This chapter shows you how to take stock of your inner resource or your Self and the Supports that surround you.

We all bring many personal resources to our transitions. Some of these, like financial assets, are tangible. Others, like personality or outlook, are less obvious but just as important.

What do you bring of your Self to the many transitions you face? When you try to answer that question, you get into the interesting but challenging task of defining who you are. We have all heard people say, “You would really like Jane. She has a wonderful personality.” What does that mean? Does it mean that Jane has traits that are considered “good” in our culture or group? Does it mean that Jane handles life with ease? Does it mean that she has a way of looking at things that makes her a pleasure to be with? These questions show that the process of understanding ourselves and what we bring to a transition is a complex one. Yet, we all know that a persons behavior and outlook are very critical to managing change.

Since we cannot touch or see someone’s inner resources, we will examine one individual, Steve, to illustrate how he TAKES STOCK of his inner resources.

Steve had a good income, enjoyed good health, and had many friends. He was married to his college sweetheart. He felt “on top of the world.” But that world shattered when Steve and his vice president had a falling out over the direction the company should take. After a long political struggle, Steve was asked to resign. He felt crushed. At fifty-eight, he felt too old to go looking for another job and too young not to work. Soon after, his wife died of a heart attack. Steve had to face two potentially devastating transitions, which exaggerated his fears of aging and loneliness. Over time, he found a job in a nonprofit organization. He met new people and developed some very close relationships. Many of Steve’s friends attribute his eventual triumph to his inner strengths and resources.

Some would say that Steve has a “hardy personality”; others would point to Steve’s wisdom, perspective, and humor; many might point to his resilience and flexibility, which are invaluable in enabling someone to bounce back and change course.

Resilience is clearly a dominant theme in psychological literature. George Vaillant wrote, “Resilience reflects individuals who metaphorically resemble a twig with a fresh, green living core. When twisted out of shape, such a twig bends, but it does not break; instead, it springs back and continues growing.”1 Steve bent but did not break. Psychologist Salvatore Maddi studies the relationship between resilience and hardiness. He wrote, “There are multiple pathways to resilience under stress . . . and . . . hardiness” is one.2 Specifically, hardiness is an attitude that “helps in transforming stressors from potential disasters into growth opportunities,” thereby promoting resiliency. According to Maddi, a hardy individual is someone who exhibits certain attitudes or approaches to life. First, the individual is involved and committed, feels in control of outcomes, and is challenged by negative occurrences. By contrast, a person who distances from others, feels passive in the face of challenges, and avoids facing the issue does not exhibit hardy behavior and therefore will be less resilient.

Maddi and his team studied the Illinois Bell Telephone (IBT) company over a period of ten years after the workforce had been dramatically and drastically reduced. Some of the managers crumbled under the stress while others embraced it and moved on. The latter showed commitment, control, and challenge.

Psychologist Shelley Taylor identified five different ways people responded to a diagnosis of breast cancer.3 “Fighting-spirits”—those with the will to fight, struggle, and resist—and “deniers”—those who refused to recognize the reality of the situation—had less recurrence of the disease. The other three types—the “stoics,” who submitted without complaint to unavoidable life circumstances; the “helpless persons,” who felt unable to cope without the help of others; and the “magical thinkers,” who believed that help would come through mysterious and unexplained powers—all had higher recurrence rates.

Another way to take stock of your Self and your inner resources is by identifying the degree to which you feel good about yourself—what psychologists Grace Baruch and Rosalind Barnett and writer Caryl Rivers have called a sense of “well-being.”4 They studied three hundred women to determine the factors contributing to well-being. Some of the women they studied had never married, others were married without children, some were married with children, and others were divorced with children. The authors found that those who put energy into several areas of their lives, such as work and family, were more satisfied than those who put all their eggs into only one basket, such as work or family. The authors concluded that investing in several aspects of life leads to a combination of mastery, pleasure, and a sense of well-being.

