Does Irrationality Matter?

If the ratio of the circumference of a circle to its diameter be written to thirty five places of decimals, the result will give the whole circumference of the visible universe without an error as great as the minutest length visible in the most powerful microscope

Simon Newcomb (1835–1909)

The opening quotation is taken from Newcomb’s 1882 book Logarithmic and Other Mathematical Tables: With Examples of Their Use and Hints on the Art of Computation. Microscopes have become a great deal more powerful than those available to him and so have telescopes and in consequence we would need to increase that number of decimal places considerably for his statement now to hold true. Yet true it would then be and, moreover, he declared that ‘for most practical applications’ five-figure accuracy is quite sufficient. For the man whose shared logarithmic tables used at the Nautical Almanac Office alerted him to what is now known as Benford’s Law, π = 3.14159.

Practical Matters

From the very lengthy lists of formulae involving π and e let us select four from each:

• The Cauchy distribution has a density function φ(x) = 1/π(1 + x2).

• The probability that two randomly chosen integers are coprime is 6/π2.

• The period of a simple pendulum is

• Einstein’s field equations are

Rik − gikR/2 + Λgik = (8πG/c4)Tik.

• The logarithmic spiral has polar equation r = eaθ.

• The catenery has Cartesian equation y = (ex + e−x)/2.

• The damped harmonic oscillator is governed by the equation x = e−t cos(ωt + α).

• The Poisson distribution has density function φ(k) = e−λλk/k!.

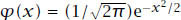

And then there is the density function of the normal distribution,  which conveniently involves all three of our standard irrational triplet of π, e and

which conveniently involves all three of our standard irrational triplet of π, e and  .

.

The theoretical derivation of every one of these formulae, and all besides, leads to the appearance of some fundamental constant(s): π, e and  are three such. They appear as exact numbers and so it is as well that we have symbols for them, but it is quite irrelevant that they are irrational. For all practical applications any awkward constant that appears in a formula can be approximated as necessary so that the theoretical formula is utilized to help with a problem of the real world, with a well-known mathematical ‘joke’ putting matters into a light-hearted perspective:

are three such. They appear as exact numbers and so it is as well that we have symbols for them, but it is quite irrelevant that they are irrational. For all practical applications any awkward constant that appears in a formula can be approximated as necessary so that the theoretical formula is utilized to help with a problem of the real world, with a well-known mathematical ‘joke’ putting matters into a light-hearted perspective:

What is π?

A mathematician: π is the ratio of the circumference of a circle to its diameter.

A computer programmer: π is 3.141592653589 in double precision.

A physicist: π is 3.14159 plus or minus 0.000005.

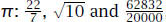

An engineer: π is about 22/7.

A nutritionist: pie is a healthy and delicious dessert.

In chapter 2 we mentioned the skill demonstrated by the Hindus and Arabs in manipulating surds but their ability to approximate was equally impressive. The astronomer and mathematician Al-Khwārizmī, whom we mentioned there, used the three approximations to  where he described the first as an approximate value, the second as used by geometricians and the third as used by astronomers. The values were not new with all of them, and many more besides, originating with the Hindus and reaching the Arabs through translations of works; this mysterious last value, impressively accurate to four decimal places, seems to have originated with the Hindu polymath Aryabhata 1 (476–550 C.E.) and is found in his work Aryabhatiyam:

where he described the first as an approximate value, the second as used by geometricians and the third as used by astronomers. The values were not new with all of them, and many more besides, originating with the Hindus and reaching the Arabs through translations of works; this mysterious last value, impressively accurate to four decimal places, seems to have originated with the Hindu polymath Aryabhata 1 (476–550 C.E.) and is found in his work Aryabhatiyam:

8 times 100 increased by 4 and 62 of 1000s is an approximate circumference of a circle diameter 20,0001

which makes  Quite how he came about the approximation is a mystery.

Quite how he came about the approximation is a mystery.

