Greek Beginnings

It is terrifying to think how much research is needed to determine the truth of even the most unimportant fact.

Stendhal

Sources and Apologia

The birth of irrational numbers took place in the cradle of European mathematics: the Greece of several centuries B.C.E. For this conviction and for much more we must place reliance on a few fragments of contemporary papyrus, some complete but much later manuscripts, and the scholarship of many specialists who, even between themselves, sometimes disagree in fundamental ways. Of great importance is the following passage:

Thales,1 who had travelled to Egypt, was the first to introduce this science [geometry] into Greece. He made many discoveries himself and taught the principles for many others to his successors, attacking some problems in a general way and others more empirically. Next after him Mamercus, brother of the poet Stesichorus, is remembered as having applied himself to the study of geometry; and Hippias of Elis records that he acquired a reputation in it. Following upon these men, Pythagoras transformed mathematical philosophy into a scheme of liberal education, surveying its principles from the highest downwards and investigating its theorems in an immaterial [abstract] and intellectual manner. He it was who discovered the doctrine of proportionals and the structure of the cosmic figures.2

So begins the Eudemian Summary, which forms part of the second of two prologues to A Commentary on the First Book of Euclid’s Elements, written by Proclus (411–485 C.E.), or to give him his full accepted name, Proclus Diadochus (Proclus the Successor), for reasons we shall soon discover. Here Proclus, the last great ancient Greek philosopher, mentions Thales of Miletus (624–546 B.C.E.), who was possibly the first, as he might have been the first pure mathematician. Proclus also mentions Pythagoras of Samos (580–520 B.C.E.), who might have been the second, and with whom the story of irrational numbers, according to what evidence is available, should begin. Our reliance on Proclus3 is not novel and we will call on the distinguished British polymath Ivor Bulmer-Thomas to provide a proper historical perspective:4

It [the Eudemian Summary] is, along with the Collection of Pappus and the commentaries of Eutocius on Archimedes, one of the three most precious sources for the early history of Greek mathematics. In his closing words Proclus expressed the hope that he would be able to go through the remaining books [of Euclid’s Elements] in the same fashion; there is no evidence that he ever did so, but as Book 1 contains definitions, postulates, and axioms underlying all the remainder we have the most important things that he would have wished to say.

We have, then, a few pages of observations written a thousand years after the events they chronicle as a principal source of reliable information about these ancient times, and these take the form of a commentary on part of another paramount source; the most influential, most studied, most copied,5 and most widely read mathematical work ever to be written: Euclid’s Elements. Ironically, the paucity of surviving written material is in no small part due to this iconic work, without which our knowledge of ancient Greek mathematics would be so significantly impoverished. The Greeks’ medium of record was papyrus, made from a grass-like plant originating in the Nile delta and subject to natural and often rapid decomposition, particularly in the comparatively damp Greek climate. In that climate, it was simply not a safe long-term medium of record: it rotted. Those works which were deemed worthy of the considerable expense of being preserved were copied by scribes, perhaps as faithful replicas or perhaps with changes that were thought to be appropriate; the remainder were simply left to decompose. From the same reference, again we hear from Ivor Bulmer-Thomas:

Euclid’s Elements was so immediately successful that it drove all its predecessors out of the field.

It is a simple fact that the prominence of The Elements reduced to irrelevance much that preceded it, condemning the works to obscurity and then oblivion; David Hilbert’s remark, made in the nineteenth century, really sums up the situation quite nicely:

One can measure the importance of a scientific work by the number of earlier publications rendered superfluous by it.

We shall have much need of The Elements later in this chapter but the reader should be clear that we must again rely on secondary sources, since no extant version of it exists. In fact, the earliest surviving copies of the work, held at the Vatican and the Bodleian Library in Oxford, date from the ninth century C.E.; a thousand years after Euclid. That said, some much earlier fragments have been found on potsherds discovered in Egypt dating from around 225 B.C.E. and pieces of papyrus dated from 100 B.C.E.: the former containing notes on two Propositions from Book XIII, and the latter having inscribed parts of Book II.

So, with the Greek’s medium of record fatally inadequate, The Elements relegating untold numbers of earlier works to insignificance, and the effect of providence that accompanies the passing of so many years, we must accept the consequent historical difficulties: and these do not end here. Really, they have their beginning with the Greek custom, until about 450 B.C.E., of transmitting knowledge orally, continue with the fondness on the part of later commentators to exaggerate the contributions of great men and culminate with the staged destruction of the academic riches of Alexandria: the Romans (seemingly in 48 B.C.E.) razed the great Library of Alexandria with its estimated 500,000 manuscripts, the Christians (in 392 C.E.) pillaged Alexandria’s Temple of Serapis with its possible 300,000 manuscripts, and finally the Muslims burnt thousands more of its books (in about 640 C.E.). Add to these the Pythagorean custom of attributing all results to their founder, who appears never to have written anything down, and their (near) strict adherence to their canon of omerta, and we have the ingredients of the mathematical historian’s nightmare; judging veracity and objectivity of the scant available evidence is a responsibility properly undertaken only by a few specialists, upon whom our discussion must rely.

Specifically, as to our knowledge of Pythagoras, the contemporary classicist Professor Carl Huffman provides a dampening perspective6:

. . . any chronology constructed for Pythagoras’ life is a fabric of the loosest possible weave.

He may have been a pupil of Thales and to Proclus can be added significant further material; for example, Plato (428–347 B.C.E.) mentions him as a great teacher in Book X of The Republic, which is dated somewhere around 380 B.C.E. And there are three biographies too: that of Diogenes Laertius (200–250 C.E.), who wrote as part of a ten-volume work on the lives of Greek philosophers, the volume Life of Pythagoras; the other two are those of Iamblichus of Chalcis (ca. 245–325 C.E.), On the Pythagorean Way of Life, and of his teacher, Porphyry (234–305 C.E.) with Life of Pythagoras. All were written about eight hundred years after Pythagoras’ time, but they are at least extant. The definitive modern treatise must surely be that by the German classical scholar Walter Burkert,7, to which we refer the interested and committed reader; we shall be content with the following thumbnail impression of Pythagoreanism, which will suit our own modest needs.

All things are number: such was the Pythagorean dictum central to their philosophy. To them, number meant the discrete positive integers, with 1 the unit by which all other numbers were measured. This meant that all pairs of numbers were each multiples of the unit; that is, all pairs of numbers were commensurable by it. Contrastingly, lengths, areas, volumes, masses, etc., were continuous quantities, the magnitudes which served the ancient Greeks in place of real numbers. Ratios of discrete were conceptually secure and those of magnitudes could be envisaged too, provided that the two values concerned were of the same type. Further, the modern statement

A:B = C:D

was meaningful, where on one side of the equality there are magnitudes of one type and on the other magnitudes of another type. This could mean lengths on one side and areas on the other, and we will see part of the utility of this a little later. Additionally, their study of musical scales revealed that philosophical coincided with musical harmony with cordant sounds found to be measured by integer ratios of lengths of strings with, for example, the octave corresponding to a ratio of length of 2 to 1 and a perfect fourth to 3 to 2, etc. This was evidence to them that the continuous could be measured by the discrete. We will allow Aristotle8 to summarize the situation:

Contemporaneously with these philosophers and before them, the so-called Pythagoreans, who were the first to take up mathematics, not only advanced this study, but also having been brought up in it they thought its principles were the principles of all things. Since of these principles numbers are by nature the first, and in numbers they seemed to see many resemblances to the things that exist and come into being – more than in fire and earth and water (such and such a modification of numbers being justice, another being soul and reason, another being opportunity – and similarly almost all other things being numerically expressible); since, again, they saw that the modifications and the ratios of the musical scales were expressible in numbers; since, then, all other things seemed in their whole nature to be modelled on numbers, and numbers seemed to be the first things in the whole of nature, they supposed the elements of numbers to be the elements of all things, and the whole heaven to be a musical scale and a number. And all the properties of numbers and scales which they could show to agree with the attributes and parts and the whole arrangement of the heavens, they collected and fitted into their scheme; and if there was a gap anywhere, they readily made additions so as to make their whole theory coherent. E.g. as the number 10 is thought to be perfect and to comprise the whole nature of numbers, they say that the bodies which move through the heavens are ten, but as the visible bodies are only nine, to meet this they invent a tenth – the ‘counter-earth’.

