Chapter 11

Information Processing in Dendrites and Spines

Introduction

A central goal of neuroscience is to understand how neural circuits control sensation and action, perception, and cognition. These circuits are constructed of neurons, most of which have elaborately branching dendritic trees. Dendrites receive and integrate a wealth of information; in many cases tens of thousands of synapses are formed on the dendritic tree of a single neuron. Activation of these synapses results in complex spatiotemporal signal integration involving current flow that ultimately converges in the axon, where “decisions” are made regarding action potential initiation. Signal integration in dendrites is central to the function of neural circuits and therefore contributes to the brain’s ability to perform the multimodal integrative tasks that are key to survival. Thus, a detailed analysis of how synaptic inputs are integrated in dendrites is essential to an understanding of the neural control of behavior and cognition.

A traditional approach to investigating the function of neural circuits is through modeling of neural networks. Typically, these models are built using simple neurons that integrate excitatory and inhibitory inputs until a fixed threshold for action potential firing is reached. Some real neurons might function like this. For example, the most numerous cell type in the brain—the granule cells of the cerebellum—integrates just a few excitatory inputs on very small dendrites. In these neurons, synaptic integration is relatively simple. Most other neurons in the brain, however, have much more elaborate dendritic trees, and accordingly, synaptic integration is much more complex.

The structure of dendritic trees is very diverse (Fig. 11.1), likely reflecting diversity in the functional properties and the types of computations performed by different types of neurons. To fully understand synaptic integration and, ultimately, the computations performed by neurons and circuits, it is necessary to achieve an appreciation of how synaptic inputs are processed in a variety of neuronal types. Dendritic integration has been studied in several types of neurons, with an emphasis on pyramidal neurons of the neocortex and hippocampus and Purkinje cells of the cerebellum. From this work a number of general principles have been learned, which will facilitate the analysis of dendritic integration in other cell types as the field advances.

Figure 11.1 Variation in the structure of dendritic trees. Reconstructions are shown from: (A) alpha motoneuron of cat spinal cord, (B) spiking interneuron from mesothoracic ganglion of locust, (C) neocortical layer 5 pyramidal neuron of rat, (D) retinal ganglion cell in cat, (E) amacrine cell from retina of larval salamander, (F) cerebellar Purkinje cell in human, (G) relay neuron in basoventral thalamus of rat, (H) granule cell from olfactory bulb of mouse, (I) spiny projection neuron from striatum of rat, (J) nerve cell in nucleus of Burdach of human fetus, (K) Purkinje cell of mormyrid fish.

How does the presence of dendrites affect synaptic integration? The answer is complex, but it has its roots in the fact that the interactions between multiple synapses, and the mechanisms that ultimately lead to action potential firing in the axon, are determined by current flow both across the membrane and longitudinally along dendritic branches. Thus, a key component to understanding how synaptic inputs are integrated is to quantitatively analyze how current flows in dendritic trees. This first became possible with the development of neuronal cable theory by Wilfrid Rall (Box 11.1).

Box 11.1 Neuronal Cable Theory and Computational Modeling

One of the seminal contributions to neuroscience is neuronal cable theory, which was developed by Wilfrid Rall in the 1950s–1960s. The theory provided a framework for quantitatively analyzing the effects of dendrites and dendritic spines on the process of synaptic integration. The central concept is that dendrites are conductive cables separated from a conducting surrounding medium (the extracellular space) by a mostly insulating membrane. The cable is characterized by its intracellular resistivity (Ri), its membrane resistivity (Rm), and its specific membrane capacitance (Cm). If the membrane potential is changed at the sealed end of a cable that extends infinitely in one direction, the voltage will decay exponentially, according to the equation:

where ΔV0 is the voltage change imposed at the end, ΔVx is the voltage change at distance x along the cable, and λ is the “space constant” of the cable, given by λ = [(d/4)(Rm/Ri)]1/2, where d is the diameter of the cable. For transient voltage changes, the terminal decay of the voltage over time is governed by the membrane time constant, τ = RmCm.

The mathematical centerpiece of neuronal cable theory is the cable equation:

This differential equation describes the change in voltage along a cable in both time and space, where X and T are dimensionless variables (X = x/λ and T = t/τ). The cable equation had been used previously for axons (Cole & Hodgkin, 1939; Davis & Lorente de Nó, 1947; Hodgkin & Rushton, 1946), but Rall extended its application to dendrites. Although much of Rall’s work used this equation to analyze voltage changes in simple linear cables, he also applied it to branching cables and showed that it could be used to analyze dendrites with arbitrary branching geometries. Indeed, one of Rall’s (1959) key contributions was his analysis of the effects of branching in cables: primarily in dendrites, but also in axons (Goldstein & Rall, 1974).

In its analytical form, the cable equation can only be applied to passive dendrites with current sources (i.e., no synaptic or voltage-gated conductances). Rall realized, however, that dendrites were not likely to function as purely passive cables, so he also applied the cable equation to numerical simulations in order to facilitate simulation of more complex conditions, such as the activation of time- and voltage-dependent conductances in dendrites. Central to this approach is the concept that each segment of a dendrite can be broken up into a number of isopotential compartments, with changes in membrane potential between compartments computed using the cable equation with discrete time steps. The accuracy of such simulations therefore depends on the assignment of appropriately small compartments and short time steps.

Rall’s calculations and computer simulations provided myriad insights, including many of the principles described in this chapter. Two of them are illustrated here: the distance-dependent filtering of synaptic potentials along cables and the difference in responses to groups of synapses activated in different spatio-temporal patterns along a dendrite (Fig. B11.1). His many other findings are reviewed in the book Theoretical Foundation of Dendritic Function (Segev, Rinzel, & Shepherd, 1995), which compiles and summarizes Rall’s most important contributions to the field.

Figure B11.1 Simulations of excitatory synaptic inputs in a model dendrite. (A) Somatic membrane potential for excitatory synapses (ε) positioned in different compartments of a dendrite. Synapses positioned further from the soma resulted in progressively smaller and slower somatically recorded synaptic potentials. EPSP amplitude is normalized to the driving force and time is normalized to the membrane time constant. (B) Somatic membrane potential for activation of excitatory synapses in opposite order. For A->B->C->D the proximal synapses were activated first; for D->C->B->A the distal synapses were activated first. Synapses were simulated at temporal increments of 0.25τ.

Two other aspects of Rall’s work are just as important as his papers. First, Rall pioneered the use of computers to simulate not only single neurons but also small circuits of neurons. Second, Rall realized the importance of a close alliance between theorists and experimentalists, and his work is a testament to the progress that can be achieved using this approach.

Rall took the mathematics originally developed to describe the flow of current (and the resultant voltage changes) in transatlantic telegraph cables and applied it to branching structures, in particular dendrites. Rall’s theory is sometimes called “passive cable theory,” because it is based on the passive membrane properties of neurons (see Chapter 6). Rall recognized, however, that not all neuronal cables are passive; axons certainly are not, and at the time the theory was developed, it was already becoming clear that dendrites might also be excitable (i.e., contain voltage-gated channels that provide inward current). Rall nevertheless realized that passive cable theory could provide the necessary foundation for a more in-depth analysis of the complex processing that would occur in excitable dendrites. He also showed that cable theory could be used to develop computational models of elaborately branching dendritic trees. Computational modeling based on cable theory has taken a central place in the field of neuroscience, allowing for complex integrative processes to be analyzed quantitatively, leading to new insights and experiments that have resulted in new discoveries. In fact, in the decades that have followed Hodgkin and Huxley’s landmark experimental and theoretical analysis of the action potential and its propagation along axons, the field of dendritic integration is one of the areas in neuroscience where the combination of experimental and theoretical approaches has been employed very effectively.

Following the logical sequence pioneered by Rall, we begin by considering how the integration of synaptic inputs occurs in passive dendrites, and continue by considering how synaptic integration is affected by active dendritic properties.

Synaptic Integration in Passive Dendrites

Decades ago, Rall used his theory to predict that somatically recorded synaptic potentials would be much smaller when the activated synapses are located in distal dendrites than if the same synapses were located close to the soma. In addition, he predicted that the filtering effects of dendrites would have effects on the time course of EPSPs and the interactions between synapses. More recently, Rall’s predictions have been validated by experimental measurements, made possible by the development of methods for recording directly from the dendrites of neurons (Box 11.2).

