Elizabeth P. Lawlor

Illustrations by Pat Archer

Most people identify trees by their leaves. This makes tree identification a special challenge in winter. This may not be a disadvantage, because it forces you to observe the more subtle differences among trees.

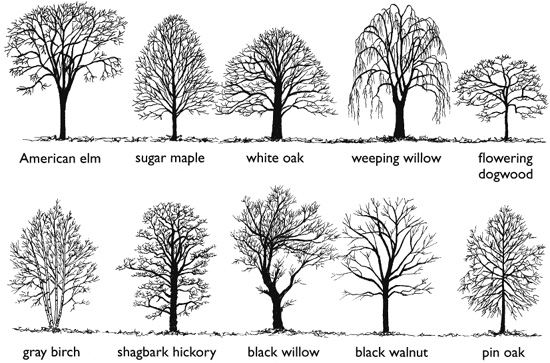

Deciduous trees are those that shed their leaves in the fall. Without their leaves, you can see the trees’ various shapes. This is an ideal time to learn about branching patterns. The diagrams will help you determine which pattern each tree illustrates.

1. Whorled branches grow out of the trunk in threes. This occurs rarely, but you can find it easily in larches (pine family), a deciduous gymnosperm.

whorled (third branch on the other side)

2. The branches, twigs, and leaves are paired in some trees. Look for this pattern, called opposite, in maple, buckeye, ash, dogwood, and horse chestnut.

opposite, or paired

3. The third pattern of branch arrangement is called alternate. The branches and twigs grow in spiral steps.

alternate

Branching as seen in winter

If you would like to learn more about patterns in nature, read Fascinating Fibonaccis, by Trudi Garland.

Within the parameters of a tree’s genetic code, its shape is determined by its environment. A tree growing in an open space will develop a different shape than will a tree of the same type growing in more cramped quarters such as woods or an urban park. A tree that grows close to its neighbors will have normal-sized limbs only near its top, with perhaps a few underdeveloped limbs along the length of its trunk. Look for this kind of stunted development.

The shape of a tree aids in its identification. For example, a sugar maple is shaped like an egg standing on its broad end. An elm looks like an open umbrella or an upside-down bud vase. To see the distinct shape of a tree, you will need to observe the tree from a distance. You can easily do this in an open field or on a golf course.

Find a tree that interests you. Describe its shape in your notebook. Draw an outline of the tree or photograph it. Do the branches droop like those of a weeping willow? Do they spread out from the trunk like a white oak, or do they grow close to the trunk like a hickory? Are the branches growing in any particular direction? Besides the prevailing winds, what might cause the tree to grow in a particular direction?

It is difficult to determine the identity of many trees by examining only the bark. One reason for this is that as a tree ages, its bark changes. Nevertheless, there are some trees that have very distinctive bark and are easily recognizable throughout their lives.

The sycamore (Platanus occidentalis) is easily identified by its mottled and flaking bark. It is frequently planted as a shade tree, and you can find it in parks and along urban and suburban streets.

A clue to the nature of the bark of shagbark hickory (Carya ovata) lies in the tree’s name. Strips of bark scroll away from the trunk and give the tree a shaggy appearance.

The bark of the American beech (Fagus gran-difolia) is smooth and gray or blue-gray.

The bark of the American hornbeam (Carpinus caroliniana) is often described as resembling flexed arm muscles.

WINTER TREE SILHOUETTES

American beech bark (Fagus grandifolia)

Shagbark hickory bark (Carya ovata)

American hornbeam bark (Carpinus caroliniana)

Sycamore bark (Platanus occidentalis)

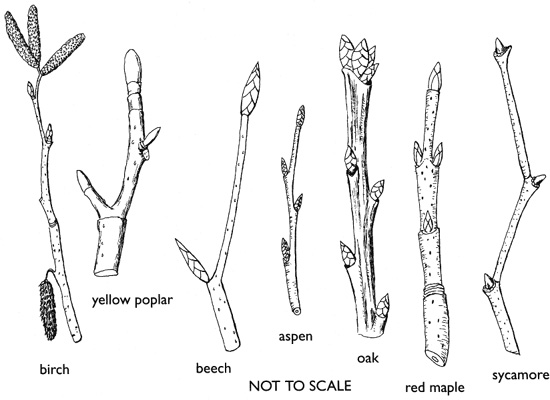

Twigs and buds are especially useful in identifying trees in winter.

Green ash twig with terminal bud.

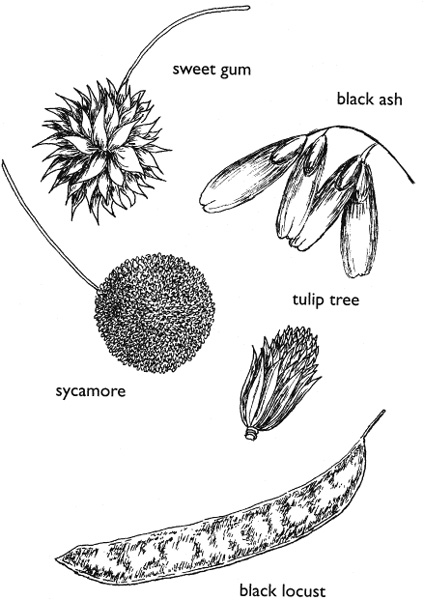

Many deciduous trees retain some seed containers throughout the winter.

Twigs come in a variety of colors, shapes, and sizes. Make a collection starting with beech, oak, shagbark hickory, and maple, if you can find them. How many colors are there among your twigs? Are they straight, zigzag, or curved? Study the additional twig traits described below. The illustrations will help you match twig with tree.

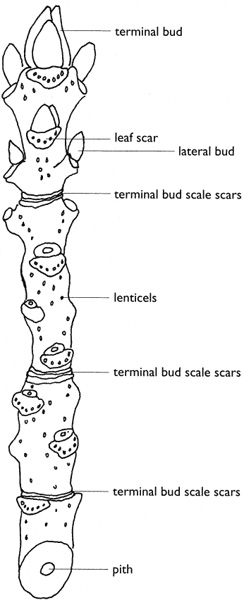

First look at the buds. The bud at the tip of the twig is called the terminal bud. As it develops, it adds length to the twig. The buds that grow along the side of the twig are called lateral buds. They produce flowers, leaves, or new branches. Each bud is covered by overlapping scales that protect the developing tissue.

The characteristics of the terminal bud can help you identify the tree. Is the bud single or in a cluster? Is it large or small? Pointed or rounded? Hairy? Sticky? What color is it? Oak twigs have clusters of three or four terminal buds protected by brown or reddish brown scales. Beech tree twigs have only one terminal bud. Like the lateral buds, it is shiny tan and cigar shaped. Red maple twigs have a single round, dark red terminal bud. The terminal bud of shagbark hickory is elongated with blunt tips, hairy, and usually dark brown.

Now look at the lateral buds along the sides of the twigs. How do they resemble the terminal buds?

The small dots you see on new or young twigs are lenticels. These are openings in the outer layers of the stem and root tissues that allow the exchange of oxygen into and carbon dioxide out of the plant. Is there a pattern to the arrangement of lenticels? How far back on the twig can you find them?

Twigs will also show leaf scars. During the summer, the tree produces a layer of cork between the leaf stem and the point where it attaches to the twig. When this layer is complete, the leaf falls, and the mark left on the twig is called the leaf scar. The shape of the leaf scar is unique for each type of tree. If you look closely at a bare twig, you will see tiny dots in the leaf scar. These dots mark where the transport tubes of the twig joined those of the leaf and are called the vascular bundle scar. The illustrations on page 100 show lateral buds and leaf scars on selected twigs. You will notice that they come in a variety of shapes and sizes. The color of the buds also will vary according to the type of tree.

The terminal bud scar is the point where the bud scales of the terminal bud were attached. The space between rings, which look like rubber bands around the twig, mark each year’s growth. In what year did your twig grow the most? Look at other twigs the same age on the same tree. Do they also show the most growth during that same year?

If you cut into a twig, you will find a sponge-like substance called pith. When placed in a growth medium, pieces of pith grow into new plants. Cut a cross section of twig and examine the pith. If it is star-shaped, it is probably an oak, poplar, or hickory twig. If the pith is circular, it is probably an elm twig.

Many deciduous trees retain some seed containers throughout the winter. You can easily see the button balls, or seed clusters, of the sycamore dangling from the zigzag twigs. If you live in an area where sweet gum (Liquidambar styraciflua) thrive, look for the spiked seed balls. Clusters of winged seeds that hang from branches announce the ash. The yellow poplar or tulip tree (Liriodendron tulipifera) produces seed clusters that resemble a tulip blossom. Ash trees (Fraxinus spp.) retain bunches of winged seeds. See if you can find these and other trees that retain some seed containers throughout the winter.

—From Discover Nature in Winter

Elizabeth P. Lawlor

Illustrations by Pat Archer

When you first walk into the forest on a hot summer day, you are relieved to feel the cool, moist shade. As you walk along the path, you notice the small trees and bushes that thrive in the sun-mottled shade, as well as dense patches of ferns. Ferns are especially abundant in the wet areas near streams.

