Things I didn’t see coming

‘What are you doing here?’ I hissed at Trixie in the playground.

The entire school had been evacuated because of the fire alarm. Hundreds of students were hanging around on the football field, their teachers trying to get them into order. Mrs Dorbel was talking to the firefighters over by the road. She was waving her arms in the air and pointing towards our classroom, where smoke could still be seen pouring from the window. Her eyes flicked suspiciously across the mass of kids.

For the second time in as many days, the fire brigade had been called. First the public library, now the school.

‘I’m going to school! Do you like my uniform?’ Trixie said, giving a twirl. ‘I think I look kind of stupid. Brown and yellow are the worst colours. I can’t believe we have to wear this every day.’

‘You do not go to my school!’ I insisted.

‘Well, I have a uniform that says I do,’ she said, smiling. ‘I got it from lost property. Why would there be a school uniform in lost property? Is there some kid running around in the nude because they lost their uniform?’

‘I don’t know!’ I snapped. ‘Why are you here?’

Trixie sighed and rolled her eyes as if she was annoyed I wasn’t going along with her game.

‘I’m here to make sure you hang on to this,’ she said, handing me back my copy of the Encyclopedia of Amateur Magic. It was the one Mrs Dorbel had just locked in her desk. I could tell by the corners that I had folded over and the piece of gum that I’d stuck to the spine. That really would have annoyed Mum.

‘You stole it?’ I asked. ‘Again?’

‘I retrieved it,’ she corrected. ‘And a thank you wouldn’t go astray.’

‘Thank you . . .?’

‘You’re welcome,’ she said brightly.

‘For what?’

‘For getting you the book back.’

‘I didn’t ask you to do that.’

‘AND for getting you out of class.’

‘Getting me out of class?’

Then it hit me.

‘You,’ I exclaimed. ‘You started the fire in the rubbish bin.’

‘Shhhh!’ she hissed, looking around. ‘They were just a couple of smoke bombs. They were perfectly safe. I make them myself. You’ll never guess what the secret ingredient is.’

‘I don’t care—’

‘Ping-pong balls,’ she whispered, like it was a national secret. ‘Of course, you’ve got to use the right sort of ping-pong ball. The cheap plastic ones produce this really nasty gas.’

‘Why would you do that?’ I said. ‘You could have got in big trouble.’

‘I had to create a diversion so I could get that book back before Mrs Dorbel destroyed it. Hey, have you learned how to steal a watch yet?’

‘Hang on,’ I said. ‘Are you trying to tell me that you snuck into my school, put your name on the seating chart and set off smoke bombs just so you could make sure that I had a copy of a book?’

I was yelling now and more heads were turning. Gary wandered over.

‘Who’s this?’ he asked, looking at Trixie. ‘Is she the new girl?’

‘I’m Trixie,’ she said, holding out her hand for Gary to shake. ‘I’m a magician!’

Gary looked at Trixie’s hand.

‘Really? Did you teach Nick that card trick?’ he asked enthusiastically.

Trixie looked at me, surprised and a little pleased. She opened her mouth to speak.

‘She’s an exchange student,’ I blurted out, pushing her away from Gary. ‘From France.’

‘Et depuis le futur également,’ Trixie called out as I dragged her over to where the kindergarten kids were being organised into rows by their teachers. A few of them were crying from over-excitement or fear. Or just because they were little and, when you’re little, sometimes you just have to cry. Somewhere above me I could hear a plane in the sky. Its engine kept getting louder and softer, as if it was circling above us. Surely they hadn’t called in a plane just because of one little pretend fire?

‘What is going on?’ I said. ‘Who are you?’

The smile faded a little from Trixie’s face. ‘I can’t get into that here, but it’s super important that you read that book. Read it, learn the tricks, practise them. That’s all I can say.’

‘I don’t get it. What is so important about this book?’

‘It’s not the book that’s important,’ she explained, looking over her shoulder. ‘It’s you.’

And suddenly I got it.

She was nuts.

Because no one would ever call me important. I was just a kid whose mum was a librarian and whose dad was a geologist. I only knew how to do three tricks. I couldn’t even steal a watch and I had practised for at least twenty minutes.

‘Why don’t you just hang on to this,’ I said, pushing the book back into her hands. ‘I have to go . . . away.’

I turned and walked away. A few of the kids were nudging each other and pointing to the plane that was flying overhead.

‘Do you wanna see something cool?’ she said behind me.

I stopped and turned back. I was going to regret this.

‘What?’ I snapped.

‘Name a number,’ she said with a smile. ‘Any number.’

Now, here’s the thing about getting someone to think of a random number. People are kind of predictable.

If you ask someone to think of a number between one and four, the chances are they’ll say three. If you ask them to name a capital city in Europe, they’ll probably say London. Name a flower? Odds are they’ll pick a rose.

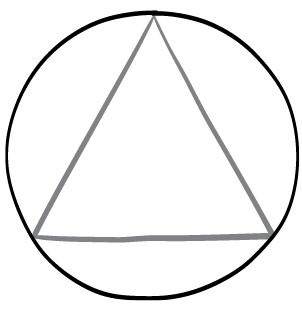

In fact, try this. Draw a triangle inside a circle on a piece of paper like this but don’t let anyone see it.

Now go up to a friend and say, ‘Can you draw a basic shape for me? Like a square?’ Chances are, they’ll draw a triangle or a circle. They won’t draw a square because you just said square.

If they draw a circle say, ‘Now draw another shape inside the first one.’

If they draw a triangle say, ‘Now draw another shape around the first one.’

Most of the time, you’ll end up with a shape just like the one above. If you do, show them what you drew and watch their brains explode.

If they ignore you and draw something completely different and wild just look at the shapes and say, ‘Ah yes, a hexagon inside a hyperboloid, interesting. I have just the trick for someone who thinks like you,’ and then just do another trick. They had no idea what you were planning anyway.

But Trixie had just asked me to name any number. And I wasn’t feeling particularly generous.

‘Fine,’ I said, pulling a number out of thin air. ‘Sixteen million, three hundred and twenty-six thousand, four hundred and six!’

The sound of the aircraft that had been circling us for the past five minutes was getting louder. Trixie smiled and pointed at it. I looked up and spotted the small red plane straight away. Behind it was a long banner fluttering in the wind. I squinted to read it. It was an eight-digit number.

Sixteen million, three hundred and twenty-six thousand, four hundred and six.

‘I hope you’re impressed,’ Trixie said as my jaw hung open. ‘Because that cost us a lot of money.’

‘How the heck—?’ I started.10 ‘The same way I knew you were going to be at the magic club last night,’ she said, ‘and the same way I knew to be in your class today. And that Mrs Dorbel was going to confiscate the book.’

She handed me the Encyclopedia of Amateur Magic.

‘I can predict the future.’

The plane was flying away now, the banner still flapping behind it. If there was another way she had done the trick I had just seen, I had no idea what it was. It was impossible.

‘You’re really magic?’ I said quietly, and Trixie burst out laughing.

‘What? No!’ she cackled. ‘You birdbrain.’

‘Didn’t your parents teach you not to call people birdbrain?’

She opened her mouth to say something then changed her mind. ‘I’ll tell you what,’ she said instead. ‘If you take that book and promise to learn everything you can, I’ll tell you how I can predict the future. Deal?’

I looked down at her outstretched hand. The fresh air must have been good for me because I was feeling much better. I looked around the field at the rabble of kids and teachers, the fire engines and the smoky school. Did I really want this kind of trouble? How desperately did I want to be a magician?

‘Deal,’ I said.

And we shook on it.