18

Queen of the Bolsheviks

I see her as . . . a woman of passion and conviction . . . a real friend of the have-nots of this world.

Julia Ruuttila, longtime Oregon labor activist

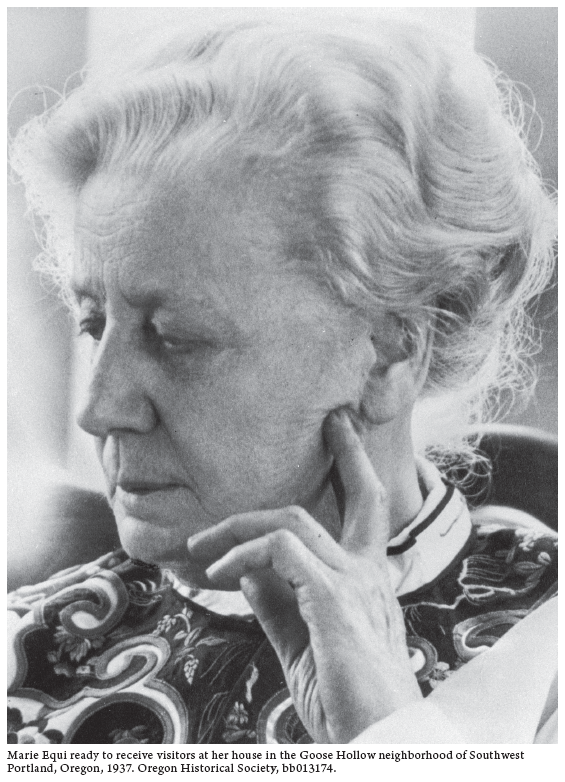

A tonic for Marie Equi’s bruised spirits after Mary’s elopement and Elizabeth Gurley Flynn’s departure appeared early in 1937 with the publication of an article that treated her antiwar protests with respect. Stewart Holbrook, a popular and prolific newspaperman, featured Equi in an eight-part series in the Oregonian on episodes of mass hysteria in the Pacific Northwest. Holbrook challenged Oregonians’ beliefs that they were too solid of character to succumb to “public fevers.” In the installment “Down with the Huns,” he detailed the hyperpatriotism that engulfed the region in the World War I era. “The jails of every town and city in Oregon and Washington were soon full to bulging with Wobblies, young and old, native and foreign-born,” he wrote. Holbrook described ordinary citizens, including Equi, whom the government harassed and defamed for exercising their right of free speech. Equi’s enemies, in Holbrook’s estimation, sent her to prison although they had “never accused her of anything much worse than honesty.” Beneath a photo of her, the caption read, “Dr. Marie Equi was sentenced for saying what she thought of the big barbecue.” Equi appreciated the even-handed tribute, and she thanked Holbrook in a note, “The line under the photo was very effective. You are writing trenchantly in your Sunday articles.”1

The good press from Holbrook may have lessened Equi’s indignation at having her reputation for radicalism overlooked on another occasion. When Portland’s repressive Red Squad published a list of important radicals living in Portland, she was incensed to find her name missing. The Portland Police Bureau had long operated the Red Squad—a right-wing cadre dedicated to spying, harassing, and assaulting dissenters as well as liberal and radical organizations. But the group failed to designate Equi a major threat to American ideals. She dated her radical work to 1913, more than twenty years earlier, and she was one of two dozen Oregonians convicted under the Sedition Act. Few Portlanders had been arrested as often as Equi for her principled stands, and she wanted due recognition. The slight made her “absolutely livid with annoyance,” according to activist Julia Ruuttila. Equi telephoned the chief of police and threatened to sue the bureau unless the expose was revised with her name listed at the top as “Dr. Marie Equi, Queen of the Bolsheviks.” The title harkened to the time after the Russian Revolution when revolutionists and all other radicals were lumped together in America as Bolsheviks. She probably also recalled the opening lines of the song her friend Ruth Barnett penned about her: “Mary was the Queen of the Bolsheviks / Everywhere she went her name was known.” Nothing came of Equi’s insistence for top billing, but the experience revealed how much her reputation meant to her.2

Even in her later years Equi attracted seasoned labor leaders and younger progressives and radicals. Ruuttila recalled accompanying a number of them to Equi’s house in the evenings. Francis Murnane, president of the International Longshore and Warehouse Union, was a favorite. Once a Catholic seminarian, Murnane abandoned his thoughts of the priesthood after hearing a talk about the frameup of Tom Mooney. He considered becoming an attorney to defend those unjustly charged, but he undertook labor organizing instead. Others who trekked to see Equi were S. P. Stevens, fire union president, and John J. McNamara, charged with dynamiting the Los Angeles Times building during a bitter strike in 1910. Mary Equi recalled visits to her mother by Socialist and pacifist leader Norman Thomas and political activist and economist Scott Nearing.3

