The Morrison House

The Morrison HouseRobert E. Lee grew up in this town on the Potomac. He lived with his mother in the Federal-style house at 614 Oronoco St., attended services at Christ Church, 118 Washington St., and his home from his marriage until the war was the Custis Mansion in nearby Arlington. While he shopped in the Stabler Leadbeater Apothecary, 105 South Fairfax St., he received orders to go to Harpers Ferry to put down John Brown’s raid.

Alexandria’s best inn, the Morrison House, looks as if it were built in colonial days, but actually the five-story Federal-style building was constructed in 1985. The owner then, Robert E. Morrison, had a Smithsonian curator make sure the inn was authentic to the last luxurious detail.

Antiques at the Winterthur Museum in Delaware were models for many of the furnishings, including sofas upholstered in silk brocade, oversized mahogany canopy beds, and gilt-framed mirrors.

The inn has two restaurants: the award-winning Elysium, which features contemporary upscale American cuisine, and the club-like Grill, which has a piano bar.

Address: 116 South Alfred St., Alexandria, VA 22314;

tel: 703-838-8000 or 800-367-0800; fax: 703-684-6283. Accommodations: Forty-five guest rooms, including three suites.

Amenities: Air-conditioning, parking garage for an additional fee, cable TV in rooms, afternoon tea (extra charge), nightly turndown, health club privileges, butler service, easy walk to historic landmarks.

Rates: $$$, including continental breakfast. All major credit cards except Discover.

Restrictions: No pets, restricted smoking.

Arlington House

Arlington HouseRobert E. Lee loved Arlington House, his mansion on a hill overlooking Washington from across the Potomac. It was built by George Washington Parke Custis, the grandson of Martha Washington by her first marriage, and the father of Mary Anna Randolph Custis, whom Lee married two years after graduating from West Point.

Although the Lees spent much of their married life traveling between army posts, this was home to them for thirty years. Six of their seven children were born here. After Virginia seceded from the Union, it was at Arlington House that Lee made his decision to resign his commission in the U.S. Army rather than bear arms against his native state.

The mansion later became the headquarters of officers supervising the defense of Washington. Later still it was confiscated for back taxes. A two-hundred-acre section of the estate was set aside as an army cemetery, the beginning of Arlington National Cemetery.

Arlington House can be reached from Washington and Alexandria on the Metro trains (Blue Line). Parking is available at the Arlington Cemetery Visitor Center. It is open daily, 9:30-4:30. Admission is free. For information phone 703-557-0613.

Appomattox Court House

Appomattox Court HouseThe end of the line for Robert E. Lee and his Army of Northern Virginia came on Palm Sunday 1865, in this sleepy village, ninety-two miles west of Richmond. His surrender to Ulysses S. Grant did not end the war, but it might as well have. Richmond had fallen, Jefferson Davis and his cabinet were on the run, and William T. Sherman was closing in on Joseph E. Johnston’s army.

On April 9, 1865, Lee was waiting in the parlor of the Wilmer McLean house when Grant rode up. They quickly agreed on the terms of the surrender. After the surrender, Union batteries began to fire salutes, but Grant ordered them stopped. “The war is over,” he said. “The rebels are our countrymen again.”

A formal ceremony was held three days later, during which Lee’s men surrendered their arms and battle flags. As they marched by, Joshua Chamberlain, who was accepting the surrender for Grant, ordered his men to present arms. The Confederates returned the salute, a soldier’s farewell.

Appomattox Court House is open daily, except Federal holidays in the winter; June through August, 9:00-5:30; rest of year, 8:30-5:00. Admission is $2 for adults, children under sixteen free. The national historical park is on VA 24, three miles northeast of Appomattox. For information phone 804-352-8987.

The Bailiwick Inn

The Bailiwick InnIn a skirmish fought across the front lawn of this inn, June 1, 1861, Captain John Quincy Marr, commander of the Warrenton Rifles, became the first Confederate casualty of the Civil War in this area. Governor William “Extra-Billy” Smith, who was in the house at the time, took over command from Marr, thus beginning his military career at the age of sixty-four.

The first major battle of the war was fought five miles away at Manassas in 1861. In 1863, the house was searched by John Mosby’s Raiders during their midnight raid on Fairfax.

One of the first houses built in Fairfax, the house is in the National Register of Historic Places. The guest rooms, all unique, are furnished with antiques and period reproductions, feather beds, and goose-down pillows, upon which guests will find a chocolate when they turn in.

Innkeepers Bob and Annette Bradley make sure that fresh-cut flowers brighten the foyer, cheery fires burn in fireplaces in book-lined parlors, and silver and crystal grace the breakfast table.

Address: 4023 Chain Bridge Rd., Fairfax, VA 22030; tel: 703-691-2266 or 800-366-7666; fax: 703-934-2112.

Accommodations: Fourteen guest rooms, all named after famous Virginians, all with private baths.

Amenities: Air-conditioning, off-street parking, afternoon tea, candlelight dinner with advance notice (and extra charge), fireplaces.

Rates: $$$. American Express, Visa, MasterCard, and personal checks.

Restrictions: No pets, restricted smoking.

Manassas Battlefield

Manassas BattlefieldThe two battles that took place here in 1861 and 1862 are known in the North as First and Second Bull Run, after a creek that runs through the battlefield; in the South they are called First and Second Manassas, after the nearby town.

The 1861 clash was the first major battle of the war, the one in which Thomas J. Jackson won the nickname “Stonewall.” The fighting was confused. Troops on both sides were green, and some of the Confederates wore blue and some of the Federals wore gray. Fresh rebel reserves arrived in the late afternoon, and the Federals retreated.

The retreat turned into a rout, but the tired rebels were not able to press their advantage. The victory gave the South a false sense of confidence, and convinced the North that the war would not be won easily. It also cost General Irvin McDowell command of the Union army.

The second battle began August 26, 1862, after Stonewall Jackson’s corps reached Union supplies stockpiled at Manassas, took what they could, and retreated a few miles west to a system of ditches that had been dug for a railroad.

General John Pope attacked Jackson, believing the rebels were in retreat. But he found them well entrenched and spoiling for a fight. When Pope’s attack stalled, General James Longstreet struck the Union flank with devastating effect. The fighting that day ended at Henry House Hill, where the Federals were able to halt the Confederates.

The next day Pope, having suffered heavy losses, pulled his army back to Washington. Encouraged by the victory, Lee soon embarked on the invasion of Maryland that culminated in the Battle of Antietam.

Manassas National Battlefield Park, 6511 Sudly Rd., Manassas, VA 20109, is open daily except Christmas, dawn to dusk, the Visitor Center, 8:30-5:00. Admission is $2 for adults, children under seventeen free. The park, which commemorates both battles, is twenty-six miles southwest of Washington, DC. For information phone 703-361-1339.

Belle Boyd Cottage

Belle Boyd CottageBelle Boyd was an attractive young lady who spied for Stonewall Jackson, while operating out of her father’s hotel in Front Royal. She rode her horse across the field where the Battle of Front Royal was being fought to give Jackson details about the size and disposition of the Federal forces. In gratitude, he made her an honorary captain in his regiment.

Sometime later, betrayed by her lover, she was arrested and held in the Old Capitol Prison in Washington. Exchanged after a month, she went back to spying and was imprisoned again in June 1863. Paroled on her promise to leave the country, she was on a blockade runner that was captured by a Union navy vessel. She and the captain fell in love and were married.

