Amy Berman is a dedicated amateur artist and registered nurse who distributes health policy grants for the John A. Hartford Foundation in Manhattan. She loves to write, travel, surf, and spend time with her family, especially her grown daughter, Stephanie, with whom she shares a house in Brooklyn. One fall morning shortly after her fifty-first birthday, Amy stood in the shower and felt, on her right breast, a dimpled patch of skin the texture of orange peel and about the size of a nickel. A first round of tests revealed she had inflammatory breast cancer. Many early breast cancers are curable. But inflammatory breast cancer is a rare beast, infrequently found before it has spread.

At Maimonides Cancer Center in Brooklyn, she underwent a PET scan and a bone biopsy to explore a suspicious-looking area in her lower spine. She then scheduled a meeting with the nation’s top academic expert in her cancer, at his office in a university medical center in Philadelphia.

She and her mother, Rose, who joined her from Florida, checked into a hotel and went for a walk in the rain through a neighborhood of shuttered antiques shops. They were planning to meet friends for dinner and, after the doctor’s appointment the next day, go shopping for the wigs Amy would need when chemotherapy temporarily robbed her of her hair.

Amy’s cell phone rang. It was her oncologist at Maimonides, calling about the biopsy. Clusters of cancer cells had been found in Amy’s spine. She blurted out the news to her mother. They dropped their umbrellas and held each other as the rain poured down.

“I thought, in that moment, I have a very short life span,” Amy said. Her cancer had spread and would eventually kill her. Eleven to 20 percent of people with her diagnosis survive five years, and only a handful live more than seven.

Thoughts rushed through her brain. Who would guide her daughter after she was gone? How would she tell her sister, who was also her best friend? “I thought about what I was going to be giving up, about saying goodbye to people. It was a succession of overwhelmingly negative thoughts about what it means to have a terminal illness,” she said. “Looking into my mother’s eyes, I felt I had injured her heart, and that made me feel just that much worse.”

She and her mother returned to the hotel, where Amy caught a glimpse of herself and her mother in a lobby mirror. Their faces were distraught, blotchy, and red; their eyes puffy; their cheeks slicked with tears and rain. “Seeing how I was appearing to the world shocked me into thinking, I have decisions to make,” she said. “I turned to my mother and said, ‘We need to take three deep breaths.’ We took three deep breaths and burst out laughing.”

Amy said to her mother, “If I spend my remaining days mourning the cancer, the cancer wins. It will take away any goodness in my life, and I refuse to allow that to happen.”

They decided to go ahead and do what they would have done had there been no crisis. They returned to their rooms, put on fresh makeup, and went out to dinner with their friends. “It was a lighthearted dinner,” said Amy. “It set us on a path of living and not dying.”

The next morning, Amy told the famous oncologist about her biopsy results. He didn’t pause. “Here’s what we’re going to do,” he said, plowing ahead with his plan: six weeks of intense chemotherapy followed by surgery to remove her breast. Then radiation and another round of chemo.

Amy was being invited to play a role she didn’t relish—that of the unquestioning patient who heroically “battles” her disease to the end. The doctor’s aggressive, hail-Mary treatment plan would expose her to great suffering, and then she’d bump along—for who knew how long?—in severely damaged health. And for what? Her cancer couldn’t be rooted out. She questioned the unspoken assumption that the most harrowing treatment would produce the best possible result.

The interaction was one-sided and top-down. The oncologist asked no questions. He assumed that Amy cared mainly about attacking the cancer, no matter how devastating the collateral damage to her body and her life. It was her job, apparently, to participate in a common modern medical ritual: not to question why, just to do—and then die. “There was no conversation,” she said. “He was expert in everything but what really mattered to me. I thanked him for his time and left.” She returned to her cancer doctor at Maimonides and never went back to Philadelphia.

Amy opted for a different rite of passage: a quiet declaration of independence. As she went forward, her doctors would be her consultants, not her bosses. She would seek out those who were curious about what mattered to her and willing to shape their treatment plans accordingly. She would weigh her medical options in the light of their impact on what the poet Mary Oliver called “your one wild and precious life.” She would stay in the driver’s seat. It was her life and her death.

