JOMINI AND CLAUSEWITZ IN HARMONY

CHRONOLOGY

| Dec 1804 | Napoleon crowned himself emperor of France. Spain declared war on Great Britain. |

| Aug 1805 | Austria, Russia, and Great Britain form the Third Coalition against France. |

| Aug 26 | The Grande Armée began to depart its cantonments along the English Channel and marched to the east. |

| Sep 24 | The Grande Armée arrived along the Rhine. |

| Oct 21 | Mack surrendered Austrian army at Ulm to Napoleon Nelson defeated Franco-Spanish fleet at Trafalgar. |

| Dec 2 | Napoleon defeated Austrian and Russian forces at Austerlitz. |

| Oct 8, 1806 | Prussia declared war on France; War of the Fourth Coalition began. |

| Oct 14, 1806 | French armies defeated Prussian armies at Jena and Auerstadt. |

| Oct 25 | French troops under Marshal Davout entered Berlin. |

| Nov 28 | Napoleon entered Warsaw. |

| Feb 7–8, 1807 | Napoleon fought to a standstill at Eylau by Russians and Prussians. |

| Jun 14 | Napoleon defeated Russian army at Friedland. |

| July 7 | Treaty of Tilsit between French and Russian Empires brought general peace to continental Europe. |

We owe it to Napoleon…that we now confront a succession of a few warlike centuries that have no parallel in history…we have entered the classical age of war, of scientific and at the same time popular war on the largest scale (in weapons, talents, and discipline). All coming centuries will look back on it with envy and awe for its perfection.

Frederich Nietzsche1

This chapter examines the period of Napoleon’s most dazzling campaigns with an instrument of war that bore little resemblance to anything that preceded it: the Grande Armée. The three continental campaign wars from 1805 to 1807 highlight the ascendancy of the French on land in the face of established British command of the seas. This period also illustrates the asymmetry of French arms against all other opponents as reflected in the brilliant campaigns of Ulm-Austerlitz, Prussia, in 1806, and the less brilliant, but victorious, campaigns in Poland in 1807 against the Prussian and Russian armies. The operational aspects of the writings of Jomini and Clausewitz owe much to this period of Napoleon’s military ascendancy. Jomini is the apostle of the offensive and these campaigns were primary evidence for his position. At the same time, Clausewitz advances the notion of a form of war that approaches the “absolute” in actual execution and these campaigns also support this idea. We also find a third party, Frederich Nietzsche from a less optimistic age, commenting, as did both Clausewitz and Jomini in their way, on the awesome, terrible “perfection” of war as was practiced by Napoleon in these campaigns. All three men saw in these events the operational shape of things to come.

* * *

From 1803 to 1805, France and Britain fought a maritime war. By late 1804, however, the winds of war on the continent again began to blow. Tolstoy’s opening line from War and Peace captures the Russian attitude as well as any: “Well, Prince, Genoa and Lucca are now become no more than private estates of the Bonaparte Family. No, I warn you, if you do not tell me we are at war…you are no longer my friend.”2 Tolstoy emphasizes how Napoleon continued the French policy of using peace as an extension of war to aggrandize the state—now officially recognized, by the French at any rate, as an empire. Bonaparte, tossing away pretense, had made himself Napoleon I of that empire. In addition to closing all ports under French control to British commerce, and those of Spain in late 1804, Napoleon’s actions, especially his extra-judicial murder of the Duc D’Enghien after kidnapping him from a neutral area of Germany, led the great powers of Europe to form yet another coalition against him.3 The young Tsar Alexander I made common cause, as had his father, with the Austrians, and accepted British financing to rid Europe of the French menace. Britain, after two years alone against the might of France, now had great continental armies available to pull Napoleon’s Grande Armée eastward from its cantonments around Boulogne and the other channel invasion ports.4 As discussed in chapter 4, Napoleon’s decision to abandon the invasion of England in 1805 occurred for this reason as well as the undoing of his complicated plan to break the British blockade—not the Battle of Trafalgar later that October.

It is to the Grande Armée that we must now turn. Napoleon had considerably refined the French military into an unprecedented operational tool—a field army of unprecedented size organized, commanded, and trained meticulously such that it could operate along multiple lines of operation in a distributed fashion on a very broad front. In short, the maestro operational artist Napoleon fashioned a tool with which to improvise his masterpieces, the brilliant and decisive campaigns of 1805–1809. The Grande Armée was this tool. First, we must understand that Napoleon inherited—or perhaps more accurately seized—a military system already molded to a rather high degree of competence and effectiveness in the crucible of the wars of the French Revolution. He had hundreds of thousands of mature, well-equipped veterans, led by experienced and competent officers, and a state that had been dedicated for 10 straight years to sustaining, training, and employing these military forces. Napoleon institutionalized these changes to the French military machine and then added additional combat power, principally through refinements in organization, education, and motivational psychology. It is to these refinements that we now turn our attention.

As outlined in chapter 2, the Napoleonic Wars constituted a combined arms revolution in tactics and doctrine. Napoleon continued this revolution, especially at the higher operational levels. Although previous generals, including Napoleon, had employed ad hoc corps, no one had formalized and institutionalized the use of multidivision formations. As the size of Napoleonic armies increased, the need to group divisions together to enhance both their survivability and combat power became obvious. However, a new level of tactical and operational command was needed for these previously ad hoc formations. Napoleon’s genius in this regard was to simply keep doing what the French had done with the division, except at a higher echelon. As an army commander in Italy and elsewhere he had found that his operational span of control could only cover, effectively, no more than about seven or eight subunits. In order to solve this problem with field armies that now numbered a dozen or more divisions each, he needed an intermediate echelon between the division and the army. One might reasonably assume that the solution was simply to create many armies and parcel out these commands to half dozen or more commanding generals, which is what the Directory had done. However, Napoleon wanted to retain absolute unity of command over one gigantic army, into which he would put most of the Empire’s combat power for his command and use only.5 This meant he had to have an intermediate level between the division and the army to effectively control this gigantic mass. Napoleon did this by creating the Corps d’Armée or army corps as a standing military formation.

The Napoleonic Corps d’Armée varied in size, often in relation to the talents of the generals Napoleon chose to command them. His first innovation in this regard was the command element for these corps. During the period of the peace after Amiens he resurrected the French rank of marshal and awarded it to the most deserving and competent (and in some cases difficult) of his contemporary revolutionary generals. This did not mean he might not give command of a corps to a nonmarshal, but his marshals were almost always his first choice to command these units. Returning to the composition of these organizations, corps usually included anywhere from two to five divisions. They also had their own corps artillery separate from the artillery organic to the divisions, usually several batteries strong, including both howitzers and regular field guns. This allowed a corps commander to weight his defense or attack using these guns. The corps also included permanent assignment of light cavalry—initially the idea was to assign one light cavalry division to each corps, but later corps might only include one brigade. This cavalry’s role was obvious, to screen the corps as well as provide operational security for it so that it might never be taken unawares. For the composition of the Grande Armée in 1805 Napoleon created seven numbered corps (I–VII) under his personal command.6 The only other substantial field army was the old Army of Italy under his most reliable general for independent field command, Marshal Masséna, a force that included many Italian troops. For all intents and purposes, Masséna’s army was really just a much larger army corps—although he would form ad hoc corps of his own as the situation dictated.7

Napoleon’s other organizational innovations vis-à-vis the Grande Armée involved doing at the level of the army the same sort of thing he did with the corps. He created specialized operational reserves encompassing all three branches. The first reserve was an infantry heavy elite corps; his Imperial Guard, composed of his own guides from the Egyptian and later Marengo campaigns; and other Republican guard formations such as the Consular Guard. The Imperial Guard included the famous grenadiers and chasseurs in their fearsome bearskin hats as well as cavalry, initially mounted chasseurs and grenadiers a cheval. The Guard also included the renowned “beautiful daughters,” 12-pounder field guns of the Guard Artillery, as well as special guard horse artillery. It was an elite combined arms corps that eventually grew into an army within an army. Napoleon rarely used it en masse, but was prepared to do so in extreme circumstances such as at Krasnoe (Krasny) in 1812 and Waterloo in 1815. The Guard was above all both a tactical and operational reserve and would serve in this latter function as a replacement army when Napoleon lost so much of his regular army in Germany in 1813.8

The second element that Napoleon created as a standing reserve was his artillery. This mostly consisted of the Guard Artillery mentioned earlier, but he often augmented it with artillery from other sources to achieve massive firepower at a decisive point. Its operational function was to give Napoleon tactical options in choosing engagements. It should not surprise us that Napoleon used artillery in this way and that the key to his use of it was concentration and timing. His enemies often outnumbered him in terms of numbers of guns, especially after the disastrous Russian campaign, but Napoleon’s use of his artillery on a battlefield remained a wonder to all who observed it right to the end at Waterloo.9

Another operational component outside the Guard that Napoleon maintained was his Cavalry Reserve. The impetuous Joachim Murat, perhaps the most dashing (and flamboyantly dressed) cavalryman that ever lived, commanded this huge mounted force for most of its existence. By the time of the start of the 1805 campaign along the Danube, the French cavalry had become much improved. Napoleon converted the old Republican line cavalry regiments into helmeted cuirassier regiments, amalgamated together with two bear-skin-capped elite Carbinier regiments into several divisions with supporting horse artillery. He also amalgamated the dragoons and light cavalry (hussars and chasseurs) into separate dragoon and light cavalry divisions. Of particular interest in 1805 was his experiment of including with this reserve dismounted dragoons, whom officers like Generals Marie-Victor Latour-Maubourg and Louis Baraguey D’Hilliers attempted to resurrect as mounted infantry. The great problem here was that since there were so many dragoon regiments and only so many suitable mounts, a much larger and hardy horse being required to carry the considerable kit of the dragoons. As a result, almost half of these regiments served on foot as light infantry in 1805, initially to be remounted after the invasion of England. By 1806, Napoleon was finally able to mount them after capturing the excellent stocks of horses in Saxony and Prussia. By that point the dragoons had become a sort of medium-heavy cavalry, often being used in the same manner as the cuirassiers. For the 1805 campaign, this large force would number over 20,000 men and gave Napoleon many operational options, including using it independently if needed.10 Finally, Napoleon could, and did, use entire Corps d’Armée as reserves, for use as opportunity dictated, especially if they had not been decisively engaged but were near enough for an operational pursuit.

