Tensions were running high on the Hebridean island of Islay. It was the inaugural Wryter Cup match between the journalists of England and Scotland. After two days of scintillating play on the world-famous Machrie links, the scores were close, and now it was the afternoon singles that were to determine the match.

Heading the field as twenty-four golfers went out on that windy afternoon of 29 March 1998, were the two captains, George Pascoe-Watson (political editor of The Sun) for the Scots, and Webster, of The Times, for the brave English. As the skippers walked up the third fairway, my phone, carried in case the news desk needed me, rang loudly. Rather embarrassed to have disturbed George, I grabbed the phone and after a second said: ‘Oh, hi Robin.’

The conversation went on, with George regarding me with some curiosity. ‘It’s Cookie,’ I said with my hand over the mouthpiece. The foreign secretary, for it was he, had things to tell me and as a political correspondent you don’t put your phone down on such a dignitary. But we had eleven pairs of golfers following us, and in the twosome behind was a veritable celebrity, Lawrence Donegan – later to be golf correspondent of The Guardian, author of one of the finest books on golf ever written, Four Iron in the Soul, former bass player of Lloyd Cole and The Commotions, and self-confessed star of the Scottish side.

I will deal with the contents of the chat later but with the increasingly irate Donegan shouting at me from behind – accusing me of the golfing sin of slow play – I scribbled notes on a few old scorecards from my bag and, every now and then, put the still-talking foreign secretary down on the grass while I hit a smoking five-iron towards the green or sank the occasional putt.

Donegan was unaware of the subject of my call and was hardly placated later when he learnt. Some things are sacred, and the golf course is one of them. Eventually the call ended and the match proceeded. Scotland won the team competition and modesty prevents me from mentioning who took the individual prize.

The story of why Cook called me that Sunday afternoon began in the foreign secretary’s office in Whitehall the previous Thursday. I had been given an interview to mark the halfway point of Britain’s six-month presidency of the European Union. He landed me with a good story. A few months earlier – as I explain in an earlier chapter – Gordon Brown had ruled out British membership of the euro for the parliament, and the foreseeable future. The story I had written predicting the announcement had caused an almighty storm.