One of the new, younger leaders who sought Equi’s advice and support was Monroe Sweetland, a labor man and community organizer in his mid-twenties. Sweetland led the influential Oregon Commonwealth Federation (OCF), a progressive association of trade unions, unemployment councils, farmers, and students. The OCF was the kind of bold, inclusive operation that appealed to Equi, and she welcomed Sweetland’s visits. In 1937 she donated to the OCF campaign to oust Oregon’s Democratic governor, Charles Martin, an antilabor, anticommunist extremist who had launched a police squad of “Red-hunters” two years earlier throughout the state.4

Visitors to Equi’s house had to negotiate around a massive library desk and a heavily carved dining table with eight large chairs and a big buffet before finding a chair close to her bed where she sat poised for company. They often found her expansive and exuberant. According to Ruuttila, “She had a magnificent voice. Warm, deep, and eloquent. . . . She was fascinating to listen to—(but) you couldn’t get a word in edgewise.” Ruuttila knew by then that Equi took liberties with the facts for a good story, but she thought that made her more colorful. Besides, Ruuttila noted, “She was extremely honest in all ways that really mattered.” But Equi’s high spirits could be too much. “After two or three hours in her company,” Ruuttila recalled, “I used to feel emotionally exhausted, and so did the men I went there with.” Equi revealed to Hanna Sheehy-Skeffington one of the reasons for her high spirits, “As in all lung cases consumed with fever, I sparkle into life after 4 p.m. until 2 a.m.”5

In the latter part of her life Equi might have enjoyed her longtime bond with Charlotte Anita Whitney and she might have repaired her relationship with Elizabeth Gurley Flynn, but her strong dislike of communism distanced her from them. They both became leaders of the Communist Party USA. Whitney fell out of favor with Equi even further when it appeared that her onetime dear friend had taken advantage of an elderly sympathizer in order to inherit his estate. And she blamed her daughter’s decision to wed a Communist on five years of “bad influence” from Whitney and Flynn that caused her “grief and slow death.”6

No matter her Queen of the Bolsheviks claim, Equi was ever the political individualist. In 1939 she registered and presumably voted as a Republican rather than support FDR. As the troubles in Europe threatened to draw the United States into another world war, she apparently worried that the president would take the country to war as Wilson had done after she had voted for him.7

Equi strained to be positive about her daughter’s marriage, but she wrote to Sheehy-Skeffington, “Life deals us blows through our children.” She treated the couple kindly, but she remained “burned up with indigestion.” She was displeased and unhappy about the situation, but she did not sink into vindictiveness or spite. Instead, she joked about Tony Lukes, “I call myself his out-law.” She also helped the young couple by hiring a housekeeper for them.8

In time Equi’s disgruntlement softened, especially with the arrival of grandchildren. Mary had returned to her studies and graduated from Reed College, and the family relocated to a house a few blocks from Equi’s residence. Then, in the spring of 1938, Mary gave birth to her first child, Tony Jr. Six years later the Lukes celebrated the arrival of their second child, named Harriet Marie in honor of Mary’s two parents. Equi became an attentive grandmother who provided childcare and offered advice about childrearing. On one occasion, she sent a note to Mary, describing how she sang hymns and recited nursery rhymes to help little Harriet sleep. When Mary and Tony enrolled their children in Portland grade schools and later at Lincoln High School, Equi assisted with tuition.9

Years later Arthur Champlin Spencer, a childhood friend of Tony Jr., remembered how much he was in awe of Equi. “She was not like any little old grandmother. She was regal . . . quite imposing,” he said. “She sat bolt upright asking for her magazines and papers.” He also recalled how much Equi was interested in history and that she had begun research on her family’s genealogy.10

Equi employed nurses to visit or stay with her, but she had trouble keeping them, perhaps, as her daughter suggested, because she was too difficult to work for. Margaret D., the family friend, was an exception. Equi had delivered her as an infant, and she appreciated how much the older woman had encouraged her through nursing school. Margaret’s job was to visit Equi at night, help her prepare for bed, and then stay overnight in one of the rooms upstairs. But the visiting and talking usually extended for hours, and Equi often kept Margaret awake until 4 a.m. On one occasion, Equi showed her several trunks and boxes filled with newspaper clippings, letters, San Quentin mementos, and the awards she had received for her earthquake relief work.11