Throughout millennia, with the Greeks and their predecessors, long before the Hindus and Arabs and long after them, methods to approximate irrational numbers have tested the ingenuity of the scientist, with each new equation bringing with it its own requirements for sensible application. Let us take a contemporary example: if we refer to the Universal Constants page of the website of the National Institute of Standards and Technology2 we find a table, one entry of which is the permeability of free space µ0, otherwise known as the magnetic constant, which has a defined value of exactly 4π × 107 NA−2. The value then ascribed to the constant for purposes of calculation is 12.566370614 . . . × 107, which means that, in this case, 3.1415926533  π < 3.1415926536.

π < 3.1415926536.

Now move to and its involvement in the well-tempered musical scale. This twentieth-century division of the musical scale has the octave defined as the interval between a note and a second of twice its frequency. This frequency interval is divided into 12 subintervals (semitones) between (say) C and the c above with the frequency of c double that of C. The scheme is coded in musical terms as follows:

and its involvement in the well-tempered musical scale. This twentieth-century division of the musical scale has the octave defined as the interval between a note and a second of twice its frequency. This frequency interval is divided into 12 subintervals (semitones) between (say) C and the c above with the frequency of c double that of C. The scheme is coded in musical terms as follows:

A, A#, B, C, C#, D, D#, E, F, F#, G, G#.

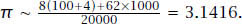

The well-tempered scale is defined to have the frequency of the next A to the right of middle C at exactly 435 Hz, which means that the frequencies of the subsequent notes in the octave are

And we have a collection of eleven irrational multiples with the standard accuracy of two decimal places giving the values

(435, 460.87, 488.27, 517.31, 548.07, 580.67, 615.18, 651.76, 690.52, 731.58, 775.08, 821.17, 870).

With this accepted standard of useful accuracy, if our approximation to 21/12 is written as T the most testing requirement is that 821.165 < T11 × 435 < 821.175 and this makes

1.05946243 < T < 1.05946326.

Since 21/12 = 1.059463094 . . . we can safely use the approximation T = 1.059463 and six decimal places is sufficient for purpose.

And finally let us move to the Golden Ratio, φ = (−1 +  )/2. It is commonly held that rectangles of dimension 1 × φ are aesthetically pleasing and that this harmony has been exploited by architects and artists from antiquity to the present day. Yet, it is hard to imagine visiting the artist or the architect with a calculating task more challenging than φ ~ 1.6 and 1/φ ~ 0.6: the Parthenon will not fall as a result or the Mona Lisa look less beautiful. More demanding of precision is the use of φ in speaker cabinet design. It is agreed by experts that a simple cuboidal speaker will have its undesirable internal standing waves significantly diminished if its dimensions are in the ratio 1/φ : 1 : φ. Let us see what an expert3 advises on the optimal dimensions for a speaker of volume 4 cubic feet:

)/2. It is commonly held that rectangles of dimension 1 × φ are aesthetically pleasing and that this harmony has been exploited by architects and artists from antiquity to the present day. Yet, it is hard to imagine visiting the artist or the architect with a calculating task more challenging than φ ~ 1.6 and 1/φ ~ 0.6: the Parthenon will not fall as a result or the Mona Lisa look less beautiful. More demanding of precision is the use of φ in speaker cabinet design. It is agreed by experts that a simple cuboidal speaker will have its undesirable internal standing waves significantly diminished if its dimensions are in the ratio 1/φ : 1 : φ. Let us see what an expert3 advises on the optimal dimensions for a speaker of volume 4 cubic feet:

First, take the desired enclosure volume and convert it into a more precise (‘working’) unit of measurement − in your case inches. 1 cubic foot equals 1728 cubic inches; therefore 4 cubic feet equals 6912 cubic inches.

Next, take the cubed root of the total volume, 6912 cubic inches. The result becomes the basic working dimension of the enclosure. For a 6912 cubic inch enclosure this will be 19.0488 inches.

Now take 19.0488 inches and multiply it by the quantity (−1 +  )/2, or 0.6180339887, and you will obtain one of the other ‘optimum’ dimensions, which should be 11.7728 inches for the smallest internal dimension for your enclosure.

