THE TWILIGHT OF NAPOLEONIC OPERATIONAL ART

FRANCE 1814 AND WATERLOO

Every campaign plan chooses one path among a thousand…. The mere listing of the essential facts will enable common sense—that is, a mind that is not corrupted—to identify at once what is true and right. Such a mind possesses something akin to musical sense; it easily identifies a false argument as though it were dissonant.1

Carl von Clausewitz, ca. 1820

Carl von Clausewitz opened his operational analysis of Napoleon’s brilliant 1814 campaign with an odd allusion to a musical metaphor, but the idea of dissonance marks a convenient starting point for the end of this study. Clausewitz’s translator, Peter Paret, criticizes this account’s “surprising neglect of politics” and their influence on the campaign.2 Had Napoleon been a bit better politician these campaigns, both the 1814 and Waterloo campaigns might have never occurred. It is hard to understand this failing. By the end of the 1813 campaign Napoleon was beaten and he knew it; so did every soldat and l’enfant in the Grande Armée—a now rather grand title for a spent force. The allies knew it, too.

However, Napoleon the statesman once again decided to see if Napoleon the general could win at the gaming table that which the statesman had squandered.3 He rejected the Allies’ initial peace terms of a return to the “natural frontiers” of France along the Rhine, Alps, and Pyrenees, and then made things much worse on himself by showing how dangerous he remained by fighting brilliantly on the defense and on interior lines as he had in Italy in 1796.4 In doing this he hardened the Allies’ collective resolve when they had begun to quibble among themselves about leaving him in power. As a result, if the quarreling Prussians, Russians, British, and Austrians could agree on anything, it was now that Napoleon should be removed for all time as the head of state of the nation of France. A similar dynamic took place when he interrupted the Congress of Vienna in March 1815 with his escape from exile in Elba by landing in France and marching on Paris. Mirroring this history, then, this book treats these final two campaigns (instead of just the Waterloo campaign) as an operational epilogue rather than to a more in-depth analysis. In any case, both of these campaigns have been analyzed at the operational level in some detail by Clausewitz, among others, and readers are encouraged to examine those analyses in all their power, keeping in mind the ideas expressed so far in this book.5

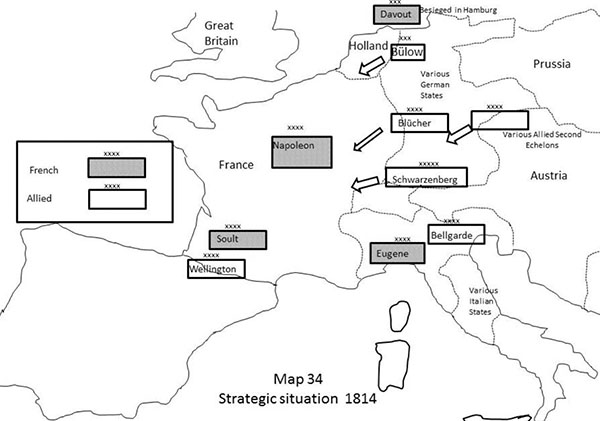

To a certain degree the trajectory toward the operational art went into reverse gear during the campaigns of 1814 and 1815, becoming almost 18th-century affairs when examined from the French perspective. The wars seemed to end where they started, with France surrounded on all sides and with hostile armies threatening her on all fronts, except this time there was no Valmy (see map 34). Also, the coalition he faced had a resolve hardened by the “terrible lessons” Napoleon and France had administered for over 20 years.6 In the opening days of 1814, Wellington advanced with his coalition army on a single line of operation toward Toulouse against Marshal Soult. Viceroy Eugene defended northeastern Italy in a series of rearguard actions, again along a single line of operations against the more numerous Austrians. Marshal Suchet, still undefeated, retreated reluctantly into France, leaving thousands of troops behind in garrisons that would never be relieved. As various Allied forces subdued and surrounded French fortresses, the one-time Marshal Bernadotte cashed in on his promised rewards and conquered Denmark as a means to add Norway to the Kingdom of Sweden.

Map 34 Strategic situation 1814

Finally, Napoleon found himself penned in by several large Allied armies in the region along the Seine and the province of Champagne, campaigning in the dead of winter with an army of never more than about 80,000 troops, most of them teenage conscripts with a sprinkling of veterans and Poles who resided mostly in the Imperial Guard. On the battlefield he often only commanded half that many, and often less, as he confronted the Prussians, Russians, Austrians, and their reluctant “new” German allied contingents. Thus Napoleon was commanding essentially the same number of troops he had at the beginning of his career in 1796, in roughly the same context—conducting an operational defense of a strategic objective on interior lines. However, this time the strategic objective belonged to him and not the Austrians—Paris, not Mantua.7