At the top of this fearsome instrument of war, Napoleon placed himself, achieving absolute unity of command in strategy, military affairs, and the formulation of what we today would call national security policy. Napoleon informed this unity with a polymath-savant’s brain—he ran this enterprise using the subtle genius of his computer-like mind and his almost inexhaustible capacity for work. His predecessors in this method of civil-military rule are few and constituted his role models—Frederick the Great; John Churchill, Duke of Marlborough; Gustavus Adolphus of Sweden; and Julius Caesar. Napoleon surrounded himself with a staff whose one purpose was the rapid transcription and delivery of his orders and collection of reports and intelligence from his subordinates and augmented with a group of highly trusted aides de camp who could and often did act on his authority at critical points on the battlefield. These men included A.J.M. René Savary, who acted during the 1805 campaign as both an aide and intelligence officer; the scrappy Jean Rapp; and the redoubtable Georges Mouton (later Count of Lobau), whom Napoleon referred to as his “lion.” It was Europe’s first modern general staff, but it would soon be eclipsed in the aftermath of Prussia’s defeat in 1806 and it absolutely depended on the genius of Napoleon to function smoothly.11

Two other innovations must be discussed. The first was Napoleon’s complete revamping and overhaul of French officer education. Much of great value in the old Royal education system had been swept away by the Revolution but Napoleon made wonderful progress in reestablishing a system of schools to train new officers as well as further educate field-grade leaders. However, all observers agree his incredible wastage of officers, especially junior ones, in his many bloody campaigns threatened to overwhelm the output of this educational system, a system that did not serve him as well as it might have had he had a period of peace to consolidate his reforms. The second innovation regarded his institutionalization, across all of society, of his system of merit in the creation of the legion of honor. Napoleon led the way, always wearing his own legion of honor ribbon prominently, as did any soldier or civil servant who was awarded one. Single-handedly he instituted a device that increased the combat performance of his troops using an institution of honor instead of relying on the older Republican call to virtue. He democratized reward, and it paid him handsomely again and again. Today’s militaries owe their own systems of awards and commendation primarily to Napoleon.12

The final innovation for discussion involved Napoleon’s revolution in military strategy, best highlighted by the campaigns of 1805 along the Danube, 1806 in Saxony and Prussia, and, to a lesser extent, in Poland in 1807. As one historian has noted, the Grande Armée gave Napoleon the power to “scramble” his way to victory because his enemies were unable to avoid being fixed and defeated by this new and powerful system of operations.13 Like Suvorov, but on a scale never practiced by the Russian, Napoleon intended the largest possible operational meeting engagement—which sometimes became an entire campaign. This was Napoleon’s idea of strategy, as conceived by both Clausewitz and Jomini, of choosing to devote the bulk of his military power to one theater of operations and then aiming relentlessly at the complete destruction of his adversaries’ military forces in one campaign season. Clausewitz labeled this form of war the higher form or what Jon Sumida has called “(Real) Absolute War.”14 Clausewitz most famously describes it as follows:

one might wonder whether there is any truth at all in our concept of the absolute character of war were it not for the fact that with our own eyes we have seen warfare achieve this state of absolute perfection. After the short prelude of the French Revolution, Bonaparte brought it swiftly and ruthlessly to that point. War, in his hands, was waged without respite until the enemy succumbed, and the counterblows were struck with almost equal energy.15

This passage comes from Clausewitz’s book on war plans (Book 8), and emphasizes his conviction that a form of absolute war could exist in reality and not just in the abstract, as evidenced by Napoleon’s campaigns. Also, the topic of war plans supports a contention throughout this book that we are talking about the operational level of war—war planning constitutes a supremely operational process, especially as discussed in most of Clausewitz’s final book, which addresses how to use military forces to accomplish objectives that have political value. However, the downside of this form of war was that it left all the most important decision-making to Napoleon. Unlike the British maritime command system that relied on collective and decentralized execution across vast distances, Napoleon concentrated all the operational decision-making for the main theater inside his own mind. As the scale of conflict grew and the talent pool of French generals able to operate independently of Napoleon declined, this unity would turn into a deadly trap—but for the first years it yielded a harvest of unprecedented success. Napoleon longed for the telegraph, and in fact created a good semaphore telegraph that gave him key advantages in 1805 as he launched his campaign. Nonetheless, his ability to communicate and direct actions in the expanding dimensions of the operational level of war—an expansion for which he to a great degree was responsible—constituted one of his Achilles’ heels.16

ULM-AUSTERLITZ: THE TRIUMPH OF THE SEAMLESS CAMPAIGN

Recall that the Soviet operational artists desired a campaign of seamless, sequential blows. Whether from a standing start or after a period of defensive activity, they preached the merits of an approach that might avoid the “culminating point of victory” that had seemed to bedevil all sides in World War I.17 Operational art also involves distributed and deep operations on a broad front, reflecting not so much mechanical stops and starts, but rather fluid dynamics, the motions and eddies of fluids interacting. Napoleon’s first advantage in 1805 was his enemies’ phenomenal failure to concentrate their forces against him in the decisive theater. The Third Coalition included the Kingdoms of Sweden and Naples and accordingly the allies decided to leverage their advantage in manpower in much the same way they had in 1799, by trying to accomplish all their political objectives with associated military efforts in all the various theaters of war. After August 1805, when the Coalition took its final form, it had at its disposal over 500,000 Austrian, Russian, British, Neapolitan, and Swedish troops with the very real likelihood that a neutral Prussia might join the coalition under the right circumstances.18

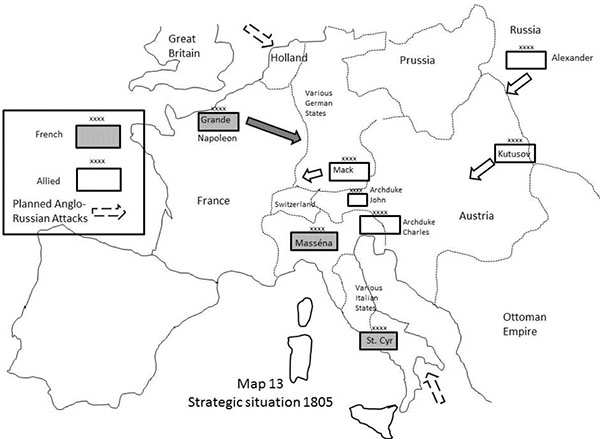

Map 13 Strategic situation 1805

The Third Coalition’s plan aimed at nothing less than the restoration of French borders to those of 1791. It intended to do this by applying all its military means to each territorial reacquisition required by this end-state. Accordingly, the Coalition’s leaders dispersed their efforts on a very broad scale in order to accomplish “liberations” of Holland, Hanover, Switzerland, Italy, South Germany, and Belgium. The key was the Russian mobilization and the hope that Prussia would at least allow a Russian army (under Baron Levin Bennigsen) to pass through its territory to threaten the middle Rhine. An Anglo-Swedish-Austrian army, again passing through Prussia, was to reconquer French-occupied Hanover and from there proceed to Holland. Two other Russian armies were also on the march to join the Austrians in southern Germany—the first under Prince Mikhail Kutusov and a second army some distance behind accompanied in person by Tsar Alexander. With little concern about the distance the Russians had to march; the allies approved the Austrian plan of an immediate offensive by an Austrian army under Archduke Ferdinand and General Karl Mack into Bavaria and south Germany. Additionally, since Napoleon had twice made major efforts in Italy, Archduke Charles assumed command of the largest Austrian army in North Italy. A British, Austrian, and Neapolitan army moving up from the south supported Charles’s operations and could cooperate in the expulsion of the French from the entirety of Italy. Another Russian force would operate along the Adriatic coast in support of the Austrians. Finally, a smaller Austrian army under Archduke John defended the Tyrol and threatened Switzerland. It was an ambitious program that looked much like the Second Coalition’s approach in 1799 (see map 13). 19

