As we've mentioned, firewalls are a very effective type of network security. This section briefly describes what Internet firewalls can do for your overall site security. Section 5.1 and Chapter 7 define the firewall terms used in this book and describe the various types of firewalls in use today, and the other chapters in Part II and those in Part III describe the details of building those firewalls.

In building construction, a firewall is designed to keep a fire from spreading from one part of the building to another. In theory, an Internet firewall serves a similar purpose: it prevents the dangers of the Internet from spreading to your internal network. In practice, an Internet firewall is more like a moat of a medieval castle than a firewall in a modern building. It serves multiple purposes:

It restricts people to entering at a carefully controlled point.

It prevents attackers from getting close to your other defenses.

It restricts people to leaving at a carefully controlled point.

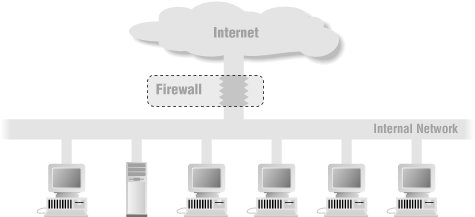

An Internet firewall is most often installed at the point where your protected internal network connects to the Internet, as shown in Figure 1.1.

All traffic coming from the Internet or going out from your internal network passes through the firewall. Because the traffic passes through it, the firewall has the opportunity to make sure that this traffic is acceptable.

What does "acceptable" mean to the firewall? It means that whatever is being done—email, file transfers, remote logins, or any kinds of specific interactions between specific systems — conforms to the security policy of the site. Security policies are different for every site; some are highly restrictive and others fairly open, as we'll discuss in Chapter 25.

Logically, a firewall is a separator, a restricter, an analyzer. The physical implementation of the firewall varies from site to site. Most often, a firewall is a set of hardware components — a router, a host computer, or some combination of routers, computers, and networks with appropriate software. There are various ways to configure this equipment; the configuration will depend upon a site's particular security policy, budget, and overall operations.

A firewall is very rarely a single physical object, although some commercial products attempt to put everything into the same box. Usually, a firewall has multiple parts, and some of these parts may do other tasks besides function as part of the firewall. Your Internet connection is almost always part of your firewall. Even if you have a firewall in a box, it isn't going to be neatly separable from the rest of your site; it's not something you can just drop in.

We've compared a firewall to the moat of a medieval castle, and like a moat, a firewall is not invulnerable. It doesn't protect against people who are already inside; it works best if coupled with internal defenses; and, even if you stock it with alligators, people sometimes manage to swim across. A firewall is also not without its drawbacks; building one requires significant expense and effort, and the restrictions it places on insiders can be a major annoyance.

Given the limitations and drawbacks of firewalls, why would anybody bother to install one? Because a firewall is the most effective way to connect a network to the Internet and still protect that network. The Internet presents marvelous opportunities. Millions of people are out there exchanging information. The benefits are obvious: the chances for publicity, customer service, and information gathering. The popularity of the information superhighway is increasing everybody's desire to get out there. The risks should also be obvious: any time you get millions of people together, you get crime; it's true in a city, and it's true on the Internet. Any superhighway is fun only while you're in a car. If you have to live or work by the highway, it's loud, smelly, and dangerous.

How can you benefit from the good parts of the Internet without being overwhelmed by the bad? Just as you'd like to drive on a highway without suffering the nasty effects of putting a freeway off-ramp into your living room, you need to carefully control the contact that your network has to the Internet. A firewall is a tool for doing that, and in most situations, it's the single most effective tool for doing that.

There are other uses of firewalls. For example, they can be used to divide parts of a site from each other when these parts have distinct security needs (and we'll discuss these uses in passing, as appropriate). The focus of this book, however, is on firewalls as they're used between a site and the Internet.

Firewalls offer significant benefits, but they can't solve every security problem. The following sections briefly summarize what firewalls can and cannot do to protect your systems and your data.

Firewalls can do a lot for your site's security. In fact, some advantages of using firewalls extend even beyond security, as described in the sections that follow.

Think of a firewall as a choke point. All traffic in and out must pass through this single, narrow choke point. A firewall gives you an enormous amount of leverage for network security because it lets you concentrate your security measures on this choke point: the point where your network connects to the Internet.