)/2, or 0.6180339887, and you will obtain one of the other ‘optimum’ dimensions, which should be 11.7728 inches for the smallest internal dimension for your enclosure.

Finally, take the initial 19.0488 inch result and multiply it by the quantity (− 1 +  )/2, or 1.6180339887, and you will obtain the remaining optimum dimension, which should be 30.8216 inches for the largest internal dimension for your enclosure.

)/2, or 1.6180339887, and you will obtain the remaining optimum dimension, which should be 30.8216 inches for the largest internal dimension for your enclosure.

If you wish to verify the validity of your calculations simply multiply the three results together and you should obtain almost exactly the original enclosure volume. Thus, (11.7728 in.)(19.0488 in.)(30.8216 in.) = 6911.9993 in.3 approximately. Again, I have to emphasize that it is very important to remember that all of the dimensions above are INTERNAL enclosure dimensions.

And so we have the optimal dimensions, each to four decimal places. But then, the advice finishes with the statement:

Also please note that if you prefer you can safely round each of the derived dimensions to the nearest half-inch (0.50 in.) without incurring any detrimental consequences.

So, in the end the optimum dimensions of the loudspeaker box are 12 × 19 × 31 inches.

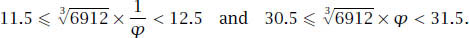

With such a final tolerance the accuracy required is determined by the two double inequalities:

To manipulate these to bounds for φ we will use the full accuracy that a standard calculator gives for the cube root of the volume to see that

1.5239 < φ < 1.6564 and 1.6011 < φ < 1.6536.

The second condition is, of course, the stronger and so we may take the value of φ to be anything in the interval 1.6011 < φ < 1.6536. Removing the awkward volume and replacing it with a more convenient one of, say, 1000 units a recalculation yields the interval 1.55 < φ < 1.65. So, it seems that φ ~ 1.61 would do nicely. When the author asked a friend who is a sound engineer what value would be taken as φ in his own calculations the immediate response was 1.618, which seems to make a great deal of sense.

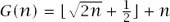

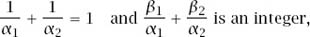

Figure 11.1.

Irrationality is quite irrelevant, then: now we will consider the other case, where it is crucial.

Theoretical Matters

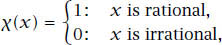

With the definition of the function χ(x),

it is hardly surprising that the rationality or otherwise of a number is of crucial importance. What may be surprising is the observation that the function given on page 8 is an analytic representation of it, with

As such it is an indicator function for the (ir)rational numbers and a shocking example of an infinite sequence of functions the (double) limit of which is everywhere discontinuous.

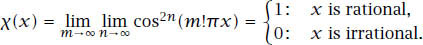

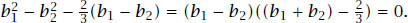

It seems that Dirichlet was the first to consider such a pathology and it seems also that it was the German Carl Thomae who amended it to

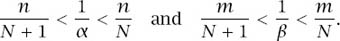

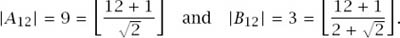

This Thomae (Popcorn, Star over Babylon, etc.) function, shown in figure 11.1, also has an obvious dependency on (ir)rationality and a rather less obvious consequence of this dependency is that it is continuous at all irrational numbers and discontinuous at all rational numbers.

Figure 11.2.

The informal demonstration of the fact is pleasant and uses an observation from chapter 6: if we want to approximate a real number arbitrarily closely by rational numbers, the denominators of those irrational numbers must grow arbitrarily large. With this reminder, suppose that x is irrational and so f(x) = 0. If x1 is arbitrarily close to x then x1 is either irrational, in which case f(x1) = 0, or rational, in which case f(x1) ~ 0 since its denominator will be arbitrarily large. These combine to f(x) being continuous at irrational values for x. On the other hand, suppose that x is rational, then again the arbitrarily close point x1 is either irrational and so f(x1) = 0 or rational and so f(x1) ~ 0 and these are not arbitrarily close to f(x) = 1/q.