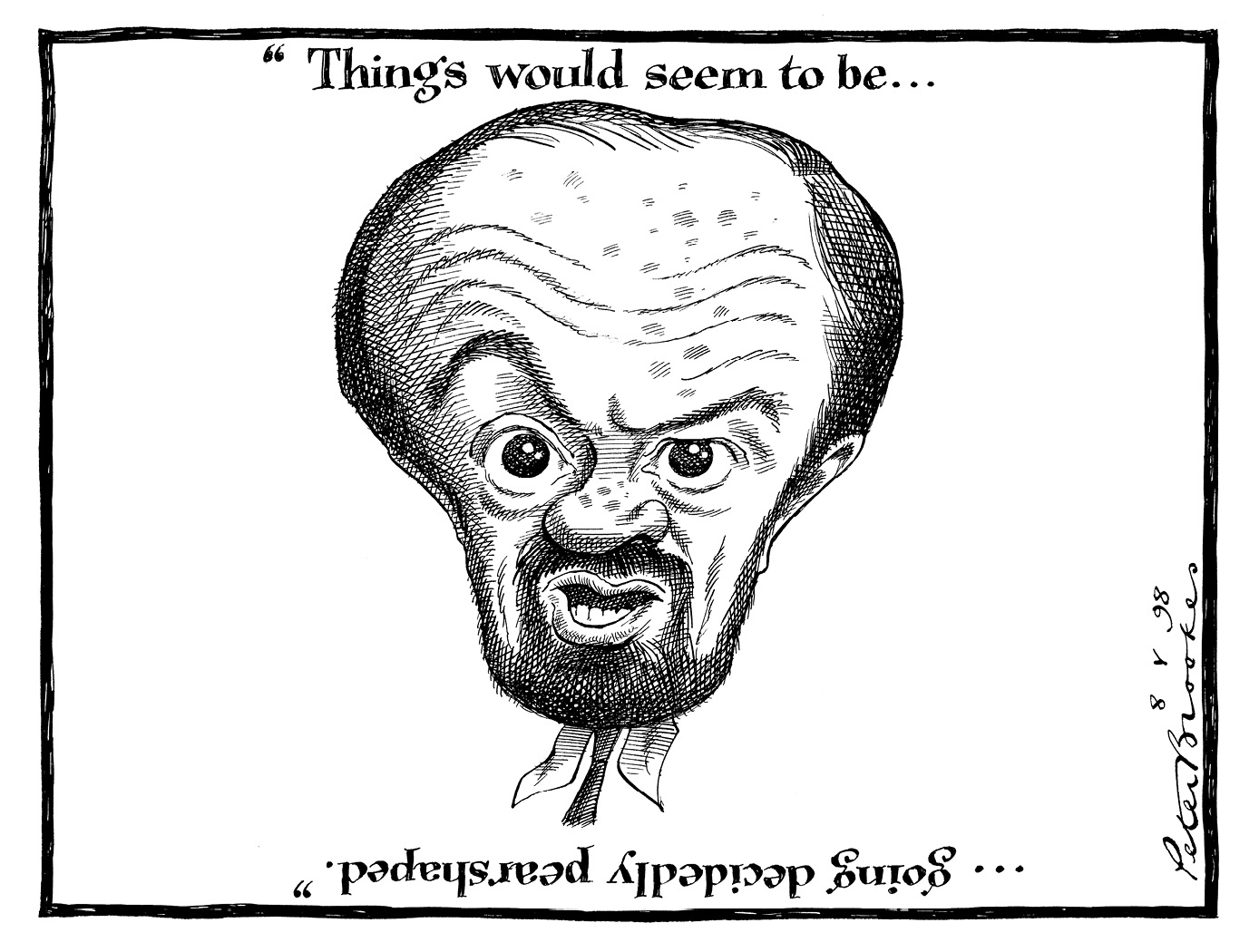

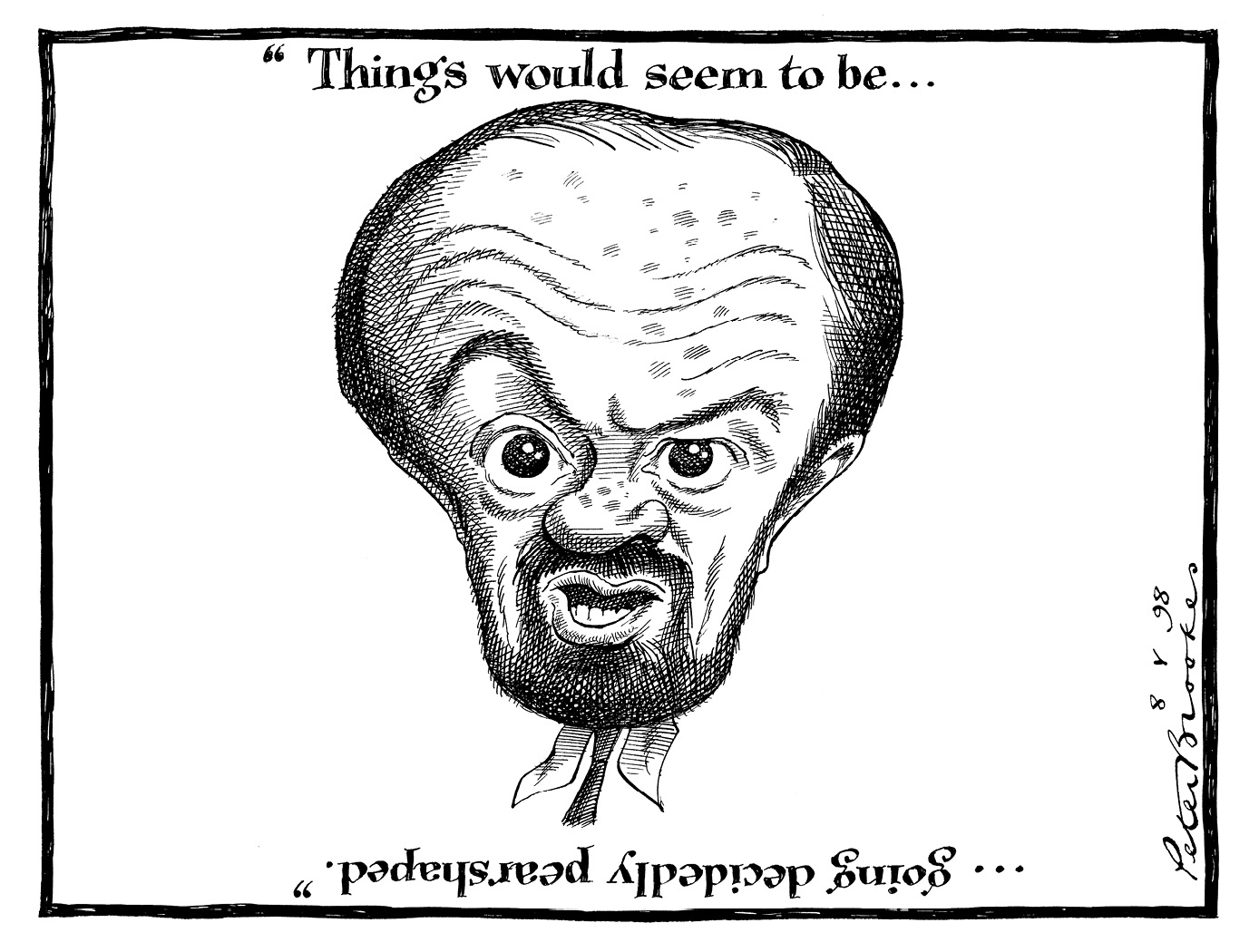

But now Cook, who always enjoyed winding Brown up, signalled that Britain could well be joining in the next parliament, saying it would be difficult and unwise to stay out if the single currency proved to be a success. In my story I described the remarks as the clearest hint that the foreign secretary would be pushing for a referendum early in the next parliament if Labour was re-elected.