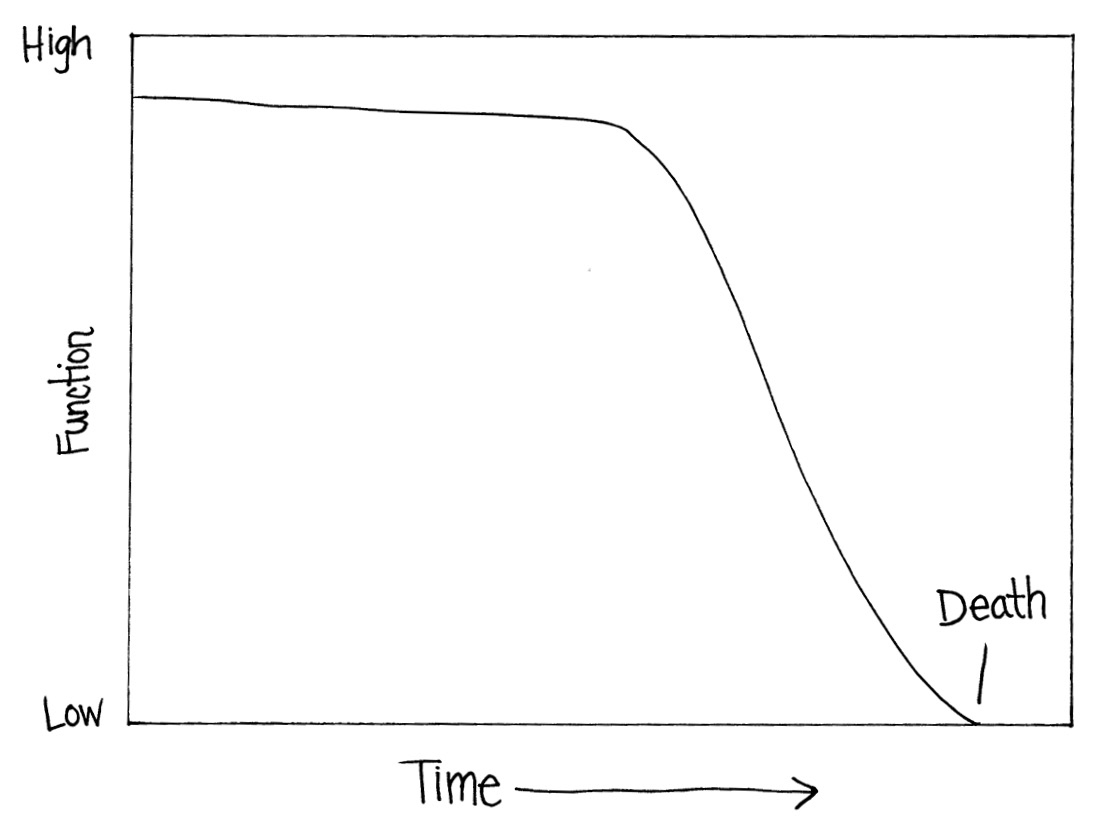

Back at Maimonides, her original oncologist asked a more welcome question: “What do you want to accomplish?” Amy said she hoped for “Niagara Falls” trajectory: to live well for as long as possible, and then to plunge over the waterfall to death without undue delay. The oncologist suggested she start with a daily pill of Femara, which inhibits the body’s production of estrogen, a stimulator of breast cancer growth. There would be no radiation, no chemo, and no mastectomy. The aim wasn’t cure. It was to slow Amy’s cancer while interfering as little as possible with her life.

It’s been seven years since Amy stood weeping with her mother in the rain. She knows her days are numbered and she accepts it. She remains on the top side of Niagara Falls. Femara held her cancer at bay for four years before, as expected, it stopped working. She’s now on a second estrogen-inhibiting pill, tamoxifen, which she expects to be effective for about half as long as Femara was. She takes another drug to keep her bones strong and to fend off the osteoporosis that is a by-product of tamoxifen. She finds other side effects—prematurely aging skin, energy loss after taking her pills at night, and high temperatures that feel like sustained hot flashes—acceptable in light of her hunger for continued life.

She’s never spent an afternoon in a recliner while a toxic chemotherapy dripped into her veins. She’s never been hospitalized, or been too weak to drive, or needed a home health aide. Her hair hasn’t fallen out. She hasn’t gone into debt. She has climbed the Great Wall of China, ridden a jet ski to the base of the Statue of Liberty, and seen her daughter, Stephanie, graduate from college and get married. She has made quality of life her priority, and paradoxically she’s outlived many people who opt for more grueling treatments. “Most doctors,” she says, “focus only on length of life. That’s not my only metric.”

We are all mortal. But knowing this abstractly and feeling it viscerally are not the same. The bad news may arrive as a stunning diagnosis, or more ambiguously and unpredictably, as a vital organ slowly fails. Sometimes incurable illnesses (and their treatments) create long periods of disability, necessitating immediate plans to get caregivers and support teams in place. Others permit months to years of continued high functioning.

People who do well in this health stage have usually mastered the tricky art of accepting death while continuing to live. They decide what matters to them and make their medical choices according to their own lights. They do what they love. They expand the boundaries of the word “hope” to encompass miracles beyond cure, such as family reconciliation, leaving their survivors in good shape, or taking the grandkids on one last memorable trip to Disneyland. They often get support from a relatively new medical specialty: palliative care. This misunderstood approach focuses on relieving suffering, improving day-to-day well-being and functioning, and helping patients make medical choices in alignment with what matters most to them.

In modern health care, doctors sometimes deliver bad news and then barely pause before proposing (or simply informing you of) their plan for your treatment. I suggest you stop and take a breath after receiving a tough diagnosis. Most forms of modern death move slowly. There is no harm in taking a few days to tend to the soul, to let awareness sink in, to talk with friends, and to gather information before deciding how you want to proceed. Going forward you will need clear information, support in grieving your losses, and time to reflect on new ways to define hope.

“You almost become numb,” said Ron Belcher, who was seventy-two and had severe congestive heart failure when he was told that his colonoscopy had revealed early signs of colon cancer. Much to his surprise, his surgeon bluntly recommended against surgery. His cancer, she said, was slow-growing; he was more likely to die with it than of it. Given the stress of the operation and the severity of his heart problems, she said, he had a 90 percent chance of dying within two months if he had surgery.

“You say to yourself, okay, I gotta process this, but I can’t process this right now,” Ron said. “I’m in front of a group of doctors and a daughter-in-law who’s also had cancer. I’ve got to go home and meditate, think about this in private, mull my options, and cry if I need to cry.” Ron took a week to discuss the pros and cons with his family and decided against surgery. “I appreciated that my surgeon didn’t beat around the bush,” he said, “but it was the most gut-wrenching decision I ever had to make.”

Find people capable of listening to you without judgment—be it a friend, relative, or hospital social worker or chaplain. Most health systems offer support groups for people with terminal illnesses, and there you may find a welcoming community that can address every dimension of your experience—not just your medical decisions, but your emotional, practical, and spiritual concerns. People who go to support groups tend to be less stressed and better informed than those who don’t attend them, and sometimes they live longer.

After awareness and acceptance comes action. When you feel capable, it’s time to hold an honest, difficult, conversation with your doctor. These talks can be so painful that most doctors and patients simply don’t have them. But they are vital if you want to lay continued claim to your life and your death. Ariadne Labs in Boston, founded by the surgeon-author Atul Gawande, is doing the critical work of training doctors in how to hold these conversations, as is oncologist Anthony Back, of the University of Washington, at Vitaltalk. But until training improves, “physicians are waiting for the patient to bring things up and patients are waiting for the physicians to bring them up,” says Alvin H. “Woody” Moss, MD, a kidney specialist and palliative care doctor at the University of West Virginia’s medical school. “There’s a conspiracy of silence.” Break it.

In one study of patients with fatal lung cancers, half hadn’t discussed hospice with their doctors two months before their deaths, and in another, three-quarters of patients with incurable, metastatic lung cancer had the mistaken impression that cure was possible. As Moss puts it bluntly, “Doctors usually sugarcoat how bad things are.”

If you can, bring a friend or relative to the meeting to provide emotional support, take notes, and ask follow-up questions. Amy Berman recommends that you open with some version of “I want a realistic picture, so I can plan.” If the answers you get are filled with incomprehensible medicalese, I suggest you try some version of “I don’t understand. Would you say that again, more simply?” And if you get a clear answer, it’s great to say, “Thank you, that is exactly what I was looking for!”

Some physicians worry that telling you the truth will take away your hope. But knowledge is empowering. People with a clear understanding of the courses of their illnesses tend to do as well or better physically than those kept in the dark, and they don’t suffer any more or less emotional distress. “Some people don’t want to know what the future holds,” says Ron Hoffman, the founder of Compassionate Care ALS (Lou Gehrig’s disease) in Falmouth, Massachusetts, who has supported hundreds of people through the last stages of their lives. “But on the whole, those who are willing to explore and navigate the terrain of their mortality have more peaceful, gentle, and even beautiful deaths.”

Some people get angry when their doctors deliver bad news bluntly. But consider, for a moment, the alternative. One nurse, assigned to improve treatment of the terminally ill in her large health system’s emergency rooms, told me of encountering “staggering numbers of patients with devastating symptoms of stage four cancers who were told they were dying by [an emergency room] physician who did not know them.” They were shocked by the news and sent home to die under hospice care, making it unlikely they’d ever again see, or say goodbye to, the oncologist with whom they’d developed a trusting relationship.

“These patients often feel abandoned at their greatest moment of need,” she went on. “But we have not been successful in working with the oncologists to have honest discussions earlier, because the oncologists tell us their patients fire them if they are truthful.”

Go ahead and ask. Make sure you understand the trajectory of your illness if it follows its usual course. If you have cancer, get clear on its stage and its type in the context of your age and overall health, which will shape your trajectory. Some cancers are curable and others, including almost all stage four cancers (despite recent advances in immunotherapy) are not. Some move slowly and, with treatment, permit years of high functioning, and others usually kill within a year. Precise predictions of the time you have left are rarely accurate, and doctors, on average, overestimate their patients’ survival time by four to six times. You can, however, get a rough estimate of whether you have “days, weeks, months, or years.” That is meaningful enough to frame your choices.

Take a step further. Ask not only about length of life, but about how you will feel and function, and how proposed treatments may affect your well-being. You may need to find caregivers or a health care agent, to sign an advance directive, to buy adaptive equipment, or to apply for Social Security disability or other public benefits. You may choose to say no to drugs and procedures with severe side effects and dubious payoffs. Or, if you know that a treatment will be debilitating, you may seize the bittersweet gift of time to first take a photography class or visit relatives, or to reconcile with an estranged family member.

Improving your understanding and command of the situation can reduce feelings of helplessness, and give people who love you specific ways to help. If your doctor refuses to discuss your prognosis at all—and some do—consider that a warning sign. You are unlikely to feel empowered if you are left in the dark. If, after a try or two, you still have only the foggiest picture, I suggest you find a new specialist who is more forthcoming, or add a palliative care doctor to your team, as explained on page 90. As a supplement, the American Cancer Society offers accurate information online, and so does the Mayo Clinic. (Beware, however, of sites primarily funded by pharmaceutical companies and others that are trying to sell you something.)

Many people find that a pen-and-paper sketch helps them visualize what the future holds. Below are four common trajectories to the end of life. Three of them (Niagara Falls, Looping Decline, and The Dwindles) were first formulated in 2005 by the pioneering geriatrician Joanne Lynn and were included in 2014 in Atul Gawande’s bestselling book Being Mortal. The stair step pathway was first sketched for me by a counselor for the Alzheimer’s Association.

You might ask your doctor which best fits your situation, and if none do, ask him or her to draw you another.

The Niagara Falls Trajectory

This pathway is marked by months to years of high functioning, followed by a rapid decline of a few weeks or months. It is common in kidney failure without dialysis and in cancers treated once or twice. When symptoms are well managed, thanks to palliative care or hospice programs, people often can continue to work, do things they enjoy, and even go out for coffee with friends until a few weeks before death.

Looping Decline

Repeated health crises land people in the hospital, where they recover somewhat and return home, only to decline until the next crisis. It’s hard to precisely predict death, as there’s no way of knowing which hospitalization will turn out to be the final one. This trajectory is common during the failure of vital organs, in heart and lung diseases that often strike in the seventies and eighties, and in cancers at any age treated repeatedly with chemotherapy and radiation with strong side effects. People need help with daily chores, at first occasionally and then frequently. Some crises can be averted with physician house calls and close medical management. Death sometimes comes after a final catastrophe, and sometimes after a patient tires of repeated treatment or says something like “no more hospitals.”

Stair Step Down

Long and short plateaus are punctuated by sudden, drastic drops in functioning. Each “new normal” is worse than the one before. This pattern is common in people who have repeated strokes or vascular dementia, and in the old and frail who undergo repeated hospitalizations that set off delirium (hallucinations and prolonged cognitive confusion) or otherwise inadvertently cause harm.

Strength and vitality fade away, along with appetite and interest in living. Small maladies accumulate, senses fail, muscles weaken, and over time the body just wears out. The need for help with daily life may last as long as a decade. This trajectory is common in dementia, extreme old age, and kidney failure with dialysis. Medical decisions often fall to family members. Death sometimes comes naturally and gently, or after a decision to forgo antibiotics or otherwise let nature take its course. At other times, death arrives in the form of a pneumonia, a broken hip, or an infection that would not have vanquished a hardier person.

Share your sketches with your family. It takes time for people to absorb the notion that you will die someday, and the unprepared can wreak havoc at the end of life. Keep talking until everyone accepts the truth. Doctors say that it’s often a conflicted family member who insists on risky, last-ditch treatments. The doctors go along because they fear lawsuits, complaints, and bad professional reviews. “I can’t begin to tell you the times I did not want to operate on someone because it was futile or because the quality of their remaining time would greatly suffer,” one surgeon told me. “But the family were absolutely dead set and insisted on ‘everything being done.’

“Sure, I could refuse and recommend they find another doctor, but if the patient dies in the meantime, I come under fire and ‘review’ even if I believe that not intervening is the right thing. If a family even tries to file a lawsuit, it stays with a physician’s record.” So she reluctantly performs Hail Mary surgeries after, as she puts it, “covering my butt” by thoroughly documenting that she has disclosed the risks. This sometimes ends with watching a patient die a horrible death, sedated and on a ventilator. “It’s painful for me to see and experience this,” she said, “since I am part of why (despite not wanting to be) the patient is not having a dignified death.”

Once you understand the general contours of what you’re facing, I recommend you add a palliative care doctor to your team. Many people have never heard of palliative care, or else confuse it with hospice, but don’t let that stop you. (Briefly, hospice is for people likely to die within six months, while palliative care is helpful much earlier in the course of a long illness.) Every dimension of your experience will probably be easier with this extra layer of support.