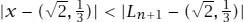

The dependency on irrationality is more subtle with the version of the Penrose Tiles consisting of the dart and the kite, as shown in figure 11.2. These form an aperiodic tiling of the plane only because the Golden Ratio is irrational, otherwise the tiling would be periodic.

Now consider three results from the study of dynamical systems, which are often framed in terms of a circle:

Take a circle C of circumference 1 unit, choose any real number α and repeatedly shift each point (say anticlockwise) on the circle by α, measured as a distance along the circumference. With this, every point will orbit the circle indefinitely, but in a manner depending on whether α is rational or irrational:

If α = p/q in lowest terms is rational the orbit of every point will be closed, repeating itself after q iterations.

If α is irrational the whole process is far more complex, with these results referring to the orbit of any point on the circle:

1. The orbits ‘exhaust the circle’ in that, if we take any point on the circle there is an infinite subsequence of the orbit which converges to the point.

2. For any arc of length l on the circle, the asymptotic fraction of points in the orbit which are contained in the arc is precisely l.

3. If we truncate the orbit to a finite set of points, these points divide the circle into intervals of at most three different lengths and if there are three different lengths the largest is the sum of the other two.

In fact, that first result was foretold by Nicole Oresme, whom we first met in chapter 2 attempting to use irrational numbers to dismantle the uncomfortable idea of the Perfect Year. In Proposition II.4 of his work, Tractatus de commensurabilitate vel incommensurabilitate motuum celi,4 he made the following comment regarding two bodies moving in a circle with uniform but incommensurable velocities:

No sector of a circle is so small that two such mobiles could not conjunct in it at some future time and could not have conjuncted in it sometime (in the past).

We could continue with such results but will choose to move to three cases where irrationality is crucial. In the first two they appear in a manner reminiscent of the role of complex numbers when they are used to prove results about the reals: they appear, solve the problem and disappear; rather like a mathematical fairy godmother. In the third case there is a geometric result of no little interest.

Waclaw Sierpiński’s rather cryptic response to a question posed in 1957 by Hugo Steinhaus was this: the point ( ,

,  ) has different distances from all points of the plane lattice.5

) has different distances from all points of the plane lattice.5

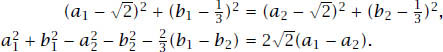

Suppose that, with integer coordinates, there are two points (a1, b1) and (a2, b2) that are equidistant from ( ,

,  ). Then

). Then

The left side is rational and the right irrational unless a1 = a2 and this makes the left side 0. So,

and, using a1 = a2,

Since the two points are assumed distinct and since the first coordinates are already proved to be the same, b1 ≠ b2, and therefore

(b1 + b2) −  = 0,

= 0,

which is impossible since b1, b2 are integers.

Steinhaus’s question initially seems remote from Sierpiński’s answer, since it was: For any positive integer n, does there exist a circle which contains precisely n points having integer coordinates?

The emphasis is with the condition that there should be precisely n points and the answer is yes and is found in the following pleasant argument.

We have seen that Cantor had long before proved that the integers  and the plane lattice points

and the plane lattice points  ×

×  are each countable. We have already noted that this means that the sets can be listed, so let us list the points of the plane lattice as

are each countable. We have already noted that this means that the sets can be listed, so let us list the points of the plane lattice as

×

×  = {L1, L2, L3, . . .},

= {L1, L2, L3, . . .},

where the ordering is by increasing distance from the point ( ,

,  ). Then,

). Then,

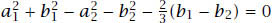

defines a circular disc centre ( ,

,  ) and radius |Ln+1 − (

) and radius |Ln+1 − ( ,

,  ) |, which contains precisely the points L1, L2, L3, . . . , Ln.

) |, which contains precisely the points L1, L2, L3, . . . , Ln.

Our second example requires a more lengthy discussion. Take the positive integers and divide them into two infinite, non-empty, non-overlapping subsets. These subsets may have structure or not: if one is the set of prime numbers and the other the set of composite numbers there is structure but no pattern, with one the set of even numbers and the other odd numbers there is both and with one a random selection there is neither. We will look at a case where there is clear structure which sometimes gives rise to a pattern and at other times not.