Napoleon made mincemeat of these plans by his blitzkrieg-like descent on the overextended Austrian army of Archduke Ferdinand after it had invaded France’s ally Bavaria. Ferdinand and his chief of staff Feldmarshalleutnant Karl Mack halted in an exposed position in Swabia west of Munich, awaiting the reaction of the French, as well as the arrival of the Russians, rather than continuing the offensive. Also, they operated in the belief that theirs was not the major theater and that Archduke Charles, with the bulk of the Austrian army, would absorb Napoleon’s main blows in Italy just as it had in 1796 and 1800. The French would be pinned down in a bloody slugfest as the Anglo-Russian-Neapolitan Army came up from the south to threaten their flank.20

Napoleon, however, needed a decision quickly—before Prussia removed itself from its metaphorical fence perch. This meant he must strike down the Danube at the sources of Austrian power, destroying large portions of the Austrian army and whatever Russian forces that might be in the vicinity. The Austrians’ ill-advised offensive into Bavaria played right into Napoleon’s hands, as he would be succoring an ally who had been violated by Austria, adding its not inconsequential military (25,000 troops) to his own on good terms. This approach also secured Napoleon’s lines of communications down the Danube through southern Germany and back to France through friendly country.21

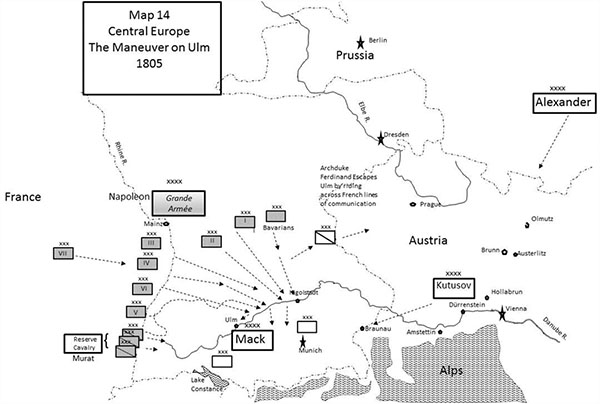

Napoleon’s use of his many army corps and cavalry reserve to this end are justly famous. Murat was sent with the cavalry reserve to form an operational screen for Napoleon’s broad advance along a front of several hundred kilometers from the northwest across the middle of Rhine. Murat’s force not only covered this advance, but it also distracted the Austrians’ attention toward the Black Forest and Baden instead of upon the storm moving rapidly across their right flank. (see map 14) Mack and Ferdinand believed the deception and remained fixated on the threat to their west, which they thought was advancing through the narrow passes in the Black Forest. Once convinced his operational deception had succeeded, Murat doubled back and used the mobility of his cavalry to appear on Mack’s rear and flank. Murat also took over the containment of the Austrian forces along the north bank of the Danube. This operation remains a text book example of operational deception and economy of force. Meanwhile, French troops marched rapidly to the Danube and began crossing on September 25.22

From Albeck outside Ulm all the way to Ingolstadt on the Danube almost 100 miles away, French corps developed, fixed, or scattered Austrian detachments and concentrations, arriving deep in the Austrians’ rear at Munich by October 6. Meanwhile, the Russians under Prince Kutuzov, one of Suvorov’s ambitious protégés, plodded slowly up the Danube, unaware that the Austrian army at Ulm was at risk. By the time Ferdinand and Mack realized the danger, it was too late. Attempts to break out to the north failed—although they considerably disrupted French logistics. One French division fought off an entire Austrian corps on October 11 at Albeck (just north of Ulm), but was rescued by the arrival of its parent corps (Marshal Michel Ney’s VI) the next day. Ferdinand and about 6,000 Austrian cavalry broke out of the trap, abandoning the hapless chief of staff, “the unhappy Mack” and half of his army inside Ulm. By bluff and demonstrations of force Napoleon hustled Mack into surrendering over 27,000 Austrian troops at Ulm on October 21, ironically the same day Nelson destroyed the Franco-Spanish fleet at Trafalgar. In the aftermath of the capitulation at Ulm, another 25,000 Austrians fell into French hands, essentially eliminating an Austrian field army by the use of maneuver and effective, if unintended, engagements. Napoleon had issued his troops two pairs of boots, and it was probably around this time that they discarded the first pair, if not soon afterward. They famously joked that their emperor won his battles with their feet!23

Ulm emphasized all the major elements of Napoleon’s operational art. His goal of finding and fixing his opponent was achieved when he managed to place the Grand Armée east of Ulm across Ferdinand’s line of retreat. Further, he had concentrated the bulk of his army on the very spot that the Austrians and Russians needed to concentrate their own forces. Although Napoleon was not quite sure of the location of the main Austrian army, he did know that he had placed himself on interior lines to prevent its concentration. As a result, his subordinates defeated Austrian attempts, both to concentrate and to escape, in detail. In the process he bagged the bulk of the Austrian artillery and infantry. Mack neither had the imagination nor the fortitude to break out once he realized his predicament—although Ferdinand did manage to get away with about half of the cavalry he had broken out with.

At the same time Ulm was surrendering, the situation was becoming more complicated. Masséna performed his role of fixing Archduke Charles’s larger army by attacking at Caldiero on October 29 and being repulsed. Charles deemed himself unable to send reinforcements through the Tyrol to help Mack. The entire Bavarian Army was incorporated into the Grand Armée and put to use immediately in the corps of Marshals Bernadotte (I) and Ney (VI). Meanwhile, the VII Corps of Marshal Pierre Augereau arrived from its station in Brittany and fulfilled the function of a second operational echelon, scooping up wayward Austrian detachments as it moved east to support Napoleon. On the negative side, the Prussians were beginning to mobilize after French violation of their principality of Anhalt (by Bernadotte) and it was clear to the Austrians and Russians that they must avoid further battle. The first part of the campaign was over, but not the war. If Prussia came into the conflict, Napoleon’s strategy of concentrating the bulk of his combat power into one theater might backfire on him, despite the auspicious beginning. Also, he had to worry about Archdukes Charles and John combining and abandoning the defense of the southern Hapsburg realms and advancing on his flank (and later his rear).24

Map 14 Central Europe The Maneuver on Ulm 1805

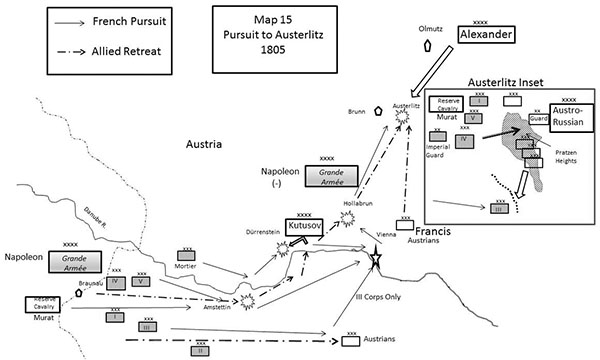

Napoleon now tried to reap further rewards from his success at Ulm by destroying the exposed Russian army under Kutusov, which had advanced as far as Braunau on the Danube (see map 14). Kutusov fell back as soon as he learned of Ulm. Clausewitz has pointed out that the fruits of victory are often squandered when generals fail to follow up victory by a vigorous pursuit. Napoleon can hardly be criticized in late October 1805 on this account; his forces were scattered and in a state of disorganization with many dangers still to face, yet he pressed on with the easternmost corps, hoping for the best. Kutusov frustrated this purpose by deftly playing a game of hide-and-seek along the Danube, which forced Napoleon to advance down both sides of the river. The French army started to dwindle in size as it bled off troops and combat power to secure its lines of communication and as new missions were given to others to account for the Austrian forces in the Tyrol. After a sharp engagement at Amstettin with the advanced guard under Murat, Kutusov put the river between himself and the French (see map 15).25

In response, Napoleon created an ad hoc corps under General Edouard Mortier from several divisions belonging to other corps for operations along the north bank of the Danube. This corps became isolated north of the Danube and offered Kutusov the chance to destroy it at Dürrenstein on November 11. A tenacious defense and the operational durability of a French division under General Gazan served to keep the Russians at bay until the division of General Dupont came up, causing the Russians to break off the action. On the south side of the Danube, Davout’s III Corps was able to scoop up the bulk of Merveldt’s Corps on November 8. However, the damage was done and Kutusov retreated rapidly toward a second Russian army of 40,000 men, led by General Buxhowden and the Tsar, then located in Moravia.26

Napoleon now improvised a new plan of operations to trap Kutusov before he could join up with Buxhowden. He ordered Bernadotte’s relatively fresh corps north of the Danube while informing Murat that if he could capture one of the bridges over the river in Vienna, he was to push north with his cavalry and Marshal Jean Lannes’s V Corps to take Kutusov in the flank or rear as he was pursued by Bernadotte and Mortier. The first part of this plan went awry when Bernadotte expended more than two days to cross the river and begin his pursuit. As it turned out, Murat and Lannes captured the bridge in Vienna with no losses but in pushing north against Kutusov they ran into his strong rearguard at Hollabrunn under the redoubtable General Peter Bagration on November 15. Here Kutusov tricked Murat into agreeing to an armistice, allowing the bulk of his army to escape and join forces with the Tsar on the road to Olmutz. Napoleon was furious when he found out about the armistice and ordered Murat to attack immediately. Bagration conducted his usual ferocious rearguard action but lost 2,000 men before slipping away. By November 23, Napoleon and the lead elements of the Grande Armée were in Brünn.

It is worth reviewing just where the various components of the Grande Armée were at this time. A glance at the map reveals that Napoleon’s forces were spread across most of central Europe, from Bavaria to the Dalmatian city of Ragusa (modern-day Dubrovnik) and from Tuscany to Brünn. By the end of the month, the emperor was near the little village of Austerlitz in Moravia, with the corps of Soult (IV) and Lannes, Murat and the bulk of the cavalry, the grenadier division of General Oudinot, and his Imperial Guard. Both the corps of Davout and Bernadotte were over a day’s march away. Napoleon now made one of the most effective, and short, retreats in his long career. He had occupied Austerlitz and the high ground just west of it, the Pratzen Heights. When the now unified and reinforced Austro-Russian army of 90,000 men advanced from Olmutz, Napoleon deftly pulled back from Austerlitz and abandoned the high ground on November 30, retreating just beyond the low hills to the west, which hid his forces. His new line was positioned on reverse slopes, somewhat in the manner that Wellington would employ in Spain, anchored by the Santon Hill in the north and various strong points in the south around the castle of Sokolonitz and the village of Telnitz. These last two locations were lightly held by detached elements from Soult’s corps. The remainder of the army was hidden from view by the aforementioned low hills. His pickets and cavalry aggressively denied the Allies the ability to determine just where his forces were (see map 15 inset).27

Map 15 Pursuit to Austerlitz 1805

The Allied army, learning of Napoleon’s withdrawal, occupied the high ground on December 1 in the confidence that Napoleon was preparing to withdraw rapidly toward Vienna. Napoleon’s retrograde maneuver also convinced the Tsar and the coterie of young and impetuous officers surrounding him that Napoleon was fearful of an attack—so they should attack, immediately. Kutusov, nominally in overall command, was against any sort of offensive and favored letting Napoleon withdraw unmolested for the time being. The Austrian staff officer Weyrother presented the Tsar a plan, without Kutuzov’s endorsement, in which the bulk of the Allied army, over 50,000 men, would debauch upon Napoleon’s apparently overextended and weak right flank, and cut him off from a retreat upon Vienna and reinforcements. One can hardly imagine Weyrother doing something like this when he had served under Suvorov—but Kutusov and Weyrother had no such relationship. Further, the Allies would then pursue whatever remained of the Grande Armée into Bohemia where presumably the Prussians would finally make their appearance as a full-fledged member of the coalition. Here Napoleon could be finished off once and for all.28

Napoleon intended this response. He knew he was too weak to attack the Allied Army and his parleys prior to the battle with the representatives of the Tsar and Austrian Emperor convinced them in turn that he was in a vulnerable predicament. However, by December 1, Bernadotte’s corps had arrived and was in position on Napoleon’s left flank to further deceive the Allies about the weakness of Napoleon’s right. He was banking that Davout, marching hard from the vicinity of Vienna, would arrive en echelon during the battle to meet and fix the Allies’ main attack on the presumably vulnerable right flank. This was a supremely operational calculation, based on Davout’s demonstrated competence and Napoleon’s judgment about how the Allied attack would develop in the short winter day of early December. Napoleon was convinced that the Allies would denude the strongest point in their line, the Pratzen Heights, leaving themselves open to a devastating counterattack. Also, like Nelson at Trafalgar, Napoleon ensured all his marshals and many of his soldiers knew the outlines of his plan and intentions for them. He visited campfire after campfire on the cold winter night of December 1–2 after a meal with his marshals and staff to encourage and explain things to his grognards (“grumblers”).29

The resulting Battle of Austerlitz on December 2 is justly famous as Napoleon’s tactical masterpiece. However, Napoleon’s operational combinations prior to the battle, much as Nelson’s prior to Trafalgar, did as much to determine the outcome as the actual fighting. His only major decision during the battle involved assessing the moment when the Allied forces attacking his weak right flank had become sufficiently vulnerable for him to launch the larger part of Soult’s Corps to retake the Pratzen Heights and hit the Allied columns in the flank and rear. He did this after the bulk of the huge Allied column had proceeded south. Nonetheless, hard fighting took place across the front but with a French corps now on the high ground separating the two unequal wings of the Allied Army. Napoleon had placed himself again in the key central position. The Allies fought furiously, but the disruption and shock of this action unhinged their leadership and dispirited the troops. The Russian troops broke after their final counterattacks uphill against the French failed, mostly due to the deft use of artillery by the emperor’s gunners. As they fled across the thinly frozen lakes and ponds of south of the Pratzen, the French artillery broke the ice and caused further casualties from drowning and exposure in the frigid waters. By the end of the day the French had killed or wounded over 14,000 enemy troops and captured another 11,000.30

The catastrophe of Austerlitz proved too much for the Austrian emperor Francis, who agreed to an armistice subsequent to further negotiations for a permanent, but disadvantageous peace. The Russian tsar, humiliated that his first battle had been a resounding defeat, in no small part because of his poor judgment, retreated toward Russian Poland with a much reduced Russian army (mostly composed of the seemingly indestructible Bagration’s corps). The Prussians, who had mobilized their army and were on the point of attacking Napoleon’s strategic flank and rear, hastily demobilized and sent out messages of peace and conciliation to Napoleon. The Swedes and British in Pomerania had no way to attack the French Empire, at least by land, and shelved their plans for an invasion of Hanover and Holland. Although the aftermath of Austerlitz marked the end of the Third Coalition, the Russians, British, and Swedes were still technically at war with Napoleon. Still, it seemed for a time that Europe might at last enjoy a period of peace. As for Naples, it was overrun in early 1806 and the Napoleonic Kingdom of Naples established with Napoleon’s oldest brother Joseph as King.31

THE JENA CAMPAIGN—NAPOLEONIC OPERATIONAL ART À OUTRANCE32

The anti-French government of William Pitt the Younger, its architect mortally ill, was replaced by the more conciliatory government of Charles James Fox. However, peace feelers between the British and French ended up contributing to another general conflagration and central Europe was given no respite from war. Trafalgar had changed the strategic calculus and Napoleon knew it. He could not reasonably entertain the notion that he might ever be able to invade Great Britain and he only had two real options to bring about peace. One was the stick he had been using all along, to close more of Europe’s ports, such as those of Austria, now an unwilling French ally, to British shipping. The other was a carrot—he needed to offer something tangible to the British for a favorable peace. Napoleon thought the electorate of Hanover, German origin of the reigning British royal family, might do the trick. However, the emperor had already promised Hanover to Prussia as the reward, or rather bribe, for staying out of the Third Coalition. When Prussia’s leaders learned of Napoleon’s duplicity, the war faction led by the Prussian King’s beautiful and Franco-phobic queen Louise clamored for war with France. By August 1806, Prussia had secretly decided for war and entered Saxony that September. In a show of mindless bravado, officers of the elite Guard du Corps regiment sharpened their swords on the steps of the French embassy. On October 7, Prussia delivered an ultimatum to France that was tantamount to a declaration of war, but instead of waiting for her new Russian allies to unite with them, the heirs of the army of Frederick the Great marched off in great pomp and arrogance to humble the hubris of France.33

The Prussian army of 1806 has often been criticized for being an outdated military institution, living on the glories and traditions of “Old Fritz,” impervious to reform, and completely unready for a war in the new modern style.34 This was not entirely true, although it certainly proved no match for Napoleon. Ever since Prussia’s withdrawal from the First Coalition in 1795, significant members of Prussia’s officer corps made study and knowledge of the new French operational methods of war their focus. Unfortunately, these elements, which we shall label the reform faction, resided inside a relatively new institution, the Quartermaster General Staff (QMGS, founded originally by Frederick the Great). This unique group of officers was analogous to the French staff officer corps of the prerevolutionary era from which officers like Berthier sprang. The staff was composed of three sections and also involved an element for officer education. After the catastrophe of 1806 and 1807, this group controlled the Prussian military and created an entirely new operational framework to oppose Napoleon and the French—the Prussian Great General Staff.