These common woodland plants have an exotic, ancient aura to them, like prehistoric relics. Ferns and their close relatives actually did flourish in the steamy forests of the dinosaur ages in the Carboniferous period, about 350 million years ago. The stable climate of that time encouraged their growth. Flat, marshy land and vast inland seas contributed to the success of these early land-dwelling plants. The forests of ferns they created flourished over a large portion of the earth, including what are now the icy polar regions. The cooling climate that followed this period resulted in the evolution of the ferns we see today, which are adapted to changing sets of environmental conditions. Today there are some twelve thousand fern species, about four hundred of which live in the United States, and about one hundred of those in the Northeast. Ferns of various sizes and shapes live in a diversity of habitats, ranging from tropical rain forests to the arctic tundra. Robust, eighty-foot-tall fern trees thrive in the tropics, and dainty, two-inch leaves of curly grass fern (Schizaea pusilla) grow in the acid soils of southern New Jersey bogs. You also can find ferns in such unlikely places as the marshlands of northern Alaska and even Antarctica. However, few grow in arid deserts.

Ferns were the first plants with vascular systems. These systems carry minerals and water to the food factories in the leaves and the manufactured nutrients from the leaves to all parts of the plant. They also provide support so that these plants can stand upright.

Ancient mythology often attributed magical qualities to ferns. People noticed that ferns did not possess obvious structures related to reproduction, such as flowers, fruits, and seeds, but the plants continued to appear year after year. Compared with other plants, the ferns were a strange anomaly.

A rudimentary understanding of how ferns reproduce dates back only three hundred years, to 1669, when spores were discovered. But at that time, scientists were unable to make the connection between these tiny structures and fern reproduction. It was not until the mid-eighteenth century that this relationship became clear. However, the scientific explanation itself is quite an intricate tale filled with strange terminology.

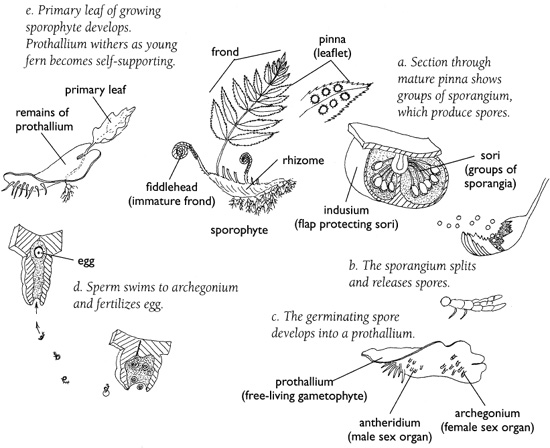

Spores are tiny cells that do not contain a baby plant or embryo. Therefore, spores do not become new ferns, but if they fall on suitable soil and have adequate water, they will divide and produce a tiny structure called a prothallium (plural, prothallia). These flat, often heart-shaped structures lack leaves, stems, roots, and vascular systems. Prothallia get their nutrients directly from the surrounding water, which doesn’t have to be more than a thin film over the ground. The prothallia are small, growing only to about one-fourth inch in diameter, and are only about one cell thick except near the center. In this slightly thicker region, on the underside, two small structures develop. One of these is the archegonium, which contains an egg, and the other is the antheridium, which contains antherozoids or sperm. Spores need moisture for fertilization to take place, as the antherozoids must swim to the archegonium. The fertilized egg that develops from this union eventually becomes the plant we recognize as the fern. During this development, the prothallium withers, and the young fern becomes self-supporting. Often referred to as the private life of the fern, this phase in the two-part life cycle of a fern is called the gametophyte generation.

The self-supporting fernlets have tightly coiled, bright green heads, called crosiers, or fiddleheads, which poke their way through the soil in the spring. As the fern matures, the coils straighten into leaves, or fronds. With the unfurling of its young fronds, the fern enters another stage of its life cycle. Now its job is to produce spores. Some ferns produce hundreds of thousands of spores, and other, more prodigious ferns produce millions.

LIFE CYCLE OF FERNS

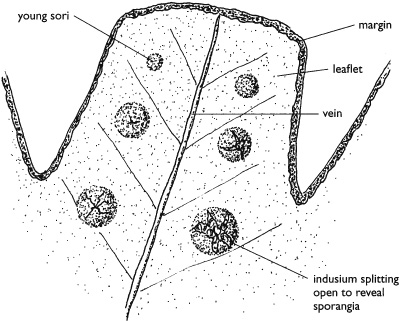

Individual fern species have their own unique patterns of spore production, but generalizations about this process can be made. In the spring, tiny green bumps appear on the undersides of the leaves. As the season progresses toward summer, these bumps turn brown, and the leaves may look as though they are growing fungi. These dark brown spots are called sori, and they contain spore cases, or sporangia. Sometimes the sporangia are covered with a thin protective membrane called an indusium.

When the sportes are mature, they are released from the sporangium. The method of release varies among species. In some ferns, the spores are shot into the air by a slingshot-like mechanism. In other species, the spore cases simply open, and the spores are caught in air currents and drift away from the parent fern. Whatever the discharge mechanism, the spores of all ferns become airborne with the slightest breeze, even by an imperceptible movement of air.

Relatively few spores come to rest on suitable soil. Those that land in warm, shady, moist places at the right time of year will begin to grow. If conditions are not appropriate at the time of their landing, the spores remain alive but inactive for as long as a year. This spore-producing phase in the life cycle of a fern is called the sporophyte generation.

The complete life cycle of a fern is even much more complicated than has been outlined here. If you keep in mind the following, however, you can easily remember the essential steps in the cycle: 1. Fronds produce spores. 2. Spores develop into prothallia. 3. Prothallia manufacture gametes. 4. Gametes fuse to produce a new fern (the sporophyte). In the [Observations] section, you will have an opportunity to explore this process in some specific ferns.

This pattern of shifting between asexual and sexual development is known as alternation of generations. Although it is the usual pattern of fern reproduction, not all ferns are restricted to it; some can reproduce vegetatively as well. One way they do this is by the branching and rebranching of their rhizomes (a special type of stem). Some ferns send out a “feeler” rhizome that roots some distance from the parent fern. When this happens, a new population of ferns appears where there were none before.

Ferns also can reproduce asexually by vegetative reproduction of fronds, roots, or rhizomes. This method does not use spores or require the union of gametes, and the offspring are identical copies, or clones, of the parent plant. As long as the habitat conditions meet the requirements of the parent plants, the clones and resulting population will survive.

The rare walking fern (Camptosorus rhizophyllus) demonstrates a form of vegetative reproduction. Its long, lance-shaped fronds arch away from the center of the plant. When the tips of the fronds touch the earth, they produce roots and new plants. Because the new plant was not produced through the union of gametes or sex cells, it is a clone of its parent.

The Boston fern (Nephrolepis exaltata bostoniensis), used frequently as an interior decoration, reproduces vegetatively through the use of runners, stringlike leafless stems that develop among the fronds. These runners will sprout roots wherever they touch soil.

Buds on the roots of the staghorn fern (Platycerium sp.) develop into fernlets. Some less familiar ferns develop clones on the upper surfaces of their fronds. Eventually the new ferns will leave the parent fern, develop roots and rhizomes, and become independent ferns.

Most ferns are perennials. When it turns cold at the end of the growing season, the fronds of these ferns turn brown and become brittle. Their life above the ground is over, but the rhizomes continue to live throughout the winter. When spring arrives, new shoots will sprout from the rhizomes. If you feel around a clump of ferns in the autumn, you may feel some hard, round forms. These are the beginnings of the fiddleheads that will appear next spring.

Some ferns are evergreen and, along with pines, cedars, and hollies, provide a splash of color to the winter landscape. The common Christmas fern (Polystichum acrostichoides), which gets its name from the eared, stocking-shaped lobes of its fronds, is an evergreen fern you might find along wooded sloping streambanks, near stone walls, and in rocky, wooded areas. The marginal wood fern (Dryopteris marginalis) and the rare hairy lipfern (Cheilanthes lanosa) are frequent members of the rocky slope community.

Wherever they grow, ferns lend a subtle feeling of wildness to their habitat. Compared with the cheery spring blooms of wildflowers, ferns are subdued and are easily ignored. However, there is great diversity and beauty to be found. Find some ferns. Make a commitment to spend a season with them, observe them, ask questions, and learn what they have to tell you. They might just develop into a lifelong passion. The activities that follow will help give you a new and rich perspective on these fascinating plants.

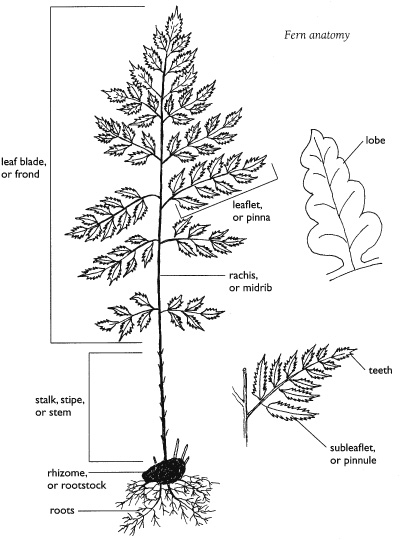

In the activities below, you will discover a world of plants very different from the flowering plants of fields and gardens. On ferns, you will not find the familiar flowers, fruits, and seeds. Instead, fronds, sporangia, and prothallia will be your new companions as you navigate through this complex yet beautiful world. The ferns you will examine in these activities are not restricted to wetland habitats, but are common and easily found. Use the diagram below to help familiarize yourself with some fern anatomy and the vocabulary that goes with it.

