CHAPTER 9

Military Ancestors: The British Army

At some point over the course of the last few centuries, one of your ancestors would have served in the British Army. There are plenty of clues that suggest this military link – an old photograph of a relative in army uniform; some medals passed down through the generations. This chapter shows you how to use these clues to access original records and piece together the army careers of your relatives, as well as gain a greater understanding of what life was like as a soldier.

A Brief History of the British Army

The beginnings of the modern-day British Army can be traced back to 1660 with the restoration of Charles II to the throne, for this was the first time a regular standing army was established. A small number of regiments were created on a permanent basis with the responsibility of guarding the King.

Nevertheless, there had been many wars and conflicts for centuries before 1660 and armies of men would have been raised as and when required, although on a temporary basis, being discharged when the fighting was over. Finding an ancestor who may have served in the army prior to 1660 is more difficult as there was no permanent institution and, therefore, there was no systematic record-keeping system.

‘There are many records available to help you trace your ancestor’s military career.’

The earliest method of raising a group of men to serve in a battle was tied into the feudal system, with the lord of the manor having the responsibility of gathering together such a body. Additionally, all men holding a certain amount of land were required to serve as knights, although the knight system was not used after the fourteenth century. Through the course of time the feudal system came to be replaced by the ‘contractual’ system, whereby contracts or indentures were used to secure military personnel. Indentures were used between the King and the nobility, and in turn by the nobility with the lesser sections of society right down to peasant level. The start of the English Civil War in 1642 saw the beginnings of a professional military body with the formation of the New Model Army in 1645 by Oliver Cromwell. The New Model Army was disbanded in 1660, shortly after the restoration of Charles II, and it is after 1660 that the origins of the modern British Army can be traced.

The regiments that formed the army in 1660 were recruited from units that were formed during, or even before, the Civil War. Two regiments of Horse Guards and two regiments of Foot Guards were created. Originally, these regiments served as the Army for England and Wales, with Scotland having its own forces. However, after the Act of Union between the two countries in 1707, these Scottish units were united with the English units to form the British Army.

The regiments formed in 1660 are the oldest in the British Army; thereafter the regiment became the basic unit that formed the core of the Army’s organizational structure. Army records were organized and retained on a regimental basis, and certain records may still be with the regimental record office. Indeed, it was only in 1920 that an army-wide service number was introduced for each serving soldier.

Each regiment would be under the overall command of a colonel. A regiment could be an infantry, cavalry, artillery or engineer regiment, with various specialist forces, such as the foot guards, also existing from time to time. Originally, regiments would be named after the colonels in charge of the regiment and, as such, the names would change with the change of the colonel. Hence, to make things easier to organize, a numbering system was also introduced in 1694, infantry regiments being named 1st Regiment of Foot, 2nd Regiment of Foot, etc. As the system of naming a regiment after a colonel became increasingly confusing (as more than one colonel could have the same surname) it was ordered in 1751 that regiments also take on official titles, such as the 4th Regiment of Foot being given the additional title of ‘King’s Own’.

Further changes were introduced in 1782, with regiments being attached to geographical parts of the country. Hence, the 5th Regiment of Foot became attached to Northumberland. This was done in part to increase recruitment, although regiments continued to recruit outside their given territories when required. The naming of regiments was changed once more in 1881. From that date, numbers were no longer used. Instead all regiments were given territorial titles, usually county names, although some continued to use their old number unofficially. This system of organization remained largely intact until and during the First World War. Service records for soldiers serving after 1922 have not yet been released to the general public, and changes occurring in army organization in the twentieth century do not require a detailed analysis for genealogical purposes.

The Organization and Hierarchy of the British Army

As mentioned, the basic army unit was the regiment. These regiments would be grouped into four general categories of troops:

1. Cavalry: These were the mounted horse regiments of troops. The majority were disbanded or merged in 1922, the horse being replaced by the tank.

2. Infantry: These were the basic foot soldiers who served on the line at times of conflict. Infantry regiments have traditionally formed the bulk of the army, and therefore this is where you are most likely to find your ancestor.

3. Artillery: Artillery regiments were specially trained to use cannon, mortars and other heavy guns.

4. Engineers: Their historical role includes survey work, mining, construction projects and support services to front-line troops.

Specialist regiments have also existed, such as the two foot guard regiments originally raised to guard the monarch in 1660, the Grenadier Guards and the Coldstream Guards. There are other non-regular army elements such as the Militia, and relevant records are discussed later in this chapter.

As regiments were subject to many name changes, mergers with other regiments, or even disbanding at various points in time, it is worthwhile checking the correct name for your ancestor’s regiment during the particular period of interest. You can do this online on the website www.regiments.org. Alternatively, consult the following comprehensive guide commonly found in archives and libraries, written by Arthur Swinson, called A Register of the Regiments and Corps of the British Army: the ancestry of the regiments and corps of the Regular Establishment.

Although the terms ‘regiment’ and ‘battalion’ are often used interchangeably, the difference in their meanings was fixed by 1660. Hereafter ‘regiment’ would be for the administrative organization, whereas ‘battalion’ was the term used for the actual fighting unit. Each battalion would be divided into ten units, known as companies. In theory each company would have 100 men, thus a battalion would comprise 1,000 men, but this was not always the case. An individual soldier (or ‘other rank’) would be recruited into any company of a particular battalion.

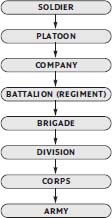

The diagram to the right shows how a battalion fitted into the wider hierarchy of the Army.

Army Ranks

To begin searching for your ancestor amongst the surviving records it is essential to know whether he was a commissioned officer or other rank, as the records have been organized according to this distinction (unless you are searching the period prior to 1660). A commissioned officer could be any of the following ranks: lieutenant, captain, major, colonel, brigadier or general. Your ancestor would have been an ‘other rank’ if he had held any of the following ranks: private, lance corporal, corporal, sergeant or sergeant major. Once you have this information you can begin the search for your ancestor’s records. The majority of these records are now stored at The National Archives (TNA).

Service Records Prior to 1660

As there was no regular army prior to 1660, there are no comprehensive service records. Additionally, what does survive contains little genealogical information.

