14

Days of Reckoning

If ever an individual needed protection for free speech, free press, and free conscience, it is in time of war. People don’t need constitutional guarantees at their picnics and prayer meetings.

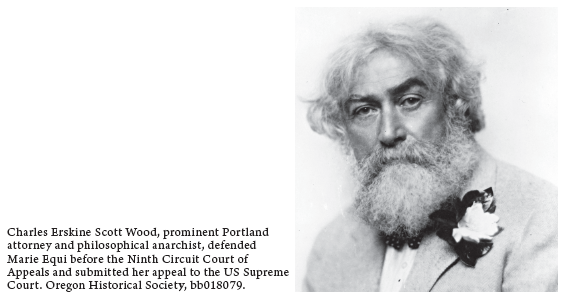

Charles Erskine Scott Wood, attorney for Marie Equi

America was a transformed country after the wrenching experience of World War I and the ravages of the Spanish flu. The nation struggled to accommodate the returning soldiers and sailors seeking employment as well as the women and African Americans who wanted to keep their wartime jobs. Accustomed to government protections during the hostilities, industries resisted returning to greater competition and less-favored treatment. Women sought the long-delayed federal action on their right to vote, and Progressives and liberals lobbied for restoration of free speech and other civil liberties.

In Oregon, business activity in 1918 shattered previous records. The Oregonian proclaimed that every man who wanted a job could find one with unparalleled wages. Yet the region had also experienced one of the nation’s most vigorous clampdowns on dissent, and the strife it caused hardly skipped a beat for the armistice. In addition, the federal and state governments inflamed a new postwar hysteria, stirring Americans’ fears of radical immigrants and Bolshevik revolutionaries. A new Red Scare gripped the nation, and radicals like Marie Equi found little peace at war’s end.1

Equi’s conviction was one of hundreds delivered to radicals. In the mass trial of forty-six Wobblies in Sacramento, twenty received ten-year sentences, and all but three others were sentenced to terms of three to five years. The Omaha Roundup of sixty-four Wobblies was eventually dismissed, but not before the men had spent eighteen months in jail.2

Equi hoped the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals in San Francisco would overturn her conviction, and she retained attorney James Fenton and, this time, C. E. S. Wood as her counsels. Wood, at age sixty-seven, had hoped to retire in San Francisco with his mistress, Oregon poet and suffragist Sara Bard Field, rather than tackling the US government’s assault on free speech. But he found the wartime acts offensive to his personal and political beliefs, and he knew Equi well. In April 1919 he fired off a letter to the US attorney general, A. Mitchell Palmer, and objected to the government’s use of the courts to silence Equi. He asserted that the charges against Equi accommodated “the privileged, wealthy classes of Portland and those who consider existing conditions sacred.” President Woodrow Wilson had named Palmer, a Quaker-reared Progressive who never served in World War I, to the nation’s top law enforcement post a month earlier. Palmer never responded to Wood’s message, and Equi’s attorney prepared for an appeal hearing in June.3

Equi’s conviction failed to appease federal authorities in Oregon. As long as she remained free, they tried to silence her. Agent Bryon fumed in his reports to Washington about the public criticism of his courthouse clash with Equi, and he retaliated. An informant reported to him that on December 25, 1918, the local IWW had admitted Equi and Kitty O’Brennan—Number 439091 and Number 439090, respectively—as honorary members working on recruitment strategies. Bryon used the information first against O’Brennan to help deport her for working on behalf of Sinn Fein, the Irish revolutionary group. On January 14, federal authorities arrested O’Brennan at the Oregon Hotel. The Oregonian headlined the occasion with reference to her relationship with Equi: “Woman Who Shared Room with Dr. Marie Equi Taken Into Custody by Immigration Inspector.”4

At O’Brennan’s deportation hearing, government officials interrogated her about Sinn Fein and whether she favored the violent overthrow of British rule in Ireland. She denied raising money for the radical group but championed Irish freedom, no matter how it was achieved. After repeated questioning, she admitted to being an honorary IWW member. O’Brennan was released on her own recognizance, and a report of her hearing was submitted to officials in Washington, DC. Perhaps as a result of O’Brennan’s connections with US senators, nothing further came of her case.5

