4

Doctor and Suffragist

Marie D. Equi: A Fearless Champion of Freedom for Women

Abigail Scott Duniway, Oregon’s woman suffrage pioneer

This time Marie Equi chose Portland—the cool, green metropolis of the Pacific Northwest. She arrived in 1901 at the cusp of Portland’s boom times. An influx of twenty-five thousand newcomers boosted the population to ninety thousand over a three-year period. In another ten years, the number would double and make the city one of the fastest growing in the nation. Civic leaders envisioned a regional powerhouse and a commercial gateway to Pacific nations. At a time of high civic spirits, Equi passed through Union Station with a new companion, Mary Ellen Parker, and a letter of admittance to her third medical school.1

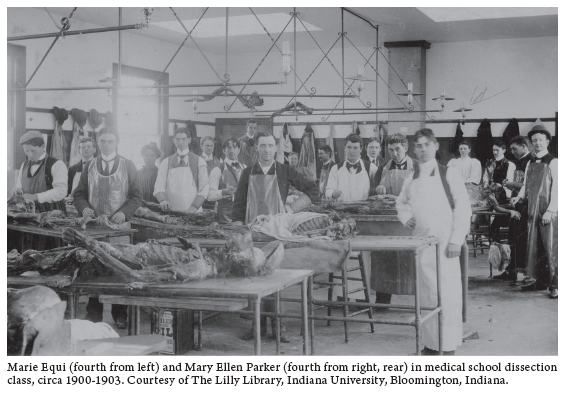

Portland offered the only study of regular medicine north of San Francisco. In 1867, Willamette University organized the first lectures in medicine in Oregon, and the university provided the state’s sole medical education for twenty years. But, in an example of the intensely bitter academic rivalries that bedeviled medical colleges at the time, four defiant professors bolted the department ten years later and established a rival in 1887: the University of Oregon Medical Department. Equi chose this new school to complete her studies. She and Parker enrolled in September 1901 and joined ninety other students in a three-story building with soaring gables and peaks on the outskirts of the downtown district. In their class of ten students, Equi and Parker were two of five women, an unusual male and female equity for a medical school. Yet the university had welcomed women since its founding, and, in 1901, the fourteen female students in all the departments represented 15 percent of the student body.2

The third year of medical school marked a shift toward the actual practice of medicine, and, in Portland, students undertook clinical work at Good Samaritan Hospital, located across the street from the school. Equi wasn’t known to fault her new school, but the medical department fared poorly in what became known as the Flexner Report, an evaluation facilitated by the American Medical Association. Given its scant resources, limited library holdings, and lack of full-time professors, the reviewers concluded the department lacked a credible reason to exist. As might be imagined, university faculty and administrators took exception to the findings and sparred with the AMA for several years.3

Despite their greater numbers, female medical students in Oregon suffered hostility from male faculty and students. At Willamette University, Mary B. Purvine complained in her memoirs of “a terrible existence” as the only woman in a class of four men who made her the butt of their vulgar and abusive jokes. In other schools the harassment discouraged many women from completing their studies or from entering the profession after they graduated. However, a number of women managed to negotiate their student years with less confrontation. Esther Pohl Lovejoy described a more harmonious time with the mostly male student body at the University of Oregon when she attended in the early 1890s. But she was also dating one of the male students at the time and that association probably shielded her. Equi, on the other hand, was a single woman associated with another woman, and both her assertiveness and her sexuality probably factored into the treatment she received. She later confided that the harrassment often led her to throw herself on her bed by the end of the day.4

Equi and Parker had become close companions, and they shared an apartment a few blocks from the university. At one point, they sat for a portrait photograph together, facing each other with a human skull and stacks of books artfully placed on a table between them. Equi struck a reflective, confident pose while Parker appeared tentative and self-conscious. But they developed a good rapport and forged a bond that lasted for years. Equi later joked that during their school years in Portland they would dissect cadavers in the morning and then toss back drinks in the afternoon to get a free lunch. When away from her studies, Equi worked part-time as a nurse to pay her tuition, and, in the summer, she provided medical care for a company in the gold mining region outside Bridgeport, California, Parker’s hometown.5

In their studies and reading, Equi and Parker were probably exposed to the increasingly popular theories of European psychologists regarding sexual identities and behaviors, including homosexuality. How they described or identified their own same-sex relationship is not known. But they continued to room together in an arrangement that saved on rent, provided mutual support, and, possibly, led to romance and sex.