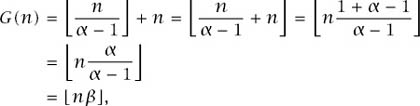

In the 1877 book The Theory of Sound authored by the eminent mathematical physicist John Strutt, 3rd Baron Rayleigh (Lord Rayleigh), we find an observation made by him in the study of the harmonics of a vibrating string which can naturally be framed in purely mathematical terms in terms of irrational numbers. Independently rediscovered by the American mathematician Samuel Beatty,6 it appeared in the problems column of the American Mathematical Monthly in the words:

3173. Proposed by Samuel Beatty, University of Toronto.

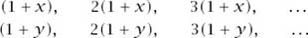

If x is a positive irrational number and y its reciprocal, prove that the sequences

contain one and only one number between each pair of consecutive positive integers.

Solutions were published in the journal in March of the following year7 and the problem was resurrected in 1959 as Problem A6 of that year’s Putnam competition8 in a slightly revised form:

Show that, if x and y are positive irrationals such that 1/x + 1/y = 1 then the sequence  x

x ,

,  2x

2x , . . .

, . . .  nx

nx , . . . and

, . . . and  y

y ,

,  2y

2y , . . .

, . . .  ny

ny , . . . together include every positive integer exactly once.9

, . . . together include every positive integer exactly once.9

And it is this form that we shall study the phenomenon.

First notice that a rational value for x will not do: write x = p/q, where p > q (since x > 1), then a common term will be reached when  (p/q)n

(p/q)n =

=  (p/(p − q))m

(p/(p − q))m and with n = q and m = p − q or multiples thereof the common integer p and its multiples are generated.

and with n = q and m = p − q or multiples thereof the common integer p and its multiples are generated.

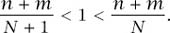

Before we consider the matter, let us restate it as:

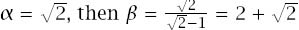

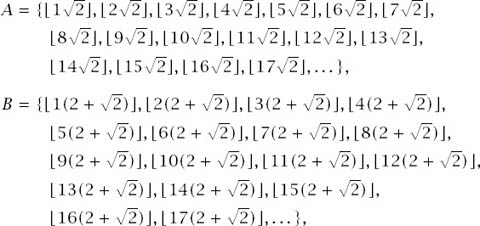

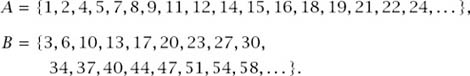

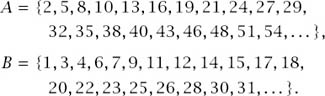

Let α be a positive irrational number, define the irrational number β by 1/α + 1/β = 1 and the two sets A and B by

A = { nα

nα : n = 1, 2, 3, . . .} and B = {

: n = 1, 2, 3, . . .} and B = { nβ

nβ : n = 1, 2, 3, . . .}.

: n = 1, 2, 3, . . .}.

Then:

If this is the case we should note that the two sequences A and B are termed complementary.

We know that irrationality is necessary for the result to hold, before we show that it is sufficient let us develop a feel for the process by considering these four examples.

Take  and we have

and we have

which simplify to

Similarly, if α = π, the sequences are

And if α = e they are

Lastly, and provocatively, if α = γ + 110

With these suggesting the truth of the result, we shall go about proving it.

First we prove that A ∩ B =  and to do this let us assume otherwise and presume that the two sequences have an element in common. If this is so, there must exist positive integers m and n so that

and to do this let us assume otherwise and presume that the two sequences have an element in common. If this is so, there must exist positive integers m and n so that  nα

nα =

=  mβ

mβ = N and this means that the two inequalities

= N and this means that the two inequalities

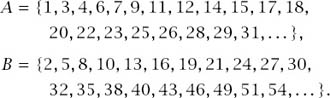

N < nα < N + 1 and N < mβ < N + 1

must simultaneously hold: note the crucial point that the inequalities are strict since α and β are irrational. Rearranging these gives

And using the defining condition

And rearranging this double inequality results in

N < n + m < N + 1,

which tells us that there is an integer m + n lying strictly between the integers N and N + 1 − which is impossible. It must be that A ∩ B =  .

.

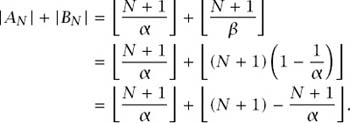

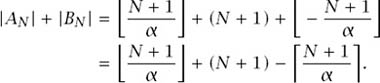

Now consider the two finite sequences, the biggest element of one being N and of the other an integer less than N:

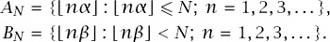

For example, with the  case above and with N = 12,

case above and with N = 12,

A12 = {1, 2, 4, 5, 7, 8, 9, 11, 12} and B12 = {3, 6, 10}.

A little thought reveals that the number of elements in each sequence is calculated as follows:

And, in general,

So, the total number of elements in the two lists is

Now we need two properties of the Floor and Ceiling functions:

M + θ

M + θ = M +

= M +  θ

θ and

and  −θ

−θ = −

= − θ

θ

for M an integer and θ arbitrary. Using these, we have

Since (N + 1)/α cannot be an integer,  (N + 1)/α

(N + 1)/α =

=  (N + 1)/α

(N + 1)/α − 1 and this means that

− 1 and this means that

And we are done: the two sequences combine to the sequence of positive integers {1, 2, 3, . . . , N} for arbitrary N.

Now look back at our four examples. The alert reader will have noticed gaps in the latter portion of A ∪ B since we are constrained by the inevitable stopping point in the lists A and B: much more than this, we are condemned to use a rational approximation to the numbers to generate the lists. In short, we can prove the result but never realize it.

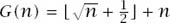

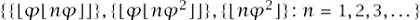

Let us look finally at a more general construction which separates the positive integers.

In 1954 two Canadian mathematicians Leo Moser and Joachim (Jim) Lambek established the following result about complementary sequences11:

Let f(n) be a non-decreasing function which maps the natural numbers into itself and define a second function f*(n) = the maximum k for which f(k) < n for each natural number n. Now define two more functions F(n) = f(n) + n and G(n) = f*(n) + n, then the sequences generated by F(n) and G(n) will be complementary.

At first the result is a little slippery to grasp so let us take a particular case, with f(n) = 2n. The process generates the following table:

We can see that the final two rows of the table suggest a partition the natural numbers, with our two sets defined to be

A = {3, 6, 9, 12, 15, 18, 21, . . .}

and

B = {1, 2, 4, 5, 7, 8, 10, . . .}.

The multiples of 3 and the non-multiples of 3.

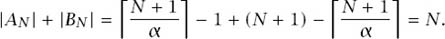

Moreover, we have a simple formula for F(n) = f(n) + n = 2n+n = 3n, which is hardly a surprise. What is much more exiting is that we can also find a compact formula for the B sequence of non-multiples of 3; that is, for the function G(n) = f*(n) + n.

If we look more carefully at the definition of f*, to find its value for any n we need to find the maximum k for which the equation 2k < n holds, that is, k < n/2. This suggests the Floor function with maximum k =  n/2

n/2 , but the inequality is strict and if n were to be even

, but the inequality is strict and if n were to be even  n/2

n/2 = n/2. To combat this and to cope with both cases simultaneously, for odd n the fractional part of n/2 is precisely

= n/2. To combat this and to cope with both cases simultaneously, for odd n the fractional part of n/2 is precisely  and so subtracting (say)

and so subtracting (say)  will not alter matters and will bring the value of the Floor function to its required level. That is, the maximum k =

will not alter matters and will bring the value of the Floor function to its required level. That is, the maximum k =  n/2 −

n/2 −

and so f*(n) =

and so f*(n) =  n/2 −

n/2 −

, which makes

, which makes

G(n) = f*(n) + n =  n/2 −

n/2 −

+ n

+ n

and we have a succinct formula for sequence B and so for all non-multiples of 3. Try it! And afterwards the reader might like to use the same technique12 to show that the nth non-square natural number can be written

and, without hint, the nth non-triangular number

and then move to other possibilities.

Our main interest is that we can frame our earlier result involving irrational numbers in these terms.

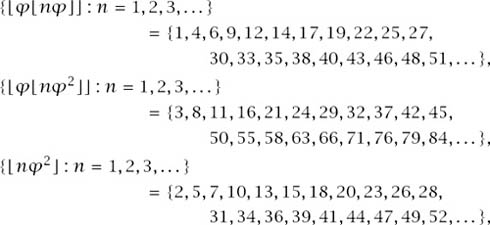

Define

f(n) =  nα

nα − n and so F(n) =

− n and so F(n) =  nα

nα .

.

By its definition, f*(n) = the largest m so that f(m) < n. That is, the largest m so that  mα

mα − m < n and so

− m < n and so  mα − m

mα − m =

=  m(α − 1)

m(α − 1) < n. This in turn means that

< n. This in turn means that  m(α − 1)

m(α − 1) = n − 1 and this means that n − 1 < m(α − 1) < n. Finally, it must therefore be that m is the largest integer so that m < n/(α − 1), which makes m =

= n − 1 and this means that n − 1 < m(α − 1) < n. Finally, it must therefore be that m is the largest integer so that m < n/(α − 1), which makes m =  n/(α − 1)

n/(α − 1) . All of this means that f*(n) =

. All of this means that f*(n) =  n/(α − 1)

n/(α − 1) and this makes

and this makes

where α/(α − 1) = β, or 1/α + 1/β = 1. The reader will identify why the irrationality is important.

Can we separate the positive integers into three or more disjoint, infinite sets using irrational numbers? We cannot, as Aviezri S. Fraenkel has provided a delightful proof of the following result13:

Let m > 1, α1, . . . , αm be positive. Then { nαi

nαi : i = 1, . . . , m; n = 1, 2, . . .} is a complementary system if and only if

: i = 1, . . . , m; n = 1, 2, . . .} is a complementary system if and only if

1. m = 2,

2. 1/α1 + 1/α2 = 1,

3. α1 is irrational.

There are, though, the likes of

or

which has been shown to be complementary by the Norwegian mathematician Thoralf Skolem, who (among other things) has also produced the two-dimensional equivalent, which does not necessarily involve irrational numbers, but when it does so:

If α1 is irrational then {S(α1, β1), S(α2, β2)} form a partition if and only if

where

We will leave the matter of the importance of irrationality on what might be regarded as a negative note: an example wherein it is crucial for a number not to be irrational.

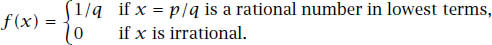

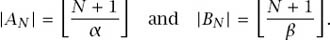

Finally, we shall consider the problem of the dissection of a square into squares (squaring the square), which seems to be one of surprisingly recent vintage. The English puzzle genius Henry Dudeney appears to have been the first to hint at the idea with his Lady Isobel’s Casket problem, which appeared in the Strand Magazine of January 1902. In fact the problem asked for a dissection of a 20 × 20 square into squares and a single 10 ×  rectangle but the idea quickly caught the imagination and results connected with the problem rapidly appeared and are now legion. Our interest is with a contribution of Max Dehn, who, in 1903, proved that a rectangle can be squared if and only if the ratio of its sides is a rational number. Figure 11.3 shows an example of such a squaring and the result a final opportunity for proof.

rectangle but the idea quickly caught the imagination and results connected with the problem rapidly appeared and are now legion. Our interest is with a contribution of Max Dehn, who, in 1903, proved that a rectangle can be squared if and only if the ratio of its sides is a rational number. Figure 11.3 shows an example of such a squaring and the result a final opportunity for proof.

Figure 11.3.

First we show that, if the ratio of the sides of the rectangle is rational, the rectangle can be squared. Actually, it can be tiled as a bathroom floor with squares of side 1 unit. If the sides of the rectangle a × b are both integers the tiling by unit squares is obvious; if a/b = p/q is rational the rectangle is similar to the one with sides qa × qb = pb × qb and can be tiled by squares of side b.

Now suppose that the rectangle is capable of being tiled by squares. We set up a coordinate system with origin the lower left corner of the square and sides the x and y axes and, if it happens that both coordinates of every corner of every square are integers, the side of every square would be an integer and so the sides of the rectangle must be integers.

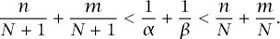

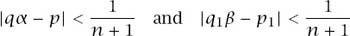

Suppose, then, that this is not and recall this version of Dirichlet’s Approximation Theorem from chapter 6:

Figure 11.4.

Suppose that α is a real number, then for any positive integer n there exist positive integers p and q, with q  n, such that |qα − p| < 1/(n + 1).

n, such that |qα − p| < 1/(n + 1).

That is, a suitable integer multiple of any real number can be made arbitrarily close to some integer.

Suppose, though, that we have two real numbers α and β. Then the result asserts that

for suitable integers, but what is not clear is that it is possible to choose q1 = q for some q; that is, the inequalities can be simultaneously satisfied. Generalizing this to an arbitrary finite number of real numbers brings us to the Dirichlet Simultaneous Approximation Theorem, which tells us that this is possible. We choose not to prove this difficult result but certainly we shall now use it.

We refer to figure 11.4 throughout. Although not all coordinates of all vertices of all squares are integers we invoke the theorem and so multiply each of them by the same integer to create a similar rectangle tessellated by squares of near-integer coordinate vertices. Now draw horizontal lines half a unit apart throughout the rectangle and consider the total length Lh of these lines within the rectangle. First, each component of Lh has length a and there are an integral number na of them, therefore Lh = a × na; similarly, constructing vertical lines results in Lv = b × nb.

Second, we add up the component lengths of Lh by counting the contribution from each square of the tessellation. If the lengths of the sides of the squares are written si then Lh = Σi si × nsi; again we repeat for the vertical lines, and this is where the near integral coordinates comes in. Since the vertices can be made arbitrarily close to integers, no matter what the location of the square in the rectangle, the vertical lines will cross each square exactly the same number of times as the horizontal lines, therefore Lv = Σisi × nsi. This means that Lh = Lv and so a × na = b × nb, which means that a/b = nb/nb is rational.

And with this we are done: our account of irrationality has eventually reached its final page. It has been a tale of long-term struggle, desperate optimism, grudging acceptance, inspired insight and no little controversy. Our twenty-first-century understanding is at once firm and far-reaching, as it is beset with unanswered questions. It is our hope that among this book’s readership there will be one (or more) whose fate it is to carry matters further.

1Victor J. Katz (ed.), 2007, The Mathematics of Egypt, Mesopotamia, China, India and Islam (Princeton University Press).

2physics.nist.gov/cgi-bin/cuu/Category?view=gif&Universal.x=117&Universal.y=10.

3answers.yahoo.com/question/index?qid=20080406124528AAfNJia.

4On the commensurability or incommensurability of the heavenly motions

5The points in the plane with both coordinates integers.

6American Mathematical Monthly, March 1926, Problem 3173, 33(3):159.

7American Mathematical Monthly, March 1927, Solution 3177, 34(3):159–60.

8William Lowell Putnam Mathematical Competition: Problems and Solutions 1938–1964, 1980, Math. Ass. Am., pp. 513–14.

9Where, once more,  ·

·  is the Floor function.

is the Floor function.

10Euler’s Constant, γ = 0.57721 . . . . , the irrationality of which we have remarked remains an open question. Also, we need the number used to be greater than 1.

11J. Lambek and L. Moser, 1954, Inverse and complementary sequences of natural numbers, American Mathematical Monthly 61:454–58.

12This time, start with F(n) = n2.

13Aviezri S. Fraenkel, 1977, Complementary systems of integers, American Mathematical Monthly 84:114–15.