Knowing that I was heading for Scotland, I could not have been happier. I had a potential splash in my pocket which I would send in on Sunday for Monday’s paper. But as the interview ended, Robin – with whom I had always had a very good working relationship – took me aside and told me he wanted to tell me something else.

The previous August he had announced that he was leaving his wife and marrying his secretary, Gaynor Regan – after being told while at Heathrow Airport by Alastair Campbell that the News of the World was about to break the story of his affair. Now Robin wanted to tell me that he and Gaynor were getting married on Sunday, 19 April and that the ceremony, away from the public eye, would be at the foreign secretary’s official country residence of Chevening in Kent.

Wow, I had two stories – one splash about the euro and a lovely personal sidebar about Cook’s wedding plans. As I boarded the plane to Glasgow, I was content. However, on the Saturday evening one of the stories fell down. I got a call at the Machrie Hotel from Peter Bean, Cook’s press man, who apologized and said that The Mail on Sunday had beaten us to it. I feared for my euro story, but no, what had happened was that Margaret Cook, his former wife, had told the paper that her ex-husband had left it to their two sons to tell her about his remarriage plans. So it had the story I was planning.

This was not a huge blow and in all honesty my thoughts at the time were on deciding the pairings for Sunday to give me a chance of defeating the rather cocky Scots. I thought no more of it until the call came. Robin said he was ringing personally to apologize that my ‘scoop’, as he called it, had been thwarted. I did not like to tell him that the euro story had every chance of being plastered over the front anyway.

Anyway, he and Gaynor had been trying to think of any snippet that they could give me in compensation for losing the wedding story, he said. I concealed my agitation at the rumpus going on behind me and he told me that Gaynor’s first official engagement as his wife would be to attend the Lord Mayor’s banquet on 23 April, when he would be making the traditional foreign policy address.

He told me again about the wedding preparations and, at my urging, gave me a couple of quotes about how they were planning their life together. Job done and I got on with the golf. And his call had been worth it. Under the heading ‘Banquet debut for new wife’ – and with a picture of the couple together at Chevening – I wrote that Gaynor Regan had chosen a glittering City occasion to make her first official appearance as the wife of the foreign secretary. He was later to outwit the press by marrying not at Chevening but at Tunbridge Wells register office ten days earlier than planned.

Cook’s call had shown me another side to this complex man, whom I had known well since the early 1980s. He clearly wanted to help Gaynor into the new role, which was why he was taking so much trouble to call me, but he also felt he owed me after the first version collapsed.

Cook often spoke to me privately about some of the big Labour stories in those years. I regarded him as a bit of a loner in the Commons. Once I ran into him on his own, armed with binoculars, at Newbury racecourse. ‘What on earth are you doing here, Phil?’ he asked. ‘I could say the same,’ I replied. He loved horse racing and had been introduced to it by his first wife. During the 1990s, he wrote a weekly tipster column for the Glasgow Herald. After that chance encounter, and finding out that I, too, liked the sport of kings, I always felt he treated me with a little extra respect.

Cook was a fine parliamentarian and his Commons performance in 1996 – when, after only two hours to read the 200-page Scott Report into the arms-to-Iraq affair, he lacerated ‘this Government which knows no shame’ with a forensic demolition of ministers – was one of the finest MPs on all sides had seen.

His early days as foreign secretary were turbulent because of the marriage breakdown and his claim to be following an ethical foreign policy, which was endlessly scrutinized. I was with Tony Blair in Tokyo in January 1998 when Margaret Cook, in The Times, made damaging new revelations about their marriage. It virtually hijacked Blair’s trip, with the travelling press pack interested in no other story.

After the 2001 election, he was moved against his will to be leader of the Commons, probably because Blair could see an emerging new battle between him and Brown over euro entry. But he was back in the place where he felt most comfortable and set about reforming the hours and practices of the House. I often went down to the vast Leader’s room for a chat in those days and he seemed happy enough. But the Iraq war meant the end of his government career.

On 16 August 2002, I led The Times with a story that Cook ‘would emerge next month as one of the Cabinet’s leading critics of British involvement in any attempt to topple Saddam Hussein’. The former foreign secretary was said by close allies – I suppose it is safe now to admit that it was him – to have deep reservations about the prospect of military action and to be ready to make his case when Tony Blair next invited the Cabinet to discuss Iraq.

Cook, I wrote, regarded Saddam as a severe threat who had to be countered. But he feared that an attempted Western invasion would further damage the prospects of peace in the Middle East and could lead to wider conflict. I said that he would make his interventions in Cabinet and not elsewhere.

It was a strong story and, looking back, Cook was prophetic. On 17 March he resigned from the Cabinet, saying he could not accept collective responsibility over military action. He delivered a thumping, dignified resignation speech that won applause from all sides and was seen by veterans as one of the most effective ever. Cook and Brown buried their age-old animosity and some thought he would return under a Brown administration.

But it was not to be. On 6 August 2005 – just seven years after that conversation on Islay – Cook suffered a severe heart attack while walking in the Scottish Highlands, and died. He was only fifty-nine. I’m not sure many people knew him well, but those of us who had regular chats with him would miss him. And he was a great loss to politics.