Palliative care focuses primarily on relieving suffering and improving function, not on curing disease. The word “palliative” has been a recognized part of medicine since at least 1543, when the first English translation of an earlier treatise by the Venetian doctor Giovanni da Vigo appeared, recommending “apalliating” incurable illnesses by “gentle remedies” rather than attacking a disease at its root. It became a distinct medical specialty in the 1970s, when other branches of medicine started to focus almost exclusively on prolonging life. It has become the preeminent medical ally for anyone who wants to live a good life while coping with a debilitating illness.

In some health systems palliative care is called prehospice, supportive care, pain management, symptom management, comfort care, or serious or advanced illness management. No matter what it’s called, you should ask for it: palliative care improves well-being and survival times so significantly that both the American Heart Association and the American Society of Clinical Oncology recommend it as early as possible.

Unlike hospice, which is usually reimbursed by insurance only when people abandon all attempts at cure and are within six months of dying, you can get palliative care while you are still fighting disease and hope to live much longer. Its doctors and nurses will work alongside your cure-oriented specialists. Like physical and occupational therapists, they won’t focus so much on “what’s the matter with you.” Instead, they will ask “what matters to you” and help you achieve it. They are experts at managing fatigue, nausea, anxiety, and breathlessness. They also step in as truth-tellers, counselors, and medical-decision coaches when other doctors feel unequipped to play those roles. They are not afraid to talk frankly about the realities of death and disability, and to help you prepare for them emotionally and practically. And because they work in teams and focus on the needs of the whole person, they often save people from falling through the cracks in fragmented health systems.

Recent research has shown that people who get palliative care have fewer health crises and spend less time in hospitals, and are therefore less often exposed to medical errors and infections. They die in hospitals less frequently, and enroll in hospice earlier. They experience less pain and suffering and they tend to leave their survivors in greater emotional peace. And oddly enough, they often live longer than people who continue with harsh, last-ditch, supposedly life-prolonging treatments.

Palliative care saved Amy Berman a great deal of unnecessary suffering when she developed excruciating pain in her back, four years after her cancer diagnosis. Cancer cells had migrated from her spine to her lower ribs, inflaming nerve endings. The standard treatment was ten to twenty doses of radiation, administered once a day for two to four weeks. The predicted side effects included exhaustion, hair loss, blistered skin, nerve damage, and a temporarily weakened immune system.

Before proceeding, Amy consulted with a palliative care specialist at Maimonides to weigh her pros, cons, and alternatives. Together they found studies showing that a single carefully focused burst of more intense radiation would work as well as multiple weaker blasts. That’s what Amy chose—after a struggle with her insurance company, which at first didn’t want to pay for the expensive scan necessary to deliver the radiation safely. Her back pain disappeared in one day, saving her pain, lost work time, and hundreds if not thousands of dollars in insurance co-pays.

A palliative care doctor helped Jerry Romano, a textbook editor in Menlo Park, California, who had to retire in his sixties after a heart attack and open-heart surgery. By the time he turned seventy, his heart problems had become so bad that his cardiologist arranged for an implanted defibrillator. Sometimes called “an emergency room in your chest,” defibrillators deliver massive and painful shocks to the heart to “reboot” it if it starts beating so erratically that life is threatened. (Less intrusive pacemakers, by contrast, keep hearts beating at a healthy, regular rhythm by delivering consistent, tiny electric pulses that are imperceptible to the patient.) The device did nothing for Jerry’s symptoms, chest pain and breathlessness, which kept him from doing what gave his life meaning—making beautiful painted wooden airplanes and toys for children in his backyard woodshop. Tired of a life that had lost its savor, he asked to have his defibrillator deactivated. After this was done, a palliative care doctor put him on oxygen at night (relieving his breathlessness) and adjusted his medications (easing his chest pain). He returned to his woodshop to build toys, and once again he felt life was worth living.

If your specialist balks and says it’s “too early” for a referral to palliative care (unfortunately this is still a common response) please note that in some health systems, you can call the palliative care department directly without a doctor’s referral. Some hospices also provide palliative care, and they can often help you find practitioners who provide it, as can the website getpalliativecare.org.

If you can’t find palliative care, do what its doctors would do: make sure you articulate what makes your life worth living, and see that the treatment you get serves those goals. “Do you like to go to the opera?” asks Dawn Gross, MD, a palliative care specialist at the University of California medical school in San Francisco. “Do you want to be able to garden, or sing, or play the piano, do the crossword puzzle, ski, go shopping, or be able to eat or talk to your grandkids?” Know what gives you joy, and let your doctors know, at every visit, whether you can still do it.

“A doctor will not be thinking in terms of whether you can garden,” Gross said. “They’ll just be thinking, ‘I’m going to do whatever I can to slow this down and come as close to curing it as I can.’ If you don’t have a really good footing, you will get sucked into a powerful current within medicine that assumes that you want to try to live forever, no matter what.”