Equi’s own IWW membership—honorary or not—made her guilty of violating a new Oregon law meant to accomplish in the state what the Espionage and Sedition Acts had achieved nationally. Oregon and twenty-eight other states had enacted antianarchy laws—popularly known as criminal syndicalism acts—that prohibited utterances or publications that might trigger discontent or hostility toward the US government. In addition, any participation with the Socialist Party or the IWW violated the law. The US attorney general advised against prosecutions based on simple association with radical organizations, but local authorities, including state supreme courts, embarked on guilt-by-membership sweeps of suspect citizens. Fear of radicalism spiked across the nation, partly in reaction to the Great Steel Strike and the nation’s first general strike in 1919. A walkout of 360,000 workers disabled the steel industry, and 60,000 local laborers shut down the city of Seattle for nearly a week.6

Portland police arrested Equi just before midnight on March 13, 1919, for violation of the state’s criminal syndicalism act. She was charged with asking two men, a woman, and a girl to help her distribute Wobbly literature on downtown streets. After a night in jail, she was released for lack of evidence. Her detention reflected how authorities used the new law to exhaust radicals with arrests and jail time before reducing charges against them to misdemeanors.7

Equi left Portland for San Francisco two weeks later to take her case to the public under an arrangement with the Mooney Defense Fund. By aligning her circumstances with those of the internationally known prisoner of San Quentin, Equi gained a stature far greater than what she had achieved in Portland. She was thwarted from talking at Eagle’s Hall in the city when the building owners learned the IWW sponsored her appearance, but she drew three hundred people at another location on Market Street and collected more than one hundred dollars.8

At an Oakland appearance, she challenged the audience to undertake nothing less than a widespread strike to free the thousands of political and class prisoners. “Political action is as dead as a Dodo—you can’t do anything with it unless you have industrial organization first,” she declared. She also spoke of class struggle. “You do not realize the class fear and the class hatred that is felt right now by the capitalist class. Talk about our class hatred. It is a puny affair next to their class hatred.” Back in San Francisco, Equi reunited with Margaret Sanger, who was seeking solace in California after a bout of depression over the imprisonment of dissidents and the stalled efforts of the birth control movement.9

Equi’s reckoning before the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals came on June 4, 1919, in San Francisco’s federal courthouse, the same location where Harriet Speckart’s case had been heard years earlier. Equi appeared with her attorneys, Wood and Fenton. Kitty O’Brennan and six women supporters from the Bay Area, including Charlotte Anita Whitney, accompanied her. US Attorney Haney and Assistant Attorney Goldstein reappeared to defend their case before three judges led by William W. Morrow, a seventy-six-year-old Republican jurist with previous service in the Union Army and the US House of Representatives.10

Equi’s attorneys reiterated that her activities prior to the Sedition Act should not have been admitted as evidence. They faulted Judge Bean for failing to protect her and claimed that she had become tainted before the jury as a result. In his remarks before the court, C. E. S. Wood presented a more profound argument. “If ever individuals need protection for free speech, free press, and free conscience, it is in time of war,” he said. “People don’t need constitutional guarantees at their picnics and prayer meetings.” He argued that it mattered little if people found Equi disagreeable or if they found her speeches obnoxious. There was no treason, he said, in speaking one’s mind.11

Wood knew that the circuit court judges were influenced by the Supreme Court’s Schenck v. United States decision three months earlier. In that espionage case, Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes presented the situation of a man falsely shouting “FIRE” in a crowded theater as an example of limits to free speech. He established the clear and present danger test for utterances that Congress has a right to prevent. Wood countered that the fire-in-a-theater argument was irrelevant to a citizen criticizing her government since there was neither a threat nor damage to others. Instead, he countered, the US government, the press, and the moneyed classes had inflicted moral and political damage on the American public. One of Wood’s biographers notes that his arguments were remarkable for assailing not only the political culture of the time but also the officers of the goverment, including the judges of the circuit court and the US Supreme Court.12

Attorneys Haney and Goldstein asserted that the war had required new demands of citizens. “We had to have men, we had to have money; and to get men and money, we had to have the proper spirit,” Haney claimed. They reminded Judge Morrow of his previous finding that statements delivered prior to the war were clearly admissible. They claimed to confine their arguments to the record but then resorted to criticizing IWW and Socialist views and to deriding Equi for her “pose of martyrdom.”13

