In general, a proxy is something or someone who does something on somebody else's behalf. For instance, you may give somebody the ability to vote for you by proxy in an election.

Proxy services are specialized application or server programs that take users' requests for Internet services (such as FTP and Telnet) and forward them to the actual services. The proxies provide replacement connections and act as gateways to the services. For this reason, proxies are sometimes known as application-level gateways.[3] In this book, when we are talking about proxy services, we are specifically talking about proxies run for security purposes, which are run on a firewall host: either a dual-homed host with an interface on the internal network and one on the external network, or some other bastion host that has access to the Internet and is accessible from the internal machines.

You will also run into proxies that are primarily designed for network efficiency instead of for security; these are caching proxies, which keep copies of the information for each request that they proxy. The advantage of a caching proxy is that if multiple internal hosts request the same data, the data can be provided directly by the proxy. Caching proxies can significantly reduce the load on network connections. There are proxy servers that provide both security and caching; in general, they are better at one purpose than the other.

Proxy services sit, more or less transparently, between a user on the inside (on the internal network) and a service on the outside (on the Internet). Instead of talking to each other directly, each talks to a proxy. Proxies handle all the communication between users and Internet services behind the scenes.

Transparency is the major benefit of proxy services. It's essentially smoke and mirrors. To the user, a proxy server presents the illusion that the user is dealing directly with the real server. To the real server, the proxy server presents the illusion that the real server is dealing directly with a user on the proxy host (as opposed to the user's real host).

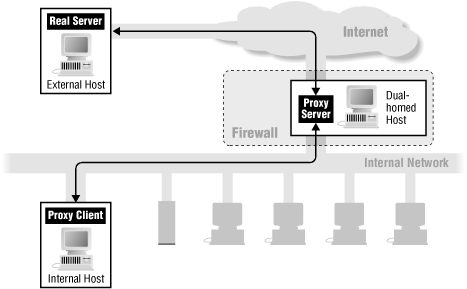

How do proxy services work? Let's look at the simplest case, where we add proxy services to a dual-homed host. (We'll describe these hosts in some detail in Section 6.1.2 in Chapter 6.)

Tip

Proxy services are effective only when they're used in conjunction with a mechanism that restricts direct communications between the internal and external hosts. Dual-homed hosts and packet filtering are two such mechanisms. If internal hosts are able to communicate directly with external hosts, there's no need for users to use proxy services, and so (in general) they won't. Such a bypass probably isn't in accordance with your security policy.

As Figure 5.2 shows, a proxy service requires two components: a proxy server and a proxy client. In this illustration, the proxy server runs on the dual-homed host (as we discuss in Chapter 9, there are other ways to set up a proxy server). A proxy client is a special version of a normal client program (e.g., a Telnet or FTP client) that talks to the proxy server rather than to the "real" server out on the Internet; in some configurations, normal client programs can be used as proxy clients. The proxy server evaluates requests from the proxy client and decides which to approve and which to deny. If a request is approved, the proxy server contacts the real server on behalf of the client (thus the term proxy) and proceeds to relay requests from the proxy client to the real server, and responses from the real server to the proxy client.

In some proxy systems, instead of installing custom client proxy software, you'll use standard software but set up custom user procedures for using it. (We'll describe how this works in Chapter 9.)

There are also systems that provide a hybrid between packet filtering and proxying where a network device intercepts the connection and acts as a proxy or redirects the connection to a proxy; this allows proxying without making changes to the clients or the user procedures.

The proxy server doesn't always just forward users' requests on to the real Internet services. The proxy server can control what users do because it can make decisions about the requests it processes. Depending on your site's security policy, requests might be allowed or refused. For example, the FTP proxy might refuse to let users export files, or it might allow users to import files only from certain sites. More sophisticated proxy services might allow different capabilities to different hosts, rather than enforcing the same restrictions on all hosts.

