3

The Audacity to Succeed

Female doctors are failures! It is a fact there are from six to eight ounces less brain matter in the female, which shows how handicapped she is.

Dr. R. Beverly Cole, Dean, University of California Medical Department

Marie Equi and Bessie Holcomb chose San Francisco—the Queen of the Pacific and the Paris of the West, as it was known—for their new home. In the spring of 1897, Equi was twenty-five years old and more certain of her future course. San Francisco offered three well-regarded medical schools, and she hoped for admittance to at least one of them. Holcomb, at twenty-nine, had proved herself as a teacher and a homesteader. Now she was eager to pursue her interest in landscape painting. After years of living on the land with few career opportunities, the West Coast’s largest city drew the two companions to its storied hills and a new world of promise.

On their way to San Francisco, Equi and Holcomb stopped in Portland where Belle Cooper Rinehart was about to graduate from medical school and return to The Dalles to establish her practice. Then they departed from the recently completed Union Station on Southern Pacific’s California Express for the forty-hour trip to their new home. As the train rolled through the Willamette Valley south of Portland, the two companions viewed the lush farmland claimed by the first homesteaders to the state and then the dense forests that stretched into California. The springtime colors contrasted brightly with the subtle gray-greens and yellow-browns east of the Cascades. The next day, small towns slipped by until they reached the northern extension of San Francisco Bay at Carquinez Strait, where a ferry, long enough to accommodate all the cars, crossed the deep-water channel. A few hours later they reached the Oakland Mole, an immense wooden causeway that jutted into the bay toward San Francisco, giving passengers a direct connection to ferry slips for the final leg of the journey. Late afternoon sunlight streamed from behind the twenty-story skyscrapers in San Francisco, and the slender, graceful clock tower of the Ferry Building, set to open later in the year, beckoned the travelers.1

San Francisco was a great splurge of a city at the end of the nineteenth century, modern and cosmopolitan with a palpable excitement in the air. The city embraced its early Gold Rush reputation—full of extravagant, raucous, and licentious carryings-on—even as it celebrated its status as the undisputed capital of commerce, finance, and the arts of the West Coast and beyond. New arrivals joined the rush of city life as soon as they left the docks and stepped onto Market Street, the main boulevard for business and transport. Cable cars ground to a stop at the Ferry Building ready to collect and disperse passengers down the street or into the neighborhoods. Horse-drawn wagons and handcarts rumbled over the cobblestones, and bicyclists and pedestrians dodged the jumble of traffic as best they could. Runners shouted the best deals at nearby hotels, and newsboys hawked the latest editions.2

San Francisco had fired the public imagination ever since the Gold Rush and few Americans lacked an impression of the city. But the most remarkable aspect of San Francisco at the end of the century was its incredible growth. A mere fifty years earlier a handful of white settlers took refuge from ocean fog and sand-laden winds and hunkered down in cabins at the edge of San Francisco Bay. Until the discovery of gold in 1848 triggered a massive migration to Northern California, the settlers’ outpost failed to register among the one hundred most populous cities in the nation. But when Equi and Holcomb arrived in 1897, San Francisco ranked as the eighth largest in the country. Viewed from prominent hilltops, the spread of the city was striking. More than 340,000 people inhabited houses and apartment buildings that spread over formerly bare sand dunes like an incoming tide that never retreated.3

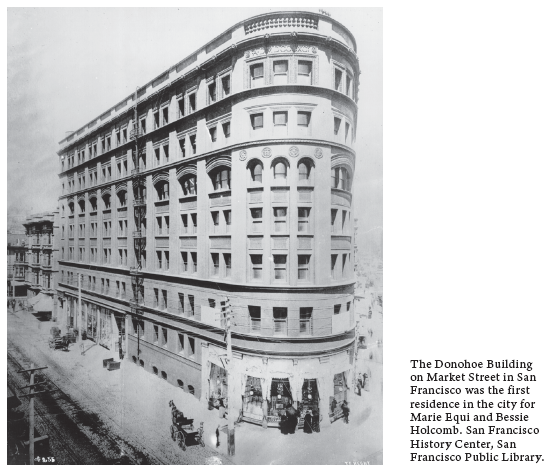

Equi and Holcomb took rooms on Market Street in the seven-story Donohoe Building, one of the better addresses a dozen blocks from the Ferry Building. The department store Weinstock & Lubin filled the street level of the building with all the fashions that never reached The Dalles. The Donohoe sat on one of the triangular blocks created by Market Street’s diagonal slash through two different street grids, and in the middle of the triangular block spread the Bay City Market, crammed with fruit and vegetable stalls, a sausage factory, and specialty vendors. Two blocks farther west on Market Street stood City Hall, completed after only twenty-seven years of construction. Its ungainly, slender dome was easily outclassed by the elegant Hall of Records nearby. A block south of Market on Seventh Street, Italian craftsmen labored on the federal courthouse that would figure prominently in Equi’s future.4

Within this big-city tumult, Equi needed to find a job. To pay her rent and save for tuition, she took a cashier position at Miss Tillie Taylor’s restaurant, a small operation on Post Street not far from San Francisco’s Union Square. The elite Olympic Club and a synagogue faced Miss Taylor’s restaurant, and the new City of Paris department store nearby was the talk of the town. With her new job, she joined the 20 percent of American women at the time who delayed marriage—or avoided it altogether—and entered the workforce. Holcomb relied on her savings, or assistance from her parents, and undertook painting rather than becoming one of the city’s well-paid teachers. Her work attracted attention in local art circles, and she exhibited at the Mark Hopkins Institute and at the Mechanics Institute Fair. Years later, in 1905, Holcomb was included in a newspaper write-up titled “New Names in Art that Show Promise.” Both newcomers typified the emerging New Woman who stepped away from traditional roles and economic restraints, but Equi’s aspirations to become a doctor bucked the norms even among working women. Only 6 percent of all physicians in the country were female.5

Marie Equi was not the first in her family to settle in San Francisco. Her father’s younger brother Joseph had left New Bedford when news of the Gold Rush still tantalized easterners. He settled first in Sonoma in Northern California and prospered with a produce business during the 1870s, and then relocated his family and business to San Francisco’s Mission District. Equi’s aunt Fortuna, her husband, Paolino Galli, and their four children also made a home in the city several blocks west of City Hall, where they managed a fruit and vegetable stand. Equi’s move to San Francisco may have occasioned her first meeting with her California relatives, but her reputation had preceded her. Four years earlier, the widely read San Francisco Examiner carried an account of her horsewhipping a Baptist minister in a small Oregon town.6

Equi and Holcomb found that many more single women roomed together in San Francisco for the sake of economy and companionship, and their arrangement was unlikely to prompt much comment. (Their bond held firm, and in March 1898 Holcomb honored Equi’s help proving the homestead claim by deeding her a half share of the property.)7 But overall little is known about San Francisco’s social environment for women seeking intimate company with other women during the late 1890s. Equi’s outgoing nature may have eased the entry for them into a new social circle, and Holcomb, too, would have probably befriended women, lesbians among them, interested in art. The public’s understanding of homosexuality in the late nineteenth century was limited for the most part to newspaper reports of sensational affairs. Accounts of same-sex activity during the city’s early decades relate mostly to Gold Rush–era men cavorting together in campfire dances and skits. Occasional stories of men and women passing as the opposite sex suggest that variations in sexual behavior were introduced early into San Francisco’s culture. In later decades, the men who caroused in the city’s no-holds-barred dives on Pacific Avenue contributed to the city’s reputation as Sodom by the Sea.8

The appearance of Oscar Wilde in San Francisco in 1882 had sparked great interest and titillation for more mainstream society. Wilde was a twenty-eight-year-old Irish aesthete from London, a celebrity known for his refined tastes, effeminate garb, and theatrical prowess. When he lectured on art and decoration, he did so dressed in his signature velvet coat, lace cuffs, short breeches, and long stockings. At his other American stops, Wilde’s audience reportedly included “pallid young men with banged hair.” For many Americans, Wilde’s tour and the newspaper coverage of it was their first, substantial exposure to homosexuals, and it shaped their opinions of alternative, outsider sexuality. Then, in 1895, the American public had vilified Wilde as a degenerate reprobate after he was convicted and sentenced to prison for having sex with a younger aristocratic man. The incident forced Americans to recognize that same-sex activity extended beyond the lower classes, although they could dismiss it still as a proclivity of distant European elites.9

Most applicants to medical school gained entry by presenting a high school or college diploma, a teacher’s certificate, or proof of prior acceptance from another college. But for individuals like Equi who never completed high school, the successful completion of an entry exam was the only option. Passing an English exam had been the sole requirement in years past, but criteria steadily became stiffer. A few years after Equi’s application, San Francisco’s medical schools removed the entry exam as an option and required a minimum of a high school education. A few required two years of college as well.10

The increasing demands on applicants reflected a major, long-term transformation of American medical education toward more professionalism. A great many doctors, represented by the American Medical Association (AMA), wanted to bolster the public’s regard for their profession by increasing competency among practitioners. They hoped their support for stricter entry requirements would block unqualified applicants and, not coincidentally, reduce competition and increase their own incomes. In time many of the private medical colleges became affiliated with universities and adopted those institutions’ higher standards for admission and training.11

In the midst of these fluctuations, Equi’s plans for medical school were well timed. She gained entry when requisites were within her reach, and she began coursework when the quality of instruction was steadily improving. Her trajectory was remarkable. Ten years after dropping out of high school at age seventeen, she was on her way to becoming a professional. Equi’s determination and audacity transcended the limits of her working-class roots and carried her to the steps of a medical college.

Just fifty years earlier in 1849, Elizabeth Blackwell became the first woman to graduate from an American medical school. Her achievement marked the start of women’s arduous and protracted struggle to enter a profession other than teaching. Initially female applicants were so regularly refused entry to medical colleges that they resorted to institutions founded for women alone. Once state universities started to admit women to their medical departments in the 1870s, however, the number of their female students soared. By 1880 women graduates in medical practice increased tenfold to nearly 2,500. By the time of Equi’s first year of study, nearly 7,400 women practiced medicine nationwide. Ironically, she began her studies when women were at the peak of enrollment. Within a few more years, their numbers began a long-term decline caused by the closing of women’s schools, increasing costs of education, more demanding entrance requirements, and ongoing gender discrimination.12

In October of 1899, Equi enrolled at the College of Physicians and Surgeons, one of San Francisco’s three schools of regular medicine, meaning allopathic and not alternative. Founded in 1896, “P&S,” as it was widely known, was San Francisco’s newest medical college. A local dentist and entrepreneur had founded the school and made it a successful venture, partly by charging each faculty member $500 for a full professorship. For their part, first-year students paid at least $115 for matriculation, tuition, and anatomy lectures. The fees were too steep for Equi, and Holcomb helped her with tuition.13

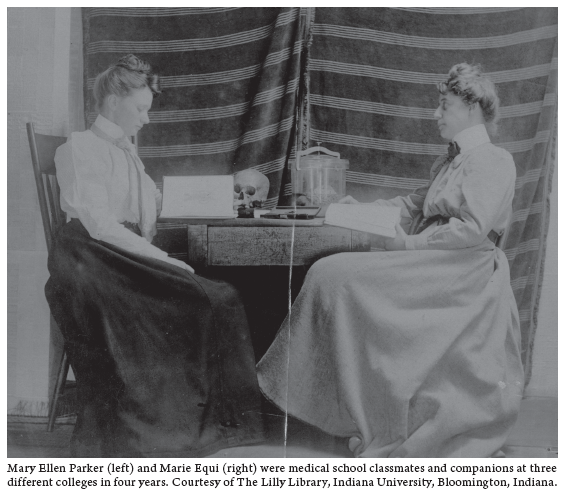

The three-story P&S building featured well-furnished lecture rooms, specialty laboratories, and dissecting rooms. Located at Fourteenth and Valencia Streets in the Mission District, the college boasted a convenient location opposite the Southern Pacific Hospital and near the City and County Hospital, prized for the clinical experience it offered students. P&S was coeducational at its founding, and two to three women were registered in each year’s freshman class. In the mostly male environment, women students found allies where they could, and Marie Equi was fortunate to befriend Mary Ellen Parker, a younger woman who had spent much of her life in the eastern Sierra town of Bridgeport, California. Her father was a Scottish immigrant and a successful attorney, and her mother was a homemaker and a devout Roman Catholic of Irish descent. Parker earned a teaching certificate in Ogden, Utah, before starting her medical studies in San Francisco. She was more reserved than Equi but, according to her relatives, she was every bit as intelligent, opinionated, and strong willed. In their first year Equi and Parker studied the full range of sciences in addition to pharmacology and physiology. Their instructors were all men since the few women professors at P&S taught courses not open to first-year students—gynecology, abdominal surgery, and medicine. But Equi became acquainted with a few of the women faculty and impressed them enough to be invited to intern with them in the years ahead.14

With the end of the fall term, students might have engaged in the national debate raging over America’s military conduct after its victory in the Spanish American War of 1898. The US had injected itself into the colonial insurrections of Cuba and The Philippines against Spain, the old colonial power of the Americas, and the nation’s leaders positioned San Francisco as the lead city for a new American empire. Business titans were all too willing to cooperate. They envisioned San Francisco dominating Pacific Basin trade much as it already did on the West Coast.15

The American public rallied to the independence movements, yet intense economic and geopolitical interests powered the country’s involvement in further hostilities. After the end of the war with Spain, the US triggered another conflict with Filipino insurgents who refused to trade the yoke of colonial Spain for the shackles of industrial America. The betrayal of the freedom-seeking Filipinos and the increasing American war casualties troubled the public back home. Soldiers’ letters about sweeping through whole villages and leaving no one alive stoked public doubts even more. The Anti-Imperialist League, with thirty thousand members nationwide, railed against the war and the new spirit of militarism. The league was no ragtag group of dissidents—its supporters included Mark Twain, Samuel Gompers of the American Federation of Labor, the industrialist Andrew Carnegie, and social activist Jane Addams. Even former presidents William Henry Harrison and Grover Cleveland signed up as members. But the anti-imperialists were overwhelmed by rampant yellow journalism that stirred war fever and the prospect of windfall profits for American businesses.

We can only speculate whether Equi shared the antiwar activity and distrust of America’s industrial claims for the end-of-century wars, but the sentiments extended into the twentieth century and later commanded her full attention.16

In early 1900 Equi and Holcomb reduced their expenses and relocated to a large apartment building on Franklin Street near City Hall. They rented rooms from a young German-American telegraph operator and his wife, and Mary Ellen Parker took an apartment one block away. Saint Ignatius College and Church dominated their new neighborhood, filling one complete block, and attracting visitors with the majestic sound from the 5,300 pipes of its new organ.17

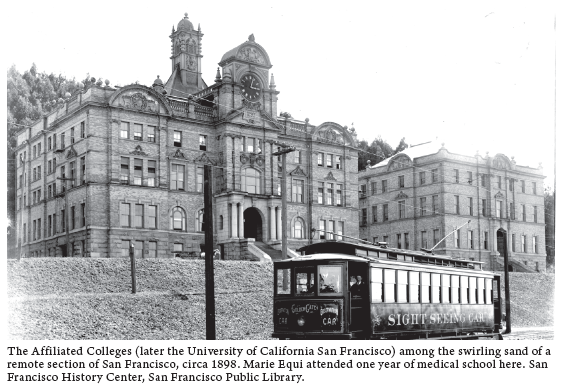

Equi and Parker completed their first year of study at P&S, and then in the autumn of 1900 they transferred to the new campus of the University of California Medical Department, located on a distant, fog-swept hill overlooking Golden Gate Park. The medical department had begun as Toland Medical College, one of the city’s first proprietary schools. Like other private medical schools in the West, Toland was established by a strong-willed man of medicine, Dr. Hugh Toland, who positioned his investment for every advantage. After several years of prospering, however, the college floundered amid faculty rivalries. In 1873 Toland offered the operation to the regents of the state university, and Toland Medical became a professional school of the University of California in 1873. As a result of the merger, the new department adopted the university’s open admission policy for women, making it the first coeducational medical school in the state.18

Yet women students found little welcome at the university’s medical school. In the 1890s, Helen M. Doyle recounted that both professors and male students treated women students as “an experiment and something of a joke.” The professor of obstetrics and gynecology liked to disparage women as having “six to eight ounces less brain power” than men. When Doyle graduated, a female classmate received the highest marks of any graduate in the previous ten years.19

Equi’s new campus with three main buildings offered few amenities, and it was linked to the city by a single trolley line. But Equi and Parker began once again to fit into a new academic community. Their sophomore year was a time to study the scientific basis of medicine before delving into aspects of clinical care, and course work included anatomy with a focus on dissection, organic chemistry, and an introduction to embryology. In the year 1900, students also observed the real-life interplay of medicine, public health, and politics when an outbreak of bubonic plague took hold in San Francisco. City and state leaders disputed and discredited the reports of plague—all in the interest of protecting commerce and civic reputation—until the prevalence of the scourge became too obvious to hide.20

Something went awry for Equi during her second year of study. Under ideal circumstances, sophomores immersed themselves in the academic culture of the institution and forged bonds with peers and professors, who would be their colleagues after graduation. But Equi completed the semesters only to transfer yet again to a third school. This time she chose to leave San Francisco and the state altogether for reasons that were perhaps more personal than academic. She could obtain no better medical training in the West than what was available in San Francisco, and another transfer required establishing herself with new professors and a new student body. That may have been the point. Given the harassment of women students and Equi’s quick temper, her relations at the school may have soured, but her changed relationship with Bessie Holcomb may have been a factor as well.

Holcomb’s steady presence in Equi’s life from New Bedford to San Francisco had given her a secure base as she set her career path and matured as a woman. They had enjoyed the flush of intimacy that defined their homestead years and the sense of adventure from settling into San Francisco, but, in 1901, after nearly ten years of companionship, their interests diverged. Equi had drawn close to Parker, and Holcomb had begun a new relationship as well—this time with a man. She had taken a job as a stenographer for the Wagner Leather Company, an outfit in the Financial District that sold shoe leathers, skirtings, and harnesses. There she started dating her boss, the firm’s senior manager, Alexander J. Cook. Holcomb was in her early thirties, and she was apparently drawn to a more conventional life with a husband and children. Within three years she and Cook married and made their home in San Francisco.21

As Equi prepared to leave the Bay Area in 1901, tinderbox politics threatened the nation. On September 6, Leon Czolgosz, a factory worker and a son of Polish immigrants, shot and gravely wounded President William McKinley at the world’s fair in Buffalo, New York. Once police apprehended Czolgosz, he proclaimed his adherence to the radical views of anarchist Emma Goldman, whom he had heard speak in Chicago four days earlier. Police arrested Goldman and charged her with inciting the attempted assassination, even though she had met Czolgosz just once and briefly. The “guilt-by-lecture” accusation did not hold, and Goldman was eventually released. But the antipathy toward anarchists in the country became more intense and pervasive after the president died of his wounds. Czolgosz was eventually tried, convicted of murder in the first degree, and executed by electrocution. Theodore Roosevelt assumed the presidency, and the fevered antagonism toward radical activists ebbed, at least for a while.22

Equi is not known to have engaged in politics during her San Francisco years. Woman suffrage might have commanded her attention, but California’s right-to-vote campaign slumped after a stinging defeat in 1896 and had yet to rebound. As Equi took her leave of California, San Francisco remained a touchstone, the place where she had persevered and set her course toward a life as an independent professional woman.