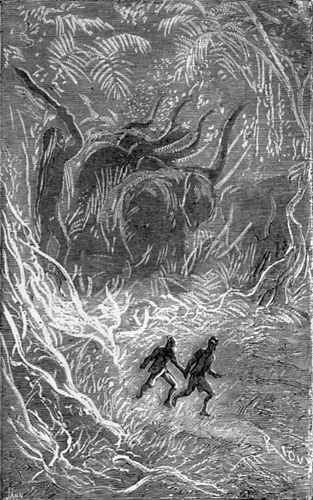

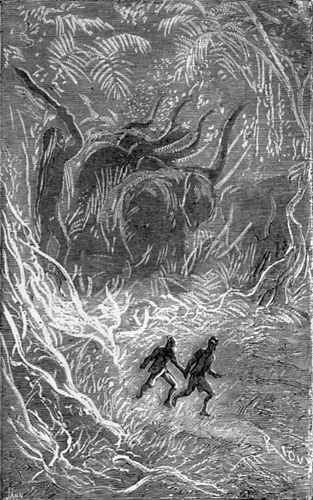

Figure 3-1 Axel and Lidenbrock flee from the sight of the shepherd and his herd of mastodons: “Immanis pecoris custos, immanior ipse!” Édouard Riou, public domain.

Benjamin Eldon Stevens

Jules Verne’s novel Journey to the Center of the Earth (1864a [Journey]) makes frequent and meaningful references to Greek and Roman classics, paying special attention to the Latin language and its literature.1 In this chapter I argue that Journey’s engagement with the Roman poet Virgil—via quotations, allusions, and a deep structural parallel to Virgil’s epic poem, the Aeneid (ca. 19 B.C.E. [Aen.])—exemplifies how modern science fiction (SF) may be read as drawing on classical traditions in order to articulate master narratives of modern science. In general, the ancient classics are displaced from their previously privileged position of “knowledge,” becoming instead “mere tradition,” while “knowledge” is limited to the results of modern scientific practice (or, as in Verne’s case, science writing).2 In Journey in particular, Verne—described by his publisher J.-G. Hetzel as “the man of perpendiculars”—replaces Virgil’s unsystematic cyclical cosmology (as described to Aeneas by the ghost of his father, Anchises) with the nascent science of geology and its consequences for a linear model of human history, including prehistory. Whereas Virgil’s hero encounters figures from his own past from whom he may acquire knowledge about an ideal future for his people, Verne’s hero experiences a vision, even a sort of “epiphany,” of a far more distant, depersonalized past—a prehistory—that is said by the new scientific narrative to be shared by reader, author, and characters alike.3 In this way, following a sort of perpendicular deviation from ancient epic, Journey offers an image of the “hero” redefined as modern scientific man.

At the same time, as it replaces and displaces the classics, Verne’s narrative may also be read as offering a critique of modern science, in part by showing appreciation for what science does not seem to capture adequately. In this connection, Latin in general and Virgil above all are represented as natural means of expressing personal feeling, especially the “romantic” feelings of wonder, affection, and love. In the world envisioned by the novel, Latin is simultaneously the language of scholarly communication and the language of personal expression. Relatedly, the novel’s narrator understands Latin in terms that would distinguish “science” from “poetry.” This evaluative distinction interacts with the novel’s general engagement with the classics in complex and interesting ways.

In what follows, I attempt to justify this reading of Journey’s classical receptions by focusing on the novel’s three full quotations from Virgil. (Some other references to ancient material are discussed in the notes, and all are gathered in an appendix to this chapter.) Although the third quotation is perhaps the most important for the novel’s reception of classical material overall, since it occurs at an especially climactic moment in the story, all three together suggest ways of understanding Vernes’s engagement with Virgil, Latin, and the classics, and so may serve to organize my argument. Above all, I hope to show how productive it can be to read modern SF as a kind of classical reception that draws on classical tradition to articulate and to complicate its own master narratives.

Journey’s first quotation from Virgil occurs when the narrator, the journeyman scientist Axel, and his uncle, Professor Lidenbrock, are leaving Reykjavik (where they have stopped overnight) for their overland journey to the entrance into the earth’s depths (ch. 11).4 As they leave, they are bidden goodbye by one of their hosts, Mr. Fridriksson, with, as Axel puts it, “that line from Virgil that seemed ready-made for us, voyagers uncertain of the way: Et quacumque viam dederit fortuna sequamur” (Aen. 11.128).5 In English, the Virgil is: “And let us follow whatever road fortune has given!” The quotation is apt, and its placement at the end of the chapter produces some dramatic effect, somewhat in the manner of a serialized novel. Likewise, it may give an insight into Axel’s feeling, melodramatic (even if it is accurate as a prediction) in combining the personal with the grandiose. The fact that such a “romantic” feeling is somehow best expressed in Latin is emphasized both at this moment and by the extended scene in Reykjavik. At the moment of goodbye, whereas Professor Lidenbrock could express his warm thanks to their host “in Icelandic,” Axel himself “strung together a cordial farewell in [his] best Latin.”6 Previously in the Reykjavik scene, Mr. Fridriksson is introduced as a “humble scholar [who] spoke only Icelandic and Latin: he came and offered his services in the language of Horace.” Therefore Axel “felt that [they] were bound to understand each other.” Axel’s feeling that Latin allows for solidarity is emphasized: “He was in fact the only person I could converse with during my entire stay in Iceland”; as a result, Axel declares Mr. Fridriksson is “charming” and his conversation “quite precious.”7 It seems then that, by the end of their brief stay in the capital, not only is Latin Axel’s only means of communication with anyone, but the language is also positively charged with warm feeling.

Readers familiar with the Latin classics may not be surprised that Axel’s standard of comparison is poetry; most often—and at the most important moments—Virgil. A crucial aspect of Journey’s engagement with the classics as they are implied in (Virgil’s) Latin is thus a sort of tension between Latin as a language of communication among scholars, focusing on accurate and enduring description in scientific terms, and Latin as a vehicle for personal expression, which by contrast conveys a vivid impression in a particular moment. For convenience, we may call these two modes “scientific” and “romantic.”8 Although during the Reykjavik scene Axel refers to the Roman poet Horace, a contemporary of Virgil’s, two other moments help make clear Axel’s feelings that Virgil is the high point of Latin and, as a result, that Latin is especially well suited to personal, “romantic” expression. We will see that Lidenbrock’s understanding of Latin is the more “scientific,” although the two are not completely opposed to each other.

At the first of the two moments in question, Axel offers his appraisal of the technical terms of his uncle’s primary area of scientific interest, mineralogy.

Now, in mineralogy, there are many learned words, half-Greek, half-Latin, and always difficult to pronounce, many unpolished terms that would scorch a poet’s lips. I do not wish to criticize this science. Far from it. But when one is in the presence of rhombohedral crystallizations, retinasphalt resins, ghelenites, fangasites, lead molybdates, manganese tungstates, zircon titanites, the most agile tongue is allowed to get tied in knots.9

The context for this appraisal is Axel’s extended first description of his uncle, focused here on his “slight pronunciation problem.”10 For our purposes, however, the most interesting feature of this paragraph is Axel’s insistence that his dislike of the “learned words,” what we could call “scientific terminology,” is distinct from his positive feelings towards the learning or science itself. Axel is concerned, not with scientific precision, which he grants, but with these terms’ aesthetic effect—what he refers to as their “poetry.” We may therefore say that his dislike of the terms is not scientific but linguistic and aesthetic: there is something regrettable about “half-Greek, half-Latin” forms, the problem being, again, that such forms do not seem “poetic.”11 Since Axel makes this clear in Journey’s first section, and since the novel is entirely his narration, the whole novel may be taken as proceeding with this distinction in mind.

