The existence of the World Wide Web is a major factor behind the explosive growth of the Internet. (In fact, many of the newcomers to the Internet believe that the Internet and the World Wide Web are the same thing.) Since the first graphical user interface to the Web to gain widespread acceptance, NCSA Mosaic, was introduced in 1993, web traffic on the Internet has been growing at an explosive rate, far faster than any other kind of traffic (SMTP email, FTP file transfers, Telnet remote terminal sessions, etc.). You will certainly want to let your users use a browser to access web sites, and you are very likely to want to run a site yourself, if you do anything that might benefit from publicity. This chapter discusses the underlying mechanisms involved, their security implications, and the measures you can take to deal with them.

The very things that make the Web so popular also make it very difficult to secure. The basic protocols are very flexible, and the programs used for web servers and clients are easy to extend. Each extension has its own security implications, but they are difficult to separate and control.

Most web browsers are capable of using protocols other than HTTP, which is the basic protocol of the Web. For example, these browsers are usually also Gopher and FTP clients or are capable of using your existing Telnet and FTP clients transparently (without it being obvious to the user that an external program is starting). Many of them are also NNTP and SMTP clients. They use a single, consistent notation called a Uniform Resource Locator (URL) to specify connections of various types.

In addition, a number of other protocols are used in conjunction with web browsers. Some of these have other client programs, but most of them are used primarily if not exclusively as a seamless part of web sites.

There are three basic sets of security concerns regarding HTTP:

What can a malicious client do to your HTTP server?

What can a malicious HTTP server do to your clients?

What else can come in, tunneled over HTTP?

The following sections describe these concerns.

A server that supports nothing but the bare HTTP protocol poses relatively few security concerns. An HTTP server with no extensions takes requests and returns files; the only thing it writes to the disk are log files. Therefore, no matter how malicious the user and how badly written the server, the vulnerabilities of an HTTP server by itself are pretty much limited to various sorts of denial of service (the HTTP server crashes, crashes the machine, makes the rest of the machine unusable, fills up the disk . . .) and inadvertent release of data (a client requests a file you wanted to keep private, but the server gives it out). If the server is sufficiently badly written, an attacker may be able to execute arbitrary commands with the permissions of the HTTP server via a buffer overflow attack. This is unlikely in a simple server and relatively easy to protect against (run the server as an account with no special privileges, and even if an attacker can execute commands he or she won't get any interesting results).

Denial of service is always impossible to protect against completely, but a well-written HTTP server will be relatively immune to it. Normal practices for dealing with bastion hosts (see Chapter 10) will also help you avoid and recover from denial of service attacks. Publicly accessible web sites are high-visibility targets and tend to be resource-intensive even when they are not under attack, so it is probably unwise to combine them on the same bastion host with other services.

Inadvertent release of data is a problem that requires more special effort to avoid. You should assume that any file that an HTTP server can read is a file that it will give out. Don't assume that a file is safe because it's not in the document tree, because it's not in HTML, or because you haven't published a link to it. It's easy to get caught out; one of the authors sent out email to a bunch of friends about a web page, only to get an answer back 20 minutes later that said "Interesting, but I don't like the picture of me." "What picture of you? You're not on that web page!" "No, but I always look at the whole directory, and when I saw there was a .gif file named after me I had to look at it." That was a combination of a mistake on the author's part (transferring an entire working directory into production instead of just the parts intended to be published) and on the site maintainer's part (it shouldn't have been giving out directory information anyway).

In this case, the effect was benign, but the same sort of mistake can have much more serious consequences. Public web servers frequently make headlines by containing draft or prerelease information erroneously left with information intended to be published; information intended for a small audience but left unprotected in the hope that nobody will notice it; and information used internally by the web server or other processes on the machine but left where the web server can read it and outsiders can request it. That latter category can include everything from Unix password files to customer data (including credit card numbers!).

In order to minimize these exposures:

Carefully configure the security and access control features of your server to restrict its capabilities and what users can access with it.

Run the server as an unprivileged user.

Use filesystem permissions to be sure that the server cannot read files it is not supposed to provide access to.

Under Unix, use the chroot mechanism to restrict the server's operation to a particular section of your filesystem hierarchy. You can use chroot either within the server or through an external wrapper program.

Minimize the amount of sensitive information on the machine.

Limit the number of people who can put data on the externally visible web sites; educate those people carefully about the implications of publishing data.

Maintain a clear distinction between production and development servers and specify a cleanup stage before data is moved to the production servers.

In the previous section, we discussed the risks of an HTTP server that processes nothing but the base HTTP protocol and pointed out that they're fairly small. This seems to conflict with the easily observable fact that there are frequent and high-profile break-ins to web sites. The problem is that almost nobody runs an HTTP server without extensions. Almost all HTTP servers make extensive use of external programs or additional protocols. (It used to be that additional protocols were always implemented outside the web server, but for efficiency reasons, it's become common to build extension languages into the web server itself.)

These extensions provide all sorts of capabilities; authoring extensions allow people to add and change web pages using a browser, form-processing extensions allow people to place orders for products, database extensions check the current status of things, active page extensions change the look of a page depending on who's asked for it. Anything that a web server does besides returning an unchanging data file requires some addition to the basic capabilities of the server.