The earliest lists of soldiers, recruited in the feudal period, may survive in TNA department series for Chancery or Exchequer records (specifically C 54, C 64, C 65 and E 101). In 1285 the Statute of Winchester required all males aged between 15 and 60 to equip themselves with armoury that they could afford and they would be duly assessed. By the fifteenth century such assessments were being made by the appropriate local official along with the Lord Lieutenant of the county (also known as Commissioners of the Array). The earliest such ‘muster lists’ survive from 1522; other miscellaneous lists would also have been forwarded to the Exchequer and Privy Council and form part of their records. A comprehensive guide to these records can by found in Tudor and Stuart Muster Rolls: A Directory of Holdings in the British Isles by J. Gibson and A. Dell (Federation of Family History Societies, 1991), including information on where they are held.

If your ancestor served during the English Civil War or Interregnum period after it, you may be able to find some evidence for this. Although there were no specific service records, there may be other records containing relevant information, mostly for officers only, though. The best place to start at The National Archives is to look through the Calendars of State Papers. Other published sources are also useful, such as:

• Edward Peacock’s Army Lists of the Roundheads and Cavaliers (listing all officers of both sides in 1642)

• W. H. Black (ed.), Docquets of Letters Patent 1642–6 (1837) (containing additional information on officers of the Royalist camp)

• P. R. Newman, ‘The Royalist Officer Corps, 1642–1660’, Historical Journal, 26 (1983) (ditto)

• R. R. Temple, ‘The Original Officer List of the New Model Army’, Bulletin of the Institute of Historical Research (contains relevant sources for the New Model Army)

• I. Gentles, The New Model Army (a history of the New Model Army)

You may find further information in The National Archives State Papers, series SP 28 (the relevant lists have not been calendared) or the Exchequer series.

Individual Army Records Post 1660

Individual army records since 1660 have been organized into those of officers and other ranks, and finding records for each group will be discussed separately. Another important defining moment for the family historian is the onset of the First World War, as records for officers and soldiers serving before this conflict are stored in a different place to those serving after it.

Broadly speaking, most people search in two types of records: service records and pension records.

‘There are two main types of records: service and pension records.’

Officer Records 1660–1913

The officer classes came almost exclusively from the more privileged sections of society for this period, the majority also having rural gentry backgrounds. Indeed, it was a fundamental prerequisite to be a gentleman before an individual was even considered for an army commission. Until 1871, the way most people became army officers was through the purchase of their commission. Nor was promotion based on any meritocracy; promotions were also bought, officers seldom being promoted through ability. It would not be unusual for wealthy young boys (there was no minimum joining age) to have rapid promotions at the expense of more talented, if less wealthy, officers. The problems of this state of affairs became apparent in the Crimean War (1853–56), and by 1871 it was no longer possible to purchase commissions.

Army Lists

As the Army did not have a central record-keeping system until the First World War, the surviving records come from documents created by the relevant regiment. The majority of the records are now at The National Archives, but you may also find additional information at the regimental museum and it is worthwhile contacting these institutes too. Perhaps the best place to begin searching for an officer is by using the Army Lists.

USEFUL INFO

Other Published Sources

• Promotions of individual officers were often announced in the London Gazette (available online at www.londongazette.co.uk, or at The National Archives, series WO 121).

• The Times would also publish promotions of officers. It is also useful for providing service histories in obituaries of some officers, or reporting various conflicts. The newspaper’s archive can be searched online at most libraries.

• The Dictionary of National Biography and other substantial biographical dictionaries will also have entries for distinguished officers and should be consulted. You may also find details for your officer in regimental histories. The National Archives has some published books giving biographical details for officers serving in the early eighteenth century and before. These can be found in its library.

Army Lists were begun in 1702 and listed every officer serving in the Army. After 1740 it became routine to publish these annually (in times of conflict they may have been published more frequently than this). If you know the approximate date your ancestor served in the Army you can trace his entire career, from initial commission to subsequent promotions and eventual retirement, including details of which regiment he belonged to. The lists are somewhat basic, however, and do not expect to find any extensive career details or any genealogical information.

You can find Army Lists in various institutes. A full set from 1759 is in The National Archives. Additionally, the original manuscripts of the Army Lists from 1702 to 1752 can be located in TNA series WO 64. The British Library also has a complete set from 1754. The National Army Museum, the Imperial War Museum, regimental museums and other large reference libraries also have collections, although not always complete collections.

Another unofficial publication, Hart’s Army Lists, should also be consulted if your ancestor’s army service fell in the relevant time period. Hart’s lists cover the years 1839 to 1915 and give more details than are found in the Army Lists, including short biographies of the officers and career details. Hart’s Army Lists were published on a quarterly basis and cover the regular British Army and officers of the British Army in India. An incomplete set of Hart’s Army Lists is located at The National Archives on open shelves. The complete collection can be found in series WO 211, along with the working notes Hart used to compile his lists for 1839 to 1873.

Service Records of Officers

As there was no army-wide service record-keeping system until 1914, service records will be found in many different record series. There is no one single document providing the entire service career for an individual. Instead records were kept separately, by both the regiment and the War Office, although the War Office did not start collecting this information until the early nineteenth century. Both these sets of records are now held at The National Archives in series WO 25 (for War Office records) and WO 76 (regimental records). Additionally, there is an incomplete name index to these collections (also at The National Archives). As it is incomplete, searches should still be made in both series, even if the name of your ancestor does not appear in the index.

War Office Records in WO 25

As stated, the War Office records do not contain complete service histories for every officer in the British Army. Rather, they comprise an assessment of officers at various points in the nineteenth century. Five surveys were taken at different dates during the century, officers being required to send returns on their statements of service at that point in time. As the officers themselves were responsible for giving this information, there are gaps in the data as not every officer completed the returns in full. Each survey can now be found in WO 25 and some surveys contain more information then others. The details for each survey are listed here.

The survey is arranged alphabetically and contains only details of service history.

2.

1828 (WO 25/749–779)

This survey is more detailed and contains information about service completed before 1828. It is arranged alphabetically and military history is provided along with dates of commission. Further information relating to marriage dates and birth dates of children is also included.

3.

1829 (WO 25/780–805)

Organized on a regimental basis, this survey only refers to officers active at the time. It provides the same information found in the second series. In addition the wives of soldiers are indexed separately; their maiden names are provided along with their date and place of birth and, occasionally, their date of death.

4.

1847 (WO 25/808–823)

The survey is arranged alphabetically and contains information very similar to that found in the second survey.

5.

1870–72 (WO 25/824–870)

The survey covers some returns outside those dates and is arranged by the year the returns were compiled and thereafter by regiment.