With the Pythagoreans’ dogmatism, the stage was set for the crisis in Greek mathematics that was to unfold, as ‘a veritable logical scandal’,9 possibly the very first of the long sequence of them that continues to this day.

So, there are available sources and there are scholars who have mined them of their dependable evidence regarding these remote times. By now, however, we hope that the reader will have a proper appreciation of the intrinsic historical complications and accept that given dates are sometimes approximate and statements made only with the authority borne of a compromise of accepted wisdom.

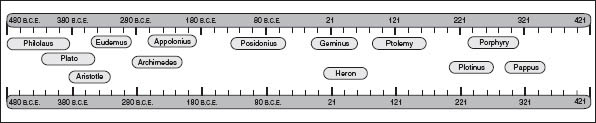

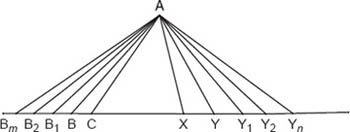

As a final emphasis we can gain some idea of the chain connecting Thales and Pythagoras to Proclus by relying on the scholarly labour of the early twentieth-century Dutch mathematical researcher J. G. van Pesch,10 which includes a detailed study of the works which he deemed were accessible to and directly used by Proclus, whether or not the dependence was explicitly stated. Figure 1.1 shows the resulting timeline of individuals and consists of a mixture of familiar and not-so-familiar names, together with approximate dates. Most particularly, the name of Eudemus of Rhodes (350–290 B.C.E.) appears, an historian who is attributed with writing a long-lost history of Greek geometry covering the period prior to 335 B.C.E.; it is, in particular, this formative work that van Pesch (and others) are confident that Proclus had at his disposal and summarized: hence Eudemian Summary.

Figure 1.1.

Yet, two names on van Pesch’s list are missing from the timeline, since the dates of these individuals are simply not known. The first is Carpus of Antioch, or ‘Carpus the Engineer’, to whom Proclus attributed the definition that an angle is a quantity, specifically, the distance between the containing lines or planes; he is also the person accredited by Iamblichus of Chalcis as being among the Pythagoreans who solved one of the three great problems of antiquity: that of the impossibility of squaring the circle. He appears to have lived at some time between 200 B.C.E. and 200 C.E.

The second name is that of Syrianus of Alexandria, himself a commentator on Plato and Aristotle, and through him we can learn a little about Proclus himself. The revival of Plato’s academy under the leadership of Plutarch (46–120 C.E.) brought important scholars to Athens, among whom was the philosopher Syrianus and a young man, about 20 years old and of immense promise, by the name of Proclus. Such was his promise that for a short time before his death the aged Plutarch agreed, exceptionally, to tutor Proclus. When Syrianus replaced Plutarch as leader he also replaced him as tutor to Proclus. In his turn, Proclus succeeded Syrianus as head of the academy; it was this event that brought about the addition of Diadochus (Successor) to his name. The relationship between Proclus and Syrianus was to become intellectually and emotionally immensely close, so much so that Proclus left instructions that, on his death, he be placed in the tomb already occupied by Syrianus. The tomb was located on the slopes of the Lycabettus Hill, overlooking Athens, a limestone peak of some 1000 feet and, for very good reasons, a modern tourist attraction. The level of affection is easily judged by Proclus’ decree that the following epitaph be inscribed on their joint resting place:

Proclus was I, of Lycian race, whom Syrianus

Beside me here nurtured as a successor in his doctrine.

This single tomb has accepted the bodies of us both;

May a single place receive our two souls.

As with so much else, the tomb has long ago disappeared.

With the authority of Proclus, Thales, the first of the Seven Sages of Greek tradition, brought geometry from Egypt to Greece. In particular, as the Commentary develops, Proclus attributes to him the following four geometric results:

1. A circle is bisected by any diameter.

2. The base angles of an isosceles triangle are equal.

3. The angles between two intersecting straight lines are equal.

4. Two triangles are congruent if they have two angles and one side equal.

These seem modest achievements. Yet their simplicity belies their significance, as they exhibit the germ of the deductive procedures of Greek philosophy being brought to bear on mathematical processes: the yet more ancient Egyptian and Babylonian civilizations had no thought of axiomatics, abstraction or generalization, with mathematical results having the form of mysterious individual recipes. This is not to say that some of the knowledge could not be called ‘advanced’, it is simply that the deductive method that we consider as an essential aspect of pure mathematics was entirely absent. Paradoxically, evidence abounds regarding these older civilizations; the ancient Egyptians used papyrus too, but their climate was more papyrus-friendly than Greece, and the Babylonians wrote in cuneiform on wet clay tablets, thousands of which have survived.

To gain a perspective of the magnitude of the step that had been taken by Thales we will trouble to annotate two contemporary examples, one from each of these civilizations.11 From the Moscow papyrus, which dates from around 1850 B.C.E., we have an Egyptian problem:

Method of calculating a

If you are told  of 6 as height, of 4 as lower side, and of 2 as upper side.

of 6 as height, of 4 as lower side, and of 2 as upper side.

You shall square these 4. 16 shall result.

You shall double 4. 8 shall result.

You shall square these 2. 4 shall result.

You shall add the 16 and the 8 and the 4. 28 shall result.

You shall calculate  of 6. 2 shall result.

of 6. 2 shall result.

Figure 1.2.

You shall calculate 28 times 2. 56 shall result.

Look, belonging to it is 56.

What has been found by you is correct.

Here the  is our

is our  , which means that the calculation is

, which means that the calculation is  × 6 × (42 + 4 × 2 + 22) = 56, a special case of the general formula for the volume of the frustram of a square pyramid, V =

× 6 × (42 + 4 × 2 + 22) = 56, a special case of the general formula for the volume of the frustram of a square pyramid, V =  h(a2+ab+b2), with this special case shown in figure 1.2.

h(a2+ab+b2), with this special case shown in figure 1.2.

And from a Babylonian tablet from about 2000–1600 B.C.12:

A circle was 1 00.

I descended 2 rods.

What was the dividing line (that I reached)?

You:  you

you

Square

Square <double> 2.

<double> 2.

You will see 4.

Take away  you will see

you will see 4 from 20, the dividing line.

4 from 20, the dividing line.

You will see 16.

Square 20, the dividing line.

You [will see] 6 40.

Square 16.

You will see 4 16.

Take away 4 16 from 6 40.

You will see 2 24.

What squares 2 24?

12 squares it, the dividing line.

That is the procedure.

The Babylonians used base 60. With that in mind, the instructions refer to figure 1.3, a circle of circumference 1 00 in base 60 and so 60 units in base 10 and describe a procedure for calculating the length of the chord (‘the dividing line that I reached’) 2 units in from the circle itself. The mysterious 20 emerges from the fact that, if the circle has radius r, 2πr = 60 and, with π taken as 3, 2r = 20 ( was another approximation for π).

was another approximation for π).

Figure 1.3.

In modern notation, with a chord of length 2l we have

(2l)2 = (2r)2 − (2r − 22)2,

which simplifies to

l2 = r2 − (r − 2)2,

and this is no more than an application of Pythagoras’s Theorem, at least a thousand years before Pythagoras.

These are typical of their kind, with the underlying principles entirely hidden and no hint of general results being appreciated. The great seventeenth-century German philosopher Immanuel Kant encapsulated the transition from Egyptian–Babylonian instruction sets to Greek mathematics in the following manner13:

In the earliest times to which the history of human reason extends, mathematics, among that wonderful people, the Greeks, had already entered upon the sure path of science . . . A new light flashed upon the mind of the first man (be he Thales or some other) who demonstrated the properties of the isosceles triangle. The true method, so he found, was not to inspect what he discerned either in the figure, or in the bare concept of it, and from this, as it were, to read off its properties; but to bring out what was necessarily implied in the concepts that he had himself formed a priori, and had put into the figure in the construction by which he presented it to himself.

With this, the direction of mathematical progress was determined as that of a science: from ‘reasonable’ assumptions deduce logical conclusions. The infamous parallel postulate of Euclid serves as the second example of such an assumption concealing within it formative complications: the assumption of universal commensurability is the first.

The Unmentionable Incommensurable

Thales may have started mathematics on what Kant described as the “royal road of science” but tradition has it that it was Pythagoras who guided it along that path, not very far along which lay the concept of incommensurability, the Greeks’ perception of what we now call irrationality.

