CHAPTER 1

The Autodesk Revit World

I'm sure you've seen plenty of presentations on how wonderful and versatile this 3D Autodesk® Revit® revolution is. You may be thinking, “This all seems too complicated for what I do. Why do I need 3D anyway?”

The answer is: You don't need 3D. What do you do to get a job out—that is, after the presentation when you're awarded the project? First, you redraw the plans. Next comes the detail round‐up game we have all come to love: pull the specs together and then plot. This is a simple process that works.

Well, it worked until 3D showed up. Now we have no real clue where things come from, drawings don't look very good, and getting a drawing out the door takes three times as long.

That's the perception, anyway. I've certainly seen all of the above, but I've also seen some incredibly coordinated sets of drawings with almost textbook adherence to standards and graphics. Revit can go both ways—it depends on you to make it go the right way.

One other buzzword I'm sure you've heard about is Building Information Modeling (BIM). Although they say BIM is a process, not an application, I don't fully buy into that position. Right now, you're on the first page of BIM. BIM starts with Revit. If you understand Revit, you'll understand Building Information Modeling.

This chapter will dive into the Revit graphical user interface (GUI) and tackle the three topics that make Revit … well, Revit:

- The Revit interface

- The Project Browser

- File types and families

The Revit Interface

Toto, we aren't in CAD anymore!

If you just bought this book, then welcome to the Revit world. In Revit, the vast majority of the processes you encounter are in a flat 2D platform. Instead of drafting, you're placing components into a model. Yes, these components have a so‐called third dimension to them, but a logical methodology drives the process. If you need to see the model in 3D, it's simply a click away. That being said, remember this: There is a big difference between 3D drafting and modeling.

With that preamble behind us, let's get on with it.

First of all, Revit has no command prompt and no crosshairs. Stop! Don't go away just yet. You'll get used to it, I promise. Unlike most CAD applications, Revit is heavily pared down, so to speak. It's this way for a reason. Revit was designed for architects and engineers. You don't need every command that an individual designing a car would need. An electrical engineer wouldn't need the functionality that an architect would require. In Revit, however, the functionality I just mentioned is available, but it's tucked away so as not to interfere with your architectural pursuits.

You'll find that, as you get comfortable with Revit, there are many, many choices and options behind each command.

Let's get started:

- To open Revit, click the icon on your desktop (see Figure 1.1).

FIGURE 1.1 You can launch Revit from the desktop icon.

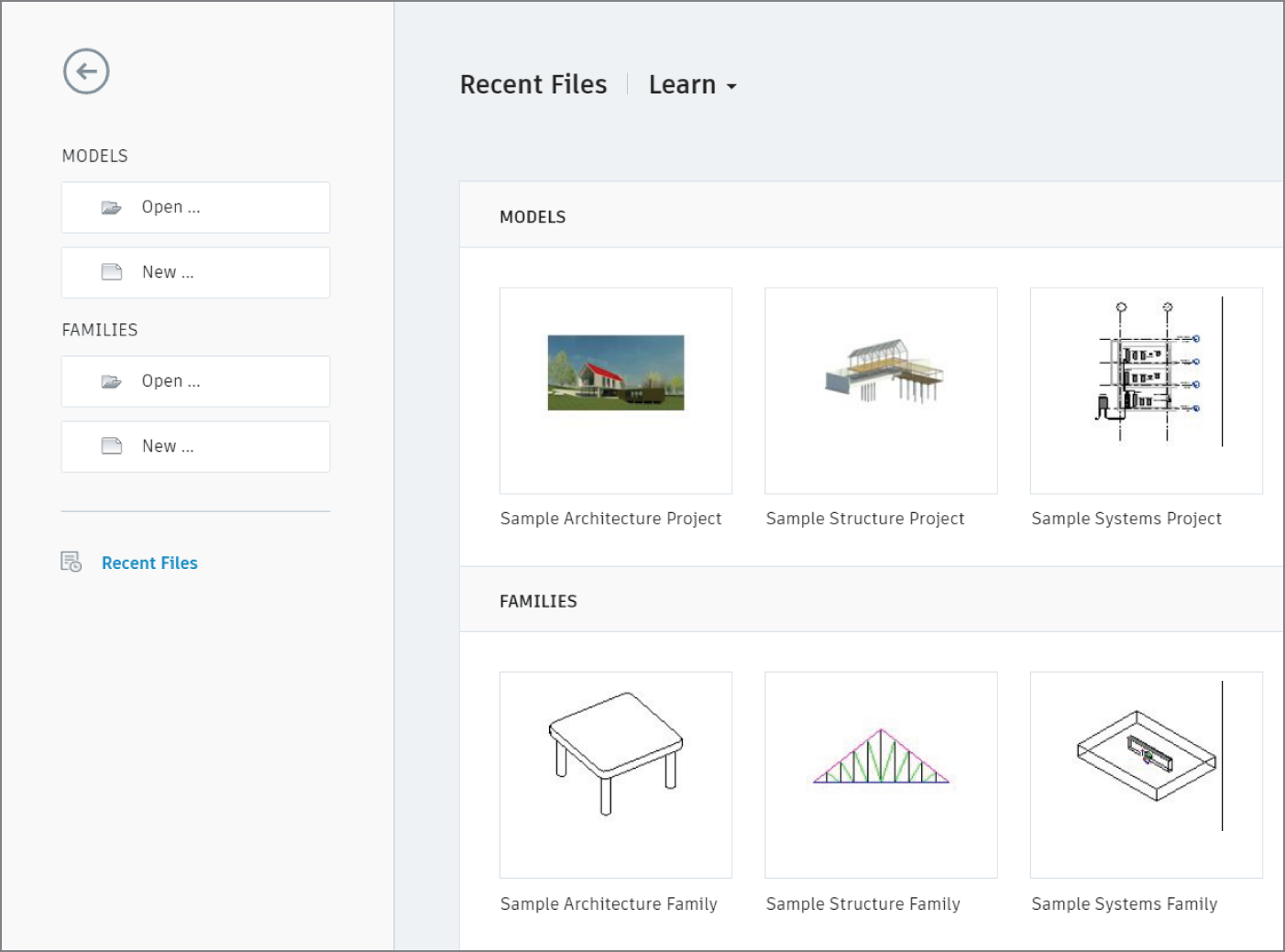

- After you start Revit, you'll see the Recent Files window, as shown in Figure 1.2. The top row lists any projects on which you've been working; the bottom row lists any families with which you've been working. At the top of the dialog is the Learn pulldown. This will give you access to the Autodesk Help website.

FIGURE 1.2 The Recent Files window lists any recent projects or families on which you've worked.

- To the left of the dialog is the Models area. Click the Open… link.

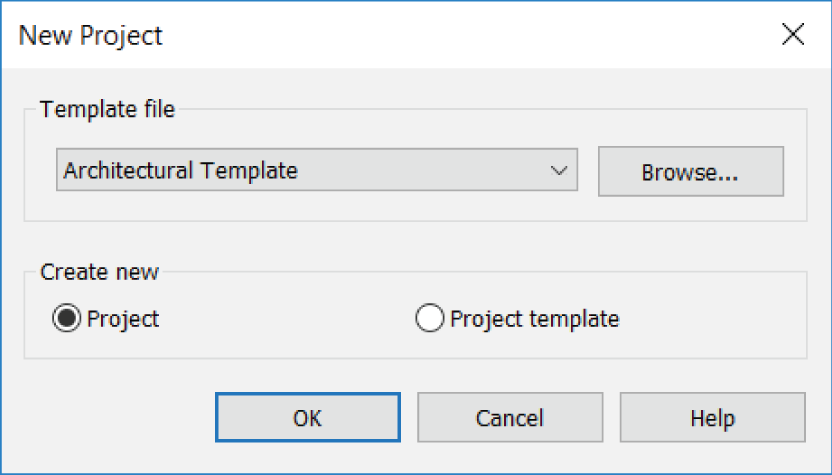

- The New Project dialog shown in Figure 1.3 opens. Click the Template File drop‐down menu, and select Architectural Template. If you're a metric user, click the Browse button. This will open Windows Explorer. Go up one level, and choose the

US Metricfolder. Select the file calledDefaultMetric.rte. If you cannot find this file, please go to the book's accompanying website (www.wiley.com/go/revit2020ner) and download all files pertaining to the entire book—especially the files for Chapter 1.

Now that the task of physically opening the application is out of the way, we can delve into Revit. Revit has a certain feel that Autodesk® AutoCAD® converts, or MicroStation converts, will need to grasp. At first, if you're already a CAD user, you'll notice many differences between Revit and CAD. Some of these differences may be off‐putting, whereas others will make you say, “I wish CAD did that.” Either way, you'll have to adjust to a new workflow.

FIGURE 1.3 The New Project dialog allows you to start a new project using a preexisting template file, or you can create a new template file.

The Revit Workflow

This new workflow may be easy for some to adopt, whereas others will find it excruciatingly foreign. (To be honest, I found the latter to be the case at first.) Either way, it's a simple concept. You just need to slow down a bit from your CAD habits. If you're new to the entire modeling/drafting notion, and you feel you're going too slowly, don't worry. You do a lot with each click of the mouse.

