CHAPTER 4

Don’t Just Do It … Just Be It

The question for an introvert is … not why I am such a bad hammer. It is whether I am willing to be happy being an excellent screwdriver … and quietly get on with inserting screws while others enthusiastically attack the nails.

Mark Tanner255

“Just Do It.” The sports apparel company Nike gave us one of the most motivational advertising messages of all time, urging the average American to heave off the couch, lace up a pair of sneakers, and tap into one’s dormant inner athlete. Nike is the Greek goddess of victory, “both in war and in peaceful competition.”256 Archaeologists found an akroterion, an architectural ornament, of the goddess Nike at the Temple of Apollo, the location of the Seven Sages’ inscription: “Know thyself.” The sports brand’s imperative promotes the empowering message that we can accomplish anything to which we set our minds, simply by “just doing it.”

Some well-intentioned mentors prod at introverted, shy, and socially anxious individuals, “Just put yourself out there! Grow a thicker skin! Sell yourself! Just speak up!” Unfortunately, these mantras remind me of the cartoon character from The Simpsons, Troy McClure, an infomercial spokesperson who promotes his self-help videos with the tagline, “Hi, I’m Troy McClure. You might remember me from such self-help videos as ‘Smoke Yourself Thin,’ and ‘Get Confident, Stupid.’”257 Just do it. Get over it. Man up. Get confident, stupid.

We’re not stupid. We’re smart and we’re quiet. We just might need a refreshed perspective on how to amplify our voices authentically when it’s time for the legal world to hear our messages. But because “just do it” is not going to work for us in this context, we need an alternate strategy.258

NEITHER TOTAL AVOIDANCE NOR MINDLESS MASOCHISM IS A VIABLE HOLISTIC SOLUTION

Regrettably, so many of the coping strategies some of us invoke when we are confronted with interpersonal exchanges in the legal context impede rather than foster our growth. Some quiet law students and lawyers become masters in artful dodging and creative avoidance: wielding laptop screens like invisibility cloaks while hiding in the back row of a classroom, taking a “pass” when on-call in the Socratic Method (even if abstention affects a participation grade), bypassing hard-core Socratic-driven electives, choosing transactional law careers (assuming compulsory extemporaneous debate will be minimized) instead of litigation jobs, or hopscotching from case to case within a law office, demurring deposition and trial opportunities to more outgoing colleagues. Drs. Barbara G. Markway, Cheryl N. Carmin, C. Alec Pollard, and Teresa Flynn explain that avoidance behaviors constitute “maladaptive coping”; indeed, evasion “provides temporary relief” but “can quickly become part of the problem. In the long run, such strategies feed your anxiety and keep your fear of disapproval alive.”259 Flowers echoes this principle: “Unfortunately, the very effort to escape thoughts, or even suppress or control them, usually intensifies them.”260

Others adopt the opposite tack; they have been mechanically “just doing it.” They levitate hands in the air to answer Socratic questions while weathering internal punches from thudding hearts. They boldly enroll in trial advocacy courses in a misplaced effort to will the innate resistance or nerves away. They join public speaking groups hoping the rote practice will eliminate natural hesitation or trepidation toward addressing an audience. Despite these admirable and courageous aspirations, this approach still nosedives, and, worse, can trigger or exacerbate interpersonal anxiety. Merely surviving one experience after another, for better or worse, does nothing to address the dissonance between our natural quiet personas and the pressure to orate in the legal arena. Not realizing the potential detrimental repercussions of this brute approach, many teachers, parents, siblings, classmates, significant others, law office mentors, and colleagues continue cheering, “Just do it!”

WHY “JUST DO IT” DOES NOT WORK TO “FIX” QUIET FOLKS

Why exactly don’t rousing slogans like “just do it” and “fake it till you make it” work for quiet individuals in the legal context? First, Drs. Markway, Carmin, et al. convey that well-intentioned quips to hesitant speakers like, “Being nervous just means you care,” or “Just imagine the audience members in their underwear,” can be “trivializing.”261 Telling a quiet law student or lawyer that his or her internal conflict is no big deal demeans the already vulnerable individual and reinforces the feeling of fraudulence: “If this feels so bad to me, and nobody else can relate, maybe I’m not cut out to be a lawyer.”

