The cyclic redundancy check, or CRC, is a technique for detecting errors in digital data, but not for making corrections when errors are detected. It is used primarily in data transmission. In the CRC method, a certain number of check bits, often called a checksum, or a hash code, are appended to the message being transmitted. The receiver can determine whether or not the check bits agree with the data to ascertain with a certain degree of probability that an error occurred in transmission. If an error occurred, the receiver sends a “negative acknowledgment” (NAK) back to the sender, requesting that the message be retransmitted.

The technique is also sometimes applied to data storage devices, such as a disk drive. In this situation each block on the disk would have check bits, and the hardware might automatically initiate a reread of the block when an error is detected, or it might report the error to software.

The material that follows speaks in terms of a “sender” and a “receiver” of a “message,” but it should be understood that it applies to storage writing and reading as well.

Section 14–2 describes the theory behind the CRC methodology. Section 14–3 shows how the theory is put into practice in hardware, and gives a software implementation of a popular method known as CRC-32.

There are several techniques for generating check bits that can be added to a message. Perhaps the simplest is to append a single bit, called the “parity bit,” which makes the total number of 1-bits in the code vector (message with parity bit appended) even (or odd). If a single bit gets altered in transmission, this will change the parity from even to odd (or the reverse). The sender generates the parity bit by simply summing the message bits modulo 2—that is, by exclusive or’ing them together. It then appends the parity bit (or its complement) to the message. The receiver can check the message by summing all the message bits modulo 2 and checking that the sum agrees with the parity bit. Equivalently, the receiver can sum all the bits (message and parity) and check that the result is 0 (if even parity is being used).

This simple parity technique is often said to detect 1-bit errors. Actually, it detects errors in any odd number of bits (including the parity bit), but it is a small comfort to know you are detecting 3-bit errors if you are missing 2-bit errors.

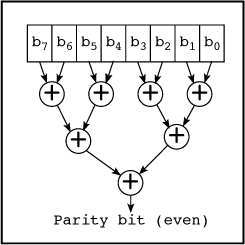

For bit serial sending and receiving, the hardware required to generate and check a single parity bit is very simple. It consists of a single exclusive or gate together with some control circuitry. For bit parallel transmission, an exclusive or tree may be used, as illustrated in Figure 14–1. Efficient ways to compute the parity bit in software are given in Section 5–2 on page 96.

FIGURE 14–1. Exclusive or tree.

Other techniques for computing a checksum are to form the exclusive or of all the bytes in the message, or to compute a sum with end-around carry of all the bytes. In the latter method, the carry from each 8-bit sum is added into the least significant bit of the accumulator. It is believed that this is more likely to detect errors than the simple exclusive or, or the sum of the bytes with carry discarded.

A technique that is believed to be quite good in terms of error detection, and which is easy to implement in hardware, is the cyclic redundancy check. This is another way to compute a checksum, usually eight, 16, or 32 bits in length, that is appended to the message. We will briefly review the theory, show how the theory is implemented in hardware, and then give software for a commonly used 32-bit CRC checksum.

We should mention that there are much more sophisticated ways to compute a checksum, or hash code, for data. Examples are the hash functions known as MD5 and SHA-1, whose hash codes are 128 and 160 bits in length, respectively. These methods are used mainly in cryptographic applications and are substantially more difficult to implement, in hardware and software, than the CRC methodology described here. However, SHA-1 is used in certain revision control systems (Git and others) as simply a check on data integrity.

The CRC is based on polynomial arithmetic, in particular, on computing the remainder when dividing one polynomial in GF(2) (Galois field with two elements) by another. It is a little like treating the message as a very large binary number, and computing the remainder when dividing it by a fairly large prime such as 232 – 5. Intuitively, one would expect this to give a reliable checksum.

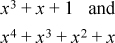

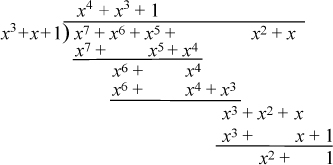

A polynomial in GF(2) is a polynomial in a single variable x whose coefficients are 0 or 1. Addition and subtraction are done modulo 2—that is, they are both the same as the exclusive or operation. For example, the sum of the polynomials

is x4 + x2 + 1, as is their difference. These polynomials are not usually written with minus signs, but they could be, because a coefficient of –1 is equivalent to a coefficient of 1.

