5

To the Rescue with the Oregon Doctor Train

Dr. Marie Equi: One of the most conspicuous examples of self-sacrifice in a desire to aid the suffering that has been seen in Portland.

Oregon Daily Journal

In November 1905, when Portlanders still glowed with the success of their world’s fair, Marie Equi encountered a woman who captured her imagination and swept her into a longtime intimate relationship. She fell in love with the refined and well-educated Harriet Speckart, heiress to a fortune. The two women first met at The Hill, a high-class residential hotel in Portland, where Equi and Mary Ellen Parker had begun residing earlier that year. Speckart, age twenty-two, her younger brother, Joseph, age seventeen, and her mother, Mrs. Henrietta Speckart, had also settled into rooms at the hotel.1

At first, Equi and Parker exchanged pleasantries with Speckart, her mother, and brother as they crossed paths to and from the hotel dining room. During the next few weeks, Equi spoke more frequently and privately with the younger woman, enough for Speckart to confide her deep longing to be free of her mother’s strict oversight. Equi and Parker commiserated with Speckart and drew her into a friendship that increased her desire to live independently. More importantly, Equi’s exuberance and charm delighted and captivated Speckart. Equi was ten years older and successful in her profession. She was intelligent and determined, and she loved a good time. In turn, Equi became increasingly enamored with the beautiful woman with long, blond tresses and a sweet, reserved, and unaffected temperament. She may have been intrigued by the prospect of a romance in which for the first time she was the older, more confident, and more experienced woman.

Equi and Speckart concealed their budding attraction from Mrs. Speckart as best they could. Equi was casual and cordial with her love interest’s mother, and, on occasion, partnered with her in card games. Behind the drawing room decorum, however, romance and passion flourished until Mrs. Speckart noticed her daughter’s flush of excitement in the company of her new doctor friend. She later described how appalled and panicked she felt over her daughter’s swooning for another woman. She immediately suspected that Equi was a gold digger after the family’s wealth. She tried and failed to discourage her daughter from seeing Equi again. Mrs. Speckart became so concerned with the affair that she abruptly gathered her family and departed Portland for San Diego in mid-December 1905. She told others she desperately hoped her daughter would come to her senses once separated from what she believed was Equi’s unhealthy, manipulating influence.2

The Speckarts’ wealth came from investments in breweries and real estate. When Harriet Speckart’s father, Adolph Speckart, died in 1893, he bequeathed his extensive estate to his wife and two children. Following her husband’s death, Mrs. Speckart traveled with her children to Germany to visit relatives, and Harriet and Joseph continued their education at private schools. Mrs. Speckart became accustomed to determining all matters that concerned her children, well past the time when her daughter came of age. In 1901, the Speckarts had returned to the United States and settled in San Diego for several years.3

Speckart missed Equi terribly and wrote to her every day from southern California, often slipping wildflowers into the envelope. She confided to a favorite aunt in Germany that “my doctor” wrote her almost as often. Her confidences to her aunt fairly glowed with the thrill of her new romance, and she expressed little reticence in disclosing her love for another woman. For Christmas, she wrote her aunt that Equi had sent a book of poems by Robert Browning and Elizabeth Barrett Browning and a gold chain with a heart-shaped amethyst. She later apologized to her aunt for not writing more frequently and explained, “. . . with people in love one has to have patience.” She blithely added, “It is a pity that Momma does not like her also.” Speckart seemed enlivened by the new possibilities in her life. She arranged to take piano lessons, and she hoped to learn Italian to converse with Equi in another language. On one occasion, Speckart responded to her aunt’s inquiry about marriage. “Yes, I am very happy single, especially now that I have Dr. Equi. I need no more, she loves me the same as I love her.”4