Box 11.2 Dendritic Recording

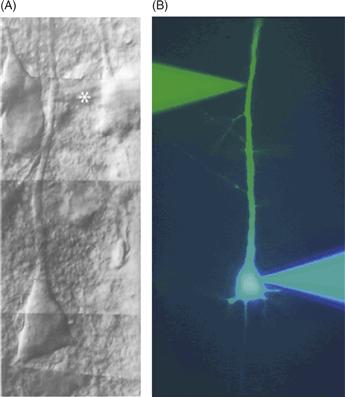

Ever since Santiago Ramón y Cajal looked down a microscope over a hundred years ago and observed that individual nerve cells have complex processes called dendrites neuroscientists have wondered at their properties. How dendrites influence the way neurons process synaptic input remained a mystery until the 1950s and 1960s, when theoretical models were used to explore dendritic function (Box 11.1). Experimental observations of dendritic properties had to wait until the 1970s and 1980s, when the first recordings were made from neuronal dendrites using sharp microelectrodes (Fig. 11.4). Due to their small size, these recordings, while very influential, were rare. Furthermore, because these recordings were performed “blind” (without visual information to guide microelectrode placement), identification of the site of recording was difficult, and recordings were restricted to brain regions where dendrites predominated.

The application of differential interference contrast optics to visualize neurons in brain slices allowed the possibility to record from neurons under visual control (Takahashi, 1978). This method was significantly enhanced by the introduction of the patch-clamp technique (Edwards, Konnerth, Sakmann, & Takahashi, 1989). Advances in optics, as well as the use of both infrared light, which reduces light scattering, and video microscopy, to enhance contrast, allowed dendrites to be visualized in living brain tissue for the first time (Dodt & Zieglgansberger, 1990). By combining these methods, it was possible to routinely record from dendrites under visual control (Stuart, Dodt, & Sakmann, 1993). This opened the door for direct experimental recordings to be made from dendrites using the power of the patch-clamp technique (Hamill, Marty, Neher, Sakmann, & Sigworth, 1981), allowing their properties and function to be investigated in detail. Using outside out and cell-attached recording, it has been possible to map the density and properties of voltage- and ligand-gated channels in the dendrites of different neuronal types. Furthermore, since both the dendrites and the cell body of neurons can be visually identified simultaneously, whole-cell recordings can be made from multiple locations on the same neuron, allowing the propagation of a variety of voltage signals in dendrites to be directly examined (Fig. B11.2).

As described in this chapter, these technical developments have led to a number of important discoveries about dendritic function in a variety of neuronal cell types, including direct observations of dendritic membrane properties, the finding that action potentials actively propagate back into the dendrites of many but not all neurons, and the description of a variety of different types of dendritic spikes and how they influence neuronal output. Critical to an understanding of how these dendritic properties influence brain function will be to determine how dendrites work in the intact brain. While we are still some way off achieving this goal, dendritic whole-cell recordings have been obtained in vivo in anesthetized preparations (Waters & Helmchen, 2004), and somatic whole-cell recordings can be obtained in awake, behaving animals (Lee, Manns, Sakmann, & Brecht, 2006). Using these methods, combined with optical techniques (Box 11.3), offers the possibility to observe dendritic activity at high resolution using the patch-clamp technique in the working brain.

Figure B11.2 Examples of dendritic recording. (A) Differential interference contrast image of a cortical layer 5 pyramidal neuron in a living brain slice from rat somatosensory cortex. A patch pipette (asterisk) can be seen recording from the main apical dendrite. (B) Fluorescent image of a simultaneous somatic (blue) and dendritic (green) patch pipette recording from a cortical layer 5 pyramidal neuron.

(A) Adapted from Stuart, et al., 1993; (B) Adapted from Stuart and Sakmann, 1994.

Effects of Dendrites on Synaptic Potentials at the Soma

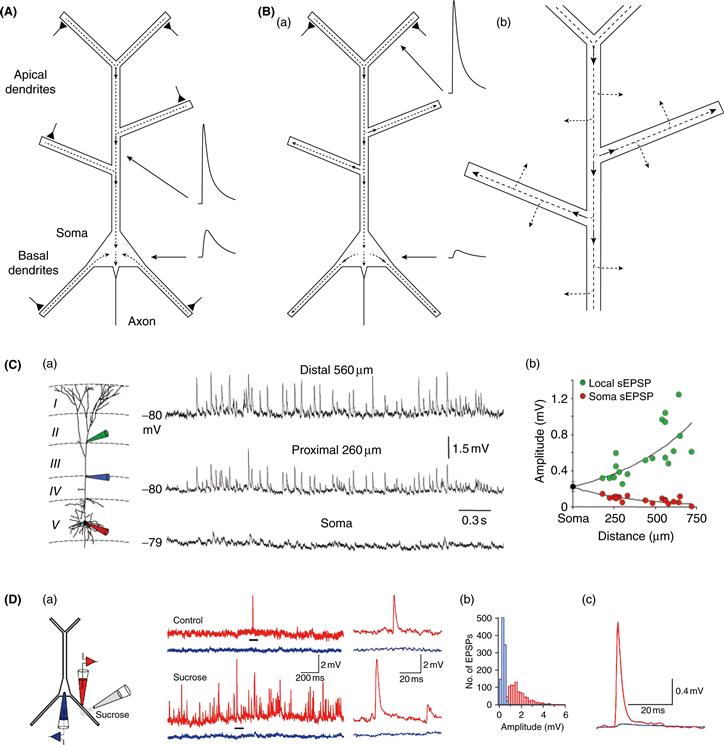

In most neurons, the soma is an important location for a number of reasons. Dendrites converge on the soma, forming a confluence for current flowing from the dendrites (Fig. 11.2A). Current that reaches the soma flows from there to the axon, which usually emerges at or very near the soma. This integrated current changes the membrane potential in the axon initial segment, where action potentials are initiated if the depolarization is sufficiently large. The soma also happens to be the location at which most electrophysiological recordings are obtained. This is convenient, because somatic recordings reflect the integration occurring at a location very near the action potential initiation zone, but it is important to understand how the presence of dendrites influences the current flowing into and out of the soma and how this shapes the membrane potential that is recorded there. The magnitude of the dendritic filtering of synaptic potentials depends on the overall structure of the dendritic tree, the membrane properties of dendrites, and the location of the synapses. In most neurons, dendrites exert a powerful filtering effect on synaptic potentials spreading through them, and as a result somatically recorded potentials are much smaller than the same events recorded in the dendrites (Fig. 11.2).

Figure 11.2 EPSPs are larger in dendrites than in the soma. (A) Schematic diagram of a pyramidal neuron illustrating synaptic current from the dendrites converging at the soma. Triangles indicate active excitatory synapses. Dashed lines indicate axial dendritic current, with arrowheads indicating direction of current flow. Schematic showing attenuation of EPSP from dendrite to the soma. Dendritic EPSP is larger than somatic EPSP because of higher input impedance of dendrite than soma and loss of charge between dendrite and soma. (B) (a) Similar to A, but showing different current flow when only distal apical synapses are activated. Dendritic EPSP is larger than in A because of higher input impedance of distal dendrite. Somatic EPSP is smaller than in A both because of fewer synapses and maximal loss of charge from distal dendrites. (b) Magnified view showing that some of the current flowing in dendrites is also lost across the dendritic membrane leak. Some membrane current would also flow in A. (C) (a) Triple whole-cell patch-clamp recordings from the soma, proximal dendrite, and distal dendrite. Spontaneous EPSPs were measured simultaneously at all three recording locations. (b) Amplitude of spontaneous EPSPs (sEPSP) measured locally and at the soma, as a function of sEPSP generation (i.e., the dendritic recording location at which the sEPSP was largest). (D) (a) Dual whole-cell patch-clamp recordings from the soma (blue) and a basal dendrite (red, 124 μm from soma) of a layer 5 neocortical pyramidal neuron. Sucrose was applied to evoke unitary EPSPs (by enhancing vesicle release), which are measured in the dendrite and soma. Traces at right are expansions of regions indicated by black bars. (b) Histogram of EPSP amplitudes measured in the soma (blue) and dendrite (red). (c) Average of EPSPs measured in the soma and dendrite.

(A, B) N. Spruston; (C) Williams and Stuart, 2002; (D) Nevian et al., 2007.

Two effects influence the difference between somatic and dendritically recorded EPSPs. First, some of the charge that enters the neuron at a synapse never reaches the soma. When a synapse depolarizes a dendrite, there is a voltage difference between the dendrite and the soma, which will promote current flow toward the soma (where the direction of current flow is defined by the movement of positive charge). Current travels within dendrites via electron transfer between charged particles in the cytoplasm, but because the density of charged particles is relatively low (compared to a copper wire, for instance), dendrites have a significant longitudinal resistance. As a result, some current will flow along alternate paths, such as onto the capacitance of the dendritic membrane and across its resistance (Fig. 11.2B). Most dendritic trees have a lot of branches and a large surface area, so there can be significant loss of synaptic current as it flows into dendritic branches on its way to the soma. In fact, in many cases only a small fraction of the total synaptic current reaches the soma and contributes to the local depolarization observed there.

Computational analyses, based on realistic models of pyramidal neurons with complex dendritic trees, suggest that for the most distal synapses on a pyramidal neuron, less than 10% of the synaptic charge will ultimately reach the soma. The same computational analyses, however, have shown that EPSPs in the soma are 100-fold smaller than the same EPSPs measured in distal dendrites, as observed in experiments (Fig. 11.2C and 11.2D). Why is there a 100-fold difference between dendritic and somatic EPSP amplitude if 10% of the synaptic charge reaches the soma? This is because a second factor influences the size of the EPSP at each location: the local input resistance (or impedance, the frequency-dependent equivalent of resistance). Small-diameter dendrites have very high input impedances, while the soma typically has a much lower input impedance, because of its larger size. Ohm’s law dictates that a given amount of synaptic charge will produce a much larger EPSP in high-impedance dendrites than in the low-impedance soma, even if no charge were lost via alternative pathways.

These two effects—charge loss and difference in local input impedance—combine to produce very large differences between the amplitude of the EPSP at the synapse and at the soma. In passive dendrites, when comparing the ability of two synapses at different locations to depolarize the soma or axon (thereby influencing action potential initiation), only the first effect is relevant, because it is the amount of charge reaching the soma that matters. Distal synapses are located on small dendrites with high input impedance, which magnifies the local voltage change, thus resulting in very large local EPSPs, but in passive dendrites this does not increase the efficacy of a synapse on action potential generation, because irrespective of whether a synapse is on the soma or on a distal dendrite, the amplitude of the somatic EPSP is determined solely by the synaptic charge that reaches the soma and the somatic input impedance. In the case of passive dendrites, only the extent to which synaptic charge is lost as current flows from the synapse to the soma affects the final impact of a distal synapse on action potential output. Thus, in the example above, the distal dendritic synapse would be only 10-fold less effective at depolarizing the soma than the same synapse located on a very proximal dendrite. As a result, it is important to realize that, in the passive case, the larger local voltage produced by more distal synapses does not in any way compensate for the distal location of these synapses, since this does not increase the amount of charge that flows into the cell at the synapse. In fact, the larger local voltage change in distal dendrites will reduce the electrical driving force for current flow at the synapse or, alternatively, may lead to activation of voltage-gated channels—important effects that are discussed later in the chapter.

Effects of Synaptic Kinetics on Dendritic Filtering

Another factor that affects the difference in amplitude of synaptic potentials in the dendrites versus the soma is the kinetics of synaptic current. As discussed in Chapter 6, current flow across the membrane is frequency dependent because of the membrane capacitance. Charge that is deposited onto the membrane capacitance can reach the soma eventually, but it is delayed. Thus, although the total amount of charge reaching the soma is not dependent on the kinetics of the synaptic current, the peak of the EPSP is attenuated more for fast synaptic potentials, such as EPSPs mediated by synchronous activation of AMPA-type glutamate receptors (GluRs), than for slow synaptic potentials, such as EPSPs mediated by activation of NMDA receptors.

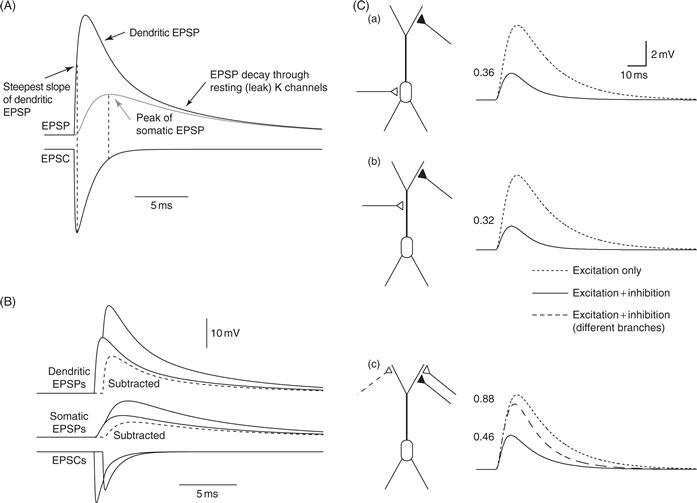

The time course of synaptic potentials is faster in the dendrites than for a similar synaptic input to the soma (Fig. 11.3A); the time course of an EPSP in a dendritic spine is expected to be even faster. Near the synapse, membrane potential rises rapidly during synaptic current, owing to the rapid onset of synaptic currents. The decay of the dendritic EPSP is also quite fast as a result of current flowing axially along the dendrites, away from the synapse (Fig. 11.2B). The somatic EPSP is much slower, however. Its rise time is slower because of the delayed arrival of synaptic current from the dendrites and its decay, like the terminal decay of the dendritic EPSP, is relatively slow because it is governed by the membrane time constant (Fig. 11.3A), which is relatively slow because of the high membrane resistance and capacitance in most neurons (see Chapter 6). These factors combine to produce relatively slow EPSPs at the soma, resulting in a longer time window for summation of synaptic potentials in the soma than in the dendrites.

Figure 11.3 Synaptic interactions in passive dendrites. (A) Simulations showing the temporal relationship between the EPSP and the EPSC. Note the steepest slope of the dendritic EPSP occurs at the peak of the EPSC. The peak of the somatic EPSP occurs when the EPSC is very small (equal to leak current). The terminal decay of the EPSP (somatic and dendritic) is governed by the membrane time constant, but the initial decay of the dendritic EPSP is faster because of axial flow of current in the dendrites, away from the synapse. Amplitude scale is arbitrary. (B) Nonlinear summation of EPSPs in passive dendrites. Simulation of two excitatory synapses activated 0.75 ms apart. EPSPs and EPSCs are shown for activation of one synapse and activation of both synapses. Dashed line: arithmetic difference between EPSP for two synapses and one synapse. The single EPSP is about 20 mV; thus, the driving force for the second EPSC is reduced by about 33%, and the EPSPs and EPSCs are accordingly smaller. (C) Simulations of the effects of inhibition on a simple pyramidal cell model. Solid lines indicate response to excitation and inhibition. Inhibition slightly precedes excitation, but has a reversal potential equal to the resting potential, thus not producing any hyperpolarization on its own (i.e., only shunting inhibition). Dotted lines are excitation alone; dashed line is excitation and inhibition for alternate location of inhibition. Numbers indicate ratio of inhibited/uninhibited EPSP. (a) Distal excitation and somatic inhibition. (b) Distal excitation and on-path dendritic inhibition. (c) Distal excitation and distal dendritic inhibition, either on the same branch as excitation or on a different branch.

(A, B) Simulations by W.L. Kath and N. Spruston; (C) Spruston et al., 2008.

A special case that needs to be considered is experiments where an attempt is made to measure synaptic currents using voltage clamp. In order to obtain accurate measures of the amplitude and kinetics of synaptic currents, it is essential that the activated synapse be located very close to the voltage-clamp electrode. When attempting to voltage clamp synapses on distal dendrites using a somatic electrode, the resultant errors are very large (so-called “space-clamp” errors). Not only are the amplitude and kinetics of the synaptic current affected by the same factors as those described above for the filtering of synaptic potentials, but an additional error is caused by the difficulty of actually clamping the synaptic membrane potential using a somatic electrode. The distance between the somatic electrode and the synapse makes it impossible for the voltage clamp to control the voltage at the synapse, resulting in “voltage escape” at the synapse. This problem is greatest for fast synapses. Space-clamp errors—caused by loss of current from synapse to soma and escape of the synaptic potential from the voltage clamp—combine to produce very large distortions of the amplitude and kinetics of synaptic currents. The magnitude of these errors has been predicted and estimated using computational models but also validated using direct experimental measurements involving simultaneous dendritic and somatic recordings.

Interactions between Synapses in Passive Dendrites

If synapses were only activated one at a time, most cells would never fire an action potential. This is because the concerted action of many excitatory synapses is required to span the gap between the resting potential and action potential threshold. This gap is typically around 20 mV, so with an average EPSP amplitude of 0.2 mV, we can estimate that about 100 excitatory synapses would need to be activated to generate an action potential. This is at best a crude estimate, however, because it fails to take into account the influence of complexities such as inhibition, dendritic filtering, changes in driving force, and dendritic excitability. It is clear that interactions that occur between synapses in dendrites play a critical role in determining the impact of EPSPs on action potential output. While these interactions can be very complicated, a few simple principles can be described.

The first important point is that excitatory synapses summate in a sublinear fashion in passive dendrites (Fig. 11.3B). The reason for this is simple. If the resting potential of a neuron is –60 mV and the reversal potential of an excitatory synapse is 0 mV, then each synapse has a driving force of 60 mV. However, if enough synapses are activated to depolarize the dendrite to –40 mV, for example, the next activated synapse will have a driving force of 40 mV, which is 33% less than if that synapse were activated on its own. In other words, when multiple excitatory synapses are activated, each synapse has a reduced driving force compared to when it is activated on its own. It is not instructive to think of excitatory synapses as inhibiting each other because they always depolarize the neuron toward threshold for action potential firing; they can never do otherwise, but in passive dendrites the effect of activating multiple excitatory synapses is always less than the sum of the effects of each synapse individually.

A second important principle is that the magnitude of this sublinearity depends on the distance between the synapses. The same physical principles that govern the attenuation of EPSPs as they propagate to the soma also influence the extent of sublinear summation of activated synapses, as the depolarization experienced by one synapse depends on its distance from the other activated synapses. If the two synapses are close together, they have a strong influence on each other’s driving force, and their summation will be sublinear. On the other hand, if the synapses are far apart on the dendritic tree, each affects the other only minimally, so the net effect of activating both synapses will be closer to their linear sum.

When the interactions between synapses include inhibition, a third important principle is that “on-path” inhibition is more effective than “off-path” inhibition (Fig. 11.3C). Here, the “path” runs from the excitatory synapses in the dendrites to the action potential initiation zone in the axon. In order to effectively inhibit action potential initiation, inhibitory synapses must reduce the current that would have otherwise depolarized the action potential initiation zone. This happens best for on-path inhibition.

When considering inhibition, it is important to realize that inhibitory synapses can be effective even if they produce little or no hyperpolarization of the membrane potential on their own. This is often referred to as “shunting inhibition.” This occurs most obviously when the reversal potential of an inhibitory synapse is the same as the resting potential. When activated on its own, such an inhibitory synapse has no effect on the membrane potential, because there is no driving force for current flow through the activated channels. When activated together with excitatory synapses, however, the inhibitory synapse shunts the current from the excitatory synapse, thus reducing the resultant somatic depolarization. In this scenario, the depolarization from the excitatory synapse creates a driving force for current flow through the inhibitory synapse. As a result, the depolarizing effect of Na+ ions entering through excitatory channels (e.g., AMPA receptors) is reduced by the hyperpolarizing effect of Cl− ions entering through the inhibitory channels (GABAA receptors).

Functional Implications of Dendritic Filtering

The fact that synaptic potentials are filtered between the synapse and the soma, affecting both their amplitude and time course, has important functional implications for synaptic integration. As mentioned above, excitatory synapses located on distal dendrites of large neurons (such as pyramidal neurons) are expected to produce somatic EPSPs that are less than one-tenth that of their more proximal counterparts. This means that in many neurons, such as pyramidal neurons of the CNS, activation of a single distal synapse could have an almost negligible effect at the soma.

Although distal synapses are expected, based on theoretical considerations, to have reduced impact at the soma compared to more proximal synapses, it is possible that at least some distal synapses might compensate for this disadvantage by having more AMPA receptors than more proximal synapses. While there is some experimental evidence that this is the case in CA1 pyramidal neurons, this is not a general principle of synaptic organization. In fact, reconstruction of synapse morphologies using serial-section electron microscopy has indicated that most (~80%) of the synapses on CA1 pyramidal neurons are very small, and immunostaining has indicated that these small synapses have very few AMPA receptors. The other 20% of the synapses have much larger PSDs and a higher density of AMPA receptors. These synapses are likely to have a larger impact at the soma. Evidence exists that they are more numerous in distal dendrites than in proximal dendrites, but they are nevertheless a minority. What is the purpose of covering dendrites with a large number of synapses that are very small? While it is true that if enough (e.g., hundreds) of these weak synapses are activated, they could indeed result in action potential initiation in the axon, it seems equally likely that these distal synapses have a different role. One possibility is that these synapses represent a large pool of synapses that can be recruited for conversion to the more powerful class of synapses through synaptic plasticity such as LTP. Another possibility, however, is that even small synapses can have significant local effects, because of the magnification of local potential by the high impedance of small dendritic branches, thus resulting in activation of dendritic voltage-gated channels. For this reason, to answer the question of how distal synapses influence the processes of synaptic integration and action potential generation, it is necessary to consider the more complex case of synaptic integration in active dendrites.

Synaptic Integration in Active Dendrites

The foregoing discussion was based on considering how synaptic potentials are integrated in passive dendrites. While this serves as a good starting point for understanding synaptic integration, another layer of complexity exists: in every dendrite where neuroscientists have looked, voltage-gated channels have been found. Among the most important of these dendritic channels are voltage-gated Na+ channels (Nav), Ca2+ channels (Cav), and K+ channels (Kv). These channels have been observed in dendrites using immunostaining of the channels with both light and electron microscopy, and their functional properties have been studied using dendritic patch-clamp recording and imaging. The identification of these channels in dendrites using modern methods that allowed direct observation of the channels validated earlier studies that inferred the excitability of dendrites from the properties of extracellular field potentials.

Intracellular recordings have also been used to study dendritic excitability. Initially, these recordings were performed using sharp microelectrodes (Fig. 11.4). More recently, however, whole-cell patch-clamp recordings have been obtained from dendrites (Box 11.2). Most of these experiments have been performed using in vitro brain-slice preparations, but some dendritic recordings have also been obtained in vivo. In addition to single whole-cell recordings, simultaneous recordings have been performed from multiple locations on the same neuron, facilitating careful analysis of the relative size and timing of various events (e.g., EPSPs, IPSPs, spikes) in different parts of the neuron.

Figure 11.4 Early examples of dendritic recordings. (A) Dendritic and somatic recordings obtained from cerebellar Purkinje neurons (composite of separate recordings). Large action potentials at the soma are severely attenuated in the dendrites. Distal dendritic recordings show large, slow spikes mediated by Cav channels. (B) Recordings from dendrites of CA1 pyramidal neurons in intact slices (top) and after separation of dendrites from somata (bottom). All traces are responses to current steps. The rightmost trace is a temporally expanded view of the response to the left.

Dendritic excitability has now been studied in several cell types, but the ones most intensively studied are pyramidal neurons (hippocampal CA1 and neocortical layer 5 and layer 2/3) and cerebellar Purkinje cells. Studies of these and other neurons have revealed that the excitable properties of dendrites depend on the cell type. For example, CA1 pyramidal neurons are quite different from layer 5 pyramidal neurons, and Purkinje cells are even more different (as one might expect from the very distinct morphology of their dendritic tree). Despite differences between neuronal types, it is possible to extract a number of important general principles from these studies.

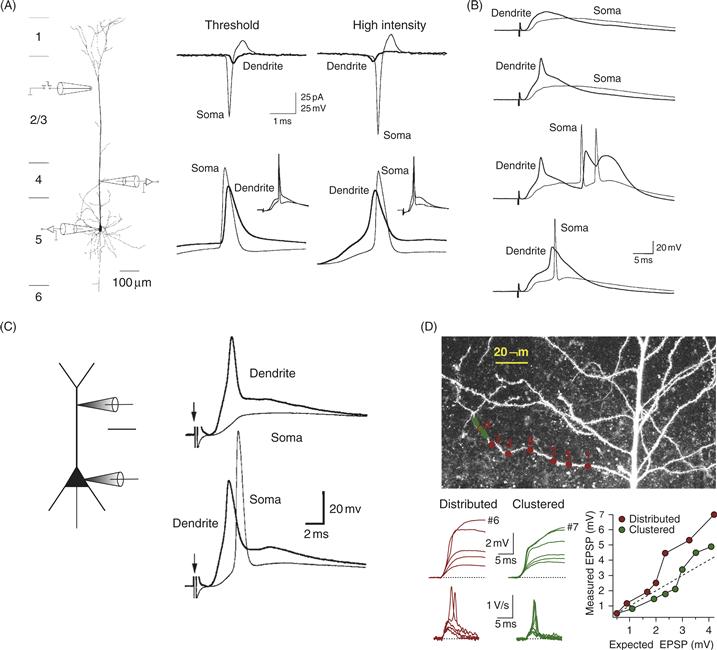

Weakly Excitable Dendrites and Backpropagating Action Potentials

One of the central principles is that dendrites are weakly excitable; that is, they contain voltage-gated channels that can support action potential propagation and dendritic spike generation, but they are not as excitable as the axon. The most direct evidence for this comes from studies involving simultaneous recording from the soma and a dendrite. These experiments have revealed that action potentials occur first in the axon and later in the soma and dendrites (Fig. 11.5). This is true even when the stimulus leading to the action potential is dendritic (e.g., activation of synapses near the dendritic recording electrode). This result has been interpreted to indicate that the action potential is initiated in the axon (in the axon initial segment), then “backpropagates” into the soma and dendrites. Indeed, experiments involving simultaneous recording from the axon and the soma have revealed that the axonal action potential precedes the somatic action potential, again confirming earlier conclusions based on extracellular recordings. Thus, the axon appears to have a much lower threshold for action potential initiation than the dendrites. The low axonal threshold results from the fact that, compared to the dendrites, the axon has a much higher density of Nav channels and possibly a higher density of Kv channels.

Figure 11.5 Backpropagating action potentials. (A) Triple recording from a neocortical layer 5 pyramidal neuron shows action potential initiation in the axon and backpropagation into the soma and dendrites. (B) Simultaneous dendritic recording from soma and dendrites of cerebellar Purkinje cell shows severe attenuation of action potentials recorded in the dendrites, regardless of the site of current injection. (C) Variable amplitude attenuation of backpropagating action potentials in different types of neurons. (D) Simulations of backpropagating action potentials in CA1 pyramidal neurons reveal sensitivity to Nav and Kv channel density in the distal dendrites, which determines whether or not the action potential successfully invades the apical dendritic tuft. The model shown on the right has a higher density of dendritic Nav channels than the model on the left.

(A) Häusser et al., 2000; (B) Stuart and Häusser, 1994; (C) Stuart et al., 1997b; (D) Golding et al., 2001.

Another observation indicating that dendrites are only weakly excitable is that backpropagating action potentials tend to attenuate as they propagate (Fig. 11.5). Dendritic recordings have revealed that the amplitude of the backpropagating action potential decreases with distance from the soma. The steepness of this attenuation (amplitude as a function of distance), however, varies between cell types. Pyramidal neurons have intermediate attenuation, while Purkinje cells exhibit much greater attenuation and dopamine neurons in substantia nigra have almost no attenuation. The degree of attenuation depends on two factors. One is the density and ratio of Nav and Kv channels, and the other is the amount of branching in the dendritic tree. Branch points create impedance mismatches and capacitance loads, which means more current is required to support reliable propagation of the action potential through each branch point. This effect can be small for individual branch points, but the cumulative effect of many branch points can be very significant. For example, in cerebellar Purkinje cells, there are so many branch points that active action potential backpropagation is completely inhibited. Though this is in part due to the low density of Nav channels in Purkinje cell dendrites, simulations have shown that very high densities of Nav channels would be required to overcome the extensive branching in these dendrites.

Most of our knowledge about the amplitude of backpropagating action potentials at different distances from the soma comes from dendritic patch-clamp recording. Because these recordings have mostly been made from relatively large-diameter dendrites, less is known about the amplitude of backpropagating action potentials in smaller dendrites, such as basal, apical oblique, or apical tuft branches in pyramidal neurons or the fine branchlets of Purkinje cells. It is extremely difficult to place electrodes on such small dendrites, so imaging is a valuable complement to electrophysiological recording (Box 11.3). Indeed, imaging experiments have provided experimental support for the notion that even small-diameter dendrites are excitable.

Box 11.3 Imaging Dendritic Function

The microscope was for a long time the only method by which experimentalists could gain information about the properties of dendrites, though the information yielded by light and electron microscopes was initially purely structural. The advent of dendritic microelectrode recording in the 1970s, and subsequently patch-clamp recording from dendrites in the 1990s (see Box 11.2), transformed our view of the functional properties of dendrites, offering us direct information about the electrical events taking place within the dendritic tree. Over the last 15 years, however, a variety of new imaging techniques have emerged as alternatives to electrophysiological approaches for investigating the functional properties of dendrites. Using light to probe function has several key advantages over conventional electrophysiological techniques (Scanziani & Häusser, 2009): light is noninvasive in that it normally does not interact with neurons; it can penetrate deep into tissue; offers outstanding spatial resolution; can permit detection of single molecular events; allows simultaneous measurement from multiple locations; and, crucially (with the advent of genetic and subcellularly targetable probes), permits recording from specific cell types and precisely defined subcellular compartments.

Early approaches for harnessing the power of imaging to probe the functional properties of dendrites involved the use of fluorescence microscopy, using confocal microscopes, CCD cameras, or photodiode arrays. In conjunction with the use of sensitive calcium indicators, introduced into the cell by microelectrodes, these approaches permitted the investigation of calcium signaling in distal dendrites, and even individual dendritic spines, to be probed for the first time. Calcium has often been used as a surrogate for electrical activity, particularly in compartments inaccessible to recording electrodes, but with the caveat that Ca2+ signals are affected not just by membrane potential, but also by other factors, including channel density, surface-to-volume ratio, and Ca2+ buffering and transport. Of course, calcium dynamics have also been studied in their own right due to the immense importance of calcium as a biochemical signalling molecule. The advent of improved voltage-sensitive dyes, together with faster and more sensitive CCD cameras, has more recently enabled voltage-sensitive dye measurements to be made directly from dendrites, allowing direct measurements of voltage in small dendritic compartments (though with limitations due to intracellular compartmentalization of dye; lack of calibration in distal dendrites; and problems with dye toxicity).

A fundamental breakthrough in using light to probe dendritic function came with the invention of two-photon microscopy (Denk & Svoboda, 1997). This approach harnesses the highly nonlinear nature of two-photon absorption to limit excitation to a tiny (femtoliter) volume, permitting high-resolution imaging deep within tissue (Fig. B11.3). Two-photon microscopy has been applied to study the structural and functional properties of dendrites and spines both in brain slices and more recently also in vivo (see Figure; Denk & Svoboda, 1997). It has led to numerous important discoveries both about the morphological and functional dynamics of dendritic spines as well as information processing within the dendritic tree. Furthermore, two-photon microscopy allows patch-clamp recordings to be targeted to particular cell types, and even to individual dendrites, and also allows recording locations to be verified with high precision, both in brain slices and in vivo, and has thus become an indispensible tool for dendritic physiologists. Recent developments in the miniaturization of two-photon optics have enabled imaging of neuronal calcium signals in freely moving animals equipped with head-mounted two-photon microscopes.

Figure B11.3 Using optical techniques to probe dendritic function. (A) A cuvette filled with a fluorescent dye is illuminated with either one-photon or two-photon excitation (top and bottom objectives, respectively). Note the remarkable spatial precision of the two-photon excitation. (B) In vivo imaging of dendritic calcium signaling. Left, a single layer 2/3 pyramidal cell in an anaesthetized rat is filled with a calcium dye (Oregon Green BAPTA-1) via a somatic patch-clamp recording and imaged using 2-photon microscopy. Right, Ca2+ transients (averages of 3–5 trials) that were evoked by single backpropagating action potentials at the positions indicated along the dendrite. (C) Probing computational properties of single dendrites using two-photon glutamate uncaging. (a) A pyramidal cell in a neocortical slice is filled with a fluorescent dye via a somatic patch pipette. (b) Spines along a single dendrite are imaged using two-photon microscopy, and the dendrite is bathed with a caged glutamate compound (MNI-glutamate). Synaptic transmission is then mimicked by brief two-photon uncaging at individual spines (yellow dots). (c) The synapses are activated in a sequence, either moving towards the soma (ON, red trace), or away from the soma (OFF, blue trace), producing a directionally selective EPSP at the soma.

(A) Courtesy of Brad Amos, MRC, LMB, Cambridge; (B) Waters et al., 2003; (C) Branco et al., 2010.

Another important optical approach for probing dendritic function is the use of two-photon excitation for uncaging of neurotransmitters, which in conjunction with appropriate cages now allows individual glutamatergic and GABAergic synapses on dendrites to be activated with high temporal and spatial precision. This approach has allowed the input-output function of individual dendrites to be probed with unrivalled temporal and spatial precision (e.g., Branco, Clark, & Häusser, 2010) and has also permitted the investigation of dendritic plasticity rules.

There is currently tremendous enthusiasm about the use of imaging techniques for examining dendritic function, driven by advances in microscope resolution (Hell, 2007), innovative sample preparation (Micheva & Smith, 2007), and development of new sensors (Miyawaki, 2011). In particular, the advent of new genetically encoded probes for calcium, voltage, and a variety of signal transduction molecules, as well as the ability to target these probes to specific cell types and/or subcellular compartments, promise to offer us unprecedented insights into both electrical and chemical signaling in the most distal corners of dendritic trees. While electrophysiological approaches will probably always maintain their status as the “gold standard” for investigating electrical signaling in dendrites, due to their superior sensitivity and temporal resolution (Scanziani & Häusser, 2009), it is clear that optical solutions for probing dendritic function will become increasingly popular.

Nonuniform Distribution of Voltage-Gated Channels in Dendrites

Another important principle of dendritic excitability is that the expression of voltage-gated channels is not uniform across the dendritic tree. The two best-characterized examples of this are the A-type Kv channels (Kv4) in CA1 pyramidal neurons and the hyperpolarization-activated cation (HCN) channels in CA1 and layer 5 pyramidal neurons. Patch-clamp recordings from these currents have shown that both channel types have much higher densities in distal apical dendrites than in the soma or proximal apical dendrites. Immunostaining has verified and extended these findings, but important questions remain about the distribution of these and other channels. Numerous challenges must be overcome before we can determine the distribution and functional properties of voltage-gated channels in dendrites from which direct recordings are very difficult. These challenges include questions about antibody specificity, difficulty distinguishing proximal versus distal dendrites when they are overlapping (as in apical oblique branches of pyramidal neurons), or expression of channels in closely apposed presynaptic and postsynaptic structures (e.g., boutons and spines). Furthermore, expression does not always equate to function, so while staining methods can in principle tell whether or not a channel type is present in a particular dendrite, staining cannot be used to determine if the observed channels are functional and, if so, what their specific properties are.

The nonuniform expression of voltage-gated channels in dendrites is likely to have significant functional implications. This is best understood for the case of Kv4 channels in CA1 pyramidal neurons, where the increasing density at more distal locations contributes to the distance-dependent attenuation of backpropagating action potentials and raises the threshold for generation of dendritic spikes in these neurons (see below). Because there are so many different types of channels (e.g., low- and high-threshold Cav channels; Ca2+-activated K+ channels), determining the subtypes, distribution, and properties of these channels in dendrites of different types of neurons will be critical to a better understanding of how synaptic inputs are integrated in the brain.

Dendritic Spikes

Although the lowest threshold for action potential initiation is in the axon, most dendrites can generate dendritic spikes (Figs. 11.6 and 11.7). Because of the weakly excitable nature of the dendritic tree, dendritic spikes have a relatively high voltage threshold. Recall, however, that dendrites locally magnify synaptic potentials because of their high input impedance. Thus, even a small number of synapses can produce local depolarizations that are large enough to activate voltage-gated channels in the dendrites.

Figure 11.6 Dendritic sodium spikes. (A) Simultaneous somatic and dendritic (175 μm from soma) recordings from a neocortical layer 5 pyramidal neuron. Using synaptic stimulation at threshold for action potential initiation (left), the somatic action potential precedes the dendritic action potential, both in cell-attached (top) and whole-cell (bottom) recordings. At higher synaptic stimulus intensity (right) the action potential occurs first in the dendrites. (B) Similar recording configuration with dendritic recording 440 μm from the soma. Example traces show (top to bottom): subthreshold EPSP, isolated dendritic spike, dendritic spike followed by somatic burst, dendritic spike preceding somatic action potential. (C) Somatic and dendritic recordings in a hippocampal CA1 pyramidal neuron showing an isolated dendritic spike (top) and a dendritic spike preceding a somatic action potential (bottom). (D) Two-photon uncaging of glutamate onto the dendrites of a CA1 pyramidal neuron. Somatic recordings show a nonlinear increase in the somatic EPSP amplitude and slope, indicative of a dendritic spike that did not trigger an action potential in the axon or soma.

(A, B) Stuart et al., 1997a; (C) Golding and Spruston, 1998; (D) Losonczy and Magee, 2006.

Figure 11.7 Dendritic calcium spikes and NMDA spikes. (A) Simultaneous somatic and dendritic (920 μm from soma) recordings from a neocortical layer 5 pyramidal neuron. Synaptic stimulation in layer 2/3 (left traces) or current injection into the dendrite (right) resulted in a dendritic Ca2+ spike (subthreshold responses also shown) in the dendrites that did not propagate to the soma (soma, 440 μm and 770 μm from soma). (B) (a) Schematic of triple recording from a layer 5 pyramidal neuron. (b) Responses to EPSC-like dendritic current injection. (c) Responses to somatic current injection. (d) Responses to combined somatic and dendritic current injections. (e) Responses to larger dendritic current injection. (C) Dual recording 715 μm and 875 μm from the soma in a layer 5 pyramidal neuron. Synaptic stimulation in layer 1 yields dendritic spikes that are restricted to the distal dendritic recording location and blocked by the NMDA receptor antagonist APV.

(A) Schiller et al., 1997; (B) Larkum et al., 1999; (C) Larkum et al., 2009.

One consequence of the weakly excitable nature of dendritic trees is that dendritic spikes do not propagate reliably throughout them. Like the backpropagating action potential, the attenuation of forward propagating dendritic spikes depends both on the types of channels activated during the spike and on the branching of the dendritic tree. Because of the structure of branch points, however, forward propagation is even less reliable than backpropagation. The difference arises from the geometry of the dendritic tree. Consider a backpropagating action potential traveling from the main apical trunk into an oblique branch in a pyramidal neuron. The amount of current required to generate the action potential in the trunk is quite large because of the large size of this dendrite. The oblique branch is much smaller, so a small fraction of the charge in the trunk is able to depolarize the oblique branch to threshold, thus resulting in successful backpropagation through the branch point. If an action potential is generated in the oblique branch and propagates toward the apical trunk, however, the situation is very different. The amount of charge required to generate a dendritic spike in the oblique branch is small because of the small diameter of the dendrite. As this charge flows into the apical trunk, there is too little current to depolarize the trunk to threshold, so the dendritic spike fails at the branch point. The asymmetry of propagation through dendritic branches is caused by an impedance mismatch: the apical trunk has a low input impedance and the oblique branch has a high input impedance. It is relatively easy for a regenerative event such as an action potential or dendritic spike to propagate from a low-impedance to a high-impedance structure but relatively hard for propagation to occur from a high-impedance to a low-impedance structure.

Dendritically initiated spikes come in different varieties: Na+ spikes, Ca2+ spikes, and NMDA spikes (Figs. 11.6 and 11.7). These spikes are named for the dominant channel type activated during the spike, although in fact multiple types of channels are usually activated during each type of event. For example, even when a Na+ spike is observed, NMDA receptor activation might be critical for providing the depolarization that triggers it, and the resulting depolarization from the spike is usually large enough to activate Cav channels. The spike is still called a Na+ spike—typically identified as the fastest dendritic event (because of the fast kinetics of Nav channels)—but a significant increase in intracellular Ca2+ would be observed in a Ca2+ imaging experiment because of the activation of NMDA receptors and Cav channels.

The first dendritically initiated spikes to be described were dendritic Ca2+ spikes, which were observed in experiments performed in the 1970s and 1980s using sharp microelectrodes to record from the dendrites of Purkinje neurons and pyramidal neurons (Fig. 11.4). These spikes were initiated in response to strong excitatory synaptic inputs and were presumed to have a dendritic origin because of their large amplitude in dendritic recordings. Subsequent to these early experiments, the dendritic origin of these Ca2+ spikes was confirmed in simultaneous somatic and dendritic recordings using patch-clamp recording (Box 11.2). Ca2+ spikes have a long duration (relative to Na+ spikes), consistent with the slow kinetics of Cav channels compared to Nav channels. In some cases, dendritic Ca2+ spikes of especially long duration have been called “plateau potentials.” Although dendritic Ca2+ spikes were first observed only with strong synaptic stimulation, they have also been shown to occur in the apical tuft of pyramidal neurons when weaker synaptic excitation is paired with one or more backpropagating action potentials. These events have been called “backpropagating action potential evoked Ca2+ spikes” or “BAC spikes” (Fig. 11.7). They are of particular interest because they may signal the coincidence of synaptic input to the apical tuft and other dendritic domains of pyramidal neurons.

Dendritic Na+ spikes are fast events (compared to Ca2+ spikes), so they tend to be very localized and do not propagate reliably out of the branch in which they were generated (Fig. 11.6). This fact is likely responsible for the relatively late discovery of dendritic Na+ spikes, compared to Ca2+ spikes. Dendritic Na+ spikes were first definitively identified when it became possible to simultaneously monitor somatic and dendritic membrane potential using patch-clamp recording in brain slices. This technique allowed definitive identification of dendritic spikes that occurred either before or in the absence of a somatic action potential. At first, dendritic Na+ spikes were only observed in response to relatively strong stimulation of excitatory synapses. The strong stimulus used to evoke dendritic spikes suggested that they might only occur under conditions of extreme excitation, thus raising questions about their physiological significance. However, subsequent experiments using two-photon Ca2+ imaging and glutamate uncaging (Box 11.3), combined with somatic and dendritic recording, have indicated that dendritic spikes may occur in response to clustered activation of a small number of synapses on a single branch (i.e., less than ten synapses). Dendritic Na+ spikes are hard to detect, even with dendritic recording, because the spikes do not propagate reliably into the large-diameter dendrites from which dendritic recordings are typically obtained.

Dendritic NMDA spikes result from activation of NMDA receptor channels, which are voltage sensitive because of their block by Mg2+. When glutamate is bound to NMDA receptors, they can produce a regenerative event, as depolarization leads to relief of Mg2+ block, resulting in more inward current and more depolarization. If enough NMDA receptors are activated, a regenerative spike can occur, even if significant numbers of Nav and Cav channels are not activated. NMDA spikes have one important feature that is fundamentally different from Na+ or Ca2+ spikes. NMDA spikes cannot propagate into regions of the dendrite where NMDA receptors are not activated by glutamate (or where they are activated only in small numbers). As noted above, dendritic Na+ spikes also propagate poorly and typically remain restricted to the dendrite in which they were originated. Unlike NMDA spikes, however, dendritic Na+ spikes can propagate into regions of the branch where synapses have not been activated. NMDA spikes cannot propagate in this way because of the additional requirement that the receptor needs to be activated by glutamate before it can respond to depolarization.

Functions of Dendritic Spikes

An important question regarding excitable dendrites is to determine the functions of dendritic spikes and backpropagating action potentials. Two key issues are which of these events occurs in vivo, and under what conditions? Although good progress is being made to develop the methods necessary to address these questions, they remain unanswered. Thus, most of what we can say about the function of dendritic spikes stems from what we have learned about them from in vitro brain-slice experiments. Generally, the possible functions of backpropagating action potentials and dendritic spikes can be divided into three categories: a role in synaptic integration, a role in local communication, and a role in plasticity.

Dendritically initiated spikes are likely to play a central role in the process of synaptic integration, but understanding how this works is not straightforward. For example, if a dendritic Na+ spike does not propagate out of the dendritic branch in which it was generated, how can it influence action potential initiation in the axon? The most likely answer to this puzzling question is that the dendritic spike, although not propagating actively, does deliver additional charge to the axon, over and above the charge entering at synapses alone. In this way, dendritic excitability lowers the number of excitatory synapses required to initiate action potential firing in the axon. Thus, even though individual synapses in the distal dendrites minimally depolarize the axon (because of the dendritic filtering discussed above), the influence of distal synapses can be enhanced when they contribute to the generation of dendritically initiated spikes.

A leading theory in the field of dendritic integration is that dendritic spikes allow neurons to respond to coincident activation of multiple dendritic domains. For example, if Na+ spikes or NMDA spikes are generated in two oblique branches of pyramidal neurons, enough charge can be delivered to the axon to generate an action potential, even though the dendritic spikes do not actively propagate all the way to the axon. Another example is the BAC spike, discussed above; when coincident input occurs to the apical tuft and the basal dendrites of pyramidal neurons, a BAC spike can be generated in the tuft, leading to a burst of action potentials at the soma. Yet another example from pyramidal neurons is that spikes generated in the apical tuft normally fail at the branch point between the tuft and the main apical dendrite. When this critical region near the branch point is depolarized by other synaptic inputs, however, the tuft spike can propagate actively along the main apical trunk and trigger action potential firing in the axon. Thus, dendritic spikes may allow the neuron to detect the coincident activation of excitatory synaptic inputs to different dendritic compartments. A central question, then, which is the focus of much ongoing work, is what kinds of inputs, carrying which kinds of information, arrive in the different dendritic compartments of pyramidal neurons.

The concept of coincidence detection through dendritic excitability is not restricted to pyramidal neurons. Cerebellar Purkinje neurons can also detect the coincidence of inputs via the parallel fibers and the climbing fiber. Although climbing fibers on their own are sufficiently strong to reliably evoke dendritic Ca2+ spikes in Purkinje cells, coincident input via the parallel fibers can increase the number of Ca2+ spikes evoked by a single presynaptic action potential in the climbing fiber. Furthermore, the Purkinje cell dendritic tree branches so extensively that Ca2+ spikes can cause larger depolarizations in the vicinity of the activated parallel fibers than in other portions of the dendrites. One important outcome of the larger dendritic spikes associated with such coincident activity is the induction of long-term depression (LTD) of the activated parallel fibers.

The end result of coincidence detection is usually a dendritic spike. As an outcome of synaptic integration, a dendritic spike can enhance action potential firing in the axon. In the case of Ca2+ spikes (including BAC spikes), the result is often a burst of action potentials in the axon, which is likely to more powerfully promote the release of neurotransmitter from the axon terminals, compared to a single action potential. In Purkinje cells, however, the main function of the burst of action potentials may be the long pause in firing that follows the burst. Purkinje cells fire spontaneously and release the inhibitory transmitter GABA, so the pause in firing that follows the Ca2+ spike-induced burst may ultimately serve to activate the postsynaptic neurons in the deep cerebellar nucleus by releasing them from tonic inhibition.

A second possible function of dendritic excitability, besides promoting action potential firing in the axon, is to mediate neurotransmitter release from dendrites. The best-studied example of this is in the olfactory bulb, where reciprocal dendro-dendritic synapses are formed between mitral cells and granule cells. Both cell types have been shown to have excitable dendrites, which likely plays a key role in the activation of these synapses. Even in dendrites lacking structurally identifiable presynaptic specializations, dendrites can release substances that mediate local communication. For example, both pyramidal neurons and Purkinje cells have been shown to release endocannabinoids from their dendrites in response to dendritic depolarization. Events mediated by voltage-gated channels in dendrites (namely backpropagating action potentials and dendritic spikes) are likely to promote the release of these and other substances from dendrites. Notably, dendritic release may also be an outcome of the coincidence detection operations described above.

A third possible function of dendritic excitability is the induction or regulation of changes in synaptic strength such as Hebbian synaptic plasticity (Fig. 11.8). What kinds of dendritic events could provide the depolarization necessary for Hebbian plasticity? Backpropagating action potentials and dendritic spikes are both good candidates. For example, the backpropagating action potential has been proposed as an important signal for the induction of spike-timing-dependent synaptic potentiation and depression, because the activation of Cav channels (backpropagating action potential alone) and the relief of Mg2+ block of NMDA receptors (backpropagating action potential together with the binding of presynaptically released glutamate to the receptor) are sensitive to the relative timing of presynaptic and postsynaptic activation. Other forms of synaptic plasticity can occur in the absence of backpropagating action potentials. For example, dendritically initiated spikes have been shown to promote these forms of long-term potentiation (LTP) of excitatory synaptic strength even in the absence of axonal action potential firing. For some forms of plasticity, events mediated by dendritic excitability (backpropagating action potentials and dendritic spikes) are a requirement for the induction of synaptic plasticity. Therefore, these events are likely to serve as detectors of postsynaptic coincidence detection, thus mediating the property of synaptic cooperativity in LTP—that is, the requirement for multiple synaptic inputs to cooperate to produce the depolarization necessary for the induction of Hebbian LTP.

Figure 11.8 Dendritic excitability and synaptic plasticity. (A) Blocking backpropagating action potentials with dendritic application of TTX prevents the induction of LTP by pairing EPSPs with action potential firing. (a) CA1 pyramidal neuron filled with a Ca2+-sensitive dye showing approximate location of TTX application (circle), strategically positioned to block action potential backpropagation without blocking action potential firing in the soma or synaptic transmission at more distal dendritic locations. (b) Ca2+-sensitive fluorescence changes during pairing of EPSPs and action potentials (evoked by somatic current injection) in control (solid lines) and during application of TTX to the proximal dendrite (dashed lines). Number traces correspond to the locations of the numbered boxes in (a). Bottom trace is somatically recorded membrane potential during pairing. (c) Group data showing failure to induce LTP during dendritic TTX application, but not in the absence of TTX application. (B) Stronger stimulation can induce LTP in CA1 pyramidal neurons even when action potential backpropagation is blocked. (a) Paired somatic and dendritic recording during activation of presynaptic axons (no pairing with somatic current injection) and application of TTX to the soma and proximal dendrites to prevent action potential backpropagation from the axon. Synaptic stimulation is strong enough to evoke dendritic spikes, which are severely attenuated in the soma. (b) Theta-burst synaptic stimulation induces LTP, which is observed in both the soma and the dendrite. (c) Group data showing LTP induction in experiments with backpropagating action potentials blocked. (C) Pairing of EPSPs and backpropagating action potentials in neocortical layer 5 pyramidal neurons induces either LTP or LTD, depending on the amplitude of the backpropagating action potentials. In proximal dendrites, where backpropagating action potentials are relatively large, LTP is induced. In distal dendrites, where backpropagating action potentials are smaller, LTD is induced. Depolarization of the distal dendrite amplifies backpropagating action potentials, however, resulting in induction of LTP instead of LTD.

(A) Magee and Johnston, 1997; (B) Golding et al., 2002; (C) Sjöström and Häusser, 2006.

Although not as extensively studied, dendritic excitability may also contribute to other forms of plasticity, such as non-Hebbian synaptic plasticity, plasticity of inhibitory synapses, and plasticity of intrinsic membrane properties, including modulation of the very channels responsible for dendritic excitability. The latter mechanism could either work in a homeostatic manner or could enhance the probability of future dendritic spiking or synaptic plasticity. Finally, it should be noted that other processes might also regulate dendritic excitability. For example, modulatory neurotransmitters can regulate the activity of dendritic Nav, Cav, and Kv channels, thus changing the excitable properties of the dendrite. This positions dendritic excitability as a mechanism that is both a regulator and a target of various forms of plasticity.

Dendritic Inhibition and Dendritic Excitability

One of the great mysteries of synaptic integration is why there are so many different types of inhibitory interneurons. Using classification mechanisms that depend on morphology, axon projections, physiological properties, and molecular markers, a great diversity of inhibitory cell types has been described. For example, more than 20 different types of inhibitory interneurons have been described in the CA1 region of the hippocampus alone. Interestingly, more than half of these types of interneurons have axons that appear to innervate pyramidal neuron dendrites (Fig. 11.9A). What is the function of dendritic inhibition and why are the neurons that mediate it so diverse? At the moment, we have only limited insight into this problem, owing to the limited experimental data.

Figure 11.9 Functions of dendritic inhibition. (A) Compilation of inhibitory interneurons (dendrites blue, axon red) superimposed on a CA1 pyramidal neuron (black) to illustrate dendritic inhibition. (B) Effects of inhibition on backpropagating action potential in a CA1 pyramidal neuron. (C) Spikes evoked by current injection in a recording from a CA1 pyramidal neuron (top) are inhibited effectively by dendritic inhibition (middle), but not somatic inhibition (bottom). (D) (a) Simultaneous recording from a pyramidal neuron (red, soma and dendrite) and a neighboring inhibitory interneuron (blue). Scale bar is 200 μm. (b) BAC spike evoked by simultaneous somatic current injection to evoke an action potential and synaptic stimulation in layer 1 (somatic recording black; dendritic recording red). (c) BAC spike is blocked by activation of an action potential in the inhibitory interneuron (blue). IPSPs in the pyramidal neuron are also shown (i.e., with no current injection in pyramidal action potential or activation of layer 1 synapses).

(A) N. Spruston, McQuiston and Madison, 1999, Halasy et al., 1996; (B) Tsubokawa and Ross, 1996; (C) Miles et al., 1996; (D) Larkum et al., 1999.

One of the most obvious functions of dendritic inhibition would be to selectively reduce the impact of excitatory synaptic inputs in the same dendritic compartment. For example, an interneuron that innervated the apical tuft of a pyramidal neuron might powerfully inhibit excitatory inputs to the tuft, while having little or no effect on excitatory synapses on basal dendrites. That said, the excitatory inputs that are affected by dendritic inhibition need not overlap directly with the inhibitory inputs. As noted above, for inhibition to be most effective, it should be on the path from the site of excitatory synapses to the axon.

Another likely function of dendritic inhibition is to regulate events mediated by dendritic excitability, such as backpropagating action potentials and dendritic spikes. Indeed, there is experimental evidence that these events can be attenuated by dendritic inhibition (Fig. 11.9B and 11.9C). Understanding the roles of different types of interneurons in this process is complex, however, because different varieties of dendritic spikes can be initiated in different dendritic compartments. To fully appreciate the role of dendritic inhibition, it will be necessary to understand not only the postsynaptic actions of each type of interneuron but also to understand when and why each interneuron type is active. For example, one study showed that feedback inhibition from one type of interneuron targets the proximal apical dendrites. During sustained firing, this form of dendritic inhibition outlasted somatic inhibition provided by a different type of interneuron. This cell-type-specific form of inhibition results from a combination of the intrinsic and synaptic properties of each type of interneuron. The ultimate goal is to understand when and why each cell type is activated in the intact brain and how this activity affects circuit function to mediate behavior and cognition.

Structure and Function of Dendritic Spines

The dendrites of many neurons are covered with thousands of dendritic spines—small protuberances that form the primary sites of contact for excitatory synapses (and some inhibitory synapses) in many types of neurons. Ever since their discovery by Ramon y Cajal, the function of spines has been a mystery. Today, we know a great deal more about the electrical and chemical properties of spines, but the reason for their existence remains elusive. We know for sure that dendritic spines are not essential for the basic function of excitatory synapses, since many neurons—most notably inhibitory interneurons—receive excitatory synapses directly onto their dendrites and lack dendritic spines. Even in some spiny neurons, some excitatory synapses are formed directly onto the dendrite, raising the possibility that excitatory synapses on spines and dendrites may have distinct functional properties. Certainly, the abundance of spines in the nervous system suggests strongly that they serve an important function.

Structure of Dendritic Spines

The typical dendritic spine is often described as having a “mushroom” shape, consisting of a narrow spine neck and a larger spine head (about one micron diameter). However, the structure of dendritic spines can be quite varied, even for spines on a single neuron (Fig. 11.10). Some spines have particularly long necks, which tends to correlate with smaller spine heads, while other spines have short, stubby necks and an unclear distinction between the neck and the head. In electron micrographs, spines are characterized by the presence of smooth endoplasmic reticulum and an actin cytoskeleton, as well as by the absence of microtubules, ribosomes, and mitochondria. In some cases a particularly extensive endoplasmic reticulum forms a structure called a “spine apparatus.” One of the most distinctive features of dendritic spines is the postsynaptic density (PSD), which is an electron-dense region opposite the presynaptic terminal, thought to contain the postsynaptic machinery for synaptic function. Typically, PSDs are largest in mushroom-shaped spines and smaller in thin or stubby spines. As noted above, some spines have particularly large PSDs that are interrupted by a perforation. Strong correlations have been noted among the size of the spine head, the size of the PSD, and the number of AMPA-type glutamate receptors, indicating that there is a relationship between spine size and synaptic strength.

Figure 11.10 Spine diversity. (A) Dendritic spines expressing GFP-tagged actin (green) decorate a MAP2-labeled dendrite (red) of a cultured hippocampal neuron. Scale bar is 5 μm. (B) Dendritic spines at increasing magnification from: (a) neocortical pyramidal neuron, (b) hippocampal CA1 pyramidal neuron, (c) neocortical pyramidal neuron, (d) cerebellar Purkinje cell, (e) CA1 pyramidal neuron showing mushroom (M) and thin (t) pedunculated spines. (a–d) are light microscopy and (e) is an EM reconstruction. (C) Cartoons of different spine shapes. (D) Cartoons of small and large axo-spinous synapses. Note the “perforation” of the PSD in the large synapse. In CA1 pyramidal neurons, approximately 20% of synapses have perforated PSDs. These PSDs also have a higher density of AMPA receptors than nonperforated PSDs, suggesting that they are especially powerful synapses. (E) Cartoon illustrating the most abundant organelles and molecules in spines, including: smooth endoplasmic reticulum (SER), coated vesicles (CV), F-actin, and numerous other molecules associated with the postsynaptic density (PSD).

(A) Matus, 2000; (B) Fiala et al., 2008; (C) Hering and Sheng, 2001; (D) Geinisman, 2000; (E) Hering and Sheng, 2001.

It has been suggested, and recently confirmed by experimental observations, that structural changes in dendritic spines can occur together with synaptic plasticity. This is a seemingly simple idea—stronger synapses need bigger spines, so growth of the spine is required for synaptic potentiation (e.g., LTP)—but complexities and open questions lurk beneath the surface of this idea. Can changes in spine structure alone mediate changes in synaptic strength, or are other molecular changes required as well? Are thin spines the initial precursors of mushroom spines and stubby spines the remnants of retracting spines, or does spine diversity reflect a diverse population of stable synapses? Indeed, conversion between the different types of spines has been observed in vitro and in vivo. A consensus from the in vivo studies is that some spines change over time, while other spines are extremely stable, reflecting the need for a balance between plasticity and stability in neural circuits.

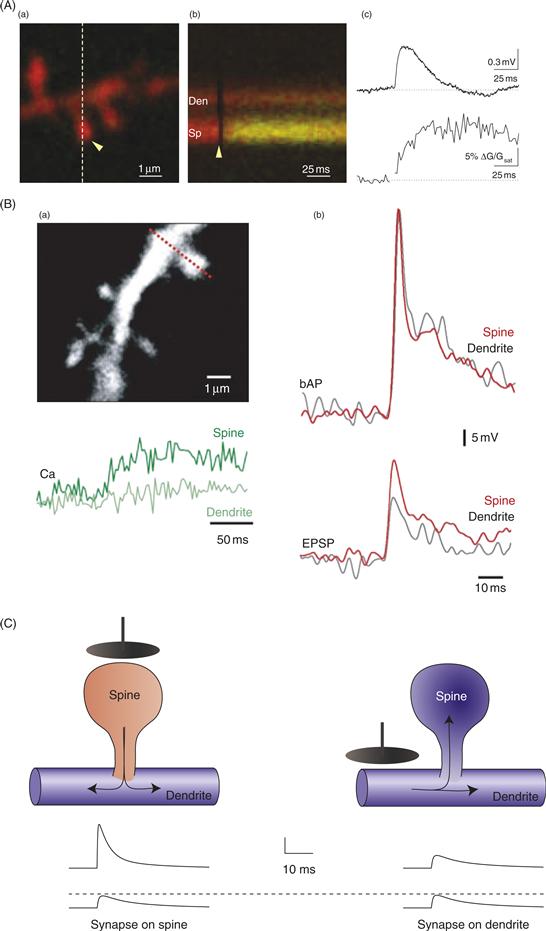

Chemical and Electrical Compartmentalization in Spines