To fully understand the origins and purpose of the QMGS and new Kriegsakademie (War College), one must go back to Prussia’s enlightened policy of acquiring talented non-Prussian officers to serve in it ranks. The Prussian military institution had always had a very close relationship with the Dukes of Brunswick, sovereign German princes in their own right. Prussia often used them as independent commanders, giving them field marshal rank. Charles William Ferdinand, Duke of Brunswick (defeated by Kellermann at Valmy), came from the old school of generalship but was an astute judge of men. It was on his recommendation that the founder of the new Kriegsakademie and head of the third section of the QMGS, a Hanoverian officer named Gerhard Scharnhorst, came into the Prussian army.35

Scharnhorst came from a humble background; his father was a soldier but not an officer, but did well enough to earn a place for his son in the Hanoverian cadet school. While serving as chief of staff for the Hanoverian army, Scharnhorst’s combat record and writing brought him to the attention of the Duke of Brunswick. Brunswick recommended him to the King of Prussia and Scharnhorst transferred into the Prussian service as a major, and shortly after, the King promoted him to lieutenant colonel.36 He served simultaneously in two jobs. His first and more influential position was as the director of the revamped Kriegsakademie that trained infantry and cavalry officers. Here Scharnhorst met the young Clausewitz and formed a close professional friendship that lasted until the former’s death in 1813. Additionally, Scharnhorst was appointed to the QMGS that was reorganized by Colonel von Massenbach in 1803 into three logistics planning sections. Scharnhorst headed up the section assigned to contingency planning for operations in the west against the French. According to Clausewitz, Scharnhorst was “one of those rare individuals in whom theoretical knowledge and scholarly ambition are combined.” Scharnhorst used these skills to educate his students and his planning section on what he correctly viewed as the profound changes in war wrought by the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars. However, the old guard in the Prussian army remained aloof from new ideas and resistant to the idea of military reform.37

Scharnhorst and his confederates, men such as Clausewitz, Gebhard von Blücher, Baron Carl von Müffling, and to a lesser degree Brunswick, attempted to reorganize the Prussian Army on the eve of war with France. They were opposed by the bulk of the officer corps, which included over 142 generals, half of whom were 60 years or older, including four older than 80 years. The Prussian army, like the Royal French army, was mostly officered by aristocrats who had inherited and had not earned their commissions. Despite some improvements in skirmishing procedures, the Army retained the linear tactics of Frederick the Great. The Prussians did try to organize combined arms divisions at the eleventh hour in 1806 after the field army marched toward the seat of war in Saxony, but this perhaps hurt more than it helped. There was plentiful artillery, however, it was scattered about with no concept of how to use it as mobile fire power to weight a battle. The cavalry was superbly mounted, but had little experience in combined arms warfare and was not organized to screen and provide reconnaissance for the army. The cavalry’s self-image was that of the most important arm, deciding the battle much as Baron von Seydlitz had at the Battle of Rossbach (1757) by charging “hell for leather” at its enemies. Finally, there was no standardization of organization above the division level, no army corps counterpart to the French. The army was visually impressive, but it was an antique, with every bit as much baggage as a standard 18th-Century army but without Frederick’s genius to move and maneuver such a cumbersome machine, either operationally or tactically. Clausewitz remarked of it, “behind the fine façade all was mildewed.”38

The greatest mistake that the Prussians made, after declaring war in the first place, occurred at the strategic level. Ignoring the cautious advice of Scharnhorst to wait for the Russians, Brunswick and Prince Friederich Hohenlöhe, who commanded the next largest army, spent precious days arguing over which axis to advance from Saxony while Napoleon rapidly concentrated his forces as he had done in 1805 for the main effort in the decisive theater. The Prussians launched an offensive toward the eastern side of the Rhine before they had completely mobilized or given the Russians time to join them. They and their unwilling Saxon ally simply grouped themselves into three armies of varying size: the largest numbered about 70,000 troops and commanded by Brunswick who also served as overall commander in chief, Hohenlöhe’s army (50,000), and General Philip von Ruchel’s small army (15,000). They advanced with fewer than 150,000 troops as opposed to Napoleon’s battle-tested, rested, and victorious Grand Armée of over 180,000. There were additional fortress garrisons and detachments that the Prussians had elsewhere, but in moving out to meet Napoleon they did not bring all their available combat power with them, leaving a “strategic” reserve of 13,000 out of supporting distance to their rear.39 Writing not long after participating actively in this campaign, Clausewitz claimed desertion and straggling lowered the effective Prussian-Saxon field force to approximately 130,000 effectives.40

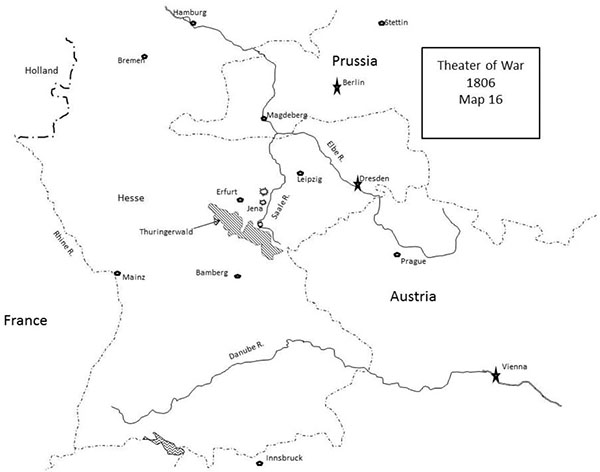

Map 16 Theater of War 1806

For once, Napoleon’s strategic intelligence agents failed him and only after the Prussians had entered Saxony did he realize that war was imminent. His hopes for peace treaties with Russia and Great Britain proved vain and he concentrated the bulk of his combat power against the Prussians. The Grande Armée was scattered from the Inn River to its northernmost cantonments in Hesse along the lower Rhine (see map 16). By September 18, Napoleon had made up his mind and a flurry of activity ensued at his headquarters. He issued an amazing 120 separate orders whose intent was to concentrate the bulk of the Grande Armée near Bamberg just west of the dense Thuringerwald Mountains through which he intended to advance into Saxony. The Imperial Guard infantry in Paris were loaded into wagons and moved rapidly along good roads to Mainz on the Rhine where they disembarked and continued on foot to the east. Napoleon and his staff followed a week later. By the first week of October, the bulk of his forces were concentrated between Bamberg and Wurzburg, before Prussia’s ultimatum arrived on October 7.41 Earlier, Napoleon had also issued orders tantamount to the mobilization of a second strategic echelon (using the Soviet terminology) by calling up 50,000 conscripts of the class of 1806 as well as activating another 30,000 French reservists (troops who had been discharged after earlier campaigns but were still on the rolls of the French army). In this way he mobilized the necessary reserves to either reinforce his army for a longer effort to the east against the Russians or take defensive measures. He also learned the Russians were joining Prussia, Sweden, and Britain in a Fourth Coalition.42

Napoleon decided to advance through the three narrow passes of the Thuringerwald, thus screening his army. He sent his infantry forward first in order to get the maximum amount of combat power through the dense hills. He counted on the Prussians not reacting swiftly enough to defeat the heads of his columns as they emerged from the passes as well as on the audacity and speed of his own advance. His campaign design is best gained from a complete reading of his famous operations order sent to Marshal Soult after Napoleon arrived at Wurzburg:

I propose to debouch into Saxony with my whole army in three columns. You are at the head of the right-hand column with Marshal Ney’s Corps half a day’s march behind you and 10,000 Bavarians a day’s march behind him, making altogether more than 50,000 men. Marshal Bernadotte leads the center, followed by Marshal Davout’s Corps, the greater part of the reserve Cavalry, and the Guard, making more than 70,000 men. He will march by way of Kronach, Lebenstein and Schleiz. The V Corps [Lannes] is at the head of the way to Coburg, Grafenthal and Saalfeld, and musters over 40,000 men.

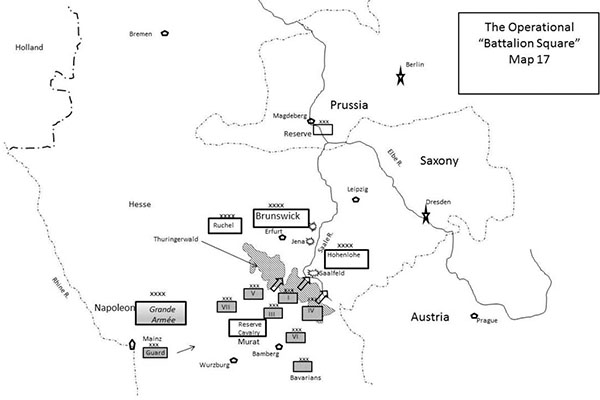

With this immense superiority of force united in so small a place you will realize that I am determined to leave nothing to chance, and can attack the foe wherever he chooses to stand with nearly double his strength…. If the enemy opposes you with a force not exceeding 30,000 men, you should concert with Marshal Ney and attack him…. From news that has come in today [October 5] it appears that if the foe makes any move it will be towards my left; the bulk of his forces seem to be near Erfurt…. I cannot press you too earnestly to write to me frequently and keep me fully informed of all you learn from the direction of Dresden. You may well think that it will be a fine thing to move around this area in a “battalion square” of 200,000 men. Still, this will require a little [operational] art and certain events.43

Not mentioned in this order was Augereau’s VII Corps, which followed in the wake of Lannes (see map 17). Napoleon had organized his army into a giant square composed of roughly six army corps. His method here differs somewhat from that employed at Ulm in that this operational scheme gave him the maximum amount of flexibility to initiate one of his operational meeting engagements. Whichever front met the enemy would fix it and then engage it decisively in concert with the second line of operational reserves. At first there would be one axis determined absolutely by the passes through the mountains, but once into the more open country beyond in the Saale River valley, Napoleon would in fact turn the entire axis from the northeast to a more northerly direction toward Erfurt. In addition to the second line of operational reserves, in some cases he even had a third line, such as the large Bavarian division under Napoleon’s brother Prince Jerome.