Frond, or Leaf Blade. The flat, green leaf blades, or fronds, the most conspicuous part of the fern, vary in size and shape. Fronds are usually compound, with leaflets, or pinnae, attached along a rachis, or midrib. The fronds manufacture food through photosynthesis. Some species have sterile and fertile leaves of different sizes and shapes. Fertile fronds contain reproductive spores. Fronds vary in size and shape in different species.

FERN ANATOMY

Stipe, or Stalk. The stipe, or stalk, is the leaf support below the rachis and above the root. It is covered with hairs or scales, rounded in back and concave or flat in front, and green, brown, tan, silver, or black in color.

Rachis. The rachis is the backbone of the frond and is the continuation of the stalk supporting the leaflets. It corresponds to the midrib of a simple leaf. Until the lobes in a fern are cut to the midrib, there is no rachis.

Leaflet, or Pinna (Plural, Pinnae). Leaflets are divisions of a compound leaf.

Subleaflet, or Pinnule. Subleaflets are subdivisions of leaflets.

Lobe, or Pinnulet. Lobes are the subdivision of a pinnule.

Teeth. Teeth are serrations along the edges of the pinnae, pinnules, or pinnulets.

Rhizome. Rhizomes are horizontal stems that lie on the surface of the soil or just below it.

Roots. Roots are thin, threadlike, sometimes wiry structures that anchor the plant and absorb water and minerals from the soil. They grow from the rootstock, or rhizomes.

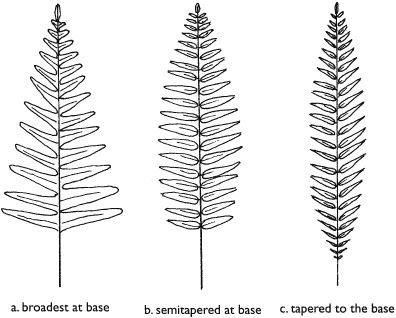

The shape of a frond will help you identify an unfamiliar fern. Is the frond triangular and broadest at the base, does it become narrow at both ends, or is it tapered only at the base?

Frond shapes

Fronds come in many shapes and may be undivided, somewhat divided, or much divided into smaller parts.

Ferns vary in appearance. Some are extremely delicate; others are more substantial. There are differences in the lobes, leaflets, and subleaflets. Ferns are organized into groups having similar leaf patterns, which makes fern identification somewhat easier. Botanists who specialize in ferns use an even more detailed system than the one presented here to help them categorize these beauties.

Undivided Ferns. These ferns are very unlike the typical fern. The simple leaves are straplike and lack the feathery appearance of most ferns. These include the rare walking fern and the bird’s nest fern (Asplenium nidus), often grown as a houseplant.

Simple Ferns, or Lobed Ferns. Fronds of these ferns are divided by cuts on either side of the midrib but do not touch the midrib. The common polypody (Polypodium virginianum) has this design.

Compound Ferns. These ferns are cut into distinct leaflets to the midrib.

Once-cut ferns. Each leaflet, or pinna, is cut to the midrib. Ferns in this group are the sensitive fern (Onoclea sensibilis) and Christmas fern.

Twice-cut ferns. In these ferns, not only are the fronds cut into leaflets, but the leaflets are also cut into subleaflets, or pinnules. They include the marsh fern (Thelypteris palustris), cinnamon fern (Osmunda cinnemomea), ostrich fern (Matteuccia struthiopteris), and marginal wood fern.

Thrice-cut ferns. In these, the laciest of ferns, the fronds are cut into leaflets (pinnae), which are cut into subleaflets (pinnules), which are cut again into pinnuletes. The common bracken fern (Pteridium aquilinum) of open fields and woods and the lady fern (Athyrium filix-femina) of moist, shaded woods are thrice-cut ferns.

Walking fern (Camptosorus rhizophyllus).

Hartford climbing fern (Lygodium palmatum).

Curly grass fern (Schizaea pusilla).

Unfernlike Ferns. There are a few rare ferns that, in spite of their unfernlike appearance, are classified as ferns because they are vascular plants that reproduce by spores rather than seeds. The walking fern (Camptosorus rhizo-phyllus) prefers the northern face of moist limestone outcrops. The Hartford climbing fern (Lygodium palmatum) has vinelike fronds that climb and twist over shrubs and other obstacles in the partial or deep shade of low thickets and along streambanks in moist, wet, acid soil. It prefers sun, but the rhizomes must be wet. Curly grass fern (Schizaea pusilla) grows in wet, very acid soil, such as that found in cranberry bogs and cedar swamps. It is found in New Jersey, Nova Scotia, and Newfoundland.

Ferns are easier to find than you might think. You will find them to moist, shaded areas, along riverbanks, around ponds, and in the woods. Here are brief descriptions of three common ferns you are likely to find growing in swampy areas and in wet woodlands.

The cinnamon fern has twice-cut fronds and a separate cinnamon-colored fertile frond growing from the rhizome that bears club-shaped sporangia. The tall, pointed sterile fronds grow in a circular pattern.

The ostrich fern has tall, plumelike, twice-cut sterile fronds that are wider in the middle and taper toward the base and the top of the frond. The fertile frond is also plume shaped, and its tough pinnae clasp dark brown clusters of sori.

The marsh fern also has twice-cut fronds. You can distinguish between sterile and fertile fronds by the presence of sori on the fertile fronds, which are also taller and thinner than the sterile fronds.

You need not limit yourself to ponds to discover the fascinating world of ferns. Other ferns grow in habitats such as roadside ditches, meadows, and damp, cool forests, and some even grow out of brick walls.

The sensitive fern is a very common fern with once-cut fronds, found in open fields and swamps. The wavy, lobed fronds do not produce sori, which means that they are sterile. A separate fertile frond appears during the fall. It contains small, brown, bead-shaped clusters containing sori that persist throughout the winter.

The common polypody grows in rock crevices in woodlands. The sori develop on the undersides of the upper lobes. The fronds are once-cut.

Cinnamon fern (Osmunda cinnamomea).

Ostrich fern (Matteuccia struthiopteris).

Marsh fern (Thelypteris palustris).

Sensitive fern (Onoclea sensibilis).

The Christmas fern has leathery, evergreen, once-cut fronds with a tough stipe and rachis. The fertile pinnae are limited to the top third of the frond, where there are reddish brown sori on the underside.

The marginal wood fern has large, leathery, evergreen, twice-cut fronds and scaly stipes. The sori are located on the margin of each pinnule. Look for this common fern on rocky woodland slopes.

The bracken fern is common in woodlands and fields. It has very large, leathery, thrice-cut, triangular fronds. Look for sori around the edges of the undersides of pinnules that are folded under.

The lady fern has pointed, thrice-cut fronds with floppy tips. Short, straight, or curved sori develop on the undersides of the fronds. This is a common fern of moist, semi-shaded woods and fields.

Although the fronds of most ferns look identical, some of them produce spores and are called fertile fronds; others do not and are known as sterile or vegetative fronds.

Some ferns produce fertile fronds that do not resemble the leafy sterile fronds. The sensitive fern produces fertile fronds that look like small, thin sticks, each with many branchlets. The spore cases look like brown beads decorating the tiny branches. These fertile fronds live long after the sterile fronds have withered and died. The fertile fronds of the cinnamon fern look like cinnamon-colored sticks standing erect in the middle of a clump of bright green sterile fronds.

As you observe your ferns throughout the growing season, look for signs of fertile fronds. When do the fronds first appear? Do they all appear at once? If not, how long is the delay between frond appearance? When do the sori first appear? Are all the look-alike fronds on your fern fertile or are some sterile? When do the fronds, sterile and fertile, die back? On average, what is the lifespan of a frond? How many fronds does one fern produce in a season? Record your findings in your field notebook.

In the spring, bright green young ferns begin to poke up through the soil. As each emerges, you will see a coil of green called a fiddlehead, or crosier. These names refers to the coil’s shape, the first for its resemblance to the head of a violin, and the second for a bishop’s ceremonial staff also called a crosier, which is a stylized shepherd’s staff with a crook at the top.

The fiddleheads are coiled because the upper and lower surfaces of the fronds grow at different rates. As the fern grows, the fiddlehead unrolls and expands, revealing tiny new fronds. Sometimes the fiddlehead has a cover of fuzzy, brown scales. Some ferns have a cover of silky hairs on the rachis when the young fiddlehead unrolls. Before the development of synthetic materials, these hairs from large tropical tree ferns were used for upholstery stuffing.

Locate a patch of ferns during the summer months, and return there the following spring to observe the fiddleheads poke through the soil, unfurl, and release their folded leaflets. Record your observations in your field notebook. On what date do you first notice the fiddlehead? Is it wearing a brown, tan, or white fuzzy protective hood? How long does it take to reach its full height? Look for different types of ferns. Do all the ferns you observe have fiddleheads? Which ferns have them and which do not?

In the fall, you can find fiddleheads by poking around the base of the fern. They are tightly coiled, hard, round structures that hug the rhizomes and may be covered by a thin sheet of soil.