Multiplication of such polynomials is straightforward. The product of one coefficient by another is the same as their combination by the logical and operator, and the partial products are summed using exclusive or. Multiplication is not needed to compute the CRC checksum.

Division of polynomials over GF(2) can be done in much the same way as long division of polynomials over the integers. Here is an example.

The reader may verify that the quotient x4 + x3 + 1 multiplied by the divisor x3 + x + 1, plus the remainder x2 + 1, equals the dividend.

The CRC method treats the message as a polynomial in GF(2). For example, the message 11001001, where the order of transmission is from left to right (110...), is treated as a representation of the polynomial x7 + x6 + x3 + 1. The sender and receiver agree on a certain fixed polynomial called the generator polynomial. For example, for a 16-bit CRC the CCITT (Le Comité Consultatif International Télégraphique et Téléphonique)1 has chosen the polynomial x16 + x12 + x5 + 1, which is now widely used for a 16-bit CRC checksum. To compute an r-bit CRC checksum, the generator polynomial must be of degree r. The sender appends r 0-bits to the m-bit message and divides the resulting polynomial of degree m + r – 1 by the generator polynomial. This produces a remainder polynomial of degree r – 1 (or less). The remainder polynomial has r coefficients, which are the checksum. The quotient polynomial is discarded. The data transmitted (the code vector) is the original m-bit message followed by the r-bit checksum.

There are two ways for the receiver to assess the correctness of the transmission. It can compute the checksum from the first m bits of the received data and verify that it agrees with the last r received bits. Alternatively, and following usual practice, the receiver can divide all the m + r received bits by the generator polynomial and check that the r-bit remainder is 0. To see that the remainder must be 0, let M be the polynomial representation of the message, and let R be the polynomial representation of the remainder that was computed by the sender. Then the transmitted data corresponds to the polynomial Mxr – R (or, equivalently, Mxr + R). By the way R was computed, we know that Mxr = QG + R, where G is the generator polynomial and Q is the quotient (that was discarded). Therefore the transmitted data, Mxr – R, is equal to QG, which is clearly a multiple of G. If the receiver is built as nearly as possible just like the sender, the receiver will append r 0-bits to the received data as it computes the remainder R. The received data with 0-bits appended is still a multiple of G, so the computed remainder is still 0.

That’s the basic idea, but in reality the process is altered slightly to correct for certain deficiencies. For example, the method as described is insensitive to the number of leading and trailing 0-bits in the data transmitted. In particular, if a failure occurred that caused the received data, including the checksum, to be all-0, it would be accepted.

Choosing a “good” generator polynomial is something of an art and beyond the scope of this text. Two simple observations: For an r-bit checksum, G should be of degree r, because otherwise the first bit of the checksum would always be 0, which wastes a bit of the checksum. Similarly, the last coefficient should be 1 (that is, G should not be divisible by x), because otherwise the last bit of the checksum would always be 0 (because Mxr = QG + R, if G is divisible by x, then R must be also). The following facts about generator polynomials are proved in [PeBr] and/or [Tanen]:

• If G contains two or more terms, all single-bit errors are detected.

• If G is not divisible by x (that is, if the last term is 1), and e is the least positive integer such that G evenly divides xe + 1, then all double errors that are within a frame of e bits are detected. A particularly good polynomial in this respect is x15 + x14 + 1, for which e = 32767.

• If x + 1 is a factor of G, all errors consisting of an odd number of bits are detected.

• An r-bit CRC checksum detects all burst errors of length ≤ r. (A burst error of length r is a string of r bits in which the first and last are in error, and the intermediate r – 2 bits may or may not be in error.)

The generator polynomial x + 1 creates a checksum of length 1, which applies even parity to the message. (Proof hint: For arbitrary k ≥ 0, what is the remainder when dividing xk by x + 1 ?)

