHARE

- Triggers cue the user to take action and are the first step in the Hook Model.

- Triggers come in two types—external and internal.

- External triggers tell the user what to do next by placing information within the user’s environment.

- Internal triggers tell the user what to do next through associations stored in the user’s memory.

- Negative emotions frequently serve as internal triggers.

- To build a habit-forming product, makers need to understand which user emotions may be tied to internal triggers and know how to leverage external triggers to drive the user to action.

DO THIS NOW

Refer to the answers you came up with in the last “Do This Now” section to complete the following exercises:

- Who is your product’s user?

- What is the user doing right before your intended habit?

- Come up with three internal triggers that could cue your user to action. Refer to the 5 Whys Method described in this chapter.

- Which internal trigger does your user experience most frequently?

- Finish this brief narrative using the most frequent internal trigger and the habit you are designing: “Every time the user (internal trigger), he/she (first action of intended habit).”

- Refer back to the question about what the user is doing right before the first action of the habit. What might be places and times to send an external trigger?

- How can you couple an external trigger as closely as possible to when the user’s internal trigger fires?

- Think of at least three conventional ways to trigger your user with current technology (e-mails, notifications, text messages, etc.). Then stretch yourself to come up with at least three crazy or currently impossible ideas for ways to trigger your user (wearable computers, biometric sensors, carrier pigeons, etc.). You could find that your crazy ideas spur some new approaches that may not be so nutty after all. In a few years new technologies will create all sorts of currently unimaginable triggering opportunities.