In the case of Steve, we can assume that he was overwhelmed at first because his sense of well-being had been totally disrupted. His balance of mastery and pleasure was shaken. But because of who he is, Steve was able to take on this challenge and once again gain control and balance in his personal and work life.

Many in transition feel helpless. A partner leaves you, your plant closes, birthdays keep accumulating, you choose to move to a new city. Many people experience these events as overwhelming. Are you the kind of person who usually gives up? Or do you meet the challenge head-on and try to take control?

We have discussed how Martin Seligman’s work focused on different ways people react, especially to negative, uncontrollable, or bad events. According to Seligman, those who feel they have control over their lives, or who feel optimistic about their own power to control at least some portions of their lives, tend to experience less depression and achieve more at school or work; they are even in better health. Seligman suggested that the individual’s “explanatory style”—the way a person thinks about the event or transition—can explain how some people weather transitions without becoming depressed or giving up. Since many transitions are neither “bad” nor “good” but a mixture, a persons “explanatory style” becomes the critical key to coping. A person with a positive explanatory style is an optimist, while one with a negative style is basically a pessimist.5

For example, we can ask how Steve explained what happened to him. Did he blame himself and say he lost out on the job because he was inadequate? Did he conclude that he would always be inadequate at work? People who blame themselves for everything that happens and then generalize to think they always “screw things up” have a good chance of being depressed and passive. On the other hand, Steve saw that he clearly had some role in the job decision and that, in general, he handles complex situations well; he thus had a good chance of coming out on top in a transitional situation.

Steve’s success in managing and weathering his transition suggests that he is probably an optimist and that his “explanatory style” is positive. Peterson and Seligman suggested that a persons explanatory style can predict success on a job. In a study of insurance salespersons, those representatives with a “positive explanatory style” were twice as likely as those with a “negative style” to still be on the job after a year. Following up on this study, a special force of a hundred representatives who had failed the insurance industry test but who had a “positive explanatory style” were hired. They were much more successful than the pessimists.6

Another way to TAKE STOCK of personal resources is to use personality tests such as the Myers-Briggs Type Indicator. This test, developed by Isabel Myers and Kathryn Briggs, is based on Jung’s descriptions of different “personality types.” This easy-to-score, easy-to-take personality test gives people an indication of how they habitually view life and its problems and shows how they make decisions about how to handle them.7

Some of us navigate through life by using intuition, and others navigate by using senses, like eyes and ears, to uncover the facts in a realistic way. Some people make decisions in a logical, systematic way; others do so by feeling what seems right. People can be differentiated along these dimensions. It may be helpful for you to try to determine how you and your family or acquaintances tend to function based on these criteria. Recognizing that your type might be different from that of your partner, boss, or friend may help you understand, for example, why you work well with one colleague and conflict with another. It could be a simple matter of different ways of understanding and approaching the world. Acknowledging these differences can be helpful in building collaboration rather than conflict.

I have used words like stress, transition, and coping. These words are used by psychologists in many different ways. Some define stress as an outside stimulus; others define it as a response to a stimulus. Others, like Lazarus and Folkman, define stress as a “particular relationship between the person and the environment that is appraised by the person as taxing or exceeding his or her resources and endangering his or her well-being.”8 Others who face major transitions—those that change many roles, routines, relationships, and assumptions—as Steve did may be challenged by them. Steve, who faced a very stressful set of transitions, was nevertheless challenged rather than overwhelmed. It is the interaction of the Situation and one’s Self that explains reactions to transition.

Regardless of whether these are innate or learned qualities, it is my conviction that all of us can increase the number of our coping strategies, thereby becoming more flexible and resilient. As we will see in chapter 5, the person who uses many strategies flexibly is the one who masters change. I believe we can learn how to increase our coping repertoire and build on what we already have.