The distinction between “scientific” and “poetic” language is emphasized in the second of the two moments currently in question. Axel and Lidenbrock have just succeeded in decoding a cryptogram in runic writing discovered between the pages of Snorri Sturluson’s Heims-Kringla.12 This decoding process is what precipitates the journey: as Axel puts it, “these bizarre forms . . . led Professor Lidenbrock and his nephew to undertake the strangest expedition [of] the nineteenth century” (Journey 9). Once the message has been transliterated from runic letters to Roman letters and then read in the right order, in Lidenbrock’s view “nothing is easier” than identifying it as Latin.13 As Lidenbrock reasons it, the writer of the cryptogram, one Arne Saknussemm,

was an educated man. Now, when he was not writing in his mother tongue, he must naturally have chosen the language customarily used amongst educated people of the sixteenth century—I refer to Latin. If I am proved wrong, I can try Spanish, French, Italian, Greek, or Hebrew. But the scholars of the sixteenth century generally wrote in Latin. I have therefore the right to say, a priori, that this is Latin.14

There is, then, a very real way in which the journey is inspired by knowledge of Latin, particularly as Latin is regarded as having been the language of scholarly communication.15

Also important for our purposes is how the Latin is evaluated. Axel is surprised, even dismayed, by his uncle’s deduction about the language of the inscription: “for [his] recollections of Latinity revolted against the pretension of this assemblage of uncouth words to belong to the soft tongue of Virgil.”16 In Axel’s mind, in contrast to Virgil’s poetry, the cryptogram is “bad Latin” (mauvais latin). This negative evaluation helps emphasize how Axel’s image of Latin is “classical” indeed or, more precisely, “classicizing”: in Axel’s view, Latin is a language of poetry and thus a cultivated vehicle for heartfelt self-expression. In this way the novel links the “soft tongue” of Virgil with a narrator whose interest in modern science is in certain ways secondary to his sentimentalism. Again, this distinction between “scientific” and “romantic” or “personal” plays out in language. Axel thus comments on his feelings for Lidenbrock’s godchild, the object of Axel’s affections: “I adored her—if, that is, the word exists in the Teutonic language.”17 Likewise, when Axel is made to test out his uncle’s theory about the arrangement of letters in the cryptogram, he writes, “I love you so much, my darling Graüben!” He writes this “immediately” and “like a love-sick fool,” as if without complete control over his action.18 In part this is a gleeful depiction by the very French Verne of a quite un-German and un-scientific immodesty. From such a character we might well expect spontaneous expression of emotion, and a “soft tongue” like that embodied in Latin poetry serves as the appropriate vehicle.

Evaluation of the language and of its appropriate use is also evident in Professor Lidenbrock. In contrast to Axel’s “romantic” view, Lidenbrock represents an image of Latin as mainly “scientific,” the lingua franca of scholars. Since Lidenbrock is something of a comic figure, his image of Latin’s importance may be mocked as out of date: Latin as a means of learning is ascribed to the sixteenth century, whereas modern scientists of the nineteenth century, including Lidenbrock himself, communicate in modern languages. There would seem to be no question in the novel of Latin’s return to international importance.19 We may also note that Lidenbrock nowhere seems concerned, as Axel is, with questions of style: for him the Latin of the cryptogram is, like the lingua franca of an earlier age, a means to an end. In a similar vein, although Axel may expect his uncle to be able to “produce pompously from his mouth a sentence of Latin majesty,” this would seem to be a matter of his general admiration for his uncle’s knowledge of all things (“my uncle was an authentic scholar—I cannot emphasize this too much”; Butcher 2008: 5), including a great many languages, rather than specific to “Latinity” as such.20 For Lidenbrock, then, Latin is not so much necessarily “classical,” much less the property of Virgil in particular, as it is “historical,” merely one language among many and thus to be understood like any other.

In the several moments we have considered so far, Journey figures Latin complexly, as both a language of precise, professional, “scientific” description and as a vehicle for evocative, personal, “romantic” expression. With Latin and Virgil standing in for the classics more generally, the classical tradition is likewise a matter of complex presentation: the classics are a matter of significant common knowledge, even as “tradition” is yielding to scientific “knowledge.” Conversely, the tradition is also a matter of personal expression, even as that expression—and the genre of the novel—is gently mocked. Complexity of tone aside, the general implication is that Latin and the classics have changed in status from “classic” to “(merely) traditional.”

Having developed a first impression of Journey’s complex image of Latin, Virgil, and the classics, we may turn to the novel’s second and third quotations from Virgil. The second quotation shows that Verne’s appreciation of Virgil is combined with serious departures from him, while the third represents a dramatic and consequential departure indeed, at precisely the moment we might expect: the deepest and most climactic part of the journey. The second quotation occurs when Axel, Lidenbrock, and their Icelandic porter Hans, who have all spent the night at the bottom of the chimney of the dormant volcano Snaeffels, begin the descent proper, moving into what would be utter darkness if not for their “electric torches.” Axel is disturbed by losing sight of the sky. But soon he is able to say to himself facilis descensus Averno (quoting Aen. 6.126): “easy [is the] descent into the Underworld.”21 This quotation serves to express Axel’s renewed good humor and even delight, emotions he feels “in spite of” himself, at two things. Most immediately, he responds to the physical ease of the descent: “we were able to simply let ourselves go on these inclined slopes, without taxing ourselves. It was Virgil’s facilis descensus Averni,” or “easy way down into the Underworld.”22 More generally, he is taken by the spectacle provided by this first truly underground experience.23 As in the novel’s complex image of Latin, Axel’s response at this moment combines the scientific and the romantic, blending the mineralogical, the domestic, and the supernatural:

The lava, porous in places, was covered with little round bulbs; crystals of opaque quartz, decorated with clear drops of glass, hung from the vaulted ceiling like chandeliers, and seemed to light up as we passed. It was as if the spirits of the underground were lighting up their palace to welcome their guests from the Earth.24

The last sentence especially gives a sense of the ancient underworld, as it was populated with “spirits.” In this connection, it matters that the quotation from Virgil occurs in the Aeneid just prior to the entrance into the underworld.25 For our purposes, it is also important that Axel does not complete the quotation. In Virgil, facilis descensus Averno is only the beginning of what is said by the Sibyl, a prophetic figure, to Aeneas once he has made clear his intention to journey below (Aen. 6.126–131).26 “The way down into the Underworld is easy,” says the Sibyl, for “night and day the doorway of black Dis stands open.” But then she continues: “But to call your step back, and to fly out to the air above, this is the work, this is the labor.” Moreover, successful return has depended on truly exceptional circumstances, including outstanding virtue or, better, divine ancestry: “A few, whom Jupiter loved well or whose own ardent virtue carried them up to the upper atmosphere, those few born to the gods could do it.” Certain of these factors apply to Aeneas: he is protected by Jupiter from the worst of Juno’s anger, and he is a son of Venus.

In contrast, it would seem that none of these factors could apply to Verne’s voyagers. A prior question is whether they should: whether it is useful to read Axel’s quotation somehow in the light of its original context and, therefore, to think of what follows facilis descensus Averno as somehow “missing” or “suppressed.”27 I think that Journey’s deep engagement with Virgil requires us to do so: not so as to impose Aeneas’ experience on the voyagers, but as a way of describing the effect of the relationship between the two works more precisely. Given Virgil’s place in education at the time, Verne himself would certainly have known the original context, and it is likely that his intended readers, too, could be expected to recognize the famous passage. Axel’s quotation thus has the effect of introducing a certain ironic suspense or foreboding. Will Verne’s modern heroes, like their ancient predecessor, face a difficult ascent? If so, will the difficulty be of a similar sort?

With these questions we touch on an aspect of the Aeneid that has long puzzled readers: Aeneas’ ascent does not seem to be “difficult” at all; in fact, he seems to leave the underworld with ease. His return to the surface is, however, not therefore straightforward, and the complexity may help us understand Verne’s appropriation more deeply. In Virgil, there are two gates by which Aeneas could return to the surface, each with a different implication:

|

There are twin gates of sleep, of which the one is said to be horn, through which easy exit is given to true shades, |

|

|

while the other has been made to shine with gleaming ivory, |

895 |

|

but [through it] the shades send false dreams to the heavens. To these, then, Anchises followed his son and the Sibyl with words and sends them out through the ivory gate.28 |

|

As noted, Aeneas simply exits, and once out he seems, also simply, to “return to his ships and companions”;29 in the six books of the Aeneid that follow this moment, there is no reference to the matter of the gates or to any particular “difficulty.” We may nonetheless ask whether anything is implied by Aeneas’ exit being through the gate of ivory, reserved as that is for “false dreams.”30 It could be that Aeneas, being no kind of shade (i.e., spirit of the dead), simply must use that gate.31 In contrast, it would seem unsatisfying were the gates merely a way for Virgil to suggest “the time of night.”32 While insisting, then, on some meaning, we may need to conclude, as Austin puts it, not only that “no one knows the full implication” of this exit, but also that “[t]here is no means of knowing what deeper significance [Aeneas’ exit] held in Virgil’s mind for Aeneas’ experience in the Underworld.”33

For our purposes, it is enough to be able to think of Aeneas’ exit as suggesting something profound about ascent and the underworld, something that may affect our understanding of how the Sibyl’s prophetic utterance to Aeneas (facilis descensus Averno. . .) is appropriated by Verne. If the Sibyl is not to have been wrong in her confident description of “difficulty,” then we may wish to understand her as having spoken metaphorically, focusing on how the underworld affects the hero. In particular, Aeneas cannot easily “leave” the underworld in emotional terms. He spoke there with his father, whose death he calls “the most grievous” and surprising event on his voyage to Italy (Aen. 3.708–713), and he sought in vain to speak with his beloved Dido, whose death half-surprised him and must be laid in part at his feet (6.450–476). Emotionally, Aeneas is consigned to a kind of hell; he carries it with him.34 The hero is changed by his journey.