Just as Equi completed her four years of study, a respected Oregon physician tried to block her graduation. Dr. Belle Cooper Rinehart pleaded with the dean of the medical school, Dr. Simeon E. Josephi, to withhold a diploma from Equi, saying she was unfit to practice medicine. Rinehart was the same woman whom Equi had befriended following the horsewhipping incident ten years earlier in The Dalles. Yet in 1903 Rinehart made a special trip from The Dalles to derail Equi’s career. According to reports filed years later, she told the dean that Equi had a violent temper and had once threatened her companion, Bessie Holcomb, during an argument. Whether Rinehart was also motivated by issues in her own relationship with Equi is not known. The dean was well aware of Equi’s temper as faculty members had complained that she used “very bad language” over the telephone. Equi’s short fuse became well known in later years, and there’s little doubt that it flared earlier as well. But Rinehart’s complaint failed to persuade the dean, who might have found it odd that with the very low percentage of women doctors one would turn against another to such an extent. He knew Equi had completed her coursework satisfactorily. He was certainly aware of disagreeable traits among other established physicians, and, perhaps, he was reminded of his own strong-willed, contentious past when he abandoned the faculty of Willamette University to establish the department he now led.6

As it happened, Equi’s particular mix of anger and sense of justice landed her in the Oregonian a few weeks before her graduation. The paper reported an incident in which Equi slapped a male student after he belittled her as a “fool.” During a classroom dispute over a proposed student fee to support campus football—a sport open only to men at the time—she objected to the discriminatory nature of the payment. Seventy years before the federal law known as Title IX guaranteed equity in athletics for women, Equi argued that women received no direct benefit from the fee yet they would be required to pay dues in order to vote in student body elections. Equi never took kindly to insult or mistreatment, no matter the stature of the offender. She explained to the newspaper that she also objected to the preferential treatment given male students in all facets of student life.7

Sixteen years after dropping out of high school to work in a textile mill, Equi gathered with other seniors for graduation ceremonies held at Portland High School. They settled into the assembly hall filled with friends and family while a string orchestra played Tchaikovsky’s Chant sans paroles. In his address to the graduates, Dr. K. A. J. Mackenzie encouraged the students to undertake postgraduate work at hospitals on the East Coast or in Europe, if possible, and then to settle in a well-to-do rural district before trying to establish themselves in the city. He earned a round of applause for his final advice: “Don’t settle in a place that is too healthy.”8

Equi’s journey from a factory job in Massachusetts to a profession in Oregon demanded fortitude and resilience, and her achievement was all the greater given her background. In 1900 only 17 percent of all women physicians were native-born children of one or more immigrant parents. In Oregon she was among the first sixty women to graduate from a state medical school. Yet an additional hurdle remained—a medical license. Before 1895 anyone with a medical school degree could easily obtain a license to practice medicine in Oregon. By 1903, however, the state board of medical examiners required a written test of all new graduates and of any physician recently moved to the state. On April 9, 1903, Marie Equi and Mary Ellen Parker passed the examination and received their licenses, joining the ranks of the first professional women practicing in the Pacific Northwest.9

New doctors did not necessarily feel prepared for patient care as soon as the ink dried on their licenses, and by 1904 about 50 percent of them in the United States undertook hospital internships for advanced and supervised training. Those who could not obtain or afford positions on the East Coast or in Europe sought openings at local hospitals, and a few relied on preceptorships with experienced physicians in private practice. In Portland, however, women graduates found few opportunities for either kind of work.10