Some people relish fiddleheads as tasty vegetables, reminiscent of asparagus. The fiddle-head of commerce is the ostrich fern, great quantities of which are collected in the spring and shipped to markets or canneries. If you would like to investigate this gourmet aspect of ferns, try the following. (Caution: Do not eat fiddleheads you pick in the wild. Use only those you buy from a grocer.)

Select fiddleheads that are newly arrived to the grocer’s shelves, choosing only those that are bright green and tightly coiled. Cut off the long tails. Between your palms, rub away the fuzzy or brown, papery covering, and wash the fiddle-heads well. Steam them until fork-tender, and rinse in cool water. Dry them thoroughly, then toss with a favorite salad dressing. Or if you prefer, stir-fry them in oil with ginger to taste for about two minutes. Add two cloves of garlic, salt, and one-quarter cup of chicken broth. Cover and simmer for about five minutes.

If eating fiddleheads does not appeal to you, you can still buy a few and unfurl them to examine how the leaves are packaged.

Summer is the best time to look for ripe spores. You can tell which spores are ripe by the color of the sori, which will be a shiny dark brown. If the sori are white or green, the spores contained within the sporangia are immature. Withered or torn sori indicate that the spores have been dispersed.

On some ferns, the sori are covered with a thin membrane called an indusium, which can be curved, round, or long and narrow. These characteristics of the indusium vary among species and are used to help identify them. The size, shape, color, and location of the sporangia are also important clues in fern identification. The cinnamon fern has clusters of sori on separate stalks. On the ostrich fern, the sori are enveloped by leaflets with curved margins. On the bracken fern, the sori form a continuous line at the frond’s edge. The wood fern has scattered rows of sori and a kidney-shaped indusium. The marsh fern has sori near the margins and a kidney-shaped indusium.

When did the spores on your fern mature? Are they on all the green leafy fronds or only on some of them? Where on the frond are they located? Are they confined to the margins of the frond, or are they along the midrib? Are they on a distinctly different fertile frond? Are the sori covered with an indusium? Describe the sporangia. Make a drawing or take a photograph of your fern, perhaps from several different angles. Keep a record of your findings in your field journal.

Remove a mature frond with shiny brown sori and place it between sheets of white paper. In a day or two, remove the top sheet carefully and pick up the frond. Spores should be present on the bottom sheet.

—From Discover Nature in Water and Wetlands

U.S. Army

In a survival situation you should always be on the lookout for familiar wild foods and live off the land whenever possible.

You must not count on being able to go for days without food as some sources would suggest. Even in the most static survival situation, maintaining health through a complete and nutritious diet is essential to maintaining strength and peace of mind.

Nature can provide you with food that will let you survive any ordeal, if you don’t eat the wrong plant. You must therefore learn as much as possible beforehand about the flora of the region where you will be operating. Plants can provide you with medicines in a survival situation. Plants can supply you with weapons and raw materials to construct shelters and build fires. Plants can even provide you with chemicals for poisoning fish, preserving animal hides, and for camouflaging yourself and your equipment.

Note: You will find illustrations of the plants described in this chapter in Appendixes B and C.

Plants are valuable sources of food because they are widely available, easily procured, and, in the proper combinations, can meet all your nutritional needs.

Absolutely identify plants before using them as food. Poison hemlock has killed people who mistook it for its relatives, wild carrots and wild parsnips.

At times you may find yourself in a situation for which you could not plan. In this instance you may not have had the chance to learn the plant life of the region in which you must survive. In this case you can use the Universal Edibility Test to determine which plants you can eat and those to avoid.

It is important to be able to recognize both cultivated and wild edible plants in a survival situation. Most of the information in this chapter is directed towards identifying wild plants because information relating to cultivated plants is more readily available.

Remember the following when collecting wild plants for food:

• Plants growing near homes and occupied buildings or along roadsides may have been sprayed with pesticides. Wash them thoroughly. In more highly developed countries with many automobiles, avoid roadside plants, if possible, due to contamination from exhaust emissions.

• Plants growing in contaminated water or in water containing Giardia lamblia and other parasites are contaminated themselves. Boil or disinfect them.

• Some plants develop extremely dangerous fungal toxins. To lessen the chance of accidental poisoning, do not eat any fruit that is starting to spoil or showing signs of mildew or fungus.

• Plants of the same species may differ in their toxic or subtoxic compounds content because of genetic or environmental factors. One example of this is the foliage of the common chokecherry. Some chokecherry plants have high concentrations of deadly cyanide compounds while others have low concentrations or none. Horses have died from eating wilted wild cherry leaves. Avoid any weed, leaves, or seeds with an almondlike scent, a characteristic of the cyanide compounds.

• Some people are more susceptible to gastric distress (from plants) than others. If you are sensitive in this way, avoid unknown wild plants. If you are extremely sensitive to poison ivy, avoid products from this family, including any parts from sumacs, mangoes, and cashews.

• Some edible wild plants, such as acorns and water lily rhizomes, are bitter. These bitter substances, usually tannin compounds, make them unpalatable. Boiling them in several changes of water will usually remove these bitter properties.

• Many valuable wild plants have high concentrations of oxalate compounds, also known as oxalic acid. Oxalates produce a sharp burning sensation in your mouth and throat and damage the kidneys. Baking, roasting, or drying usually destroys these oxalate crystals. The corm (bulb) of the jack-in-the-pulpit is known as the “Indian turnip,” but you can eat it only after removing these crystals by slow baking or by drying.

You identify plants, other than by memorizing particular varieties through familiarity, by using such factors as leaf shape and margin, leaf arrangements, and root structure.

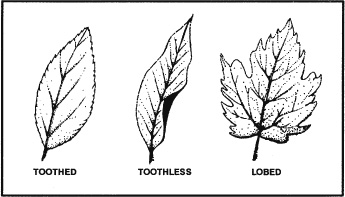

The basic leaf margins are toothed, lobed, and toothless or smooth.

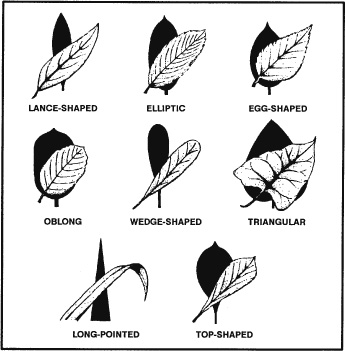

These leaves may be lance-shaped, elliptical, egg-shaped, oblong, wedge-shaped, triangluar, long-pointed, or top-shaped.

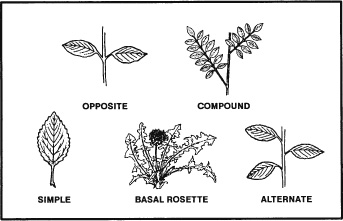

The basic types of leaf arrangements are opposite, alternate, compound, simple, and basal rosette.

Leaf margins.

Leaf shapes.

Leaf arrangements.

Root structures.

The basic types of root structures are the bulb, clove, taproot, tuber, rhizome, corm, and crown. Bulbs are familiar to us as onions and, when sliced in half, will show concentric rings. Cloves are those bulblike structures that remind us of garlic and will separate into small pieces when broken apart. This characteristic separates wild onions from wild garlic. Taproots resemble carrots and may be single-rooted or branched, but usually only one plant stalk arises from each root. Tubers are like potatoes and daylilies and you will find these structures either on strings or in clusters underneath the parent plants. Rhizomes are large creeping rootstocks or underground stems and many plants arise from the “eyes” of these roots. Corms are similar to bulbs but are solid when cut rather than possessing rings. A crown is the type of root structure found on plants such as asparagus and looks much like a mophead under the soil’s surface.

Learn as much as possible about plants you intend to use for food and their unique characteristics. Some plants have both edible and poisonous parts. Many are edible only at certain times of the year. Others may have poisonous relatives that look very similar to the ones you can eat or use for medicine.

There are many plants throughout the world. Tasting or swallowing even a small portion of some can cause severe discomfort, extreme internal disorders, and even death. Therefore, if you have the slightest doubt about a plant’s edibility, apply the Universal Edibility Test before eating any portion of it.

Before testing a plant for edibility, make sure there are enough plants to make the testing worth your time and effort. Each part of a plant (roots, leaves, flowers, and so on) requires more than 24 hours to test. Do not waste time testing a plant that is not relatively abundant in the area.

Remember, eating large portions of plant food on an empty stomach may cause diarrhea, nausea, or cramps. Two good examples of this are such familiar foods as green apples and wild onions. Even after testing plant food and finding it safe, eat it in moderation.

You can see from the steps and time involved in testing for edibility just how important it is to be able to identify edible plants.

To avoid potentially poisonous plants, stay away from any wild or unknown plants that have—

• Milky or discolored sap.

• Beans, bulbs, or seeds inside pods.

• Bitter or soapy taste.

• Spines, fine hairs, or thorns.

• Dill, carrot, parsnip, or parsleylike foliage.

• “Almond” scent in woody parts and leaves.

• Grain heads with pink, purplish, or black spurs.

• Three-leaved growth pattern.

Using the above criteria as eliminators when choosing plants for the Universal Edibility Test will cause you to avoid some edible plants. More important, these criteria will often help you avoid plants that are potentially toxic to eat or touch.