At each visit, remind your doctor (and perhaps yourself) what matters to you. “When a patient tells me that they were able to paint or make the bed, that’s incredibly helpful to me,” says Anthony Back, a leading oncologist at the University of Washington who helped found a program called Vitaltalk, which trains oncologists in how to hold meaningful conversations with patients. “It’s very different from reporting your symptoms on a ten-point scale.”

Finally, address your fears. Ask your doctor:

• What is it like to die of my disease, and how can medicine ease my symptoms?

• Will you still be my doctor if I decide to opt for strictly palliative care?

• When do patients with my disease benefit most from enrolling in hospice?

Don’t let the business of medicine eclipse the business of living. Spend your limited energy and time on things that matter to you. To that end, feel free to turn down tests, treatments, and doctor’s visits that don’t serve your purposes. Dr. Back suggests asking your doctor, “How is this test going to change what we’re doing—or are we just doing it for more information? If that’s the case, I’d just as soon skip it.”

You have no obligation to create a voluminous medical history or to monitor a condition that can’t be cured. Shrinking a tumor or stopping it from growing sounds good. But oddly enough, tumor shrinkage in and of itself doesn’t predict an extended life span or improved day-to-day well-being. Between 2004 and 2014, about 74 percent of cancer drugs approved by the FDA as “effective” because they arrested tumor growth did not improve patient’s survival time by a single day. (Ask, instead, if the treatment is “clinically effective,” meaning that it actually benefits patients.) Resist focusing on repeated scans, and check in with your own body. How well you feel, and how much or little you can do, are more meaningful measures of your health and better predictors of what your future holds.

Don’t, by the way, place much stock in media hype about breakthroughs around the corner. They’ve been appearing regularly for half a century. Take for instance, recent advances in immunotherapy for cancer. A small group of people get an extended plateau, but immunotherapy is not, so far, a cure. What is rarely discussed is that after a “honeymoon period” when tumors melt away, the cancer usually returns. Overall time gained is often limited to a few months, and the treatment’s suppression of the immune system produces terrible side effects that can be health-destroying and even life-ending.

Some treatments forestall death for years with relatively gentle side effects. Others delay death without restoring health. Still others are triple losers: they damage the quality of remaining life, they reduce its length, and they cost a fortune in co-pays. This medical labyrinth is confusing even to people, like Amy Berman, with substantial medical training.

As a guide to this confusing environment, keep in mind the law of diminishing returns. If your disease is terminal, each successive round of treatment is likely to produce fewer gains, and to work for a shorter time, than the one before it. This is especially true if you are growing weaker. In lung cancer, average survival time is four months after a third “line,” or round of treatment. The fourth line produces no better results than no treatment at all and, in the words of oncologist and palliative care doctor Thomas Smith of Johns Hopkins, is “ineffective, toxic, and delays hospice use.”

Therefore, keep making sure you understand how your life, functioning, and well-being will be affected by a demanding treatment, be it repeated chemotherapy, an external heart pump, or dialysis. Many of these are called “halfway technologies” because they ward off death without restoring health. They often place massive burdens on caregivers and substantially damage the quality of remaining life. Just because a doctor offers something, and insurance will pay for it, doesn’t make it a good idea. Sometimes doctors are secretly relieved when patients reject a harrowing treatment with minimal payoffs that they felt duty bound to offer. You are not required, legally or morally, to agree to any procedure you don’t want. Most people believe that there are fates worse than death, and it’s up to you to decide where you draw that line.

As you proceed, keep making sure that you and your doctor remain on the same page. Each time a new treatment is proposed, ask your doctor what he or she hopes to accomplish. As a reminder, the five traditional duties of medicine are: to prevent disease; to restore functioning; to prolong life; to relieve suffering; and to attend the dying. Sometimes these goals are in sync; toward the end of life they can be at cross-purposes. Which goal is your doctor trying to fulfill? Ask: “Do you hope this will give me more time? Cure my disease, or slow it down? Improve how I feel or function day to day?” Then think through whether these priorities match your own, and whether the trade-offs are worthwhile to you.

It may help you retain your agency and your moral authority if you understand that financial incentives, hidden from your view, promote overtreatment. The pharmaceutical industry alone has more than three thousand lobbyists in Washington who shape health policy to their clients’ advantages. Few people with cancer know, for instance, that oncologists get more than half of their revenue from markups (in 2017, of 4.3 percent) that they are allowed to add to the price of the chemotherapy drugs they prescribe and administer. This funding system, known as “buy and bill,” creates an unfortunate incentive to prescribe the most expensive chemo and to infuse it long after it stops being helpful. This peculiar system underpays oncologists for making time for difficult conversations, and puts them all in a terrible bind.

So stay in the driver’s seat. Make the best decisions you can in light of uncertainty and your gut sense of what you can tolerate. “I’ve been in many support groups through the years,” said Merijane Block, who lived for two decades with a slow-moving metastatic breast cancer that eventually spread to her spine. “I’ve seen women who did everything . . . and they died. I’ve known women who couldn’t bring themselves to do everything . . . and they died. It’s one big crapshoot.”