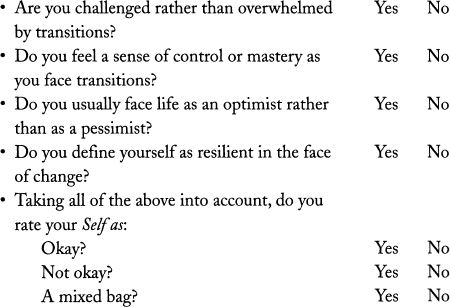

To summarize: To TAKE STOCK of your Self and your inner resources, you can ask yourself some questions:

Steve, who had lost both his job and his wife in a short period of time, needed a great deal of support despite his optimism and resilience. His friends were sympathetic and made the appropriate number of visits and phone calls. But they did not realize that the loss of support and intimacy, coupled with his fear of diminishing options because of his sex and age, made him feel that he had lost everything that had given meaning to his life.

Steve did not want to burden his friends, but he also knew he needed some extra support. Being creative, he visited his local church and joined a group called “Out of Work: Working it Out.” He built in a temporary support system without unduly burdening his friends.

Pat’s transition began when her good friend had a stroke at the age of forty. Pat thought, “If my friend is incapacitated, it could happen to me or my husband. If something happened to my husband, I am not prepared to support my family of six children.” Around the same time, Pat’s interest was piqued by a newspaper ad for a women’s external degree program. Since the program required only occasional weekends on campus, she began to think that it might be possible for her to complete the degree she had begun years ago and to prepare herself to be self-supporting. Pat’s husband, Bob, was very supportive when they initially discussed the idea of her returning to school. But when Pat was gone for three days at a time every six weeks Bob complained and even ridiculed her. Pat was so determined to complete the degree that she asked her mother to move in during the times she was away. The support of her mother and of the program made up for her husband’s negative behavior.

We see that even when people are in fairly stable relationships, we cannot assume a totally supportive situation. In interviews about support, I now ask, “In what ways is X supportive of you or your activities? In what ways could X be more supportive?” It seems that support is often a double-edged sword. In many instances support is given in exchange for some measure of control. The unwritten statement is “I’ll support you, but you need to behave as I think you should.”

Some people give support but in a way that is not helpful. One woman wrote, “My boyfriend of five years told me he was one step away from being in love with another woman. This called into question my past assumptions about our relationship. I began to doubt myself.” When I asked what helped her cope, she said, “professional counseling.” When asked if she had tried methods that were unhelpful, she replied, “Simply talking with friends. They could not understand—they were too biased. Their reactions ranged from pity for me to total anger. Although my friends meant well, they were ineffective.” This is a case where friends did not give the kind of support she needed.

Support is a very general concept. As a way to get a handle on it, I will describe what it is, where it comes from, and then show you how to visualize your own Support as you move through, tackle, face, or master your transitions.

We all have a visceral sense of what the word support means, of what we seek from friends, relatives, church, neighbors, coworkers, or even strangers. But understanding the functions of support—why it is important to us—is a bit more complicated.

Support systems help individuals mobilize their resources by sharing “tasks,” providing “extra supplies of money, materials, tools, skills,” and giving guidance about ways to improve coping. Psychologists Robert Kahn and Toni Antonucci identified the following functions of support:9

People receive affection, affirmation, and aid in many ways, from many sources. Sometimes they receive support from friends, but in other instances it comes from a professional. People can potentially get support from many sources: intimates, families, friends, strangers, and institutions. You, the person in transition, need to evaluate what kind of support you need—affection, affirmation, aid—and from what source you could receive it—friend, partner, stranger, or institution. Do you need support from one constant source, or would it help to have the comfort of a group of people who face similar problems? Today many people join self-help groups where they both give and receive support.

We often extol the virtues of an intimate relationship, but sometimes the person with whom we are most intimate cannot be our best support. The men whose jobs were eliminated, for example, resisted going to their wives, mostly because they felt guilty about inflicting this transition on their families. In one extreme case, a man actually dressed and pretended to go to work. His wife didn’t discover this until the unemployment checks began to arrive.