It is interesting to note that if a code of any type can detect all double-bit and single-bit errors, then it can in principle correct single-bit errors. To see this, suppose data containing a single-bit error is received. Imagine complementing all the bits, one at a time. In all cases but one, this results in a double-bit error, which is detected. But when the erroneous bit is complemented, the data is error free, which is recognized. In spite of this, the CRC method does not seem to be used for single-bit error correction. Instead, the sender is requested to repeat the whole transmission if any error is detected.

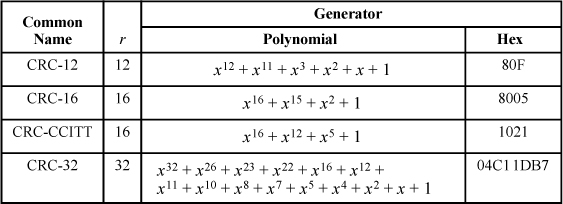

Table 14–1 shows the generator polynomials used by some common CRC standards. The “Hex” column shows the hexadecimal representation of the generator polynomial; the most significant bit is omitted, as it is always 1.

The CRC standards differ in ways other than the choice of generating polynomials. Most initialize by assuming that the message has been preceded by certain nonzero bits, others do no such initialization. Most transmit the bits within a byte least significant bit first, some most significant bit first. Most append the checksum least significant byte first, others most significant byte first. Some complement the checksum.

CRC-12 is used for transmission of 6-bit character streams, and the others are for 8-bit characters, or 8-bit bytes of arbitrary data. CRC-16 is used in IBM’s BISYNCH communication standard. The CRC-CCITT polynomial, also known as ITU-TSS, is used in communication protocols such as XMODEM, X.25, IBM’s SDLC, and ISO’s HDLC [Tanen]. CRC-32 is also known as AUTODIN-II and ITU-TSS (ITU-TSS has defined both 16- and a 32-bit polynomials). It is used in PKZip, Ethernet, AAL5 (ATM Adaptation Layer 5), FDDI (Fiber Distributed Data Interface), the IEEE-802 LAN/MAN standard, and in some DOD applications. It is the one for which software algorithms are given here.

The first three polynomials in Table 14–1 have x + 1 as a factor. The last (CRC-32) does not.

TABLE 14–1. GENERATOR POLYNOMIALS OF SOME CRC CODES

To detect the error of erroneous insertion or deletion of leading 0’s, some protocols prepend one or more nonzero bits to the message. These don’t actually get transmitted; they are simply used to initialize the key register (described below) used in the CRC calculation. A value of r 1-bits seems to be universally used. The receiver initializes its register in the same way.

The problem of trailing 0’s is a little more difficult. There would be no problem if the receiver operated by comparing the remainder based on just the message bits to the checksum received. But, it seems to be simpler for the receiver to calculate the remainder for all bits received (message and checksum), plus r appended 0-bits. The remainder should be 0. With a 0 remainder, if the message has trailing 0-bits inserted or deleted, the remainder will still be 0, so this error goes undetected.

The usual solution to this problem is for the sender to complement the checksum before appending it. Because this makes the remainder calculated by the receiver nonzero (usually), the remainder will change if trailing 0’s are inserted or deleted. How then does the receiver recognize an error-free transmission?

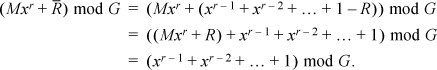

Using the “mod” notation for remainder, we know that

(Mxr + R) mod G = 0.

Denoting the “complement” of the polynomial R by  , we have

, we have

Thus, the checksum calculated by the receiver for an error-free transmission should be

(xr – 1 + xr – 2 + ... + 1) mod G.

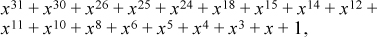

This is a constant (for a given G). For CRC-32 this polynomial, called the residual or residue, is

or hex C704DD7B [Black].

To develop a hardware circuit for computing the CRC checksum, we reduce the polynomial division process to its essentials.