Merijane underwent radiation, surgeries, and drug treatments. But for twenty years, she refused chemotherapies that would have been infused directly into her bloodstream and damaged noncancerous tissues in her skin, hair, and bone marrow. “I just couldn’t take a medicine that destroys healthy cells and causes so much devastation,” she said. “I had a very strong feeling it would kill either my body or my soul.”

Over time her cancer, in tandem with the radiation she was given to slow its progress, left Merijane in chronic pain. She used a walker and then a wheelchair. “The days of the somewhat-easier drugs appear to be over for me,” she said. Fearing the prospect of a painful, drawn-out death, she met with a palliative care doctor at her medical center.

He coached her on how to have a frank talk with her oncologist, a “brilliant clinician” with whom Merijane had bonded, but found intimidating. At their next meeting, Merijane put her hand on top of her oncologist’s hand and said to her gently, “The time is going to come when I’m going to shift to strictly palliative care. Will you still be able to be my doctor?” The oncologist’s eyes filled with tears. She said, “I’ll be with you till the end,” and both women began crying.

When a disease continues to advance, some people pin their hopes on becoming an experimental subject in a clinical trial of an untested drug. I suggest that before you enter a “stage one clinical trial,” you think hard about your motives. Some people find meaning in contributing to scientific knowledge before they die, and that is an achievable goal. But being a guinea pig in a clinical trial is a gamble with miniscule odds of improving your health or extending your life.

Consider the statistics. The FDA never approves 95 percent of untested cancer drugs that begin clinical trials, because they prove to be either dangerous, or ineffective, or both. According to a groundbreaking study in the New England Journal of Medicine, only 5 percent of volunteer subjects gained more time. Of those who did, half (2.5 percent of the total) lived less than an additional six months, and there are no good studies assessing the quality of that time. Some participants suffer side effects so severe that they drop out of the study or die sooner, with more suffering, than they would have otherwise. This dismal record recently led the medical ethicist Jonathan Kimmelman to write, in the Journal of Clinical Oncology, that it was time to deflate “the unscrupulous marketing of unproven interventions to desperate patients.”

So think through what a clinical trial asks of you. When time is short, do you want to spend it at clinic appointments? “Energy is your most precious commodity,” says oncologist Anthony Back. “Think about where you want to spend it. People think of clinical trials as risk-free lottery tickets, but they have their price.”

For some people, throwing “everything but the kitchen sink” at a fatal illness has become a medical rite of passage. In the words of the noted cancer researcher and physician Siddhartha Mukherjee, author of The Emperor of All Maladies, this approach can lead to “a scorched-earth operation with many long-term consequences.” There’s an unspoken belief, widely held among patients and doctors, that the more tests, procedures, specialists, treatments, and hospital visits you undergo, the longer and better you will live. But it can be just the opposite. For both the fragile and the relatively robust in their last months of living with cancer, new research is strongly suggesting that more chemotherapy frequently shortens life and contributes to a worse quality of death.

Much scientific research investigates treatments that attack diseases head-on. Less research explores how the body fights off disease. Cancerous tumors, Mukherjee notes, shed thousands of cells into the bloodstream daily, but only in some people do those cells develop into metastases. I encourage you to explore the many low-cost, low-risk ways you can strengthen your immune system, your first line of defense. They might improve how you feel and function today and are unlikely to do you harm. I’m not suggesting that you substitute carrot juice for a lumpectomy if you have a treatable breast cancer, but simply that you honor the capacity of your body, and your mind, to contribute to your healing.

Studies observing large groups of patients suggest that people with life-limiting illnesses who exercise, adopt a healthy diet, and get emotional support—as a complement, not a substitute, for conventional medicine—tend to live longer. A protein-sparing vegan diet can slow kidney failure. People with high bloodstream levels of vitamin D tend to do better after treatment for colon cancer. So do those adopting a so-called non-Western diet like the Mediterranean Diet, substituting vegetables, whole grains, olive oil, fish, and fruit for red meat, sugar, white bread, and other heavily processed “food products.” Acupuncture can reduce all sorts of pain. Stick with complementary remedies that are gentle, unlikely to hurt you, and may prove helpful. Most will not be reimbursed by Medicare or other insurance.

Marijuana for medical purposes, now legal in twenty-nine states, has been used in the West since at least 1850, when Ada Lovelace, the pioneering English mathematician and daughter of Lord Byron, used it to relieve the pain of her terminal cancer. Some palliative care physicians prescribe marijuana extracts containing high levels of THC (tetrahydrocannabinol) and say they improve appetite, and control pain and nausea better, than prescription pharmaceuticals—with the enjoyable side effect of euphoria. Hemp-derived oils saturated with the more staid psychoactive compound CBD or cannabidiol (a less mind-bending component of marijuana and hemp which is not on the federal government’s list of controlled substances) are widely available online without prescription. CBD is reported to relieve pain and anxiety without producing the euphoria of THC, but it doesn’t improve appetite.