As the 1940s began, Equi was in her late sixties, and several of her loved ones passed away. Her sister Sophie died in Los Angeles in 1942, followed two years later by Dr. Belle Ferguson, whom she first met in The Dalles during her homestead days. Equi followed the career of Hanna Sheehy-Skeffington, who taught school during World War II, and then, in 1943, stood unsuccessfully as a candidate for the lower house of the Irish parliament. She died three years later. In Equi’s last known letter to her, she wrote, “I know now of no greater joy than in holding your hand and seeing you once again.” She closed, “Au revoir and goodbye.”12

Equi intermittently contacted other friends, and late one evening in 1943 she surprised Margaret Sanger with a telephone call. Sanger was discouraged that World War II distracted attention and funding from women’s health care, and Equi commiserated. Sanger persevered to see the American Medical Association endorse the addition of contraception in regular medical services and in medical education. In 1952 she helped establish the organization that became the International Planned Parenthood Federation. But not until 1963—forty-seven years after Equi and Sanger spent a night in jail together—did a Planned Parenthood clinic open in Portland.13

Few accounts remain of Equi’s final years of living alone, although Ruuttila described an occasion when Equi helped her. Ruutilla was fired from her newspaper position in 1948 for writing articles critical of Portland’s treatment of the six thousand African-Americans made homeless when the Columbia River broke through a railway landfill and flooded the vast public housing community in north Portland called Vanport. Through a mutual friend, Equi learned that Ruuttila was unable to pay her gas bills and struggled to live without heat and hot water, and she sent payment to settle all of Ruuttila’s accounts.14

In September 1950 Equi entered Good Samaritan Hospital in Portland after falling at home and fracturing her hip. She was seventy-eight years old, in frail condition, and she failed to improve. But she refused surgery and, therefore, never benefited from physical therapy. Ever the storyteller and charmer, she settled in with the hospital routine, entertained visitors, and became a favorite with the nurses. At one point, longshoremen remembered how she stood by them during the 1934 strike, and they sent a bouquet of thirteen red roses after hearing that she considered thirteen her lucky number. For the occasion, Julia Ruuttila wrote a poem for Equi that included the verse: “Fighter and friend to valiant end / Our champion to revere and defend.”15

After more than a year at the hospital, Good Samaritan transferred Equi in February 1952 to a nursing home located outside Portland. Around midnight on July 13, 1952, she died of renal disease at eighty years of age. A rosary for her was said two evenings later in downtown Portland. The next morning a cortege left the funeral home and proceeded to St. Michael the Archangel, the Catholic church of the Italian community, on Fourth Street, a few blocks from many of her street protests. The service was conducted amid the simple wood and plaster walls of St. Michael’s, a less grand space than the marble and granite of her family’s church in New Bedford, but it served an immigrant community of working people important to her. Although Equi objected to many Catholic tenets, she believed it was important to die “in the church,” she told a friend, because it offered “such wonderful hope.”16

Ralph Friedman, a prolific Oregon writer and folklorist, observed that Equi would have been honored with a political funeral if she had not outlived so many who would have attended. One of Equi’s friends suggested, “The problem with Doc is that she lived too long.”17

Equi’s entombment took place at Portland Memorial, a crematorium in southeast Portland. Today two vaults lay side by side and embedded in a brown-flecked marble wall. One is identified “Marie D. Equi, M.D. 1872–1952” and the other “Harriet F. Speckart 1883–1927.” Presumably, Mary Equi Lukes arranged for her parents’ remains to be placed together. After settling her mother’s estate, selling her house, and divorcing, Mary remarried and relocated with her husband and children to northern California.18

Portland’s newspapers eulogized Equi mostly for her combative spirit with nods to her medical work and her generosity to others. In the Oregonian she was “a firebrand in the causes of suffrage, labor, and peace.” Another article titled “Generous Dissenter” described her as someone who added “yeast to the dough of the solid citizens.” Equi’s hometown paper, the New Bedford Standard-Times, recognized her, as a prominent social worker rather than a physician, as well as a suffragist, and a member of one of the first Italian-American families in the city. The New York Times and other newspapers carried an edited version of the New Bedford notice.19

After Equi’s death, the Portland longshoremen’s union adopted a resolution acknowledging her as an “outstanding fighter” who “braved personal dangers and hardships to preserve peace, freedom of speech, and the right of labor to organize.” Former Oregon Governor Oswald West—the reluctant character witness at Equi’s sedition trial—remarked upon hearing of her death, “She was a radical, but she had a heart as big as a watermelon.”20 Julia Ruuttila, a fiercely committed Oregon labor activist herself, perhaps described her best. Equi was, she said, “a woman of passion and conviction (and) a real friend of the have-nots of this world.” She added, “I think she’s the most interesting woman that ever lived in this state, certainly the most fascinating, colorful and flamboyant.”21