Equi wrote Speckart that her own busy days helped her endure their separation. She later recalled, “I was at the hospital from eight in the morning until noon, and I had a good practice at the time and was in my office from two until six every evening and after the evening hours I was called out and didn’t have a minute to myself.” Yet she managed to arrange a reunion with Speckart in San Diego by declining to represent Oregon at the national suffrage convention scheduled for Baltimore that year. In late February 1906, Equi took passage from Portland on the steamer Columbia bound for San Francisco where she intended to take another course in surgery and clinical work. During her weeks in the Bay Area, she wrote Speckart that she would stay with a “lady friend,” perhaps Bessie Holcomb. Two years earlier during a visit to San Francisco, Equi returned to Holcomb her own half-interest in their homestead property. The gesture may have been in appreciation for Holcomb’s help with tuition payments or as a belated wedding gift. Holcomb had married her employer, Alexander J. Cook, in 1903, two years after Equi departed for Portland. Equi finished her medical stint in March and continued to San Diego, where she and Speckart devised a plan for reuniting in Portland.5

By not attending the NAWSA gathering in Baltimore, Equi missed the last opportunity to see Susan B. Anthony alive. The venerable suffragist was taken ill while returning from the convention to her home in Rochester, New York, and she never recovered. Just hours before her death on March 13, 1906, at age eighty-six, Anthony confided her greatest regret to her longtime suffrage ally and chosen successor, Anna Howard Shaw: “To think I have had more than sixty years of hard struggle for a little liberty, and then to die without it seems so cruel.”6

During her final days Anthony worried about the outcome of Oregon’s suffrage vote and complained of the campaign expenses in the state. Her passing emboldened NAWSA leaders to commit more resources to the Oregon effort. Nine top officers and strategists departed for Oregon for the last two months of the campaign. They were heartened to find more than forty active suffrage clubs in the state with dozens of campaign committees and five thousand volunteers. The operation had become the well-coordinated, statewide effort that the “nationals” had long insisted was essential for victory. Their tactical opponent, Abigail Scott Duniway, resented the noisy commotion of the campaign, but she rallied local suffragists and delivered a rousing talk on the night before a national calamity halted all campaign plans.7

On the following day, April 18, the Oregonian published too early in the morning to cover the biggest story of the new century. Instead, Portlanders read the grim account of three African-American men lynched by a mob in Springfield, Missouri, and they followed the plight of two hundred thousand Italians left homeless and destitute after the eruption of Mount Vesuvius. Yet by midmorning, no one paid attention to anything but what news they could get from San Francisco. An operator of the local Postal Telegraph Company had suspected trouble as he completed his night shift. Just after five o’clock in the morning, his connection with San Francisco went dead. He queried the operator in Ashland, the southern Oregon exchange for north-south transmissions, but Ashland had been severed from the Bay Area as well. Eighteen minutes later the Sacramento office relayed the news from Chicago that San Francisco had been struck by the worst earthquake in California history, causing massive devastation and death.”8

During the next several hours, word of San Francisco’s earthquake traveled by word-of-mouth as Portlanders awoke. Telephones were rare in the city, and anxious throngs crowded telegraph offices and pleaded to send messages to loved ones in the Bay Area. But too few lines were open to accommodate their requests. The city’s commerce slumped, and the Oregonian noted, “The horror of it all turned men’s minds from business.” The disaster hit Portlanders hard across the board. As far back as the California Gold Rush of 1849, people in the state had been linked with their neighbors to the south. Able-bodied men had deserted Oregon towns to seek their fortunes in the gold trade, and farmers left behind thrived by providing provisions to the flood of gold-seekers in the Bay Area. By 1906, a great many Portlanders were San Francisco natives or had married into San Francisco families. Dozens of local businesses had begun in the Bay Area, and several civic leaders started their careers there. All these associations led to a pall of anxiety settling over Portland. Equi was in the thick of the worry with no word of her many relatives, friends, and medical school colleagues in the stricken city. She could rely only on the newspapers’ daily listing of those located or lost to the disaster.9