“I am not a huge fan of hope,” says oncologist Tony Back. He urges his patients not to concentrate so hard on hopes that they forget about today. “A lot of people want to finish something,” he says. “They want to end up in some kind of peace, or to reconnect with people in some way. If only they could orient themselves to enjoy what is happening in the moment!” He also urges them to think about this question: “What is something you could do today that you could really enjoy?”

Below are some hopes, and some rites of passage, to consider, in place of a futile war on death:

Leave a good emotional legacy. In anticipation of death, some people write “legacy letters” to their children and grandchildren, describing what life has taught them. Others write milestone letters for daughters and sons to open on the day of a college graduation or wedding. “To be there when a son or daughter has a first child—that may not be an achievable goal,” says Shoshana Helman, a palliative care doctor at Kaiser Permanente in Redwood City, California. “But writing a letter that can be opened at that time is achievable.”

Enjoy the time you have left. When Ted Marshall, a fine carpenter trained in traditional Japanese joinery, learned he had the deadly brain tumor glioblastoma, he and his wife, Sharry, threw everything possible into the path of his cancer: surgery, radiation, conventional chemotherapies and off-label drugs, oriental medicine, a low-carbohydrate diet, a skull cap that zaps tumors with electrical currents, and blue scorpion venom from Cuba.

They also talked openly about how they wanted to live if Ted had six months to two years left. Sharry wanted him to be as happy as possible. Ted wanted to finish renovating the apartment they’d bought in a cooperative housing community in Richmond, California, so that he’d leave Sharry housed and in good financial shape.

The couple took as their motto “Don’t postpone joy.” In the first year, they went to a cowboy poetry gathering in Elko, Nevada; a fiddle festival in Port Townsend, Washington; and American “roots music” gatherings in Asheville, North Carolina, and Clifftop, West Virginia. After their return, Ted finished remodeling the couple’s home with the help of friends. “We did a good job,” Sharry said, “of wringing every drop of fun we could out of the life he had left.”

Over the next three years, Ted gradually lost the ability to spell, to work, to drive, and to remember to close the refrigerator. Nothing about it was easy, but he died peacefully at the age of sixty-eight, under hospice care, in the couple’s beautifully renovated, mortgage-free home.

Go on an adventure. Norma Jean Bauerschmidt, a retired nurse of ninety living in Presque Isle, Michigan, refused a hysterectomy and chemotherapy after learning she had stage four uterine cancer. She declined to enter a nursing home and instead moved into an RV with her son and daughter-in-law. The trio spent a year visiting national parks, with Norma moving about at first on foot, then in a wheelchair, and ultimately with the help of an oxygen tank. Instead of undergoing CAT scans, Norma got her first pedicure, mounted a horse, and rode in a hot-air balloon.

A month before her death, her son parked the RV on a friend’s land in Friday Harbor, on Whidbey Island off the coast of Seattle, and Norma enrolled in hospice care. She was ninety-one when she died, thirteen months after setting out on the road.

Leave loved ones in good shape. Amy Berman and her daughter, Stephanie, have updated the house they share, choosing paint colors and finishes in Stephanie’s taste—“so it can feel like hers when I’m gone,” as Amy said. Her daughter currently writes the checks for the household bills, so she won’t be at sea after her mother dies. Mother and daughter frequently get together with extended family, to ensure that Stephanie will feel known, protected, and loved in the future.

Amy keeps a notebook with detailed information about how to handle her finances and run the household when she is alive but no longer able to manage. She’s written notes about her gravesite, whom to call after she dies, and even where to order the food for the gathering after her memorial service. Her bank account will roll over to Stephanie automatically on her death, and so will her 401K.

“These acts may sound mundane but they are all deep acts of acceptance of my mortality and my focus on those I will leave behind,” Amy said. “They’re selfless acts of love, even if they seem trivial.”

Amy doesn’t have strong preferences for her funeral, as she thinks its purpose is to comfort the living. But she expects that her daughter will follow traditional Jewish mourning rituals, beginning with sitting shiva—staying home with mirrors covered and a candle burning for seven days while receiving visits from friends who bring food and share memories of her mother. Stephanie will recite the mourners kaddish, a short daily prayer glorifying God, for eleven months. On the one-year anniversary of Amy’s death, and every year thereafter, Stephanie will light a yahrzeit anniversary candle, which will burn for twenty-four hours before the flame dies out. Also on the first anniversary, Amy said, “My daughter will do an unveiling of my headstone as the closure on her grieving. When she visits my grave in future years, she will find a stone to leave on my headstone.”

All that is in the future. For the present, Amy says, “I don’t think about myself as dying. I am living until proven otherwise and I choose to live fully.” You don’t need a fatal diagnosis to live with this double awareness.