Focusing your security in this way is far more efficient than spreading security decisions and technologies around, trying to cover all the bases in a piecemeal fashion. Although firewalls can cost tens of thousands of dollars to implement, most sites find that concentrating the most effective security hardware and software at the firewall is less expensive and more effective than other security measures — and certainly less expensive than having inadequate security.

Many of the services that people want from the Internet are inherently insecure. The firewall is the traffic cop for these services. It enforces the site's security policy, allowing only "approved" services to pass through and those only within the rules set up for them.

For example, one site's management may decide that certain services are simply too risky to be used across the firewall, no matter what system tries to run them or what user wants them. The firewall will keep potentially dangerous services strictly inside the firewall. (There, they can still be used for insiders to attack each other, but that's outside of the firewall's control.) Another site might decide that only one internal system can communicate with the outside world. Still another site might decide to allow access from all systems of a certain type, or belonging to a certain group. The variations in site security policies are endless.

A firewall may be called upon to help enforce more complicated policies. For example, perhaps only certain systems within the firewall are allowed to transfer files to and from the Internet; by using other mechanisms to control which users have access to those systems, you can control which users have these capabilities. Depending on the technologies you choose to implement your firewall, a firewall may have a greater or lesser ability to enforce such policies.

Because all traffic passes through the firewall, the firewall provides a good place to collect information about system and network use — and misuse. As a single point of access, the firewall can record what occurs between the protected network and the external network.

Although this point is most relevant to the use of internal firewalls, which we describe in Chapter 6, it's worth mentioning here. Sometimes, a firewall will be used to keep one section of your site's network separate from another section. By doing this, you keep problems that impact one section from spreading through the entire network. In some cases, you'll do this because one section of your network may be more trusted than another; in other cases, because one section is more sensitive than another. Whatever the reason, the existence of the firewall limits the damage that a network security problem can do to the overall network.

Firewalls offer excellent protection against network threats, but they aren't a complete security solution. Certain threats are outside the control of the firewall. You need to figure out other ways to protect against these threats by incorporating physical security, host security, and user education into your overall security plan. Some of the weaknesses of firewalls are discussed in the sections that follow.

A firewall might keep a system user from being able to send proprietary information out of an organization over a network connection; so would simply not having a network connection. But that same user could copy the data onto disk, tape, or paper and carry it out of the building in his or her briefcase.

If the attacker is already inside the firewall — if the fox is inside the henhouse — a firewall can do virtually nothing for you. Inside users can steal data, damage hardware and software, and subtly modify programs without ever coming near the firewall. Insider threats require internal security measures, such as host security and user education. Such topics are beyond the scope of this book.

A firewall can effectively control the traffic that passes through it; however, there is nothing a firewall can do about traffic that doesn't pass through it. For example, what if the site allows dial-in access to internal systems behind the firewall? The firewall has absolutely no way of preventing an intruder from getting in through such a modem.

Sometimes, technically expert users or system administrators set up their own "back doors" into the network (such as a dial-up modem connection), either temporarily or permanently, because they chafe at the restrictions that the firewall places upon them and their systems. The firewall can do nothing about this. It's really a people-management problem, not a technical problem.

A firewall is designed to protect against known threats. A well-designed one may also protect against some new threats. (For example, by denying any but a few trusted services, a firewall will prevent people from setting up new and insecure services.) However, no firewall can automatically defend against every new threat that arises. People continuously discover new ways to attack, using previously trustworthy services, or using attacks that simply hadn't occurred to anyone before. You can't set up a firewall once and expect it to protect you forever. (See Chapter 26 for advice on keeping your firewall up to date.)

Firewalls can't keep computer viruses out of a network. It's true that all firewalls scan incoming traffic to some degree, and some firewalls even offer virus protection. However, firewalls don't offer very good virus protection.

Detecting a virus in a random packet of data passing through a firewall is very difficult; it requires:

Recognizing that the packet is part of a program

Determining what the program should look like

Determining that a change in the program is because of a virus

Even the first of these is a challenge. Most firewalls are protecting machines of multiple types with different executable formats. A program may be a compiled executable or a script (e.g., a Unix shell script or a Microsoft batch file), and many machines support multiple, compiled executable types. Furthermore, most programs are packaged for transport and are often compressed as well. Packages being transferred via email or Usenet news will also have been encoded into ASCII in different ways.