Despite these examples, most research confirms the importance of having an intimate—someone with whom you can share honestly and openly your inner world. Intimates are extremely important during transitions. Intimate support comes in several packages: the intimacy you can achieve with friends who are often part of your adult life; the intimacy you can achieve with your spouse or partner; and the more permanent intimacy you receive from parents, siblings, and children.

Family can be a key source for giving and receiving affection, affirmation, assistance—and, at times, honest feedback. In most of our lives, the “forever” relationships are intergenerational, between grandparents, parents, and children. Without wanting to glorify these relationships (because they, like all others, are fraught with ambivalence and stress as well as support), we realize that they are central to our feelings of well-being. As we live longer, an increasing number of us continue to be part of four-or five-generation families. Sociologist Gunhild Hagestad, a demographer and researcher specializing in families and aging, observed, “These family patterns, unprecedented in human history, have in a way taken our society by surprise. . . . Families today may have to sort out who gives help and support to whom when two generations face aging problems.”10 One woman about to retire felt obligated to have her mother move in with her when her mother became ill and depressed. The daughter was not happy about the prospect of spending her retirement years with her mother, since there had always been friction between them. But she realized that although she might be aggravated, she wasn’t lonely. Most studies show that adult children stay in touch with their aging parents and that family members constitute the greatest sources of assistance to one another.

Support from friends, lovers, and partners also helps buffer stress, but the type of support they provide may differ from that provided by the family. Lillian Rubin found in her study of friendships that “friends help in the lifelong process of self-development, often becoming . . . people who join us in the journey toward maturity, who facilitate our separation from the family and encourage our developing individuality.”

Thus, she points out, “One of the most valued gifts friends offer us [is]—a reflection of the self we most want to be. In the family it’s different. There, it’s our former selves that are entrenched in both the family’s vision and our own.” Rubin points to the changing functions and roles of friends and asserts that it is important to have a number of different types of intimates. She had found from countless interviews that “even when people are comfortably and happily married, the absence of friends exacts a heavy cost in loneliness and isolation.”11

When Rodney, a community organizer, found he had cancer, he fought it with all the energy he could muster. He went to the best doctors and even became part of a research experiment, but he went through physical and mental agony. His wife and adult children were totally supportive, and he also benefited from the support of a set of very close friends who had known the family since college days.

At the time of his diagnosis, Rodney was negotiating a major grant from a foundation. When the foundation learned that he had cancer, the negotiations fell apart. The feeling that he would now have to face a financial crisis on top of a life-threatening disease devastated Rodney. He explained the situation to his doctor, a relative stranger, who wrote a letter to the foundation explaining the circumstances of Rodney’s disease and suggesting that the foundation would be guilty of discrimination if it did not provide the funds. As a result of the letter, the foundations decision was reversed and Rodney received the grant. This case illustrates the necessity of having access to a variety of types of support—support from intimates, from friends, and from strangers.

A professional woman who lives in Washington, DC, went to Denver to make a speech. When she arrived at the hotel where the meeting was scheduled, she learned that she arrived one month early. Unable to comprehend that she had done this, she was momentarily very upset. To compensate, she decided to treat herself to a lovely lunch at one of the best restaurants in town. The maitre d’ was friendly, and the woman found herself telling him about her terrible error. He laughed and told her about a mistake he had made. This interchange with a stranger was enormously helpful, and by the time lunch was over, she had regained her humor and perspective.

One woman described how she coped with widowhood: “The transition was unanticipated and outside my control, so there was a high degree of stress. This was balanced by an environment of tremendous social support from family, friends, and my department at work. I could not have survived without the constant telephone calls, concern, and continuous offers of help. I was surprised at my initiative in creating a support group of single women to share common concerns.”