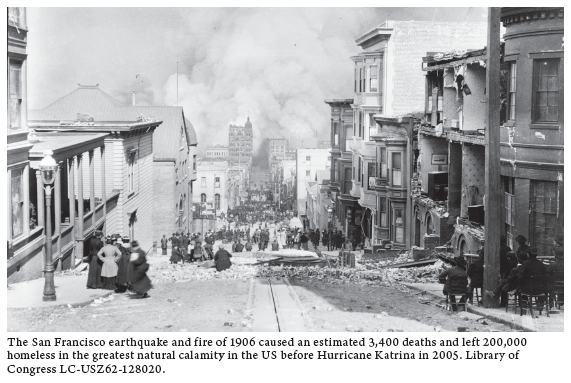

The great San Francisco earthquake and fire of 1906 remained the greatest natural disaster in the country for nearly one hundred years. The tragedy caused thirty-four hundred fatalities, left more than two hundred thousand people homeless, and leveled much of the nation’s ninth largest city. San Franciscans needed a massive amount of relief—food, clothing, medications, and housing—but no federal agency or private charity was equipped to respond to a crisis of that magnitude.10

As firestorms raged through the stricken city, communities nationwide rallied to help the disaster victims, but the people of Portland were the first to organize a comprehensive relief effort. The Rose City had the advantage of proximity—it was the closest large city after Los Angeles—and it had a direct rail connection to San Francisco. Portlanders also possessed the means to contribute both cash and supplies. Besides, business and civic leaders recognized the disaster as a threat and an opportunity. They feared the interruption of trade with San Francisco, and they relished the chance to demonstrate their big city status. Beyond resources, goodwill, and self-interest, Portlanders brought to the relief campaign decades of experience with civic betterment work, much of it planned and implemented by women through clubs and various social welfare organizations. Their experiences and the alliances they had formed positioned them to mount Portland’s most extensive humanitarian effort ever.11

By midmorning of the day after the disaster, the wives and daughters of Portland’s business leaders formed the Women’s Relief Committee for the California Sufferers, and they scrambled to gather supplies and medical personnel to send to the disaster zone. Their goals were remarkably ambitious: to equip a medical contingent for departure in twelve hours, collect bedding and clothing for thousands of San Franciscans, and organize for the ten thousand refugees expected to arrive in Portland within days. In short order, the committee secured a baggage car from Southern Pacific and a passenger car from the Pullman Company, and they canvassed wholesalers door-to-door for medicines, medical equipment, food, and clothing.12

To recruit doctors and nurses, the committee chose Dr. Kenneth Alexander J. Mackenzie, a leading surgeon and professor of clinical medicine at the University of Oregon Medical Department. At age forty-seven Mackenzie was well positioned for the assignment due to his service as the chief surgeon for the Oregon Railway and Navigation Company, the local operator of the Southern Pacific line. Mackenzie sought doctors and nurses at the city hospitals, offering them nothing but the chance to serve on a two-week mission. Although he warned volunteers they would endure hardship and face exposure to contagious disease and civil unrest, Mackenzie easily met his quota of doctors and nurses and turned away others.13

Equi was quick to volunteer, and she was the only woman doctor on the Oregon relief mission. Just three years out of medical school, she might have seemed an unlikely choice, but having a woman physician supervise and lodge with the nurses made sense. Mackenzie also knew Equi firsthand. She had taken two years of his anatomy classes, and she had worked with him at the hospital. Most importantly, she was willing.

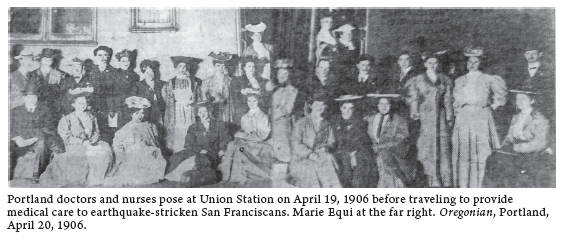

In just ten hours the relief committee garnered twenty tons of supplies—chloroform, ether, disinfectants, hot water bottles, splints, and gauze—as well as the few medications available such as morphine, digitalis, and strychnine. The forty-two doctors and nurses of the mission gathered at Union Depot for the 8:45 evening departure. Equi was accompanied to the sendoff by Mary Ellen Parker. All the volunteers were dressed in proper traveling attire—the women in floor-length dresses and coats with broad, swooping hats and the men in suits and bowlers. Except for the red crosses pinned to their sleeves, they appeared to be en route to a convention or the opera season in San Francisco. The Southern Pacific cars, soon dubbed the Doctor Train by the local press, steamed away from the station on schedule, crossed the river, and rolled into the night.14