The Belle Boyd Cottage, 101 Chester St., Front Royal, VA 22630, is a typical 1860 middle-class house, furnished in the period. It has been restored as a living history museum depicting Warren County during the war. The guided tour includes interesting stories of Belle and her clandestine activities. Open Monday-Friday, 11:00-4:00, and weekends by appointment. Admission is $2 for adults, $1 for children. On the Saturday nearest May 23, the Battle of Front Royal is reenacted nearby. To reach the cottage follow Rte. 522 (Commerce St.) into Front Royal. For information phone 540-636-1446.

Chester House

Chester HouseIn the historical district of Front Royal, near the Belle Boyd Cottage, is a stately Georgian mansion, a 1905 updating of a house built in 1848. The house is a treasure, with intricate woodwork, elaborate dentil molding, crystal chandeliers, Oriental rugs, and family antiques and artwork. The attractive bedrooms overlook an Old English garden with brick paths, a fountain, and statuary. A carriage house has a family suite.

Now an inn, the Chester House has been awarded three stars by the Mobil Guide and three diamonds by the AAA. A half-block from the inn is the Warren Rifles Confederate Museum, which has a collection of flags, arms, uniforms, relics, and personal memorabilia. On U.S. 522 just north of town is a marker noting where Custer executed several of Mosby’s Raiders in 1864. (Two months later, Mosby executed an equal number of Custer’s men near Berryville.)

Address: 43 Chester St., Front Royal, VA 22630; tel: 540-635-3937 or 800-621-0441; fax: 540-636-8695; Web page: www.chesterhouse.com.

Accommodations: Six double rooms, four with private baths.

Amenities: Air-conditioning, off-street parking, complimentary refreshments, lawn games.

Rates: $$ (carriage house $$$), including continental breakfast. All major credit cards, and personal checks.

Restrictions: No children under twelve, no pets, restricted smoking.

Fredericksburg Battlefields

Fredericksburg BattlefieldsWhen Lincoln approved Ambrose Burnside’s plan to drive to Richmond through Fredericksburg, he cautioned the general, “It will succeed if you move rapidly; otherwise not.” Burnside didn’t heed Lincoln’s warning and met with disaster.

In the Battle of Fredericksburg (December 13, 1862) Burnside launched two attacks: one struck the Confederate left at Prospect Hill, the second was aimed at the heart of Lee’s defenses on Marye’s Heights directly behind Fredericksburg. Union soldiers were slaughtered by artillery on the heights, near the mansion Brompton, and by Confederate infantry firing from behind a stone wall at the foot of the hill. By the end of the day Lee had won his most one-sided victory of the war.

The Battle of Chancellorsville (May 1-4, 1863) was another triumph for Lee, this time against General Joseph Hooker. Outnumbered, the defeated Hooker retired across the Rappahannock, and Lee prepared his second invasion of the North. It was during this battle that Stonewall Jackson was mistakenly wounded by his own men; he died eight days later.

The Battle of the Wilderness (May 5-7, 1864) was the first encounter between Lee and General Ulysses S. Grant. When the bloody fighting reached a stalemate, Grant elected to go around Lee and march toward Richmond.

Savage fighting started up again two days later in the Battle of Spotsylvania Court House (May 7-20, 1864), and again the battle produced no clear-cut victory. Grant sidestepped and moved closer to Richmond. The relentless attrition of these battles and those that followed finally destroyed the offensive capabilities of Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia.

The Fredericksburg and Spotsylvania County Battlefields Memorial National Military Park is situated on approximately eight thousand acres and includes parts of all four battlefields. There are other important sites well worth visiting: the museum in the Fredericksburg Visitor Center, at Lafayette Blvd. and Sunken Road; the Fredericksburg National Cemetery, where lie sixteen thousand Federal soldiers, nearly thirteen thousand of them unknown; Chatham Manor, a mansion used as Union headquarters during two of the battles, and later as a field hospital where Clara Barton and Walt Whitman nursed the wounded; and the Stonewall Jackson Shrine (twelve miles south on I-95 to Thornburg exit, then five miles east on VA 606 to Guinea), the plantation office where on May 10, 1863, Jackson died. All these sites are open daily, 9:00-5:00, and 8:30-6:30 during the summer. Admission is $3 for adults, free for children under seventeen. For information phone 540-371-0802.

SURPRISE THE BLUECOATS WITH JACKSON

Lee, badly outnumbered at Chancellorsville, gambled and won, sending Jackson’s corps on a risky twelve-mile forced march around Hooker’s Union army. Jackson took the Union by surprise and carried the day. You can follow in Jackson’s footsteps along a gravel road for the first eight miles. The final miles are along a modern highway. Depending on your physical condition, the hike should take from three to four hours. (Be sure to have someone pick you up when you reach the highway, or it will be a long hike indeed.) Get directions and additional information at the Chancellorsville Visitor Center, 120 Chatham Lane, Fredericksburg, VA, open daily, 9:00-5:00. For information phone 540-786-2880.

Chatham Manor

Chatham ManorWhile the owner of this magnificent mansion was away serving as a Confederate staff officer, the Federal army used it at various times as an artillery position; a communications center; the headquarters of several generals, including Irwin McDowell, Ambrose Burnside, Edwin Sumner, and John Gibbon; and a field hospital with the help of Clara Barton, Walt Whitman, and Dr. Mary Walker, the only woman to be awarded the Medal of Honor. Lincoln dined with General McDowell at Chatham while visiting Fredericksburg during the Peninsular Campaign. Yankee soldiers treated the place roughly, using the original paneling as firewood, drawing graffiti on exposed plaster, and riding horses through the first floor.

Chatham was built in 1767-1768 by William Fitzhugh, a staunch supporter of the American cause in the Revolution, and George Washington was a frequent guest. Some historians believe that it was here that Robert E. Lee met his bride to be, Mary Custis, the daughter of George Washington Parke Custis, the grandson of Martha Washington and the adopted son of George Washington.

Chatham Manor, now part of the Fredericksburg and Spotsylvania National Military Park, is open daily, 9:00-5:00, except Christmas and New Year’s Day. Admission is $3 for adults, free for children under seventeen. Five of the ten rooms are open to the public. To reach the property from Fredericksburg take Rte. 3 across the Chatham Bridge, turn left at the first light, then take the next left to Chatham. For information phone 540-371-0802.

The Richard Johnston Inn

The Richard Johnston InnIn 1861 this was a quiet town of five thousand inhabitants, on a railroad and protected by the Rappahannock and Rapidan Rivers. Its strategic location, midway between Washington and Richmond, made it a barrier to a Union invasion of the Confederacy. Engulfed by the war, the town would change hands seven times. Four great battles were fought in and around Fredericksburg. The battles, in which casualties totaled more than 100,000, were distinguished by the military genius of Robert E. Lee.

In the heart of Fredericksburg, across from the Visitor Center, is the Richard Johnston Inn, the namesake of the mayor of Fredericksburg who lived here in the early 1800s. It is a charming 1787 brick row house with a third-floor dormer and a patio that adjoins the parking lot in the rear. One look inside and you know owner Susan Williams has restored and furnished her inn with loving care. Chippendale and Empire-style antiques grace the common room downstairs. The guest rooms include two suites with living rooms, wet bars, and private entrances opening onto the patio. Breakfast is served in the dining room with china, crystal, and silver.

Address: 711 Caroline St., Fredericksburg, VA 22401; tel: 540-899-7606.

Accommodations: Six double rooms and two suites, all with private baths.

Amenities: Air-conditioning, off-street parking, cable TV in three guest rooms. Two friendly dogs in residence.

Rates: $$-$$$, including continental breakfast. American Express, Visa, MasterCard, and personal checks.

Restrictions: No pets, no smoking.

The Kenmore Inn

The Kenmore InnThis building in the historic district, which dates from the late 1700s, took a pounding during the Battle of Fredericksburg, and evidence of the heavy Union shelling is still evident in the roof supports. It was a family dwelling then and remained one until the early 1930s, when it was expanded and made into a small hotel.

Today, it is a gracious and luxurious inn, perfectly located for guests to explore the Civil War battlefields and historic buildings in Fredericksburg and the surrounding area. The guest rooms are warm and comfortable, with working fireplaces, decanters of sherry, and tea and cookies in the afternoon. The inn has an excellent restaurant and a pub with live music on the weekends.

Innkeeper Edward Bannon does a fine job of keeping everything as it should be. The Fredericksburg Visitor Center is a short walk away, and the streets abound with antique shops. No one who is interested in the Civil War should miss Fredericksburg; no one who enjoys gracious living should miss the Kenmore Inn.

Address: 1200 Princess Anne St., Fredericksburg, VA 22401; tel: 540-371-7622; fax: 540-371-5480.

Accommodations: Twelve guest rooms, all with private baths.

Amenities: Fireplaces and canopy beds in some rooms, sherry, tea, and cookies in the afternoon, TV in lounge, dining room, and pub.

Rates: $$-$$$. The Modified American Plan, which includes breakfast and dinner in the rate, is available with two-day stay. All major credit cards and personal checks.

Restrictions: No pets, restricted smoking.

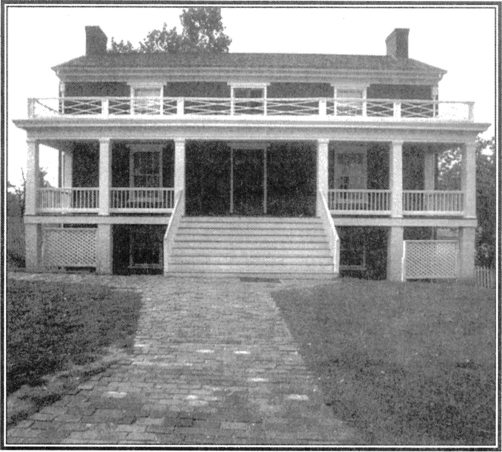

La Vista Plantation

La Vista PlantationAbout six miles from this 1838 plantation house in the countryside south of Fredericksburg is the Stonewall Jackson Shrine, the building where he died after being accidentally wounded by his own men at the Battle of Chancellorsville.

La Vista has also seen a lot of history. After the Battle of Spotsylvania, the Fourth Corps of the Union army came through the nearby fields like a swarm of angry bees. And Stonewall’s ghost may be in residence here, perhaps because the bed in which he died was stored here for many years.

The present owners of La Vista, Michele and Edward Schiesser, who is the chief of exhibits and design at the Hirshhorn Museum in Washington, report that a sound near the front door is heard “virtually every other day.” On other occasions they have heard someone, or something, stomping upstairs. Guests tell of whispers when no one else was in the room, and of a soldier standing in the front yard. However, all this merely adds a dash of mystery to a visit to this inn.

The inn has high ceilings, heart-of-pine floors, acorn moldings, and a handsome two-story portico. On the ten-acre grounds is a pond stocked with bass. The bedroom on the main floor has a king-size mahogany four-poster. The bedroom in the English basement has a queen-size cherry pencil post bed, a double bed, and a sitting room with a queen sleep sofa, and easily accommodates a small family. Both bedrooms have working fireplaces.

Address: 4420 Guinea Station Rd., Fredericksburg, VA 22408; tel: 540-898-8444 or 800-529-2823; fax: 540-898-9414; E-mail: LAVISTABB@aol.com.

Accommodations: One bedroom and one apartment, both with private baths.

Amenities: Air-conditioning, off-street parking; phone, TV, and refrigerator in rooms, complimentary ice and sodas, golf and tennis nearby.

Rates: $$. Visa, MasterCard, and personal checks.

Restrictions: No pets, no smoking.

The Stonewall Jackson Shrine

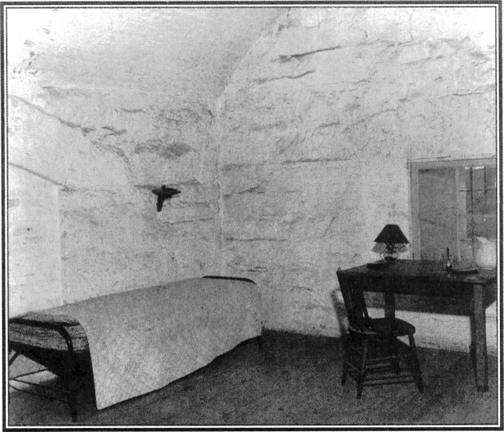

The Stonewall Jackson Shrine

As darkness fell on the Battle of Chancellorsville, Stonewall Jackson was mortally wounded by shots mistakenly fired by his own troops. He was taken to a field hospital near Wilderness Tavern, where his left arm was amputated. Lee sent word to him, “You have lost your left arm, I have lost my right.”

On May 4, Jackson endured a twenty-seven-mile ambulance ride to Fairfield Plantation at Guinea Station and was placed in a small office building by the railroad. The plan was to take Jackson by train to Richmond after he regained sufficient strength. But he contracted pneumonia, his condition worsened, and he died on May 10, 1863, after murmuring, “Let us pass over the river, and rest under the shade of the trees.”

The Stonewall Jackson Shrine is twelve miles south of Fredericksburg on I-95 to the Thornburg exit, then five miles east on VA 606. It is part of and administered by the Fredericksburg and Spotsylvania National Military Park. The small bedroom on the second floor of the building is as it was the day Jackson passed away. The shrine is open daily, 9:00-5:00, from mid-June to Labor Day; Friday-Monday, March to mid-June and Labor Day through October; weekends the rest of the year. Admission is $3 for adults, free for children under seventeen. For information phone 540-371-0802.

Stratford Hall

Stratford HallThis plantation, one of the grandest in Virginia, was the ancestral home of the Lees. Thomas Lee built the house in the 1730s, and here Robert E. Lee was born on January 19, 1807. Four years later his father’s disastrous speculation in land left him virtually penniless, forcing him to move the family to Alexandria. All his adult life Robert E. Lee dreamed of owning Stratford Hall, but it was not to be. The house is an H-shaped fortress-like mansion with imposing chimney clusters. The southeast bedroom, called the Mother’s Room, is where many of the Lee children, including Robert, were born. Lee’s cradle is by the window. The house is furnished throughout with period antiques and family portraits. The plantation, originally encompassing sixteen thousand acres, now consists of sixteen hundred. The many original outbuildings include the kitchen, smokehouse, coach house, grist mill, slave quarters, and stables. The restored boxwood gardens are handsome.

Stratford Hall is a forty-five-minute drive east of Fredericksburg. Take Rte. 218 and VA 3 to Montross, then drive six miles north on Rte. 3, then east on Rte. 214. It is open daily, 9:00-4:30, except Thanksgiving, Christmas, and New Year’s Day. The Visitor Center has a museum and a theater with an audiovisual presentation. Costumed docents conduct tours. A plantation lunch is served, 11:00-3:00. Admission is $7 for adults, $6 for seniors, and $3 for children. For information phone 804-493-8038.

Richmond

RichmondRichmond was the symbol of the Confederacy. It was the seat of its government, its largest manufacturing center, and the primary supply depot for troops operating on the Confederacy’s northern frontier.

Early in the war, the North decided that if Richmond could be captured, the South would sue for peace. Seven major campaigns were launched against Richmond, two of which brought Union armies within sight of the city. The first was George B. McClellan’s Peninsular Campaign of 1862, which was thwarted by Robert E. Lee. During the series of battles called the Seven Days, Lee sent the Union army reeling back toward Washington. In 1864, though, Ulysses S. Grant’s crushing overland campaign finally captured Richmond, and the Confederacy came tumbling down.