The process employs a shift register, which we denote by CRC. This is of length r (the degree of G) bits, not r + 1 as you might expect. When the subtractions (exclusive or’s) are done, it is not necessary to represent the high-order bit, because the high-order bits of G and the quantity it is being subtracted from are both 1. The division process might be described informally as follows:

Initialize the CRC register to all 0-bits.

Get first/next message bit m.

If the high-order bit of CRC is 1,

Shift CRC and m together left 1 position, and XOR the result with the low-order r bits of G.

Otherwise,

Just shift CRC and m left 1 position.

If there are more message bits, go back to get the next one.

It might seem that the subtraction should be done first, and then the shift. It would be done that way if the CRC register held the entire generator polynomial, which in bit form is r + 1 bits. Instead, the CRC register holds only the low-order r bits of G, so the shift is done first, to align things properly.

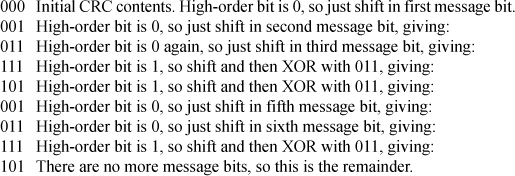

The contents of the CRC register for the generator G = x3 + x + 1 and the message M = x7 + x6 + x5 + x2 + x are shown below. Expressed in binary, G = 1011 and M = 11100110.

These steps can be implemented with the (simplified) circuit shown in Figure 14–2, which is known as a feedback shift register. The three boxes in the figure represent the three bits of the CRC register. When a message bit comes in, if the high-order bit (x2 box) is 0, simultaneously the message bit is shifted into the x0 box, the bit in x0 is shifted to x1, the bit in x1 is shifted to x2, and the bit in x2 is discarded. If the high-order bit of the CRC register is 1, then a 1 is present at the lower input of each of the two exclusive or gates. When a message bit comes in, the same shifting takes place, but the three bits that wind up in the CRC register have been exclusive or’ed with binary 011. When all the message bits have been processed, the CRC holds M mod G.

FIGURE 14–2. Polynomial division circuit for G = x3 + x + 1.

If the circuit of Figure 14–2 were used for the CRC calculation, then after processing the message, r (in this case 3) 0-bits would have to be fed in. Then the CRC register would have the desired checksum, Mxr mod G. There is a way to avoid this step with a simple rearrangement of the circuit.

Instead of feeding the message in at the right end, feed it in at the left end, r steps away, as shown in Figure 14–3. This has the effect of premultiplying the input message M by xr. But premultiplying and postmultiplying are the same for polynomials. Therefore, as each message bit comes in, the CRC register contents are the remainder for the portion of the message processed, as if that portion had r 0-bits appended.

FIGURE 14–3. CRC circuit for G = x3 + x + 1.

Figure 14–4 shows the circuit for the CRC-32 polynomial.

FIGURE 14–4. CRC circuit for CRC-32.

Figure 14–5 shows a basic implementation of CRC-32 in software. The CRC-32 protocol initializes the CRC register to all 1’s, transmits each byte least significant bit first, and complements the checksum. We assume the message consists of an integral number of bytes.

To follow Figure 14–4 as closely as possible, the program uses left shifts. This requires reversing each

message byte and positioning it at the left end of the 32-bit register, denoted byte in the program. The word-level reversing program shown in Figure 7–1 on page 129 can be used (although this is not very efficient, because we need to reverse only

eight bits).

The code of Figure 14–5 is shown for illustration only. It can be improved substantially while still retaining

its one-bit-at-a-time character. First, notice that the eight bits of the reversed

byte are used in the inner loop’s if-statement and then discarded. Also, the high-order eight bits of crc are not altered in the inner loop (other than by shifting). Therefore, we can set

crc = crc ^ byte ahead of the inner loop, simplify the if-statement, and omit the left shift of byte at the bottom of the loop.