Executing a command in Revit is a three‐step process:

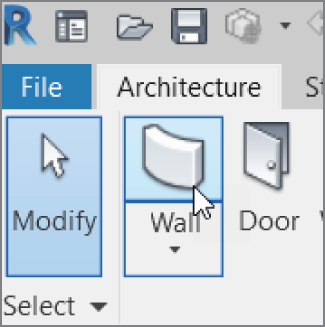

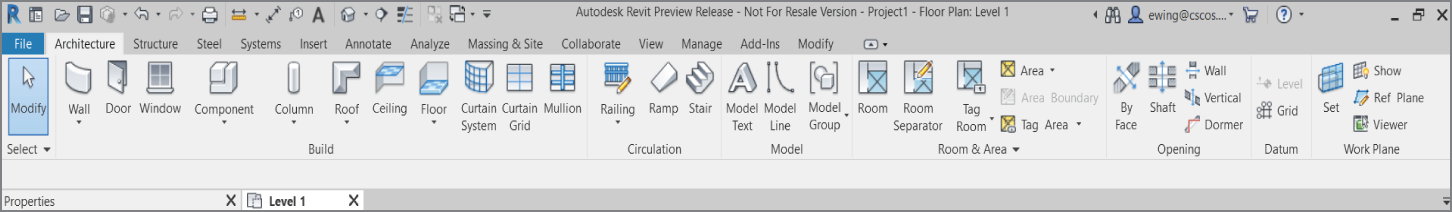

- At the top of the Revit window is the Ribbon. A series of tabs is built into the Ribbon. Each tab contains a panel. This Ribbon will be your Revit launchpad! Speaking of launchpads, click the Wall button on the Architecture tab, as shown in Figure 1.4.

FIGURE 1.4 The Ribbon is the backbone of Revit.

- After you click the Wall button, notice that Revit adds a tab to the Ribbon with additional choices specific to the command you're running, as shown in Figure 1.5. You may also notice that Revit places an additional Options bar below the Ribbon for even more choices.

FIGURE 1.5 The Options bar allows you to have additional choices for the current command.

- After you make your choices from the Ribbon and the Options bar, you can place the object into the view window. This is the large drawing area that takes up two‐thirds of the Revit interface. To place the wall, simply pick a point in the window and move your pointer in the direction that you want the wall to travel. The wall starts to form. Once you see that, you can press the Esc key to exit the command. (I just wanted to illustrate the behavior of Revit during a typical command.)

Using Revit isn't always as easy as this, but just keep this basic three‐step process in mind and you'll be okay:

- Start a command.

- Choose an option from the temporary tab or the Options bar that appears.

- Place the item in the view window.

Thus, on the surface Revit appears to offer a fraction of the choices and functionality that are offered by AutoCAD (or any drafting program, for that matter). This is true in a way. Revit does offer fewer choices to start a command, but the choices that Revit does offer are much more robust and powerful.

Revit keeps its functionality focused on designing and constructing buildings. Revit gets its robust performance from the dynamic capabilities of the application during the placement of the items and the functionality of the objects after you place them in the model. You know what they say: never judge a book by its cover—unless, of course, it's the book you're reading right now.

Let's keep going with the main focus of the Revit interface: the Ribbon. You'll be leaning on the Ribbon extensively in Revit.

Using the Ribbon

You'll use the Ribbon for the majority of the commands you execute in Revit. As you can see, you have little choice but to do so. However, this is good because it narrows your attention to what is right in front of you.

When you click an icon on the Ribbon, Revit will react to that icon with a new tab, giving you the specific additional commands and options you need. Revit also keeps the existing tabs that can help you in the current command, as shown in Figure 1.6. Again, the focus is on keeping your eyes in one place.

FIGURE 1.6 The Ribbon breakdown showing the panels

In this book, I'll throw quite a few new terms at you, but you'll get familiar with them quickly. We just discussed the Ribbon, but mostly you'll be directed to choose a tab in the Ribbon and to find a panel on that tab.

To keep the example familiar, when you select the Wall button, your instructions will read: “On the Build panel of the Architecture tab, click the Wall button.”

Now that you can see how the Ribbon and the tabs flow together, let's look at another feature in the Ribbon panels that allows you to reach beyond the immediate Revit interface.

The Properties Interface

When you click the Wall button, a new set of commands appears on the Ribbon. This new set of commands combines the basic Modify commands with a tab specific to your immediate process. In this case, that process is adding a wall.

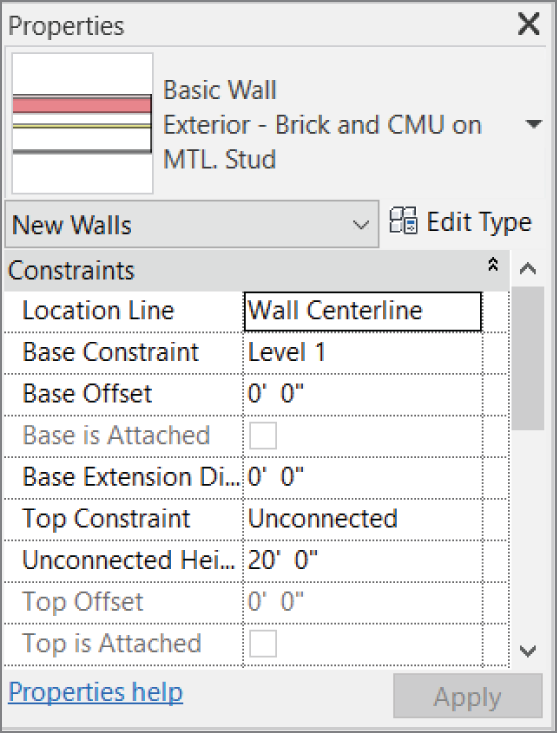

You'll also notice that the Properties dialog near the left of the screen changes, as shown in Figure 1.7. The Properties dialog shows a picture of the wall you're about to place. If you click this picture, Revit displays all the walls that are available in the model. This display is called the Type Selector drop‐down (see Figure 1.8).

FIGURE 1.7 Click the Properties button to display the Properties dialog. Typically, the dialog is shown by default.

The objective of the next exercise is to start placing walls into the model:

- Close Revit by clicking the close button in the upper‐right corner.

- Reopen Revit, and start a new project (Metric or Imperial).

- On the Architecture tab, click the Wall button.

- In the Properties dialog, select Exterior ‐ Brick And CMU On MTL. Stud from the Type Selector. (Metric users, select Basic Wall ‐ Exterior Brick On Mtl. Stud. This will look somewhat different throughout the book, but you get a break. It is slightly easier to work with than the Imperial wall type.)

Element Properties

There are two different sets of properties in Revit: instance properties and type properties. Instance properties are available immediately in the Properties dialog when you place or select an item. If you make a change to an element property, the only items that are affected in the model are the items you've selected.

FIGURE 1.8 The Properties dialog gives you access to many variables associated with the item you're adding to the model.

The Properties Dialog

As just mentioned, the Properties dialog displays the instance properties of the item you've selected. If no item is selected, this dialog displays the properties of the current view in which you happen to be.

You also have the ability to combine the Properties dialog with the adjacent dialog, which is called the Project Browser (we'll examine the Project Browser shortly). Simply click the top of the Properties dialog, as shown in Figure 1.9, and drag it onto the Project Browser. Once you do this, you'll see a tab that contains the properties and a tab that contains the Project Browser (also shown in Figure 1.9).

Let's take a closer look at the two categories of element properties in Revit.

Instance Properties

The items that you can edit immediately are called parameters or instance properties. These parameters change only the object being added to the model at this time. Also, if you select an item that has already been placed in the model, the parameters you see immediately in the Instance Properties dialog change only that item you've selected. This makes sense—not all items are built equally in the real world. Figure 1.10 illustrates the instance properties of a typical wall.

FIGURE 1.9 Dragging the Properties dialog onto the Project Browser

Type Properties

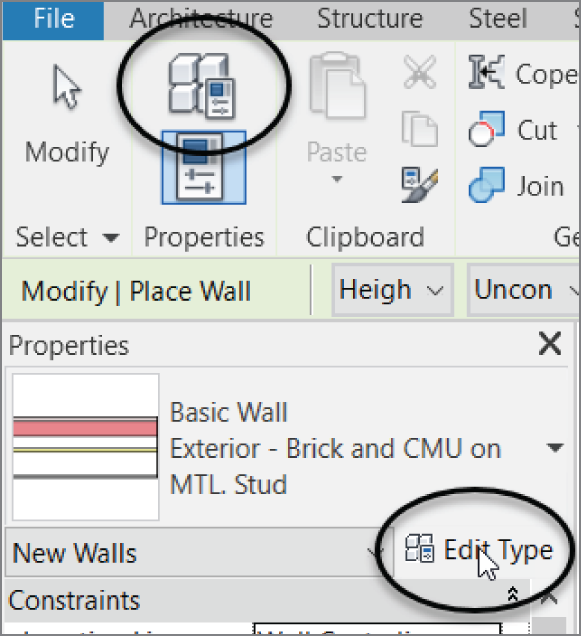

Type properties (see Figure 1.11), when edited, alter every item of that type in the entire model. To access the type properties, click the Edit Type button in the Properties dialog, as Figure 1.12 shows.

At this point, you have two choices. You can make a new wall type (leaving this specific wall unmodified) by clicking the Duplicate button at the upper right of the dialog, or you can start editing the wall's type properties, as shown in Figure 1.13.

Now that you've gained experience with the Type Properties dialog, it's time to go back and study the Options bar as it pertains to placing a wall:

- Because you're only exploring the element properties, click the Cancel button to return to the model.

FIGURE 1.10 The instance properties change only the currently placed item or the currently selected item.

FIGURE 1.11 The type properties, when modified, alter every occurrence of this specific wall in the entire model.

FIGURE 1.12 The Edit Type button allows you to access the type properties.

FIGURE 1.13 The type properties modify the wall system's global settings. Click the Preview button at the bottom of the dialog to see the image that is displayed.