There is clearly much of Civil War interest to see and do in Richmond. One of the most important sites is the Richmond National Battlefield Park, which consists of ten units comprising 770 acres. Start at the Chimborazo Visitor Center, 3215 E. Broad St. It occupies the site of the Confederacy’s largest hospital, Chimborazo. Considered a medical marvel, it accommodated the flood of wounded arriving daily in the city, a total of nearly 76,000 during the war.

At the Visitor Center, museum, exhibits, and an audiovisual program depict the complexity of the defense of Richmond. The center also is the first stop on a fifty-six-mile, self-guided auto tour of the park. It takes a full day and includes sites associated with both the 1862 and 1864 campaigns. A map available at the center shows visitors how to select their own route, visiting some or all of the sites. Time permitting, the sites of the 1862 campaign should be visited on one day, the 1864 sites on another. The Visitor Center is open daily, 9:00-5:00. For information phone 804-226-1981.

The 1862 campaign sites include Chickahominy Bluff, where Lee watched the beginning of the Seven Days’ Battles; Beaver Dam Creek, part of the three-mile Union front that the Confederates unsuccessfully assaulted; Watt House, on the Gaines’s Mill Battlefield, which was the headquarters of General Fitz-John Porter during a crucial point in the fighting; Malvern Hill, where the last battle of the Seven Days was fought; and Drewry’s Bluff, where Confederate cannon guarded the James River approach to Richmond.

The 1864 campaign sites on the tour include Cold Harbor, where Grant suffered terrible losses while attacking Lee’s well-entrenched position, and Fort Harrison, a key position captured by Grant.

A Richmond treasure is the White House of the Confederacy, the home of President Davis and his family until Richmond fell in April 1865. The handsome house contains many original furnishings and personal items. Ten rooms have been restored to their wartime appearance, and the first floor contains a central parlor where the Davises entertained. Davis’s offices and the family bedrooms are on the second floor.

The adjacent Museum of the Confederacy contains the nation’s largest collection of Confederate weapons, uniforms, battle flags, letters, diaries, photographs, equipment, and other artifacts. Among the displays are Lee’s field equipment, a model of the ironclad Virginia, made by a crewman, the sword Lee wore at the surrender, and Jeb Stuart’s plumed hat.

Both attractions are open Monday-Saturday, 10:00-5:00, and Sunday, 12:00-5:00. A combined ticket is $8 for adults, $7 for seniors, and $5 for ages six through college. For information phone 804-649-1861.

Many important events of the war occurred in the State Capitol, on Capitol Square one block south of Broad St. For example, Virginia ratified the Articles of Secession, Lee assumed command of all Virginia forces, and the Confederate Congress met in the building. Open daily, 9:00-5:00, except Thanksgiving, Christmas, and New Year’s Day; December through March, open Sunday, 1:00-5:00. Thirty-minute tours are available, the last one beginning at 4:00. Admission is free. For information phone 804-698-1788.

Saint Paul’s Episcopal Church, southwest corner of Grace and Ninth, was known as the “Church of the Confederacy.” President Davis received confirmation in the Episcopal faith here early into the war, and he was attending a service on April 2, 1865, when he received a message from Lee that the Petersburg defenses had been broken and Richmond had to be evacuated. Open daily, 10:00-4:00. For information phone 804-643-3589.

Battle Abbey, 428 North Blvd., was built in 1913 as a Confederate memorial. It is now the home of the Virginia Historical Society and their Museum of Virginia. Among other exhibits, the museum boasts the Maryland-Steuart Collection of Confederate-made weapons, considered to be the world’s finest. There is a library onsite and educational programs are offered daily. A mammoth mural series by Charles Hoffbauer depicts The Four Seasons of the Confederacy. Open daily, 10:00-5:00, except Sunday, 1:00-5:00. Admission is $4 for adults, $3 for seniors, and $2 for children and students. For information phone 804-358-4901.

Hollywood Cemetery, 412 S. Cherry St. at Albermarle. The notables buried here include James Monroe, John Tyler, Jefferson Davis, and J. E. B. Stuart. Some fifteen thousand Confederate soldiers are also interred in the 115-acre cemetery, which was opened in 1853. The cemetery office at the gate offers an audiovisual program and a map showing the location of the prominent graves. Open daily. For information phone 804-648-8501.

Linden Row Inn

Linden Row InnThe Greek Revival town houses that make up what is known as Linden Row have been a Richmond landmark since 1847. They shared a garden that was the childhood playground of Edgar Allan Poe and the inspiration for the “enchanted garden” in his poems. During the war, the two westernmost houses were occupied by the Southern Female Institute, and President Jefferson Davis riding by on horseback was a familiar morning sight.

Linden Row is rated an AAA Four Diamond Inn, and is listed on the National Register. Furnished in the Victorian style, the inn’s original features include fireplaces with marble mantels and crystal chandeliers. Snacks and refreshments are served on the patio, and the dining room features Southern cuisine. Guests enjoy a complimentary wine and cheese reception in the parlor. The inn is within walking distance of the Capitol, the Museum and White House of the Confederacy, and the Valentine Museum.

Address: 100 E. Franklin St., Richmond, VA 23219; tel: 804-783-7000; fax: 804-648-7504.

Accommodations: Seventy guest rooms (including seven parlor suites), all with private baths.

Amenities: Climate-controlled rooms, cable TV and clock-radio in rooms, afternoon refreshments, use of nearby fitness center, valet parking, free transportation to downtown.

Rates: $$ in garden court, $$$ in main house, including continental breakfast. All major credit cards and personal checks

Restrictions: No pets, restricted smoking.

Emmanuel Hutzler House

Emmanuel Hutzler HouseMemories of the war were stirred in the capital city on May 7, 1890, when J. A. C. Mercie’s statue of Robert E. Lee, hat in hand and astride his horse Traveller, was loaded on four gaily covered wagons and hauled by men, women, and children to its present location. It was dedicated three weeks later before a crowd of 100,000, unveiled by Joseph E. Johnston, assisted by Wade Hampton and Fitzhugh Lee. The only inscription on the statue is LEE. The statue was erected on the newly laid out Monument Avenue, a broad mall that would become the city’s boulevard of honor, lined by handsome mansions.

One mansion, of Italian Renaissance design and a few steps away from the Lee statue, now houses this comfortable inn. Mahogany paneling is used extensively in its eight-thousand-square-foot interior, and innkeepers Lyn Benson and John Richardson have furnished it with period pieces. They have retained the best of the past, while adding such modern-day amenities as air-conditioning and new bathrooms.

Address: 2036 Monument Ave., Richmond VA 23220; tel: 804-353-6900 or 804-355-4885; fax: 804-355-5053.

Accommodations: Four double rooms, all with private baths, two with Jacuzzis.

Amenities: Air-conditioning, off-street parking, phone and TV in rooms.

Rates: $$-$$$. All major credit cards and personal checks.

Restrictions: No children under twelve, no pets (pet boarding nearby), no smoking.

The William Catlin House

The William Catlin HouseThis house in the historic Church Hill District was built in 1845 for William Catlin by one of the finest masons in the country. A block away is St. John’s Church, where Patrick Henry demanded “liberty or death.” The inn also is convenient to the Virginia State Capitol, where Lee was sworn in as commander of Virginia’s armed forces in the Civil War, and Shockoe Slip with its restaurants and shops.

Now the house is an inn, richly appointed with antiques and family heirlooms and hosted by Robert and Josephine Martin, who live in the house to make sure everything runs smoothly. Guests are pampered with bedroom fireplaces, goose-down pillows, and, at night, a chocolate mint and a glass of sherry. Coffee or tea is waiting in the morning, and the full breakfast is a testament to Southern hospitality. For an informal dinner try the restaurant at Mr. Patrick Henry’s Inn next door (804-644-1322).

Address: 2304 E. Broad St., Richmond, VA 23223; tel: 804-780-3746.

Accommodations: Five bedrooms, three with private baths and two with shared bath.

Amenities: Air-conditioning, fireplaces in rooms.

Rates: $$, including full breakfast. Visa, MasterCard, Discover, and personal checks.

Restrictions: No pets, no smoking.

Berkeley Plantation

Berkeley PlantationThis plantation on the north bank of the James River was the home of the Harrisons, the prominent Virginia family that included a signer of the Declaration of Independence and two presidents, William Henry Harrison and Benjamin Harrison. The land was part of a royal grant in 1619; the house was built in 1726. In 1862, General McClellan established his Peninsular Campaign headquarters here. Lincoln came to Berkeley twice to consult with McClellan and review the 140,000 troops that were camped nearby. While here, General Daniel Butterfield composed the bugle call “Taps.” After Lee drove McClellan from the gates of Richmond in the Seven Days’ Battles, McClellan’s army retreated here to board ships to return to Washington. In 1907, Berkeley was purchased by John Jamieson, who had camped at the plantation when he was a drummer boy with the Union forces. The house has been restored and furnished with period pieces.

Berkeley Plantation, off Rte. 5, about a thirty-minute drive from Richmond, is open daily, 8:00-5:00, except Christmas. An audiovisual presentation is a prelude to a tour of the house and grounds. Admission is $8.50 for adults, $7.65 for seniors, $6.50 for children thirteen to sixteen, and $4 for children six to twelve. The Coach House Restaurant serves lunch daily and dinner by reservation only. For information phone 804-829-6018.

Shirley Plantation

Shirley PlantationThis handsome, three-story brick house on the James River was the ancestral home of Robert E. Lee’s mother, Anne Carter Lee. After his father suffered financial reverses, the boy lived here for a while and attended the plantation school with his cousins. During the Civil War, wounded Federal troops were brought to the lawn around the house after the nearby Battle of Malvern Hill. One Carter resident wrote that “they lay all about on this lawn and all up and down the river bank. Nurses went about with buckets of water and ladles for them to drink and bathe their faces … Mama had to tear up sheets and pillow cases to bind their wounds, and we made them soup and bread every day until they died or were carried away.” General McClellan sent a letter, “with the highest respect,” thanking the Carters for their aid to men “whom you probably regard as bitter foes.”

Shirley Plantation is off Rte. 5, in Charles City County, a forty-minute drive from downtown Richmond. It is open daily, 9:00-5:00, except Thanksgiving, Christmas, and New Year’s Day. Docents lead tours of the house and grounds. Admission is $8.50 for adults, $7.50 for seniors, AAA members, and military, $5.50 for youths thirteen to twenty-one, and $4.50 for children six to twelve. For information phone 804-829-5121.

Edgewood Plantation

Edgewood PlantationThis Gothic house was built in 1849 on land that once belonged to the nearby Berkeley Plantation, and Confederate officers used the third floor to spy on McClellan’s troops when they were camped at Berkeley in 1862. On June 15 of that year, Jeb Stuart stopped by for coffee on his way to Richmond to apprise Lee of the disposition and strength of Federal troops.

The house was built for Spencer Rowland, and one of his daughters scratched her nickname “Lizzie” on the window in one of the bedrooms, where she later died of a broken heart when her lover was killed in the war. Two of the guest rooms are in the slave quarters behind the house; they overlook English gardens and the millrace canal dug by slaves in the 1700s. Over the years the house has been a church, post office, telephone exchange, nursing home, and a restaurant. Now the National Landmark has been modernized, restored to its original glory, and furnished with antiques and period reproductions. Edgewood is an ideal place to stay while exploring the other grand plantations along the James.

Address: 4800 John Tyler Memorial Highway, Charles City, VA 23023; tel: 804-829-2962 or 800-296-3343.

Accommodations: Eight guest rooms, seven with private baths.

Amenities: Air-conditioning, parking area, TV in rooms, billiard room, gift shop, swimming pool.

Rates: $$$. All major credit cards and personal checks.

Restrictions: No children, no pets, restricted smoking.

North Bend Plantation

North Bend PlantationGeneral Philip Sheridan made his headquarters at this plantation in 1864 and his troops dug defensive trenches across its fields to the James River. Their breastworks can still be seen on the eastern edge of the property. The main house contains many mementos of Civil War days. The plantation desk has the original labels on its pigeonholes. Sheridan’s map of the area now hangs in the billiard room.

The present owner of North Bend, George Copland, is the great-grandson of the wartime owner, Edmund Ruffin, who is credited with firing the first shot of the war at Fort Sumter, in April 1861. Copland and his wife have restored the home and grounds to their original beauty. Federal-style mantels and stair carvings survive from the oldest portion of the house, which was built in 1819 for the sister of William Harrison, the ninth president. Also surviving are all the Greek revival features from the 1853 remodeling and many family heirlooms and memorabilia. Of particular interest is a collection of rare books, including volumes of Harpers Pictorial History of the Civil War, copyright 1869.

Address: 12200 Weyanoke Rd., Charles City, VA 23030; tel: 804-829-5176 or 800-841-1479; fax: 804-829-6828.

Accommodations: Four guest rooms, all with private baths.

Amenities: Air-conditioning, ceiling fans; billiard room, library, croquet, horseshoes, and a swimming pool are on the premises.

Rates: $$$. Visa, MasterCard, and personal checks.

Restrictions: No children under six, no pets, restricted smoking.

Petersburg Battlefield

Petersburg BattlefieldAfter an unsuccessful attempt at Cold Harbor to take Richmond by a frontal attack, Grant withdrew and attacked Petersburg. After four days of hard fighting failed to break the Confederate lines, he gave up and laid siege to the city.

Lee couldn’t afford to abandon Petersburg; it was the rail center that furnished his troops with supplies. If it fell, Richmond would surely fall, too. The siege lasted ten months, from June 15, 1864, to April 2, 1865, with the two armies in almost constant contact. When Petersburg finally fell, Lee’s surrender at Appomattox was only a week away.

The Petersburg National Battlefield, on Rte. 36, two miles east of the city off I-95, preserves Union and Confederate fortifications, trenches, and gun pits. A second unit of the park, Five Forks Unit, is located twenty-three miles to the west. It was at Five Forks that Sheridan’s troopers broke through Confederate defenses, which led to the fall of Petersburg and Lee’s retreat. The park is open daily, 8:00-5:50 in the summer, 8:00-5:00 the rest of the year, and is closed for Presidents’ Day, Martin Luther King Day, Thanksgiving, Christmas, and New Year’s Day.

Maps for the self-guided auto tour are available at the Visitor Center. Living history programs are presented daily during the summer. Admission is $4 for adults, free for children sixteen and under. For information phone 804-732-3531.

Other sites of interest in the Petersburg area include the Blandford Church and Cemetery, which has thirteen Louis Comfort Tiffany stained-glass windows celebrating the thirteen states of the Confederacy; the windows were donated by the individual states in memory of the thirty thousand Confederate soldiers buried in the cemetery.

The City Point Unit of the National Battlefield is where, between June 1864 and April 1865, the sleepy village of City Point was transformed into a bustling supply center for the 100,000 Federal troops on the siege lines. On the grounds of the Appomattox Plantation in City Point is the cabin Grant used as his headquarters during the siege.

