3

“I Just Wanted a World That Looked Like the One I Know”

The Strategically Ambiguous Respectability of a Black Woman Showrunner

Coming in the wake of Oprah Winfrey’s tremendous success, Black women’s visibility on television has undergone a sea change because of television showrunner Shonda Rhimes. Rhimes started her own tidal wave in Hollywood, flowing from the nameless, faceless writer behind the Britney Spears vehicle Crossroads (2002) to a cult figure whose fans and the media alike celebrated for redefining evening melodrama—some might even say television itself—with her hit shows Grey’s Anatomy (2005–present), Private Practice (2007–2013), Scandal (2012–2018), and How to Get Away with Murder (2014–present). Rhimes’ success belied television executives’ oft-whispered reasoning that audiences want to see African American characters only on sitcoms, and it has helped usher in a new era of “diversity” on television. Offscreen, Shonda Rhimes’ leading ladies preside over awards ceremonies, social media, and fashion and gossip rags. Onscreen, her Black women characters are elite, professional women whose work-lives showcase their superstar success and home-lives showcase their tempestuous and deliciously messy interpersonal relationships. They rule our TV fantasy versions of the Washington, D.C. political landscape, tony law schools and law firms, and top-tier surgery suites; they thrive in multiracial cast shows where their race is rarely, if ever, explicitly discussed; they un-self-consciously embrace interracial relationships and interracial friend groups. They are also seldom seen in community with other African American women, appearing to prefer the sisterhood of non-Black women. Race functions as but one of many personality traits in Shondaland, Rhimes’ television production company and the fantasy space it represents.

The auteur of such groundbreaking and cult-like characters quite unusually garners almost as much interest in the press as her stars, or as Oprah Winfrey herself remarked to Rhimes in Winfrey’s first interview of the showrunner in O, The Oprah Magazine, “there are other hit shows, but it’s rare to see so much focus on the writer.” In response, Rhimes demurred: “I didn’t expect this. When the press began asking me for interviews, I freaked out. My instinct is to hide.”1 But her shows’ successes are partially contingent upon her own openness, or appearance thereof, in the press. In this chapter, I trace Rhimes’ performance of postracial resistance through strategic ambiguity in the press during two particular moments, one in the pre-Obama era and at the beginning of her first show—Grey’s Anatomy—when she stuck to a script of colorblindness and garnered entry into an elite Hollywood club, and a second in the #BlackLivesMatter moment and after a string of hits, when she called out racialized sexism and redefined Black female respectability.2

Rhimes’ presentation of self in the media provides a precious archive of one element of strategic ambiguity that I touched upon in this book’s introduction: contemporary Black female respectability politics. Historian Evelyn Brooks Higginbotham coined the phrase “the politics of respectability” to describe a late nineteenth-/early twentieth-century performance by Black church women that rigidly regulated everything from speech, to dress, to religiosity, to truly all means of presenting oneself.3 Black female respectability, as historian Gerald Horne writes, was akin to “‘putting on massa,’ ‘wearing a mask,’ or adopting a personality.”4 A century ago, the women who enacted respectability politics “lifted as they climbed,” to cite the motto of the National Association of Colored Women (NACW).5 Respectability politics, Horne notes, “was seen as necessary to avoid being brutalized or murdered in a society suffused with white supremacy [and] was a trait developed over the centuries by Africans in North America.”6 Today Rhimes showcases herself as, in Lisa B. Thompson’s words, a quintessential “Black lady,”7 whose presentation of self features elements of such respectability.

In the decades that have passed since Higginbotham coined the term in the early 1990s, contemporary notions of African American respectability have changed, largely because of the rise of postracial ideologies that blame the victims of racism instead of racism itself. For example, figures like Bill Cosby communicated respectability in his famous 2004 “Pound Cake” rant at the NAACP’s celebration of the fiftieth anniversary of Brown vs. the Board of Education of Topeka, Kansas.8 Cosby conjured the idea that not only are Black youth today running amuck committing petty crimes, but that when one of those youth gets “shot in the back of the head over [stealing] a piece of pound cake,” we shouldn’t be “outraged.” In other words, disrespectable Black people provoke police violence, and Black respectability, or “pulling your pants up” as Cosby also admonished young African American men, ensures safety and success.

Cosby’s version of respectability—just as sociologist Oscar Lewis put it decades earlier and Assistant Secretary of Labor Daniel Patrick Moynihan codified in his 1965 report The Negro Family: The Case for National Action (known popularly as the Moynihan Report)—was that Black people’s problem was not disenfranchisement through racist institutions and histories; it was the “culture of poverty,” the disrespectable cultural standards that Black people, and particularly pathological Black matriarchs, it maintained.9 Black respectability politics became seen a way for elite African Americans to police and blame poor (or perceived-to-be poor) Blacks, instead of focusing the lens on either interpersonal or institutional racism. In this version, Herman Gray notes the individual focus of respectability politics where “since the social goal of racial uplift initially drove the cultural politics of respectability, the bid on black uplift and social recognition turned on black Americans collectively putting forward an imagined black best self”10 [emphasis in the original]. While Rhimes did not, like Cosby, chide other African Americans for disreputable culture, she does “disavow,” in the words of Higginbotham, “the folk” by featuring elite and professional Black women characters on her cult TV shows who are not in community with other Black women, and largely ignoring institutional and historical racism. In other words, Rhimes and her Black women characters garner success while remaining distanced from communities of Black women; they don’t exactly “lift as they climb.”