For all of these reasons, users may end up bringing viruses behind the firewall, no matter how secure that firewall is. Even if you could do a perfect job of blocking viruses at the firewall, however, you still haven't addressed the virus problem. You've done nothing about the other sources of viruses: software downloaded from dial-up bulletin-board systems, software brought in on floppies from home or other sites, and even software that comes pre-infected from manufacturers are just as common as virus-infected software on the Internet. Whatever you do to address those threats will also address the problem of software transferred through the firewall.

The most practical way to address the virus problem is through host-based virus protection software, and user education concerning the dangers of viruses and precautions to take against them. Virus filtering on the firewall may be a useful adjunct to this sort of precaution, but it will never completely solve the problem.

Every firewall needs some amount of configuration. Every site is slightly different, and it's just not possible for a firewall to magically work correctly when you take it out of the box. Correct configuration is absolutely essential. A misconfigured firewall may be providing only the illusion of security. There's nothing wrong with illusions, as long as they're confusing the other side. A burglar alarm system that consists entirely of some impressive warning stickers and a flashing red light can actually be effective, as long as you don't believe that there's anything else going on. But you know better than to use it on network security, where the warning stickers and the flashing red light are going to be invisible. Unfortunately, many people have firewalls that are in the end no more effective than that, because they've been configured with fundamental problems. A firewall is not a magical protective device that will fix your network security problems no matter what you do with it, and treating it as if it is such a device will merely increase your risk.

There are two main arguments against using firewalls:

Firewalls interfere with the way the Internet is supposed to work, introducing all sorts of problems, annoying users, and slowing down the introduction of new Internet services.

The problems firewalls don't deal with (internal threats and external connections that don't go through the firewall) are more important than the problems they do deal with.

It's true that the Internet is based on a model of end-to-end communication, where individual hosts talk to each other. Firewalls interrupt that end-to-end communication in a variety of ways. Most of the problems that are introduced are the same sorts of problems that are introduced by any security measure. Things are slowed down; things that you want to get through can't; it's hard to introduce changes. Having badge readers on doors introduces the same sorts of problems (you have to swipe the badge and wait for the door to open; when your friends come to meet you they can't get in; new employees have to get badges). The difference is that on the Internet there's a political and emotional attachment to the idea that information is supposed to flow freely and change is supposed to happen rapidly. People are much less willing to accept the sorts of restrictions that they're accustomed to in other environments.

Furthermore, it's truly very annoying to have side effects. There are a number of ways of doing things that provide real advantages and are limited in their spread by firewalls, despite the fact that they aren't security problems. For instance, broadcasting audio and video over the Internet is much easier if you can use multiple simultaneous connections, and if you can get quite precise information about the capabilities of the destination host and the links between you and it. However, firewalls have difficulty managing the connections, they intentionally conceal some information about the destination host, and they unintentionally destroy other information. If you're trying to develop new ways of interacting over the Internet, firewalls are incredibly frustrating; everywhere you turn, there's something cool that TCP/IP is supposed to be able to do that just doesn't work in the real world. It's no wonder that application developers hate firewalls.

Unfortunately, they don't have any better suggestions for how to keep the bad guys out. Think how many marvelous things you could have if you didn't have to lock your front door to keep strangers out; you wouldn't have to sit at home waiting for the repairman or for a package to be delivered, just as a start. The need for security is unavoidable in our world, and it limits what we can do, in annoying ways. The development of the Internet has not changed human nature.

You also hear people say that firewalls are the wave of the past because they don't deal with the real problems. It's true that firewall or no firewall, intruders get in, secret data goes out, and bad things happen. At sites with really good firewalls, these things occur by avoiding the firewalls. At sites that don't have really good firewalls, these things may go on through the firewalls. Either way, you can argue that this shows that firewalls don't solve the problem.

It's perfectly true, firewalls won't solve your security problem. Once again, the people who point this out don't really have anything better to offer. Protecting individual hosts works for some sites and will help the firewall almost anywhere; detecting and dealing with attacks via network monitoring, once again, will work for some problems and will help a firewall almost anywhere. That's basically the entire list of available alternatives. If you look closely at most of the things promoted as being "better than firewalls", you'll discover that they're lightly disguised firewalls marketed by people with restrictive definitions of what a firewall is.