An entire encyclopedia of edible wild plants could be written, but space limits the number of plants presented here. Learn as much as possible about the plant life of the areas where you train regularly and where you expect to be traveling or working. Listed below and on the following pages are some of the most common edible and medicinal plants.

TEMPERATE ZONE FOOD PLANTS

• Amaranth (Amaranthus retroflexus and other species)

• Arrowroot (Sagittaria species)

• Asparagus (Asparagus officinalis)

• Beechnut (Fagus species)

• Blackberries (Rubus species)

• Blueberries (Vaccinium species)

• Burdock (Arctium lappa)

• Cattail (Typha species)

• Chestnut (Castanea species)

• Chicory (Cichorium intybus)

• Chufa (Cyperus esculentus)

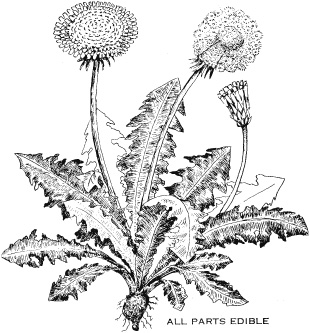

• Dandelion (Taraxacum officinale)

Dandelion

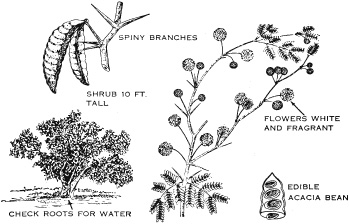

Acacia

• Daylily (Hemerocallis fulva)

• Nettle (Urtica species)

• Oaks (Quercus species)

• Persimmon (Diospyros virginiana)

• Plantain (Plantago species)

• Pokeweed (Phytolacca americana)

• Prickly pear cactus (Opuntia species)

• Purslane (Portulaca oleracea)

• Sassafras (Sassafras albidum)

• Sheep sorrel (Rumex acetosella)

• Strawberries (Fragaria species)

• Thistle (Cirsium species)

• Water lily and lotus (Nuphar, Nelumbo, and other species)

• Wild onion and garlic (Allium species)

• Wild rose (Rosa species)

• Wood sorrel (Oxalis species)

TROPICAL ZONE FOOD PLANTS

• Bamboo (Bambusa and other species)

• Bananas (Musa species)

• Breadfruit (Artocarpus incisa)

• Cashew nut (Anacardium occidentale)

• Coconut (Cocos nucifera)

• Mango (Mangifera indica)

• Palms (various species)

• Papaya (Carica species)

• Sugarcane (Saccharum officinarum)

• Taro (Colocasia species)

DESERT ZONE FOOD PLANTS

• Acacia (Acacia farnesiana)

• Agave (Agave species)

• Cactus (various species)

• Date palm (Phoenix dactylifera)

• Desert amaranth (Amaranthus palmeri)

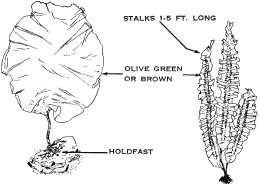

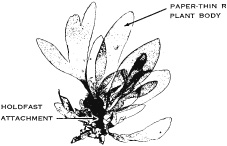

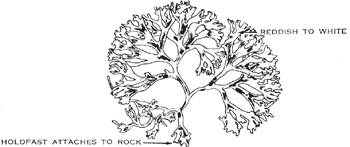

One plant you should never overlook is seaweed. It is a form of marine algae found on or near ocean shores. There are also some edible fresh-water varieties. Seaweed is a valuable source of iodine, other minerals, and vitamin C. Large quantities of seaweed in an unaccustomed stomach can produce a severe laxative effect.

Dulse.

Sugar wrack.

Laver.

Irish moss.

Kelp.

When gathering seaweeds for food, find living plants attached to rocks or floating free. Seaweed washed onshore any length of time may be spoiled or decayed. You can dry freshly harvested seaweeds for later use.

Its preparation for eating depends on the type of seaweed. You can dry thin and tender varieties in the sun or over a fire until crisp. Crush and add these to soups or broths. Boil thick, leathery seaweeds for a short time to soften them. Eat them as a vegetable or with other foods. You can eat some varieties raw after testing for edibility.

SEAWEEDS

• Dulse (Rhodymenia palmata)

• Green seaweed (Ulva lactuca)

• Irish moss (Chondrus crispus)

• Kelp (Alaria esculenta)

• Laver (Porphyra species)

• Mojaban (Sargassum fulvellum)

• Sugar wrack (Laminaria saccharina)

Although some plants or plant parts are edible raw, you must cook others to be edible or palatable. Edible means that a plant or food will provide you with necessary nutrients, while palatable means that it actually is pleasing to eat. Many wild plants are edible but barely palatable. It is a good idea to learn to identify, prepare, and eat wild foods.

Methods used to improve the taste of plant food include soaking, boiling, cooking, or leaching. Leaching is done by crushing the food (for example, acorns), placing it in a strainer, and pouring boiling water through it or immersing it in running water.

Boil leaves, stems, and buds until tender, changing the water, if necessary, to remove any bitterness.

Boil, bake, or roast tubers and roots. Drying helps to remove caustic oxalates from some roots like those in the Arum family.

Leach acorns in water, if necessary, to remove the bitterness. Some nuts, such as chestnuts, are good raw, but taste better roasted.

You can eat many grains and seeds raw until they mature. When hard or dry, you may have to boil or grind them into meal or flour.

The sap from many trees, such as maples, birches, walnuts, and sycamores, contains sugar. You may boil these saps down to a syrup for sweetening. It takes about 35 liters of maple sap to make one liter of maple syrup!

—From Survival (Field Manual 21–70)

Bradford Angier

(Quercus)

There is no need for anyone to starve where acorns abound, and from 200 to 500 oaks (botanists differ) grow in the world. Some eighty-five of these are native to the United States. Although some of the latter species are scrubby, the genus includes some of our biggest and most stately trees. Furthermore, except in our northern prairies, oaks are widely distributed throughout the contiguous states, thriving at various altitudes and in numerous types of soil.

Abundant and substantial, acorns are perhaps this country’s most important wildlife food. The relatively tiny acorns of the willow oak, pin oak, and water oak are often obtainable near streams and ponds, where they are relished by mallards, wood ducks, pintails, and other waterfowl. Quail devour such small acorns and peck the kernels out of the larger nuts.

Pheasants, grouse, pigeons, doves, and prairie chickens enjoy the nuts as well as the buds. Wild turkeys gulp down whole acorns regardless of their size. Squirrels and chipmunks are among the smaller animals storing acorns for off-season use. Black-tailed mule and white-tailed deer, elk, peccaries, and mountain sheep enjoy the acorns and also browse on twigs and foliage. Black bears grow fat on acorns.

Acorns probably rated the top position on the long list of wild foods depended on by the Indians. It has been stated, for example, that acorn soup, or mush, was the chief daily food of more than three-quarters of the native Californians. The eastern settlers were early introduced to acorns, too. In 1620 during their first hungry winter in Plymouth, the Pilgrims were fortunate enough to discover baskets of roasted acorns which the Indians had buried in the ground. In parts of Mexico and in Europe, the natives today still use acorns in the old ways.

All acorns are good to eat. Some are less sweet than others, that’s all. But the bitterness that is prevalent in different degrees is due to tannin, the same ingredient that causes tea to be bitter. Although it is not digestible in large amounts, it is soluble in water. Therefore, even the bitterest acorns can be made edible in an emergency.

Oaks comprise the most important group of hardwood timber trees on this continent. A major proportion of our eastern forests is oak. Its dense, durable wood has many commercial uses. Furthermore, oaks are among the most popular shade trees along our streets and about our dwellings.

The oaks may be separated into two great groups: the white oaks and the red oaks. The acorns of the former are the sweet ones. They mature in one growing season. The inner surfaces of the shells are smooth. The leaves typically have rounded lobes, but they are never bristle-tipped. The bark is ordinarily grayish and is generally scaly.

Among the red oaks, the usually bitter acorns do not mature until the end of the second growing season. The inner surfaces of the shells are customarily coated with woolly hair. The leaves have distinct bristles at their tips or at the tops of their lobes. The typically dark bark is ordinarily furrowed.

Indians used acorns both by themselves and in combination with other foods. For example, the Digger Indians roasted their acorns from the western white oak, Quercus lobata, hulled them, and ground them into a coarse meal which they formed into cakes and baked in crude ovens. In the East, the acorns of the white oak, Quercus alba, were also ground into meal but then were often mixed with the available cornmeal before being shaped into cakes and baked. Roasted and ground white oak acorns provide one of the wilderness coffees.

Eastern white oak.

Indians leached their bitter acorns in a number of ways. Sometimes the acorns would be buried in swamp mud for a year, after which they would be ready for roasting and eating whole. Other tribes let their shelled acorns mold in baskets, then buried them in clean freshwater sand. When they had turned black, they were sweet and ready for use.

Some tribes ground their acorns by pounding them in stone pestles, many of which are found today, and then ran water through the meal by one method or another for often the greater part of a day until it was sweet. The meal might be placed in a specially woven basket for this purpose, or it might just be buried in the sandy bed of a stream.

To make the familiar, somewhat sweetish soup or gruel of the results, all that is necessary is to heat the meal in water. The Indians generally used no seasoning. As a matter of fact, until the white man came they ordinarily had no utensils but closely woven baskets. These were flammable, of course, and the heating had to be done by putting in rocks heated in campfires. Still showing how little one can get along with, the tribe then ate from common baskets, using their fingers.