Map 17 The Operational “Battalion Square“

The Prussians and their archaic style of command played right into Napoleon’s operational scheme. A reconnaissance by Scharnhorst’s protégé Captain Müffling revealed that Napoleon had already left Bamberg with a very large force marching for Saxony. Previously, Brunswick and Hohenlöhe had argued about what to do, whether to threaten Napoleon’s rear and flank by advancing further north or push on and meet him east of the Saale River. Brunswick dithered and cancelled his moves from Erfurt toward Wurzburg. Hohenlöhe interpreted this to mean that this allowed him to execute his alternate plan of moving on Bamberg along the eastern side of the Saale. Hohenlöhe pushed out his strong advanced guard division under the King’s cousin, the firebrand Prince Louis Ferdinand of Prussia, to Saalfeld and another division that included 3,000 sullen Saxons under General B. F. Tauentzien to Schleiz.44

Referring to Napoleon’s order to Soult, these rash moves placed Hohenlöhe’s forces right in the path of Lannes’s left-side column and Bernadotte’s strong central column, both now already through the Thuringerwald (Thuringian Forest). Disaster struck quickly. Bernadotte pushed Tauentzien out of Schleiz on October 9. Although casualties were low, Tauentzien’s division was thoroughly disrupted and was lucky not to lose its Saxon troops completely to capture or defection. Hohenlöhe pulled them back to reorganize them. Louis’s division was then mauled by Lannes’s infantry and cavalry on October 10 at Saalfeld and the prince was killed in personal combat by a French hussar. Here Prussian losses were significant, totaling 2,700 as opposed to less than 200 for the French. These initial defeats unhinged Hohenlöhe and, especially, Brunswick, who now ordered his armies to concentrate northwest of the Saale River around Weimar. Napoleon interpreted Brunswick’s moves to indicate he was pulling back east of the river to protect Leipzig, the capital of Saxony. In doing so, Napoleon “lost” the Prussian army, as he had the Austrians at Ulm. Napoleon’s giant operational square, which had been pivoting to the north, now turned clockwise to the northeast.45

As the Prussians withdrew, French cavalry further discomfited Hohenlöhe’s Saxon troops. Intelligence arrived at Prussian headquarters that Napoleon already had French troops (in fact Davout’s entire corps) as far north as Naumburg, which threatened the Prussian line of retreat. The fog of war had set in deeply for both sides, but Napoleon had the better tool to hand to deal with uncertainty. On October 13, Lannes, now presumably in the second operational echelon, discovered Hohenlöhe’s entire army of about 40,000 men on the flank of the Grande Armée at Jena. Using dragoons as infantry, Lannes seized the key terrain of the Landgrafenberg Heights near Jena in the immediate vicinity of Hohenlöhe (perhaps not realizing how strong he was). He then notified Napoleon of his situation, an example of the success of Napoleon’s style of mission command, best illustrated in this campaign, with trusted subordinates like Lannes and Davout. Napoleon’s plan at this point now changed as he realized the enemy was not withdrawing to cover Leipzig but seemed to be across the Saale at Erfurt. As information came in, he conceived a plan to advance again at 90 degrees to his previous axis (toward Leipzig) and on Erfurt where he now believed the main enemy army to be, anticipating a large battle on October 16.46

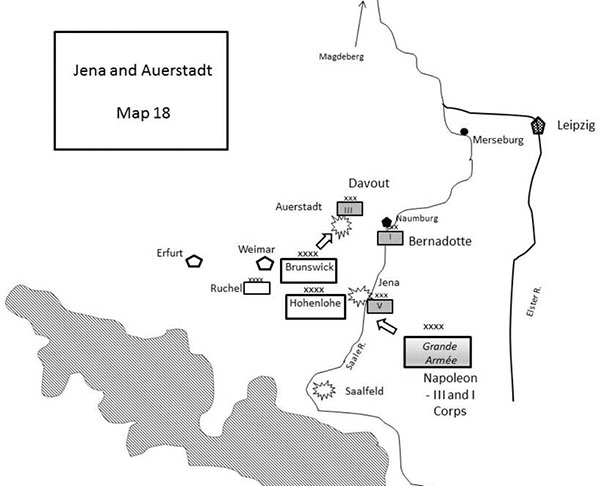

Lannes’s updated information about the actual size of the Prussian army at Jena (he estimated 30,000) set the stage for the next day’s cataclysmic events. Napoleon, believing that the Prussian main army was at Jena, issued a stream of orders to bring the main force to bear there, increasing from 22,000 to over 130,000 troops at Jena as the day wore on. It was Suvorov’s echeloned arrival on steroids! Napoleon still did not understand Prussian intentions. Once they learned that elements of the French army were as far north as Naumberg, a Prussian council of war decided to retreat to Magdeburg down the western side of the Saale through Merseburg. Hohenlöhe would cover this withdrawal with his army of approximately 38,000 at Jena and could call on Ruchel’s small army, moving across his rear in the wake of the main army, if he needed support. Brunswick, meanwhile, would take the main army just west of Naumberg through Auerstadt on the way to Freiburg and Merseburg. Thus, as October 14 dawned, Napoleon was moving upon Hohenlöhe’s sizable rearguard with the bulk of the Grande Armée.47

Even though he misunderstood the enemy’s intentions, Napoleon’s forces were well positioned to deal with the planned Prussian movements. Murat and Bernadotte had been given orders to concentrate at Dornburg, midway between Auerstadt and Jena, and could support Napoleon or Davout as events dictated. Davout was to advance south toward Auerstadt and take the Prussians in the flank or rear and to bring Bernadotte under his orders if combat ensued. Bernadotte had the same orders but interpreted them to mean that he need not support Davout, while Murat pressed south to join the Emperor at Jena. In this manner, Davout and his single corps of 26,000 troops marched directly into the path of the retreating Prussian army under Brunswick of almost 64,000 troops48 (see map 18).

October 14 became the blackest day in the Prussian army’s history. Napoleon arrived at Jena to find that Marshal Ney had launched the offensive there prematurely, and had been repulsed handily. Nonetheless, as his operational reserves arrived, the emperor fed them into the battle and before long the Grande Armée had shattered Hohenlöhe’s army. Ruchel moved up too late in support and was in turn mauled by the victorious French who used massed artillery consisting of four batteries of guns to unnerve his infantry and then scatter them. Napoleon believed that he had shattered the main Prussian army only to receive a dispatch late that night from Davout, over 20 miles away at Auerstadt, informing him that his lone corps had successfully repelled the main Prussian army under Brunswick. Brunswick had been mortally wounded, leaving the Prussian army leaderless at its most critical moment. Davout’s III Corps had then resumed its advance and the entire Prussian army literally disintegrated on the field of battle. Bernadotte had never supported him, despite Davout’s urgent need and the furious sound of cannon just to his north. In contrast, Soult marched to the sound of the guns, despite not receiving any definitive orders from Napoleon, getting his lead division into the fight at a critical moment on the enemy’s right flank at Jena. Davout’s excellent generalship aside, his corps’s performance at Auerstadt stands as a testament to the durability of Napoleon’s Corps d’Armée. French losses for both battles totaled 12,000 (mostly in Davout’s and Ney’s corps) while Prussian losses exceeded 39,000 killed, wounded, and captured, with numerous units fleeing as disorganized refugees and the army’s line of retreat cut.49

Map 18 Jena and Auerstadt

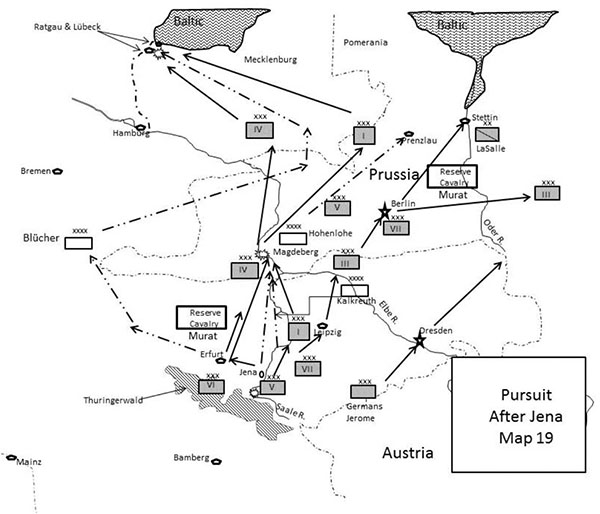

The campaign was not over. Clausewitz used Jean-Auerstadt as the supreme example of how a pursuit after a hard-won victory (or two in this case) increases exponentially the scale of an enemy’s defeat if conducted with the proper energy and boldness.50 Before light on October 15, Napoleon began to issue orders for an operational pursuit. Napoleon had his reserve cavalry corps, Bernadotte’s I Corps (due to that marshal’s indolence), and most of Soult’s Corps relatively fresh and in hand. They ended up serving as essentially a second operational echelon, poised to gather up the fruits of victory operating as what the Soviets called the deep exploitation force. Napoleon unleashed these against the fleeing and disorganized Prussians, giving them no chance to reform and establish a defense before Berlin. He planned to send Murat, Ney, and Soult toward Erfurt and then turn them north toward the Elbe to apply pressure on the mass of refugees that the Prussian army had become. On this force’s right was the intended maneuver force of decision, four corps led by Bernadotte’s fresh troops, which Napoleon intended to reach the Elbe before the Prussians. The postbattle pursuit by Murat, using mostly the combined corps’ cavalry at Jena, yielded its first substantial success that day when the column of the Duke of Saxe-Weimar (another “detached” Prussian contingent) was bluffed out of the fortress of Erfurt and Murat gathered up some 9,000 additional prisoners from units fleeing along that axis by the end of October 16.51