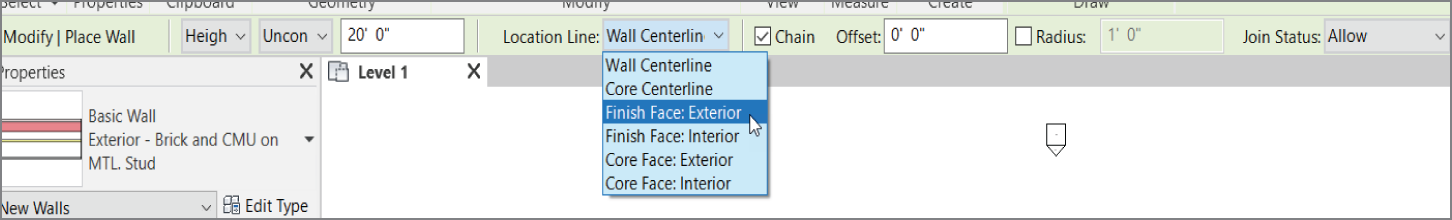

- Back in the Options bar, find the Location Line menu. Through this menu, you can set the wall justification. Select Finish Face: Exterior (see Figure 1.14).

FIGURE 1.14 By selecting Finish Face: Exterior, you know the wall will be dimensioned from the outside finish.

- On the Options bar, be sure the Chain check box is selected, as Figure 1.14 shows. This will allow you to draw the walls continuously.

- The Draw panel has a series of sketch options. Because this specific wall is straight, make sure the Line button is selected, as shown in Figure 1.15.

FIGURE 1.15 You can draw any shape you need.

Get used to studying the Ribbon and the Options bar—they will be your crutch as you start using Revit! Of course, at some point you need to begin placing items physically into the model. This is where the view window comes into play.

The View Window

To put it simply, the big white area where the objects go is the view window. As a result of your actions, this area will become populated with your model. Notice that the background is white—this is because the sheets you plot on are white. In Revit, what you see is what you get … literally. Line weights in Revit are driven by the object, not by the layer. In Revit, you aren't counting on color #5, which is blue, for example, to be a specific line width when you plot. You can immediately see the thickness that all your lines will be before you plot (see Figure 1.16). What a novel idea.

FIGURE 1.16 The view window collects the results of your actions.

To continue placing some walls in the model, keep going with the exercise. (If you haven't been following along, you can start by clicking the Wall button on the Architecture tab. In the Properties dialog box, select Exterior ‐ Brick And CMU On MTL. Stud [or Basic Wall ‐ Exterior Brick On Mtl. Stud for metric users]. Make sure the wall is justified to the finish face exterior.) You may now proceed:

- With the Wall command still running and the correct wall type selected, position your cursor in a location similar to the illustration in Figure 1.17. Pick a point in the view window.

- With the first point picked, move your cursor to the left. Notice that two things happen: the wall seems to snap in a horizontal plane, and a blue dashed line locks the horizontal position. In Revit, there is no Ortho. Revit aligns the typical compass increments to 0°, 90°, 180°, 270°, and 45°.

- Also notice the blue dimension extending from the first point to the last point. Although dimensions can't be typed over, this type of dimension is a temporary dimension for you to use as you place items. Type 100′ (30000 mm), and press the Enter key. Notice that you didn't need to type the foot mark (′) or mm. Revit thinks in terms of feet or millimeters. The wall is now 100′ (30000 mm) long (see Figure 1.17).

FIGURE 1.17 The procedure for drawing a wall in Revit

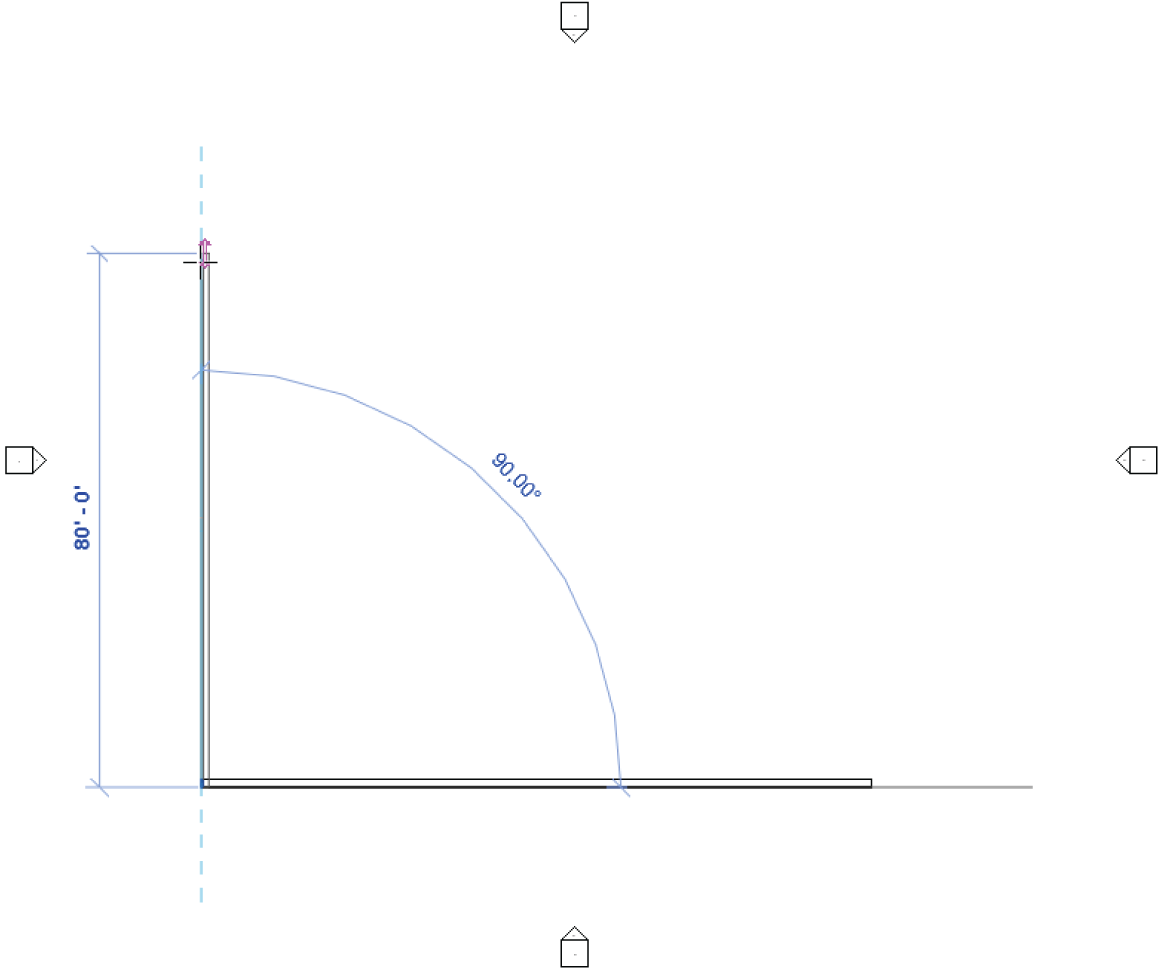

- With the Wall command still running, move your cursor straight up from the endpoint of your 100′‐long wall. Look at Figure 1.18.

FIGURE 1.18 How Revit works is evident in this procedure.

- Type 80′ (24000 mm), and press Enter. You now have two walls.

- Move your cursor to the right until you run into another blue alignment line. Notice that your temporary dimension says 100′–0″ (30000.0). Revit understands symmetry. After you see this alignment line, and the temporary dimension says 100′–0″ (30000.0), pick this point.

- Move your cursor straight down, type 16′ (4800 mm), and press Enter.

- Move your cursor to the right, type 16′ (4800 mm), and press Enter.

- Press the Esc key twice.

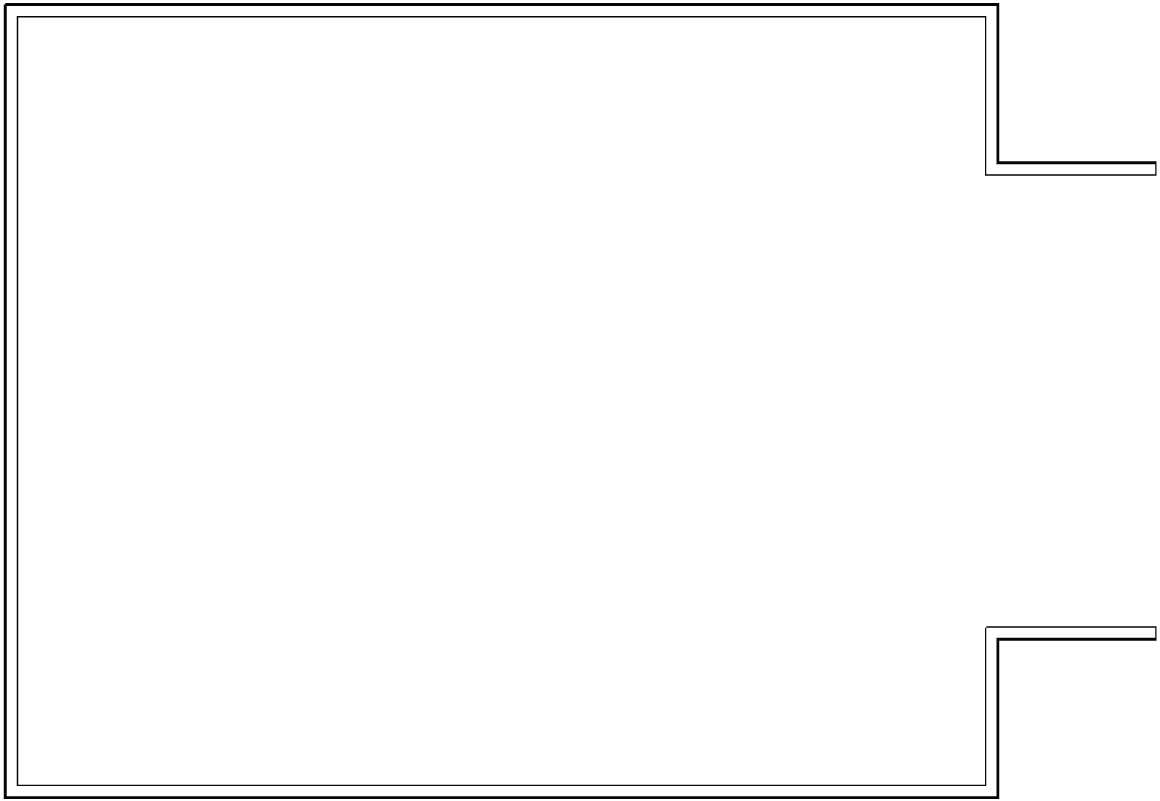

Do your walls look like Figure 1.19? If not, try it again. You need to be comfortable with this procedure (as much as possible).

