The details of how proxying works differ from service to service. Some services provide proxying easily or automatically; for those services, you set up proxying by making configuration changes to normal servers. For most services, however, proxying requires appropriate proxy server software on the server side. On the client side, it needs one of the following:

- Proxy-aware application software

With this approach, the software must know how to contact the proxy server instead of the real server when a user makes a request (for example, for FTP or Telnet), and how to tell the proxy server what real server to connect to.

- Proxy-aware operating system software

With this approach, the operating system that the client is running on is modified so that IP connections are checked to see if they should be sent to the proxy server. This mechanism usually depends on dynamic runtime linking (the ability to supply libraries when a program is run). This mechanism does not always work and can fail in ways that are not obvious to users.

- Proxy-aware user procedures

With this approach, the user uses client software that doesn't understand proxying to talk to the proxy server and tells the proxy server to connect to the real server, instead of telling the client software to talk to the real server directly.

- Proxy-aware router

With this approach, nothing on the client's end is modified, but a router intercepts the connection and redirects it to the proxy server or proxies the request. This requires an intelligent router in addition to the proxy software (although the routing and the proxying can co-exist on the same machine).

The first approach is to use proxy-aware application software for proxying. There are a few problems associated with this approach, but it is becoming easier as time goes on.

Appropriate proxy-aware application software is often available only for certain platforms. If it's not available for one of your platforms, your users are pretty much out of luck. For example, the Igateway package from Sun (written by Jim Thompson) is a proxy package for FTP and Telnet, but you can use it only on Sun machines because it provides only precompiled Sun binaries. If you're going to use proxy software, you obviously need to choose software that's available for the needed platforms.

Even if software is available for your platforms, it may not be software your users want. For example, dozens of FTP client programs are on the Macintosh. Some of them have really impressive graphical user interfaces. Others have other useful features; for example, they allow you to automate transfers. You're out of luck if the particular client you want to use, for whatever reason, doesn't support your particular proxy server mechanism. In some cases, you may be able to modify clients to support your proxy server, but doing so requires that you have the source code for the client, as well as the tools and the ability to recompile it. Few client programs come with support for any form of proxying.

The happy exception to this rule is web browsers like Netscape, Internet Explorer, and Lynx. Many of these programs support proxies of various sorts (typically SOCKS and HTTP proxying). Most of these programs were written after firewalls and proxy systems had become common on the Internet; recognizing the environment they would be working in, their authors chose to support proxying by design, right from the start.

Using application changes for proxying does not make proxying completely transparent to users. The application software still needs to be configured to use the appropriate proxy server, and to use it only for connections that actually need to be proxied. Most applications provide some way of assisting the user with this problem and partially automating the process, but misconfiguration of proxy software is still one of the most common user problems at sites that use proxies.

In some cases, sites will use the unchanged applications for internal connections and the proxy-aware ones only to make external connections; users need to remember to use the proxy-aware program in order to make external connections. Following procedures they've become accustomed to using elsewhere, or procedures that are written in books, may leave them mystified at apparently intermittent results as internal connections succeed and external ones fail. (Using the proxy-aware applications internally will work, but it can introduce unnecessary dependencies on the proxy server, which is why most sites avoid it.)

Instead of changing the application, you can change the environment around it, so that when the application tries to make a connection, the function call is changed to automatically involve the proxy server if appropriate. This allows unmodified applications to be used in a proxied environment.

Exactly how this is implemented varies from operating system to operating system. Where dynamically linked libraries are available, you add a library; where they are not, you have to replace the network drivers, which are a more fundamental part of the operating system.

In either case, there may be problems. If applications do unexpected things, they may go around the proxying or be disrupted by it. All of the following will cause problems:

Statically linked software

Software that provides its own dynamically linked libraries for network functions

Protocols that use embedded port numbers or IP addresses

Software that attempts to do low-level manipulation of connections

Because the proxying is relatively transparent to the user, problems with it are usually going to be mysteries to the user. The user interface for configuring this sort of proxying is also usually designed for the experienced administrator, not the naive user, further confusing the situation.

