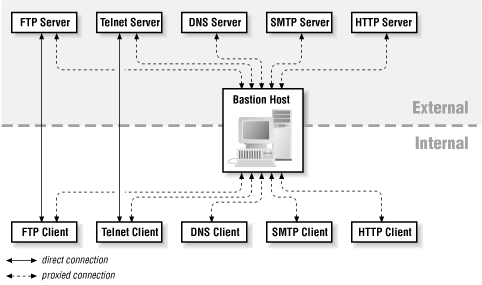

A bastion host provides any services your site needs to access the Internet, or wants to offer to the Internet — services you don't feel secure providing directly via packet filtering. (Figure 10.1 shows a typical set.) You should not put any services on a bastion host that are not intended to be used to or from the Internet. For example, it shouldn't provide booting services for internal hosts (unless, for some reason, you intend to provide booting services for hosts on the Internet). You have to assume that a bastion host will be compromised, and that all services on it will be available to the Internet.

You can divide services into four classes:

- Services that are secure

Services in this category can be provided via packet filtering, if you're using this approach. (In a pure-proxy firewall, everything must be provided on a bastion host or not provided at all.)

- Services that are insecure as normally provided but can be secured

Services in this category can be provided on a bastion host.

- Services that are insecure as normally provided and can't be secured

These services will have to be disabled and provided on a victim host (discussed earlier) if you absolutely need them.

- Services that you don't use or that you don't use in conjunction with the Internet

You must disable services in this category.

We'll discuss individual services in detail in later chapters, but here we cover the most commonly provided and denied services for bastion hosts.

Electronic mail (SMTP) is the most basic of the services bastion hosts normally provide. You may also want to access or provide information services such as:

- FTP

File transfer

- HTTP

Hypertext-driven information retrieval (the Web)

- NNTP

Usenet news

In order to support any of these services (including SMTP), you must access and provide Domain Name System (DNS) service. DNS is seldom used directly, but it underlies all the other protocols by providing the means to translate hostnames to IP addresses and vice versa, as well as providing other distributed information about sites and hosts.

Many services designed for local area networks include vulnerabilities that attackers can exploit from outside, and all of them are opportunities for an attacker who has succeeded in compromising a bastion host. Basically, you should disable anything that you aren't going to use, and you should choose what to use very carefully.

Bastion hosts are odd machines. The relationship between a bastion host and a normal computer on somebody's desktop is the same as the relationship between a tractor and a car. A tractor and a car are both vehicles, and to a limited extent they can fulfill the same functions, but they don't provide the same features. A bastion host, like a tractor, is built for work, not for comfort. The result is functional, but mostly not all that much fun.

For the most part, we discuss the procedures to build a bastion host with the maximum possible security that allows it to provide services to the Internet. Building this kind of bastion host out of a general-purpose computer means stripping out parts that you're used to. It means hearing people say "I didn't think you could turn that off!" and "What do you mean it doesn't run any of the normal tools I'm used to?", not to mention "Why can't I just log into it?" and "Can't you turn on the software I like just for a little while?" It means learning entirely new techniques for administering the machine, many of which involve more trouble than your normal procedures.

In an ideal world, you would run one service per bastion host. You want a web server? Put it on a bastion host. You want a DNS server? Put it on a different bastion host. You want outgoing web access via a caching proxy? Put it on a third bastion host. In this situation, each host has one clear purpose, it's difficult for problems to propagate from one service to another, and each service can be managed independently.

In the real world, things are rarely this neat. First, there are obvious financial difficulties with the one service, one host model—it gets expensive fast, and most services don't really need an entire computer. Second, you rapidly start to have administrative difficulties. What's the good in having one firewall if it's made up of 400 separate machines?

You are therefore going to end up making trade-offs between centralized and distributed services. Here are some general principles for grouping services together into sensible units:

- Group services by importance

If you have services that your company depends on (like a customer-visible web site) and services you could live without for a while (like an IRC server), don't put them on the same machine.

- Group services by audience

Put services for internal users (employees, for instance) on one machine, services for external users (customers, for instance) on another, and housekeeping services that are only used by other computers (like DNS) on a third. Or put services for faculty on one machine and services for students on a different one.

- Group services by security

Put trusted services on one machine, and untrusted services on another. Better yet, put the trusted services together and put each untrusted service on a separate machine, since they're the ones most likely to interfere with other things.

- Group services by access level

Put services that deal with only publicly readable data on one machine, and services that need to use confidential data on another.

Sometimes these principles will be redundant (the unimportant services are used by a specific user group, are untrustworthy, and use only public data). Sometimes, unfortunately, they will be conflicting. There is no guarantee that there is a single correct answer.