FOLLOW LEE’S RETREAT FROM PETERSBURG TO APPOMATTOX

With the fall of Petersburg, Lee retreated across the area called Southside Virginia, Grant in hot pursuit. Now you can follow Lee’s route, visiting the sites that played a role in the drama. The 140-mile driving tour takes al least a day. For a map of the route phone 1-800-6-RETREAT. An interpretive radio message at each stop is broadcast on 1610 AM.

Start at the Petersburg Visitor Center in the Old Towne Petersburg historic district, where you can pick up a map of the Retreat as well as books and an audiotape. Beside the Visitor Center is:

1. South Railroad Station (April 2). Lees troops evacuated Petersburg in and around the station after the last supply line was cut. Follow the red, white, and blue trailblazing signs to:

2. Pamplin Park Civil War Site (April 2). At dawn the Federal troops attacked and finally broke Lee’s defensive line. Follow the

3. Sutherland Station (April 2). Grants forces severed the South Side Railroad here, Lee’s last supply line into Petersburg. Now take Rte, 708 to:

4. Namozine Church (April 3). As Lee’s soldiers marched toward Amelia Court House, a rearguard cavalry skirmish took place around this church. Continue on Rte. 708, then right on Rte. 153, and turn left on Rte. 38 and drive about five miles to:

5. Amelia Court House (April 4-5). Confederate troops from Petersburg and Richmond assembled here, hoping to continue on to North Carolina and link up with Johnston’s army. About six miles southwest on Rte. 360 is:

6. Jetersville (April 5). Lee ran into Union forces here and changed his route to go toward Farmville. Continue on Rte. 642 for about six miles to:

7. Amelia Springs (April 6). Here the Federals came in contact with the rebel rearguard as Lee completed a night march to avoid Grant’s forces at Jetersville. Continue for about three miles, turning left on Rte. 617, to:

8. Deatonville (April 6). A brief rearguard action was fought here on the way to Farmville. About two miles along the road is:

9. Holt’s Corner (April 6). At this road junction, part of Lee’s army turned while the main force continued ahead to the crossing of Little Sayler’s Creek. Continue on Rte. 617 to:

10. Hillsman House (April 6). Near this house, which was used as a field hospital, was fought the Battle of Sayler’s Creek, the last major battle of the Army of the Potomac and the Army of Northern Virginia. Federal troops captured more than seven thousand prisoners, a fifth of Lee’s army. Stunned, Lee said: “My God! Has the army dissolved?” About a mile farther is:

11. Marshall’s Crossroads (April 6), While the battle raged at Sayler’s Creek, Union cavalry fought Confederate infantry here. Double back to Rte. 618 at Holt’s Corner, turn left, go to Rte. 619, turn left, and drive on to:

12. Lockett House (April 6). Numerous bullet holes attest to the fighting that took place near the creek close to the house. The house was later used as a field hospital. Proceed on Rte. 619 to:

13. Double Bridges (April 6). The Confederate wagon train and column that turned off at Holt’s Corner became bogged down in crossing Sayler’s Creek here and were attacked by Federal forces. Five miles south on Rte, 619 after it crosses Rte. 307 is:

14. Rice’s Depot (April 6). Lee’s men dug in here to protect the road and skirmished with Federal troops coming from the direction of Burkeville Junction. Proceed to Rte. 460 to:

15. Cavalry Battle at High Bridge (April 6). Some nine hundred Federal troopers, on a mission to burn this South Side Railroad trestle over the Appomattox River, were intercepted and most of them captured. Four miles down the road is:

16. Farmville (April 7). Both armies marched through this tobacco town. Lee, hoping to issue rations to his troops here, was unsuccessful and crossed to the north side of the Appomattox River. Three miles north on Rte. 45 is:

17. Cumberland Church (April 7). Federal forces that had crossed the river at High Bridge attacked Lee’s forces around this church and forced him to delay his march until nightfall. Turn right on Rte. 657 and drive two miles to:

18. High Bridge (April 7). Confederate forces had burned four spans of this bridge, but failed to destroy the lower wagon bridge. This enabled the Federals to continue the pursuit of Lee’s army north of the Appomattox. Circle back to Rte. 636 and proceed to the crossing of Rte. 15.

19. Clifton (April 8). Generais Grant and Meade used this location for their headquarters during the night. Grant stayed in the house and it was here he received Lee’s second letter suggesting a peace meeting. He left the next morning and rode on to Appomattox Court House. Continue on Rte. 636 to:

20. New Store (April 8). At this point, General Lee’s army would change its line of march. They would continue to be pursued by two Union army corps. Take Rte. 636 to Rte. 24, turn left, and go to:

21. Lee’s Rearguard (April 8). Here General Longstreet built breastworks to protect the rear of Lee’s army, most of which was four miles south at Appomattox Court House. Continue on Rte. 24, past the National Historic Park to the town of Appomattox.

22. Battle of Appomattox Station (April 8). In the evening. Union cavalry captured four trains of supplies at the station intended for Lee’s army. Later, after a brief engagement, they also captured portions of the Confederate wagon train and twenty five cannon.

23-26. As an alternate route in driving from Petersburg to Appomattox, following Rte. 460, are stops 23-26: Burkeville (April 5-May 1865); Crewe (April 5-6, 1865); Nottoway Court House (April 5, 1865); and Battle of Nottoway (June 23, 1864).

The Owl and the Pussycat

The Owl and the PussycatA local merchant, John Gill, built this brick Queen Anne-style mansion in 1895, and his descendants occupied it until the 1940s. Now it is an attractive inn, two blocks from the Siege Museum, fifteen minutes from the Petersburg Battlefield, and a half-hour or so drive from the plantations of the lower James River.

The present owners, John and Juliette Swenson, had owned a bed-and-breakfast in Port Townsend, Washington, before coming here. The inn was named after Edward Lear’s famous children’s poem, and the guest rooms reflect the theme: the Owl Room includes the turret of the house, which overlooks the front garden; the Pussycat Room has a collection of teapots; and the Sonnet Room has a collection of books of poetry. Mrs. Swenson, who grew up in Bath, England, often serves Sally Lunn bread with breakfast.

Address: 405 High St., Petersburg, VA 23803; tel: 804-733-0505; fax: 804-862-0694; E-mail: owlcat@ctg.net.

Accommodations: Six guest rooms, two share a bath.

Amenities: Air-conditioning, off-street parking, TV in common room, sun room, badminton, croquet.

Rates: $$, including full breakfast on weekends, continental on weekdays. All major credit cards and personal checks.

Restrictions: $20 cleaning deposit required for pets, no smoking.

Fort Monroe

Fort MonroeThis is the largest stone fort ever built in the United States. Construction began in 1819, and four years later the fort received its first army garrison. In 1831, a young army engineer named Robert E. Lee arrived to help supervise the construction of the fort’s moat.

When war came, the Confederacy did not attempt to seize Fort Monroe. As a result, Virginia had no fort throughout the war, which denied the state access to the sea.

Lincoln visited here to observe the Union attack on Norfolk, and later McClellan used the fort as the springboard for his Peninsular Campaign.

Jefferson Davis, captured after the war, was imprisoned here. First kept in a casement, a chamber in the wall of the fort, he was moved to a room in the fort’s officers’ quarters, and released two years later. His cell, now a museum, has been restored to its appearance when Davis was imprisoned.

The Casement Museum/Fort Monroe, PO Box 51341, Fort Monroe, VA, is open daily, 10:30-4:30. Guided tours with two weeks’ notice for groups of ten or more. To reach the fort from I-64, take Exit 268 and follow the signs to Fort Monroe. For information phone 757-727-3391.