With the proxy-aware procedure approach, the proxy servers are designed to work with standard client software; however, they require the users of the software to follow custom procedures. The user tells the client to connect to the proxy server and then tells the proxy server which host to connect to. Because few protocols are designed to pass this kind of information, the user needs to remember not only what the name of the proxy server is, but also what special means are used to pass the name of the other host.

How does this work? You need to teach your users specific procedures to follow for each protocol. Let's look at FTP. Imagine that Amalie Jones wants to retrieve a file from an anonymous FTP server (e.g., ftp.greatcircle.com). Here's what she does:

Using any FTP client, she connects to your proxy server (which is probably running on the bastion host — the gateway to the Internet) instead of directly to the anonymous FTP server.

At the username prompt, in addition to specifying the name she wants to use, Amalie also specifies the name of the real server she wants to connect to. If she wants to access the anonymous FTP server on ftp.greatcircle.com, for example, then instead of simply typing "anonymous" at the prompt generated by the proxy server, she'll type "anonymous@ftp.greatcircle.com".

Just as using proxy-aware software requires some modification of user procedures, using proxy-aware procedures places limitations on which clients you can use. Some clients automatically try to do anonymous FTP; they won't know how to go through the proxy server. Some clients may interfere in simpler ways, for example, by providing a graphical user interface that doesn't allow you to type a username long enough to hold the username and the hostname.

The main problem with using custom procedures, however, is that you have to teach them to your users. If you have a small user base and one that is technically adept, it may not be a problem. However, if you have 10,000 users spread across four continents, it's going to be a problem. On the one side, you have hundreds of books, thousands of magazine articles, and tens of thousands of Usenet news postings, not to mention whatever previous training or experience the users might have had, all of which attempt to teach users the standard way to use basic Internet services like FTP. On the other side is your tiny voice, telling them how to use a procedure that is at odds with all the other information they're getting. On top of that, your users will have to remember the name of your gateway and the details of how to use it. In any organization of a reasonable size, this approach can't be relied upon.

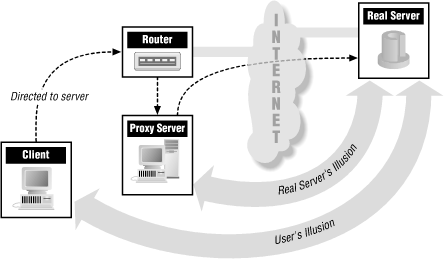

With a proxy-aware router, clients attempt to make connections the same way they normally would, but the packets are intercepted and directed to a proxy server instead. In some cases, this is handled by having the proxy server claim to be a router. In others, a separate router looks at packets and decides whether to send them to their destination, drop them, or send them to the proxy server. This is often called hybrid proxying (because it involves working with packets like packet filtering) or transparent proxying (because it's not visible to clients).

A proxy-aware router of some sort (like the one shown in Figure 9.2) is the solution that's easiest for the users; they don't have to configure anything or learn anything. All of the work is done by whatever device is intercepting the packets, and by the administrator who configures it.

On the good side, this is the most transparent of the options. In general, it's only noticeable to the user when it doesn't work (or when it does work, but the user is trying to do something that the proxy system does not allow). From the user's point of view, it combines the advantages of packet filtering (you don't have to worry about it, it's automatic) and proxying (the proxy can do caching, for instance).

From the administrator's point of view, it combines the disadvantages of packet filtering with those of proxying:

It's easy for accidents or hostile actions to make connections that don't go through the system.

You need to be able to identify the protocol based on the packets in order to do the redirection, so you can't support protocols that don't work with packet filtering. But you also need to be able to make the actual connection from the proxy server, so you can't support protocols that don't work with proxying.

All internal hosts need to be able to translate all external hostnames into addresses in order to try to connect to them.