Second, Flowers explains that the “just do it” approach is rational and logical, while much anxiety toward social or professional interaction stems from emotions and feelings not based in rationality or logic; “[o]ne of the problems with [the ‘doing’] approach is that it’s linear and goal oriented, whereas feelings are neither.”262 (These types of irrational and illogical feelings are, of course, distinguishable from the introvert’s scientifically validated—and rational—resistance toward certain interpersonal scenarios, as described in Chapter 1). Flowers elaborates:

Most people attempt to overcome shyness using rational thought, which isn’t surprising, as this is the mental orientation in which we generally spend most of our time … This is the kind of thinking that enables us to create lifesaving medications or build spacecraft, and it sometimes comes in handy for figuring out where you placed your car keys, but it can cause problems when it’s the only approach you use to manage fear or social anxiety.263

For “just do it” folks valiantly trying to “get over it” as advised by mentors and peers, this pursuit soon takes on the character of punishment—which, well, stings. As Drs. Markway and Markway describe, “We think if we punish ourselves enough, we’ll change.”264 We hurl ourselves into the scary evaluative fray, hoping that one day, the discomfort, self-criticism, or fear of disapproval will vanish. Yet, as Flowers counsels, “As long as you’re looking at yourself from somewhere outside … and trying to perform to what you believe to be the standards of others, you will be judging and striving. You’ll be trapped in doing mode and out of touch with your more authentic, whole self.”265 Instead of scrapping and hustling to adhere to external standards of extroversion, we need to still ourselves and focus inward—where we introverts thrive.

CHANNELING SOCRATES AND THE SEVEN SAGES: GETTING TO KNOW THYSELF

Socrates said, “The unexamined mind is not worth living.”266 Flowers echoes that “[n]othing can cause quite so much trouble as an unexamined mind.”267 Left unexplored, embedded patterns repeat on a loop in our brains, and negative thoughts tighten their grip. Something truly awesome and earth-shattering needs to happen to stop this vicious cycle once and for all, so we can expel our mental detritus.

To tackle introvert discomfort or deeper shame-fueled shyness or social anxiety, we must step back and survey our genetic and environmental landscape. Hesitance toward social engagement in the legal arena likely reflects our personal organic makeup intermingled with our unique combination of life experiences. Many of us have no idea how deeply the roots of our modern-day quietude were seeded through biological facilitators such as “genetics, neurobiology, and temperament,” combined with environmental stimuli such as childhood influences, adult-child dynamics, and other formative undercurrents.268 In addition to our inborn personality trait of introversion, kernels of judgment, criticism, or censorship may have been embedded in some of us ages ago, perhaps inadvertently and naïvely by well-meaning caregivers or mentors, or more nefariously by hurtful critics. We absorbed and internalized these messages. Through repetition, we ossified them into schema of avoidance, self-protection, fear, and doubt. Negative soundbites became part of our mental soundtrack. Now, years later, they replay over and over as we step into our new roles on the legal stage.

Of course, we realize something is off, but we can’t feel better until we pinpoint exactly what hurts. Our unhealthy mental, physical, and behavioral responses to stressful scenarios are automatic and inevitable without thoughtful observance, recognition, reflection, and reframing. That’s why “just do it” doesn’t do anything in this setting. Striding into yet another torturous performance-oriented engagement in the legal arena—without enhanced self-awareness and mindful intent—accomplishes nothing more than repeating the problematic thoughts, feelings, and behaviors, further hardening and fortifying our harmful responses to stress. Dutifully, we throw ourselves into the same fire that we have leapt into many times before, yearning for a different outcome. Albert Einstein is attributed (though writers say the true source cannot be confirmed)269 as saying, “the definition of insanity is doing the same thing over and over again and expecting different results.”

Let’s stop this brand of insanity. Let’s dismount the treadmill-to-nowhere. Instead, let’s study ourselves, become aware of our unhelpful triggers and responses in the legal environment, recognize that our prior habits are malleable, and consciously repurpose our obsolete negative energy into something useful. Let’s “just be it.” Let’s be quiet yet transformative advocates. Caveat: “just be it” does not mean we get to loll around like lotuses, expecting instant acceptance from our extroverted family members, professors, classmates, colleagues, bosses, judges, clients, and opposing counsel. Far from it! In marked contrast, this process requires a dogged willingness to examine ourselves from all angles: personality traits, physical habits, preferences when engaging socially, and historical internal messages that might have served a purpose in the past but are no longer helpful or constructive today. We must carve out a space to discover—perhaps for the first time in our lives—the toxic talking heads occupying our internal news feed, officially banish them all, and replace them with one solid, forward-thinking, personal mission statement.

Flowers describes how “human beings have two principle modes of operation: being mode and doing mode.”270 He reveals: “Being mode offers resources for learning, healing, and well-being that doing mode can’t access. In being mode there is no judgment or striving, whereas in doing mode it’s hard to stop judging and striving.”271 Instead of trying to “do something” about introversion, shyness, or social anxiety in the legal panorama, individuals first need to just be quiet, shy, or anxious. Shifting to “being mode” affords us the luxury of observation, so we can actually see and recognize detrimental triggers and responses—like peeling back a hazy film from a glass window to reveal a clear vista.272 Flowers offers a great quote from Tao philosopher Lao Tzu: “To be, don’t do.”273 Likewise, Drs. Markway and Markway advise individuals to “stop working so hard to prevent your anxious reactions.”274 Let the reflexive stress responses happen so they can be “illuminated,”275 and then repurposed.

It takes a strong person to look behind the curtain, but we have good role models. Socrates is reported to have “worked every day of his life to ‘strengthen his soul’ in four ways: Self-control, Authenticity, Self-discovery, Self-development.”276 As did Swiss psychiatrist and psychotherapist Carl Jung, who “devoted himself to the soul-work of ‘going within’ to seek authenticity, self-knowledge, and self-creation.”277 It’s time for us quiet folk to shed the mask, the costume, the mantle of trying to be someone else, and be real.

THE SEVEN-STEP PLAN

So, how can we just be quiet law students or lawyers, capitalize on the positive traits of creativity, sensitivity, and empathy found in many introverted, shy, and socially anxious individuals, and contribute influential advocacy in the most authentic way possible?

Drawing from the advice of many psychology experts whose work is codified in the bibliography of this text, the next half of this book offers introverted, shy, and socially anxious law students and lawyers a seven-step self-study progression. Over the arc of the seven steps, we will examine ourselves as human beings, students, and attorneys, to identify and understand individual personality preferences, stress triggers, and mental and physical manifestations of anxiety in the legal world. Then, we will develop a gradual realistic program to convert perceived weaknesses into strengths, participate authentically in the law school and law practice experience, and become powerhouse advocates. Flowers, in his book, The Mindful Path Through Shyness, encourages an attitude toward self-examination that really is the opposite of “just do it”; “[i]t’s certainly not a matter of toughing it out or shutting down your emotions and forcing yourself to endure things you hate.”278 Instead, he suggests, “[i]f you can create a little distance between yourself and your thoughts and learn to examine these creative narratives as mental events rather than facts of reality, you can begin to dismantle some of the personal narratives that create so much anxiety.”279 He distinguishes between a rational, analytical, harsh, judgmental “taskmaster” method of change and a non-judgmental, “non-striving,” “mindful” approach, focused on enhancing personal “awareness, intuition, acceptance, and compassion.”280

The following program tailored for quiet law students and lawyers synthesizes the guidance of the many experts referenced herein, and merges their advice into a seven-step sequence built specifically for the legal framework. While specialists use varied terminology to describe the developmental increments along this expedition, consistent themes resonate. For example, Dr. Breggin recommends three tasks to achieve freedom from unproductive emotions: (1) “learn to identify the weeds,” (2) “reject and pull [them] out,” (3) “replenish” and “select and cultivate” fresh emotions.281 In the same vein, the process that actor and public speaking consultant Ivy Naistadt offers for understanding and conquering “stage fright” has four prongs: “(1) discover and acknowledge, (2) release, (3) reframe, and (4) visualize and make real.”282

Here’s our seven-part plan:

- Step 1—Mental Reflection: Begin listening carefully to, and then transcribe verbatim, the negative messages that automatically launch and replay in your head in anticipation of, or during, a law-related interpersonal interaction. Get the messages on paper. All of them. Word-for-word. Then, try to identify their original sources. Start to realize and acknowledge that the sources and messages are no longer relevant in the legal context today.

- Step 2—Physical Reflection: Start noticing each physical reaction triggered by the anticipation of, or participation in, an interactive law-related event. Describe the physical manifestations as specifically as possible—on paper. Blushing? Sweating? Shortness of breath? Trembling? Stomach-ache? Migraine? How and when does each physical response begin, crescendo, and eventually subside? Note your default physical protective stance: Hunched shoulders? Crossed legs or arms? Averted gaze? Are you making yourself small or closing inward, trying to go unnoticed or unseen?

- Step 3—Mental Action: Begin ejecting unhelpful messages from the past and crafting useful taglines and prompts for the future. Delete the old censorious messages and write motivating new ones.

- Step 4—Physical Action: Adopt new physical stances, postures, and movement techniques to better manage and channel excess energy ignited by a law-related interpersonal exchange. An open, well-aligned, physical comportment will help increase blood and oxygen flow, enhance thought clarity, and power voice strength.

- Step 5—Action Agenda: Construct a reasonable and practical “exposure” agenda, brainstorming a series of realistic law-based interpersonal interactions and ranking them from least stressful to most anxiety-producing. Through this thoughtfully structured chronology, and with careful planning and mindful intent, we will experiment with modified mental and physical approaches to each agenda event, with the goal of capitalizing on quiet strengths and amplifying our authentic voices.

- Step 6—Pre-Game and Game-Day Action: Develop personalized mental and physical pre-game and game-day routines for each law-related exposure agenda item. Then, step into each exposure event, consciously integrating the new mental messages and physical adjustments adopted in earlier steps.

- Step 7—Post-Action Reflection, and Paying It Forward: Reflect on and acknowledge successes and challenges within each exposure event. Tweak the pre-game and game-day routines for each subsequent exposure agenda item. Continue visualizing your ideal authentic lawyer persona. What does that quiet lawyer look like? How does he/she act, speak, think, write, analyze, communicate, participate, help, listen, or create? Note your impactful moments as a quiet yet magnanimous, altruistic, and empathetic advocate. Share your story and empower others.

By working this process, perhaps even more than once, inevitably you will start to feel calmer throughout the arc of each interactive event. You will note the inevitable rise of mental and physical anxiety symptoms—recognizing that initial reticence might always appear instinctively—and the increasingly faster dissipation of those pesky stress feelings and biological reactions. As you grow into your authentic lawyer voice, your impact in the law will solidify and strengthen. Together we will create a happier, healthier profession.

AUTHENTICITY

The goal throughout this seven-step excursion is authenticity. No more “fake it till you make it.” Just the opposite. Just be it. Be yourself, enhance self-awareness, make hyper-conscious mental and physical strength adjustments, and you will make it. Not as rhyme-y a catchphrase, but light years more effective. As Naistadt points out: “To be a good communicator, you have to be authentic, which requires finding out what’s stopping you from being authentic, an approach [to which] many programs on public speaking give little regard.”283

NO QUICK “FIX”

This process takes time. Drs. Markway and Markway emphasize its gradual nature: “Don’t do too much too soon.”284 There is no overnight, instant, “quick fix” to amplifying our voices or eliminating anxiety in the legal world, and in fact, we do not need to be “fixed.” Take your time. Don’t just do it. If we scramble to don our sneakers and bungee-jump off the cliff to presumed psychic freedom, we will never notice the crocuses blooming on the precipice, the texture of the sweatpants of the guy strapping on our harnesses, the foamy whitecaps of the river rapids below. We need time to reflect on our histories; let vignettes from childhood, adolescence, and adulthood coalesce in our minds; and recall past human interfaces that might have contributed to the current silencing of our voices—like a hidden optical illusion that suddenly becomes obvious. Our steps forward might be plodding at first, not fleet-footed, but the journey eventually will transform not only us, but our law school communities and legal system.