Equi and Parker secured their internships in San Francisco instead. Equi worked for six months with Dr. Florence Nightingale Ward, a respected surgeon and national leader in homeopathic medicine. Ward had graduated from San Francisco’s Hahnemann Medical College of the Pacific, the center of homeopathic education in the West, before taking advanced study in gynecological surgery at hospitals in New York and in Europe. She returned to San Francisco and established what was later described as the largest practice of a woman physician west of Chicago. As an apprentice to Ward, Equi became familiar with the most advanced surgical procedures. She also learned to provide care in the homeopathic tradition of extensive physician-patient communication, limited invasive procedures, and use of small doses of substances to prompt the body’s normal healing processes. On a collegial level, Equi observed in Ward an independent, determined woman who achieved considerable success without compromising her principles.11

Equi was fortunate to seek her homeopathic training at a time when the gap between regular medicine and homeopathy had narrowed, the open war from 1850 to 1880 between the two disciplines having subsided. By supplementing her training with homeopathic practices, Equi enhanced her competitive advantage in the medical marketplace on the West Coast. In Portland, as well as in San Francisco, medical practitioners included physicians licensed in regular medicine, and others who based their services in homeopathy, physio-medical treatments, Chinese medicine, and midwifery. Entrepreneurs who offered patent medicines and supplements rounded out the competition.12

Over the next few years, Equi returned to San Francisco for ongoing advanced study, and worked with Dr. Sophie B. Kobicke, one of the few specialists in the city who understood the new and complicated procedures associated with bladder and kidney surgery. During her stints in the city, Equi kept a rigorous schedule with shifts three days a week at the public hospital clinic on Mission Street and another three days at Cooper Medical College where she assisted gynecologist George B. Summers with operations.13

With a mix of courage and pragmatism, Equi and Parker left San Francisco in November 1903 to establish practices in Pendleton, Oregon, a town of six thousand people, situated 230 miles east of Portland in the northeastern section of the state. They apparently took heed of Dr. Mackenzie’s advice at their graduation ceremony to start working in a rural district to learn how to manage a practice.

Pendleton stretched along the south bank of the Umatilla River as it rushed westward through rolling hills of sagebrush and grasses from its headwaters in the snow-capped Blue Mountains. With the coming of the railroads in the early 1880s, Pendleton boomed as a commercial hub for the farmers and ranchers of the region. By rail and river, Eastern Oregon’s wheat, livestock, wool, and fruit were carried to the markets in Portland and beyond. The trade helped establish Pendleton as the fourth largest city in the state by the early 1900s. Residents boasted of running water, electricity, telephone service, and paved roads. They took pride in its opera house, its business college, the downtown Italianate commercial brick buildings, and the Queen Anne houses in the southside neighborhoods. But the city was hardly a benign outpost. With more than thirty saloons and at least a dozen brothels, Pendleton was the good-times favorite among the region’s cowboys, ranch hands, and out-of-towners.14

Physicians were always in short supply in Central and Eastern Oregon, and Pendleton touted two draws for prospective practitioners: the Sisters of St. Francis opened St. Anthony’s Hospital in 1903 and the federal government hired doctors to provide medical care to the Cayuse, Umatilla, and Walla Walla peoples at the nearby Umatilla Indian Reservation.15

Equi and Parker registered with Umatilla County authorities on November 2, 1903, and established their office as well as their lodging in the ornate stone and brick Judd Building downtown. They joined eleven established doctors, all men, with offices in town.16

Physicians working in Oregon’s high desert and plains dealt with challenges far different from those found in cities. They often traveled for hours by horseback or buggy to reach patients at distant ranches and homesteads. Once they arrived, the doctors frequently found that prospective patients mistrusted what they considered New Medicine, preferring their own folk remedies instead. Fred deWolfe, a local chronicler who became a statewide journalist, later wrote of Equi’s unstinted courage and dedication on the range. According to his account, Equi rode on horseback in the countryside providing medical care to Indians and cowboys.

Medical care for the local tribes was a complicated affair, and the degree to which Equi actually provided treatment is uncertain. By the early 1900s the Indian population had been decimated by diseases of the white men, and their own doctors were unable to cure many of the new maladies, resulting in a loss of tribal status for them. Indians on the reservation often had little choice but to accept medical care from white doctors, though it could be equally ineffective. Equi was not among the contract doctors serving the reservation, and native peoples living off the reservation were unlikely to summon her for medical care. But circumstances were fluid, and she may have assisted them on occasion. In any event, the accounts of Equi’s doctoring in the remote stretches of Umatilla County burnished her reputation.17

Equi’s general practice thrived, and she later recalled that she had all the work she could handle. Ten years earlier a local paper, the Pendleton Tribune, had covered the story of the young woman who horsewhipped a Baptist minister in The Dalles, but if people in town connected the story to Equi, no accounts appeared of undue interest about the two new women doctors setting up practice and living together.18

Unlike Equi, Parker found little success in Pendleton with her own practice, and she attracted few patients seeking treatment for her eye, ear, nose, and throat specialty. After several months of effort, she decided to seek opportunity elsewhere. Equi chose loyalty to her companion over her own more promising start, and she and Parker returned to Portland.19

Equi appeared to relocate with relative ease, but her moves also reflected the demands on women practitioners at the time. Like most female doctors, she sought the best choices among the few possibilities. In Portland she and Parker took a fifth-floor office in the nine-storied Oregonian Building, the city’s first skyscraper, located at Sixth and Alder Streets in the core of the downtown district. Erected in 1892 in the grand Richardson-Romanesque style with a sculpted stone exterior, the building featured a 203-foot clock tower that served as a civic timepiece. The building offered all the modern conveniences—electricity, artesian water, and elevators—making it the most popular commercial address in the city. The two women shared an office large enough to accommodate a waiting room and two examining areas outfitted with the typical equipment of the day: a table or reclining chair for the patient, a cabinet for pharmaceuticals, brass scales, and the means to sterilize instruments. They posted their examining room hours—ten to noon in the morning and two to five in the afternoon with evening hours reserved for visiting patients in their homes. And, once again, Equi and Parker rented an apartment together, this time on Jefferson Street, several blocks from the city’s center. Overall business was booming in Portland, and apparently the two new doctors prospered enough to afford their new surroundings. They settled into familiar city rhythms—the horse-drawn sprinklers that dampened dust on downtown streets, the Southern Pacific locomotives still steaming along Fourth Street—with every reason to expect a bright future.20

Women doctors remained a novelty, even in a state like Oregon that licensed nearly twice the national percentage of female practitioners. The greater numbers in the state probably reflected the early acceptance of female students in the medical schools. A niche for women existed in Portland’s medical world, but many people thought the mix of new medicine with its emphasis on precise causes for specific diseases and the New Woman ready to treat their maladies was too much too soon. Most women physicians in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries specialized in treating women and children. Like Equi, many had witnessed the difficulties of childbirth and the scourge of childhood diseases in their own families. They welcomed the opportunity to improve women’s conditions and provide sound care to children, but other women resented the constraint on their professional aims. Male doctors, after all, felt no compunction to establish practices mostly for male clients. But women doctors were a hardy bunch by and large, and many accepted what was available even as they pushed against the barriers. Obstetrics posed a different problem. New women doctors seeking to specialize in obstetrics tried to sidestep lingering resentments over physicians who wanted to usurp the traditional role of midwives. They avoided any suggestion that they were better trained than midwives, and one doctor negotiated this uncertain terrain by making her reputation in surgery so that she could “enter obstetrics through a surgical door . . . with skill and distinction.”21

Equi readily established her general medicine practice in Portland in 1905 with an emphasis on obstetrics and gynecology as well as maternal and childhood health. The internship in San Francisco had helped her develop a reputation as a skilled diagnostician, and her background in New Bedford gave her a natural rapport with Portland’s working-class and immigrant populations. In the year Equi started seeing patients, nearly eight hundred people died of tuberculosis in the state. Typhoid fever claimed a death rate of 25 percent, and measles scored the greatest prevalence with more than eight hundred cases reported in Portland alone. Children all too often contracted diphtheria, the same malady that claimed Equi’s younger brother during her childhood. No effective remedy was available then, but Equi and her colleagues relied on an antitoxin for treatment.22

Equi’s expertise encompassed more than the infectious diseases of the day. In February 1905 she lectured on “Nervousness in Children” before Portland’s Home Training Association, and an account of her talk was published in the Oregonian. She described the common symptoms of nervousness and then linked the condition to a combination of heredity and environment. She emphasized that such children were “painfully aware of faults,” and she advised caretakers to avoid harsh criticism, to help the child learn self-control, and to guide the use of nervous energy. Her prescriptions seemed to draw on her own experience as a schoolgirl in New Bedford, and they suggest an interpretation of her own early behavior.23

Once established with an office and home, Equi and Parker renewed their involvement with the Portland and Multnomah County Medical Society and the Oregon Medical Society. Although the state organization first accepted women in 1877, the local society excluded women until 1902, a full eighteen years after its founding. Two years later Equi and Parker were also admitted, and women doctors then totaled more than a dozen. Women welcomed the recognition from the medical associations, but they also formed their own alliance, the Medical Club of Portland, in 1900 to support each other more directly. Among the members, Equi formed several close relationships that continued for decades.24

Portland’s ongoing commercial and residential growth was only one of the big stories in Oregon when Equi began her medical practice in the city. Beginning in 1902, the state’s male electorate approved so many “direct democracy” reforms that pundits and reformers across the nation hailed the Oregon System as a harbinger of civic and political transformation. Before the enactment of the sweeping changes, citizens had no direct means to place measures on the ballot, repeal laws, recall elected officials, or elect their US senators directly. Most importantly, women lacked the fundamental facet of citizenship: the right to vote.25

Oregon’s innovations reflected a new force in the nation’s body politic—a political vision and undertaking called Progressivism—that expressed a yearning for social change and a widespread discontent with the intrusions of corporate interests into American politics. Progressives hoped to forge a new political paradigm free of domination by corporate power brokers and guided by a robust exercise of citizen engagement. In this movement Marie Equi found her initial footing as an activist.

Progressives lobbied the federal government and local municipalities to adopt policies and undertake programs to improve society and protect the public. They pushed for a more enlightened social order that shielded women and children from abuses on the job, expanded voting rights, and regulated consumer goods. And they urged reforms in the civil service system to steer control away from political hacks. During the first two decades of the new century, Progressives’ efforts steadily loosened the grip of the industrial and corporate elite over the workforce and of the political party bosses over the political process. But the reform-minded advocates also embraced measures of social control that proved to be intrusive and problematic.26

Women ready for social and political change were especially drawn to the Progressive agenda, and at first they focused on public health measures and protection of those most vulnerable to injustice and unhealthy environments. They supported civic housekeeping, a broad array of initiatives to sweep corruption from local government and help single women, unwed mothers, and families struggling with unemployment and poor health. Once they engaged in essentially political activism, women became increasingly convinced their success in the civic realm depended on securing the right to vote.27

Equi started her career in Portland during the early, frothy days of the Progressive and feminist fervor in the city. She was familiar with political strife—from workers’ strikes in New Bedford and protests by the unemployed in The Dalles to longshoreman shutting down San Francisco’s waterfront. But not until she secured her own livelihood was she known to engage in struggles for civic reform and economic justice.

The work of Oregon’s relentless and indomitable woman suffrage leader, Abigail Scott Duniway, drew Equi to the push for the right to vote. She was nearly forty years younger than “Mrs. Duniway,” as everyone referred to her, and their life experiences were vastly different. But Equi found in the older woman an accomplished, self-made advocate with a fiery temperament and a big-hearted embrace of life. For the first time perhaps, she was in close association with a woman whose traits and passion mirrored her own. Duniway came to appreciate Equi’s commitment as well and later wrote of her, “Marie D. Equi, a fearless champion of freedom for women.”28

For more than thirty years, Duniway had carried the suffrage message across Oregon, and no road was too rutted or muddied, no public gathering too small or hostile to disrupt her mission. She was as comfortable with businessmen, attorneys, and doctors as she was with farmers, ranch hands, and housewives, and she marshaled her own considerable experiences to engage audiences with a mix of feminist advocacy, frontier lore, and strident barbs at opponents. Her rough-hewn manner, defensiveness, and stubbornness often alienated other suffragists and weakened her campaigns, but she believed she knew best and her critics found her perseverance difficult to ignore. Those who knew her well understood the influence of her background on her personal and political behavior.29