On the Prussian side the goal was to reach Magdeburg and establish a defense along the Elbe before the French arrived. Three corps had formed up after October 14 from the residue of the Prussian army, the remainder of the troops from Jena under Hohenlöhe, those fleeing Auerstadt under General von Kalckreuth (20,000), and finally a third group under General Blücher, which was supposed to be serving as a rearguard for the other two. After the capture of Erfurt, Blücher joined up with Saxe-Weimar’s remnants, made the wounded General von Scharnhorst his chief of staff, and retreated on a divergent axis to west of the others as advised by Scharnhorst.52

Bernadotte, stung by the criticism of the army and Napoleon for his conduct at Auerstadt, proceeded savagely with his portion of the pursuit. The Prussian strategic reserve under the Duke of Württemberg, numbering 13,000 fresh troops, had remained at Halle awaiting further orders. Bernadotte’s corps arrived and defeated them on October 17, inflicting another 5,000 casualties against a cost of 800 men. On the other axis of the pursuit, Soult had overtaken Ney and was hot on the heels of the combined forces of Kalckreuth and Hohenlöhe. By October 20, the various French corps were either at or approaching the Elbe River. The Prussians abandoned Magdeburg and their original line of retreat toward East Prussia, reinforcements, and the Russians. Instead they veered west of Berlin, which they effectively abandoned. They were hoping the French would slow down and besiege Magdeburg, but Napoleon kept the press on, bypassing that city with Soult and Bernadotte. All the while his forces gathered up prisoners and stragglers at every turn. Ney, coming up in the second echelon, was left behind to surround and besiege Magdeburg. Blücher briefly rejoined Hohenlöhe on October 24 and assumed the role of the rearguard. The next day, Davout’s corps marched into Berlin unopposed.53

Map 19 Pursuit After Jena

Blücher and Scharnhorst turned west and away from Hohenlöhe racing toward Lübeck, perhaps hoping to be evacuated by the British navy. Instead, they met a Swedish division that had recently disembarked. Bernadotte, still marching hard, penned up Scharnhorst in Lübeck and Blücher in Ratgau (see map 19). Under assault by the corps of Bernadotte and Soult, they surrendered with over 20,000 troops on November 4–5. Bernadotte also scooped up the Swedes, effectively removing an entire army from the operational board. He treated the Swedes so cordially that they returned to Sweden full of praise for the gracious French marshal—later these fond memories caused the Swedes to invite Bernadotte to come rule Sweden as crown prince when their chronically deranged king was removed from the throne. In 1813, he “went native,” abandoned Napoleon and joined the Sixth Coalition on its march to ultimate victory. Bernadotte had taken lemons and indeed made lemonade. His dynasty still rules as constitutional monarchs in Europe today.54

As Bernadotte was scooping up Prussians, Swedes, and a future crown in Westphalia, Davout and Murat pursued Hohenlöhe. On October 28, Murat bluffed Massenbach and Hohenlöhe into surrendering with their 10,000 troops at Prenzlau. Lannes’s V Corps pursued the Prussians to Stettin, where his cavalry advance guard under General LaSalle, following the example of Murat, bluffed the fortress’s garrison of 5,000 men to surrender to his 1600-man cavalry division. The final nail in the coffin of the Prussian army came on November 6 when General von Kleist surrendered his starving and dispirited 22,000-man garrison in Magdeburg to Marshal Ney. In a little over five weeks, the Grand Armée had gathered up 140,000 Prussian prisoners, mostly after October 14. It was one of the most lopsided operational victories in history.55

EYLAU AND FRIEDLAND

The War of the Fourth Coalition did not end when French troops entered Berlin. Despite the scale of the victory, the fact that these monumental successes had not ended the war led to muted celebrations back in France. The war-weariness seen near the end of the French Revolution was again in evidence.56 The battles of the Polish campaigns of 1806–1807 represent both the old and the new. Ironically, the shape of things to come occurred first during the campaign that terminated at the battle of Eylau, a bloody stalemate that left Napoleon without a decisive conclusion to the war of the Fourth Coalition. At Eylau one begins to see the transforming character of the operational art of the Napoleonic War, from short decisive campaigns into those of protracted, attrition warfare. The German military historian Delbrück labeled this approach to warfare as ermattungsstrategie, strategy of exhaustion.57

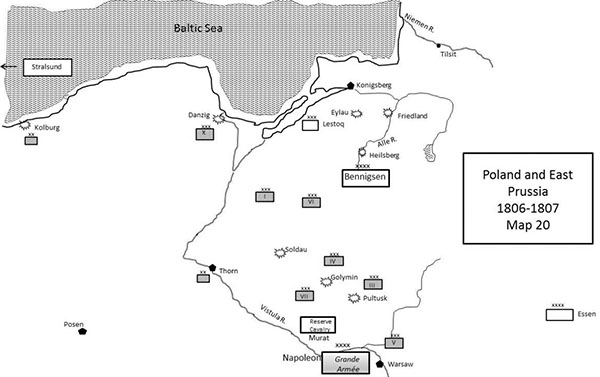

Napoleon’s destruction of the bulk of the Prussian army did not convince the Russians, British, or the Prussian queen, who bent her weak husband to her will, that defeat need be conceded. Napoleon’s initial peace feelers were rejected by all parties. Thus, there were still large Prussian domains in Silesia, eastern Poland, and East Prussia not under Napoleon’s control. He initially delayed the decision to invade Poland, but soon realized that proceeding to the line of the Vistula River had key advantages. Such a position would protect his flanks and his operations to subdue the great fortress of Danzig and secure the Prussian province of Silesia to the south. Nonetheless, he had to peel away forces to garrison the many Prussian fortresses he had seized. One small fortress at Kolberg in Pomerania—defended by an obscure Saxon in Prussian service named August Neidhart Gneisenau—remained defiant, but was masked by light French forces.58

Napoleon decided to continue the offensive by mid-November, when he learned that a Russian army of at least 56,000 had departed in late October to join the Prussian corps under General Anton Lestoq. The French emperor in turn detached a multinational corps composed of Germans commanded by Prince Jerome and assisted by General Dominique Vandamme to secure Silesia as he proceeded east across the Oder River. Davout had already crossed that river on October 31 and, with the surrender of Stettin, Lannes’s corps was ready to cross by the same day. Napoleon’s losses had been light to this point, but nonetheless he knew hard fighting was ahead after the Prussians rejected his peace terms (November 16). Napoleon brought up the second strategic echelon he had mobilized to free his veterans for further campaigning and replace losses. He also denuded secondary theaters of cavalry units, knowing he would need much of that arm in the vast spaces of East Prussia and Poland.59

With the Oder breached, Napoleon’s columns now advanced deep into Poland. A large component of his army (Bernadotte and Soult) had been pulled away by Blücher’s detour to the west and, along with Ney’s VI Corps, these forces were now several weeks away from rejoining Napoleon. He could have waited for them, but decided to push ahead and establish a defensive line along the Vistula River, between Warsaw and Thorn, before the Russians could establish themselves in strength west of that river and to forestall the Prussians from mobilizing the manpower in Pomerania and Prussian Poland to reconstitute their army (see map 20). He succeeded in this daring operational move and Murat and Davout pushed into Warsaw on November 28 as “liberators” to the cheering of Polish citizens. By late November, he had three corps and about half of Murat’s cavalry along the Vistula. The Russian general Bennigsen had been bluffed out of Warsaw.60

The Russians and Prussians attempted a series of local counterattacks trying to catch the French off their guard but these were all repulsed throughout December as the bulk of French army now operated east and north of the Vistula. The Russians commenced a general withdrawal and Napoleon lost contact with them. The end of the month saw Napoleon regain contact and fight three corps-sized battles at Soldau (Ney), Golymin (Augereau), and Pultusk (Lannes). At Pultusk, Lannes was heavily outnumbered until one of Davout’s divisions came up and the Russian counterattack failed—yet again emphasizing the operational durability of the Corps D’Armée. This was enough to cause Bennigsen, now in overall command of his army and Buxhowden’s, to retreat. By the New Year, both armies were spread out in winter quarters throughout the frigid Polish countryside. To the northwest, Napoleon formed a new X Corps under General Victor, who was subsequently captured by Gneisenau’s aggressive cavalry sorties from Kolburg. Napoleon then placed this new X Corps, mostly Germans, under the veteran Marshal Francois Lefebvre.61