Willow Grove Inn

Willow Grove InnConfederate General A. P. Hill once made his headquarters in this classic plantation house, and the trenches and breastworks his men built are still visible on the spacious grounds. Willow Grove had seen war before. During the Revolution, generals Wayne and Muhlenberg camped here, and later Dolley Madison was a neighbor. The house is in the National Register and is a Virginia Historic Landmark.

The inn stands on a hill overlooking the meadows of the Piedmont region, near where three of the first five presidents lived: Jefferson, Madison, and Monroe. Seven guest rooms are named for Virginia-born presidents and furnished with period pieces.

Despite its impressive historical credentials, Willow Grove is a relaxed, friendly place to stay. What once was the root cellar is now a bar and the scene of weekend sing-alongs. On cold winter nights, fires burn in the fireplaces of the second-floor bedrooms. The meals here are exceptional. Dinner may include smoked Rappahannock trout, shank of venison, saddle of rabbit, local greens, and goat cheese. Particularly popular is the three-course brunch on Sunday.

Willow Grove is expensive, but few historic inns in the country measure up to it.

Address: 14079 Plantation Way, Orange, VA 22960; tel: 540-672-5982 or 800-949-1778; fax: 540-672-3674.

Accommodations: Eight double rooms and two suites, all with private baths.

Amenities: Air-conditioning, off-street parking, restaurant, pre-breakfast tray delivered to room. Civil War Camp reenactment during summer.

Rates: $$$, including full breakfast and dinner. All major credit cards and personal checks.

Restrictions: Notice required if bringing children. Pets allowed in cottages but not in main house. Restricted smoking.

Inn at Narrow Passage

Inn at Narrow PassageIn March 1862, this inn served as Stonewall Jackson’s headquarters during his Shenandoah Valley Campaign. It was here that Jackson ordered Jedediah Hotchkiss to “make me a map of the valley.” (The extraordinary Hotchkiss maps are displayed in the Handley Library in Winchester.)

The inn wasn’t new then; it has been welcoming travelers for more than 250 years. The oldest part of the inn was built around 1740, and its sturdy log walls were protection from Indian attacks at the Great Wagon Road’s “narrow passage,” where the roadbed was only wide enough for one wagon to pass through. A large addition was made to the inn around the time of the Revolutionary War.

Innkeepers Ellen and Ed Markel Jr. welcome guests with lemonade served on the porch. Rooms in the older part have pine floors and stenciling. Rooms in the later additions also are decorated in the colonial style, but open to porches, with views of the Shenandoah River and the Massanutten Mountains. Most rooms have fireplaces. A hearty breakfast is served by the fireplace in the dining room.

Address: PO Box 608, Woodstock, VA 22664; tel. 540-459-8000; fax: 540-459-8001.

Accommodations: Thirteen rooms, all with private baths.

Amenities: Air-conditioning, parking onsite, room phones, fishing and hiking, conference facilities.

Rates: $$-$$$. Visa, MasterCard, and personal checks.

Restrictions: No pets, restricted smoking.

Ashton Country House

Ashton Country HouseAlthough Civil War artifacts have been unearthed near this inn, the town’s main link to the war was musical. It was the home of the Fifth Virginia Regimental Band, which Stonewall Jackson appropriated and rechristened the Stonewall Brigade Band. At Appomattox, Grant allowed the musicians to take home their instruments, and they serenaded him when he passed through town after the war.

This inn, an 1860 Victorian house, is a good place to relax, and Staunton (pronounced Stanton by the natives) is near a number of Civil War-related sites in the lower Shenandoah Valley, including the New Market Battlefield, the Lee Chapel, and Stonewall Jackson’s home in Lexington. The spacious house, furnished in the Empire style, has a forty-foot-long hall, high ceilings, and heart-of-pine floors. It is on twenty-five acres with goats and cows for neighbors. A secluded porch beckons those who just want to relax with a book. Hosts Vince and Dorie DiStefano greet guests with tea and home-baked goodies, and sherry and candy are placed in the guest rooms.

Address: 1205 Middlebrook Ave., Staunton, VA 24401; tel: 540-885-7819 or 800-296-7819.

Accommodations: Four double rooms, one suite, all with private baths.

Amenities: Central air-conditioning, off-street parking; TV, VCR, and fireplace in suite, fireplaces in three of the other rooms.

Rates: $$. Visa, MasterCard, and personal checks.

Restrictions: Children accepted with notice, no pets, no smoking.

Stonewall Jackson House

Stonewall Jackson HouseStonewall Jackson lived in Lexington and taught at the Virginia Military Institute during the 1850s. He and his second wife, Mary Anna Morrison, moved into this house in 1859, the only house he ever owned. After the war, the house was used as a hospital for a number of years before being opened to visitors. Now a National Historic Landmark, the house and garden have been restored to their appearance of 1859-61. A number of Jackson’s personal effects are on display in the house.

Jackson and hundreds of his compatriots are buried in the Stonewall Jackson Memorial Cemetery, on South Main St. The great general’s grave is marked by a full-length statue by Edward V. Valentine.

The Stonewall Jackson House, 8 E. Washington St., Lexington, VA 24450, is open Monday-Saturday, 9:00-5:00, to 6:00 in July and August, Sunday 1:00-5:00. Admission is $5 for adults, $2.50 for children six to twelve, free for children under six. Interpretive audiovisual program. Guided tours. For information phone 540-463-2552.

Virginia Military Institute

Virginia Military InstituteNext door to Washington and Lee University is the Virginia Military Institute, founded in 1839, the first state military college in the country. The school contributed a host of officers and men to the Confederate cause, including Lee’s most trusted lieutenant, Thomas “Stonewall” Jackson, who taught physics and artillery tactics here before the war. His statue now stands at the center of the campus, overlooking the parade ground, with the four cannons he named Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John. On the east side of the parade ground is Sir Moses Ezekiel’s seated statue of Virginia Mourning Her Dead, a monument to the ten VMI cadets who were killed in the 1864 Battle of New Market. Mementos of Jackson are on display in the campus museum, including the raincoat he was wearing when he was fatally shot at Chancellorsville. The bullet hole is clearly visible.

The Virginia Military Institute campus and museum are open daily except Thanksgiving and December 20-January 10. Admission is free. Dress parades are held Friday afternoons, September through May, weather permitting. For information phone 540-464-7000.

Llewellyn Lodge

Llewellyn LodgeCivil War buffs have a lot to see in Lexington—the Lee Chapel and the house Stonewall Jackson lived in when he taught at the Virginia Military Institute. And there are many antique shops to explore.

This handsome Colonial revival house has been a bed-and-breakfast since the early 1940s; in fact, it’s the oldest such establishment in town. Guests receive a warm welcome from hosts John and Ellen Roberts. In the summer expect lemonade or iced tea on the porch; in the winter it’s John’s “killer” hot chocolate or hot spiced cider by the fire and, of course, cookies. Ellen’s breakfasts are a local legend and John can lead you to the best trout streams and hiking trails in the area.

Address: 603 S. Main St., Lexington, VA 24450; tel: 540-463-3235 or 800-882-1145; fax: 540-464-3122; E-mail: LLL@rockbridge.net.

Accommodations: Six double rooms, all with private baths.

Amenities: Air-conditioning, off-street parking, public golf and tennis a mile away, fly-fishing nearby, concierge service.

Rates: $$. Senior discount, Monday-Thursday. All major credit cards and personál checks.

Restrictions: No children under ten, no pets, no smoking.