Abigail Jane “Jenny” Scott, the future Mrs. Duniway, was an often sickly girl of seventeen when her father uprooted the family from their Illinois farm in 1852 for a glimmering hope of something better in the West. Jenny had spent five months in “an apology for an academy” in which she “never did, could or would study.” She distrusted authority, resisted discipline other than her own, and resented the farm work expected of her. For the trip West, Jenny’s father appointed her chronicler of their trek, a task she initially resisted. Later she used her frontier experiences to pen Oregon’s first commercially published novel, Captain Gray’s Company, in 1859. In Oregon, Jenny married Benjamin Duniway and became a farm wife with six children. When an injury permanently disabled her husband, she alone supported the family by both teaching and opening a millinery shop. The business venture exposed her to dozens of women burdened by a legal system that favored men and left wives responsible for their husband’s debts. Their plight convinced her that women needed the vote to exercise their citizenship but especially to wield the power necessary to change their circumstances.30

In 1870 Duniway organized Oregon’s first state suffrage association. The following year she persuaded Susan B. Anthony, the national suffrage leader, to join her on a campaign tour throughout the state, creating a bond between the two leaders that lasted three decades before unraveling. Starting in 1872, Duniway led one attempt after another to wrest the right to vote from Oregon’s male electorate. She rallied Oregon’s suffragists for one more try in 1906.31

Equi joined the Oregon Equal Suffrage Association, the organization led by Duniway, to secure the vote. She learned at the start that Duniway insisted on a “still hunt” strategy, a low-key effort with no rallies and little public organizing. The longtime leader believed in recruiting influential men and women to the suffrage cause without stirring the passions of the general electorate or the known opponents. Her methods riled the directors of the National American Women Suffrage Association (NAWSA), the country’s primary right-to-vote organization. They preferred a “hurrah campaign” filled with public lectures, canvassing, endorsements, and parades. Susan B. Anthony, the venerated president of NAWSA, had concluded years earlier that Oregon would never close the deal on suffrage with Duniway in command. Circumstances had changed for the one-time friends once NAWSA leaders sought to exert their influence in state campaigns. Duniway’s insistence on a more subtle approach no longer meshed with what Anthony had in mind, and the resulting struggles between state and national leaders injected fractious, often bitter, infighting into local efforts. The conflicts were to be expected as strong, driven leaders were needed for the massive undertaking of changing laws in all the states. And, more to the point, no particular campaign strategy had proven successful across the board, leaving battles over strategy inevitable.32

In 1905, circumstances favored NAWSA’s campaign strategy when Portland hosted the first world’s fair in the Pacific Northwest. These grand events were still all the rage in the country after earlier extravaganzas in Chicago, Buffalo, and St. Louis. Americans flocked to see industrial and scientific marvels, towers of elaborately arranged agricultural goods, and the best fine arts the host city could muster. Portland’s event, the Lewis and Clark Exposition, marked the centennial of the American exploration of the Oregon Country, and it positioned the city as a destination for settlers and a prime prospect for investors.33

The fair drew exhibits from twenty-one nations and most of the states to the Guilds Lake area on the outer-reaches of northwest Portland. Each built its own pavilion on the fairgrounds, and Oregon erected an imposing Forestry Building with enormous fir tree trunks still clad with bark. It was quickly dubbed “the biggest log cabin in the world.” The exposition was wildly successful and drew more than one and a half million visitors who were thrilled to see the first automobile built in Oregon, Infant Incubators where six babies were nurtured to gain strength, and the motor-driven blimp piloted by eighteen-year-old Lincoln Beachey in the first lighter-than-air flight in the Pacific Northwest.34

Portland’s physicians rallied to welcome fairgoers. Equi, Esther Pohl, and other doctors served on the bureau of information committee to greet visiting doctors, and the medical society helped host the annual meeting of the American Medical Association. But most of Equi’s attention focused on the first NAWSA convention to be held in the West.35