If your ancestor was an officer in the Royal Engineers, their service records can be located in WO 25/3913–3919, covering the years 1796 to 1922.

Regimental Records WO 76

This series contains the records made by individual regiments which were subsequently transferred to the War Office. As such they are organized on a regimental basis and the entire series covers the years 1764 through to 1913. Of course there will not be information for every regiment from 1764 and the level of information for each regiment also varies, although generally more detailed records were kept through the course of the nineteenth century. To begin searching these records refer to the name index (mentioned above). However, if the name is not found, it is advisable to search anyway. Identify where the records for your ancestor’s regiment are within the series and search through.

There are certain regiments that do not have their records within either WO 76 or WO 25, but in other series. Below is a list of such regiments:

• Royal Garrison Regiment Officer service records (1901–05 only): WO 19

• Gloucester Regiment service records (1792–1866): WO 67/24–27

• Royal Artillery officer lists (1727–51): WO 54/684, 701

A pay list of officers (from 1803 to 1871) can also be found in WO 54/946.

Records for Granting of Commissions

Apart from the service records themselves, documents relating to the granting of commissions can provide additional information. The purchase of commissions was instituted in the reign of Charles II and was not abolished till 1871. It was possible to buy a commission up to the rank of colonel, although the Commander-in-Chief could award free commissions. An officer was awarded their rank by these royal commissions and the date of these commissions can be located in numerous published sources (the Army List, the London Gazette, The Times, etc).

Perhaps the most interesting documents regarding the granting of commissions are the actual applications for purchasing or selling such commissions. These are also held at The National Archives, in series WO 31, and cover the years 1793 to 1870. The applications contain a lot of personal information, such as baptismal dates. They often have letters of recommendation attached, which can give further details about the character of the candidate and information about his life (such as education and employment details) and his parentage.

Other records of relevance concerning the system of commissioning officers include:

• Warrants issuing commissions from 1679 to 1782, in SP 44/164–418. After 1855 they can be found in HO 51.

• The awarding of commissions was recorded in commission books by the Secretary of State for War. The books cover the years 1660 to 1803 and can be found in WO 25/1–121.

• Succession books recorded the promotions and transfers of officers. They are organized by regiment and date. The regimental records can be found in WO 25/209–220 for 1754–1808, and another set of records in WO 25/221–229 for 1773–1807.

The Royal Artillery and Royal Engineers regiments have their commission records in series WO 54, for the years 1740–1855.

Half-pay Records

As pensions were not introduced until 1871 a system of half-pay was used instead. Begun in 1641 to compensate officers in reduced or disbanded regiments, it soon became a method of retaining officers as they still held on to their commissions whilst on half pay. Officers on half pay can be found in the Army List. There are also original records in WO 23, although little genealogical information is provided in this series.

The series PMG 4 is more genealogically relevant, the ledgers recording payments of half pay from 1737 to 1921. The series is alphabetically indexed after 1841 and it is possible to find the date of death and, after 1837, addresses of the recipients. The more modern ledgers also give date of birth details.

Further Records Providing Personal Information

In order to join any government service an individual had to provide birth or baptismal details. Hence, collections of these baptismal records have survived in the following series (which both have indexes):

• WO 32/8903–8920: 1777 to 1868

• WO 42: 1755 to 1908. This series also includes marriage, death or burial and birth/baptismal certificates for children

Widows’ pension records may also be useful. Widows were entitled to pensions far earlier than retired officers, in 1708.

• WO 25/3995 and 3069–3072 are registers for bounty paid to widows between 1755 and 1856. It is fully indexed

• WO 25 has numerous pieces relating to applications for pensions and may include details of remarriage. You will also find further information in PMG 10 and PMG 11

‘To join a government service a person had to give birth or baptismal details.’

Lastly, it may be worthwhile searching the records for pensions paid to children and other dependent relatives. Such pensions were introduced from 1720, and were paid out of the Compassionate Fund and the Royal Bounty. Registers recording who received this money and the amount they were paid, from 1779 to 1894, can be found in WO 24/771–803 and WO 23/114–123. Further ledgers can also be viewed in PMG 10 for 1840 to 1916.

Records for Other Ranks

The majority of the British Army was composed of non-commissioned officers (sergeant major, colour sergeant, sergeant, corporal, lance corporal) and rank-and-file soldiers – privates – who were collectively known as ‘other ranks’. Before 1806, enlistment was for life; from 1807, discharge was permitted after 21 years’ service, and after 1817 soldiers could seek an early discharge after 14 years. Rates of pension were calculated according to length of service, and are discussed later. For most periods in history these men were recruited voluntarily, with conscription being used only on a few occasions. These men usually came from the poorest sections of society, often being labourers endeavouring to escape poverty, even though the pay was very little. Additionally, a disproportionate number were recruited from Scotland and Ireland.

Employment conditions for the other ranks were far from ideal. The majority of the barracks, which housed the soldiers, were cramped and often had poor sanitary conditions. The quality and quantity of food was also inadequate, although rations for beer were generous, leading to the reputation of drunkenness of many of the soldiers. Not every soldier was automatically entitled to marry, and housing for spouses was also limited. These poor conditions were addressed following the failures of the Crimean War in the 1850s. Reforms were introduced in the 1870s in order to improve the living conditions of the soldiers, hoping that this would in turn improve their fighting ability.

Service Records

The National Archives holds the vast majority of service records for other ranks, found in a variety of places.

Soldiers’ Documents, 1760–1913

If your ancestor was a soldier during this period, the easiest place to begin searching for any surviving documentation is within the ‘soldiers’ documents’ series of WO 97. Although they are often referred to as ‘service records’ the documents were compiled for pension purposes and are not actual service records. They were created when a soldier was discharged and awarded a pension by the Royal Hospital at Chelsea. The Royal Hospital was created in 1682 to house soldiers who had been injured whilst on active service. Pensioners were termed either ‘in-house’ or ‘out-house’ pensioners, depending on whether they took up residence at the Hospital or received a pension at their private residence. Most surviving individual soldiers’ documents were created in the administration of this pension rather than as specific service records. As such the records are not complete for every serving soldier but, until 1883, only for those discharged to pension. Nor will there be any record for any soldier dying on active service. Additionally, soldiers who were discharged from the Army by purchasing their way out of their remaining period of service would not be included. From 1883 to 1913 the series is fuller and most soldiers should be within these records.