Lee Chapel

Lee ChapelRobert E. Lee was president of what now is Washington and Lee University. He assumed the position shortly after the war and served until his death five years later at the age of sixty-three. He was not simply a figurehead. He worked hard to lift the academic standards and increase the enrollment of the little college. His unpretentious office in the basement of the Lee Chapel on the campus remains intact, chairs still drawn up around a small conference table. Down the hall from the office Lee’s remains are entombed in a family crypt, and family mementos are displayed in a small museum. In the Chapel, upstairs, are hung the Pine portrait of Lee and the Peale portrait of the young George Washington, as well as the famous recumbent statue of Lee sculpted by Edward V. Valentine. Lee lies with one hand on his chest, his face tranquil but ravaged by the years of war. The remains of his beloved horse, Traveller, are buried outside the chapel. A few steps away from the chapel is the house where the Lees lived in those years.

The Lee Chapel is open Monday-Saturday, 9:00-4:00, Sunday, 2:00-5:00, except New Year’s Day, Thanksgiving, and the following Friday. Admission is free. For information phone 540-463-8400.

Red Shutter Farmhouse

Red Shutter FarmhouseOn May 15, 1864, a desperate General John Breckinridge ordered 247 cadets from the Virginia Military Institute to join the battle against the forces of Federal general Franz Sigel. The boys entered the fray fearlessly, and their heroism inspired the victory of the Confederate troops.

Five miles south of the battlefield, next to the Endless Caverns, is this friendly bed-and-breakfast on twenty acres, owned and hosted by George and Juanita Miller. The main house was built in 1790 and enlarged in 1870, 1920, and 1930. Guests are offered a variety of large rooms, all furnished in the Virginia country style.

Address: Rte. 1, PO Box 376, New Market, VA 22844; tel: 540-740-4281; fax: 540-740-4661.

Accommodations: Five double rooms, three with private baths.

Amenities: Air-conditioning, off-street parking, afternoon tea, TV and game room, hiking, nearby golf, horseback riding, antique and craft shops.

Rates: $$. Visa, MasterCard, and personal checks.

Restrictions: No pets, restricted smoking.

New Market Battlefield

New Market BattlefieldOn May 15, 1864, a large Federal force on its way to plunder the supply depot at Staunton was met by General John Breckinridge leading five thousand hastily assembled troops, including 247 cadets from the Virginia Military Institute. The outcome was in doubt until Breckinridge reluctantly ordered the cadets into battle. The boys charged the Federal line, making possible a Confederate victory.

The Hall of Valor here has exhibits tracing the events of the war, and audiovisual presentations on Jackson’s 1862 campaign and the VMI heroes. The New Market Battlefield Park and Hall of Valor are open daily. From I-81 take Exit 264 (New Market), go west on Rte. 211, then right on Collins Dr. (Rte. 305). Admission is $6 for adults, $5 for seniors, and $2 for children six to fifteen. For information phone 540-740-3101.

The New Market Battlefield Military Museum is on Manor’s Hill, where the fiercest fighting took place. Each side held a position on the hill until the Federals were forced to retreat north. The victory here was the last Confederate victory in the Shenandoah Valley. The museum has over three thousand artifacts ranging from the Revolutionary War to the Gulf War, with a focus on the Civil War. From I-81 take Exit 264 at New Market, turn west; turn right at next road (Collins Dr.). Travel a quarter of a mile. Museum entrance is on left at top of hill. A thirty-five-minute film on the war is shown hourly. Visitors can take a self-guided walking tour of the battlefield, following historical markers. Open March 15 through December 1, daily 9:00-5:00. Admission is $6 for adults, $5 for seniors, and $2 for children. For information phone 540-740-8065.

The Museum of the American Cavalry, 298 W. Old Crossroads, has an extensive collection of cavalry-related items: guns, sabers, and uniforms, with special emphasis on the Civil War. From I-81 take Exit 264 and turn west on Rte. 211, then make an immediate right onto Collins Dr. Museum is on the left. Open April through November, daily, 9:00-5:00. Admission is $4.50 for adults, $2.50 for children. For information phone 540-740-3959.

Chester

ChesterLate in the war, during Sheridan’s devastating Shenandoah Valley campaign, Major James Hill was wounded while commanding the local Confederate forces. While recuperating here at Chester, he was visited by General Sheridan and his aide, Colonel George Armstrong Custer. Believing Hill was a dying man, they decided not to arrest him. Hill fooled them, however, and lived to become a general and editor of the local newspaper after the war.

This beautiful house was built in 1847 by a retired landscape architect from Chester, England. Chester’s eight acres contain a lily pond, stands of English boxwood, and upward of fifty different varieties of shrubs and flowers.

Innkeepers Craig and Jean Stratton have given Chester an elegant charm that befits an English inn. Convenient to Jefferson’s Monticello, Monroe’s Ash Lawn, Michie Tavern, and the other attractions in the Charlottesville area, Chester provides an intimate setting for comfort and relaxation.

Address: 243 James River Rd., Scottsville, VA 24590; tel: 804-286-3960.

Accommodations: Five double rooms, all with private baths and fireplaces.

Amenities: Air-conditioning, off-street parking, bicycles on request, dinner at extra charge with advance notice for groups of six or more, fishing and canoeing available nearby.

Rates: $$$. Visa, MasterCard, and personal checks.

Restrictions: No children under eight, no pets, restricted smoking.

Appomattox Manor Plantation

Appomattox Manor PlantationFrom June 1864 until the end of the war, General Grant made his headquarters in this cabin on the lawn of Appomattox Manor Plantation, near the junction of the James and Appomattox Rivers. City Point became the center of the Union war effort during the Petersburg Campaign, and tents and cabins occupied nearly every available square foot of the plantation grounds. While Lee and his army suffered in the trenches before Petersburg, shiploads of food and supplies arrived daily for the Union forces. A special twenty-one-mile railroad was built and eighteen supply trains sped supplies to the front. The matériel pouring into City Point were a symbol of the Union’s great advantage in the war—it simply had more than enough of everything. President Lincoln visited City Point on two occasions, using the drawing room of Appomattox Manor as his office. He was here for two of the last three weeks of his life. His ship, the River Queen, was moored just offshore. A day after Lincoln left, Grant moved closer to the Petersburg front and began his final offensive.

Appomattox Manor Plantation, at the intersection of Cedar Lane and Pecan Ave., is now the City Point Unit of Petersburg National Battlefield (see this page). Two rooms at the Manor are open to the public, and General Grant’s cabin still stands on the grounds. A fifteen-minute video is available, and visitors can take a self-guided walking tour. Open daily, 8:30-4:30, except for federal holidays. Admission is free. For information phone 804-458-9504.

Lynchburg Mansion Inn

Lynchburg Mansion InnLee’s tattered army was headed for the railroad here at Lynchburg when it was cut off by Grant and forced to surrender at Appomattox, a half-hour’s drive away.

For a time before the war, Lynchburg was the second wealthiest city in America, and while the city has more than its share of grand mansions, none is grander than this one, once the home of self-made multimillionaire James R. Gilliam.

The beautiful columned house blends Spanish and Georgian elements, and each of its many rooms is a showcase. A large grand hall, with high ceilings and paneled wainscoting, opens onto a parlor furnished with Victorian antiques.

Innkeepers Bob and Mauranna Sherman have made sure that the guest rooms and suites are equally splendid. One of the suites opens onto a circular balcony. Morning begins with coffee and juice and a newspaper on a silver tray by your guest room door, a prelude to a gourmet breakfast that will see you through a morning of sightseeing.

Address: 405 Madison St., Lynchburg, VA 24504; tel: 804-528-5400 or 800-352-1195.

Accommodations: Five guest rooms, two of which are suites, all with private baths.

Amenities: Air-conditioning, off-street parking, fireplaces, hot tub on porch, library, garden with gazebo.

Rates: $$-$$$. All credit cards and personal checks.

Restrictions: No pets, no smoking.