The two reversals can be avoided by shifting right instead of left. This requires

reversing the hex constant that represents the CRC-32 polynomial and testing the least

significant bit of crc. Finally, the if-test can be replaced with some simple logic, to save branches. The result is shown

in Figure 14–6.

unsigned int crc32(unsigned char *message) {

int i, j;

unsigned int byte, crc;

i = 0;

crc = 0xFFFFFFFF;

while (message[i] != 0) {

byte = message[i]; // Get next byte.

byte = reverse(byte); // 32-bit reversal.

for (j = 0; j < = 7; j++) { // Do eight times.

if ((int)(crc ^ byte) < 0)

crc = (crc << 1) ^ 0x04C11DB7;

else crc = crc << 1;

byte = byte << 1; // Ready next msg bit.

}

i = i + 1;

}

return reverse(~crc);

}

FIGURE 14–5. Basic CRC-32 algorithm.

It is not unreasonable to unroll the inner loop by the full factor of eight. If this

is done, the program of Figure 14–6 executes in about 46 instructions per byte of input message. This includes a load and a branch. (We rely on the compiler to common

the two loads of message[i] and to transform the while-loop so there is only one branch, at the bottom of the loop.)

unsigned int crc32(unsigned char *message) {

int i, j;

unsigned int byte, crc, mask;

i = 0;

crc = 0xFFFFFFFF;

while (message[i] != 0) {

byte = message[i]; // Get next byte.

crc = crc ^ byte;

for (j = 7; j >= 0; j--) { // Do eight times.

mask = -(crc & 1);

crc = (crc >> 1) ^ (0xEDB88320 & mask);

}

i = i + 1;

}

return ~crc;

}

FIGURE 14–6. Improved bit-at-a-time CRC-32 algorithm.

Our next version employs table lookup. This is the usual way that CRC-32 is calculated. Although the programs above work one bit at a time, the table lookup method (as usually implemented) works one byte at a time. A table of 256 fullword constants is used.

The inner loop of Figure 14–6 shifts register crc right eight times, while doing an exclusive or operation with a constant when the low-order bit of crc is 1. These steps can be replaced by a single right shift of eight positions, followed

by a single exclusive or with a mask that depends on the pattern of 1-bits in the rightmost eight bits of

the crc register.

It turns out that the calculations for setting up the table are the same as those for computing the CRC of a single byte. The code is shown in Figure 14–7. To keep the program self-contained, it includes steps to set up the table on first use. In practice, these steps would probably be put in a separate function to keep the CRC calculation as simple as possible. Alternatively, the table could be defined by a long sequence of array initialization data. When compiled with GCC to the basic RISC, the function executes 13 instructions per byte of input. This includes two loads and one branch instruction.

Faster versions of these programs can be constructed by standard techniques, but there

is nothing dramatic known to this writer. One can unroll loops and do careful scheduling

of loads that the compiler may not do automatically. One can load the message string

a halfword or a word at a time (with proper attention paid to alignment), to reduce

the number of loads of the message and the number of exclusive or’s of crc with the message (see exercise 1). The table lookup method can process message bytes

two at a time using a table of size 65536 words. This might make the program run faster

or slower, depending on the size of the data cache and the penalty for a miss.

unsigned int crc32(unsigned char *message) {

int i, j;

unsigned int byte, crc, mask;

static unsigned int table[256];

/* Set up the table, if necessary. */

if (table[1] == 0) {

for (byte = 0; byte <= 255; byte++) {

crc = byte;

for (j = 7; j >= 0; j--) { // Do eight times.

mask = -(crc & 1);

crc = (crc >> 1) ^ (0xEDB88320 & mask);

}

table[byte] = crc;

}

}

/* Through with table setup, now calculate the CRC. */

i = 0;

crc = 0xFFFFFFFF;

while ((byte = message[i]) != 0) {

crc = (crc >> 8) ^ table[(crc ^ byte) & 0xFF];

i = i + 1;

}

return ~crc;

}

FIGURE 14–7. Table lookup CRC algorithm.

1. Show that if a generator G contains two or more terms, all single-bit errors are detected.

2. Referring to Figure 14–7, show how to code the main loop so that the message data is loaded one word at a time. For simplicity, assume the message is full-word aligned and an integral number of words in length, before the zero byte that marks the end of the message.