If you do find your ancestor’s record amongst the series, there is usually a good amount of detail to be gleaned from it. Most documents include:

• Full name

• Age and place of birth

• Physical description

• Trade or occupation before joining the Army

• Details of next of kin after 1883

The series have been compiled using the following documents, although not every document would have survived for each soldier:

• Discharge forms issued on the day the soldier was discharged from the Army

• Attestation forms, compiled the day the soldier officially enlisted into the Army

• Proceedings of the regimental board, including a record of service, detailing the service career of the soldier

• Any supporting documentation relating to discharge

• Past service questionnaires if other documentation for the soldier’s service did not survive

• Affidavits to declare that the soldier was not receiving funds from any other public body

Records for the early period are less complete, but should contain discharge papers at least. The more modern documents usually contain at least the discharge form and attestation papers.

The actual documents themselves are arranged differently according to different time periods. The dates refer to date of discharge not date of attestation. The series is broken down as below:

• 1760–1854: WO 97/1–1271 The records are arranged on a regimental basis, and then alphabetically by the surname of the soldier. This set of records has been fully transcribed by name and it is possible to do a simple name search in The National Archives online catalogue.

• 1855–72: WO 97/1272–1721 These are organized on a similar basis to the collection above, by regiment then surname. However, there is no online index to date and it is only feasible to search within the records if the regiment is known.

• 1873–82: WO 97/1722–2171 The records for soldiers are organized into cavalry, artillery, infantry and miscellaneous troops and then by surname.

• 1883–1900: WO 97/2172–4231 The documents are arranged by surname only.

• 1901–13: WO 97/4232–6322 As above, a simple surname arrangement.

Other Records at The National Archives

If you are still unable to find a record relating to your ancestor, even though you suspect he was awarded a pension, there are other options worth trying:

• WO 121: 1787–1813 A similar collection to WO 97, containing papers for those discharged and awarded a Chelsea out-pension. This series can also be searched by name online in The National Archives catalogue.

Records from WO 121/239–257 relate to soldiers discharged without pension from 1884 to 1887.

• WO 400: 1799–1920 These contain the soldiers’ documents for the Household Cavalry.

• WO 116: 1715–1913 The series contains pension books for those discharged due to medical reasons or disability.

• WO 117: 1823–1913 Similar to WO 116 but this series contains pension books for those discharged after completing a period of ‘long service’.

• WO 120: 1715–1857 A series of the Chelsea regimental registers of pensioners. These mainly concern soldiers already in receipt of pension who may be required to serve again.

• WO 69: 1803–63 This series contains service records for soldiers of the Royal Horse Artillery. They are arranged by service number, which can be ascertained from the indexes found in WO 69/779–782, 801–839.

• Kilmainham Hospital pension registers This hospital was the forerunner to the Chelsea Hospital, being opened in 1679 just outside Dublin to administer pensions to Irish soldiers. The records for this hospital are kept separately in WO 118 (1704–1922) and WO 119 (1783–1822). The records are arranged by date of admission to pension.

There are also two series for mis-filed documents and they should be checked if you are unable to find any record in the main series. They are also organized by discharge date, by surname only:

• 1843–99: WO 97/6355–6383

• 1900–1913: WO 97/6323–6354

Other Relevant Records for Soldiers

The War Office created other sets of records apart from pension records that can also be used to trace a soldier. These can be useful as you may be able to find a soldier regardless of whether or not he received a pension.

Description Books

As suggested by the title, these books give the physical attributes of the soldier concerned. They also provide details as to his age, parish of birth and occupation. They form two main series:

• WO 25/266–688 (1778–1878) These are the description books for the regiments, with the majority only surviving for the early nineteenth century.

• WO 67 (1768–1913) This series is for the regimental depot description books. However, books only survive for a few regiments (as detailed in the online catalogue).

Pay Lists and Muster Rolls

This is the main set of records to search for your ancestor if you are unable to find any service history. Each regiment compiled on a monthly or quarterly basis the names of each and every serving officer and soldier in that month or quarter and where they were stationed at that particular time. Additionally, they list when a soldier first enlisted and when he was discharged. They may also contain birthplace details of soldiers. From 1868 to 1883 the Musters would also have a marriage roll listing wives and children of serving soldiers. It is therefore possible to trace the career of any individual soldier, his start date, any promotions, where he served and his final discharge date. However, this can only be done if you know the regiment your ancestor served in and an approximate time period.

The first muster rolls and pay lists date from approximately 1730, although not every regiment kept a muster this far back. They are in a number of series arranged by regiment and chronologically:

• WO 12: 1732–1878 This is the main series containing Musters for most regiments.

• WO 10, WO 69, WO 54: 1708–1878 These series contain the Musters for the Royal Artillery.

• WO 11, WO 54: 1816–78 The Musters are separate for Royal Corps of Sappers and Miners until their merger in 1856.

• WO 13, WO 68: 1780–1878 This series includes Musters for Militia and Volunteer forces.

• WO 16: 1878–98 After 1878 the majority of Musters can be found in this series. Bear in mind that the Army was reorganized (thanks to the Cardwell Reforms) in 1881, when many regiments changed names or were amalgamated. Your ancestor’s regiment may be known under a different name after 1881 and would have been filed under that name (this can be researched using the Army Lists). The last records are for 1898 as the War Office did not keep Musters after that time.

Army Records for the First World War

The start of the First World War had a large impact on the organization of the Army. It involved an enormous increase in numbers serving for both officer and other ranks, and almost every resident of the country was involved, in either a civilian or a military capacity. The demand for manpower was such that conscription had to be introduced in March 1916, after the early enthusiasm for volunteering gave way to the reality of the horrors of modern warfare. In total approximately 7 million soldiers served in the British Army during the conflict and approximately half of these numbers were conscripts. Most men served until 1919, as the armistice of 11 November 1918 was originally a truce and not an official end to the conflict. Hence soldiers did not begin to be discharged until 1919, when it was guaranteed that there would not be a resumption of hostilities.

Unfortunately, there is no certainty that you will find the service record for your ancestor. A large proportion of service records were destroyed during bombing by the Germans in 1940, during the Second World War. The survival rate depends on whether you are searching for an officer’s service record or that of an other rank. It is estimated that approximately 65 per cent of records for the latter were destroyed in the bombing. Additionally, some of the documentation that does survive has been subjected to fire and water damage and may be difficult to read. This will be described in more detail below.

‘You can trace individual officers through the Army Lists.’

Officer Service Records

During the start of the conflict officers still came from the privileged and gentlemen classes. However, as the war progressed, the large numbers of casualties led to a shortfall in the numbers of officers. Thus promotion from the other ranks became more commonplace and members of the lower middle classes and even some working-class men joined the officer classes.

The surviving records for officers serving in this period are at The National Archives. Of course it is still possible to trace individual officers through the Army Lists, although for security reasons the Lists were less detailed than in peacetime. Additionally, the rapid promotions given to some soldiers would not always be recorded in the Army Lists. Unfortunately, the main service records were also destroyed by bombing in 1940 and only the supplementary series is now available. The supplementary series was made up from the ‘correspondence’ file, which each officer had in addition to their service record. These files vary in length depending upon the length of service for each officer. In total The National Archives holds over 217,000 records and the majority can be found in two separate series:

• WO 339 This series is for officers who were serving in the Regular Army prior to the onset of the conflict. It also contains the files for those who were given a temporary commission during the war, along with those commissioned into the Special Reserve of officers. As such it contains the majority of records, approximately 140,000 officer files.

• WO 374 The smaller of the two series, it contains files for those commissioned into the Territorial Army and contains approximately 77,000 individual files.

A far smaller series, WO 138, holds the files of the most famous and notable officers of the First World War, such as Prince George, Duke of Cambridge, and the famous poet Wilfred Owen.

These series have been indexed and can be searched online in The National Archives catalogue. However, the indexes only give the surname, first initial and rank and, unless the surname is very uncommon, you are likely to have numerous entries for the surname. Hence, you will have to use WO 338 to identify the correct entry. WO 338 is an index to the records held in WO 339, but is not available online and will have to be consulted onsite.

Service Records for Other Ranks

Service records for other ranks are also to be found in two series held at The National Archives:

• WO 363 This is the main series of records. The records were the ones that were subject to enemy bombing in 1940 and, therefore, are sometimes referred to as the ‘burnt documents’. They originally contained records for all soldiers who served between 1914 and 1920 and were either killed in action or were demobilized after the end of the conflict. Due to the bombing in 1940 only a small percentage of the original records survive (approximately 20–25 per cent in total). The amount of damage done to each file varies, some pages being only slightly affected whereas other pages are almost illegible.

• WO 364 These records are known as the ‘unburnt documents’ and represent a sample of pension records awarded to soldiers after discharge (either for length of service for those soldiers signing up before 1914, or for those injured during the conflict and awarded a disability pension). They represent only about a 10 per cent sample of all such awards, and consequently the collection is significantly smaller than WO 363.

• WO 400 The series for service records for the Household Cavalry including for the First World War. Service records for Foot Guards are also amongst this series but are not currently at The National Archives.

The length of each individual service file varies considerably depending on how much they were damaged or the amount of correspondence each file generated. WO 363 and WO 364 have been microfilmed and it is not possible to view the original records. Each series is arranged in strict alphabetical order and not by regiment. However, depending on how much information you know about the soldier you are interested in, you may need the service number and regiment to identify the correct file. These can be found using the Medal Index Cards (see below). Additionally, to find out the activities of the regiment during the conflict you will need to consult the relevant war diary (see below).

CASE STUDY

Ian Hislop

Ian Hislop’s family is steeped in military history, and he has always taken a keen interest in the subject, ever since he produced a project at school on the Boer War.

Both Ian’s grandfathers served in the First World War. Having asked around the family, Ian discovered that his paternal grandfather, David Murdoch Hislop, served in the 9th Battalion, Highland Light Infantry, and was posted to the front line in 1918. On 29 September he saw action at the battle of Targelle Ravine, with many of his fellow soldiers losing their lives as his regiment suffered heavy losses on one single morning of fighting. After two weeks they finally broke through the German front line, hastening the enemy retreat which finally brought about the Armstice on 11 November. Ian was able to follow in his grandfather’s footsteps by locating the unit war diary for the regiment at the National Archives in record series WO 95, and then looking at trench maps in series WO 297 that showed precisely where they were stationed on given days of the campaign. Sadly, though, David Hislop’s service record did not survive.

Of perhaps greater interest was Ian’s maternal grandfather, William Beddows, an army sergeant during the First World War who, being in his forties, trained new recruits for front-line action rather than serve himself. Nevertheless, he had a distinguished career and saw plenty of action. Beddows enlisted into the army in 1895, and within a few years was caught up in the Boer War, fighting five major campaigns including the notorious battle of Spion Kop, when 1,300 British soldiers were killed advancing towards Boer positions under heavy shell-fire. Much of this information was known to Ian’s mother, but Ian was able to research in more detail about the campaign. Although Beddows did not keep a diary, records from other soldiers, located at institutions such as the Imperial War Museum and National Army Museum, reveal in vivid detail the horror of the battle, when Beddows and his comrades were forced to use the bodies of their fallen friends as shelter from the Boer snipers.

Yet the strangest coincidence lay within his paternal family tree. Further genealogical research linked Ian with a distant relative named Murdoch Matheson, who was born on the island of Uig. Some of his medals were found within Ian’s family, which gave crucial information about his regiment and some of the campaigns he served in from the clasps. On checking The National Archives online catalogue, his military service record was located. This confirmed that he enlisted in the 78th Foot Regiment in 1794; in turn, this information led to an examination of Muster Lists in record series WO 12, which revealed that Matheson also travelled to South Africa, landing at Cape Town nearly a century before Ian’s grandfather went there to fight the Boers. The same Muster Lists and associated pay books proved that as part of a long career in the army Matheson travelled the world before coming back to Uig to settle down and raise a family. His discharge to pension survives in series WO 97, where his discharge papers reveal that he finally left the army in 1813 when he was 45 years of age – important biographical information to enable a search for parish records and other family material in Scotland.

The website www.ancestry.co.uk is placing the entire collection of WO 364 online, which subscribers to the site will be available to search.

Medal Rolls

Many people researching their ancestors’ service records may have a medal from that conflict. Indeed every soldier of the First World War serving overseas was awarded two campaign medals – the British War Medal and the Victory Medal. Additional medals were given to individuals who served on particular fronts at particular times, such as the 1914 Star, or who sustained injuries through the conflict, such as the Silver War Badge.

The awards of these medals were recorded in a medal roll and an index card was also created to find a soldier’s entry in the appropriate medal roll. These records form the closest surviving documentation for an Army Roll indexing every individual. The Medal Index Cards have been digitized and copies of these images are available on The National Archives website on Documents Online. It is possible to search the Index free of charge, although downloading an image will incur a charge. Often this is the only record that survives for a serving soldier, and the Index Cards can be used to ascertain the regiment and service number of your ancestor. Basic details relating to the soldier’s period of service are also given, such as date of enlistment and discharge along with field of conflict. Separate medals, known as gallantry medals, were also issued to individuals who were rewarded for individual acts of heroism. These were indexed by separate cards, also available to search on Documents Online. Medal rolls for earlier conflicts can be found at The National Archives. There are research guides available online at www.nationalarchives.gov.uk to help you find the relevant record series.

1.

Commonwealth War Graves Commission

This commission was created in order to remember the war dead of the First World War (and later wars). The commission has placed the Debt of Honour Register online on www.cwgc.org. This register lists all casualties along with when they died and where they were buried. Sometimes you may also find information about relatives. This register can be searched free of cost.

2.

War Diaries

These diaries are useful for those interested in the operational history of the First World War. Each battalion recorded their movements, activities and fighting on a daily basis. However, they are not personal recollections of individuals fighting in the war; these recollections are now at the Imperial War Museum. The war diaries can be found at The National Archives in series WO 95. Some have been digitized and placed online at Documents Online, others are on microfilm and some are still in original paper form. Some copies can also be found at the appropriate regimental museum, although they will be the same copies as found at The National Archives.

3.

Pension Records

The National Archives has various series of pension records. The main series is to be found in PIN 26, although only a 2 per cent sample now survives. The files relate to personnel applying for pensions even if they were not awarded one. It has been indexed by name on the catalogue and can be searched by name.

4.

Personal War Diaries

Although the majority of Army records are held at The National Archives, you can also find certain useful information at the Imperial War Museum. The Museum holds a ‘documents collection’ containing private papers and journals of serving officers and soldiers in the First World War (and other conflicts). It also has a number of records for war poets along with numerous other personal archives. Further information can be found on their website, at www.iwm.org.uk/collections/search.

Service Records Post First World War

Surviving service records are only in the public domain for those men who were discharged shortly after the end of the First World War in 1918. If the individual served into the 1920s his service record is still retained by the Ministry of Defence. The dates the records are retained from vary depending on whether your ancestor was an officer or an other rank. If an officer served after 31 March 1922 his records will still be retained, and the same for soldiers serving after the end of 1920. Next of kin can apply to the Ministry of Defence directly at the following address:

Ministry of Defence’s Army Personnel Centre

Historic Disclosures

Mailpoint 555

Kentigern House

65 Brown Street

Glasgow G2 8EX

The British Indian Army

All of the above information has related to the regular British Army. However, the British also had a military force specifically for maintaining British rule in India, and there are separate archives relating to this force. The British Indian Army had officers of European origin and was under the control of the Viceroy. It was formed in 1859 after the Indian Rebellion of 1857, a successor to the army maintained by the East India Company (EIC). The trading company maintained forces in three regions in India (Bengal, Madras and Bombay) from the mid-eighteenth century onwards. These armies were known as ‘Presidency Armies’. Each regiment of these three armies had European officers; however, they had other ranks of European or ‘Native’ origin. After the failed Rebellion of 1857, the East India Company was abolished and India was governed directly by the British Crown. Henceforth, European officers staffed the Bengal, Madras and Bombay armies until these sub-armies were united into one Indian Army in 1889. Additionally, the other ranks would solely be of Indian origin.

The British Library now holds the majority of records relating to the British colonization of India, including military records. They form part of the Library’s Asia, Pacific and African collection.

British Indian Army Officer Records

As with the regular British Army, the best place to begin tracing the career of an officer of the Indian Army is through the Indian Army Lists. They were published from 1759 for the Bombay and Madras Presidencies and 1781 for Bengal. In 1889 a universal India Army List was published due to the amalgamation of all three forces. The British Library has the complete collection, and an incomplete collection can also be found at The National Archives.

Individual service records were only kept from 1900 onwards until 1950. They are held in the British Library in series IOL L/MIL/14 although they are subject to 75-year closure rules (from the date the individual entered the Army). Further information can be found in the information leaflets on the website of the British Library.

Other Rank Records

The British Library also has recruitment records, muster lists and other registers for European men serving as soldiers within the Indian forces. More information can be found in the appropriate information leaflet in the British Library. The National Archives also has certain lists and registers originally created by the East India Company.

USEFUL INFO

Suggestions for further reading:

• The National Archives has produced a number of useful research guides to all aspects of its records for the British Army, which can be found on its website

• The British Library has similar information for its collection of Indian Army military records

• Tracing Your Army Ancestors by Simon Fowler (September 2006)

• Army Service Records of the First World War by William Spencer (August 2001)

Militia Records

The militia was a group of locally raised volunteer armed forces and can be traced back to Anglo-Saxon times. Records for such units survive from the Tudor period until the end of the Civil War; militia units were next raised in 1757 and continued to exist until 1907 with the passing of the Territorial and Reserve Forces Act, which formed the Territorial Force (which became known as the Territorial Army in 1921). The majority of surviving material concerning the militia can be found at The National Archives or local record offices.

Tudor and Stuart Militia Records

Militia units had been raised for local defence for centuries. The practice was codified in 1285 when the Statute of Winchester was passed and all males aged between 15 and 60 were expected to arm themselves in case they were called for service in the militia. Local Commissioners of Array or the Lord Lieutenants of the county were given the responsibility in the sixteenth century of ensuring these groups were raised adequately and it is their muster records that form the present-day archive for militia units during the Tudor and Stuart periods. These local authorities would forward their muster rolls to the Exchequer or the Privy Council and most of these rolls can be found at The National Archives.

The muster rolls are organized by county, hundred and then parish. The rolls list all male residents who were eligible to be called to arms if required. The earliest known rolls survive from 1522 and the amount of information given on a roll would vary. Some may provide individual ages, occupations and/or income (as individual wealth would determine what arms the men would be expected to provide). Other rolls may be comparatively brief and simply list the total number of eligible men in the parish. As mentioned, the majority of these rolls are at the National Archives (in the Exchequer series and the State Paper series), although some may also be found at local record offices and at The British Library. The easiest method of locating which muster rolls survive for a particular locality and where they are kept is by referring to Gibson and Dell’s Tudor and Stuart Muster Rolls – A Directory of Holdings in the British Isles (Federation of Family History Societies, 1991).

Militia Records 1757–1914

In 1757 the Militia Act reintroduced militia regiments into each county of England and Wales. These regiments would serve only in Britain and Ireland and not abroad. Each parish had to provide a number of suitable males to serve but, as there were too few volunteers, a form of conscription was introduced. However, this system proved very unpopular and was abolished in 1831, with militia units continuing with volunteers thereafter.

Militia Lists 1757–1831

The surviving records of this conscription process are of great genealogical relevance as local Justices of the Peace or county Lord Lieutenants had to provide annual lists of all men aged between 18 and 45 and a separate list of those chosen to serve. These lists are to be found in local archives and some may give details of each man, his occupation and age and his marital status (and sometimes children too) for each parish. Unfortunately, lists of every parish have not survived. It is best to consult Gibson and Medlycott’s Militia Lists and Musters, 1757–1876 (Federation of Family History Societies, 2000) to ascertain what has survived for each locality.

Records at The National Archives

The National Archives hold the main service records of men who served under the various militia forces from 1769 onwards. The militia was organized on a similar basis to the regular Army, with officers and other ranks.

• Militia officer records: Service records for militia officers can be found in the regular Army officer records in series WO 25 and WO 76. Additionally, WO 68 has the records of militia regiments including returns of officers’ services. Commissions can be found in HO 50 (1782–1840) and HO 51 (1758–1855). Relevant published sources include Officers of the Several Regiments and Corps of the Militia and the Militia Lists. The London Gazette also published details of appointments for militia officers.

• Other rank records: Relevant records for other ranks can be found in the following National Archives series:

![]()

Attestation papers can be found in WO 96 (1806–1915). These records provide a service record of each individual and may also give birth details. The papers are arranged by the regular army regiment the militia regiment was attached to, and then alphabetically. WO 97/1091–1112 contains the attestation papers of local militia regiments for the years 1769 to 1854. These have been catalogued by individual name and it is possible to search by name online in The National Archives catalogue.

Attestation papers can be found in WO 96 (1806–1915). These records provide a service record of each individual and may also give birth details. The papers are arranged by the regular army regiment the militia regiment was attached to, and then alphabetically. WO 97/1091–1112 contains the attestation papers of local militia regiments for the years 1769 to 1854. These have been catalogued by individual name and it is possible to search by name online in The National Archives catalogue.

![]()

The main series of records for the militia can be found in WO 68. This series (along with officer records) includes enrolment lists, description books and casualty details. The casualty records may also give details of marriages and children.

The main series of records for the militia can be found in WO 68. This series (along with officer records) includes enrolment lists, description books and casualty details. The casualty records may also give details of marriages and children.

![]()

Muster and pay lists for the militia can be found in WO 13 (1780–1878).

Muster and pay lists for the militia can be found in WO 13 (1780–1878).

![]()

Records of militia men who were entitled to pensions can be found in the registers in WO 23 (1821–29). Admissions into Chelsea Hospital are located in WO 116 and WO 117.

Records of militia men who were entitled to pensions can be found in the registers in WO 23 (1821–29). Admissions into Chelsea Hospital are located in WO 116 and WO 117.

![]()

Militia men did not generally receive campaign medals but were awarded the Militia Long Service and Good Conduct Medal. The medal roll can be located in WO 102/22.

Militia men did not generally receive campaign medals but were awarded the Militia Long Service and Good Conduct Medal. The medal roll can be located in WO 102/22.

‘Militia lists may give details of occupation, age, marital status and children.’

Volunteer Organizations

Along with information on earlier militia records, information on other volunteer units – and the records that survive for them at The National Archives – can be found in W. Spencer’s Records of the Militia and Volunteer Forces 1757–1945 (Public Records Office, 1997). Volunteer organizations include:

• Volunteers – raised in 1794, these were separate to the organized militia units but were disbanded in 1816, only to be revived in 1859 as the Volunteer Force. The cavalry equivalents of the Volunteers were the yeomanry and imperial yeomanry. Most of the relevant documentation, including musters, pay lists and officers’ commissions are held at The National Archives, and are summarized in a research guide online at www.nationalarchives.gov.uk.

• Territorial Force – formed in 1907 when the Volunteer Force was merged with the Yeomanry, with the Territorial Army created in 1921. Documentation is held in relevant regimental museums, although officers’ service records during the First World War will be held at The National Archives in series WO 374 (see above).

• Home Guard (Local Defence Volunteers) – service records are closed to the public for 75 years, and can only be obtained by those who served, or their next of kin, by writing to the Army Personnel Centre, Glasgow. There are some records at The National Archives, such as copies of the Home Guard Lists, histories of some regiments in series WO 199 and unit war diaries for the Second World War in WO 166, which provide details of operations and movements.

USEFUL INFO

Suggestions for further reading:

• Tudor and Stuart Muster Rolls – A Directory of Holdings in the British Isles by J. Gibson and A. Dell (Federation of Family History Societies, 1991)

• Records of the Militia and Volunteer Forces 1757–1945 by W. Spencer (Public Record Office, 1997)

• Militia Lists and Musters, 1757–1876 by J. S. Gibson and Medlycott (Federation of Family History Societies, 2000)

Tracing a Campaign

Battalion War Diaries

For researchers interested in discovering more about the military history of the First and Second World Wars, and the part each unit played in fighting, the best place to turn to is the war diaries (mentioned above). They were kept by individual battalions during the First World War, from the years 1914 to 1922. A junior officer would be responsible for recording the daily movements of the battalion, the operations of conflicts they were involved with and other relevant information (including lists of casualties, although names of officers would only be mentioned and other ranks would mostly be listed by total number killed only). As such they are an invaluable detailed source for understanding the military conflict in a very microscopic fashion. They can be of great use if your ancestor’s service papers do not survive, as the war diaries can act as a substitute service history.

Copies of battalion war diaries were sent to the War Office at the time, and these are kept at The National Archives (series WO 95). However, individual units also retained copies and these can be found in the appropriate regimental museum (where other records for regiments may also be found).

War diaries were also kept during the Second World War and are also retained at The National Archives. They are arranged in a number of series in the WO class arranged by the Order of Battle and then by Command.

Operational Records

It is also possible to trace the history of a campaign or military operation from a wide variety of papers, reports and observations filed at the War Office and other government departments. Most of these official papers are now deposited at The National Archives, and help can be found via research guides online at www.nationalarchives.gov.uk.

Muster Rolls

Another useful source for tracing campaigns is the muster rolls (described above, page 165). As well as tracing an individual soldier’s career they are also useful in finding out the details of the campaigns each battalion was involved in. The lists would state exactly where each battalion was stationed and also give details of any casualties or deaths that occurred during the quarter.

Published Regimental Histories

Most regiments have a proud tradition, and the oldest were created many centuries ago. As such individual regiments often have specific histories written about them which will often detail which campaigns the regiment was involved in and the contribution made by that regiment. They may also contain biographical details of eminent soldiers of that regiment. These histories are often published and can be viewed at The National Archives, The Imperial War Museum, The National Army Museum and other large reference libraries. It is also possible to purchase certain histories, if required, particularly from the regimental museum concerned. A good guide to the range of regimental histories can be found in A Bibliography of Regimental Histories of the British Army compiled by Arthur S. White (London Stamp Exchange, 1988). Additionally, individual regimental museums should also contain this information.

War Histories

There have also been numerous publications on the many campaigns and wars the British Army has been engaged in through its history. Many will have detailed information on specific battles along with helpful footnotes leading you to primary documents if you wish to research these. These books can be found in the major archives and libraries relating to army history, and in larger reference libraries. Many bookshops will also stock the more popular histories. If applicable, it is also worthwhile researching conflicts through contemporary sources such as newspapers to provide information that may not have been included in later histories.

Regimental Museums

Along with specific histories, many regiments also have museums preserving aspects of each regiment’s history. There are 136 military museums scattered throughout the United Kingdom at present. Many of these museums will have regimental records relating to the campaigns they were involved in. They may also have other paraphernalia relating to their campaigns, such as photographs, medals and uniforms worn at the time. Other useful research collections include regimental newspapers and journals. Certain museums may also have donations from ex-soldiers deposited with their holdings. It is possible to find a list of these museums and their contact details at the following website, www.armymuseums.org.uk.

‘Private diaries give a unique and very personal insight into a campaign.’

Private Accounts

Many soldiers would write private journals about their experiences during battle. These provide a very personal and unique insight into the campaign in which they were involved. If your ancestor was in the Army such a diary may be found amongst his personal papers. Otherwise, as mentioned above, the Imperial War Museum holds papers that were donated by individual soldiers.

Life in the Army

National Army Museum

Along with the many regimental museums dedicated to military history, the National Army Museum in Chelsea, London (www. national-army-museum.ac.uk), is the central location for the history of the British Army as a whole. The Museum has significant archives and collections relating to over 500 years of military history. This includes over half a million images from the 1840s onwards. Other items for anyone interested in researching military history include a large collection of army medals and uniforms and over 43,000 printed books including journals, regimental histories and biographies of well-known soldiers. The Museum also has a collection of the different types of weapons used in various conflicts through the ages. There is also a collection of fine and decorative art including paintings, sculptures and ceramics obtained by the British Army through its history. The Museum has been publishing a quarterly journal relating to British Army history since 1921 through the Society of Army Historical Research. These many collections held at the Museum make it indispensable for anyone wishing to gain a fuller picture of the type of life in the Army that your ancestor would have had.

Imperial War Museum

This is another museum dedicated to preserving the history of life in the Army, specifically relating to conflicts from the First World War onwards. It was established in 1917 to record the story of the First World War and the contribution made in that conflict by soldiers from the British Empire. The main museum is based in Lambeth, London. However, there are other branches of the museum at five other sites throughout the country. Along with the personal journals mentioned above, there are collections of medals, firearms, significant film and video archives, and the sound archive has many interviews with ex-soldiers and historic radio broadcasts. The Museum has placed a lot of information online, which at www.iwmcollections.org.uk. As the Museum is related to the history of conflict during the twentieth century it is particularly useful for anyone researching an ancestor who fought during this time.

War Dead

As well as the Commonwealth War Graves Commission, described above, there are other ways to find out more about your ancestors who fell in battle.

Office of National Statistics’ Lists

The Army kept separate lists of births, marriages and deaths relating to serving soldiers. Births were recorded from 1761 to 1994, marriages from 1818 to 1994 and deaths from 1796 to 1994. These registers are now found at the General Record Office and the indexes can be searched online at www.findmypast.com. The registers are not available to view, but if an entry is found in the index it is possible to order the appropriate certificate to obtain the details of death.

Memorials

Many cities, towns and villages have erected war memorials to honour their dead. These became especially prominent after the First World War due to the huge numbers of casualties every village suffered. They usually have details for local residents and can give clues to when a soldier served and where or when he died. It is estimated that there are approximately 70,000 such memorials throughout the United Kingdom. The Imperial War Museum has worked in partnership with English Heritage to create a centralized database of these memorials, and the United Kingdom National Inventory of War Memorials has placed this database of the 55,000 war memorials that have been recorded so far online. The database can be searched free of charge at www.ukniwm.org.uk. The database covers memorials from many wars, starting in the tenth century. It is not possible to search the database by name as the memorials themselves have been listed individually. However, if a memorial was erected to commemorate an individual soldier then that has been listed by his name. Many family history societies have name indexes of war memorials that can be used.

Additionally, there is a database for those who were commemorated for the First World War, and this can be searched by name on the Channel 4 website Lost Generation. The site is dedicated to the history of the First World War, following on from the series of the same name. It is possible to search by the individual soldier’s name on the following page free of charge: www.channel4.com/history/microsites/L/lostgeneration/search/person.html.

Obituaries

It is often worthwhile spending time researching any obituaries that may have been written after a soldier died. This is particularly true of high-ranking officers as local newspapers and, sometimes, national newspapers too would publish obituaries. Obituaries can give useful summaries of the deceased’s career and can give clues for further research into original sources. The newspaper archive is now part of the British Library’s collection, based in Colindale, north-west London. It is possible to search The Times online archive through most local libraries.

Visiting Battlefields

If you are particularly interested in the military history of a conflict then visiting the battlefields can be a very enlightening process. There are specific tour groups for those interested in visiting the more popular battlefield sites from the First and Second World Wars. Details of many of those operating such tours can be found online. It is also possible to visit these sites without using a tour guide, but it would be necessary to have a detailed guidebook to make the visit worthwhile. There are also tours for those interested in visiting famous UK and Irish battlefields along with those in Northern France and Belgium. Touring a battlefield is a very good way to help visualize the actual fighting your ancestor would have been involved in.