The judges took the case under advisement, and Equi returned to Portland with O’Brennan. But she seemed unable to stop and rest for long. She traveled to Seattle and stood before fifteen hundred people to raise funds for those not fortunate to be released on bail. She made a point of identifying eight other women who faced terms of two to twenty years: Mollie Stimer, Flora Foreman, Louise Olivereau, Emma Goldman, Elizabeth Baer, Rose Pastor Stokes, Theodora Pollock, and Kate O’Hare. She understood how much these women, and many others, had upended gender norms of political power to protest the war and unjust labor conditions.14

Equi’s life revolved around more than legal struggles and her expected imprisonment. Ruth Barnett, a younger abortion provider trained by Equi’s friend Dr. Alys Griff, recalled long nights of partying. The three women worked in the Lafayette Building in three office suites and lived in the old Oregon Hotel, a few rooms apart.

“We worked hard and played hard,” she later wrote. “After work we would whoop it up until all hours of the morning. . . . We’d go out to the roadhouses—Twelve Mile or the Clackamas Tavern. The doctor (Alys Griff) always had a big car, either a Winton or a Pierce Arrow. We had some great times. When you work hard, you appreciate the laughs, the big dinners, and the booze.”15

Equi’s drinking flew in the face of the Progressive Era’s ban on alcohol sales and consumption in Oregon enacted in 1914. She had earlier regarded alcohol a threat to family life and individuals’ well being, but, considering her looming imprisonment, she allowed herself some liberties.16

When Equi was fighting her conviction in San Francisco, senior staff at the Bureau of Investigation in Washingon D.C. questioned the merits of her case. A special assistant to the attorney general, Alfred Bettman, believed the charges were “the product of clamor rather more than truth.” “I would certainly recommend dismissal of the prosecution,” he advised if the circuit court reversed Equi’s conviction. But three weeks later, on October 27, 1919, the Ninth Circuit Court affirmed the lower court’s decision. They relied on precedents in other espionage cases and dismissed claims of First Amendment rights. Equi had partly expected the outcome, but she was staggered by the news nevertheless. “We’re slaves,” she told a gathering in downtown Portland four days later. “We may think we live in a free country, but we are in reality nothing but slaves.”17

Only one legal option remained: a final appeal to the US Supreme Court. For this, Equi once again retained C. E. S. Wood with her own funds supplemented by $300 from Alexander Cook, the San Francisco merchant and husband of Bessie Holcomb, her longtime friend from New Bedford. She also recruited attorney Helen Hoy Greeley, an ally from Oregon’s 1912 suffrage campaign, to lobby on her behalf in Washington, DC. They expected a decision from the nation’s highest court at the start of the New Year.18

The clampdown on dissenters in America continued to surge, and radical suffragists were not spared the public’s wrath. In Washington, DC, angry mobs attacked National Women’s Party members who picketed the White House every day during the early months of 1919. They challenged President Wilson and Congress to ensure liberty for America’s women as they had for European allies. The demonstrations led to arrests and beatings followed by hunger strikes and forced-feedings in prison. When the women were released, they toured the country by rail on a “Prison Special” to shame the government and further their cause. Congress finally submitted a federal suffrage amendment to the states in June 1919. More than a year later, on August 18, 1920, the amendment was ratified by two-thirds of the states and became enshrined as the Nineteenth Amendment to the US Constitution.19

A new free speech fight flared in the Pacific Northwest in November 1919 and drew Equi into its aftermath. A riot erupted between the American Legion and the IWW in Centralia, Washington, eighty-five miles south of Seattle. During the city’s Armistice Day Parade, a platoon of American Legionnaires stormed the local Wobbly headquarters. Expecting an attack, Wobblies opened fire against the intruders, leaving three men dead and others wounded. One of the Wobbly shooters, Wesley Everest, a five-foot-seven-inch, thirty-three-year-old with dark red hair and blue eyes, ran from the scene and then reportedly shot and killed a Legionnaire who charged toward him. A mob captured Everest, beat him, and, according to eyewitnesses, rammed a spike through his cheek and broke his jaw before throwing him into jail. Later that night the men returned, pulled Everest from his cell, and hung him from a railroad trestle over the Chehalis River. Everest’s death, and the trial of Wobblies charged in the battle, became yet another widely watched and much-condemned episode among labor radicals. George Vanderveer, Equi’s recent attorney, mounted a defense, but most of the Wobbly defendants were convicted and sentenced from twenty-five to forty-five years in prison. Charges were never filed for the killing of Everest.20