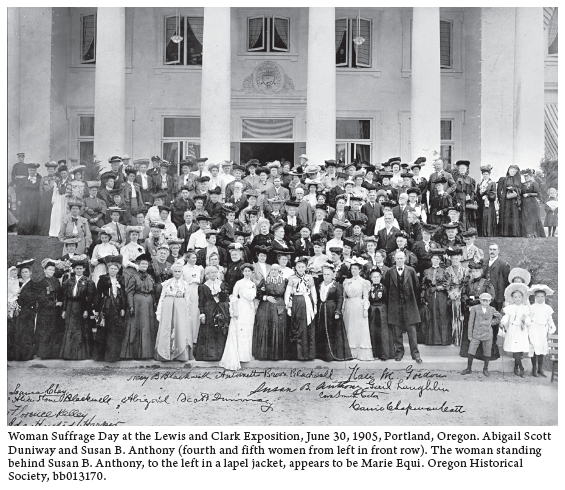

Suffragists had wanted to take a greater role in the planning of the exposition, but male directors of the operation blocked any significant engagement. Not to be dismissed altogether, feminists staged the annual NAWSA convention during the exposition. Nationally known suffrage leaders—Susan B. Anthony, Carrie Chapman Catt, and Anna Howard Shaw—arrived with hundreds of delegates intent upon winning the vote in Oregon the following year.36

The suffragists gathered at the First Congregational Church, a massive Venetian Gothic structure in downtown Portland designed to resemble the Old South Church in Boston. Yellow bunting, roses, and lilies framed the stage, and in front of the podium more flowers formed the word PROGRESS. Delegates sporting yellow ribbons—the color chosen for the suffrage campaign—were delighted with the hospitality of Oregonians, and optimism prevailed that the state would jumpstart the stalled national suffrage movement. Anna Howard Shaw, a licensed physician, ordained minister, and the new NAWSA president, stirred the audience as she refuted claims that suffrage would distract women from their duties as mothers and housewives. She was widely acclaimed as a brilliant, persuasive public speaker who lived and breathed the suffrage cause. But she struggled to manage the usual challenges for an underfinanced and understaffed advocacy organization riven with quarrelsome factions and impeded by cultural norms and political interests. Behind the scenes in Portland, NAWSA field workers tried to undercut Mrs. Duniway’s influence by establishing a rival organization. At the convention the national leaders offered to finance another Oregon campaign as long as they, and not Duniway, managed it. The conflict ensured a statewide effort with a festering dispute just below the surface.37

On the last day of the convention, Equi launched a short-lived campaign to be appointed to Portland’s new post of public market inspector. She described women as particularly suited for the job, and few doubted that the filthy conditions in the city’s markets required a strong hand. Equi won the support of NAWSA and that of the Oregon Equal Suffrage Association, and the Oregonian declared that Equi had “the strongest endorsement of any candidate.” She appeared poised for her first public office. But Portland’s new reform-minded mayor, Harry Lane, and the city’s board of health had already chosen Sarah Evans, the president of the Portland Women’s Club, for the post. Even before she was passed over, Equi pulled back from consideration. She sent a terse note to the mayor declaring she no longer wanted the job. She objected to the manner in which he had summarily dismissed the previous board of health members, including one of her woman doctor friends, and she charged the salary was woefully inadequate.38

On the same day the morning paper reported Equi’s turnabout on the post, a sensational story placed her in the midst of an apparent homicide. Mrs. Minnie Van Dran, a high-society personality and a personal friend of Equi’s, died after drinking ginger ale spiked with prussic acid. Investigators ruled out suicide, and Portlanders were abuzz for weeks with news of the investigation. Mrs. Van Dran was forty-one years old and the daughter of a prominent Albany, Oregon family. Her husband, Kasper Van Dran, was the proprietor of a Washington Street saloon in downtown Portland. In an unusual intervention, the Oregonian asked Mary Ellen Parker to determine the contents of the soda bottle. She and Equi found enough prussic acid to poison at least two hundred people. They also assisted with the autopsy and testified before the coroner’s jury. The police cleared the victim’s husband and sister, but they never solved the murder.39

The newspaper coverage of Equi’s role in the public market dispute followed by her assistance with a murder investigation of a friend—a mix of her political beliefs, personal life, and professional conduct—typified and shaped what Portlanders learned of her as she came to greater public attention. In the next eighteen months, however, first impressions would mean little as Equi garnered more public acclaim and notoriety than anyone would have imagined.