FIGURE 1.19 Working with Revit starts with the ability to work with the view window and learn the quirks and feel of the interface.

To get used to the Revit flow, always remember these three steps:

- Start a command.

- Focus on your options.

- Move to the view window, and add the elements to the model.

If you start a command and then focus immediately on the view, you'll be sitting there wondering what to do next. Don't forget to check your Options bar and the appropriate Ribbon tab.

Let's keep going and close this building by using a few familiar commands. If you've never drafted on a computer before, don't worry. These commands are simple. The easiest but most important topic is how to select an object.

Object Selection

Revit has a few similarities to AutoCAD and MicroStation. One of those similarities is the ability to perform simple object selection and to execute common modify commands. For this example, you'll mirror the two 16′–0″ (4800 mm) L‐shaped walls to the bottom of the building:

- Type ZA (zoom all).

- Near the two 16′–0″ (4800 mm) L‐shaped walls, pick (left‐click) and hold down the left mouse button when the cursor is at a point to the right of the walls but above the long, 100′–0″ (30000 mm) horizontal wall.

- You see a window start to form. Run that selection window down and to the left past the two walls. After you highlight the walls, as shown in Figure 1.20, let go of the mouse button, and you've selected the walls.

There are two ways to select an object: by using a crossing window or by using a box. Each approach plays an important role in how you select items in a model.

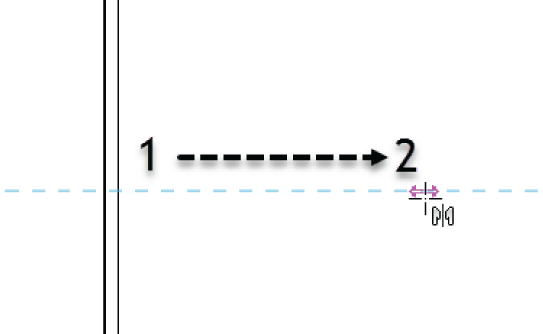

Crossing Windows

A crossing window is an object‐selection method in which you select objects by placing a window that crosses through the objects. A crossing window always starts from the right and ends to the left. When you place a crossing window, it's represented by a dashed‐line composition (as you saw in Figure 1.20).

FIGURE 1.20 Using a crossing window to select two walls

Boxes

With a box object‐selection method, you select only items that are 100 percent inside the window you place. This method is useful when you want to select specific items while passing through larger objects that you may not want in the selection set. A box always starts from the left and works to the right. The line type for a selection window is a continuous line (see Figure 1.21).

Now that you have experience selecting items, you can execute some basic modify commands. Let's begin with mirroring, one of the most popular modify commands.

Modifying and Mirroring

Revit allows you either to select the item first and then execute the command or to start the command and then select the objects to be modified. This is true for most action items and is certainly true for every command on the Modify toolbar. Try it:

- Make sure only the two 16′–0″ (4800 mm) walls are selected.

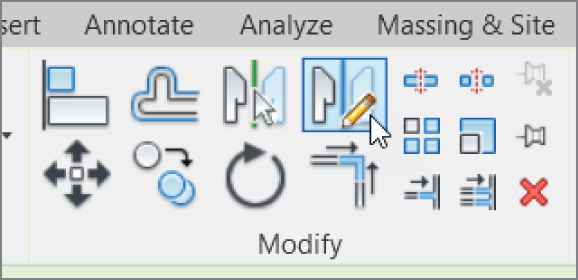

- When the walls are selected, the Modify | Walls tab appears. On the Modify panel, click the Mirror – Draw Axis button, as shown in Figure 1.22.

FIGURE 1.21 To select only objects that are surrounded by the window, use a box. This will leave out any item that may be partially within the box.

FIGURE 1.22 The Ribbon adds the appropriate commands.

- Your cursor changes to a crosshair with the mirror icon, illustrating that you're ready to draw a mirror plane.

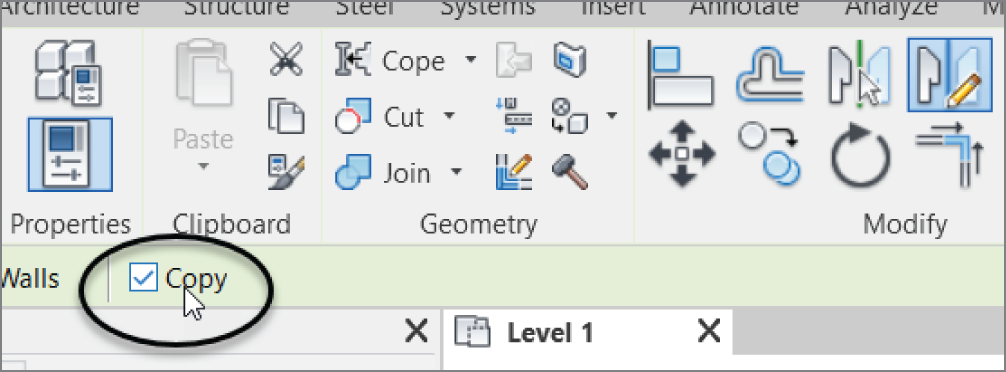

- Make sure the Copy check box is selected (see Figure 1.23).

FIGURE 1.23 There are options you must choose for every command in Revit.

- Hover your cursor over the inside face of the 80′–0″ (24000 mm) vertical wall until you reach the midpoint. Revit displays a triangular icon, indicating that you've found the midpoint of the wall (see Figure 1.24).

FIGURE 1.24 Revit has snaps similar to most CAD applications. In Revit, you'll get snaps only if you choose the Draw icon from the Options bar during a command.

- When the triangular midpoint snap appears, pick this point. After you pick the point where the triangle appears, you can move your cursor directly to the right of the wall. An alignment line appears, as shown in Figure 1.25. When it does, you can pick another point along the path. When you pick the second point, the walls are mirrored and joined with the south wall (see Figure 1.26).

FIGURE 1.25 Mirroring these walls involves (1) picking the midpoint of the vertical wall and (2) picking a horizontal point along the plane.

FIGURE 1.26 Your building should look like this illustration.

Now that you have some experience mirroring items, it's time to start adding components to your model by using the items that you placed earlier. If you're having trouble following the process, retry these first few procedures. Rome wasn't built in a day. (Well, perhaps if they'd had Revit, it would have sped things up!) You want your first few walls to look like Figure 1.26.

Building on Existing Geometry

You have some geometry with which to work, and you have some objects placed in your model. Now Revit starts to come alive. The benefits of using Building Information Modeling will become apparent quickly, as explained later in this chapter. For example, because Revit knows that walls are walls, you can add identical geometry to the model by simply selecting an item and telling Revit to create a similar item.

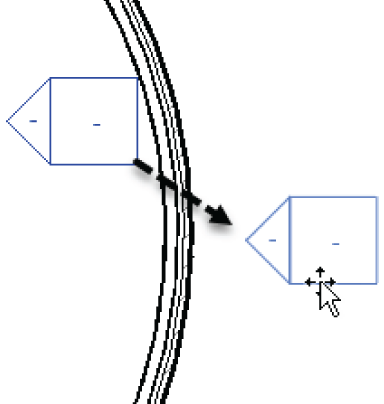

Suppose you want a radial wall of the same exact type as the other walls in the model. Perform the following steps:

- Type ZA to zoom the entire screen.

- Press the Esc key.

- Select one of the walls in the model—it doesn't matter which one.

- Right‐click the wall.

- Select Create Similar, as shown in Figure 1.27.

FIGURE 1.27 You can select any item in Revit and create a similar object by right‐clicking and selecting Create Similar.

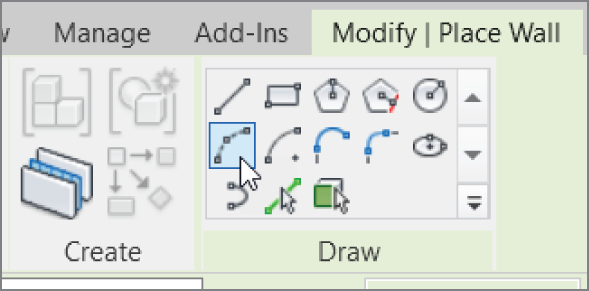

- On the Modify | Place Wall tab, click the Start‐End‐Radius Arc button, as shown in Figure 1.28.

FIGURE 1.28 Just because you started the command from the view window doesn't mean you can ignore your options.