We may now ask whether Verne’s explorers are affected by their ascent in a way that makes them comparable to Virgil’s deeply troubled hero. What is implied by the journey’s proceeding under the sign of Aeneas’ “easy descent and difficult return”? By contrast, what is meant by Axel, Lidenbrock, and Hans returning to the world above as they do? Echoing Virgil’s “true dreams” and “false shades,” it has seemed to Verne's readers that parts of Axel’s experience under the earth are framed in ways reminiscent of dream-narratives or altered consciousness. For example, Axel falls asleep just before the descent proper (Journey ch. 17). Is the journey under the earth therefore a kind of “dream”? Similarly, just before the final moment of the ascent, Axel loses consciousness (ch. 43). Is his return to the surface world a sort of “waking dream”? In the terms provided by Virgil, would such a dream be “true” or “false”? Whatever the answer, there is thus a way in which the voyage is under the sign of “dream,” and so may be linked to Virgil’s dream-gates.

By some contrast, although in Verne the ascent itself is rather longer and a matter of great physical difficulty indeed, the result would seem to be wholly positive. The voyagers ascend on a “raft” raised by a column of water caused by eruption of an active volcano, Stromboli.35 The violent activity of Stromboli stands in implicit contrast with the dead chimney of Snaeffels on the initial descent, forming a ring-structure that gives vivid closure to the journey into the earth.36 Verne describes Stromboli in evocative terms: it belongs to “the Aeolian archipelago of mythological memory, [and is] the ancient Strongyle, where Aeolus held the wind and storms in fetters” (Journey 213). While the journey’s exit- and end-points therefore differ markedly from Virgil’s, their explicit association with Aeolus forms a link to Aeneas’ first experience in the Aeneid, a catastrophic storm rained down by none other than Aeolus and his winds (1.81–156). By linking his voyagers’ exit from the underworld to Aeneas’ very first experience, Verne effects a precise sort of reversal, in which the ancient epic, storehouse of “mythological memory,” is rewritten to reflect a new, modern, scientific understanding of the world and “underworld.” In particular, the latter seems now to be only literally “the world below,” not primarily a symbol of something figuratively deeper.37 It would seem, then, that the very concept of a “journey” as well as its consequences have been transformed.

We may therefore conclude this reading of themes suggested by Journey’s second quotation from Virgil by saying that what is for Aeneas a real source of danger is for Axel and his companions a matter of immaterial “mythological memory” alone. Attributed as it is to Axel, the reference to Aeolus adds a note of romance—and that may be all. In strong contrast to Aeneas, then, Verne’s characters are, at this point, not heroes of the sort populating ancient epics: they are not subject to laborious wandering caused by capricious gods. Although they are surprised at their destination, they accept their “fate” as being the result of rational causes; and importantly, that destination is not final, for they are able to return home. Whereas the narrator of the Aeneid asks, rhetorically, “Is there such great anger in the hearts of the gods?” (tantaene animis caelestibus irae; 1.11), the narrator of Journey, Axel himself, is in the very different position of reporting on causes he has already discovered or experienced. For that matter, he reports on them from home, indeed from a bourgeois sort of domestic bliss, accepted as a member of an international scientific community and with his beloved Graüben by his side. Again, then, Verne’s voyagers may have more in common with an ancient explorer like Herodotus, interested in firsthand experience (autopsy) and rational explanation (logos), than with the sorts of “heroes” whose mythological misadventures Verne actively rewrites.

From this perspective, Axel could be the sort of man called “blessed” by Virgil in an earlier poem, the Georgics (c. 29 B.C.E. [G.]): the sort “who was able to understand the reasons for things” (qui potuit rerum cognoscere causas; G. 2.490). This sort of rational understanding means conquering the (irrational) fear of death: as Virgil puts it, such a person has “ground the groan of greedy Acheron,” a river in the underworld, “beneath his feet” (subiecit pedibus strepitumque Acherontis avari; 2.492). Although the river Acheron is in a way metaphorical, the image here also has a certain material force: lying behind Virgil's lines in the Georgics is Lucretius’ poem De Rerum Natura (from the second quarter of the first century B.C.E.), which argues that death should not be feared, since it cannot be a new state of being (much less the literal underworld of the epic tradition) but is the end of all conscious experience. From this perspective, there would be, then, something about Axel, and about the world of his novel, that is less Virgilian and spiritual—certainly less “Aeneidic,” as we may call the quality of having one’s question about causes, precisely, go unanswered (Musa, mihi causas memora; Aen. 1.8)—than Lucretian and material, befitting a rational modern scientist.38

None of this means that everything Axel reports is credible. He himself expects that his report will meet with disbelief: it is “a tale which many people, however determined to be surprised at nothing, will refuse to believe. But I am armed in advance against human scepticism.”39 As we have been seeing, that skepticism may be read as arising in part from the way that Journey figures “traditional” ways of knowing, including the ways represented by the Greco-Roman classics, as newly subordinate to scientific practice, which alone is able to produce “knowledge” as such. If Axel and his fellows went under the earth in a manner reminiscent of ancient epic heroes, after their return—and as a result of Axel’s own narration—they are something decidedly new: science-heroes.

Journey may thus be read as a sort of Bildungsroman, a “coming-of-age novel,” in which the young scientist discovers, among other things, his own maturing capacity for “science.” As we have seen, however, that capacity is not completely separate from Axel’s “romantic” or “poetic” inclinations, which are expressed partly in terms drawn from his beloved Virgil, among other Latin authors. Axel thus figures the scientist as a sort of rewritten epic hero, following in ancient footsteps even as he seeks to offer modern scientific explanations for what he sees. This combination of structural similarity and profound epistemological difference is perhaps clearest in the moment surrounding the third quotation from Virgil. In particular we will see how Verne replaces Virgil’s cyclical cosmology and image of divine “prophecy” with the nascent science of geology and its implications for linear history, including human prehistory. In a related way, the ancient epic’s sense of emotionally unfulfilling duty and death is replaced by a modern, “romantic” novel’s sense of life and love as comedy. Finally, the third quotation also serves to emphasize further the complex literary history that lies behind Verne’s reception of Virgil.

At the journey’s deepest point, Axel reports that he followed his uncle’s excited gaze:

I looked, shrugging my shoulders, determined to push incredulity to its furthest limits. But struggle as I might, I had to give in to the evidence. There, less than a quarter of a mile away, leaning against the trunk of an enormous kauri pine, was a human being, a Proteus of these underground realms, a new son of Neptune, shepherding that uncountable drove of mastodons! Immanis pecoris custos, immanior ipse! “Immanior ipse” indeed!40

Before considering the Latin, it is worth noting that the passage insists on the sort of spatial limits characteristic of Verne, as well as on the significance of numbers, as if to emphasize “scientific” observation. In the French there is, however, also a pun between Axel’s “looking,” regardai, and the monster’s “guarding,” gardai: the pun serves as a first indication of how Axel and the guardian constitute each other, the one observing and the other observed. However disparate, the two are thus made to “double” each other: in that connection, Axel’s reaction is caused in part by the shock of recognizing something in the guardian that—unthinkably, uncannily—resembles something in himself;41 see Figure 3-1 for an evocative illustration by Édouard Riou from the 1867 (seventh) edition of Journey. This doubling is discussed somewhat further below (in the section “‘Scientific’ Epiphany and an Un-epic Epistemology”).

Figure 3-1 Axel and Lidenbrock flee from the sight of the shepherd and his herd of mastodons: “Immanis pecoris custos, immanior ipse!” Édouard Riou, public domain.

In the meantime, we may focus first on the scene’s classical reception. The Latin means “A tremendous herd’s guardian, more tremendous himself! Yes, more tremendous himself!” By this point in the novel, we are not surprised to see Axel turn to Virgil for an expression of emotion. But if we are right to consider Verne’s quotations of Virgil in their original contexts, and therefore to ask what effect if any is had on the novel, in this case, too, it matters that the quotation is not direct. The original is slightly different: formosi pecoris custos, formosior ipse, such that flock and guardian are originally “shapely” (or “well-kempt,” since the context is animal husbandry) rather than “tremendous.” Axel’s expression may therefore gain some of its force from an implicit difference from that ancient precedent: if we recall formosior, we may be more prepared to be struck by immanior and so feel greater sympathy with Axel’s own stricken speech.42 In a further complication to the quotation’s literary history, this difference from Virgil is not Verne’s: Verne borrowed the line, already so changed, from Victor Hugo’s The Hunchback of Notre-Dame.43 In this way Virgil had already been refurbished for modern use.