It’s an easy thing to leach acorns today. Just shell your nuts and boil them whole in a kettle of water, changing the liquid every time it becomes yellowish. You can shorten the time necessary for this to as little as a couple of hours, depending of course on the particular acorns, if you keep a teakettle of water always heating on the stove while this process is continuing. The acorns can then be dried in a slow oven, with the door left ajar, and either eaten as is or ground into coarse bits for use like any other nuts or into a fine meal.

To make acorn cakes, mix 2 cups of the meal with ½ teaspoon salt and ¾ cup of water to form a stiff batter. This will be improved if you let it stand at room temperature for about an hour before turning it into the skillet.

Heat 3 tablespoons cooking oil in a large frypan until a test drop of water will sizzle. Drop the batter from a tablespoon, using a greased spatula to shape cakes a bit over 3 inches in diameter. Reduce the heat and tan the cakes slowly on each side. They are good either hot or cold.

For acorn pancakes for two, combine a cup of acorn meal and a cup of regular flour with 2 tablespoons sugar, 3 teaspoons double-action baking powder, and ½ teaspoon salt. Beat 2 eggs, 1 ½ cups milk, and 2 tablespoons liquid shortening. Get your preferably heavy frypan or griddle hot, short of smoking temperature, and grease it sparingly with bacon.

When everything is ready to go, mix the whole business very briefly into a thin batter. Overmixing will make these tough. For this reason, a slightly lumpy batter is preferable to one that’s beaten smooth. Turn each hotcake only once, when the flapjack starts showing small bubbles. The second side will take only half as long to cook. Serve steaming hot with butter or margarine and sugar, maple syrup, or one of the wild jellies.

We think of antibiotics as modern developments, but some of the Indian tribes used to let their acorn meal accumulate a mold. This was scraped off, kept in a damp place, and used to treat sores and inflammations.

(Betula)

The nutritious bark of the black birch is said to have probably saved the lives of scores of Confederate soldiers during Garnett’s retreat over the mountains to Monterey, Virginia. For years afterward, the way the soldiers went could be followed by the peeled birch trees.

The black birch may be identified at all times of the year by its tight, reddish-brown, cherrylike bark, which has the aroma and flavor of wintergreen. Smooth in young trees, this darkens and separates into large, irregular sections as these birches age. The darkly dull green leaves, paler and yellower beneath, are two to four inches long, oval to oblong, short-stemmed, silky when young, smooth when mature, with double-toothed edges. They give off an odor of wintergreen when bruised. The trees have both erect and hanging catkins, on twigs that also taste and smell like wintergreen.

Black birch.

In fact, when the commercial oil of wintergreen is not made synthetically, it is distilled from the twigs and bark of the black birch. This oil is exactly the same as that from the little wintergreen plant, described earlier.

Black birches enhance the countryside from New England to Ontario, south to Ohio and Delaware, and along the Appalachian Mountains to Georgia and Alabama.

A piquant tea, brisk with wintergreen, is made from the young twigs, young leaves, the thick inner bark, and the bark from the larger roots. This latter reddish bark, easily stripped off in the spring and early summer, can be dried at room temperatures and stored in sealed jars in a cool place for later use. A teaspoon to a cup of boiling water, set off the heat and allowed to steep for 5 minutes, makes a tea that is delicately spicy. Milk and sugar make it even better. As a matter of fact, any of the birches make good tea.

You can make syrup and sugar from the sap, too, as from the sap of all birches. I’ll never forget my first introduction to this. It was our first spring in the paper birch country of the Far North, and Vena and I were bemoaning the fact that there were no maples from which to tap sap for our sourdough pancakes.

“Birch syrup you can get here in copious amounts,” Dudley Shaw, a trapper and our nearest neighbor, informed Vena. “Heavenly concoction. It’ll cheer Brad up vastly.”

“Oh, will you show me how?”

“I’ll stow a gimlet in my pack when I prowl up this way the first of the week to retrieve a couple of traps that got frozen in,” Dudley agreed. “Noble lap, birch syrup is. Glorious in flippers.”

Dudley told us to get some containers. Lard pails would do, he said, or we could attach some wire bails through nail holes in the tops of several tomato cans. He beamed approval when he arrived early Tuesday morning. The improvised sap buckets, suspended on nails driven above the small holes Dudley bored with his gimlet, caught a dripping flow of watery fluid.

“You’d better ramble out this way regularly to see these don’t overflow,” Dudley cautioned. “Keep the emptied sap simmering cheerfully on the back of the stove. Tons of steam have to come off.”

“Will it hurt the trees any?” Vena asked anxiously.

“No, no,” Dudley said reassuringly. “The plunder will begin to bog down when the day cools, anyway. Then we’ll whittle out pegs and drive them in to close the blinking holes. Everything will be noble.”

Everything was, especially the birch syrup. It wasn’t as thick as it might have been, even after all that boiling. There was a distressingly small amount of it, too. But what remained from the day’s work was sweet, spicy, and poignantly delicious. What we drank beforehand, too, was refreshing, sweet, and provocatively spicy.

All the birches furnish prime emergency food. Two general varieties of the trees grow across the continent, the black birch and those similar to it, and the familiar white birches whose cheerful foliage and softly gleaming bark lighten the northern forests. Layer after layer of this latter bark can be easily stripped off in great sheets, although because of the resulting disfigurement this shouldn’t be done except in an emergency, and used to start a campfire in any sort of weather.

The inner bark, dried and then ground into flour, has often been used by Indians and frontiersmen for bread. It is also cut into strips and boiled like noodles in stews. But you don’t need to go even to that much trouble. Just eat it raw.

(Arctium)

This member of the thistle family marched across Europe with the Roman legions, sailed to the New World with the early settlers, and the now thrives throughout much of the Unites States and southern Canada. A topnotch wild food, it has the added advantages of being familiar and of not being easily mistaken.

The somewhat unpleasant associations with its name are, at the same time, a disadvantage when it comes to bringing this aggressive but delicious immigrant to the table. Muskrats are sold in some markets as swamp rabbits, while crows find buyers as rooks. But unfortunately in this country burdock is usually just burdock, despite the fact that varieties of it are especially cultivated as prized domestic vegetables in Japan and elsewhere in the Eastern Hemisphere.

Burdock is found almost everywhere it can be close to people and domestic animals—along roads, fences, stone walls, and in yards, vacant lots, and especially around old barns and stables. Its sticky burrs, which attach themselves cosily to man and beast, are familiar nuisances.

Burdock.

The burdock is a coarse biennial weed which, with its branches, rapidly grows to from two to six feet high. The large leaves, growing on long stems, are shaped something like oblong hearts and are rough and purplish with veins. Tiny, tubular, usually magenta flowers appear from June to November, depending on the locality, the second year. These form the prickly stickers, which actually, of course, are the seed pods.

No one need stay hungry very long where the burdock grows, for this versatile edible will furnish a number of different delicacies. It is for the roots, for instance, that they are grown by Japanese throughout the Orient. Only the first-year roots should be used, but these are easy to distinguish as the biennials stemming from them have no flower and burr stalks. We get all we can use from the sides of our horses’ corral, where they are easily disengaged. When found in hard ground, however, the deep, slender roots are harder to come by, although they are worth quite a bit of effort.

The tender pith of the root, exposed by peeling, will make an unusually good potherb if sliced like parsnips and simmered for 20 minutes in water to which about ¼ teaspoon baking soda has been added. Then drain, barely cover with fresh boiling water, add a teaspoon of salt, and cook until tender. Serve with butter or margarine spreading on top.

If caught early enough, the young leaves can be boiled in 2 waters and served as greens. If you’re hungry, the peeled young leaf stalks are good raw, especially with a little salt. These are also added to green salads and to vegetable soups and are cooked by themselves like asparagus.

It is the rapidly growing flower stalk that furnishes one of the tastier parts of the burdock. When these sprout up the second year, watch them so that you can cut them off just as the blossom heads are starting to appear in late spring or early summer. Every shred of the strong, bitter skin must be peeled off. Then cook the remaining thick, succulent interiors in 2 waters, as you would the roots, and serve hot with butter or margarine.

The pith of the flower stalks has long been used, too, for a candy. One way to make this is by cutting the whitish cores into bite-size sections. Boil these for 15 minutes in water to which ¼ teaspoon baking soda has been added. Drain. Heat what you judge to be an approximately equal weight of sugar in enough hot water to dissolve it, and then add the juice of an orange. Put in the burdock pieces, cook slowly until the syrup is nearly evaporated, drain, and roll in granulated sugar. This never lasts for very long.

The first-year roots, dug either in the fall or early spring, are also used back of beyond as a healing wash for burns, wounds, and skin irritations. One way to make this is by dropping 4 teaspoons of the root into a quart of boiling water and allowing this to stand until cool.

(Juglans)

Confederate soldiers and partisans were referred to as butternuts during the Civil War because of the brown homespun clothes of the military, often dyed with the green nut husks and the inner bark of these familiar trees. Some of the earliest American settlers made the same use of them. As far back as the Revolution, a common laxative was made of the inner bark, a spoonful of finely cut pieces to a cup of boiling water, drunk cold. Indians preceded the colonists in boiling down the sap of this tree, as well as that of the black walnut, to make syrup and sugar, sometimes mixing the former with maple syrup.