Equi later told her daughter that she had visited the Wobblies in Centralia before the violence erupted and had tried to persuade Wesley Everest to leave the city while it was still safe. After Centralia, the Justice Department conducted another assault on radical organizations. Beginning November 7, 1919, in what became known as the Palmer Raids, named for the US attorney general, federal officers conducted mass arrests in thirty cities, including Portland, in an attempt to deport suspicious aliens and stifle antigovernment protests. The ongoing suppression of dissent demoralized radicals, and Equi wrote to Hanna Sheehy-Skeffington, her Irish nationalist friend in Dublin, that she was unable to give any talks because every assembly hall owner in Portland was threatened with arrest if a space was rented to her or to any other radical. Equi also felt badly, she wrote, about the attempt to deport Kitty O’Brennan. “Her arrest was brought about because she fought so hard for me . . . besmirching her took the spirit out of me somewhat.” Equi continued to push for Irish independence, and she may have met Sinn Fein leader Eamon de Valera during his November 1919 visit to Portland. After de Valera’s visit, Equi enlisted O’Brennan to lobby for her in Washington, DC, and to work with her attorney there. O’Brennan’s trip east marked the end of the intense, intimate relationship that she and Equi had shared for eighteen months.21

As expected, the Supreme Court gave Equi no relief, and on January 26, 1920, the justices denied her request for review. Newspapers across the country carried the news, with the San Francisco Chronicle describing Equi as “the central figure in more episodes of turbulence in cities along the Pacific Coast for five years than any other woman.” On a dreary day when more rain fell in Portland than at any time since 1903, Equi told the press, “Just what I expected. I am made to suffer for something I never said.” She added, “I am no more guilty of the charges that take me to prison than is an unborn babe.” She concluded that all she could do was await the start of her three-year prison sentence, but she actually kept fighting.22

Even before the Supreme Court decision, Equi initiated a new strategy with an appeal to President Wilson’s secretary, Joseph Tumulty, to help her obtain presidential clemency. In a four-page letter remarkable for its straightforward portrayal of her situation, Equi declared her conviction resulted primarily due to the enmity of General Brice Disque, leader of the US Army’s Spruce Division in Pacific Northwest forests. “I had dared to call attention to the failure of General Disque to do certain things to maintain an efficient morale among the workers and thus speed up production,” she wrote. She claimed that Disque had told others he wanted to see her indicted and jailed. She also described how the two prime witnesses in her trial appeared incompetent to complete their task. She reiterated for him how they had agreed before the trial to “put words into her mouth” that would sound as damaging and disloyal as possible.”23

Equi also detailed how the prosecution maligned her “private moral character.” She charged that her same-sex preferences motivated federal agents and the US attorneys in Portland to mount their campaign against her. No other known lesbian convicted of federal offenses had presented such arguments to the nation’s executive office. She wrote of the harassment inflicted on her—the wiretaps, the holes drilled through her doors, and the surveillance and intimidation of everyone with whom she came in contact. She closed with a complaint about Agent Bryon’s physical assault on her, her companion, and her young daughter. She asked Tumulty simply for an examination of the testimony against her. She said she believed she deserved that much as an American citizen.24

Equi’s friends and allies flooded the White House with letters and telegrams in support of clemency. Portland supporters sent a petition for a presidential pardon to Senator James Phelan of California who then conveyed it to the president. Thomas Gough Ryan, a former deputy district attorney of Multnomah County, wrote one of the most persuasive letters to the President. He declared his absolute opposition to the IWW and “all forms of radicalism” as well as his full support of the Espionage Act. Ryan was also an officer and active member of the Four Minute Men, the speakers’ bureau that promoted voluntary registration during the war, and a host of other patriotic causes. He had known Equi for many years, he advised Wilson, and if she had made mistakes, they were “of the head rather than of the heart.” He concluded, “I am firmly of the opinion that it would be a crime and an outrage to send Dr. Equi to jail, even for a day.”25

Mary Frances Isom, Portland’s librarian who had become embroiled in a patriotism dispute herself, added her plea for a presidential pardon, not just for Equi but for everyone caught up in what she described as “imprisonment for politics.” An indication of Equi’s influence beyond Oregon came with a letter from the wealthy and prominent Tammany Hall leader J. Sergeant Cram of New York. He wrote Attorney General Palmer that Equi had many influential friends in New York whom he would like to oblige. He dismissed her offense as “comparatively trivial” and advised, politician to politician, that “no public interest will be sacrificed by the exercise of clemency in her case.”26