Map 20 Poland and East Prussia 1806-1807

Just as the French were settling in for the winter to cover the siege of Danzig, Bennigsen launched a powerful offensive against Ney’s isolated corps. However, he merely pushed it back and then ran into Bernadotte moving up in support on Ney’s flank as that marshal retreated. Bernadotte repulsed Bennigsen’s advance guard and then retreated in order to stay aligned with Ney. Napoleon had many irons in the fire at this point. Jerome was fully engaged in Silesia, Lannes’s corps watched to the east for the arrival of a small Russian army under General Essen, sieges continued along the lower Vistula, and Bennigsen commanded a powerful army of almost 70,000 tough tsarist troops. Nonetheless, Napoleon sensed a chance to destroy Bennigsen and he ordered an all-out offensive against the Russians’ rear and left. Unfortunately, Bennigsen’s Cossacks intercepted Napoleon’s orders and the Russians began to retire to escape the trap. In doing so, Napoleon became strung out and this explains how he came to face Bennigsen’s much larger army on the evening of February 7 just outside the little town of Eylau in East Prussia. He sent orders to Davout to join him (as he had before Austerlitz) but delayed in recalling Ney until the next morning. Bennigsen, though, recalled Lestoq’s Corps at 3:30 a.m. and that officer’s chief of staff, Scharnhorst, recently exchanged, plotted a deft approach march that side-stepped Ney—who was supposed to keep the Prussians away from the battle.62

Napoleon’s haste to come to grips with the Russian army, and perhaps its past performance, led him to overreach. He had made errors in the past, after Ulm and before Jena-Auerstadt, but this was among his most glaring. His chase of the Russians had led him to end up in a cage with a “polar bear” in the extreme conditions of the Polish winter. The two-day icy holocaust of Eylau began late on February 7 and then exploded in a senseless slaughter the next day. As at Austerlitz, Napoleon was outnumbered; unlike Austerlitz, he attacked prepared enemy positions. The battle precipitated an early crisis when Marshal Augereau’s small corps blundered into massed Russian artillery as it emerged out of a blinding snowstorm. Russian cannon obliterated it. To counter this disaster, Napoleon launched one of the most famous cavalry attacks in history, Murat’s splendid troopers superbly mounted on captured Prussian chargers. This charge did not win the battle, but it prevented a defeat. After that, the battle became a bloody back-and-forth engagement as operational echelons from both sides arrived to weigh in on the decision. Davout’s corps, the key to Napoleon’s tactical plan, arrived first and this attack had just begun to bear fruit when Lestoq’s 17,000 Prussians arrived on the scene to give the initiative back to the Russians.63 Just as these measures seemed likely to break Napoleon’s damaged army, Ney’s corps arrived on the scene in the last hours of daylight, causing both sides to cease fighting. Ney captured the essence of the battle upon seeing the thousands of corpses in the snow, remarking “What a massacre, and without any results!”64 Total casualties for the two days of confused fighting totaled over 35,000 and possibly higher, two-thirds of them French.65

Bennigsen, like Robert E. Lee after Antietam a half century later, decided that discretion was the better part of valor, and withdrew the Russo-Prussian army in good order into winter quarters. Napoleon then did likewise after half-heartedly declaring victory. Napoleon knew he had almost been bested and for the first time the luster of his generalship did not shine. In France, dissatisfaction at these seemingly unending wars began to result in serious evasions by would-be conscripts, leading to the French version of the modern draft dodger—le réfractaire. The losses of veterans in the Grande Armée had been grievous, the superb army that marched into Germany the previous Autumn and the best army of his entire career was badly damaged. More and more his army consisted of foreign elements: Poles, Italians, Saxons, Bavarians, and other contingents from the newly formed Confederation of the Rhine. Although the Grande Armée proved itself again in the spring and again in 1809, Eylau can be considered as the engagement that demonstrated the limitations of Napoleon’s method of operational art when faced with a determined opponent unwilling to surrender and willing to trade space, time, and casualties with Napoleon.66

General Lefebvre and his multinational X Corps continued the siege of Danzig and its Prussian garrison. Bennigsen returned to the fray with another unexpected offensive in an attempt to break the siege. Several minor actions convinced him to return to winter quarters. Despite being spread out, Napoleon’s dispositions proved resilient enough to frustrate both Bennigsen’s offensive as well as two subsequent Russian and Prussian amphibious operations meant to aid Danzig in May. At the same time, a breakout by the garrison was attempted, but all these actions were ill-coordinated. The Russians were penned up in their beachhead and the Prussians repulsed. Later, the British and Russian navies evacuated the trapped Russian troops.67

On May 22, Danzig surrendered while Jerome and Vandamme continued to reduce Silesian fortresses. Additionally, the Grande Armée added more enthusiastic Polish troops to its ranks. The Russo-Prussians, instead of conserving their strength, had frittered away their small advantage after the stalemate of Eylau. Now Napoleon’s flanks were secure as the spring campaign season approached; his rested and refitted army was ready for major operations. The Allies initiated things by launching yet another premature offensive against Ney’s isolated corps in early June. Ney again conducted a fighting retreat that blunted the advantage Bennigsen had achieved with surprise. Lestoq, advancing in support, was also rebuffed by Bernadotte’s corps. Further down the Vistula, Masséna, recalled from Naples, contained the forces of Essen on the southeast side of the Polish front. Napoleon again tried to trap Bennigsen by fixing him with the corps of Victor (who had replaced the wounded Bernadotte), Soult, Ney, and Davout (roughly aligned north to south) while advancing on Bennigsen’s open left flank with his operational reserves. These consisted of four divisions of cavalry plus a new reserve corps under Lannes and Mortier’s corps, which had been released from the Stralsund front after the Swedes signed an armistice. Napoleon’s surplus of troops thus formed a ready-to-use second operational echelon. As usual, the cagey Bennigsen withdrew his head from the noose before it snapped shut, retreating through the woods and lakes of East Prussia toward his fortified camp at Heilsberg. Ironically, this was the same ground on which the Russians would suffer a disastrous defeat over a hundred years later at Tannenberg in 1914.68

After a brisk rearguard action at Guttstadt on the Alle River, which now covered the retreating Bennigsen’s right flank, the Russians fell back into their camp at Heilsberg. Napoleon pursued with only two corps and Murat’s cavalry. On June 10, with only part of these forces closed up, Murat and Soult attacked and were repulsed and then counterattacked by Bennigsen. Lannes arrived and stabilized things, but was also repulsed in front of the Russian works. Napoleon’s goal was for these forces to fix Bennigsen, but again that general withdrew. The Russo-Prussian troops withdrew along two axes, Lestoq toward Konigsberg and Bennigsen up the right (east) bank of the Alle. Napoleon, unsure of the axis of Bennigsen’s retreat, pursued with cavalry on both sides of the river, but sent the bulk of his forces due north toward Konigsberg. Bennigsen planned to recross the Alle to cover Konigsberg and join Lestoq. His forces arrived at Friedland on June 13, ejected the French cavalry there, and established pontoon bridges to better move across. Napoleon had directed Lannes to secure Friedland. Lannes arrived very early on June 14 and set up a defensive blocking position. He then notified Napoleon that he had Bennigsen’s entire army facing him. This established the occasion for the battle of Friedland.69

Bennigsen, believing he had isolated Lannes’s Corps, continued to bring his 60,000 men across the river through the narrow streets of the village, but his position was a poor one and Lannes, somewhat similar to Davout at Auerstadt, skillfully fought a nine-hour defensive battle that kept the Russians bottled up around Friedland. Just after noon Napoleon arrived in person followed by 55,000 relatively fresh troops. The long June day allowed him to fight a second battle, shattering Bennigsen’s army, including the use, for the first time, of a mobile massed artillery battery under General Senarmont. Napoleon inflicted almost 20,000 casualties, almost all dead or wounded, while incurring 10,000 of his own. On June 15, Lestoq abandoned Konigsberg to Soult and Davout and joined Bennigsen’s army of refugees as it streamed toward Tilsit. Tsar Alexander had had enough. On June 23, he signed an armistice with Napoleon ending hostilities, and two days later, the famous meeting on a raft at Tilsit on the Niemen River took place between the two Emperors. Alexander joined Napoleon’s “Continental System” of economic warfare against Great Britain and signed a Franco-Russian defense treaty. Prussia was thoroughly humbled, her army limited to less than 45,000 men, the grand duchy of Warsaw carved out of her territory, her western possessions and those of her allies used to create a new Kingdom of Westphalia for Jerome Bonaparte, and her fortresses garrisoned with Napoleon’s troops, and the Napoleonic Empire had reached its pinnacle.70

* * *

The short Friedland campaign proved the Grande Armée and Napoleon again as an unbeatable combination because they reflected the new operational way of war while the Russians remained mired in the past, organized and operating under the rules of the 18th century. Nonetheless, the tactical brilliance of Friedland masked the change in the character of Napoleonic operational art that would soon be in evidence in the last part of the decade. This proved to be the last time that Napoleon would have an asymmetrical advantage over his opponents as they adopted the French system of conscription, corps, and concentration of force. In the meantime, Napoleon’s economic warfare against Great Britain took him down a path that ultimately proved to be his ruin.