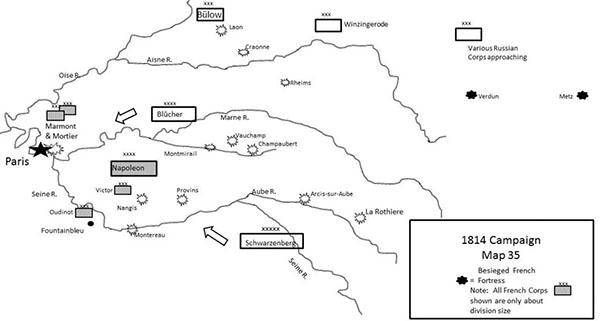

What had changed? Ironically, the asymmetry that French arms had attained during the Revolution vis-à-vis their opponents had flip-flopped. The Allies did not fight in the 18th-century style, even though Napoleon gave them a run for their money; winning many of his battles in the winter countryside of the Seine, Marne, and Aube river valleys (see map 35). Whereas Napoleon fought with an 18th-century-style force, the Allies opposed him with army groups. The situation recalls the waning months of the American Civil War, when the tactical excellence of Lee and Johnston availed them nothing against Grant and Sherman. It was now the Allies who had the grand armies composed of hardened veterans, experienced generals, motivated by an inflamed nationalism. And they had the numbers. Against Napoleon’s mid-sized army they initially advanced united with Blücher commanding nearly 60,000 troops and Schwarzenberg commanding over twice that many. Unlike Napoleon they had large operational echelons approaching the theater from the northeast numbering another 60,000 or more (principally the corps of von Bülow and Winzingerode).

The Allies made one clear operational error and Napoleon made them pay for it when they separated after defeating him early in February 1814 at the battle of La Rothiere. Napoleon, badly beaten, was inclined to accept their revised peace terms of a return to the status quo ante bellum of France in 1789 (peace negotiations continued throughout the period), but could not resist his good fortune when Blücher let his army get strung out on the northern line of approach to Paris. He administered three tactical defeats against their isolated corps—at Champaubert, Montmirail, and Vauchamps (February 10–14)—which sent the Prussians reeling to the north, toward their approaching reserves. But true to form the Prussians retained their cohesion. Napoleon, as in 1813, had little time to pursue them as the large army group under Schwarzenberg (150,000) approached from the south. He managed, with a few sharp actions, to bluff it into a retreat to a safe distance south of the Seine. However, if all this reminds one of the Reichenbach-Trachenberg dynamic in 1813 with fewer Allied victories, then one is thinking along the correct lines. Napoleon’s tactical victories had no meaning as long as the Allied armies remained large, operationally durable, and “in being.” Worse, as mentioned, the French Emperor’s tactical victories fortified their resolve to accept no peace other than one that involved his abdication.8

Map 35 1814 Campaign

= Besieged French Fortress

= Besieged French Fortress

Note: All French Corps shown are only about division size

Predictably, Napoleon attempted to turn north and finish off Blücher north of the Marne River. That March, the bloody battles of Craonne (March 7) and Laon (March 9–10) showed that Napoleon could still lose as well as win, and expend his hard won advantages by further diminishing the few veteran troops available to him. Napoleon managed one more tactical victory, at Rheims, where he annihilated the corps of the émigré General Louis de St. Priest on March 13. However, his casualties had been so severe that month that he took the extraordinary expedient of proceeding east to add the garrisons of fortresses like Metz and Verdun to replace these losses. The Allied armies under Blücher and Schwarzenberg advanced in concert on Paris, ignoring Napoleon’s attacks on their communications and his maneuver to the east. Napoleon had left Paris to the protection of the weak corps of Marshals Eduoard Mortier and Auguste Marmont (of Salamanca fame) and his brother Joseph. This gambit failed. Joseph, as usual, panicked; Marmont went over to the enemy with his entire corps; and Mortier rebelled along with Napoleon’s other lieutenants in the so-called “revolt of the marshals.” Napoleon found himself with no capital, no government, and only a small army composed mostly of his faithful guards at Fontainebleau. On April 6, he faced the inevitable and abdicated, going into exile on the small island of Elba in the Mediterranean.9

Napoleon’s defenders often imply in their work that “if only” Joseph had not panicked, Marmont had not betrayed his old friend or the marshals had remained more resolute, that Napoleon might have prevailed in retaining his throne, or perhaps getting a regency established for his son under the Empress Marie Louise. However, these speculations ignore the facts of Russian, Prussian, and British paranoia about Austria (whose Hapsburg Princess might be regent in Paris), the claims of the Bourbons, and of numbers. Also, if the Allies could survive a Borodino or a Dresden, they could certainly survive more Vauchamps and Rheims. Napoleon, on the other hand, could not survive many more La Rothieres or Laons. His campaign to exhaust the Allies’ will using the defense had failed—it failed nobly—but it had failed. There was no “miracle of the House of Bonaparte.”10 However, it impressed Clausewitz, who, it seems, decided once and for all the defense was the stronger form of war, although his inclination on this matter had been greatly supported during the 1812 campaign in Russia.11

SOME COMMENTS ON WATERLOO

The Waterloo Campaign in 1815 reflected the same trends noted in the previous section—the Napoleonic cycle and operational art in reverse. Although Napoleon put together something of a new Grande Armée, L ‘Armée du Nord (Army of the North), it was missing much of the original’s “equipment.” Marshals Lannes, Bessieres, Murat, and, perhaps especially, Berthier, were no longer there. Davout was deemed too valuable to spare and left in Paris as the minister of war. Finally, the troops themselves, many of them veterans from past wars, had little time to coalesce and train together as had the original ticket along the English Channel from 1803 until 1805 when it marched, nearly 180,000 strong, off to glory at Ulm and Austerlitz 10 years before.12

Another indicator of the reverse trend reflected by the 1815 campaign resides in the area of command and control. The Allied force immediately facing Napoleon had no unity of command; there was no overall army group commander. Blücher and Wellington cooperated more along the lines of Eugene of Savoy and Marlborough, operating in concert in a 19th-century version of early 18th-century military esteem. Of these two armies, Blücher’s army seemed the more modern in retrospect, a veritable Prussian Grande Armée composed of four large combined arms corps with 30,000 men apiece. Also, he had the incomparable Gneisenau at his side as chief of staff with Scharnhorst’s acolytes (including Clausewitz) seconding all his corps commanders. Wellington’s army, on the other hand, looked much like the sort of force Marlborough often took to war a hundred years earlier at slaughters like Oudenarde and Malplaquet, a coalition of disparate European contingents built around a corps of British “shock” troops, as Winston Churchill often characterized them in his famous military biography.13 On the other hand, these two generals (three if we include Gneisenau) had proved Napoleon’s most inveterate and dangerous opponents, and it did not bode well for him that the Allies had wisely placed them in close proximity to each other as their first operational echelon. However, Napoleon had little choice other than to attack them first given their proximity to Paris.

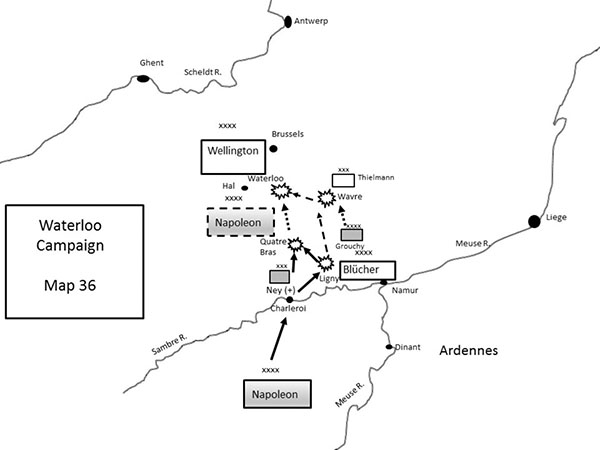

Perhaps the most positive reflection of the operational art to be found in the Waterloo campaign, at least on the French side, involved the fact that Napoleon could bring even the ghost of the Grande Armée with such rapidity against the Allies, themselves still mobilizing, and shatter their strategic equanimity. It is captured best in this passage from the West Point Atlas of the Napoleonic Wars: “This concentration remains one of the great military feats of history—all the more so in that some of these corps completed their organization as they marched.”14 However, Napoleon soon ran afoul of the frictions of war, despite the strategic surprise occasioned by his sudden arrival in mid-June 1815 at Charleroi at the hinge between the Allied armies under the Duke of Wellington and Field Marshal Blücher (see map 36). The Allies duly concentrated their individual armies prior to attempting to join forces, but on June 16 Napoleon and Marshal Ney fought Blücher and Wellington, respectively, at Ligny and Quatre Bras. As at Jena and Austerstadt, one corps wandered between both battles without participating in either, but the result was not so fortuitous. Ligny was another in a long line of almost-great Napoleonic tactical victories. However, the Prussians, though forced to retreat, did not conform to Napoleon’s wish that they pull away from Wellington and maintained pace with that general and his army.15

Quatre Bras had not been so much a victory for the French as a stiff British rearguard action. Also, Napoleon lacked the resources of former years to pursue his enemies à outrance as he had done after Ulm, Jena, and Auerstadt. He did assign the mission of pursuing Blücher to the newest marshal Emmanuel de Grouchy, however, Grouchy’s tools were limited and both he and Napoleon misjudged Blücher’s line of retreat. By the time Grouchy found Blücher’s rearguard under Generals von Thielmann and Clausewitz at Wavre on June 18, the other three corps of the Prussian army had already marched off toward Waterloo and Napoleon’s open right flank. Meanwhile, at Waterloo (or Mont St. Jean) on June 18, Wellington fought another of his signature defensive battles—although its results looked more like Albuera than Bussaco, at least until the Prussians showed up.16 When Blücher’s first corps arrived just after 4:00 p.m., they found Wellington hard pressed but standing firm. From that point on, Napoleon fought a losing gambit, his best chance being to shatter Wellington’s army and fight Blücher’s to a standstill, followed by a retreat in the manner of Leipzig with his army in relatively good order for a reunion with Grouchy. Instead, the army that was shattered was his own, thus capping his military career with his most disastrous tactical defeat.17

Map 36 Waterloo Campaign

Only on the day of battle at Waterloo did the campaign shed some of its 18th-century flavor as the Allied army group, sans an overall commander, came together in the afternoon, increasing in size to almost 140,000 effective combatants to Napoleon’s 72,000 troops (these numbers do not include deductions for casualties throughout the day). Initially Napoleon’s 72,000 faced only Wellington’s 68,000—although commentators have noted that Wellington might have had 85,000, which more nearly approximates the correlation of forces for the French versus the Allies at Austerlitz. Nonetheless, Blücher’s message of promise to support Wellington caused that general to take the luxury of protecting his far right flank with 17,000 troops near Hal. However, with the arrival of the Prussians the campaign’s reflection of the later Napoleonic operational art returns, except with the Allies better mimicking the Napoleonic method of concentration of superior force at the decisive point than the French.18

Comparisons with Austerlitz also fall short when these numbers and how they came to be are examined more closely. They remind one more of Napoleon at Friedland, with Napoleon in the role of Bennigsen, fighting a losing engagement as fresh echelons arrived to overwhelm him.19 Napoleon was defeated by a mechanism that looked a lot like his own masterpieces. Blücher’s army served as the masse de manoeuvre sur la derrier (maneuver mass on the rear) against Napoleon’s flank and line of retreat. Also, it was Blücher’s cavalry that executed the pursuit à outrance after the battle, not the French.20

Another comparison might be with the French maneuver at Bautzen, on a bit of a smaller scale at Waterloo, again with the roles reversed and Blücher as Ney, except that the flanking force was more effectively deployed and led. This last can be attributed to the hard work of another Prussian general staff product, Baron von Müffling. Müffling served as the often unsung liaison officer who took effective control of the deployment of Blücher’s corps as they arrived on the field of battle. Jomini labels this sort of deployment “grand tactics,” but in fact it is the reflection of a mature operational art on the part of the Prussians.21 Although much ink has been spilt about “who” deserves the credit for the victory, all can surely agree that it must go to the collective, to the Allies. The point to emphasize here is that Napoleon and his army now looked like his former opponents while his opponents looked like the earlier French—the roles had reversed, both in terms of size and maneuver.

Ultimately, the campaign, as Own Connelly writes, was a “glorious irrelevance.”22 The Duke of Wellington reputedly characterized it a “social event” something “like a ball: full of interesting incidents.”23 Had Napoleon won the victory it is more than likely it would have been another of his many “pyrrhic” victories, the most recent being Ligny.24 First, given the events of that day, in all likelihood Napoleon could not have pursued the Allies even had they been forced to retreat on divergent line from the Prussians. Wellington would have fallen back on his reserves and Blücher on his, as had happened so many times in both the 1813 and 1814 campaigns. The durable operational army created by the Napoleonic crucible now lay in the Allies’ possession. Additionally, the second echelon of Allied armies was advancing on all fronts and numbered nearly a half million more troops, under the same resolute leaders as before: Schwarzenberg with Radetzky at his side and the ubiquitous Barclay de Tolly.25 It was only a matter of time, not outcome, and thus Waterloo can be seen as a blessing that prevented the further effusion of needless blood. That was how it was regarded at the time, and the collapse of France so quickly afterward confirms that the spirit of 1794 was no longer there to defend La Patrie en danger if it meant endless war.

* * *

The twilight of Napoleonic operational art settled on Europe as military professionals tried to make sense of what happened.26 Operational art could go only so far once the tyranny of distance and its effects on logistics and command and control limited what the new peoples’ armies could do. The energies that had overcome the obstacles of 18th-century military practice were no longer inflamed by the mighty exertions that the Revolution, Napoleon, and nationalism demanded. However, as the sun set on Napoleonic glories, the tools for the next generation of operational artists were even then being forged in the diabolical workshops of men: the steam engine, the railroad, rifled artillery and muskets, and the telegraph. These workshops soon became known as factories, because of their mass production, such as Eli Whitney’s famous gun factory. In them would be forged the tools for a new round of the violent development of the operational art that came to destroy the old order again—in 1914.