Nonetheless, this does not mean that subjects like Rhimes performing Black respectability politics remain silent regarding twenty-first century racism, and especially the racism of microaggressions. Rhimes spoke back through strategic ambiguity, a coded performance that gauges the microaggressions in the air and, if the space feels hostile to explicit resistance, performs colorblindness as a means to an end. In this chapter, I discuss how Rhimes provides another example to the modes of postracial resistance through strategic ambiguity that Michelle Obama successfully (chapter 1) and Oprah Winfrey unsuccessfully (chapter 2) enacted. Like Obama and Winfrey, Rhimes’ version of postracial resistance demonstrates that a performance of strategic ambiguity is strategic in that is a mindful choice; it is ambiguous in that it deploys a primary facet of postrace, not naming racism. It is also ambiguous in that its explicit goal is to simply claim a seat at the table; it is strategic in that inclusion provides an opportunity to repudiate racism. Unlike the direct action of call-outs, walkouts, pickets, or sit-ins, strategic ambiguity is a safe way to respond to racism that comes in a postracial guise because it does not appear to upend the space. Strategic ambiguity is not silence or evasion; it’s a choice to take on a certain amount of risk, to play with fire, to appropriate something that is used against you and make it work for you. Strategic ambiguity is one particular “Black Lady” form of refusal.

However, Rhimes’ performance differs in other key ways from Higginbotham’s description of respectability politics, and not simply because it is a century later. Rhimes is a Hollywood power broker; she garners a power perhaps unimagined by the Black churchwomen of Higginbotham’s study. Our recently past historical moment—the Michelle Obama era—illustrated a discursive meeting of postracial ideologies and #BlackLivesMatter, a time when popular discourse toggled between proclaiming that race and racism were irrelevant in the lives of both people of color and Whites, and acknowledging the daily brutalities disproportionately suffered by Black Americans. Rhimes’ performance of strategic ambiguity channeled a quiet, coded, polite form of Black female resistance that did not shout #BlackLivesMatter slogans or uncomfortably point out discrimination of an interpersonal, structural, or institutional manner.11

As an expression of twenty-first century Black respectability politics, strategic ambiguity functions as a sometimes conflicted, sometimes confounding, and always postracial Black feminist resistance. Strategic ambiguity knits together the contradictions of resistance in the postracial-meets-#BlackLivesMatter moment by featuring two sometimes contradictory elements—colorblindness and race-womanhood (or “wokeness”)—with an exceptionally feminine grace. Reading such resistance is far from a straightforward process. Strategic ambiguity is the tool of Black respectability politics that minoritized subjects use to resist intersectional oppression when, in a postracial moment, those around them script spaces as White-only, ignore oppression, explain it away, or acknowledge it only in a single register (i.e., just racism instead of racialized sexism). Such resistance plays with and reinvents what media sociologist Herman Gray famously named as the three Black televisual discourses: assimilation and invisibility; pluralism and separate-but-equal; and multiculturalism/diversity.12 Postracial resistance incorporates all three discourses into strategic ambiguity by sometimes performing and sometimes refuting them.

Just as all minoritized subjects seeking access to dominant forms of success often play the bait-and-switch game of strategic ambiguity, prominent Black women caught between hypervisibility and invisibility can be spotted rolling out this strategy.13 Where Black men such as Shonda Rhimes’ television star Jesse Williams are given the discursive space to speak truth to power, similarly prominent Black women do not or cannot step into such a space in a similarly forthright manner.14 For example, when presented with a 2016 BET Humanitarian Award for producing work such as the documentary Stay Woke: The Black Lives Matter Movement, Williams gave a rousing speech wherein he memorialized recent Black victims of police brutality, including twelve-year-old Tamir Rice, and unflinchingly told the White audience to “sit down” if they only had “a critique for our resistance.” To the Black audience he proclaimed that “what’s going to happen is we are going to have equal rights and justice in our own country or we will restructure their function and ours.” His comments went viral after this speech, inciting both the adulation of scores of fans across Black Twitter, among other places, and the ire of others who demanded as one online petition did that ABC “fire Jesse Williams from Grey’s Anatomy for racist rant.”15 Rhimes, alongside celebrities such as Michelle Obama, Oprah Winfrey, and Rhimes’ leading lady Kerry Washington, deploys a different form of resistance through strategic ambiguity. Indeed, when Rhimes took to Twitter to defend Williams, she quoted the last line of his speech: “Just because we’re magic doesn’t mean we’re not real.” Rhimes winked to Black Twitter audiences who knew the well-worn trope of the Magic Negro, but she did not directly name or address race or racism.

Like these other Black women celebrities, Rhimes’ self-presentation in the press demonstrates a performance of postracial, carefully-controlled, twenty-first century Black respectability that allows for, in the words of literary scholars Michael Bennett and Vanessa D. Dickerson, a recovery of the Black female body through self-representation.16 Her strategic ambiguity allows a forthright language about race and gender to wax and wane with the space that public discourse allows. Moreover, the press does not describe Rhimes in what production studies scholar John Thornton Caldwell calls the “recognizable iconic themes” of showrunners including “nocturnal and vampire-ish; a bad-boy locked in a bunker surrounded by male teenage memorabilia, rock-and-roll pretense, and an impressively odd intellectual pedigree formed by combinations of high culture, low culture, prestige, and kitsch.”17 Being neither White nor male, Rhimes is allowed none of these quirks, just as she isn’t allowed to, again, in the words of Caldwell, be in this category: “the higher up a male producer is on the food chain, the more slack a company will give him to act out bad-boy and vanguard pretensions as part of the company’s business habit.”18

In this chapter, I trace two Rhimes moments. In the first moment, when Grey’s Anatomy just got its legs and when the press celebrated her and her new show as a success, Rhimes performed a clenched-teeth approach to all aspects of self-disclosure and, in particular, to talking about race and gender. Then, in the second moment, and after a racialized and gendered attack, Rhimes spoke back with an unambiguous critique. She inhabited the space for racialized and gendered self-expression that the ubiquity of #BlackLivesMatter and her Gladiators—her social media fans—opened up. Rhimes’ public statements reveal the magic of postracial resistance and strategic ambiguity, which facilitate her metamorphosis from colorblind to fierce Black feminist subject, all while remaining a pinnacle of feminine, Black respectability. Strategic ambiguity enabled the shift from the pre-Obama era to the #BlackLivesMatter era, where Rhimes’ careful negotiation of the press demonstrated that, in the former moment, to be a respectable African American lady was to not speak frankly about race, while in the latter, respectable Black woman could and must engage in racialized self-expression, and thus redefine the bounds of respectability.

Strategically Ambiguous Rhimes: Colorblindness and the Twenty-First Century Race Woman

In the mid-2000s, colorblindness was an ideology pervading education, the law, and, of course, the media. Despite data demonstrating increasing racialized inequality, affirmative action had been dismantled in states such as California (through Proposition 209 in 1996) and Washington (through Initiative 200 in 1998), and popular discourse in newspaper editorials, educational administration, and courtrooms across the country circulated the fallacy that the twenty-first century United States was now a place of meritocracy.19 The country was settling in to the steady erasure of racial remedies and racial talk, while simultaneously ignoring the steady climb of race-based disparities linked to such erasure. At the same time, the economy boomed, bolstered by predatory home loan practices, which were also racialized.20 Barack Obama was a junior senator from Illinois who wowed the 2004 DNC, but wasn’t yet a postracial icon. Meanwhile, television shows engaged in their own forms of representational racial disproportionality: early 2000s-era scripted network television sparingly featured supporting actors of color in popular shows such as Lost (2004–2010), Heroes (2006–2010), Desperate Housewives (2004–2012), and the CSI franchise (2000–present), while continuing to almost exclusively cast White actors in leading roles.

Rhimes’ new show was greenlit in this moment. Grey’s Anatomy is an evening hospital melodrama set in Seattle, Washington, whose White protagonist, Dr. Meredith Grey, maintains close personal and professional relationships with her many Black and White colleagues, and enjoys, in early seasons, a best-friendship with “her person,” an Asian American woman doctor, and another close friendship with a Latina doctor (Figure 3.1). Grey’s was an instant ratings success across demographic groups, or, as one publication put it rather crassly, it was “doing good business with the young, the old, the whites, the blacks.”21 When Grey’s premiered, the press delightedly and constantly cited Rhimes as the first Black woman showrunner of an hour-long show that lasted past the first season.22 Many articles also scripted Rhimes into her fictional stories, assuming, as media scholar Elana Levine articulated it: “We might account for Grey’s Anatomy’s vision by considering the perspective of the program’s creator and showrunner, Shonda Rhimes … While the idea of a program’s leader is only one of many factors that shape it, we have so few examples in television of an African American woman’s leadership that it is difficult to know what impact Rhimes’s particular perspective may have.”23 Her “particular perspective” bore tremendous weight as critics, fans, and foes alike scrutinized her shows for how they measured up to the litmus test of Black respectability.

Figure 3.1. Diversity anchored by Whiteness. “Season 1 (Grey’s Anatomy).” Fandom. 2005. Viewed October 7, 2017. http://

Rhimes enacted her first performances of Black respectability both in the casting and writing of her television show; she showcased strategic ambiguity in the statements she meted out in her own press coverage. Three of the earliest articles on Rhimes came out in 2005 and 2006 in Ebony magazine, in Written By: The Magazine of the Writers Guild of America, West, and in O: The Oprah Magazine.24 In Ebony, Rhimes said (with my emphasis): “With casting, I don’t care what color they are. If a Black man comes in and he’s great for a part and a White woman comes in and she’s great for the part of his wife, well then, suddenly it’s an interracial couple. And I don’t care. It’s about who’s the most talented getting the parts.” In Written By, Rhimes stated: “‘I basically walked in saying I didn’t write anybody’s race into the [Grey’s Anatomy] script … Let’s make Grey’s look like the world” [my emphasis]. Finally, in O: Oprah Magazine, Rhimes noted: “We read every color actor for every single part. My goal was simply to cast the best actors.” Further, to Winfrey’s inquiry—“Did you set out to elevate the country’s consciousness in terms of racial diversity?”—Rhimes replied: “I just wanted a world that looked like the one I know”25 [my emphasis]. Rhimes’ responses both predicted and warded off journalistic assumptions that a Black woman showrunner was going to be myopically driven by race and race alone. In Rhimes’ narration of her scripting and casting processes, she performed impartiality and an attitude un-swayed by race. Race was ancillary to her read of the world: she “didn’t care.” Providing stories about people of color or opportunities for actors of color was not a carefully scripted decision; it “suddenly” happened, never by design, but rather by happenstance. Rhimes’ world was “the world” (not just “my world”), or everyone’s world, a multiracial one in her scripting. She was simply holding up a mirror to her audience, not cramming diversity down their throats. By featuring “my” and “the” world on her television show, she was following sage, universal advice to all writers: write what you know. Rhimes granted only a handful of interviews in the first season of Grey’s Anatomy and in all of them she stayed on her main talking point: colorblindness.

Through her interviews, Rhimes provided a blueprint of how to garner success as a Black woman in an all-White industry: embrace the language of colorblindness. Rhimes’ careful language was strategically ambiguous in its failure to name race or Blackness; her commitment to her colorblind brand was not just in the text of her shows, but in her own performance to the press. Her language was ambiguous in that it let readers of all races identify themselves both in her narration of herself as a writer and in her shows, and it was strategic in its ability to attract all audiences. Indeed, Rhimes’ statements assured readers that not only is talent not racialized, but neither is access. In other words, slip in diverse actors without fanfare or spotlight, without racially specific storylines, and without specific mention of racialized difference. Never illuminate issues of racism in the ostensibly colorblind televisual landscape, or the allegedly colorblind space of journalism; indeed, never mention racialized difference at all. Journalists gleefully picked up on this trope. For example, in Written By, the author did not introduce race until the fourth page of a six-page article, and then wrote of race as just a personality trait, quipping: “Ah yes, the race thing. Rhimes, as you might have noticed from the photographs, is African American.” Rhimes’ own colorblind discourse encouraged each journalist to discuss race in a cavalier manner because her interviews modeled a strategically ambiguous, postracial ideology.

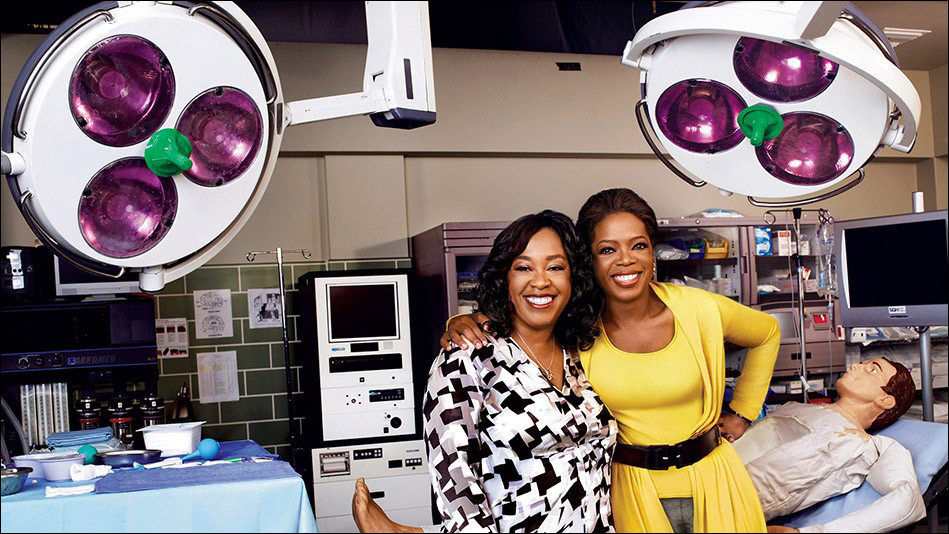

Early articles on Rhimes also discussed her casting process, known as “nontraditional casting,” “cross-racial casting,” “colorblind casting,” and “blindcasting.” These terms essentially mean the same thing: not all-White actors. The three 2005–2006 press quotes showed how, although her audience changed for each publication, her colorblind message did not. While Ebony is by content and design a Black women’s magazine, Rhimes did not target her message to Black women, or spin a story of Black sisterhood. There was no “us” in her narration. The trade magazine Written By received a comparable message from Rhimes. She did not name herself as different from her majority White peers, members of Writers Guild of America (WGA) West, the key audience for this magazine. Rhimes performed similarly in O: Oprah Magazine (Figure 3.2). Rhimes did not identify through a racialized frame with Winfrey, who herself provided an earlier blueprint for strategic ambiguity, as I note in chapter 2. Winfrey primed her multiracial following of women of a certain age to hear Rhimes’ message echoed in Winfrey’s racially transcendent space.26

Figure 3.2. Photographed by Kwaku Alson. “Oprah Talks to Shonda Rhimes.” O: The Oprah Magazine. December 2006. Accessed October 7, 2017. www

While the press coverage of Rhimes posited that cross-racial casting should be seen as racial progress, theater scholar Brandi Catanese argues just the opposite, writing that “cross-racial casting relies upon the assumption that structural inequality is a thing of the past: enduring cultural and racial differences are reduced to surface distractions that a discourse of colorblindness (often connected with notions of transcendence) can remedy.”27 Such “nontraditional casting practices” can be used an excuse that lets White folks off the hook for their own role in perpetuating racism. Catanese explains that cross-racial casting “risk[s] acquiescing to a hierarchy of valuation, suggesting that their only function is to improve people of color.”28 In other words, White people have nothing to do with racism or racial remediation, and their fates aren’t tied to the people of color viewed on our screens. But Whiteness, indeed, is at the heart of such casting practices, as communication scholar Kristen J. Warner notes that color-blind casting, as opposed to consciously casting people of color for racially specific roles, comes from “the fear that white audiences would not tune in,” which “created additional pressure for the showrunners.”29 Furthermore, critic Amy Long asserts, Rhimes certainly must feel such additional pressure, as “Rhimes had to actively point out and work against industrial assumptions that a racially unmarked character calls for a white actor.”30 The industry itself constrained forthright and explicit race conversations.

In these three interviews, Rhimes articulated an ideology of meritocracy: everyone worked equally hard for their roles, and subsequently everyone received equal payoffs. She did not tell the press that she sought to create fantasy spaces, imagining the world she hoped to see. No, she showcased the world she believed she saw and this world “didn’t care” about race. Such a sentiment articulated strategic ambiguity, a 2005-era version of postracial respectability politics for a Black woman public figure. To become successful, Rhimes did not—and perhaps could not—spotlight Black women in a White-dominant space. This was because Rhimes, like Grey’s, as media scholar Timothy Havens notes, “stage[d] the encounter with difference through white main characters.” While Rhimes’ White leading lady can (and, indeed, must) be surrounded by people of color (including, in the eleventh season of the show, a mixed-race African American half-sister), “African American characters … never serve as the main character identification.”31

By being a Black Lady who articulated colorblindness, Rhimes not only avoided saying that “we live in a racist, sexist world,” but she also did not make the (presumed White) audience uncomfortable (and not tune in). In addition to colorblindness, Rhimes’ early press illustrated another aspect of strategic ambiguity: Rhimes scripted herself as both pleasant and an asset to her race. The author in the Ebony article, when describing Rhimes as someone who practiced colorblind casting, also noted that she was “a polite, low-key professional who loves the collaborative process.” She was not rocking the boat. Coded in this statement is that she was a “good girl,” who “got along with others.” Strategic ambiguity in the pre-Obama era by a woman of color meant that she must perform gratitude for simply being included.

However, the press also framed Rhimes as performing another aspect of twenty-first century respectable race woman, one who was—in the words of historian Gerald Horne describing early twentieth-century race women—“imbued with the ideology of racial uplift and determined to make a contribution to her people.”32 While early press coverage showed that Rhimes was conversant in the art and performance of colorblindness, it also narrated Rhimes as a race-conscious, old-school race woman who upheld her people with positive imagery; Ebony described Rhimes as having “a steely determination to avoid stereotypes and deliver positive messages.” Rhimes told the magazine that her “mandate” is: “There will never be any Black drug addicts on our show. There will never be any Black hookers on our show. There will never be Black pimps on our show.” Rhimes explained further: “A lot of shows feel the need and enjoy stereotyping and we’re going the other way. [Perpetuating stereotypes] isn’t something I’m interested in promoting.”33

Figure 3.3. Aldore Collier, “Shonda Rhimes: The Force Behind Grey’s Anatomy.” Ebony. October 2005.

While Rhimes might not have explicitly addressed race in her show, her move to feature images of professional and successful African Americans, and her refusal to represent disreputable characters, spoke to a particular performance of respectability. This aspect of strategic ambiguity, flipping the script instead of addressing the power at play in damaging stereotypes, provided an entry for individual people of color who, by virtue of their “only” status, remained non-threatening, but because of colorblind storylines, had limited power to address issues of racialized inequality head-on.34 Because Rhimes did not explicitly illustrate structural, interpersonal, or historical racism in her press on the show Grey’s Anatomy, the unintended effect was that some audiences saw race as a choice, and that, in Rhimes’ examples, getting addicted to drugs or involved in sex work instead of becoming a doctor came solely from bad choices, not racist or even racialized structures. Rhimes’ interviews with the press from this 2005–6 moment circulated the same colorblind ideologies as her first show, Grey’s Anatomy, and argued that powerful Black women must perform in a colorblind, race-woman, and strategically ambiguous manner in order to become successful in a mainstream space.

Strategic Ambiguity Turns Fierce: Rhimes’ Non-Coded Response to Racialized Sexism

Shonda Rhimes’ second show, Private Practice, premiered just two years into Grey’s Anatomy’s run in the fall of 2007, as then-presidential candidate Barack Obama was emerging as a viable contender for the Democratic nomination. Private Practice was a spin-off program from Grey’s and, like it, featured a White woman surrounded by a multiracial cast, including a Black best friend and Black and Latino love interests. But, for her third show, the cult favorite Scandal, which premiered in the spring of 2012 at the end of President Barack Obama’s first term and well into his re-election campaign, Rhimes diverged from her White-woman-as-leading-lady formula. Internet communities and, in particular, newly formed Black Twitter were giving voice to the movement that would become #BlackLivesMatter, which shone a light on seventeen-year-old Trayvon Martin’s February 26, 2012 murder, and shamed the popular media into covering the tragedy.35 Thus, Scandal premiered in a media landscape very different from that of Rhimes’ first two shows. While discourses of colorblindness still remained present in 2012 discourse, #BlackLivesMatter chipped away at its façade of racial equality.

As Scandal fictionalizes the life of Judy Smith, a real-life African American woman crisis manager or “fixer,” Rhimes cast a Black woman lead, Kerry Washington. Her character Olivia Pope, like Rhimes’ Grey’s and Private Practice protagonists, leads a group of multiracial characters or, rather, in the case of Scandal, a racially mixed group of men, and a number of White women: no other women of color, outside of storylines featuring Olivia Pope’s mother, share the screen with Rhimes’ Black woman lead (Figure 3.4). Rhimes also counter-balanced her leading lady’s Blackness with her love interests: Olivia Pope’s two primary romantic partners were both White men. Shondaland’s crossover approach not only worked onscreen, but also on social media. With Scandal, Rhimes created inventive content; she also, as media scholar Anna Everett notes, innovated “participatory and interactive show experiences and engagements, [that] arguably, have become an unparalleled game-changer in the transformed firmament of network TV production and consumption.”36 Rhimes cultivated a universe of fans on Twitter, a community of Pope & Associates/Shondaland “Gladiators,” many of whom proudly identify as Black women and members of other minoritized groups, and, like Olivia Pope and her team, fight (or at least tweet) for good in a world of evil.

Figure 3.4. Olivia Pope leading her Gladiators in Season 1. Scandal Season 1 Cast Promotional Photo. 2012. Viewed October 7, 2017. http://

Gladiators are, of course, commonly understood as Roman Empire-era male fighters, most, although not all, of whom were of European descent. In classic Hollywood’s version, White male stars such as Kirk Douglas and Lawrence Olivier embodied the personae of the gladiator in Spartacus (1960), while more recently White Australian actor Russell Crowe headlined the blockbuster Gladiator (2000). Flipping a character’s presumed race and gender is a move precisely in line with what Rhimes iterated as her colorblind casting philosophy. However, Shondaland Gladiators did not simply ignore race and gender because they were happy to be included. Instead, they reveled in the racialized and gendered winks of Shondaland and transformed those winks from coded to explicit by, for example, gleefully re-tweeting quick and sly references like Olivia’s “feeling a little [like] Sally Hemings,” the enslaved Black woman who bore Jefferson’s children.37 On social media, self-identified Black women Gladiators proudly identified with Olivia Pope and Shonda Rhimes because, not despite the fact that, they were Black women.

Largely because her Gladiators catapulted Scandal to such fame, Rhimes rode the success of Scandal with the fall of 2014 premiere of How to Get Away with Murder, her second show with a Black woman lead. She ceded showrunner duty for the first time, but the show still bore her stamp. How to Get Away with Murder premiered two years into Barack Obama’s second term as president and two years into the #BlackLivesMatter movement. Just as Rhimes moved from the White-female-led shows Grey’s Anatomy and Private Practice to her Black-female-led shows Scandal and How to Get Away With Murder, press on her show became more focused on race, and she discussed more race questions than in early Grey’s press, albeit still a bit reluctantly and still often in code. For example, in an Elle interview, Rhimes levied a critique of White privilege, stating that “the entire world is skewed from the white male perspective … ‘Normal’ is white male, and I find that to be shocking and ridiculous.”38 In this article, she also unpacked the fallacy of monolithic Blackness, stating that one of her truisms is “My Black Is Not Your Black.” Rhimes went on to explain that limited and limiting representations of African Americans are contingent upon the centering of Whiteness as “What’s terrifying is that, just the same way we’ve all accepted that normal is white, everybody seems to buy into the idea that there’s only one way to be black or one way to be Hispanic. That’s as damaging as anything else.”

While this critique from Rhimes markedly diverged from her previous colorblind language, in Shondaland, the showcasing of diversity of African Americans is really about the showcasing of respectable, upper-class Black folks. Strategic ambiguity, whether showcasing elements of colorblindness or race-consciousness, is on Rhimes’ television shows a performance especially suited to women of color. And, to further historicize her remarks, perhaps Rhimes creates greater discursive space for Blackness with such unequivocal talk; in doing so, she enacts a positionality similar to what literary scholar Sonnet Retman describes African American novelist Sterling Brown enacting in the 1930s and 40s, a positionality that is “not … a representative of the black folk about whom he writes but by still identifying as black, Brown opens up a space for a more complex account of the diversity of black Southern experience, which changes with every locale and generation.”39

Rhimes also pushed back against her earlier staid line of colorblindness in a New York Times Magazine article that praised her for being not only “the most powerful African-American female showrunner in television,” but also “one of the most powerful show runners in the business, full stop.” She responded to the intimation that all characters of color must talk about their race ad nauseaum, noting: “I’m a black woman every day, and I’m not confused about that. I’m not worried about that.” Furthermore, equating race talk with “disempowerment,” she said: “I don’t need to have a discussion with you about how I feel as a black woman, because I don’t feel disempowered as a black woman.”40 While Rhimes’ naming Blackness might be read as refreshing to some, here Rhimes produced an equally flattening stereotype that class-privileged Black women like her only talk about race when commiserating about experiences of racism. She did not note the ways in which racialized stories, jokes, and quips are simply a part of people of color’s everyday communication. Instead, Rhimes stuck with colorblindness, as she did in a Newsweek article where she demurred: “a good story is a good story. It doesn’t matter what the race is, and that’s always been my belief.” She echoed her own earlier colorblind rhetoric in this statement, but also added a race-conscious one: “That said, it was wonderful to have a story [Scandal] based on an African-American woman that called out for an African-American female lead. There didn’t need to be a discussion about it because it was what it was.”41 What she implied—but didn’t explicitly state—was that she had many of these discussions advocating for actors of color in the past. Here Rhimes’ strategic ambiguity shifted with Rhimes modeling how Black respectability can also gesture towards race in a more forthright manner; she also performed as the race woman.

But in the midst of Rhimes’ shift away from colorblindness in her press, she got taken down in the press as a Black woman. When Rhimes started commenting more on race in her shows and—perhaps more importantly—cast two Black women leads in a row, she became the target of a racist attack in the New York Times. Television critic Alessandra Stanley began her article “Wrought in Rhimes’s Image” with the line: “When Shonda Rhimes writes her autobiography, it should be called ‘How to Get Away With Being an Angry Black Woman.’”42 In this article, ostensibly about Rhimes’ new show How to Get Away with Murder (Rhimes executive produces but does not run this show; in fact, the showrunner is a White man), Stanley catalogued the typology of Rhimes’ Black female protagonists through their “volcanic meltdowns,” which she claimed they shared with their creator. Stanley wrote: “Rhimes has embraced the trite but persistent caricature of the Angry Black Woman, recast it in her own image and made it enviable.” Stanley’s careful language, the “recast” and the “enviable,” marked this statement as postracial. By praising Rhimes, in what could be most generously described as a backhanded manner, Stanley’s article wordlessly proclaimed that she couldn’t possibly be racist. However, her suturing of both Rhimes and her Black female protagonists to the Angry Black Woman was not just racialized; it was racist. As chapter 2 illustrates, the Angry Black Woman stereotype operationalized against the foil of the pleasant, innocent White woman who embodied all of the grace and class the Angry Black Woman lacked. The virtuous and blameless White woman might be, in this particular case, Rhimes’ White women fans, the White women actresses ostensibly losing jobs because of Rhimes, or the article’s author herself.

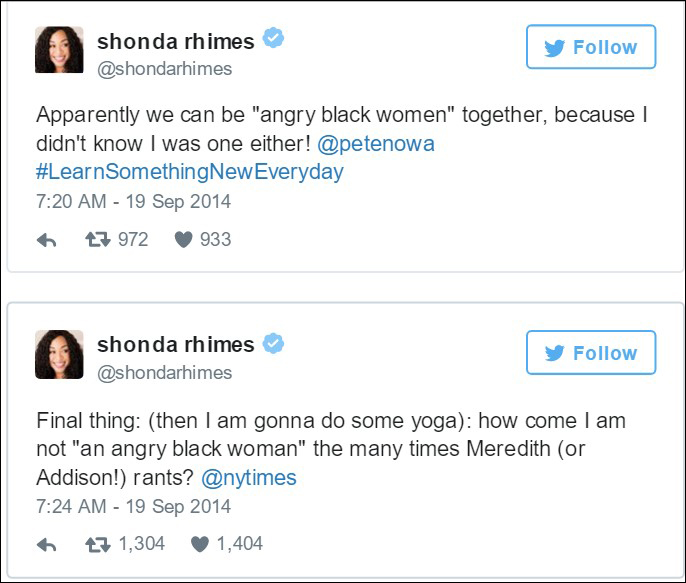

Nevertheless, this story did not end with the triumph of a White woman reporter circulating postracial race/gender stereotypes in the nation’s most venerable newspaper. Rhimes skillfully re-framed the narrative. She responded, quickly followed by her Gladiators, who unsheathed their swords in reaction to this attack and drew their shields close around her. In her response, Rhimes diverged from her then-to-date performance of controlled, respectable, strategic ambiguity. She named the article as racist and sexist, and refuted both through a number of well-stated 140 character responses. On Twitter, noteworthy as home of her Gladiators, she first blasted Stanley on the basis of inaccuracies and racialized sexism, writing (Figure 3.5): “Confused why @nytimes critic doesn’t know identity of CREATOR of show she’s reviewing. @petenowa did u know u were ‘an angry black woman’?” Two minutes later, she again shone a light on the racist, sexist attack, posting: “Apparently we can be ‘angry black women’ together, because I didn’t know I was one either @petenowa #LearnSomethingNewEveryday.”

Her third tweet, three minutes later, also named the stereotype: “Final thing: (then I am gonna do some yoga): how come I am not ‘an angry black woman’ the many times [Grey’s White protagonist] Meredith (or [Private Practice’s White protagonist] Addison!) rants? @nytimes”43 Here Rhimes cast off the cloak of colorblindness by stating, in no uncertain terms, that the media treated White and Black women in wildly divergent, racially stratified ways, and, by the way, racialized sexism was still very much alive. The stars of all four of Rhimes’ shows and her Gladiators exploded with support across Twitter.44 This response highlighted the racism that still exists in even vaunted spheres such as the New York Times, and even against celebrities such as Shonda Rhimes. Apparently mortified by the bad press, the New York Times’ Public Editor Margaret Sullivan herself wrote: “The readers and commentators are correct to protest this story. Intended to be in praise of Ms. Rhimes, it delivered that message in a condescending way that was—at best—astonishingly tone-deaf and out of touch.”45

Figure 3.5. Shonda’s tweets. Screenshot from Shonda Rhimes’ Twitter Account. September 19, 2014. Viewed September 20, 2014. www

While Rhimes’ tweets showcased her Black feminist speaking-Twitter-truth-to-power, after this response, Rhimes didn’t return to the singular colorblindness message of her early press. She moved from colorblind cover to postracial resistance; her strategic ambiguity allowed for this shift. For example, to Entertainment Weekly, Rhimes stated that her parents were the Gladiators in her life, fighting for her “when I encountered something that felt like racism.”46 Here Rhimes named “racism” (almost rhetorically placing scare quotes around the word) but couched it in opinion, “something that felt like,” instead of fact. Rhimes’ critiques of the industry carefully avoided saying “White” or “racism,” instead commenting in a coded manner that “we’ve been watching very homogenous television written by very homogenous people in very homogenous ways.”47 In another example, on NPR, Rhimes showcased her careful language, identifying the fraught-yet-necessary performance of strategic ambiguity: “Nobody wants to talk about it all the time. But if you don’t talk about it, nothing changes, and that’s the trap. You discuss it and spend all your time on it and let it become the only thing about you and let other people see the agenda every time they characterize you: You lose. But you don’t respond, don’t say what you think, don’t share what you know, don’t fire back when you’re minimized or put down or mischaracterized: You lose.”48 In this example, Rhimes powerfully described the ways in which Black women are dismissed and demeaned … and yet she still doesn’t name the “it.” Postracial coding—the silencing of race and racism—is at the heart of strategic ambiguity. And yet, in Rhimes’ press, strategic ambiguity succeeded not at silencing a powerful African American woman and her many Black women fans, but in generating new iterations of coded-and-resistant speech that politely and unobtrusively redefined African American respectability politics in a #BlackLivesMatter era.

Strategic Ambiguity: The Tool of Obfuscation and Exhilaration

Black artists carry a burden of representation. As cultural studies scholar Kobena Mercer put it over twenty years ago, “when black artists become publicly visible only one at a time, their work is burdened with a whole range of extra-artistic concerns precisely because, in their relatively isolated position as one of the few black practitioners in any given field … they are seen as ‘representatives’ who speak on behalf of, and are thus accountable to, their communities.”49 The burden of representation not only unfairly regulates prominent Black artists, but also makes all other Black people invisible: “the visibility of a few token black public figures serves to legitimate, and reproduce, the invisibility, and lack of access to public discourse, of the community as a whole.”50 Such extra weight can mean that even members of a minoritized group can read our representations as declarative statements about our identity group instead of suggestive, playful, measured performances within a particular political economy of race, gender, class, and sexuality. Rhimes’ self-presentation in the press showed that the burden of representation didn’t just weigh heavily in her shows: it weighed heavily on her own articulation of self.

When first becoming a showrunner, Rhimes played the game of coyly responding to the press, whether to O, Written By or Ebony, that she simply wanted to hire the best actors for the part or, as she told Winfrey: “I just wanted a world that looked like the one I know.” For the early part of her career, she succeeded in rolling out some version of these lines; in other words, she was successful at appearing safe, nonthreatening, and accessible—the ultimate crossover. However, her approach changed when she began featuring Black leading ladies, then became the victim of a racist journalistic attack. What does Rhimes’ shift in her messaging to the press—from colorblind subject with a coy “who me?” attitude towards diversity, to a racialized subject with a fairly forward (yet still coded) response to racialized sexism—truly signify? Between the 2005–6 interviews Rhimes granted and her 2014 Twitter responses to the Stanley article, the American political landscape changed. #BlackLivesMatter pointed the spotlight on seemingly state-sanctioned violence against Black people in the United States, and this move opened up a space for all people to cast off the cloak of colorblindness. Prominent Black women in 2014 could—and, indeed, to maintain cred with many fans and social media followers, must—call out racism and sexism. Such call-outs did not just protest physical violence, they also protested representational violence of the form Rhimes experienced in the New York Times. Rhimes’ shift in her performance of respectability politics and strategic ambiguity meant that what constituted respectability politics changed in the #BlackLivesMatter era.

However, while Rhimes’ approaches helped catapult her to the top of her game, not all critics held her strategic ambiguity in high regard. When writing about Grey’s, Amy Long describes Rhimes’ approach—both in the press and in her shows—as one of “obfuscation.” Long also describes the journalists who cover Rhimes as obfuscating structural and institutional racist practices, and blames Shondaland for priming them to not see systemic racism: Grey’s Anatomy’s “characters and storylines consistently fail to attend to the ways in which discourses and institutions structurally and systematically maintain inequalities through the reproduction of powerful gender binaries and racial hierarchies.” At the same time, Long also notes that Rhimes “sometimes succeeds at challenging [racist] discourses.”51 Thus, Long reads such obfuscation into both the show and Rhimes.

Similarly, Kristen J. Warner uses the word “inconsistent” in describing Rhimes’ shows and her self-presentation. On the one hand, she notes, Rhimes “neutralizes race” in order to avoid discussing issues of racial difference or racial inequality.52 Warner lambastes Rhimes for “white-washing” her characters of color and presenting “diversity … [as a] gimmick.”53 But, on the other hand, Warner also notes, her shows aren’t simply hegemonic creations.54 Warner and Long intimate that Rhimes presented her representations of difference as simply enough in and of themselves—and this was a sellout move. I contend that such obfuscation and inconsistency, which also paved a path to Rhimes’ success, were key elements of a postracial resistance that ultimately subbed in new players, while not leveling the playing field. Strategic ambiguity allowed Rhimes to perform contradictory tropes of colorblindness, good girl, race woman, and even fierce Black woman critic while building her empire.

In contrast to Long and Warner’s critiques of Rhimes, media scholar Anna Everett delights in Rhimes and her success, but not because of her strategic ambiguity; she unabashedly and gleefully celebrates her precisely because of her performance of “diversity.” Everett gushes: “Shonda Rhimes [i]s a formidable network TV showrunner and auteur extraordinaire, and … a savvy media mogul who leveraged, especially, Scandal fans’ robust Twitter activism to change the face of American network television in the age of social media, President Obama, and fragmented network TV audience-share.”55 Rhimes brought together her social media savvy with her particular brand of diversity, Everett notes, as “Scandal’s online gladiators have carved out a powerful racially inclusive virtual space for the type of hashtag activism organized around a jubilant multiculturalism.”56 While contemporary audience reception logic states that audiences take their cues from what’s on screen, Everett makes the case that Rhimes and her vast array of cultural products take their cues from the audience, many of whom self-identify as Black women. In Everett’s assessment, not only is Rhimes successful because she mobilized social media in an innovative manner, but also because she did race right in her mobilization. While I wouldn’t go as far as to say that Rhimes does race right, I would say she does race strategically, and one that amounted to success in the Michelle Obama era.

But whether one believes skeptical critics like Long and Warner or celebratory ones like Everett, one thing is clear: Rhimes cracked the code through performing postracial resistance. She created a strategically ambiguous blueprint for twenty-first-century Black women’s success-through-respectability, a colorblindness-meets-#BlackLivesMatter performance. In a Wall Street Journal article, Rhimes drew this blueprint in typically abstruse, non-racialized language: “I always say, if I’m going to go into a difficult conversation, I have to know where I’m going to draw the line before I go into the negotiation.” Then, despite the results of the negotiation, “I always say I’m not surprised, I’m not disappointed, and I didn’t lose—because I held my ground, and in a way, that is a victory.”57 Rhimes’ rules looked like Olivia Pope, her runway strut, achingly beautiful wardrobes, and direct-gazing inquisitions announcing that she will win every negotiation.

Despite being the mistress of the President or the lawyer engaged in a serious breach of ethics (including murder), Shonda Rhimes’ Black women protagonists signify as the pinnacle of Black womanhood. They speak back to the reality star vixens of Love and Hip Hop. They provide counternarratives to, and perhaps are even embarrassed by, the wealthy and drama-loving Real Housewives of Atlanta. They thrive in interracial settings. None of them has a cadre of Black women surrounding them, and therefore no Black women are dragging them down. Each flourishes in being the only, the special, the one who has transcended the imagined boundaries of Black womanhood. This is how Black women enter into and maintain respectability. In contrast, a Black-woman-led show with a Black woman protagonist on Black Entertainment Television, Being Mary Jane, presents an equally flawed and less-than-heroic character, but one whose community of women of color holds up a mirror to her, calls her out, and lifts her up. There is no such mirror to be had in Shonda Rhimes’ creations whether in her TV characters or her creation-of-self in interviews. Nevertheless, in an interactive social media fan space her loyal Gladiators forge one for her week after week.

Both Rhimes’ early success through colorblindness, and the more explicit pushing back after the racist attack are the hallmarks of strategic ambiguity. This dynamic, dialogic form of resistance allows for obfuscation, inconsistency, and jubilant multiculturalism. But its ambiguity not only slides critique past postracial racism, it lets some fans down by merely winking at audiences of color, positing that such an audience is simply pleased to see themselves, as people of color, reflected on their screens. And, for some, it might feel like a relief to experience virtual diversity without racialized strife. The surgeons at Seattle’s Sloan-Grey Memorial Hospital, the doctors at Santa Monica’s Seaside Wellness Center, the fixers at D.C.’s Pope and Associates, and the professor and students at Philadelphia’s Middleton law school suffer through relationship crises while in interracial relationships and yet rarely bring up race. Perhaps to engage in that fantasy is empowering. But, for others, to see visual difference, to feel the weight of racialized discrimination on screen, to understand the living nature of history and yet not discuss historical legacies on racism today feels like a betrayal. Shonda Rhimes’ winking commentary in her press and in her shows isn’t enough to sate every viewer. Postracial resistance and strategic ambiguity might provide a blueprint for Black women’s success, but it’s a success only available to the lucky few, and it’s a success contingent upon the performance of respectability. In the next two chapters, I look into these types of audiences: young women of color who are not satisfied with the winking, nudging, long-game approach of postracial resistance.