The butternut thrives in chillier climates than does the black walnut, ranging higher in the mountains and further north. Otherwise, this tree, also known as white walnut and oilnut, closely resembles its cousin except for being smaller and lighter colored. Its wood is comparatively soft, weak, and light, although still close-grained. The larger trees, furthermore, are nearly always unsound.

Butternuts grow from the Maritime Provinces to Ontario, south to the northern mountainous regions of Georgia and Alabama, and west to Arkansas, Kansas, and the Dakotas. They are medium-sized trees, ordinarily from about thirty to fifty feet high, with a trunk diameter of up to three feet. Some trees, though, tower up to ninety feet or more. The furrowed and broadly ridged bark is gray.

Butternut.

The alternate compound leaves are from fifteen to thirty inches long. Each one is made up of eleven to seventeen lance-shaped, nearly stemless leaflets, two to six inches long and about half as broad, with sharply pointed tips, sawtoothed edges, and unequally rounded bases. Yellowish green on top, these are paler and softly downy underneath. The catkins and the shorter flower spikes appear in the spring when the leaves are about half grown.

The nuts are oblong rather than round, blunt, about two to two and a half inches long, and a bit more than half as thick. Thin husks, notably sticky and coated with matted rusty hairs, enclose the nuts whose bony shells are roughly ridged, deeply furrowed, and hard. Frequently growing in small clusters of two to five, these ripen in October and soon drop from the branches.

The young nuts, when they have nearly reached their full size, can be picked green and used for pickles which bring out the flavor of meat like few other things and which really attract notice as hors d’oeuvres. If you can still easily shove a large needle through the nuts, it is not too late to pickle them, husks and all, after they have been scalded and the outer fuzz rubbed off.

Put them in a strong brine for a week, changing the water every other day and keeping them tightly covered. Then drain and wipe them. Pierce each nut all the way through several times with a large needle. Then put them in glass jars with a sprinkling of powdered ginger, nutmeg, mace, and cloves between each layer. Bring some good cider vinegar to a boil, immediately fill each jar, and seal. You can start enjoying this unusual delicacy in two weeks.

A noteworthy dessert can be made with butternuts by mixing ½ cup of the broken meats with 1 cup diced dates, 1 cup sugar, 1 teaspoon baking powder, and ⅛ teaspoon salt. Beat 4 egg whites until they are stiff and fold them into the above mixture. Bake in a greased pan in a slow oven for 20 minutes. Serve either hot or cold with whipped cream. This is also good, particularly when hot, with liberal scoops of vanilla ice cream.

Butternut and date pie is something special. Chop a cup apiece of dates and nuts. Roll a dozen ordinary white crackers into small bits, too. Mix with 1 cup sugar and ½ teaspoon baking powder. Then beat 3 egg whites until they are stiff. Sometimes, if the nuts are not as tasty as usual, we also add a teaspoon of almond extract. In either event, fold into the nut mixture and pour into a buttered 9-inch pie pan. Bake ½ hour, or until light brown, in a moderate oven. Cool before cutting. Ice or whipped cream is good with this, too, but it is also delicately tasty alone.

Butternut brownies, eaten by the nibble and washed down with draughts of steaming black tea, are one of the ways I like to top off my noonday lunches when hunting in the late fall. Just blend together 1 cup sugar, 1 teaspoon salt, ½ cup melted butter or margarine, 2 squares bitter chocolate, 1 teaspoon vanilla, and 3 eggs. When this is thoroughly mixed, stir into it 1 cup finely broken butternuts and ½ cup flour. Pour into a shallow greased pan and bake in a moderate oven 20 minutes.

(Typhaceae)

Who does not know these tall strap-leaved plants with their brown sausagelike heads which, growing in large groups from two to nine feet high, are exclamation points in wet places throughout the temperate and tropical countries of the world?

Although now relatively unused in the United States, where four species thrive, cattails are deliciously edible both raw and cooked from their starchy roots to their cornlike spikes, making them prime emergency foods. Furthermore, the long slender basal leaves, dried and then soaked to make them pliable, provide rush seating for chairs, as well as tough material for mats. As for the fluff of light-colored seeds, which enliven many a winter wind, these will softly fill pillows and provide warm stuffing for comforters.

Cattail

Left: leaves, head, and flower spike.

Right: basal leaves and root.

Cattails are also known in some places as rushes, cossack asparagus, bulrushes, cat-o’nine-tails, and flags. Sure signs of fresh or brackish water, they are tall, stout-stemmed perennials with thin, stiff, swordlike, green leaves up to six feet long. These have well-developed, round rims at the sheathing bases.

The branched rootstocks creep in crossing tangles a few inches below the usually muddy surface. The flowers grow densely at the tops of the plants in spikes which, first plumply green and finally a shriveling yellow, resemble long bottle brushes and eventually produce millions of tiny, wind-wafted seeds.

These seeds, it so happens, are too small and hairy to be very attractive to birds except to a few like the teal. It is the starchy underground stems that attract such wildlife as muskrat and geese. Too, I’ve seen moose dipping their huge, ungainly heads where cattails grow.

Another name for this prolific wild edible should be wild corn. Put on boots and have the fun of collecting a few dozen of the greenish yellow flower spikes before they start to become tawny with pollen. Husk off the thin sheaths and, just as you would with the garden vegetable, put while still succulent into rapidly boiling water for a few minutes until tender. Have plenty of butter or margarine by each plate, as these will probably be somewhat roughly dry, and keep each hot stalk liberally swabbed as you feast on it. Eat like corn. You’ll end up with a stack of wiry cobs, feeling deliciously satisfied.

Some people object to eating corn on the cob, too, especially when there is company. This problem can be solved by scraping the boiled flower buds from the cobs, mixing 4 cups of these with 2 cups buttered bread crumbs, 2 well-beaten eggs, 1 teaspoon salt, ⅛ teaspoon pepper, and a cup of rich milk. Pour into a casserole, sprinkle generously with paprika, and heat in a moderate oven 15 minutes.

These flower spikes later become profusely golden with thick yellow pollen which, quickly rubbed or shaken into pails or onto a cloth, is also very much edible. A common way to take advantage of this gilded substance, which can be easily cleaned by passing it through a sieve, is by mixing it half and half with regular flour in breadstuffs.

For example, the way to make pleasingly golden cattail pancakes for 4 is by sifting together 1 cup pollen, 1 cup flour, 2 teaspoons baking powder, 2 tablespoons sugar, and ½ teaspoon salt. Beat 2 eggs and stir them into 1 ⅓ cups milk, adding 2 tablespoons melted butter or margarine. Then rapidly mix the batter. Pour at once in cakes the size of saucers onto a sparingly greased griddle, short of being smoking hot. Turn each flapjack only once, when the hot cake starts showing small bubbles. The second side takes only about half as long to cook. Serve steaming hot with butter and sugar, with syrup, or with what you will.

It is the tender white insides of about the first 1 or 1 ½ feet of the peeled young stems that, eaten either raw or cooked, lends this worldwide delicacy its name of cossack asparagus. These highly eatable aquatic herbs can thus be an important survival food in the spring.

Later on, in the fall and winter, quantities of the nutritiously starchy roots can be dug and washed, peeled white still wet, dried, and then ground into a meal which can be sifted to get out any fibers. Too, there is a pithy little tidbit where the new stems sprout out of the rootstocks that can be roasted or boiled like young potatoes. All in all, is it any wonder that the picturesque cattails, now too often neglected except by nesting birds, were once an important Indian food?

(Prunus)

Perhaps the most widely distributed tree on this continent, the chokecherry grows from the Arctic Circle to Mexico and from ocean to ocean. Despite their puckery quality, one handful of the small ripe berries seems to call for another when you’re hot and thirsty. The fruit, which is both red or black, also makes on enjoyable tart jelly.

Often merely a large shrub, the chokecherry also becomes a small tree up to twenty-five feet tall with a trunk about eight inches through. It is found in open woods, but is more often seen on streambanks, in thickets in the corners of fields, and along roadsides and fences. Although the wood is similar to that of the rum cherry, it has no commercial value because of its smallness.

Chokecherry leaves, from two to four inches long and about half as wide, are oval or inversely ovate, with abrupt points. They are thin and smooth, dull dark green above and paler below. The edges are finely indented with narrowly pointed teeth. The short stems, less than an inch in length, have a pair of glands at their tops. The long clusters of flowers blossom when the leaves are nearly grown. The red to black fruits, the size of peas, are frequently so abundant that the limbs bend under their weight.

Chokecherry

Left: flowering branch. Center: branch with leaves and fruit.

Right: winter twig

An attractive and tasty jelly is made by adding 2 parts of cooked applejuice to 1 part of cooked chokecherry juice and proceeding as with rum cherry jelly. Too, a pure version can also be prepared with the help of commercial pectin.

Any of these tart wild cherry jellies can be used to flavor pies. Start by lightly beating 3 eggs. Mix 1 cup sugar, ¼ teaspoon salt, and ¼ teaspoon nutmeg, and add slowly to the eggs, continuing to beat. Melt ½ cup of butter or margarine and add that, too. Then thoroughly stir in 1 tablespoon of your jelly. Pour into an unbaked pie crust. Place in a preheated moderate oven for 10 minutes. Then reduce the heat to slow for 15 minutes, or until it firms.