With the mission underway, Mackenzie took no chances with the city’s reputation or his own. He presented Equi and the others with a written loyalty oath that placed the mission under “the orders, authority and discipline of the Government of the United States as prevailing under martial law in the City of San Francisco.” (Although the Bay City was never placed under martial law, almost everyone at the time believed it had been). None of the volunteers objected and everyone signed.15

The medical corps received few accounts of the disaster while they traveled. The fires continued to rage as they left Portland, so hot that San Franciscans dodged cobblestones popping from the street and watched whole buildings incinerate in seconds. Sixty miles north of San Francisco the relief team first viewed earthquake damage when they rolled past flattened farm houses. At ten miles from the city the heavy stench of smoke was unavoidble. United States Army officers met the doctor train once it eased into the Oakland Mole near the foot of Seventh Street today. From there Equi and the other medics boarded a military steamer to cross the bay. Only that morning, three days after the earthquake, had the fires been stopped. In the early light of the day, the city lay blackened by fire with thirty thousand buildings and nearly five hundred city blocks destroyed, including the area of today’s Financial District, Civic Center, much of South of Market, and fiery intrusions into the Mission District and along the edge of the Western Addition.16

The steamer pushed west past San Francisco’s waterfront and approached the fog-bound Presidio, the US Army base at the northern tip of the peninsula. There the medics reported to military officers of the army’s general hospital. The Oregon corps found the base functioning remarkably well given the damage to the hospital, power plant, and supply depot. Almost immediately, the army had accepted injured and panicked civilians fleeing the firestorms in the city. Their first evening in San Francisco, Equi, Mackenzie, and the others were integrated into the army’s relief operations, each assigned to specific duties under the command of a military medical officer. A dozen of the young male Oregon doctors undertook the basic grunt work of public health—digging trenches and setting up latrines—at two refugee camps. Whatever visions they held of heroic service in the adventure of a lifetime were quickly dashed in the ditches. Lieutenant Colonel George H. Torney, the officer in charge of enforcing strict sanitation measures in the city, directed Mackenzie to establish a contagious disease hospital near the Presidio. Mackenzie anticipated a surge of infectious diseases—measles, chickenpox, scarlet fever, diphtheria, and mumps—but no epidemic swept the city. Mackenzie told a reporter that the efficient, if disagreeable, work of the sanitary corps saved San Francisco from the “worst scenario.”17

Equi and the Portland nurses began their duties at the Presidio’s hospital, a three-hundred-bed facility built in 1898. They worked with a dozen army doctors and forty army corps nurses unaccustomed to treating civilians, and they struggled to handle more than 350 refugees. Most patients presented with intestinal problems, sprains, or burns brought about by stress, shock, and the sudden exposure to outdoor living. But for many the physical ailments disguised the psychological impact of losing loved ones, homes, and livelihoods.18

The army charged Equi and her contingent of nurses with obstetrics care, and their unit became known as the “Oregon ward.” The design of the army hospital permitted nurses as well as patients to get fresh air in wide corridors, called galleries, open on one side and glassed on the other. But Equi and the nurses worked long days, often with only snatches of sleep, and rarely had time to enjoy the view of ships coursing through the Golden Gate.

Newspaper reporters from Portland were eager to file stories from San Francisco, and they found in Equi a ready source of copy. A week after her arrival she recounted how the disaster seemed to have had no ill effects on the twenty-three newborns delivered at the Oregon ward. The infants were thought to be the first born in a military hospital in the United States, and Equi declared them among the healthiest she had encountered in a long time. A few days later, a fire broke out near the ward in the early morning hours, and Oregonians read about Equi’s rescue of the patients. She raced to them with a wheelchair, wrapped each mother and infant with a blanket, eased them into the chair, and wheeled them out of danger. Equi described the quiet, stoic demeanor of the two dozen mothers with an eloquence seldom found in the newspaper.