Some proxy servers do in fact just forward requests on, no matter what they are. These may be called generic proxies or port forwarders. Programs that do this are providing basically the same protections that you would get if you had a packet filter in place that was allowing traffic on that port. You do not get any significant increase in security by replacing packet filters with proxies that do exactly the same thing (you gain some protection against malformed packets, but you lose by adding an attackable proxying program).

Some excellent software is available for proxying. SOCKS is a proxy construction toolkit, designed to make it easy to convert existing client/server applications into proxy versions of those same applications. The Trusted Information Systems Internet Firewall Toolkit (TIS FWTK) includes proxy servers for a number of common Internet protocols, including Telnet, FTP, HTTP, rlogin, X11, and others; these proxy servers are designed to be used in conjunction with custom user procedures. See the discussion of these packages in Chapter 9.

Many standard client and server programs, both commercial and freely available, now come equipped with their own proxying capabilities or with support for generic proxy systems like SOCKS. These capabilities can be enabled at runtime or compile time.

Most proxy systems are used to control and optimize outbound connections; they are controlled by the site where the clients are. It is also possible to use proxy systems to control and optimize inbound connections to servers (for instance, to balance connections among multiple servers or to apply extra security). This is sometimes called reverse proxying.

There are a number of advantages to using proxy services.

Because proxy servers can understand the application protocol, they can allow logging to be performed in a particularly effective way. For example, instead of logging all of the data transferred, an FTP proxy server can log only the commands issued and the server responses received; this results in a much smaller and more useful log.

Since all requests are passing through the proxy service anyway, the proxy can provide caching, keeping local copies of the requested data. If the number of repeat requests is significant, caching can significantly increase performance and reduce the load on network links.

Since a proxy service is looking at specific connections, it is frequently able to do filtering more intelligently than a packet filter. For instance, proxy services are much more capable of filtering HTTP by content type (for instance, to remove Java or JavaScript) and better at virus detection than packet filtering systems.

Because a proxy system is actively involved in the connection, it is easy for it to do user authentication and to take actions that depend on the user involved. Although this is possible with packet filtering systems, it is much more difficult.

As a proxy system sits between a client and the Internet, it generates completely new IP packets for the client. It can therefore protect clients from deliberately malformed IP packets. (You just need a proxy system that isn't vulnerable to the bad packets!)

There are also some disadvantages to using proxy services.

Although proxy software is widely available for the older and simpler services like FTP and Telnet, proven software for newer or less widely used services is harder to find. There's usually a distinct lag between the introduction of a service and the availability of proxying servers for it; the length of the lag depends primarily on how well the service is designed for proxying. This makes it difficult for a site to offer new services immediately as they become available. Until suitable proxy software is available, a system that needs new services may have to be placed outside the firewall, opening up potential security holes. (Some services can be run through generic proxies, which will give at least minimal protection.)

You may need a different proxy server for each protocol, because the proxy server may need to understand the protocol in order to determine what to allow and disallow, and in order to masquerade as a client to the real server and as the real server to the proxy client. Collecting, installing, and configuring all these various servers can be a lot of work. Again, you may be able to use a generic proxy, but generic proxies provide only the same sorts of protection and functionality that you could get from packet filters.

Products and packages differ greatly in the ease with which they can be configured, but making things easier in one place can make it harder in others. For example, servers that are particularly easy to configure can be limited in flexibility; they're easy to configure because they make certain assumptions about how they're going to be used, which may or may not be correct or appropriate for your site.

Except for services designed for proxying, you will need to use modified clients, applications, and/or procedures. These modifications can have drawbacks; people can't always use the readily available tools with their normal instructions.

Because of these modifications, proxied applications don't always work as well as nonproxied applications. They tend to bend protocol specifications, and some clients and servers are less flexible than others.

[3] Firewall terminologies differ. Whereas we use the term proxy service to encompass the entire proxy approach, other authors refer to application-level gateways and circuit-level gateways. Although there are small differences between the meanings of these various terms, which we'll explore in Chapter 9, in general our discussion of proxies refers to the same type of technology other authors mean when they refer to these gateway systems.