Many people do not have the energy to create a new ad hoc support group. Fortunately, many existing organizations are already available to support us in times of change. There are many single-purpose organizations such as Alcoholics Anonymous (AA), where alcoholics offer advice and strength to others. The idea behind AA has been expanded to other special-purpose organizations, such as Gamblers Anonymous, Overeaters Anonymous, and many more such groups.

Other single-purpose groups have sprung up. These include Parents Without Partners, caregivers of those with Alzheimer’s disease, and parents of disabled children, including those with learning disabilities, mental illness, and physical illness.

More general are institutions such as Family Services, Red Cross, Travelers Aid, and the various social welfare and counseling arms of religious, ethnic, and national groups.

Then, of course, there are a host of organizations created to deal with special groups: women, Hispanics, blacks, immigrants, the foreign-born, homosexuals, and other groups that have not been getting their share of support from society.

In addition, there are organizations such as unions, professional business, trade groups, and churches that offer formal services in addition to the tremendous resource of the “people power” of fellow congregants, who can and do become helpers at least and friends at best.

Whether you are facing a troubling situation or initiating a desired change, the support you receive from institutions can be invaluable.

The support networks and intimate relationships available to us depend on many factors—where we live, our age, our economic status, our own personality. But some research suggests that sex is a particularly important determinant of the composition of ones support. Men and women live in somewhat different worlds—one major difference stems from the changing sex ratio over the course of life. Although more boys are born than girls, by the time people are in their mid-thirties, there are more women than men. This imbalance has resulted in remarriage becoming a disproportionately male experience after age forty. By the time people are in their eighties, there are more than twice as many women as men. Thus, the majority of older women are widowed and have a social life with other women, while most older men are married and have a social life with couples.

A landmark UCLA study found that women respond differently to stress than men. Furthermore, their bonds with other women are long lasting and serve as buffers to stress. Friends clearly help people live longer by lowering blood pressure, heart rate, even cholesterol. Women are the ones that connect and maintain relationships with other women, making women’s friendships special.12

The types of Supports we need and can offer may change depending on our age and circumstances. The demographics of age and sex may impinge on our ability to get the type of Supports we need at the time we need them. Hagestad’s interviews with grandparents, middle-aged men, and women and their adult children suggest that mens ups and downs are tied more often to the world of work and politics, while women’s are related more to events in the family. Furthermore, she found that when men get together, they talk about work, education, money, and social issues, while women focus more on interpersonal relations and family.13

Often we forget that a person who is giving support to a friend or family member may also require some support to help shoulder the additional burden. We can see this in the case of Mark, whose sister Sarah confided that she was having her second abortion and swore him to secrecy. Mark became Sarah’s rock through the trauma, although it was extremely difficult for him since his political and philosophical views about the morality of abortion were in flux at the time of Sarah’s confidence. Because Mark loved Sarah, he stuck by her and didn’t tell her about his own changing views. In addition, he couldn’t confide in any of his friends about the stress of being Sarah’s supporter because this was Sarah’s secret. Mark was helping Sarah to cope, but he needed support so that he could continue being her supporter.

Another example is Adele, a woman whose best friends baby died. Adele’s role was coordinating the funeral and friends’ visits. She reported that she had no time to mourn the loss herself and felt stressed by her coordinating role. She, too, felt a need for tender loving care.

Because life is by definition a series of transitions for all of us, the specific individuals with whom we have supportive relationships change as life unfolds, and the options for relationships also change. We also require different types of support at different times.

Kahn and Antonucci have developed a way for you to identify your potential Supports by drawing a series of concentric circles with you at the center (see figure 4–1). The circle closest to you contains your closest, most intimate friends and family, who are presumably part of your life forever. The next circle is for family, friends, and neighbors who are important in your life but not in the intimate way the first group is. The circle farthest away from you represents institutional supports. Kahn and Antonucci call these circles an individuals “convoy of social support,” which are carried through life.14

FIGURE 4.1. YOUR “CONVOY OF SOCIAL SUPPORT”

Source: Based on work from R. L. Kahn and T. C. Antonucci, “Convoys over the Life Course: Attachment, Roles, and Social Support,” in Life-Span Development and Behavior, edited by P. B. Baltes and O. C. Brim, Jr. (New York: Academic Press, 1980), 273. Reprinted by permission.