- Again with the options? Yes. Make sure Location Line is set to Finish Face: Exterior (it should be so already).

- With the wheel button on your mouse, zoom into the upper corner of the building and select the top endpoint of the wall, as shown in Figure 1.29. The point you're picking is the corner of the heavy lines. The topmost, thinner line represents a concrete belt course below. If you're having trouble picking the correct point, don't be afraid to zoom into the area by scrolling the mouse wheel. (Metric users do not have the concrete belt. Just pick the outside heavy line representing the brick face.)

- Select the opposite, outside corner of the bottom wall. Again, to be more accurate you'll probably have to zoom into each point as you're making your picks.

FIGURE 1.29 Select the top corner of the wall to start your new radial wall.

- Move your cursor to the right until you see the curved wall pause. You'll see an alignment line and possibly a tangent snap icon appear as well. Revit understands that you may want an arc tangent on the two lines you've already placed in your model.

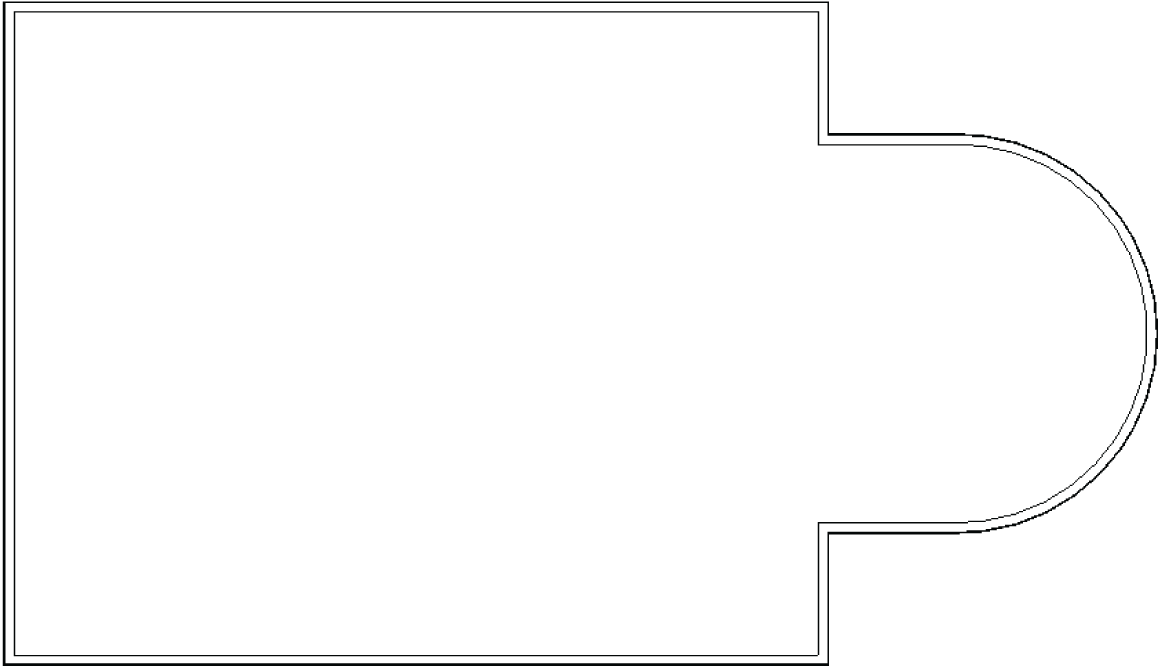

- When you see the tangent snap icon, choose the third point. Your walls should look like Figure 1.30.

FIGURE 1.30 The completed exterior walls should look like this illustration.

Just because you've placed a wall in the model doesn't mean the wall looks the way you would like it to appear. In Revit, you can do a lot with view control and how objects are displayed.

View Control and Object Display

Although the earlier procedures are a nice way to add walls to a drawing, they don't reflect the detail you'll need to produce construction documents. The great thing about Revit, though, is that you've already done everything you need to do. You can now tell Revit to display the graphics the way you want to see them.

The View Control Bar

At the bottom of the view window, you'll see a skinny toolbar (as shown in Figure 1.31). This is the View Control bar.

FIGURE 1.31 The View Control bar controls the graphical view of your model.

It contains the functions outlined in the following list:

Scale The first item on the View Control bar is the Scale function. It gets small mention here, but it's a huge deal. In Revit, you change the scale of a view by selecting this menu. Change the scale here, and Revit will scale annotations and symbols accordingly (see Figure 1.32).

FIGURE 1.32 The Scale menu allows you to change the scale of your view.

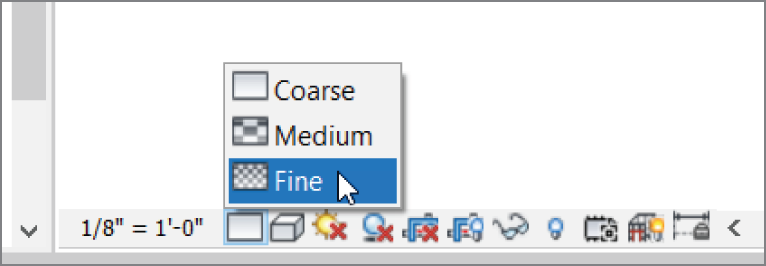

Detail Level Detail Level allows you to view your model at different qualities. You have three levels to choose from: Coarse, Medium, and Fine (see Figure 1.33).

FIGURE 1.33 The Detail Level control allows you to set different view levels for the current view.

If you want more graphical information with this view, select Fine. To see how the view is adjusted using this control, follow these steps:

- Click the Detail Level icon, and choose Fine.

- Zoom in on a wall corner. Notice that the wall components are now showing in the view.

There are other items on the View Control bar, but we'll discuss them when they become applicable to the exercises.

The View Tab

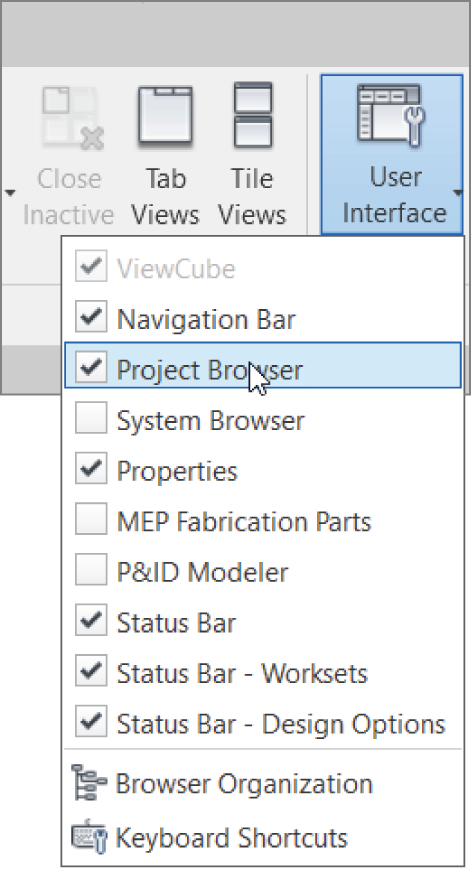

Because Revit is one big happy model, you'll quickly find that simply viewing the model is quite important. In Revit, you can take advantage of some functionality in the Navigation bar. To activate the Navigation bar, first go to the View tab and click the User Interface button. Then go to the default 3D view, and make sure the Navigation bar is activated, as shown in Figure 1.34.

One item we need to look at on the Navigation bar is the steering wheel.

The Steering Wheel

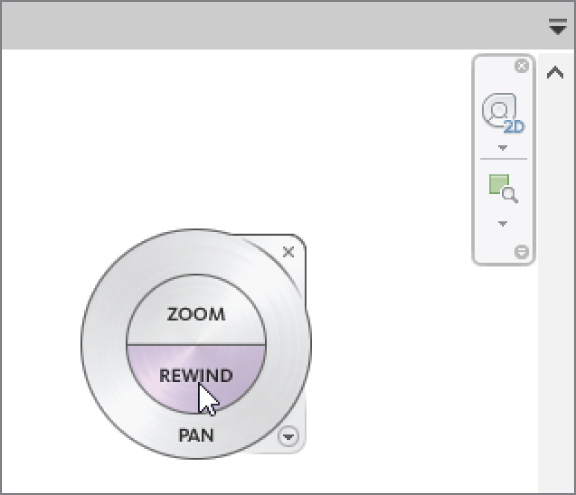

The steering wheel allows you to zoom, rewind, and pan. When you click the steering wheel icon, a larger control panel appears in the view window. To choose one of the options, you simply pick (left‐click) one of the options and hold down the mouse button as you execute the maneuver.

To use the steering wheel, follow along:

- Go back to Floor Plan Level 1, and pick the steering wheel icon from the Navigation bar.

- When the steering wheel is in the view window (as shown in Figure 1.35), left‐click and hold Zoom. You can now zoom in and out.

FIGURE 1.34 The View tab allows you to turn on and off the Navigation bar.

FIGURE 1.35 You can use the steering wheel to navigate through a view.

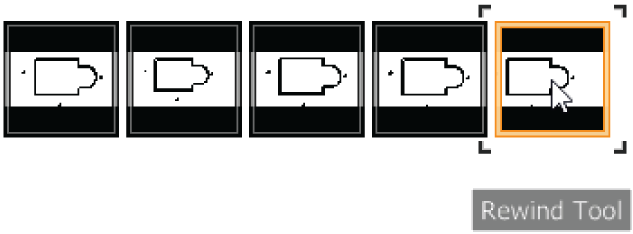

- Click and hold Rewind in the steering wheel. You can now find an older view, as shown in Figure 1.36.