As with facilis descensus Averno, so here does the quotation’s original context complicate matters further. Unlike the first two quotations, both from the epic Aeneid, this one comes from Virgil’s earliest collection of poems, the pastoral Eclogues (ca. 39 B.C.E. [Ecl.]).44 In the fifth Eclogue, Mopsus reports an epitaph demanded of shepherds for their fellow Daphnis, who has just now died (5.40–44):

|

sprinkle the ground with leaves, draw shadows over the fountains, |

40 |

|

|

shepherds (the command that such things be done is Daphnis’ himself), and make a funeral mound, and over the funeral mound add this poem: “I, Daphnis, was—in these woods, from here to the stars—well-known, a shapely flock’s guardian, shapelier on my own.”45 |

||

Since this lies behind Journey’s climactic classical reception, some discussion of the original context is in order. Briefly, Eclogue 5 focuses on the interaction of mortal and immortal[izing] forces at a moment, and therefore on the relationship between poetry and time or eternity. This in turn suggests an interest in the relationship between lived experience and the larger forces that affect human life. The poem thus develops an image of responses to death that are reassuring in their conventionality or in their symbolic correspondence to nature, the natural world, as such. To take the concluding example, the shepherds are asked to construct a monument whose commemorative power derives in part from its raw materials’ being natural, insofar as they are both constants of (pastoral) experience and themselves changing or fleeting: leaves, water, and shade.46 Although the poem demanded of the shepherds is expressly intended to be written atop the burial mound, the interconnections among the lines suggest a close relationship between epitaph and falling leaves or rushing water, both of which were traditional symbols for change. All is thus strongly suggestive of passing time. We may imagine the leaves decaying, the water continually passing and so washing them away, and the mound itself succumbing to erosion by the water and weather.47 In these ways the commemorative monument becomes less memorable; it thus serves, not only to recall a past person, but also, perhaps more powerfully, to symbolize his passing moment or era.

All of this is in implicit contrast to the ideal endurance or desired immortality of the song, which takes on two forms: the epitaph in the meter of epic, dactylic hexameter, which seems intended to preserve memory forever, as are the epics; and the Eclogue itself, which as poetry may last in ways that leaves, streams, and a mound of earth may not. The feeling of distance, of desire unfulfilled, is intensified by the fact that Virgil’s lines are modeled on a similar speech put into the mouth of the bucolic character Thyrsis by the Greek poet Theocritus (Idyll 1, esp. 119ff.; ca. third century B.C.E.). In this context, Virgil’s self-conscious allusion draws attention to the historical contingence, the accident, of any such literary relationship. As a rewriting, the Eclogue thus expresses the same elegiac feeling about passing time as in its image of death and evanescent memorial.48 Concretely, Daphnis—as Mopsus suggests—represents a time before agricultural labor: the “Golden” or Saturnian Age, when the earth gave freely of her bounty. Likewise, Daphnis’ death symbolizes the transition to the harder “Iron” or Jovian Age in which we toil still and which presented Virgil’s idealized shepherds with actual difficulties.

Verne’s quotation of Virgil thus evokes an exemplary shepherd whose death serves to symbolize the passing of an age. Verne’s own monstrous shepherd, as well as the world he represents, may likewise be understood as limited in time; in the metafiction of the novel, that world is in fact present to us only within the frame of the narrator’s recollection. But whereas the Eclogues mourns the past age by mourning Daphnis, Journey seems to approach the past neutrally or even comically: awe at discovery, including the shock of recognition, gives way in the end to relieved laughter. In part this difference in tone may be attributed to differences between the narrators. Virgil’s Mopsus is a shepherd himself, and so identifies in a way with Daphnis: Daphnis’s death prefigures the end of Mopsus’ similar way of life. When Mopsus sings of Daphnis’ death to help himself and his interlocutor Menalcas pass the time, it is partly in response to how a time—an era—seems to be passing despite them. The entirety of Daphnis’ story thus echoes back, in anticipation, the shepherd-poets’ own mortality; nor may they expect lasting commemoration, their compliments on each other’s performance notwithstanding. This is complicated further by Menalcas’ response to Mopsus, which develops the theme of Daphnis’ death by focusing on his afterlife: we may follow Daphnis as he “wonders at the threshold of unfamiliar Olympus, / and sees the clouds and stars beneath his feet” (insuetum miratur limen Olympi / sub pedibusque videt nubes et sidera; Ecl. 5.56–57). The extraordinary continuity of Daphnis’ story, his “life” of sorts after death, serves to emphasize, in its explicit status as a fiction, the discontinuity of ordinary life. From this perspective, life is in fact severely time-limited, so the knowledge of the world one may gain in life seems limited as well.49

In sharp contrast to the worlds depicted by Virgil, lives in Verne’s fiction would seem to be in no such danger. As noted, by the end of the novel, again, his voyagers are safely back amidst the bourgeois comforts of home. But in light of Verne’s engagement with Virgil and the classical tradition, there may be a different kind of danger faced during the journey itself. In the passage surrounding Verne’s third quotation from Virgil (immanis pecoris custos. . .), Axel sees two things that cause him to exclaim in astonishment and fear. First is a “herd” of woolly mammoths, otherwise extinct, each the imposing height of a tree.50 Second is the herd’s “more tremendous guardian,” a towering super-primitive man. In his size and “impossibility”—his survival is, if anything, unlikelier than the mastodons’—he is immediately suggestive of how material discovery may outstrip human comprehension. In other words, then, any danger facing Verne’s heroes would have to do with the limits of knowledge: it is epistemological.51 To reiterate the general situation, “human knowledge” was formerly classical but must now be scientific; as both result and prerequisite, the classics are redefined as mere “tradition.”

In particular here, as Verne’s “underworld” replaces Virgil’s, the guardian serves to represent the limits of traditional, “spiritual” or supernatural understandings when confronted with merely “material” nature that is unexpectedly rich and strange. The guardian is astonishing in his materiality, his physical reality, in a way that emphasizes just how Verne’s underworld is unlike those found in ancient authors: pointedly, it lacks shades, the bodiless ghosts that confronted ancient epic heroes; this is emphasized by how it also lacks simple shadows, as discussed below. In place of those immaterial spirits, Verne’s underworld is flush with grosser matter. This includes not only the mastodons and their massive guardian, but also stupendous mushrooms, sea-monsters or living dinosaurs, and finally a human skeleton (Journey ch. 38). That last find serves to symbolize how, in this material underworld, death is not metaphorical, as if serving mainly to illuminate human life in mirror-image, but literal and physical—its actual end.

All of this is profoundly defamiliarizing: for such a guardian to be living is astonishing indeed. In Journey that fact is not cause for an ironic poetic lament as in Eclogue 5, much less for the sort of knowledge about the future that comes to the epic hero in Aeneid Book 6. Instead, the encounter causes dismay: it is precisely uncanny, as the scientist wonders whether to believe his own senses. Importantly, however, that feeling passes: although Axel expects his report to be met with readers’ skepticism, the fact of the novel makes it clear that he has recovered his certainty. In contrast, at the same time the classical tradition is made to show its limits. Whereas Virgil suffices for Axel’s emotional expression at the moment, any explanation of the guardian, as of everything else in this strange material world, must now be discovered and presented by new, modern means.

The possibility of such explanation is complicated here by how Axel’s encounter with the guardian is a kind of self-discovery: although he may wish to reject any similarity between himself and the guardian, the latter is of course somehow “human.” Axel and the guardian are thus mutually constitutive, doubling each other asymmetrically. In the context of Journey’s deep engagement with Virgil, if Axel is a sort of inverted Aeneas (the narration requires that, unlike Aeneas, he has already returned home to safety and love), then the guardian at this moment replaces the ghost of Aeneas’ father, Anchises. Whereas Anchises was emphatically immaterial (Aeneas tried and failed to embrace him three times; Aen. 6.700–702, lines that are identical to 2.792–794, where the immaterial being is Aeneas’s dead wife, Creusa), the guardian is astonishingly physical and real. Moreover, although the guardian is, in a way like Anchises, an “old man” of sorts—he is compared to Proteus, the “old man of the sea” who prophesizes when captured, while the shade of Anchises relates the future—this similarity is superficial, and he can be assumed to offer nothing like Proteus’ or Anchises’ knowledge of the future.52

As a remnant of the past, an offshoot of human prehistory, the guardian has no connection to history as such, much less to what Verne’s modern science might imagine as its rational continuation. Evoking and distorting Daphnis from the quoted Eclogue, and displacing Aeneas’ father Anchises from the Aeneid, the guardian is Journey’s most vivid representation of how classical “traditions” must now yield to “knowledge” as such.53 The guardian thus serves as a powerful symbol, not of physical danger, but of how a new materialism comes with changed epistemological possibilities and limits. In his very monstrosity and silence, he embodies a kind of the “sublime,” for which a classical tradition including Virgil’s poetry may provide analogies, but one that only a modern scientific practice can explain.

At this moment, the modern scientist is, of course, Axel, observing from an actual and notional distance. He sees the giant “at a quarter of a mile away, leaning against the trunk of an enormous kauri pine.” The forest is “[b]athed in waves of electric light.” This light, associated with the modern technology par excellence, electricity, dispels all shadows: “By a phenomenon I cannot explain, the light was uniformly diffused, so that it lit up all the sides of objects equally. It no longer came from any definite point in space, and consequently there was not the slightest shadow.”54 Although this underground forest may call to mind the ancient epic image of the dead gathering on the near bank of the river Styx, thick as autumn leaves, the absence of shadows is also of a piece with the absence, in this material world, of spiritual beings including “shades.”55 The fact that the tree is pine, with its everlasting green, may strengthen this reading, for its lack of any leaves to fall precisely rewrites those earlier epics so as to exclude even symbols of migratory souls: there is no autumn here. At the same time, the “kauri” pine in particular implies a certain kind of survival: this is a type of pine that was widespread during the Jurassic period and so betokens the material survival of a past that is so prehistorical as to be, by definition, pre-classical. In this way, any classics are present only in recollection or feeling, not in material fact: in Virgil’s underworld as rewritten by Verne, the classics are no longer, quite, real.

In this chapter, I have tried to show how Jules Verne’s Journey to the Center of the Earth engages with Virgil quite complexly, both respecting and replacing him. Ultimately Virgil is surpassed, as pieces of his influential works are, as it were, left behind in the underworld, even buried. Quotations from Virgil stud the enlarged—if rapidly contracting—“scientific” earth like precious stones: they are beautiful and expressive, even “romantic,” but are not intrinsically more interesting or meaningful, to mineralogists like Axel and his uncle, than other “minerals,” the various material and real, physical objects and phenomena that surround them. Virgil himself has become a sort of “primitive” in comparison to Verne’s modern science-heroes . . . and yet, if he has therefore become somehow “unacceptable,” to borrow from Susan Sontag, he “cannot be discarded” (1966: 6). At the time of Verne’s writing and revision of Journey (1863–1867), Virgil’s identification by T. S. Eliot as “the classic of all Europe” (1945: 31) may have been a distant eighty years in the future but it was not therefore less certain. For there is hardly an underworld in the last two thousand years of Western literary tradition that does not look back to Virgil, seeing, as did Dante’s pilgrim, that he is—as Anchises and Creusa were for Aeneas, or as Eurydice for Orpheus—already “immaterial,” already gone.

Verne’s engagement with Virgil in Journey thus reveals much about the peculiar status accorded to the ancient classic in more recent Western literary culture, especially in context of emergent and ongoing master narratives of modern science. Read with special attention to its classical receptions, Journey exemplifies a modern kind of scientific-romantic “epic,” in which the hero’s hard-won knowledge is about the distant past and the present rather than the future. Where do ancient classics fit into this experience? The novel suggests how “knowledge” is limited with regard to the hero’s affective experience, his inner life and his emotions. Somewhat paradoxically, personal, emotional experience in the present, as well as hopes for the future, would seem best expressed in the language of the past—pre-scientific or even non-scientific and therefore poetic or romantic. This might be related to Verne’s feeling that, as the modern, material world is more thoroughly explored—as each unknown area becomes known—the only “place” truly open for exploration is the past. For the romantic feeling that accompanies and inspires exploration, the more distant the past, the better. This may mean that a new, materialist definition of “knowledge” excludes the classics entirely, classifying them as mere “tradition.”

In an important article, “Literary Intertexts in Jules Verne’s Voyages Extraordinaires,” Arthur B. Evans, having surveyed Verne’s extremely wide range of quotations from and allusions to other authors, writes that, while “a limited number of these intertextual phenomena have been identified and discussed in the critical scholarship . . . most have yet to be fully explored, and the potential for detailed comparative exegesis remains very rich indeed.”56 Evans refers here in particular to Verne’s frequent and meaningful engagement with Edgar Allen Poe, but his point may be taken more generally. In this chapter I have sought to show one way in which that “rich potential” may be actualized: by studying Verne, exponent of modern SF, in relation to the classics and the classical tradition. I have not attempted to offer a complete account of Journey’s reception even of Virgil, much less to explore at any depth the novel’s other classical references. Together with post-classical material, these form the strata of Verne’s geologically learned writing and “volcanic” feeling.57 And of course no single modern work, even one as influential in the SF tradition as Journey, may on its own justify the claim that there is a fundamental difference in epistemology between ancient literature and modern SF.

But I do hope to have shown that the argument is plausible. In particular I hope it has been clear that the journey undertaken by Verne’s science-heroes, inspired in the narrative by Arne Saknussem, in literary-historical terms is modeled on, and modifies, an ancient epic-heroic journey under the earth as depicted, vividly and influentially, by Virgil. Perhaps the most crucial and consequential difference between Verne’s modern, “romantic” novel and Virgil’s ancient epic is the novel’s insistence on the materiality of the world below, as against the epic’s tradition of an underworld that is rather more spiritual or metaphysical. In Virgil, as in much of the tradition after him, it is the hero himself who is thus strangely material in a world otherwise inhabited, if that is the word, by insubstantial shades.58 In contrast, in Journey the salient difference between the explorers and the living inhabitant of the world within the earth is not material or metaphysical, for they are all of them similarly material and real. Instead, the deepest difference is epistemological: the voyagers observe him, they are able to categorize him, they can “understand him,” while he does not seem to notice them and, unlike the shades encountered by the ancient epic hero, can offer no knowledge of the historical past, much less prophesy the future. That monstrous guardian may well be compared to figures from classical mythology but he stands for a time that is far more ancient still, glimpses of which are made possible by sciences, like geology, unanticipated in antiquity. In the light—or in the shadow?—cast by such a figure, a figure of the modern scientific imagination, ancient classics can become something like “mere tradition.” Read in this way, Journey stands as one example of how modern SF remains profoundly fascinated with, and yet also profoundly challenges, the classical tradition.

I hope that this list will help make possible further study of Journey’s, and Verne’s, classical receptions. As throughout this chapter, here the French is drawn from the 1867 edition, translations from the French are drawn from Butcher (2008) (with page numbers), and translations from the Latin are my own (see note 4).

Journey ch. 1: “Il était professeur au Johannaeum.” Butcher (2008: 219): “a famous classical grammar school”

Journey ch. 4: “ce travail logogryphique, qu’on eût vainement proposé au vieil Oedipe!” Butcher (2008: 18): “that word-puzzle . . . solved”: Oedipus and the Sphinx.

Journey ch. 4: “Enfin, dans le corps du document, et à la troisième ligne, je remarquai aussi les mots latins ‘rota,’ ‘mutabile,’ ‘ira,’ ‘nec,’ ‘atra.’ ‘Diable, pensai-je, ces derniers mots sembleraient donner raison à mon oncle sur la langue du document! Et même, à la quatrième ligne, j’aperçois encore le mot ‘luco’ qui se traduit par ‘bois sacré.’ Il est vrai qu’à la troisième ligne, on lit le mot ‘tabiled’ de tournure parfaitement hébraïque, et à la dernière les vocables ‘mer,’ ‘arc,’ ‘mère,’ qui sont purement français. . . . Quel rapport pouvait-il exister entre les mots ‘glace, monsieur, colère, cruel, bois sacré, changeant, mère, arc ou mer’?” Butcher (2008: 19): “I spotted the Latin words rota, mutabile, ira, nec, and atra. . . . ‘These last few words seem to confirm my uncle’s view about the language in the document! In the fourth line I can even see luco, which means “sacred wood.” It’s true that the third line also includes tabiled, that sounds completely Hebrew to me, and the last one, mer, arc, and mère, pure and unadulterated French.’” “What possible connection could there be between ice, sir, anger, cruel, sacred wood, changeable, mother, bow, and sea?”

Journey ch. 4: “des mots latins, entre autres ‘craterem’ et ‘terrestre’!” Butcher (2008: 20): “Latin words like craterem and terrestre!”

Journey ch. 5: “Ce qui, de ce mauvais latin, peut être traduit ainsi: Descends dans le cratère du Yocul de Sneffels que l’ombre du Scartaris vient caresser avant les calendes de Juillet, voyageur audacieux, et tu parviendras au centre de la Terre. Ce que j’ai fait. Arne Saknussemm.” Butcher (2008: 25): ““In Snaefells Yoculis craterem kem delibat umbra Scartaris Julii intra calendas descende, audas viator, et terrestre centrum attinges. Kod feci. Arne Saknussemm.” Which, when translated from the dog-Latin, reads as follows: Go down into the crater of Snaefells Yocul which the shadow of Scartaris caresses before the calends of July, O audacious traveller, and you will reach the center of the Earth. I did it. Arne Saknussemm.”

Journey ch. 16: Pluto. Butcher (2008: 83).

Journey ch. 30: Proserpina. Butcher (2008: 139).

Journey ch. 37: Wild Ajax. Butcher (2008: 175).

Journey ch. 38: Orestes’ body, Pausanias, Polyphemus (giants), Cimbrians. Butcher (2008: 181).

1 An early version of this material was presented at the 2010 Annual Meeting of the Classical Association of the Atlantic States. It could not have reached its present form without the assistance of various readers, including the Press’s anonymous reviewers and the team acknowledged in this volume’s introduction. Special thanks are owed to my father for weekly visits to comicbook shops; à ma mère d’avoir étudié le français lorsque j’étais enfant; and to Brett M. Rogers, co-editor, colleague, and indefatigable friend on many fantastic journeys.

2 Cf. publisher J.-G. Hetzel’s description of the project of Verne’s Extraordinary Journeys: to “outline all the geographical, geological, physical, and astronomical knowledge amassed by modern science and to recount, in an entertaining and picturesque format . . . the history of the universe” (in the prologue to Verne [1866]); on this project, see further Evans (1988: 7–31). Work of such scope admits contradictory readings: e.g., Verne’s writing has been said to emerge directly from bourgeois ideology as it pertains to science (Barthes 1957) but also to articulate fractures in that ideology (Butour 1949, Macherey 1966). Some other interpretations of Journey are noted below. Raymond and Compère (1976) is a useful introduction to Verne studies, while Compère (1977) is good on Journey. A special issue of Science Fiction Studies (32.1 [2005]) is devoted to essays on Verne’s work. On the man himself, see Butcher (2006).

3 Ancient epic heroes like Aeneas are set in motion against their wishes, struggling to get home or, as in Aeneas’ case, to reach a new place that must substitute for a home that has been lost. By contrast, modern heroes like Verne’s leave home in order to explore unknown places and then return, finding that little if anything has changed; on Verne’s circular cartographies, see Harpold (2005), generally Butcher (1991, paying special attention to Journey on 60–74), and Martin (1985: 144–150). Such modern travelers may have more in common with ancient explorers like the Greek historian Herodotus (fifth century B.C.E.), possessed of a certain rationalizing impulse, than with heroes like Aeneas, driven by powers beyond their comprehension and control. On “epiphanies” ancient and modern, see Grobéty (this volume, chapter twelve).

4 Uniquely among his novels, Journey was revised by Verne between editions. In this chapter I use the shorthand Journey to refer to the 1867 edition—the seventh—which includes the climactic encounter in the “underworld” (chs. 37–39) discussed below (in the sections “‘Scientific’ Epiphany and ‘Romantic’ Elegy” and “‘Scientific’ Epiphany and an Un-epic Epistemology”). For the reader’s convenience, all translations of Verne into English are from Butcher (2008), with some modifications. All translations from Latin are my own.

5 Butcher (2008: 60). Journey ch. 11: “M. Fridriksson me lança avec son dernier adieu ce vers que Virgile semblait avoir fait pour nous, voyageurs incertains de la route.” “Voyagers uncertain of the way” is my replacement for Butcher’s “uncertain travellers on the road”: the phrase should capture the connection between Axel’s uncertainty and his feeling that the quotation from Virgil is therefore perfectly apt. This should also make it clear to readers without French that “voyageurs” is, of course, an echo of the novel’s title.

6 Butcher (2008: 60). On Lidenbrock’s mastery of many languages, see note 20.

7 Immediately preceding quotations from Verne in English are from Butcher (2008: 48). Journey ch. 9: “Mais un charmant homme, et dont le concours nous devint fort précieux, ce fut M. Fridriksson, professeur de sciences naturelles à l’école de Reyjkjawik. Ce savant modeste ne parlait que l’islandais et le latin; il vint m’offrir ses services dans la langue d’Horace, et je sentis que nous étions faits pour nous comprendre. Ce fut, en effet, le seul personnage avec lequel je pus m’entretenire pendant mon séjour en Islande.”

8 Cf. Evans (1988: 33–102) on how the “Ideological Subtexts in the Voyages Extraordinaires” comprise a “positivist perspective” (37–57) and a “romantic vision” (58–102).

9 Butcher (2008: 4). Journey ch. 1: “Or, il y a en minéralogie bien des dénominations semi-grecques, semi-latines, difficiles à prononcer, de ces rudes appellations qui écorcheraient les lèvres d’un poète. Je ne veux pas dire du mal de cette science. Loin de moi. Mais lorsqu’on se trouve en présence des cristallisations rhomboédriques, des résines rétinashpaltes, des ghélénites, des fangasites, des molybdates de plomb, de tungstates de manganèse et des tianiates de zircone, il est permis à la langue la plus adroite de fourcher.”

10 This “pronunciation problem” appears later, when Lidenbrock, while giving an extemporaneous “lecture” on the human skeleton they have discovered underground, stumbles over the title “Gigantosteology” (ch. 38; Gigantosteology is an actual work, Habicot [1613]).

11 Cf. the complaint voiced by the classicist A. E. Housman as depicted in Tom Stoppard’s The Invention of Love: “Homosexuals? Who is responsible for this barbarity? . . . It’s half Greek and half Latin!” (1997: 91).

12 Verne seems to have borrowed the idea of such a cryptogram from Poe’s “The Gold Bug” (1843); Verne analyzed Poe, including that short story, in “Edgar Poe et ses oeuvres” (1864b). It may be that the cryptogram marks its knowledge as forbidden: Butcher notes (2008: 221 n. 13) that “Galileo’s letter of 30 July 1610 used an anagram to hide the revelation that Saturn’s ring was composed of two satellites.”

13 Butcher reports (2008: xxxii) that in a recently discovered manuscript of Journey, made known to scholarship only recently, and as of this writing not completely available, “a large number of details in the cryptic message are not the same” as in the published novel; he does not say which, but presumably would have mentioned if, as seems unlikely, the language were not Latin. Sturluson’s Heims-Kringla, or “The History of the Kings of Norway,” is of course an additional indication of Journey’s engagement with Icelandic themes.

14 Butcher (2008: 13–14). Journey ch. 3: “Ce Saknussemm . . . était un homme instruit; or, dès qu’il n’écrivait pas dans sa langue maternelle, il devait choisir de préférence la langue courante entre les esprits cultivés du XVIe siècle, je veux dire le latin. Si je me trompe, je pourrai essayer de l’espagnol, du français, de l’italien, du grec, de l’hebreu. Mais les savants du XVIe siècle écrivaient généralement en latin. J’ai donc le droit de dire a priori: ceci est du latin.” Saknussemm is “loosely based on Professor Árni Magnússon (1663–1730), an Icelandic scholar . . . who always wrote in Latin” (2008: 221 n. 13).

15 On Latin as a language of international communication, especially among scholars, see, e.g., Waquet and Howe (2001); Farrell (2001).

16 Butcher (2008: 14). Journey ch. 3: “Mes souvenirs de latiniste se révoltaient contre la prétention que cette suite de mots baroques pût appartenir à la douce langue de Virgile.” The phrase “soft tongue of Virgil” may recall Byron’s Beppo, stanza 44: “I love the language, that soft bastard Latin, / Which melts like kisses from a female mouth. . . .” Although by “bastard Latin” Byron means Italian, the poem nonetheless seems to evoke something like Axel’s feelings about Latin. Byron’s sensuality seems to go farther than Verne’s, but Verne himself may be read as having a “volcanic” sensuality; for the term, Butcher (2008: xx), and for some thoughts on symbolized sexuality, idem (2008: xxv–xxvi).

17 Butcher (2008: 15). Journey ch. 3: “je l’adorer, si toutefois ce verbe existe dans la langue tudesque!”

18 Butcher (2008: 15 and 16). Journey ch. 3: “Je t’aime bien, ma petite Graüben!” and “Oui, sans m’en douter, en amoureux maladroit, j’avais tracé cette phrase compromettante!” In the manuscript referred to above, note 13, Axel’s feeling for Graüben is evidently given additional emphasis; see Butcher (2008: xxxii).

19 Whether this is complicated by Verne’s Catholicism is beyond the scope of this chapter.

20 Butcher (2008: 17). Journey ch. 3: “j’attendais donc que le professeur laissât se dérouler pompeusement entre ses lèvres une phrase d’une magnifique latinité.” Parenthetical quotation, ch. 1: “mon oncle, je ne saurais trop le dire, était un véritable savant.” Lidenbrock is described by Axel as “a genuine polyglot: not that he spoke fluently the 2,000 languages and 4,000 dialects employed on the surface of the globe, but he did know his fair share” (Butcher 2008: 10). Journey ch. 2: “Lidenbrock . . . passait pour être un véritable polyglotte. Non pas qu’il parlât couramment les deux mille langues et les quatre mille idiomes employés à la surface du globe, mais enfin il en savait sa bonne part.” In context of a journey “to the center of the earth,” the phrase “on the surface of the globe” could foreshadow certain confusion in the world below.

21 Translating Virgil’s Averno as “Underworld” depends on a sort of metonym, since Avernus is not the Underworld as such but an entrance into it. As Butcher puts it (2008: 224 n. 92), Avernus is “a lake in a crater near Naples, believed to be the source of the river Styx.” Translating it as “Underworld” also unfortunately obliterates a wordplay that was of evident interest to Verne and that, in a plot set in motion by a cryptogram, should interest us: that linking the name of the entrance, “aVERNus,” and the name of the author, “VERNe.” Butcher suggests (2008: xxvii) that “[t]he novel is generated by the personal anagram, not once but repeatedly,” pointing to crucial terms like “à l’ENVERs” (“backwards”), “RENVErsé” (“reversed”), “caVERNE” (“cavern”), “gouVERNail” (“helm”), and “ViRlaNdaisE” (Graüben’s toponym). Going further, “the word Averni . . . may indicate a source of inspiration in medieval ideas of an underground Hell” (Butcher 2008: xvii). Verne thus draws on Virgil complexly, both directly and via intermediaries (e.g., Dante). Certain significant departures from Virgil’s underworld are discussed below. Virgil himself of course draws on and deviates from earlier authors, including Homer (Odyssey Book 11 [Od.]).

22 Butcher (2008: 92). Journey ch. 18: “nous nous laissions aller sans fatigue sur des pentes inclinées. C’était le facilis descensus Averni de Virgile.”

23 Cf. Aeneas’ “amazement” (root mir-) at aspects of the Underworld: the souls gathering on the near side of the river Styx (Aen. 6.317), the Elysian Fields (6.651), and Anchises’ naming of Romans-to-be, leading to his famous injunction to “spare the defeated and battle down the proud in war” (parcere subiectis et debellare superbos; 6.853; at 6.854 the Sibyl shares Aeneas’ amazement). Aeneas’ experience, like Axel’s in this passage and elsewhere, is intensely visual; verbs for “seeing” occur frequently in Aeneid Book 6, and already in Book 2 the veil has been stripped from Aeneas’ eyes by Venus (2.604ff.).

24 Butcher (2008: 92). Journey ch. 18: “La lave, poreuse en de certains endroits, présentait de petites ampoules arrondies: des cristaux de quartz opaque, ornés de limpides gouttes de verre et suspendus à la voûte comme des lustres, semblaient s’allumer à notre passage. On eût dit que les génies du gouffre illuminaient leur palais pour recevoir les hôtes de la terre.” This may recall Psyche’s first sight of the palace of Cupid as described by Apuleius (Metamorphoses 5.1).

25 For introductions to scholarship on the Aeneid, see, e.g., Kennedy (1997) and the chapters in Farrell and Putnam (2010), esp. chapters 1–7. Several recent translations have included thought-provoking introductions: see esp. Bernard Knox’s introduction to Robert Fagles’s translation (1998) and Elaine Fantham’s introduction to Frederik Ahl’s translation (2007).

26 Facilis descensus Averno: / noctes atque dies patet atri ianua Ditis; / sed revocare gradum superasque evadere auras, / hoc opus, hic labor est. pauci, quos aequus amavit / Iuppiter aut ardens evexit ad aethera virtus, / dis geniti potuere.

27 In this chapter I do not adopt a particular theory of reception; see, e.g., Hardwick and Stray (2008), Martindale and Thomas (2006), and Hardwick (2003). On the value of considering the fullest available “backstory” to a quotation or allusion, granting that the full story might not have been “live” in the minds of all intended readers, see, e.g., Mastronarde (2002: 44–45).

28 Aen. 6.893–898: Sunt geminae Somni portae, quarum altera fertur / cornea, qua veris facilis datur exitus umbris, / altera candenti perfecta nitens elephanto, / sed falsa ad caelum mittunt insomnia Manes. / his ibi tum natum Anchises unaque Sibyllam / prosequitur dictis portaque emittit eburna. These lines are modeled on Homer Od. 19.562–557.

29 Strictly speaking, Aeneas “follows a path to the ships and sees his companions again” (ille viam secat ad navis sociosque revisit; Aen. 6.900). In choice of verb (revisere), Virgil may subtly emphasize how remarkable it is for anyone to escape the underworld and “see again”—that is, to return to “life,” which is conventionally equated, in ancient literature, with “light.”

30 The question has excited scholarship; for some general remarks see Austin (1986: 274–278) and West (1990).

31 Aeneas’ unshadelike physicality is emphasized, e.g., when he boards Charon’s ferry to cross the river Styx, and the weight of his living body causes the ferry to take on water (Aen. 6.413–414). In Journey (ch. 39), Verne’s heroes cast no shadows: although this may recall Dante’s shades, which likewise do not cast shadows (unlike the pilgrim Dante, who does), it is given a pseudoscientific explanation that further distinguishes Journey’s world from that of the epic; see below.

32 This view is discussed and dismissed by Austin (1986: 276).

34 Arguably, this crucial component of Aeneas’ character precedes his experience in the Underworld: he has already had to leave behind his wife, Creusa, in the conflagration of his home city of Troy (Aen. 2.768–794). That loss may be marked as especially isolating; Aeneas has been faced with her shade in the world above but does not encounter her in the Underworld. By contrast, Dido, whom Aeneas does encounter in the Underworld, is paired there with her loving spouse, Sychaeus. Cf. Satan’s famous self-description in Milton, in terms that recall Aeneas’ harassment by divine anger and his inability to escape himself: “Which way shall I fly / Infinite wrath and infinite despair? / Which way I fly is Hell; myself am Hell” (Paradise Lost 4.73–75).

35 Cf. the younger Pliny’s description of the eruption of Vesuvius in 70 C.E. (Epistulae 6.16).

36 That closure is one example of Verne’s preference for circularity; see above, note 3. A similar inversion, with its own evocation of an earlier underworld, may be detected in Axel’s having seen, through “the 3,000-foot long tube” formed by the chimney of the initial descent, “a brilliant object”: a star that Axel identifies as “Beta of the Little Bear” (Butcher 2008: 89–90); Journey ch. 17: “j’aperçus un point brillant à l’extrémité de ce tube long de trois mille pieds, qui se transformait en une gigantesque lunette. C’était une étoile dépouillée de toute scintillation, et qui, d’après mes calculs, devait être B de la Petite Ourse”). When the time comes to descend further, Axel similarly “raised [his] head and looked through the long tube at the sky of Iceland, ‘that I would never see again’” (Butcher 2008: 92); Journey ch. 18: “je relevai la tête, et j’aperçus une dernière fois, par le champ de l’immense tube, ce ciel de l’Islande ‘que je ne devais plus revoir’.” I have not discovered why the phrase “that I would never see again” is marked as a quotation; it is repeated in Verne’s later The Floating Island (1871), but I do not know an earlier appearance. These two moments together may recall the end of Dante’s Inferno, when the pilgrim Dante and Virgil, having traveled together through Hell, see at last the open sky and the stars (34.139). When Verne’s travelers emerge, it is daytime, and the sun, evocatively called “the radiant star” (“l’astre radieux”), is “pouring on to [them] waves of splendid irradiation” (Butcher 2008: 210; Journey ch. 44: “nous versait à flots une splendide irradiation”). There is much to be said about how Verne’s “underworld” draws on Dante’s in its own right and as it transmutes Virgil’s. Here I can only note that, in a profound and mysterious way, when European literature, especially after Dante, goes into the earth, it seems to go there with Virgil; see, e.g., Hardie (1993: 57–87) and generally the chapters in Farrell and Putnam (2010), esp. Jacoff (2010). For discussion of Virgil’s more general influence on premodern authors including Dante, see Ziolkowski and Putnam (2008). As far as SF and the linked genre of fantasy go, perhaps the most important modern example of underworlds being Virgilian is provided by J. R. R. Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings (1954–1955); see, e.g., Obertino (1993) and Simonis (2014). I intend to explore classical receptions in Tolkien’s underworlds further in future work. One rich contemporary example, among many others, is provided by A. S. Byatt’s The Children’s Book (2011), which makes powerful use of Virgil’s facilis descensus (e.g., 250–254), via a story-within-the-story called “Tom Underground” (esp. chapters 16ff.); I have discussed Byatt in Stevens (2013), after Cox (2011: 135–152).

37 We could develop this image further by contrasting Verne’s scientific understanding of the volcano’s activity with ancient mythologies in which monsters like Typhoeus or the Cyclops, having been trapped under the earth, cause eruptions and earthquakes; thus did ancient mythology account for, e.g., Sicily’s Mount Aetna. (A connection to the Cyclops would be strengthened by how Axel’s encounter with the monstrous guardian, discussed below, echoes Odysseus’ reported encounter with the Cyclops in Od. Book 9.) Recalling such monsters only to dismiss them allows Verne to emphasize modern science over mythography. Likewise, the fact that Verne’s heroes escape on a “raft,” as if by means of a “sea” but one powered by a sort of fire, is suggestive of how the traditional domain of Vulcan has been appropriated and de-mythologized by modern technoscience. On Vulcan de-mythologized, cf. Marx’s unpublished version (from 1857) of the introduction to his “Contribution to the Critique of Political Economy” (1859), quoted above, in the introduction to this volume. Cf. Milton’s famous “correction” of Vulcan’s fall as described by Homer (Iliad 1.591–593 [Il.]): “Men called him Mulciber, and how he fell / From Heav’n they fabled . . . . Thus they relate, / Erring” (Paradise Lost 1.740–747); Milton’s “correction” is of course theological, not technoscientific. For additional examples of this sort of appropriation in Journey, see the chapter appendix.

38 For Virgil and Lucretius, see Braund (1997); Farrell (1997); and chs. 7, 9, and 12–19 in Gillespie and Hardie (2007). Lucretius has played an important role in “scientific” thinking in Europe; see Johnson and Wilson (2007) and Greenblatt (2011). For discussion of Lucretius in connection with SF, see Rogers and Stevens (this volume, introduction) and Weiner (this volume, chapter two).

39 Butcher (2008: 214). Journey ch. 45: “Voici la conclusion d’un récit auquel refuseront d’ajouter foi les gens les plus habitués à ne s’étonner de rien. Mais je suis cuirassé d’avance contre l’incrédulité humaine.”

40 Butcher (2008: 186). Journey ch. 39: “Je regardai, haussant les épaules, et décidé à pousser l’incrédulité jusqu’à ses dernières limites. Mais, quoque j’en eus, il fallut bien me rendre à l’évidence. En effet, à moins d’un quart de mille, appuyé au tronc d’un kauris énorme, un être humain, un Protée de ces contrées souterraines, un nouveau fils de Neptune, gardait cet innombrable troupeau de Mastodontes! Immanis pecoris custos, immanior ipse! Oui! immanor ipse!” These lines, and portions of surrounding sections (the end of chapter 37, part of 38, and all of 39), were added by Verne to Journey’s seventh edition (1867). Scholarly consensus is that the additions were made to take advantage of public interest in prehistory spurred by the recent publication of Charles Darwin’s work. This does not mean that Verne replicates Darwin: his characters seem to express instead “a divine plan progressivism” (Standish 2004: 126).

41 On doubles and the uncanny, see seminally Freud (1919), including discussion of Otto Rank’s concept of “the double,” and Jentsch (1906), with discussion of E. T. A. Hoffman’s “Der Sandmann” (1816). In Freud’s terminology, the encounter in Journey is “uncanny” (Unheimlich); see note 53. As a result, the “science” is, at least at first, called into question; cf., e.g., Harris (2000), Unwin (2000), and Martin (1985: 122–179), portions of which are quoted below, in note 51.

42 In a pun-loving author like Verne, it is possible that immanior not only means “tremendous” but also, via a pun with Latin manes, “shades,” suggests an “unshadelike” or “unghostly” aspect to the guardian. This would serve to emphasize further the difference between Virgil’s land of insubstantial, spiritual shades and Verne’s material “underworld.”

43 Notre-Dame de Paris, 1831; ch. 4, sect. 3, title.

44 For overviews of the Eclogues, see Martindale (1997) and Clausen (1995).

45 Spargite humum foliis, inducite fontibus umbras, / pastores (mandat fieri sibi talia Daphnis), / et tumulum facite, et tumulo superaddite carmen: / “Daphnis ego in silvis, hinc usque ad sidera notus, / formosi pecoris custos, formosior ipse.”

46 The presence of shadows or ghosts (both umbrae; the ambiguity in the Latin may be deliberately emphasized) is Virgil’s innovation in pastoral poetry; for some differences between Virgil’s landscape and that of his chief model, Theocritus, see Clausen (1995: xxvi–xxx).

47 In a context informed by the epic, this image recalls the famous simile—in Homer, Virgil, Dante, and others—comparing human lives or souls to autumn leaves; see also note 55. Cf. Thomas Hardy’s “few leaves lay on the starving sod; / —They had fallen from an ash, and were gray”; and his “pond edged with grayish leaves” (“Neutral Tones” 3–4 and 16). If Virgil’s flowing water is in one sense revivifying, in another it is a source of some despair, for traditionally water symbolized how human meaning cannot be made permanent: e.g., Catullus writes of how a seductive lover’s words “ought to be written on the wind and running water” (in vento et rapida scribere oportet aqua; 70.4); cf. Heraclitus’ famous dictum that one cannot step into the same river twice.

48 To refer again to Hardy, in parallel to the gray and decaying leaves, Virgil’s poem would be the “gray-brown” thrush singing its song coincidental to the poet’s mourning; although the “Darkling Thrush” is not expressly “gray-brown,” the poem bearing its name shares Virgil’s elegiac feeling. The poet also directs some of his regard to himself, resulting in a feeling similar to Coleridge’s description of the man, the “poor wretch,” who “filled all things with himself, / and made all gentle sounds tell back the tale / of his own sorrow” (“The Nightingale” 19–21).

49 A reading of the Daphnis episode as having to do in part with the limits imposed on knowledge by mortality may be strengthened by the similarity between Virgil's description of Daphnis’ projected literal or physical ascent, with the heavens “beneath his feet” (sub pedibus; Ecl. 5.57) and the more figurative or mental ascent by the man who has divined the reasons for things and can therefore position death likewise “beneath his feet” (sub pedibus; G. 2.492); see above, note 38.

50 The mastodons’ “trunks swarming about below the trees like a host of serpents” (Butcher (2008: 186); Journey ch. 39: “les trompes grouillaient sous les arbres comme une légion de serpents”) recall the dangers of the Garden of Eden, perhaps as transmuted by Milton, who imagines the fallen angels transformed into snakes (Paradise Lost 10.504ff). Verne’s engagement with Biblical literature would repay close study; see Chelebourg (1988).

51 For Verne’s interest in epistemological problems, cf. Martin (1985: 122–179), arguing that the “Voyages seek to construct an encyclopedism and an academy. . . . But the Academy and the Encyclopédie were no longer, in the age of Verne, stable institutions” (172). As a result, “[e]pistemologically, the ultimate particles of Vernian matter elude quantification and designation. Aesthetically, the realist enterprise of definitive description is indefinitely postponed” (178). Martin refers to this tendency as “anepistemophilia,” something like “love of ignorance.” Cf. Butcher’s appraisal (2008: xxvi–xxvii): “Journey cannot be excluded from the general orbit of late Romanticism. But Verne is simultaneously a Realist. . . . The paradox, though, is that so much Realism in the externals leads to the opposite of realism in the mood: Verne’s positivistic aspects culminate in the wildest longings and imaginings. . . . The Journey proves that the most down-to-earth Realism can . . . lead to the most high-blown Romanticism.”

52 For Proteus, see Homer Od. 4.412ff.; Virgil G. 4.387ff.

53 Limitations of space prevent me from discussing more fully the complex literary history of the scene’s other classical references, including to Proteus and Neptune. I regret in particular not having the space to consider how Verne’s revision of Virgil’s underworld looks back to Homer’s, in which Odysseus encounters a giant shepherd (Od. Book 11). The epistemological situation described here—a tenuous “scientification” of the uncanny encounter with the double, now material—is an important trope in modern SF; see note 41. To be traced back at least to Frankenstein (1818), this trope appears in many later works, e.g., Stephenson’s The Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde (1886), Tolkien’s The Hobbit (1937), Solaris (Andrei Tarkovsky 1972), and The Thing (John Carpenter 1982). Interestingly for the early history of modern SF, it appears in connection with Percy Shelley: his Prometheus Unbound includes an encounter with a Doppelgänger (1.191–199), while Percy himself is reported, by Mary, to have once encountered his own double (Bennett 1980: 245).

54 Butcher (2008: 184). Journey ch. 39: “Par un phénomène que je ne puis expliquer, et grâce à sa diffusion, complète alors, la lumière éclairait uniformément les diverses faces des objets. Son foyer n’existait plus en un point déterminé de l’espace et elle ne produisait aucun effet d’ombre.”

55 The image of people, especially the dead, gathering thick as falling leaves may be found in, e.g., Homer (Il. 6.146), Virgil (Aen. 6.309–310), and Milton (Paradise Lost 1.301–303). Cf. Dante’s wood of ghostly trees (Inferno 13).

56 Evans (1996: 180–181).

57 One example of Journey's classical sources aside from Virgil is Xenophon’s Anabasis; see L’Allier (2014: 286–287). For a sketch of some of Journey’s most important post-classical sources, see Butcher (2008: xvii–xx, and x). Many of these are premodern and share what may be described, in Butcher’s words, as a “medieval belief, not entirely dismissed in the nineteenth century, that the centre of the Earth could be reached via huge openings at the poles” (xix–xx); on “hollow earth” stories, see Standish (2004). Verne’s beloved Poe was a “clearing-house for many” of these ideas (Butcher 2008: 221 note 25).

58 Cf. the discussion by Weiner (this volume, chapter two) about the unprecedented corporeality of the corpse reanimated by the witch Erichtho in Lucan’s Bellum Civile.