CHANNELING YOUR INNER PRIVATE INVESTIGATOR

On this expedition, we are going to observe every facet of ourselves. Like detectives on a stakeout, we will study incremental mental and physical nuances. “Hmmm, that professor’s questioning of my classmate across the room made me clench my left fist … Wow, the mere thought of delivering that oral argument made me pull my baseball hat brim lower over my eyes … Interesting, when the partner asked me to defend that deposition, I lost my appetite for the pulled pork barbecue sandwich sitting on my desk.”

We must be willing to observe our quiet selves, what makes us tick, what makes us happy, comfortable, angry, uncomfortable, stressed, panicked, freaked out, and relaxed. We must gaze (gently) back as far as we can remember and identify moments when we experienced shame, embarrassment, guilt, or censorship, or felt ignored, invisible, judged, or criticized for being quiet or just for being ourselves. We might need to rappel to sometimes daunting depths, excavate through the mental vines, bushwhack our way through the debris, and churn the desiccated soil.

This is exciting stuff.

DIFFERENT JOURNEYS FOR DISTINCT INDIVIDUALS

As noted in Chapter 1, quietude has many shades. The non-shy introvert’s experience along this seven-step path likely will vary from the shy or socially anxious individual’s evolution.

For introverts who do not necessarily suffer from shyness or social anxiety but still encounter discomfort and strain in situations mandating spontaneous expression about the law, an enhanced awareness of introvert assets is the initial goal. Dr. Laney validates that “[i]f [introverts] are not helped to understand how their mind works, they can underestimate their own powerful potential.”285 Tanner agrees, “I believe that introverts are a blessing to the world … but unless we learn to express this we will not be able to offer the gifts that we bring.”286 In this journey, I recommend that introverts first reflect on their preferences in law school or law practice for studying or researching quietly, having time to reflect before conversing about the law, writing prior to speaking, and working independently (at least at first) rather than in teams or groups. We can acknowledge the effectiveness of these habits in helping us generate quality work product, while at the same time comprehending perhaps for the first time how—and why—certain aspects and characteristics of law school or practice can be challenging for introverts. Then, the introvert’s seven-step process will entail identifying any sources of messages suggesting that quietude is out of place in the law, deleting those scripts, and reframing our thinking. With this foundation, introverts can build upon innate strengths, develop tailored plans for mentally and physically tackling initially daunting law-related scenarios, and use introvert traits and preferences in the most effective yet authentic way—ultimately fulfilling, and exceeding, the expectations of law professors, law office bosses, clients, and judges.

Shy and socially anxious individuals who experience a deeper level of angst while roving through the law school experience or piloting their daily lives as lawyers can use the seven-step process slightly differently: going deeper to explore historical catalysts of self-censorship, and expunging psychological and physical barriers to speaking their minds in the legal area. For these folks, Naistadt reiterates the need for more than surface-level Band-Aid quips and tips:

Look at it like putting out a fire where there is a lot of billowing smoke. Similar to nervousness, which is just a symptom of what’s holding you back, the smoke is just a symptom of the fire. Aiming the hose at the smoke won’t put the fire out. You need to identify the source of the fire in order to extinguish it. Without adding this critical component to the mix, no amount of tools, tips, or other how-tos for auditioning, interviewing, speechmaking, or presenting effectively will produce results that last.287

To tackle interpersonal anxiety, we have to be willing to go deep. Naistadt urges: “The key to speaking without fear is exposing the core issues behind your stage fright (issues that can be different for each of us but have common denominators) and rooting them out, then developing a solid technique you can count on for creating and delivering your message.”288 Whittling down to the true core of what is holding us back from finding our lawyer voices is “the overlooked weapon in the communicator’s arsenal, and very often the most important one.”289

Finally, some of you might never have considered yourself to be an introverted, shy, or socially anxious person and are wondering why you suddenly have a blushing problem or recurring migraines at the thought of attending a certain law school class or taking a deposition. Before law school or law practice, you might have been outgoing and gregarious, thrived in social exchanges, acted in plays, reveled on the athletic field, served on the debate team, held a leadership position, or taught classes. But law school or practice has pressed a big red “MUTE” button and you have lost your voice. You might have situational public speaking anxiety activated by the interruptive dynamic of the professor-student or judge-attorney Socratic exchange, or the perceived antagonistic nature of oral arguments or negotiations. Not to worry. Your seven-step process will help you identify past internal messages that currently are impeding your lawyer voice, understand their potential origins, realize their present-day irrelevance, adopt new taglines reflecting your current and future authentic lawyer persona, and mindfully construct a realistic strategy for tackling each public speaking scenario in your own style.

WE CONTROL THE DELETE-AND-RE-RECORD BUTTON

It can be quite revelatory when we discover that troubling cognitive, physical, and behavioral responses accompanying a distressing law-related event are simply knee-jerk automatic reactions from years of reinforcement of outdated messages. Routinely, we meander through life completely unaware of these programmed emotional loops. Usually, unless or until something traumatic happens, we do not investigate and study them, though, as Flowers points out, “they can be extremely predictable and create a great deal of suffering.”290 When we finally halt, listen, and transcribe the negative messages replaying in our heads, recognize disturbing physical manifestations of stress, and note unhealthy reactionary behaviors (avoidance, self-shaming, self-criticism), we can interrupt the noxious spin cycle and launch a whole new sequence. Flowers emphasizes that past patterns might be well ensconced and need tough extraction but they are not permanently fused; “the most troublesome components of shyness are things you can work with: thoughts, emotions, sensations, and behaviors that are impermanent, malleable, and within your personal capacity to change.”291 He reassures that we “can take the whole thing off of automatic pilot.”292

We proceed from here mindfully and deliberately, as introverts naturally do. Ours is not an issue that can be solved in one, immediate swoop by ripping off a psychological Band-Aid, by ziplining away from a painful past, or by diving into the deep end of emotional confrontation. It is a process that starts slowly and purposefully, and consciously increases momentum with small successes, each incremental step a necessary component part of our overall greater triumph.

So, are you ready for transformation?

Exercise #1

Christopher Phillips, who conducts Q&A gatherings called Socrates Cafés around the world, quoted one of his participants, Wilson from Ecuador, as querying: “[W]hat I really want to know is, is it possible to be silent if everyone else around you is screaming?”293 I promise, it’s possible. Let others scream. But to thrive in our quietude, we first must become hyper aware of our context (our surroundings, cast of characters, and events) in the legal world so we can pinpoint the specific aspects of our environments that trigger unnecessary stress and anxiety. Then, we can disconnect any negative ignition switches and take command of our new impactful role in the field of law.

To get started on your “just be it” journey, go to your favorite stationery store or bookstore and buy a new journal. Or, if you bond better with your electronic device, access your preferred note-taking feature or app. Find a quiet place and contemplate the following questions:

- While in law school or law practice, have you felt overwhelmed around other people in certain situations? If so, what was happening around you? How many people were in the room or occupying the space? Who were they? What sounds do you remember? What other external stimuli do you recall? Lights? Smells? What exactly were you doing, or being asked to do, in that moment? What was your role? What were the roles of the other individuals present?

- Have you experienced anxiety anticipating or participating in an interaction with one particular person in the legal world? If so, who was that person? Was this person an acquaintance, a stranger, an authority figure, a peer? Were you afraid of something? Try to be specific. “I was afraid he/she would …” “I was afraid I would …”

- Have you experienced anxiety anticipating or participating in an interaction with a few other people in a law-related scenario (i.e., a small group)? If so, were these people acquaintances, strangers, authority figures, peers? Were you afraid of something? Try to be specific. “I was afraid they would …” “I was afraid I would …”

- Have you experienced anxiety anticipating or participating in an interaction with a large group of other people in the legal environment? If so, were these people acquaintances, strangers, authority figures, peers? Were you afraid of something? Try to be specific. “I was afraid they would …” “I was afraid I would …”

- Do you experience anxiety toward public speaking in the legal context? If so, is this a new feeling for you or a lifelong struggle? Describe the first instance you felt anxious about a public speaking event in the legal arena. What were you asked to do? (Participate in a Socratic Q&A? Present a case? Give a speech? Deliver an argument? Negotiate?) Who asked you to do it? Who else was present?

- If you experienced public speaking anxiety before law school or practice, describe a few of the most memorable episodes. Be specific. What was the event? What was the topic? Who was present? What exactly did you fear? Did you experience physical stress symptoms? What precisely did you feel?

- Do you recall a performance-oriented event from your past (before law school or practice) in which you felt little or no apprehension or anxiety? What was the scenario? Who was present? What was your role? What went well? What did you enjoy about the experience? How did the circumstances or logistics of this event differ from law-related performance events that trigger anxiety?

- Does delivering a prepared speech (without interruption) give you less anxiety than speaking in front of an audience and being interrupted with questions, or are both scenarios equally anxiety-producing?

- Is there at least one performance-oriented scenario in the non-law-related part of your life that you enjoy? Is it leading an exercise class, running in a 5k, playing music for others, guiding a tour, teaching a workshop?

- In what scenario(s) do you feel most confident in your life? Are you taking a test? Participating in a sport? Playing an instrument? Teaching kids? Writing? Traveling? Cooking? Painting? Dating? Hosting a party?

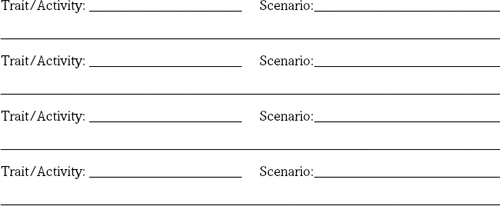

Now, let’s take a moment to think about our quiet personas. Which of the following traits or activities do you identify with or enjoy?

- Listening: Do you consider yourself a good listener? How do you listen when others are talking? How do you physically position yourself? Where do you focus your attention? Do you maintain eye contact? How do you demonstrate to the speaker that you are listening?

- Data-gathering: Are you a good note-taker? How do you capture the thoughts of others, and your own thoughts, while others are speaking?

- Perceiving: Do you consider yourself a perceptive person? Do you notice details that other friends miss? Sights? Street signs? Landmarks? Facial expressions? Smells? Tastes? Patterns? Textures? Sounds? Other people’s emotions?

- Researching: Do you consider yourself a good researcher? How do you go about researching something or trying to figure out the answer to an unknown? What do you do when you get stumped? If you can’t easily find an answer, are you comfortable changing tactics and trying new research angles or sources?

- Creative thinking: Do you consider yourself a creative person? This does not necessarily mean artistic, but instead, being innovative in your thinking. Do you come up with interesting or even wild ideas for solving problems?

- Deep thinking: Do you consider yourself a deep thinker? Do you find yourself wrestling with problems or concepts to figure them out?

- Writing: Do you enjoy writing? If so, what type of writing? It doesn’t have to be legal writing. Think about what genres of writing you enjoy: Text messaging? Creative Facebook posting? Emails? Poems? Songs? Letters?

- Choosy speech: Are you a person of few words or do words come easily to you? Do you like finding the right word to express a thought? Do you think about how to phrase your ideas before relaying them aloud? When you speak, are people sometimes surprised at the depth of your ideas?

- Negotiating: When you negotiate, do you prefer a win-win effort, or a winner-takes-all competition?

- Tolerating silence: Are you comfortable with silence? Why or why not? If so, with whom?

- Modeling empathy: Do you consider yourself an empathetic person? Are you able to listen to another person describe his or her experiences and understand that person’s reactions, feelings, perceptions, and choices—even if they are different from your own? Do you convey to others that you understand their feelings or emotions? If so, how?

Now, try to recall specific situations in which any of the foregoing inherent traits or activities were beneficial in solving a problem, resolving a conflict, achieving progress in a stalled situation, or counseling another person through a difficult circumstance.

Going forward, we are going to focus on capitalizing on our natural strengths as quiet individuals to amplify our authentic lawyer voices.