All the agonies and tortures those poor mothers had suffered before they had been brought to the hospital had so deadened their senses, so numbed their minds, that they faced the fire horror with a spirit of calmest resignation and without fear. They had already suffered too much to suffer more.19

The Oregon Daily Journal featured another piece titled “Dr. Marie D. Equi Seizes a Motor Car.” In that account, Equi left the Presidio hospital one day for a trip into the city, but she was later unable to arrange a return. Carriages and horses were hard to come by, and automobiles were rare in the city, especially after the army had appropriated so many for emergency transport. Equi hailed to a stop one gentleman being driven about by his chauffeur and directed the driver to take her to the hospital. When he refused, she appealed to a nearby soldier who ordered the owner and the driver to accommodate her. Equi settled herself nicely on the cushioned seats and cheerily waved to onlookers as she rolled away.20

For all the difficulties of disaster duty, Equi thrived at her post. She managed her duties well and experienced no problems under army command. She also enjoyed the company of another single, professional woman, Gail Laughlin, who had managed to pay her own way on the doctor train from Portland. At age thirty-seven she was a talented lecturer and organizer from Maine who left her New York law practice to work fulltime on woman suffrage with NAWSA. She then helped organize the Oregon campaign and lectured throughout the state. At the time of the earthquake, Laughlin had no medical training to warrant her trip to San Francisco. Her interests appeared to lay closer to the heart. Her intimate companion, Dr. Marguerite (Mary) A. Sperry, lived in San Francisco, and Laughlin’s only way to confirm Sperry’s well-being was to travel there. She was much relieved to find Sperry safe. On their third night in the stricken city, Equi and Laughlin walked to the damaged Ferry Building from the Presidio grounds and listened to the military band. The sky was dark with no city glow since gaslights were not permitted. Laughlin later recalled they were unable to walk on the sidewalks because they remained too hot from the fire. “Any description of San Francisco is beyond words,” Laughlin later told the Oregonian. “It was hard for us to get over the feeling that we were not walking among the ruins of some ancient city that had been dead for a thousand years.” She remarked on the orderliness in the city with people being so generous and helpful to one another. Laughlin soon returned to Portland to resume her suffrage work, and, after the campaign, established a law practice first in Denver and then in San Francisco. Laughlin lived with Dr. Sperry in a lesbian relationship until Sperry’s death in 1919 and later served in the Maine state legislature.21

San Franciscans who took refuge in the hospitals and camps voiced so much appreciation for the work of the Oregon medics that the volunteers felt blindsided by the fierce criticism several local physicians lobbed their way. Less than two weeks after the Oregonians arrived, a San Francisco doctor disrupted an emergency meeting of five hundred local practitioners with a demand that the Oregon corps leave the city at once. He complained that they were unneeded and unwanted and that their very presence threatened the livelihoods of local doctors.22

Dr. Mackenzie attended the meeting and bristled at the charges, especially since he had tried to ease the relocation of local doctors to other states and had pledged one hundred dollars of his own money to a fund for their benefit. Equi was also present for the proceedings, and the San Francisco physician who filed the complaint, Dr. Henry Kugeler, had been a professor of hers at the University of California. She told a reporter afterward that the resolution was meant for all outside physicians not just those from Oregon. Nevertheless, she noted that the resolution “nearly precipitated a riot.” She castigated the California physicians for first criticizing outsiders and then asking for help obtaining medical books, supplies, and instruments to restart their businesses. “You never saw such a disorganized band of men in your life,” she complained. “They were unfit for work and were helpless to meet the situation. Without outside assistance the terrors of the situation would have been multiplied many-fold.”23

Mackenzie and Equi misread the frustration that fueled the rebuke. The motion was eventually tabled, but the resolution made sense. The Oregon medics had rallied without being invited, and they departed Portland too quickly to be informed that the California governor had advised doctors and nurses not to rush into the state. Hundreds of local providers feared for their livelihood with their offices and equipment destroyed. They had already lost clients —the wealthy ones sought refuge outside the city and the poor enjoyed free medical care at makeshift clinics and hospitals.24