FIGURE 1.36 Because Revit doesn't include zoom commands in the Undo function, you can rewind to find previous views.

- Do the same for Pan, which is found on the outer ring of the steering wheel. After you click and hold Pan, you can navigate to other parts of the model.

Although you can do all this with your wheel button, some users still prefer the icon method of panning and zooming. For those of you who prefer the icons, you'll want to use the icons for the traditional zooms as well.

When you're finished using the steering wheel, press Shift+W or right‐click and choose Close Wheel.

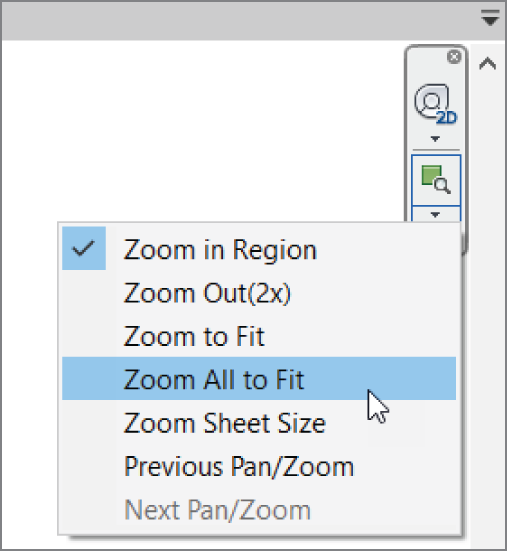

Traditional Zooms

The next items on the Navigation bar are the good‐old zoom controls. The abilities to zoom in, zoom out, and pan are all included in this function, as shown in Figure 1.37.

FIGURE 1.37 The standard zoom commands

Of course, if you have a mouse with a wheel, you can zoom and pan by either holding down the wheel to pan or wheeling the button to scroll in and out.

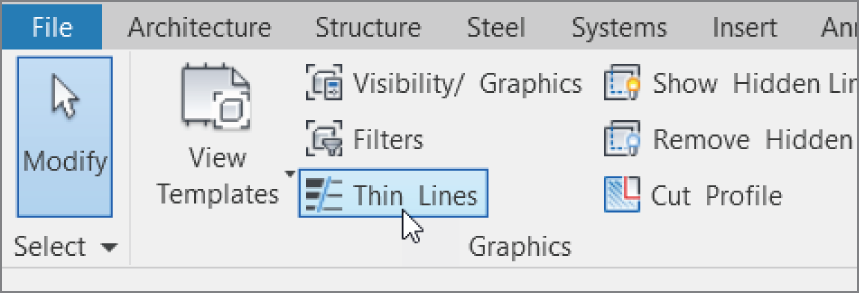

Thin Lines

Back on the View tab, you'll see an icon called Thin Lines, as shown in Figure 1.38. Let's talk about what this icon does.

FIGURE 1.38 Clicking the Thin Lines icon lets you operate on the finer items in a model.

In Revit, there are no layers. Line weights are controlled by the actual objects they represent. In the view window, you see these line weights. As mentioned before, what you see is what you get.

Sometimes, however, these line weights may be too thick for smaller‐scale views. By clicking the Thin Lines icon, as shown in Figure 1.38, you can force the view to display only the thinnest lines possible and still see the objects.

To practice using the Thin Lines function, follow along:

- Pick the Thin Lines icon.

- Zoom in on the upper‐right corner of the building.

- Pick the Thin Lines icon again. This toggles the mode back and forth.

- Notice that the lines are very heavy.

The line weight should concern you. As mentioned earlier, there are no layers in Revit. This subject will be covered throughout this book.

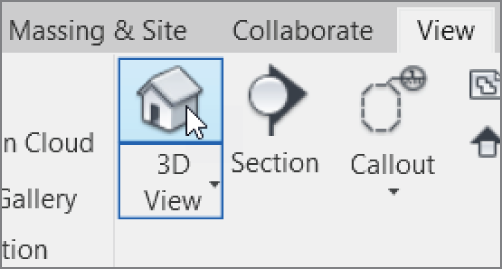

3D View

The 3D View icon brings us to a new conversation. Complete the following steps, which will move us into the discussion of how a Revit model comes together:

- Click the 3D View icon, as shown in Figure 1.39.

FIGURE 1.39 The 3D View icon will be used heavily.

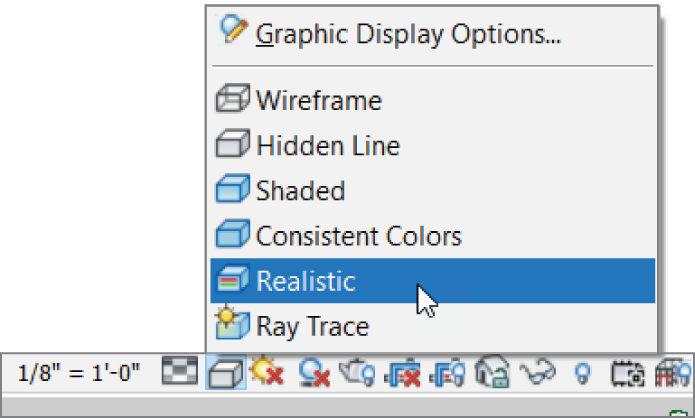

- On the View Control bar, click the Visual Style button and choose Realistic, as shown in Figure 1.40.

- Again on the View Control bar, select the Shadows On icon and turn on shadows, as shown in Figure 1.41.

FIGURE 1.40 The Visual Style button enables you to view your model in color. This is typical for a 3D view.

FIGURE 1.41 Shadows create a nice effect, but at the expense of RAM.

Within the 3D view is the ViewCube. It's the cube in the upper‐right corner of the view window. You can switch to different perspectives of the model by clicking the quadrants of the cube (see Figure 1.42).

FIGURE 1.42 The ViewCube lets you look freely at different sides of the building.

Your model should look similar to Figure 1.43. (Metric users, you do not have the concrete belt or the concrete block coursing below the brick.)

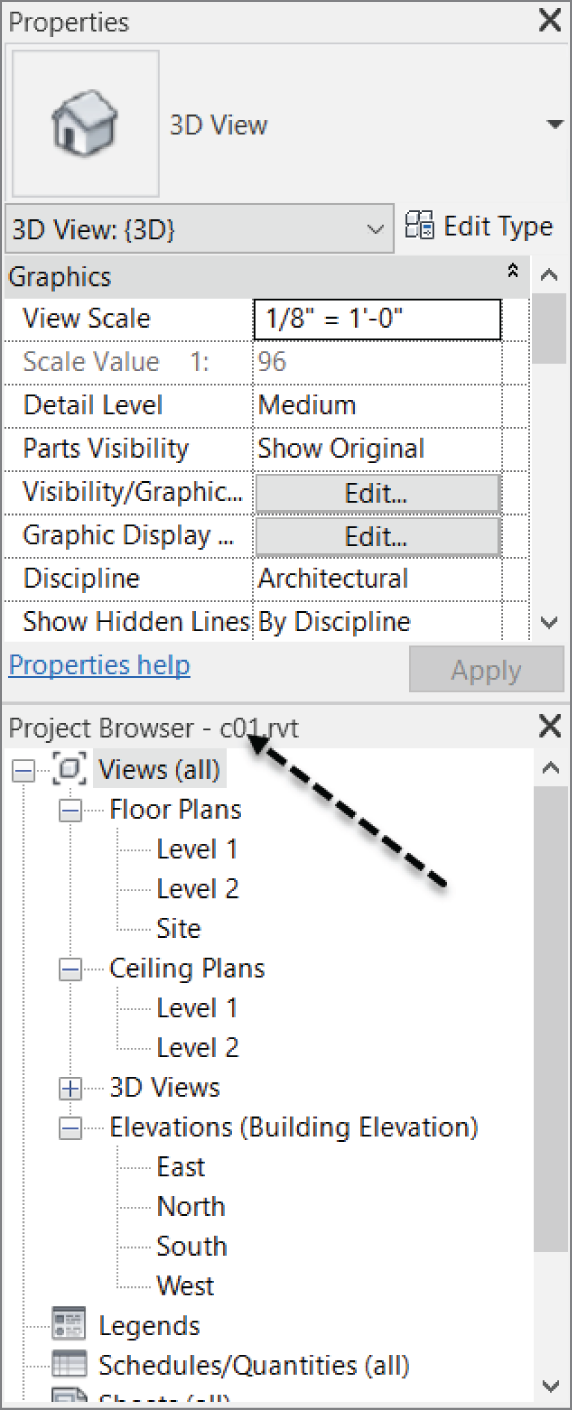

Go back to the floor plan. Wait! How? This brings us to an important topic in Revit: the Project Browser.

FIGURE 1.43 The model with shadows turned on

The Project Browser

Revit is the frontrunner of BIM. BIM has swept our industry for many reasons. One of the biggest reasons is that you have a fully integrated model in front of you. That is, when you need to open a different floor plan, elevation, detail, drawing sheet, or 3D view, you can find it all right there in the model.

Also, this means your workflow will change drastically. When you think about all the external references and convoluted folder structures that make up a typical job, you can start to relate to the way Revit uses the Project Browser. In Revit, you use the Project Browser instead of the folder structure you used previously in CAD.

This approach changes the playing field. The process of closing the file you're in and opening the files in which you need to do work is restructured in Revit to enable you to stay in the model. You never have to leave one file to open another. You also never need to rely on external referencing to complete a set of drawings. Revit and the Project Browser put it all in front of you.

To start using the Project Browser, follow along:

- To the far left of the Revit interface are the combined Project Browser and Properties dialogs. At the bottom of the dialogs, you'll see two tabs, as shown in Figure 1.44. Click the Project Browser tab.

FIGURE 1.44 The Project Browser is your new BIM Windows Explorer.

- The Project Browser is broken down into categories. The first category is Views. The first View category is Floor Plans. In the Floor Plans category, double‐click Level 1.

- Double‐click Level 2. Notice that the walls look different than in Level 1. Your display level is set to Coarse. This is because any change you make on the View Control bar is for that view only. When you went to Level 2 for the first time, the change to the display level had not yet been made.

- In the view window, you see little icons that look like houses (see Figure 1.45). These are elevation markers. (Metric users, yours are round.) The elevation marker to the right might be in your building or overlapping one of the walls. If this is the case, you need to move it out of the way.

FIGURE 1.45 Symbols for elevation markers in the plan. If you need to move them, you must do so by picking a window. There are two items in an elevation marker.

- Pick a box around the elevation marker. When both the small triangle and the small box are selected, move your mouse cursor over the selected objects.

- Your cursor turns into a move icon. Pick a point on the screen, and move the elevation marker out of the way.

- In the Project Browser, find the Elevations (Building Elevation) category. Double‐click South.

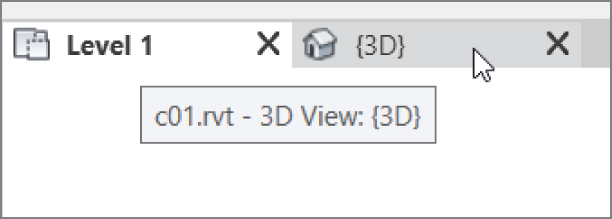

- Also in the Project Browser, notice the 3D Views category. Expand the 3D Views category, and double‐click the {3D} choice. This brings you back to the 3D view you were looking at before this exercise.

Now that you can navigate through the Project Browser, adding other components to the model will be much easier. Next, you'll begin to add some windows.

Windows

By clicking all these views, you're simply opening a view (window) of the building, not another file that is stored somewhere. For some users, this can be confusing. (It was initially for me.)

When you click around and open views, they stay open. You can quickly open many views. There is a way to manage these views before they get out of hand.

In the upper‐right corner of the Revit dialog, you'll see the traditional close and minimize/maximize buttons for the application. Just below them are the traditional buttons for the files that are open, as shown in Figure 1.46. Click the X to close the current view.

FIGURE 1.46 You can close a view by clicking the X for the view. This doesn't close Revit—or an actual file for that matter—it simply closes that view.

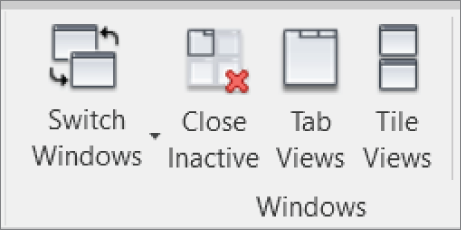

In this case, you have multiple views open. This situation (which is quite common) is best managed on the View tab. To use the Window menu, perform the following steps:

- On the Windows panel of the View tab, click the Switch Windows button, as shown in Figure 1.47.

FIGURE 1.47 The Switch Windows menu lists all the current views that are open.

- After the menu is expanded, look at the open views.

- Go to the {3D} view by selecting it from the Window menu and clicking the 3D icon at the top of the screen or by going to the {3D} view in the Project Browser.

- On the Windows panel, click Close Inactive.

- In the Project Browser, open Level 1.

- Go to the Windows panel, and select Tile Views.

- With the windows tiled, you can see the Level 1 floor plan along with the 3D view to the side. Select one of the walls in the Level 1 floor plan. Notice that it's now selected in the 3D view. The views you have open are mere representations of the model from that perspective. Each view of the model can have its own independent view settings.

- Click into each view, and type ZA. Doing so zooms the extents of each window. This is a useful habit to get into.

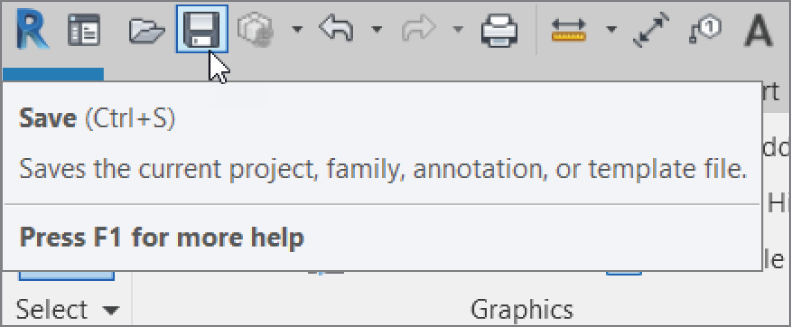

You're at a safe point now to save the file. This also brings us to a logical place at which to discuss the various file types and their associations with the BIM model.

File Types and Families

Revit has a unique way of saving files and using different file types to build a BIM model. To learn how and why Revit has chosen these methods, follow along with these steps:

- Click the Save icon (see Figure 1.48).

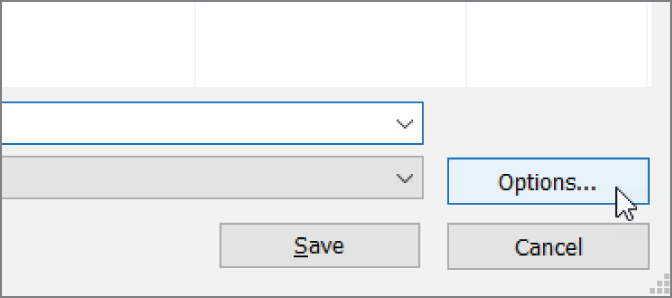

- In the Save As dialog, click the Options button in the lower‐right corner (see Figure 1.49).

FIGURE 1.48 The traditional Save icon brings up the Save As dialog if the file has never been saved.

FIGURE 1.49 The Options button in the Save As dialog lets you choose how the file is saved.

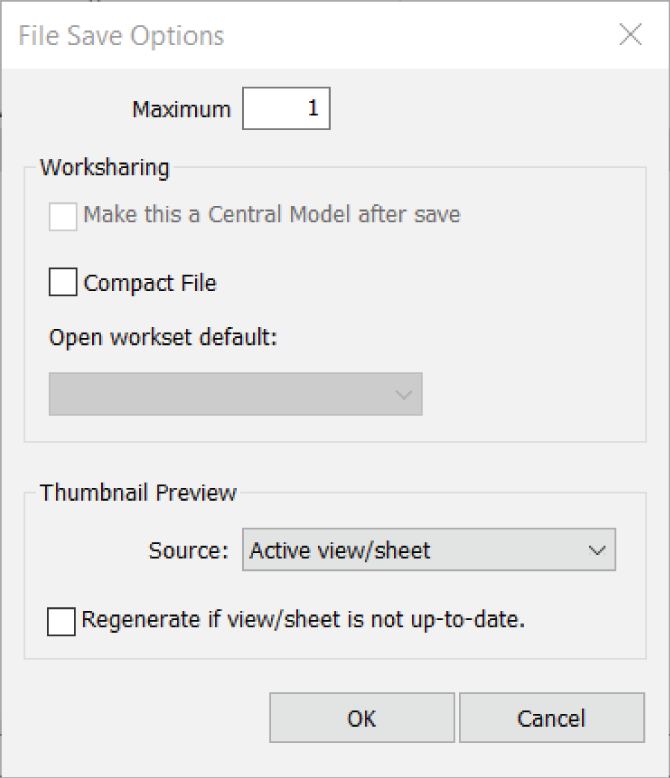

- In the File Save Options dialog is a place at the top where you can specify the number of backups, as shown in Figure 1.50. Set this value to 1.

FIGURE 1.50 The options in the File Save Options dialog box let you specify the number of backups and the view for the preview.

Revit provides this option because when you click the Save icon, Revit duplicates the file. It adds a suffix of

0001to the end of the filename. Each time you click the Save icon, Revit records this save and adds another file called0002, leaving the0001file intact. The default is to do this three times before Revit starts replacing0001,0002, and0003with the three most current files. - In the Preview section, you can specify in which view this file will be previewed. I like to keep it as the active view. That way I can get an idea of whether the file is up to date based on the state of the view. Click OK.

- Create a folder somewhere, and save this file into the folder. The name of the file used as an example in the book is

NER.rvt. (NER stands for “No Experience Required.”) Of course, you can name the file anything you wish, or you can even make your own project using the steps and examples from the book as guidelines.

Now that you have experience adding components to the model, it's time to investigate exactly what you're adding here. Each component is a member of what Revit calls a family.

System and Hosted Families (.rfa)

A Revit model is based on a compilation of items called families. There are two types of families: system families and hosted families. A system family can be found only in a Revit model and can't be stored in a separate location. A hosted family is inserted similarly to a block (or cell) and is stored in an external directory. The file extension for a hosted family is .rfa.

System Families

System families are inherent to the current model and aren't inserted in the traditional sense. You can modify a system family only through its element properties in the model. The walls you've put in up to this point are system families, for example. You didn't have to insert a separate file in order to find the wall type. The system families in a Revit model are as follows:

- Walls

- Floors

- Roofs

- Ceilings

- Stairs

- Ramps

- Shafts

- Rooms

- Schedules/quantity takeoffs

- Text

- Dimensions

- Views

System families define your model. As you can see, the list pretty much covers most building elements. There are, however, many more components not included in this list. These items, which can be loaded into your model, are called hosted families.