These additions radically change the security picture. Instead of providing an extremely limited interaction, they provide the ability to do all sorts of dangerous things (like write data to the server). Furthermore, many extensions are not simple, limited-function modules; they're general-purpose languages, allowing you to easily add your own insecurity at home. That means that the security of your web server is no longer dependent only on the security of the web server, which you can be relatively confident has been developed by people who know something about security and have a development and debugging process in place, but also on all the add-in programs, which may well have been written in a few minutes by novice programmers with no thoughts about security.

Even if you don't install locally written programs, commercial web server extensions have a long and dark history of security problems. It's pretty easy to write a secure program if it never has to write data. It's hard to write a secure program that actually lets the user change things; it gets harder if the user has to juggle high-value information (for instance, if you're writing a electronic commerce application that is dealing with data that has real-world effects on goods and money). It can become very difficult to evaluate security if you're trying to provide complete flexibility.

The list of companies with serious security problems in their web server extensions doesn't just read like a who's who of the software industry; it's effectively the complete list of companies that provide web servers or extensions! For instance, Microsoft, Sun, Netscape, and Oracle have all had problems, often repeatedly. Lest you think this a commercial problem, we should point out that both the Apache server and the Squid cache server have had their problems as well.

You will often see external programs used with web servers called CGI scripts, after the Common Gateway Interface (CGI), which specifies how browsers can pass information to servers. You will also often see Active Server Pages (ASP), which is a Microsoft technology for making dynamic pages. New technologies for extensions appear at a rapid rate, but they all have the same sorts of security implications.

There are two things you need to worry about with these extensions:

Can an attacker trick extensions into doing something they shouldn't?

Can an attacker run unexpected external programs?

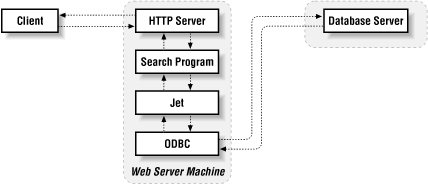

Your average HTTP server runs dozens of external programs; they often come from multiple sources and are written in multiple languages. It's not unusual for a single page to involve three or four layers of programs. For instance, the web server calls an external program written in Visual Basic, which uses Jet to access a database server. In many cases, the people writing web pages are using libraries and may not even be aware what other programs are getting run. Figure 15.1 shows one configuration where a simple query to a web server involves multiple programs.

This situation is a security nightmare. Effectively, each of these external programs is an Internet-attached server, with all the security implications any other server has. If any one of them has security problems, the entire system may be vulnerable; in the previous example, you are vulnerable to problems in the web server, the external program, the Visual Basic interpreter, Jet, and the database server. Both the Visual Basic interpreter and Jet are invisible in normal circumstances, but there have been security problems with Jet.

In the case of a program that accesses a database server, you may not know exactly how it works, but at least you're probably aware that the program is important to you. But security problems may exist and be important even in programs that you think are too trivial to worry about; for instance, there have been security problems with counter programs (which are used to put up the little signs that say "You are visitor number 437"). These programs appear to be pretty harmless; after all, even if people can manipulate the answer they return, who really cares? The difficulty is that they keep the information in a file somewhere, which means that they are capable of both reading and writing files on the machine. Some counter programs can be manipulated into reading or writing any file they have appropriate permissions for, and overwriting arbitrary files with counter information can do a lot of damage.

In order to minimize the risks created by external programs, treat them as you would any other servers. In particular:

Install external programs only after you have considered their security implications and tested them on a protected machine.

Run as few external programs as possible.

Run external programs with minimal permissions.

Don't assume that programs will be accessed from pages or CGI forms you provide.

Develop special bastion host configurations for external programs, going through and removing all unneeded files and double-checking all permissions and placements of files that are read and written.

The most common errors people make are:

Taking a development tool or web server package and installing it on a production machine without removing sample programs or other development features. These are often proof-of-concept or debugging tools that provide very broad access.

Running external programs with too many permissions, either by using an overly powerful account (root, under Unix, for instance), or the same account for a number of different external programs, or a default account provided by a software vendor with normal user access to the entire system (such accounts also often have a known name and password).

More conceptually, people are too trusting; they install combinations of commercial, externally and internally produced programs or scripts without considering their implications. Without suitable training, very few programmers are capable of writing secure programs, and all programs run by a web server need to be secure. No external vendor is so large and clever that you can install their software directly onto your production web server and feel sure that you are secure. No web server add-on is so trivial that you can let a novice programmer write it and not worry about its security.

You must treat every single addition to your web server as a new Internet-available server and evaluate its security appropriately. You must also maintain them all, keeping track of any newly discovered vulnerabilities and making appropriate modifications. Allowing people who are not security-aware to put executable programs on your web server is a recipe for disaster.

The second concern is that attackers might be able to run external programs that you didn't intend to make available. In the worst case, they upload their own external programs and cause your server to run them. How could attackers do this? Suppose the following:

Your HTTP server and your anonymous FTP server both run on the same machine.

They can both access the same areas of the filesystem.

A writable directory is located somewhere in those areas, so that customers can upload crash dumps from your product via FTP for analysis by your programmers, for example.

In this case, the attacker might be able to upload a script or binary to that writable directory using anonymous FTP and then cause the HTTP server to run it.

What is your defense against things like this? Once again, your best bet is to restrict what filesystem areas each server can access (for instance, using chroot under Unix) and to provide a restricted environment in which each server can run. Note that this sort of vulnerability is by no means limited to FTP but is present any time that files can be uploaded.