The sting of the criticism was lightened by effusive praise from elected officials and army officers. California Governor George C. Pardee thanked Oregon for its rapid response in sending aid and personnel to his state. He singled out Equi and Mackenzie for doing so much “at a time when we were practically helpless.” San Francisco Mayor Eugene Schmitz recognized the “magnificent spirit of philanthropy” shown by so many Oregonians. The commanding officer at the General Hospital presented Equi with a medal and a commendation on behalf of the US Army. The citation read, “Your manifestation of executive ability has been marked, and the conduct and services of the corps of nurses under your charge has been uniformly satisfactory in every degree.” According to a Portland newspaper, Equi was only the second woman physician detailed for service at a US General Hospital.25

With the conclusion of their two-week commitment, the Oregon volunteers prepared to leave. Under a mandate from President Theodore Roosevelt, the American Red Cross took charge of relief operations as its first major disaster relief operation. The Oregon physicians relinquished their posts, and the doctor train departed Oakland for Portland on May 5. Equi, however, extended her stay an extra week, probably to view the full damage and to visit her relatives and friends.26

Eighteen days after the earthquake struck, a resurgent city began to take shape. The Ferry Building and much of the Mission District were once again lit with electricity. Nearly all the trolley lines operated, but a ride along Market Street revealed how massive a reconstruction effort faced the city. Empty, charred steel frames stood block after block amid vast piles of debris on ragged, cracked sidewalks. Many of Equi’s personal landmarks in the city had vanished in the firestorms, including her first residence on Market Street, her second home and the nearby St. Ignatius church, her first medical school, and the county hospital where she had interned.

San Francisco was not completely devastated, and most residents survived both the earthquake and fire with minimal losses or harm, including Equi’s relatives, colleagues, and friends. Her professional associates were unharmed, but they mourned the extensive damage to the newly built Hahnemann Hospital, completed just eight days before the earthquake. Bessie Holcomb, her husband, and their one-year-old son survived the disaster as well, and their home on Divisadero Street remained intact. However, firestorms in the city’s waterfront district destroyed her husband’s leather goods business.27

Equi returned home and found Portlanders justly proud of their humanitarian work. In a few weeks, they had collected more than $250,000 in cash for earthquake sufferers. Citizens stepped forward to provide assistance on a scale the government was unable to muster. Unlike several California cities, Portland accepted Bay Area refugees without fear or precautions against “the wrong kind” flooding into the city, and more than five thousand people stopped in Portland. Residents provided them with food, clothing, and medical care.28

Although disaster news no longer filled the front pages of Portland newspapers, the Evening Telegram heralded Equi’s arrival and touted her as “one of the hitherto unsung heroines of the San Francisco disaster.” Equi deflected the praise to Mackenzie’s leadership and to the exceptional service of the nurses under her care. She suggested that their names “should be emblazoned on a roll of honor so that all might know of what sort of stuff our Oregon daughters are made.” In her absence the local papers had doted on Equi and her relief work with nearly twenty articles in as many days, more than for any relief doctor other than Mackenzie. The Oregon Daily Journal ran an effusive piece that anointed Equi as “one of the most conspicuous examples of self-sacrifice in [a] desire to aid the suffering that has been seen in Portland.” The article also touted Equi for giving up a successful practice to work nonstop amid “all kinds of danger.”29

The newspapers’ extensive coverage of Equi reflected more than appreciation for her humanitarianism. Her distinction as the only woman doctor on the mission made Equi good copy for the Oregon reporters working in San Francisco. She also knew how to tell a good story, and she understood how to engage reporters and provide them with ready content. But the relief mission occurred in the midst of heated public debate over women’s role in society, and women were pushing for the right to vote in the upcoming Oregon primary. A majority of male voters repeatedly balked at the idea of women taking charge of their lives and engaging matters in the public sphere. By touting the courage and service of one professional woman, the press and civic leaders appeared supportive of women even while they continued to resist their full voting rights. Nevertheless, the public acclaim had to be deeply satisfying to Equi. Thirteen years earlier a newspaper had proclaimed her Queen for Today for her righteous justice on the streets of The Dalles. Now as a result of her relief work, people in Oregon as well as many in California read of her generosity, compassion, and good humor as well as her clinical and management skills. In her newly adopted city, Equi could feel less an outsider—if only for a while.