Hosted Families

All other families in Revit are hosted in some way by a system family, a level, or a reference plane. For example, a wall sconce is a hosted family in that, when you insert it, it's appended to a wall. Hosted families carry a file extension of .rfa. To insert a hosted family into a model, follow these steps:

- Open the

NER‐01.rvtfile or your own file. - Go to Level 1.

- On the Architecture tab, click the Door button.

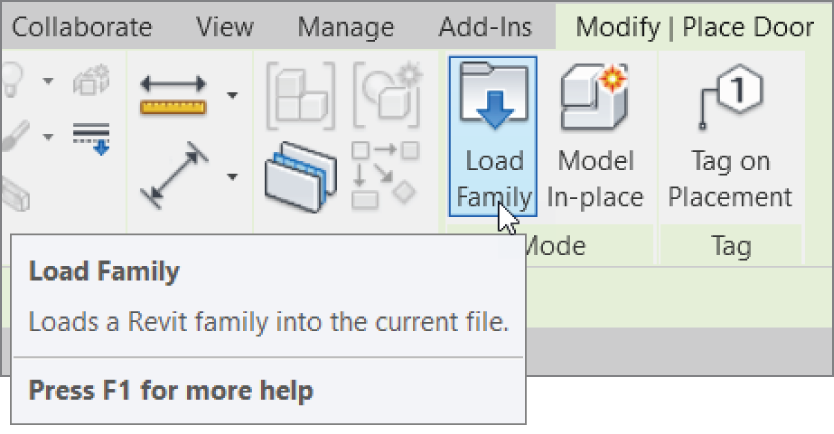

- On the Modify | Place Door tab, click the Load Family button, as shown in Figure 1.51. This opens the Load Family dialog.

FIGURE 1.51 You can load an RFA file during the placement of a hosted family.

- Browse to the

Doorsdirectory.Note that, if you're on a network, your directories may not be the same as in this book. Contact your CAD/BIM manager (or whoever loaded Revit onto your computer) to find out exactly where they may have mapped Revit.

- Notice that there is a list of doors. Open the

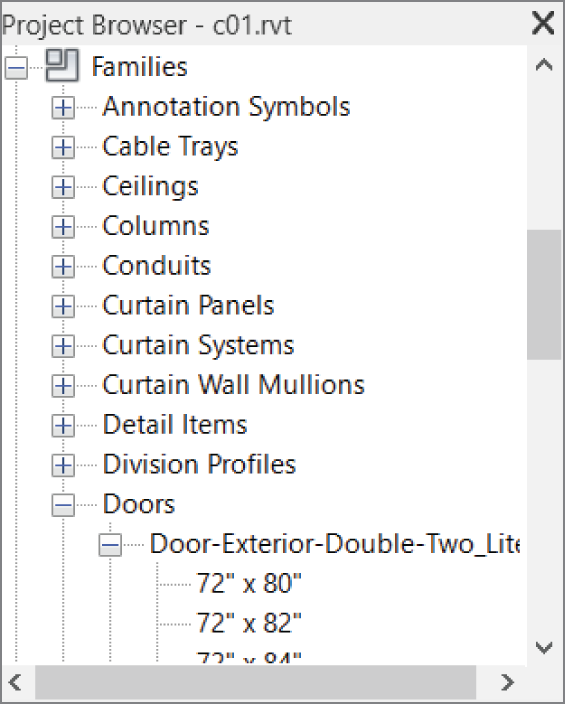

Commercialfolder, selectDoor‐Exterior‐Double_Two‐Lite.rfa, and click Open. (Metric users, selectM_Double‐Panel 2.rfa.) - In the Properties dialog, click the Type Selector, as shown in Figure 1.52. Notice that in addition to bringing in the door family, you have seven different types of the door. These types are simply variations of the same door. You no longer have to explode a block and modify it to fit in your wall.

FIGURE 1.52 Each family RFA file contains multiple types associated with that family.

- Select Door‐Exterior‐Double‐Two_Lite 72″ × 80″ as shown in Figure 1.52.

- Zoom in on the upper‐left corner of the building, as shown in Figure 1.53.

- To insert the door into the model, you must place it in the wall. (Notice that before you hover your cursor over the actual wall, Revit won't allow you to add the door to the model, as shown in Figure 1.53.) When your pointer is directly on top of the wall, you see the outline of the door. Pick a point in the wall, and the door is inserted. (We'll cover this in depth in the next chapter.)

FIGURE 1.53 Inserting a hosted family (

.rfa) - Delete the door you just placed by selecting it and pressing the Delete key on your keyboard. This is just practice for the next chapter.

You'll use this method of inserting a hosted family into a model quite a bit in this book and on a daily basis when you use Revit. Note that when a family is loaded into Revit, there is no live path back to the file that was loaded. After it's added to the Revit model, it becomes part of that model. To view a list of the families in the Revit model, go to the Project Browser and look for the Families category. There you'll see a list of the families and their types, as Figure 1.54 shows.

The two main Revit file types have been addressed. Two others are also crucial to the development of a Revit model.

Using Revit Template Files (.rte)

The .rte extension pertains to a Revit template file. Your company surely has developed a template for its own standards or will do so soon. An .rte file is the default template that has all of your company's standards built into it. When you start a project, you'll use this file. To see how an .rte file is used, follow these steps:

- Click the File Tab, and select New ➣ Project.

- In the resulting dialog, shown in Figure 1.55, click the Browse button.

FIGURE 1.54 All the families are listed in the Project Browser.

- Browsing throws you into a category with several other templates. You can now choose a different template.

FIGURE 1.55 A new Revit model is based on an RTE template file.

- Click Cancel twice.

Whenever you start a project, you'll use the RTE template. When you start a new family, however, you'll want to use an RFT file.

Using Revit Family Files (.rft)

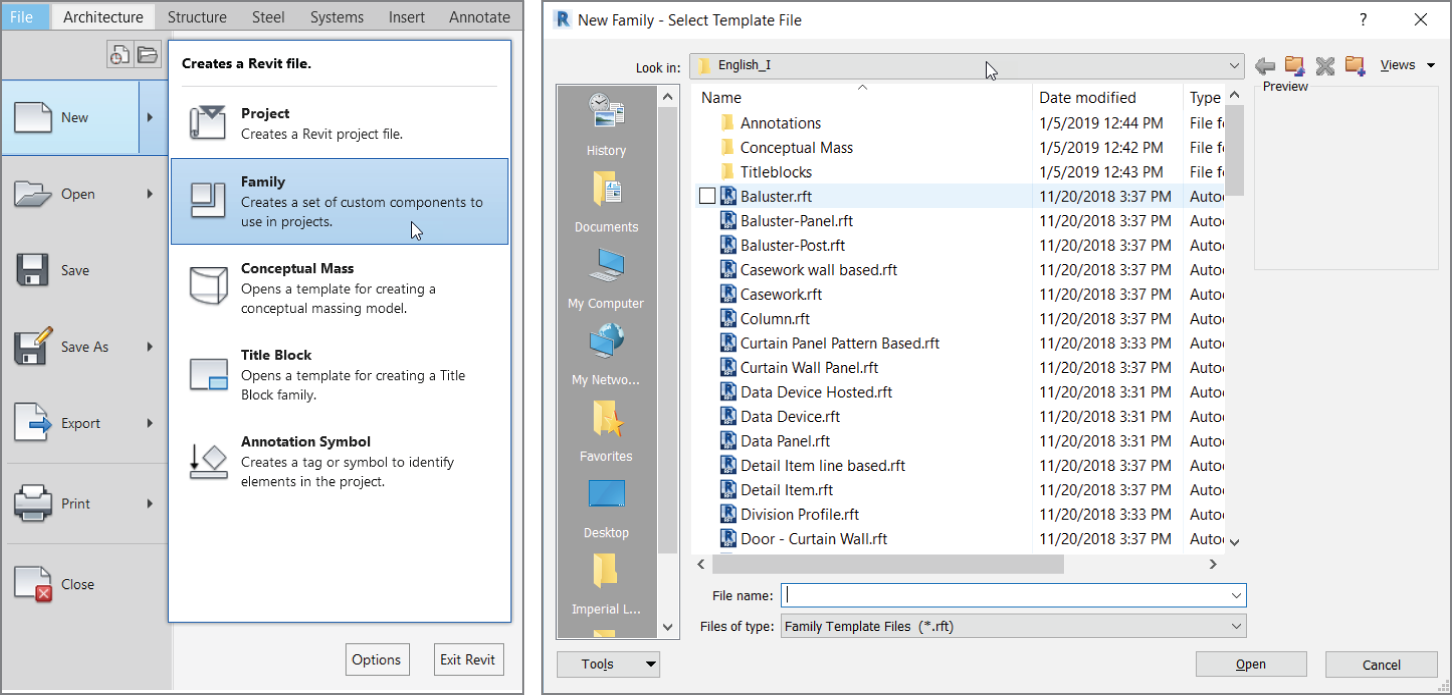

The .rft extension is another type of template—only this one pertains to a family. It would be nice if Revit had every family fully developed to suit your needs. Alas, it doesn't. You'll have to develop your own families, starting with a family template. To see how to access a family template, perform these steps:

- Click the File tab, and select New ➣ Family to open the browse dialog shown in Figure 1.56.

FIGURE 1.56 The creation of a family starts with templates.

- Browse through these templates. You'll most certainly use many of them.

- Click the Cancel button.

Are You Experienced?

Now you can…

- navigate the Revit Architecture interface and start a model

- find commands on the Ribbon and understand how this controls your options

- find where to change a keyboard shortcut to make it similar to CAD

- navigate through the Project Browser

- understand how the Revit interface is broken down into views

- tell the difference between the two different types of families and understand how to build a model using them