Recall that, to the Pythagoreans, all things were measured by number; that is, by positive integers, or the ratio of two of them. Recall further that it was their conviction that the word all embraced continuous magnitudes such as length, area and volume, which meant that not only were the cordant notes produced by plucking strings so constrained but also the strings which produced those notes: that is, any two lengths were commensurable with each other, not this time with a single unit measuring them but the much more mysterious unspecified and variable unit. That is, given two lines of different lengths (two different magnitudes), for the Pythagoreans there must exist a third line which subdivides both of them perfectly, the length of which is their common unit. (Of course, any subdivision of that line would also be a unit.) In modern notation, if one line is of length l1 and another of length l2 and the common unit is u there must exist integers n1 and n2 such that l1 = n1u and l2 = n2u. The consequence of this is that the ratio of any two magnitudes is the ratio of two integers, l1:l2 = n1u:n2u = n1:n2. And a great deal more than philosophical expediency depends on this outcome, as we shall see.

Unfortunately, it does not appear to have taken long for the logical fault-line associated with this approach to magnitudes to be exposed, but how it was uncovered and by whom are matters of academic debate.

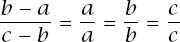

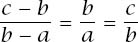

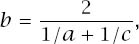

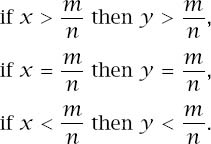

One possibility is that the Pythagorean interest in the concept of the mean of two numbers may have directed their attention to the nature of the geometric mean of 1 and 2; 1 the monad which generates all numbers and 2 the dyad and first feminine symbol. The general approach seems to have been to consider two numbers a and c and to define a third number b, which is a mean of them, with a  b

b  c. The method was to note that each of b−a, c−b and c−a is

c. The method was to note that each of b−a, c−b and c−a is  0 and that the ratio of any pair of these can be compared with that of any pair of the original numbers, with the three fundamental examples in modern notation:

0 and that the ratio of any pair of these can be compared with that of any pair of the original numbers, with the three fundamental examples in modern notation:

to yield

to yield  the arithmetic mean;

the arithmetic mean;

to yield

to yield  the geometric mean;

the geometric mean;

to yield

to yield  the harmonic mean.

the harmonic mean.

With the geometric formula giving

we have the appearance of  .

.

This said, tradition has it that the author of the destruction of the Pythagorean ideal was none other than an acolyte: Hippasus of Metapontum, a man who has a decidedly negative Pythagorean press. Not only is he accused of destroying the concept of commensurability, he is meant to have spoken of the horror outside the secretive Pythagorean community – and he is meant to have done the same with his discovery that a dodecahedron can be inscribed within a sphere. With the authority of Iamblichus of Chalcis, whom we mentioned earlier and who was to have a considerable influence on Proclus14:

They say that the man who first divulged the nature of commensurability and incommensurability to men who were not worthy of being made part of this knowledge, became so much hated by the other Pythagoreans, that not only they cast him out of the community; they built a shrine for him as if he were dead, he who had once been their friend. Others add that even the gods became angry with him who had divulged Pythagoras’ doctrine; that he who showed how the dodecahedron can be inscribed within a sphere died at sea like an evil man. Others still say that the same misfortune happened on him who spoke to others of irrational numbers and incommensurability.

The Pythagoreans may, according to Aristotle, have been able to invent a ‘counter-earth’ to fit in with their cosmological views but incommensurability was not so easily disposed of. The ratio of two magnitudes was now not necessarily defined, and this meant that the fundamental geometric tool of similarity was denied them – and all results depending on its use, as we shall see.

Mention of the phenomenon is made by Plato in several of his Dialogues, and these reveal an interesting linguistic development: in the Hippias Major (if indeed he was its author) and The Republic incommensurables are referred to as αρρετoς, or unmentionable, whereas in the later Dialogues, Theaetetus and Laws the change is to µχειoσµµετρoι, or incommensurable. We shall soon see how this mutated to surd.

Whether it was Hippasus or another who discovered incommensurability and whether or not this was achieved through the study of means is not known; the method of proof remains yet another mystery but it is popular tradition that he applied his master’s theorem to a square of side 1 unit, somehow showing that its diagonal of length  was incommensurable with the unit side. Such an argument appears in Book X, Appendix 27, of The Elements, as shown below15:

was incommensurable with the unit side. Such an argument appears in Book X, Appendix 27, of The Elements, as shown below15:

Let ABCD be a square and AC its diameter. I say that AC is incommensurable with AB in length. For let us assume that it is commensurable. I say that it will follow that the same number is at the same time even and odd. It is clear that the square on AC is double the square on AB. Since then (according to our assumption) AC is commensurable with AB, AC will be to AB in the ratio of an integer to an integer. Let them have the ratio DE:DF and let DE and DF be the smallest numbers which are in this proportion to one another. DE cannot then be the unit. For if DE was the unit and is to DF in the same proportion as AC to AB, AC being greater than AB, DE, the unit, will be greater than the integer DF, which is impossible. Hence DE is not the unit, but an integer (greater than the unit). Now since AC:AB = DE:DF, it follows that also AC2:AB2 = DE2:DF2. But AC2 = 2AB2 and hence DE2 = 2DF2. Hence DE2 is an even number and therefore DE must also be an even number. For, if it was an odd number, its square would also be an odd number. For, if any number of odd numbers are added to one another so that the number of numbers added is an odd number the result is also an odd number. Hence DE will be an even number. Let then DE be divided into two equal numbers at the point G. Since DE and DF are the smallest numbers which are in the same proportion they will be prime to one another. Therefore, since DE is an even number, DF will be an odd number. For, if it was an even number, the number 2 would measure both DE and DF, although they are prime to one another, which is impossible. Hence DF is not even but odd. Now since DE = 2EG it follows that DE2 = 4EG2. But DE2 = 2DF2 and hence DF2 = 2EG2. Therefore DF2 must be an even number, and in consequence DF is also an even number. But it has also been demonstrated that DF must be an odd number, which is impossible. It follows, therefore, that AC cannot be commensurable with AB, which was to be demonstrated.

A simple sketch and a little patience reveal the argument which, in modern algebraic form, is greatly familiar.

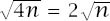

Suppose that  = a/b, where a and b are integers in their lowest terms. Then a2 = 2b2 and so a2 is even and therefore a is even. Write a = 2k, then a2 = 4k2 and so 2b2 = 4k2 and therefore b2 = 2k2, which makes b even and we have a contradiction to the assumption that the two numbers are in lowest terms.16

= a/b, where a and b are integers in their lowest terms. Then a2 = 2b2 and so a2 is even and therefore a is even. Write a = 2k, then a2 = 4k2 and so 2b2 = 4k2 and therefore b2 = 2k2, which makes b even and we have a contradiction to the assumption that the two numbers are in lowest terms.16

In its geometric form the inherent beauty of the argument is concealed but it stands, with the infinitude of the primes, as one of the two most elegant and elementary proofs of mathematics, each chosen for those reasons by G. H. Hardy for inclusion in his Mathematician’s Apology.

Figure 1.4.

Yet, there is a sustainable view that this Euclidean neatness is an example of The Elements presenting a later rather than an original approach and we will now follow an alternative path which leads to the annihilation of Pythagorean commensurability.17

Signs of Danger

It can be of little surprise that, over the ages, commentators have remarked on the mystical significance the Pythagoreans attached to some shapes. For example, if we look to the original Oxford English Dictionary’s 1908 entry for Pythagorean we see its famous editor, James Murray, allowing the capital Greek letter upsilon (ϒ) to be their representation of the two divergent paths of virtue and vice. The equally prestigious American initiative, the Century Dictionary, has the 1906 entry Hexagram attaching the regular hexagon and its associated hexagram to Pythagorean mysticism. Modern versions of these publications and others like them are consistent with their illustrious predecessors. The great classical scholar Sir Thomas Heath, to whom we have already referred, cites Lucian of Samosata (125–180 C.E.) and the scholist to the far earlier play of Aristophanes, The Clouds, as authority that the pentagon and associated pentagram were symbols of Pythagorean recognition.

Square, Pentagram, Hexagram – no matter: they each conceal commensurability’s doom without the need of Pythagoras’s theorem; their own sacred symbols were harbingers of their philosophical destruction.

To consider the matter, first we need to look at an immediate consequence of the definition of commensurability, one which is widely applied in The Elements:

Referring to figure 1.4, if AD and AE are commensurable, then it must be that AD and AD − AE are commensurable.

Figure 1.5.

The result is obvious and its proof trivial but, undeterred by either fact, let us suppose that AD and AE are commensurable with a unit u and that AD = Nu and AE = nu, then AD − AE = Nu − nu = (N − n)u, which indeed means that AD and AD − AE are commensurable by the unit u.

Now consider the square as shown in figure 1.5, with the line AED located as a diagonal, where the point E is defined in the first part of the following construction.

Select the point E on the diagonal AD so that AE = AB and drop the perpendicular EF. Now consider the segment ED and move a copy of it vertically downwards as the segment GH, thereby creating a parallelogram DEGH, and consider what happens to the size of  BGH. Initially, when GH was the same as ED with

BGH. Initially, when GH was the same as ED with  BGH =

BGH =  BED > 90° and finally, when G becomes F,

BED > 90° and finally, when G becomes F,  BGH =

BGH =  BFH < 90°. Since the process is continuous, there must be a position of GH so that

BFH < 90°. Since the process is continuous, there must be a position of GH so that  BGH = 90°; let that be the position shown in the figure and consider the right-angled isosceles triangle BGH. If AD is commensurable with AB, then it is commensurable with AE and so, using the above observation, AD is commensurable with AD − AE = ED = GH. Now let GH be the diagonal of the next square and the process can be repeated indefinitely with ever smaller nested triangles to ensure that no unit of commensurability can exist. It must be that AD is incommensurable with AB, never mind using Pythagoras’s theorem to find the length.

BGH = 90°; let that be the position shown in the figure and consider the right-angled isosceles triangle BGH. If AD is commensurable with AB, then it is commensurable with AE and so, using the above observation, AD is commensurable with AD − AE = ED = GH. Now let GH be the diagonal of the next square and the process can be repeated indefinitely with ever smaller nested triangles to ensure that no unit of commensurability can exist. It must be that AD is incommensurable with AB, never mind using Pythagoras’s theorem to find the length.

Figure 1.6.

So the simple square, the first of the regular shapes gifted with Pythagorean mystical significance, conceals the means of commensurability’s destruction. Now let us look at a second, the regular pentagon; a figure redolent with hidden meaning which gives rise to that Pythagorean symbol of recognition, most commonly known as the pentagram.

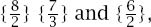

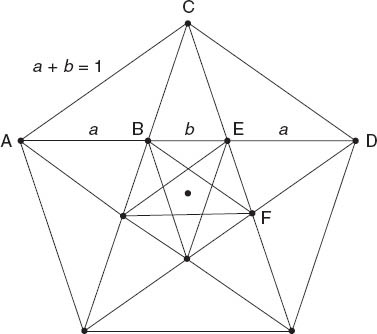

The pentagram, pentalpha, pentangle or star pentagon is one of the most potent, powerful and persistent symbols in the history of humankind. It has been throughout the ages a symbol used by pagans, ancient Israelites, Christians, magicians, Wiccans and many more cults. Sir Thomas Mallory in Le Morte d’Arthur had Sir Gawain adopt it as his personal symbol to be placed it on his shield and Dan Brown in The Da Vinci Code had the dying Louvre museum curator Jacque Saunière draw one on his abdomen in his own blood as a clue to identify his murderer. It can be realized with or without its defining regular pentagon or circumscribing circle, as we see in figure 1.6. For the mathematician it is the simplest example of a star polygon: each of five regularly spaced points having been connected by a straight line to another, with the general case having the connection made between every mth point of the n points, with the resulting figure commonly given the symbol {n/m}. For reasons of common sense and aesthetics it is usually assumed that m and n are relatively prime, n > 2m and that the points are equidistant from the figure’s obvious centre; with this notation, the pentagram is given the symbol  Other examples,

Other examples,  are shown in figure 1.7, the last of which will attract our attention in a few lines.

are shown in figure 1.7, the last of which will attract our attention in a few lines.

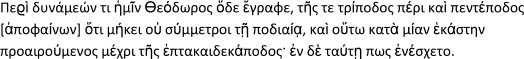

If we consider the pentagram with its defining regular pentagon, the eye is led to its many congruent or similar isosceles triangles and to the nested regular pentagon, inverted and suggestive of an infinitely recursive extension of the figure, the next stage of which is shown in figure 1.8. Once again we can force a contradiction in much the same manner as with the square. This time locate the line AED as a diagonal of the pentagon and suppose that the diagonal AD and the side AC of the large pentagon are commensurable. We have AD − AC = AD − AE = ED = AB and AB = BC = BF, with BF a diagonal of the inner pentagon. Since AD and AD − AE = AB = BF are commensurable, AD, the diagonal of the original pentagon must be commensurable with BF, the diagonal of the smaller, nested pentagon. Once again, since the process can be continued indefinitely, whatever the supposed unit that measures both AD and AE it will eventually be bigger than the length of the diagonal of a nested pentagon; inescapably, there can be no such common measure.

Figure 1.7.

Figure 1.8.

Finally (and it must be finally, as we will soon mention), that  star polygon, the regular hexagon, can be used to generate the same infinite process. Its associated double overlapping equilateral triangles, the hexagram, is again one of the oldest and most widespread spiritual symbols, whether it be called the Seal of Solomon, the Star of David, the Shatkona or, from the Hebrew, the workings of the Seven Planets under the presidency of the Sephiroth and of Ararita, the divine name of Seven letters; and once again Dan Brown made use of it in that same novel. For the first time the diagonals are not all of the same length, with the longest one evidently commensurable with the side, being twice its length. But what about the shorter diagonals? We now locate the line AED as such a diagonal, as shown in figure 1.9, where E is defined so that AE = AY. Now define point X on DY produced by the condition that

star polygon, the regular hexagon, can be used to generate the same infinite process. Its associated double overlapping equilateral triangles, the hexagram, is again one of the oldest and most widespread spiritual symbols, whether it be called the Seal of Solomon, the Star of David, the Shatkona or, from the Hebrew, the workings of the Seven Planets under the presidency of the Sephiroth and of Ararita, the divine name of Seven letters; and once again Dan Brown made use of it in that same novel. For the first time the diagonals are not all of the same length, with the longest one evidently commensurable with the side, being twice its length. But what about the shorter diagonals? We now locate the line AED as such a diagonal, as shown in figure 1.9, where E is defined so that AE = AY. Now define point X on DY produced by the condition that  AEX = 60°, then XED forms two adjacent sides of a smaller regular hexagon, with shorter diagonal DX. If AD is commensurable with AY then AD is commensurable with AE and so, using the initial result once more, with ED, the side of the new regular hexagon; the infinite process is again started, leading to the demolition of the assumption of commensurability.

AEX = 60°, then XED forms two adjacent sides of a smaller regular hexagon, with shorter diagonal DX. If AD is commensurable with AY then AD is commensurable with AE and so, using the initial result once more, with ED, the side of the new regular hexagon; the infinite process is again started, leading to the demolition of the assumption of commensurability.

Figure 1.9.

In modern terms, the diagonal of the unit square,  , is irrational, as are the diagonals of the regular pentagon and shorter diagonal of the regular hexagon. We can satisfy ourselves which irrationals these last two are in the following manner.

, is irrational, as are the diagonals of the regular pentagon and shorter diagonal of the regular hexagon. We can satisfy ourselves which irrationals these last two are in the following manner.

Again, using the notation of figure 1.8 and the symmetry of the pentagram we know that, with a side of 1 unit, AE = AC = a + b = 1, and also that the two triangles ABC and ACD similar. This last fact means that

Figure 1.10.

which becomes a2 + a − 1 = 0, and this makes  and the length of the diagonal

and the length of the diagonal

2a + b = 2a + (1 − a) = 1 + a = 1 +  (−1 +

(−1 +  ) =

) =  (1 +

(1 +  ) =

) =  ,

,

which is the Golden Ratio, also exposed as the Greek mean of 1 and 2 (as mentioned on page 20), defined by

It is a further irony that this ‘division into mean and extreme ratio’, so revered in Greek mathematics and seemingly so much part of their architecture, should be central to the ruin of its earliest mathematical precept.

Finally, it is a trivial matter to see that the shorter diagonals of the regular hexagon of side 1 unit are of length  .

.

Quite remarkably, the argument fails thereafter; that is, trying to force the infinite regress for regular polygons of sides greater than 6 is doomed to failure, as shown in a beautiful but lengthy argument by E. J. Barbeau.18

So, these important Pythagorean symbols have embodied within them all that is needed to destroy their cherished ideal of commensurability and as if that were not enough so does another of a different type: the Vesica Pisces or Vessel of the Fish, which, to the Pythagoreans, was a symbolic womb giving life to the entire universe. The figure is formed by allowing two circles of equal radii to overlap and pass through the centre of the other, as in figure 1.10, and if the circles have radius 1 then lines of length  ,

,  (and

(and  ) are easily found within the figure, as is

) are easily found within the figure, as is  if we allow the lengths of two of them to be added.

if we allow the lengths of two of them to be added.

Of course, we cannot be certain whether it was Hippasus or not and whether it was the diagonal of a square or of a pentagram or of a hexagram or whatever that destroyed Pythagorean commensurability, but whoever the architect and whatever his methods, this was to be a revelation that placed a boulder in the royal mathematical path which was not to be circumvented for a century.

Signs of Progress

Plato (429–347 B.C.E.): student and acolyte of Socrates, teacher of Aristotle, author of the Dialogues and founder of the Academy and who, according to the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy,

is, by any reckoning, one of the most dazzling writers in the Western literary tradition and one of the most penetrating, wide-ranging, and influential authors in the history of philosophy.

We have already mentioned that he alluded to incommensurability in several of his Dialogues, the dates of which are matters of dispute, although it seems plain that they began after the suicide of Socrates in 399 B.C.E. and, since Plato died in 347 B.C.E., we have a clear window of time through which to peer. What is not in dispute is the importance of Socrates to them and indeed they form the principal source (along with Xenophon’s Memorabilia of Socrates) of the great philosopher’s achievements; as with Pythagoras, there is a complete absence of anything written by him. Although the exact dates of the Dialogues are questioned, there is reasonable concord concerning the order of them and we will mine three of them from, what might be termed, the Early, Middle and Late periods, for news of progress with irrational numbers.

From the Early Hippias Major we learn something of the progress made in the arithmetical properties of rationals and irrationals, with Socrates asking of Hippias19:

To which group, then, Hippias, does the beautiful seem to you to belong? To the group of those that you mentioned? If I am strong and you also, are we both collectively strong, and if I am just and you also, are we both collectively just, and if both collectively, then each individually so, too, if I am beautiful and you also, are we both collectively beautiful, and if both collectively, then each individually? Or is there nothing to prevent this, as in the case that when given things are both collectively even, they may perhaps individually be odd, or perhaps even, and again, when things are individually irrational quantities they may perhaps both collectively be rational, or perhaps irrational, and countless other cases which, you know, I said appeared before my mind?

And then the later Early Transitional Dialogue, Meno, has Socrates asking Meno’s boy slave how to find the side of a square the area of which is double that of a given square. The resulting exchanges between Socrates and the boy are a model of the Socratic approach to teaching, with the boy being led from his first incorrect suggestion that the new square should have side double that of the original to the eventual correct answer of the side being the diagonal of the first square. With this dialogue, what we would call  is acknowledged.

is acknowledged.

But it is with the Late Transitional Dialogue, Theaetetus, that we are most interested, since this at once provides clear evidence of specific progress but also a hint at its limited nature. One of two contemporary dialogues featuring the then dead Theaetetus (the other being Sophist), they combine to form an eloquent testament of the high regard in which Theaetetus of Athens (417–369 B.C.E.), his former student, was held by Plato. With Socrates inevitably as another main character, the third was Theodorus of Cyrene (465–398 B.C.E.), himself one-time teacher of both Plato and Theaetetus.

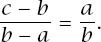

It is in an early passage in Theaetetus that incommensurability reappears and which, somewhat exotically but for good reason, we give initially in the original Greek:

Theodorus was writing out for us something about roots, such as the roots of three or five, showing that they are incommensurable by the unit: he selected other examples up to seventeen − there he stopped.

The words are those which Plato put into the mouth of Theaetetus as he discusses with Socrates the nature of knowledge. Theaetetus recalls to Socrates the memory of Theodorus demonstrating to him the incommensurability of the (implied) non-square integers from  to

to  .

.

Evidently, then, progress had been made in those intervening years, even though its extent is far from clear; most particularly, there is the implication that Theodorus was in possession of no general method of establishing incommensurability, otherwise, why would he repeat his demonstration for each integer?

The final part of the passage is sufficiently intriguing for us to provide another translation of it20:

. . . up to the one of 17 feet; here something stopped him (or: here he stopped) . . .

and one such more21

. . . up to seventeen square feet, ‘at which point for some reason he stopped’.

The Greek, it appears, is ambiguous: did Theodorus stop at, or before, 17? Whatever the answer to this question, why did he stop there? And does this curtailment suggest something about the method he used to establish the incommensurability?

It is natural that these issues have attracted the attention of scholars, as it is natural that groups of them disagree. Certainly, by this time the incommensurability of  was well known and accepted. The earlier implicit mention in Meno is strongly supported by Plato’s comment in a letter of rejection to the sponsor of a student to the academy:

was well known and accepted. The earlier implicit mention in Meno is strongly supported by Plato’s comment in a letter of rejection to the sponsor of a student to the academy:

He is unworthy of the name of man who is ignorant of the fact that the diagonal of a square is incommensurable with its side.

But in the dialogue itself he had Theaetetus continue with22:

Now as there are innumerable roots, the notion occurred to us of attempting to include them all under one name or class.

Which makes it clear that 17 is not an obvious place to stop. The reason for him stopping at or before 17 has been argued by scholars in sometimes ingenious and inevitably varied ways, including one of striking pragmatism from G. H. Hardy and E. M. Wright23 that

he may well have been quite tired.

There is a particular explanation that has a peculiar intrigue though, as it appeals to the confidently established fact that, for Pythagoreans (and Theodorus was a Pythagorean), the parity of number was of the greatest moment, a point emphasized by the late mathematician and mathematical historian Bartel van der Waerden (ibid.):

For the Pythagoreans, even and odd are not only the fundamental concepts of arithmetic, but indeed the basic principles of all nature.

With their definition of even and odd:

An even number is that which admits of being divided, by one and the same operation, into the greatest and the least (parts), greatest in size but least in quantity while an odd number is that which cannot be so treated, but is divided into two unequal parts.

The point is that the parity approach that established the irrationality of  , as shown on page 22, has a generalization. It is described in and may have originated with an elusive article24 by the amateur German mathematician J. H. Anderhub and resurfaced in Wilbur Knorr’s unpublished Ph.D. dissertation, later expanded by him to an expensive book,25 with the historical implications later taken up by Robert L. McCabe.26

, as shown on page 22, has a generalization. It is described in and may have originated with an elusive article24 by the amateur German mathematician J. H. Anderhub and resurfaced in Wilbur Knorr’s unpublished Ph.D. dissertation, later expanded by him to an expensive book,25 with the historical implications later taken up by Robert L. McCabe.26

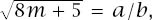

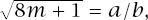

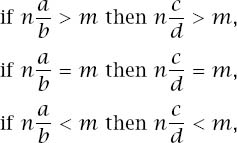

The observation is that 17 is the first non-square integer of the form 8m + 1 and for integers of this form the even−odd parity argument fails: that is, Theodorus stopped before 17 and could, using his approach, proceed no further. A form of the reasoning behind the assertion is as follows:

Since any positive integer can be written as one of 4n, 4n + 1, 4n + 2, 4n + 3 for n = 0, 1, 2, . . . , we can deal with all of them by considering each category separately.

(1) If the integer is of the form 4n its square root is  and we can deal with the case as if it was the number n.

and we can deal with the case as if it was the number n.

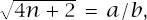

(2) Temporarily omitting the case of 4n + 1, suppose the integer is of the form 4n + 2 and write  where a and b are relatively prime. Then a2 = (4n + 2)b2, which means that a2 is even and therefore a is even. Write a = 2k to get a2 = 4k2 = (4n + 2)b2 and so (2n + 1)b2 = 2k2 and therefore b2 is even and so b is even. A contradiction.

where a and b are relatively prime. Then a2 = (4n + 2)b2, which means that a2 is even and therefore a is even. Write a = 2k to get a2 = 4k2 = (4n + 2)b2 and so (2n + 1)b2 = 2k2 and therefore b2 is even and so b is even. A contradiction.

(3) Now suppose that the integer is of the form 4n + 3 and write  where a and b are relatively prime. Then a2 = (4n + 3)b2. Now, a and b cannot both be even and so at least one of them must be odd and this means that its square is odd; whichever it is, using the previous equation we can conclude that the square of the other must be odd and so itself is odd, therefore, both a and b must be odd. Write a = 2k + 1 and b = 2l + 1 to get (2k + 1)2 = (4n + 3)(2l + 1)2, which becomes

where a and b are relatively prime. Then a2 = (4n + 3)b2. Now, a and b cannot both be even and so at least one of them must be odd and this means that its square is odd; whichever it is, using the previous equation we can conclude that the square of the other must be odd and so itself is odd, therefore, both a and b must be odd. Write a = 2k + 1 and b = 2l + 1 to get (2k + 1)2 = (4n + 3)(2l + 1)2, which becomes

With the left-hand side evidently even and the right odd. Again, a contradiction.

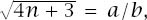

(4) Finally, suppose that the integer is of the form 4n + 1, then either n is even or odd. If n is odd it is of the form 2m + 1 and so our number will be of the form 4(2m + 1) + 1 = 8m + 5. We repeat the above arguments to get  where a and b are relatively prime, and so a2 = (8m + 5)b2 and again this means that both a and b must be odd. Write a = 2k + 1 and b = 2l + 1 to get (2k + 1)2 = (8m + 5)(2l + 1)2, which becomes

where a and b are relatively prime, and so a2 = (8m + 5)b2 and again this means that both a and b must be odd. Write a = 2k + 1 and b = 2l + 1 to get (2k + 1)2 = (8m + 5)(2l + 1)2, which becomes

Since the product of two consecutive integers must be even this means that the left-hand side is even and the right odd. A contradiction once more.

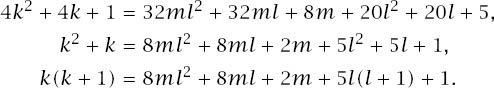

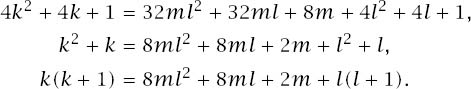

We are left with the final case that the integer is of the form 4n + 1 with n = 2m even and so it is of the form 4(2m) + 1 = 8m + 1 and now the process fails since, if  where a and b are relatively prime, then a2 = (8m + 1)b2 and again this means that both a and b must be odd. Write a = 2k + 1 and b = 2l + 1 to get (2k + 1)2 = (8m + 1)(2l + 1)2, which becomes

where a and b are relatively prime, then a2 = (8m + 1)b2 and again this means that both a and b must be odd. Write a = 2k + 1 and b = 2l + 1 to get (2k + 1)2 = (8m + 1)(2l + 1)2, which becomes

And both sides are even: no contradiction this time.

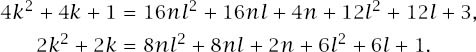

To check, if we attempt an even−odd parity argument with  we are led nowhere.

we are led nowhere.

Write  = a/b, where a and b are relatively prime, then a2 = 17b2, which again means that both a and b are odd. Writing a = 2k + 1 and b = 2l + 1 now yields

= a/b, where a and b are relatively prime, then a2 = 17b2, which again means that both a and b are odd. Writing a = 2k + 1 and b = 2l + 1 now yields

There is no contradiction and taking even−odd cases for k and l simply leads to ever more cases.

Whether or not this is the explanation for Theodorus’s curtailment of his demonstration we will probably never know, but it is assuredly worth considering as a possibility. In 1942 Anderhub posited a more practical justification, simple, appealing and quite devoid of historical probity: had Theodorus been using a sandbox for his demonstrations, as shown on page 7 of the front matter, he would have overlapped after the hypotenuse of the last triangle is  , making the further demonstration impractical. The figure is constructed as follows. On the hypotenuse of a right-angled isosceles triangle of side 1 is drawn a second right-angled triangle,27 whose second side is also 1 and the process continued until the hypotenuse of the last triangle is

, making the further demonstration impractical. The figure is constructed as follows. On the hypotenuse of a right-angled isosceles triangle of side 1 is drawn a second right-angled triangle,27 whose second side is also 1 and the process continued until the hypotenuse of the last triangle is  , where the central angle generated is

, where the central angle generated is

The mathematics of the spiral, the Spiral of Theodorus, associated with the argument (and very much more) was later investigated by Philip J. Davis et al.28

The Loss of Similarity

So, the philosophically unacceptable concept of incommensurability had entered the Pythagorean world and through it that of the ancient Greeks in general, with its appearance bringing about the instant demise of the cherished idea that number (positive integers) was the hand-maiden of geometry. The incommensurability of these constructed lengths separated the concepts of arithmetic ratios (which must for them be ratios of positive integers) and the constructible magnitudes of geometry; geometry could cope with the likes of  in a way that their arithmetic could not. So, the first significant implication of what we now call irrationality was that mathematical enquiry became geometric enquiry, an approach which was to pervade all European mathematics and last well into the eighteenth century. A second was that the familiar implications of the comparison of similar figures absconded – and all proofs which rely on them.

in a way that their arithmetic could not. So, the first significant implication of what we now call irrationality was that mathematical enquiry became geometric enquiry, an approach which was to pervade all European mathematics and last well into the eighteenth century. A second was that the familiar implications of the comparison of similar figures absconded – and all proofs which rely on them.

Figure 1.11.

To see this, consider what we would call two similar triangles; that is, triangles with corresponding angles equal, and suppose that they are labelled ABC and PQR as shown in figure 1.11. We wish to extract the three corresponding ratios of sides and to do so we have no Pythagorean alternative but to recourse to commensurability. So, suppose that sides BC and QR are commensurable with a common unit a. Suppose further that BC is composed of n of these units and QR is composed of m of them and so divide each line into n and m equal segments, each of length a. In triangle ABC, from the right endpoint of each segment, we draw a line parallel to AB to meet side AC and then repeat this for the corresponding points on AC, drawing lines parallel to the side BC; finally, draw the lines parallel to AC to meet BC. By this means AC will have been divided into n equal segments, say of length b, and similarly AB will have been divided into n equal segments, say of length c, and triangle ABC will have been tessellated by congruent triangles of sides a, b and c. Now move to the similar triangle PQR. By this process it too has been tessellated by these same congruent triangles and this means that we have the proportions of sides as

The ratio of the lengths of the sides of similar triangles is the ratio of two integers: very Pythagorean.

Now let us demonstrate why this makes the escape into geometry simply an escape into another mathematical prison cell.

Figure 1.12.

Figure 1.13.

Consider, as one example, their solution of what we would write as the simple linear equation ax = bc. The Greek approach is encapsulated in Propositions 8 and 9 in Book VI of The Elements but is more easily dealt with by using modern algebraic notation. In figure 1.12 a line AX is drawn with points B and C marked on it distant a and a + c units from A respectively. At some convenient angle to AX a line AY is then drawn with a point E marked on it, distant b units from A; the line BE is then drawn and the line through C parallel to this constructed, intersecting AY at D: the length DE is the value for x.

The modern way of looking at the procedure is to notice that ACD and ABE are similar and so

which means that ax = bc.

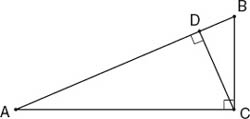

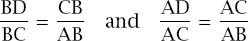

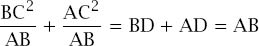

And, as a second example, consider figure 1.13. It is a right-angled triangle ABC with the perpendicular from C meeting AB at D, a construction which gives rise to three similar right-angled triangles. Taking the triangles in corresponding order (ABC, ACD and CBD) and using similarity we have

Therefore,

and so

BC2 + AC2 = AB2.

As we have already mentioned, it is not known what method (if any) Pythagoras or the Pythagoreans used to prove the famous theorem, but one thing is certain: if they used a simple similarity argument, the discovery of incommensurability would have dealt a devastating blow.

It would take an outstanding insight from one of the greatest thinkers of ancient Greece to deal properly with incommensurable magnitudes and so rescue similarity and thereby the geometric method.

Euclid and Systemization

The influence of The Elements in the history of mathematics, in both positive and negative senses, has already been mentioned. Its thirteen “books” constitute the definitive rationalization of the Greek mathematics that had been studied up to its time, both its geometry and also its number theory, and generally there is much confidence in the integrity of the material that has been passed down to us, although the routes it has taken have been long and tortuous.

Unfortunately, such assurance rapidly dissipates when we ask about Euclid himself, about whom almost nothing is known with any certainty. It is true that various ancient authors mention him but without the credibility that is attached to Proclus. We quote again from The Summary:

Not much younger than these [pupils of Plato] is Euclid, who put together the “Elements”, arranging in order many of Eudoxus’s theorems, perfecting many of Theaetetus’s, and also bringing to irrefutable demonstration the things which had been only loosely proved by his predecessors. This man lived in the time of the first Ptolemy; for Archimedes, who followed closely upon the first Ptolemy makes mention of Euclid, and further they say that Ptolemy once asked him if there were a shorter way to study geometry than The Elements, to which he replied that there was no royal road to geometry. He is therefore younger than Plato’s circle, but older than Eratosthenes and Archimedes; for these were contemporaries, as Eratosthenes somewhere says. In his aim he was a Platonist, being in sympathy with this philosophy, whence he made the end of the whole “Elements” the construction of the so-called Platonic figures.

To this we may add the conviction that he taught at Ptolemy’s great university at Alexandria, that The Elements was written around 320 B.C.E. and that mention of him by a modern author adds a little deductive colour29:

In short, it is almost impossible to refute an assertion that The Elements is the work of an insufferable pedant and martinet.

And it is to The Elements that we must look for evidence of progress in the understanding of irrationality and for that purpose we must concentrate on Books V and X: Book V, the accredited work of Eudoxus of Cnidus (as is Book XII); Book X that of the already mentioned Theaetetus. It is with Euclid’s systemization of the work of Eudoxus that we shall start.

If Archimedes of Syracuse (287–212 B.C.E.) was the greatest mathematician of antiquity, surely Eudoxus of Cnidus (408–355 B.C.E.) is runner-up, even though he is primarily acclaimed for his studies in astronomy. None of his original work survives but we do have the supportive witness of (among others) Diogenes Laertius, Proclus and of Archimedes himself, and perhaps the reader will consider it testament enough that two definitions from Books V combine to dispose of the Pythagorean problems with incommensurability in a manner so prescient that the eighteenth-century German mathematician Richard Dedekind was to adapt them in his own definition of irrational numbers, as we shall see in chapter 9. Some of the material which appears is truly remarkable, as it is difficult to understand at a first attempt, a point clearly appreciated by the distinguished nineteenth-century British mathematician Augustus De Morgan in the preface to his own book dedicated to its explanation30:

Geometry cannot proceed very far without arithmetic, and the connexion was first made by Euclid in his Fifth Book, which is so difficult a speculation, that it is either omitted, or not understood by those who read it for the first time. And yet this same book, and the logic of Aristotle, are the two most unobjectionable and unassailable treatises which ever were written.

Our aim is not so grand as to understand the whole book but to demonstrate how Euclid presents the Eudoxian approach to incommensurability and how this approach deals so effectively with the problems brought about by it; to achieve this we will need none of the Book’s 25 propositions and just two of its 18 definitions, together with several propositions taken from Books I and VI.

The Axiom of Eudoxus (attributed to him by Archimedes)

Definition 4, Book V

Magnitudes are said to have a ratio to one another which is capable, when a multiple of either may exceed the other.

Here we should interpret ‘is capable’ to mean ‘makes sense’ and initially the definition seems vacuous; surely it is possible for some sufficiently large multiple of any small magnitude to exceed the larger? Not so. First consider an attempted comparison between a finite straight line and an infinite one; no multiple can be found that causes the finite line segment to be increased to exceed the whole line. Second, the definition also precludes attempting to form the ratio of incomparable quantities; for example, a length and an area. Last, and much more subtly, Eudoxus knew of the concept of what has become known as a Horn Angle, that is, the angle between a straight line and a curve, as shown in figure 1.14. Euclid records the concept, if not by name, then by its nature in

Figure 1.14.

Proposition 16, Book III

The straight line drawn at right angles to the diameter of a circle from its end will fall outside the circle, and into the space between the straight line and the circumference another straight line cannot be interposed, further the angle of the semicircle is greater, and the remaining angle less, than any acute rectilinear angle.

The final, italicized phrase has it that a horn angle is less than any rectilinear angle; hence no multiple of the magnitude of a horn angle is greater than that of a rectilinear angle, and again the definition has bite; infinitesimals are thereby obliquely touched upon. In a few lines the teeth of Definition 4 will close to significant effect. With it we have a device which allows comparison between any pair of numbers, commensurables or incommensurables, without ever mentioning the terms and using only integers. For example, the numbers  and

and  may be compared as a ratio since provably

may be compared as a ratio since provably  >

>  and 2

and 2 >

>  ; similarly, we may compare commensurable with incommensurable numbers: 2 and

; similarly, we may compare commensurable with incommensurable numbers: 2 and  for example; clearly 2 >

for example; clearly 2 >  and also 2

and also 2 > 2.

> 2.

So, we have a meaning for the ratio of any two comparable numbers. Now we look to the succeeding definition wherein Eudoxus shows utterly overwhelming insight as he sweeps aside all problems associated with incommensurability – by ignoring it. What follows is his definition of the ratio of any two magnitudes, incommensurable or not; a definition that allowed Greek geometry to move forward after a century of stagnation in the mire of incommensurability:

Definition 5, Book V

Magnitudes are said to be in the same ratio, the first to the second and the third to the fourth, when, if any equimultiples whatever are taken of the first and third, and any equimultiples whatever of the second and fourth, the former equimultiples alike exceed, are alike equal to, or alike fall short of, the latter equimultiples respectively taken in corresponding order.

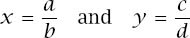

The wording is initially confusing but can be made clearer with the use of a little modern-day algebra, in which case he is saying that (implicitly for magnitudes which can be compared, as in Definition 4 above) the ratio a:b = c:d pertains if for all positive integers m and n:

if na > mb then nc > md,

if na = mb then nc = md,

if na < mb then nc < md.

And this is perhaps made the more reasonable if we build up to it as follows:

For real numbers x and y we can define equality x = y between them by the expedient use of positive integers, arguing that, for all positive integers m and n:

So, x = y if for all positive integers m and n:

if nx > m then ny > m,

if nx = m then ny = m,

if nx < m then ny < m.

Now write

for any real numbers a, b, c, d. Then

if for all positive integers m and n:

which of course leads to

if na > mb then nc > md,

if na = mb then nc = md,

if na < mb then nc < md.

Notice that, although it is necessary for a and b to be magnitudes of the same kind and also for c and d to be so, these two kinds need not be the same; for example, a and b might be lengths and c and d areas.

And the Axiom of Eudoxus can be further used here, since it can be shown to render the middle condition above irrelevant, leaving only the inequalities, and further that these can be combined in the following satisfying way31:

Two ratios are equal when no rational fraction whatever lies between them.

Let us briefly compare the two types of proof, the one using commensurability, the other the approach of Eudoxus. To do so consider:

Proposition 1, Book VI

Triangles and parallelograms which are under the same height are to one another as their bases.

If we concentrate on triangles, this states that the ratio of the areas of two triangles of the same height is the ratio of their bases. Both proofs rely on an earlier proposition, not affected by commensurability issues.

Figure 1.15.

Figure 1.16.

Proposition 38, Book I

Triangles which are on equal bases and in the same parallels equal one another.

That is, triangles having the same base and height are of equal area.

First, let us consider a proof of Proposition 1 based on commensurability.

If the triangles are ABC and AXY, as in figure 1.15, since BC and XY are commensurable there is a common unit u which measures them both; suppose that BC = nu and that XY = mu. On each base mark off the n and m equal length segments respectively and join to A to form n and m triangles respectively, each having a common altitude and equal base. Then ΔABC has been divided into n triangles each of equal area and ΔAXY into m triangles each equal to that same area. Therefore, ΔABC:ΔAXY = n:m = BC:XY.

And now consider one where commensurability is not assumed.

Let the two triangles in question be once again ABC and AXY. Referring to figure 1.16, on CB extended, for arbitrary positive integers m and n, mark off m equal segments and connect to A: similarly on XY extended mark off n equal segments and connect to A. Then Bm−1C = mBC and ΔABm−1C = mΔABC and XYn = nXY and ΔAXYn = nΔAXY. If we adopt the symbol >=< to summarize the triple Eudoxian condition, we have ΔABmC >=< ΔAXYn according as BmC >=< XYn and mΔABC >=< nΔAXY according as mBC >=< nXY for all positive integers m and n.

Therefore ΔABC:ΔAXY = BC:XY as the proposition required. No mention of commensurability of lengths: no integer ratios.

Finally, if we are to gauge the importance of the impact of incommensurability, with its concomitant that any result depending on similarity was doomed, we should look to Pythagoras’s Theorem itself. We have seen the earlier, neat derivation, which does rely on similarity, but in The Elements Euclid has the result appear (as ever, without attribution) as Proposition 47 of Book 1, with his systematization requiring it for a number of other propositions throughout the work, starting in Book 2; all of this long before the Eudoxian approach of Book V. He needed it, he couldn’t prove it using any ideas of similarity and so he provided the famous bride’s chair argument, which has been attributed (by Proclus and others) to Euclid himself. We take the opportunity remind the reader of its comparatively involved detail.

Proposition 47, Book 1

In right-angled triangles the square on the side opposite the right angle equals the sum of the squares on the sides containing the right angle.

The bride’s chair is shown in figure 1.17, with the argument proceeding as follows.

Describe the square BDEC on BC, and the squares BFGA and AHKC on BA and AC. Draw AL through A parallel to BD, and join AD and FC.

Since each of the angles BAC and BAG is a right angle, CA is in a straight line with AG.

For the same reason BA is also in a straight line with AH.

The angle DBA equals the angle FBC, since each has angle ABC common with the remainder of each a right angle.

Since BD equals BC, and BF equals BA, the two sides AB and BD equal the two sides FB and BC respectively, and the angle ABD equals the angle FBC, therefore the base AD equals the base FC, and the triangle ABD equals the triangle FBC.

Figure 1.17.

Now the rectangle BL is double the triangle ABD, for they have the same base BD and are in the same parallels BD and AL. And the square BFGA is double the triangle FBC, for they again have the same base FB and are in the same parallels FB and GC.

Therefore the rectangle BL also equals the square BFGA.

Similarly, if AE and BK are joined, the rectangle CL can also be proved equal to the square ACKH. Therefore the whole square BDEC equals the sum of the two squares BFGA and ACKH.

And the square BDEC is described on BC, and the squares BFGA and ACKH on BA and AC.

Therefore the square on BC equals the sum of the squares on BA and AC.

Therefore in right-angled triangles the square on the side opposite the right angle equals the sum of the squares on the sides containing the right angle.

Clever, but in terms of effort involved, a heavy price to pay to have the result available before its time; if we look to Book V1, the result is generalized as Proposition 31 by having rectangles on each of the sides of the right-angled triangle – and the proof is based on similarity!

With incommensurability of magnitudes acknowledged and tamed, we move to Book X, by far the longest (it constitutes about one quarter of The Elements) and the most challenging of the thirteen books, and the one devoted to summarizing the arithmetic of incommensurables.

Reactions to the work are varied, with Augustus De Morgan saying of it that ‘this book has a completeness which none of the others (not even the fifth) can boast of’, Sir Thomas Heath that Book X ‘is perhaps the most remarkable, as it is the most perfect in form, of all the Books of The Elements’, to be balanced by the view of the one of the twentieth-century’s most distinguished historians of ancient mathematics, the late and greatly lamented Stanford academic, Wilbur Knorr (who also contributed to the study of the Spiral of Theodorus32):

The student who approaches Euclid’s Book X in the hope that its length and obscurity conceal mathematical treasures is likely to be disappointed. As we have seen, the mathematical ideas are few and capable of far more perspicuous exposition than is given them here. The true merit of Book X, and I believe it is no small one, lies in its being a unique specimen of a fully elaborated deductive system of the sort that the ancient philosophies of mathematics consistently prized. It constitutes the results of a detailed academic exercise to codify the forms of the solutions of a specific geometric problem and to demonstrate a basic set of properties of the lines determined in these solutions. One can thus profitably study Book X to learn how its author sought to convert a body of geometric findings into a system of mathematical knowledge.

It is fortunate that scholars have access to a reliable copy (originally in Arabic) of the Commentary of Pappus on the work and it is with his authority33 that the name of Theaetetus is associated with it.

Our purposes will be served by noting the underpinning first four definitions and following them with the first few of a long sequence of propositions:

Definition 1, Book X

Those magnitudes are said to be commensurable which are measured by the same measure, and those incommensurable which cannot have any common measure.

The inevitability of the existence of incommensurable magnitudes is acknowledged.

Definition 2, Book X

Straight lines are commensurable in square when the squares on them are measured by the same area, and incommensurable in square when the squares on them cannot possibly have any area as a common measure.

The distinction is made between two types of incommensurables: those which, although incommensurable in themselves, are commensurable in square and those which are not. The notion distinguishes, for example, between  and

and  =

=  (1 +

(1 +  );

);  is commensurable in square with the unit since (

is commensurable in square with the unit since ( )2 = 2 but

)2 = 2 but  not so since

not so since  2 =

2 =  + 1 (see page 5).

+ 1 (see page 5).

Definition 3, Book X

With these hypotheses, it is proved that there exist straight lines infinite in multitude which are commensurable and incommensurable respectively, some in length only, and others in square also, with an assigned straight line. Let then the assigned straight line be called rational, and those straight lines which are commensurable with it, whether in length and in square, or in square only, rational, but those that are incommensurable with it irrational.

Definition 4, Book X

And let the square on the assigned straight line be called rational, and those areas which are commensurable with it rational, but those which are incommensurable with it irrational, and the straight lines which produce them irrational, that is, in case the areas are squares, the sides themselves, but in case they are any other rectilineal figures, the straight lines on which are described squares equal to them.

With these definitions we see that both incommensurables and commensurables are each infinite in number, if a little confusing.

Next, another contribution from Eudoxus:

Eudoxus’s Method of Exhaustion

Proposition 1, Book X

Two unequal magnitudes being set out, if from the greater there is subtracted a magnitude greater than its half, and from that which is left a magnitude greater than its half, and if this process is repeated continually, then there will be left some magnitude less than the lesser magnitude set out.

Rather than reproduce the original proof from The Elements, we will demonstrate an equivalent, which demonstrates another use of the Axiom of Eudoxus.

Suppose that we have the greater magnitude AB and the lesser CD, then the axiom tells us that there is a positive integer m such that mCD > AB, which means that CD:AB > 1 : m. It is also clear that there is a positive integer n such that 2n > m. Therefore there is an n such that CD:AB > 1 : 2n, which means that (1/2n)AB < CD, with the left-hand side of this inequality an upper bound for the length remaining after the nth cut-off of AB. Therefore, that magnitude is less than CD, as required.

Again, the force of the result may not be apparent at first, but that magnitude CD can be chosen to be as small as we wish; in modern notation we might well choose the letter ε to represent it and with that choice we are easily led to a modern refrain:

. . . given ε > 0 there exists an integer n so that {such-and-such a quantity depending on n} is less that ε . . .

and we have a limiting process which, in the right hands, can be put to extraordinary use. For example, in a letter to his frequent correspondent Eratosthenes, Archimedes himself records that, using this technique, Eudoxus was the first to prove that the volume of the cone and the pyramid are one-third respectively of the cylinder and prism with the same base and height; a result that was known to Democritus but one which he could not establish in a rigorous way. Archimedes was to develop the technique to bring about a host of important and impressive results of quadrature, presaging integral calculus by about 2000 years.

Now we turn to the subsequent proposition, which gives a criterion for incommensurability, although its general usefulness is open to question: when does ‘never’ happen?

If, when the lesser of two unequal magnitudes is continually subtracted in turn from the greater that which is left never measures the one before it, then the two magnitudes are incommensurable.

And then to a short sequence of propositions which characterize commensurability:

Proposition 5

Commensurable magnitudes have to one another the ratio which a number has to a number.

Proposition 6

If two magnitudes have to one another the ratio which a number has to a number, then the magnitudes are commensurable.

Proposition 7

Incommensurable magnitudes do not have to one another the ratio which a number has to a number.

Proposition 8

If two magnitudes do not have to one another the ratio which a number has to a number, then the magnitudes are incommensurable.

With commensurability so defined, later we find an initially bewildering list of differing incommensurables, generated from two given magnitudes a and b which in themselves are incommensurable but which are commensurable in square: their medial is the mean proportion (geometric mean)  , their binomial a+b and their apotome a − b (with a > b). Once again, referring to Pappus

, their binomial a+b and their apotome a − b (with a > b). Once again, referring to Pappus