US Attorney Haney and Judge Bean, who had presided over Equi’s case, attempted to counter the appeals from Equi’s supporters. Haney declared to federal authorities that he “vehemently opposed clemency.” The lobbying efforts, pro and con, captured the attention of the Department of Justice, and J. Edgar Hoover, the new head of what became known as the “Radical Division” of the Bureau of Investigation, requested a detailed memorandum about Equi’s activities. Hoover would become FBI director in 1924 at age twenty-nine and maintain a fierce grip on the agency for forty-eight years until his death in 1972. He presented himself as a smart, cool operator, who modernized the agency even as he drove it into a morass of constitutional abuses and criminal acts. Historians have conjectured, and disagreed, whether Hoover maintained a longtime, closeted homosexual relationship with his deputy, Clyde Tolson, but there he was, nevertheless, requesting information about a lesbian who offended authorities by living her life openly.27

For several months in early 1920, Equi’s attorney, Helen Hoy Greeley, labored in Washington, DC, over the application for a presidential pardon. The inordinate amount of effort required to complete the request led her to ask President Wilson for three separate sixty-day reprieves of the filing deadline. So much time transpired that even First Lady Edith Wilson expressed exasperation, writing to one of Equi’s supporters in late August 1920 that “every opportunity is being given Dr. Equi to be heard fully,” but “nothing can be done” until the application was submitted. When Greeley finally completed the one hundred–page document, Elizabeth Gurley Flynn—on behalf of the IWW Workers Defense Union—paid for its preparation.28

Several weeks later Equi was down to the final hours of her last reprieve from prison, and no one expected the president to grant a fourth delay. Attorney Greeley later revealed to Equi how close they had come to getting what they wanted. At the last moment before submitting a department recommendation, both the US pardon attorney and the assistant attorney general (who previously argued against Equi before the Supreme Court) had advised a full pardon. Attorney General Palmer himself shot down his subordinates’ advice, according to Greeley. The night before Equi’s last reprieve expired, Palmer wired Portland authorities that Wilson had commuted Equi’s sentence from three years to one year and a day in a penitentiary to be determined.29

From the government’s standpoint, a commutation reduced the length of punishment without any expression of forgiveness or fault by authorities. But Equi proclaimed the move as a victory. “I’m going to prison smiling,” she told the Portland dailies. “But I am not through. I shall keep on fighting until I die.” She was keenly aware that her struggle was just one among many. “When they keep an old man like [socialist leader Eugene] Debs in prison—at 63 years of age—I have no complaint to make. There are better people in jail than I am.”30

Equi was allowed a final night of freedom October 14, and she and her friends no doubt tapped her supply of bootleg liquor for the occasion. On Friday morning she appeared before Judge Bean to ask for extra time to get her affairs in order, but he turned away the request. She agreed to appear at the US marshal’s office that afternoon. From there she would be escorted to jail to await her trip to prison.31

Two dozen friends accompanied Equi that afternoon. She carried a bouquet of red roses and walked beside five-year-old Mary Jr., who held Harriet Speckart’s hand. Only that morning did Equi learn she would serve her time at San Quentin California State Prison in Marin County. (The federal penitentiary at McNeil’s Island had been another option but it was not equipped for female inmates). The choice suited her, she said, much more than the women’s reformatory in Rockville, Iowa. “I am too old to reform,” she quipped. Her friends said goodbye at the jail. Her departure was widely covered in local and national media, including La Tribuna Italiana, Oregon’s only Italian-language newspaper. To the Oregon Daily Journal, she spoke of her daughter: “I’ve had that little girl since she was three weeks old. She is as dear to me as if she were my own child.” And she spoke of being humbled at “the wealth of friendship” extended to her that morning.32

Equi’s transport to San Quentin was delayed several hours, but on Sunday, October 17, 1920, at 11:30 p.m. Southern Pacific No. 10 departed Union Station for points south. A US deputy marshal and a police matron who Equi knew well from her previous arrests accompanied her. Her sentence would not begin until she was received at San Quentin, and she wanted to get it started as soon as possible.33