(Cyperus)

Chufa was so valued as a nutriment during early centuries that as long as 4,000 years ago the Egyptians were including it among the choice foods placed in their tombs. Wildlife was enjoying it long before that. Both the edible tubers of this plant, also known as earth almond and as nut grass, and the seeds are sought by waterfowl, upland game birds, and other wildlife. Often abundant in mud flats that glisten with water in the late fall and early winter, the nutritious tubers are readily accessible to duck. Where chufa occurs as a robust weed in other places, especially in sandy soil and loam, upland game birds and rodents are seen vigorously digging for the tubers.

Abounding from Mexico to Alaska, and from one coast to the other, this edible sedge also grows in Europe, Asia, and Africa, being cultivated in some localities for its tubers. Sweet, nutty, and milky with juice, these are clustered about the base of the plant, particularly when it grows in sandy or loose soil where a few tugs will give a hungry man his dinner. In hard dirt, the nuts are widely scattered as well as being difficult to excavate. Except for several smaller leaves at the top of the stalk supporting the flower clusters, all the light green, grasslike leaves of the chufa grow from the roots. These latter are comprised of long runners, terminating in little nutlike tubers. The numerous flowers grow in little, flat, yellowish spikes.

Chufa.

Chufa furnishes one of the wild coffees. Just separate the little tubers from their roots, wash them, and spread them out to dry. Then roast them in an oven with the door ajar until they are rich brown throughout, grind them as in the blender, and brew and serve like the store-bought beverage. So prepared, chufa tastes more like a cereal “coffee” than like the regular brew. But it is wholesome, pleasant, and it contains none of the sleep-retarding ingredients of the commercial grinds.

All you have to do is wash and eat chufas, but if you are going to have a wild-foods dinner for guests, why not go one step further and have some really different chips to serve with your dip during the cocktail hour? The chufas first have to be very well dried, as in a slow oven, then ground to powder as in the ubiquitous blender. This powder can be mixed with regular wheat flour for all sorts of appetizing vitamin-and-mineral-rich cakes, breads, and cookies.

For these chips, which resemble fat little pillows, sift together a cup of powdered chufa, a cup of all-purpose flour, 3 teaspoons baking powder, and a teaspoon of salt. Then cut in 2 tablespoons of shortening with a pastry blender or a pair of knives. Not wasting any time, work in ¾ cup of cold water bit by bit to make your dough. Roll this out as thinly as you can. Cut into 2-inch squares and fry these one by one in hot fat. They’ll puff as they bronze. If you’ll turn them, the other side will expand, too. Drain the some 30 resulting chips on paper toweling. They are particularly tasty, by the way, in an avocado and tomato dip touched up with grated wild onion.

The Spanish make a refreshing cold drink from the chufa, enjoyed both as is and as a base for stronger concoctions. A popular alcoholic drink is made by partially freezing this beverage in the refrigerator, then adding an equal volume of light rum to make a sort of wild frozen Daiquiri. The Spanish recipe calls for soaking ½ pound of the well-washed tubers for 2 days. Then drain them and either mash them or put them through the blender along with 4 cups of water and ⅓ cup sugar. Strain the white, milky results, and you’re in business.

Europeans in the Mediterranean area, northward as far as Great Britain, used to make a conserve of chufa that is still very much worth the trouble. Again, begin by soaking the scrubbed tubers for 2 days in cold water. You’ll need a quart of the drained vegetables for this recipe.

Make a syrup by boiling together a cup of sugar, a cup of corn syrup, and 1⅔ cups of water for 10 minutes. Add the drained chufas. Simmer, stirring occasionally, until the tubers are tender and the syrup thickened. Then take off the stove. Cover and let stand overnight. The next day, reheat to boiling. Pack the chufas in hot, sterile pint jars. Bring the liquid once more to a boil and pour it over the chufas, filling the jars to within ½ inch of their tops. Seal at once, cover if necessary to protect from drafts, allow to cool, label, and store.

(Trifolium)

Everyone who as a youngster has sucked honey from the tiny tubular florets of its white, yellow, and reddish blossoms, or who has searched among its green beds for the elusive four-leaf combinations, knows the clover. Some seventy-five species of clover grow in this country, about twenty of them thriving in the East.

Clovers, which are avidly pollinated by bees, grow from an inch or so to two feet high in the fields, pastures, meadows, open woods, and along roadsides of the continent. Incidentally, when introduced into Australia, it failed to reproduce itself until bumblebees were also imported.

The stemmed foliage is usually composed of three small leaflets with toothed edges, although some of the western species boast as many as six or seven leaflets. This sweet-scented member of the pea family provides esteemed livestock forage. Red clover is Vermont’s state flower. White clover is all the more familiar for being grown in lawns. Quail are among the birds eating the small, hard seeds, while deer, mountain sheep, antelope, rabbit, and other animals browse on the plants.

Bread made from the seeds and dried blossoms of clover has the reputation of being very wholesome and nutritious and of sometimes being a mainstay in times of famine. Being so widely known and plentiful, clover is certainly a potential survival food that can be invaluable in an emergency.

The young leaves and flowers are good raw. Some Indians, eating them in quantity, used to dip these first in salted water. The young leaves and blossoms can also be successfully boiled, and they can be steamed as the Indians used to do before drying them for winter use.

Clover

If you’re steaming greens for 2 couples, melt 4 tablespoons of butter or margarine in a large, heavy frypan over high heat. Stir in 6 loosely packed cups of greens and blossoms, along with 6 tablespoons of water. Cover, except when stirring periodically, and cook for several minutes until the clover is wilted. Salt, pepper, and eat.

The sweetish roots may also be appreciated on occasion, some people liking them best when they have been dipped in oil or in meat drippings.

Clover tea is something you may very well enjoy. Gather the fullgrown flowers at a time when they are dry. Then further dry them indoors at ordinary house temperatures, afterwards rubbing them into small particles and sealing them in bottles or jars to hold in the flavor. Use 1 teaspoon of these to each cup of boiling water, brewing either in a teapot or in individual cups, as you would oriental tea.

(Caltha)

The glossy yellow flowers of the cowslip, also known as marsh marigold and by over two dozen other common names, are among the first to gleam in the spring along stream banks and in marshy coolnesses from Alaska to Newfoundland and as far south as Tennessee and South Carolina. This wild edible is also eagerly awaited in Europe.

One reason this member of the crowfoot family gained its name of cowslip is that you often see it growing in wet barnyards and meadows and in the trampled soggy ground where cattle drink. Few wild blossoms are more familiar or beautiful, and New Englanders find few wild greens that boil us so delicately so soon after the long, white winters.

The bright golden blossoms, which grow up to an inch and a half broad and which somewhat resemble large buttercups, have from five to nine petal-like divisions which do not last long, falling off and being replaced by clusters of seed-crammed pods. These flowers grow, singly and in groups, on slippery stems that lift hollowly among the leaves.

Cowslips, growing up to one and two feet tall, have crisp, shiny, heart-shaped lower leaves, some three to seven inches broad. These grow on long, fleshy stems. On the other hand, the upper leaves appear almost directly from the smooth stalks themselves. The leaf edges, sometimes wavy, frequently are divided into rounded segments.

There are two things to watch out for if you are going to enjoy the succulent cowslip. First, this plant must be served as a potherb, as the raw leaves contain the poison helleborin, which is destroyed by cooking. It is, therefore, a good idea to gather cowslips by themselves to avoid the mistake of mixing them with salad greens. Secondly, ordinary care must be taken not to include any of the easily differentiated poisonous hellebore or water hemlocks that sometimes grow in the same places.

The two poisonous plants are entirely different in appearance from the distinctive cowslip. The water hemlock plant superficially resembles the domestic carrot plant but has coarser leaves and a taller, thicker stem. The white hellebore, which can be mistaken for a loose-leaved cabbage, is a leafy plant which somewhat resembles skunk cabbage, one reason why that not altogether agreeable edible has been omitted from these pages.

Cowslip

The dark green leaves and thick, fleshy stems of the cowslip are at their tastiest before the plant flowers. The way many know them best is boiled for an hour in 2 changes of salted water, then lifted out in liberal forkfuls and topped with quickly spreading pads of butter.

For a change, you can cream them, too. Tear the cowslips into small pieces and boil for an hour in 2 changes of salted water. Then drain. In the meantime, be melting 3 tablespoons of butter or margarine, either in a saucepan over low heat or in the top of a double boiler. Stir in 3 tablespoons of flour and cook a minute. Then gradually add ½ cup of cream. Salt and pepper to taste, and stir until thickened. Add the cooked greens, mix well, and serve.

Parmesan cheese also goes well with cowslips on occasion. Just use the above recipe, adding 3 tablespoons of grated cheese after the flour and other ingredients have started to thicken. Then stir until the Parmesan has melted and the sauce is creamy.

The leaves and stems aren’t the only deli-ciously edible portions of this bright little harbinger of spring. You can make pickles from the buds, soaking them first for several hours in salted water, draining, and then simmering them in spiced vinegar, whereupon they take on the flavor of capers.

(Taraxacum)