Transitions shift one’s supports. By mapping out your Supports in concentric circles you can visualize how your transition alters your support system. For example, geographical moves can interrupt relationships between husbands and wives. Spouses who do not want to move but do so for the sake of the family may harbor deep resentment and anger. Thus, a wife who follows her husband may have had him in the center of her life before the move, but she may shift him to one of the more distant circles after it. In a contrasting case, a new college administrator reported that his wife was delighted with their move back to Washington, DC, because she lived there when she was younger and therefore has a large support network. If we were to compare her concentric circles before and after the move, her husbands place would be the same—in the closest circle.

Other examples can be readily found by looking at what happens to people’s support systems before and after retirement. If a newly retired couple moves away from many Supports to a place with none, the transition may be very difficult. If, however, retirement liberates one of the spouses to move back to an area where there are intimate relatives and friends, then it might be a much easier transition. This system of concentric circles shows that the most important aspect of a transition may not be the change itself but what it does to the individual’s “convoy.”

To take stock of your Supports you can ask yourself:

David, a top administrator in the state highway patrol, returned to school to earn a degree that would enable him to become a teacher when he retired. Full of enthusiasm, he enrolled in a state university. To all appearances David was a responsible, dedicated professional who had identified teaching as a means of making the transition to a second career in his retirement years. Yet, two years and a lot of hard work later, he dropped out of school without finishing the requirements for the degree. “I feel disappointment, some resentment, and at times anger,” he said after the experience. “I usually achieve what I start out to achieve.”

What went wrong? David thought he had accumulated enough credits to graduate by taking courses at the university and by enrolling in a program designed to evaluate prior experience and, if appropriate, award credit. The process of applying for such credit is complicated and requires the learner to develop a detailed portfolio of each experience. David applied for his B.A. degree, only to discover that although he had enough credits, many were from community college courses, and he did not have enough from the university. When he realized that he still needed sixty more credits that had to be taken on the campus, David became infuriated and dropped out of school.

In order to understand what happened, let’s TAKE STOCK of David’s Situation, Self, and Supports. In the next chapter we can TAKE STOCK of his Strategies.

There were many pluses in David’s Situation. The transition was one he had elected, and he was beginning to see himself as someone who could make his career dreams come true. However, his Situation had some negatives. For example, his changed routines required that he drive ninety miles each way twice a week. He had to plan carefully so that, in addition to the drive, he could find time to study as well as work and spend quality time with his family. David felt that his family was getting the short end of the stick. But, despite the negatives, he was pleased about the transition to learner and evaluated it positively.

David described himself as a “hard worker,” a “go-getter.” He classified himself as a “fighting spirit” and an “optimist,” but he added, “If things don’t go the way I think they should, I can fly off the handle. Maybe I am a little short on patience.” So David may be his own best and worst resource. He fights for what he wants and believes in, but he may give up if the odds seem unfavorable.

David assessed his family support as “terrific.” His wife took on additional family responsibilities so that he could give his all to getting his degree. He also felt positively about his coworkers’ support. Some teased him about going to school, but mostly they thought it was great. He was getting a good supply of affection, affirmation, and aid.

David’s downfall was his perceived lack of institutional support. He claimed he never received information about the credit limitations from outside institutions. The dean claimed that David was informed but was so eager that he didn’t pay attention to advice to slow down. Whatever the facts, there was clearly a breakdown in communication—a breakdown that prompted David to leave.

When we TAKE STOCK of his Situation, Self, and Supports two crucial insights emerge: