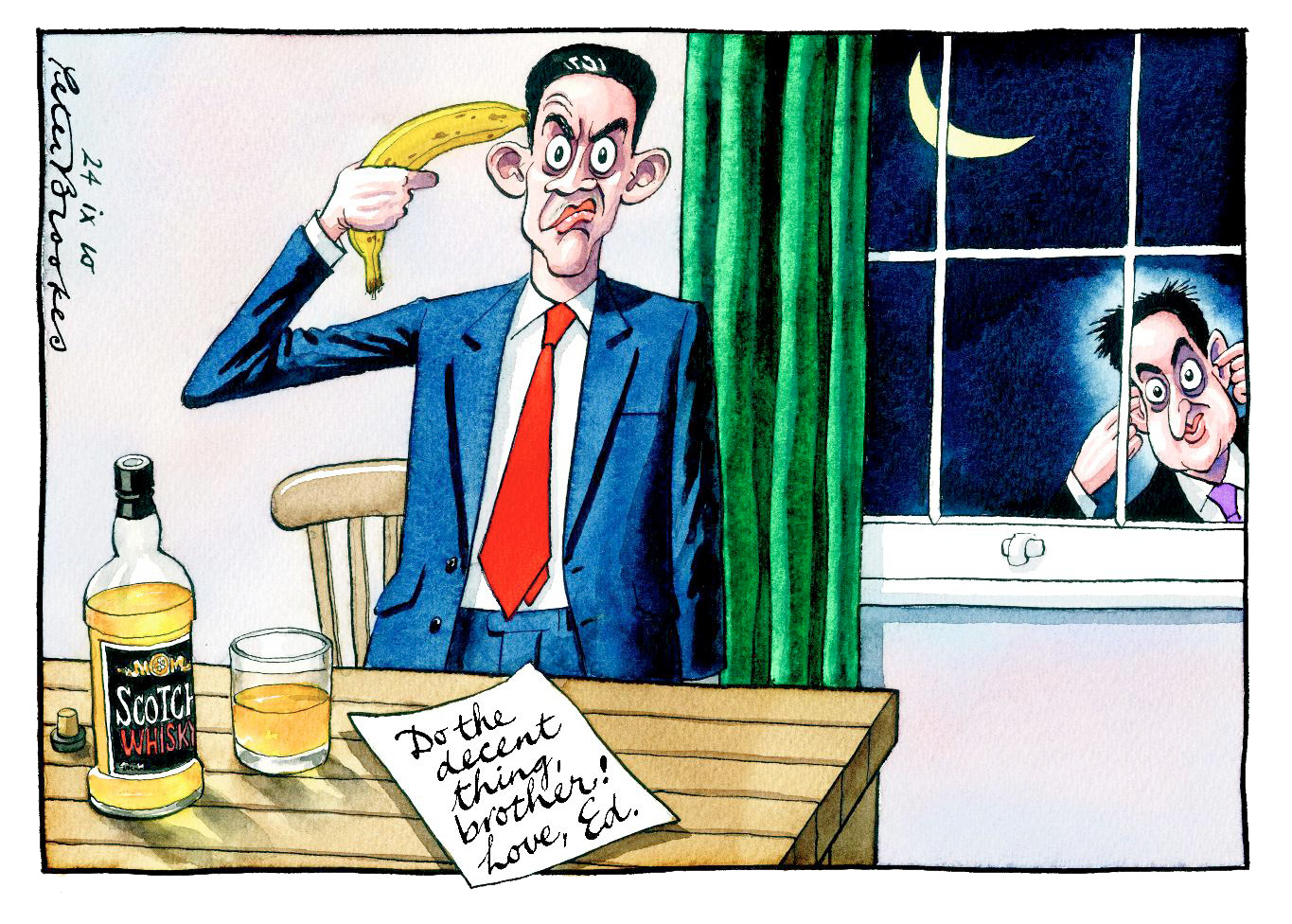

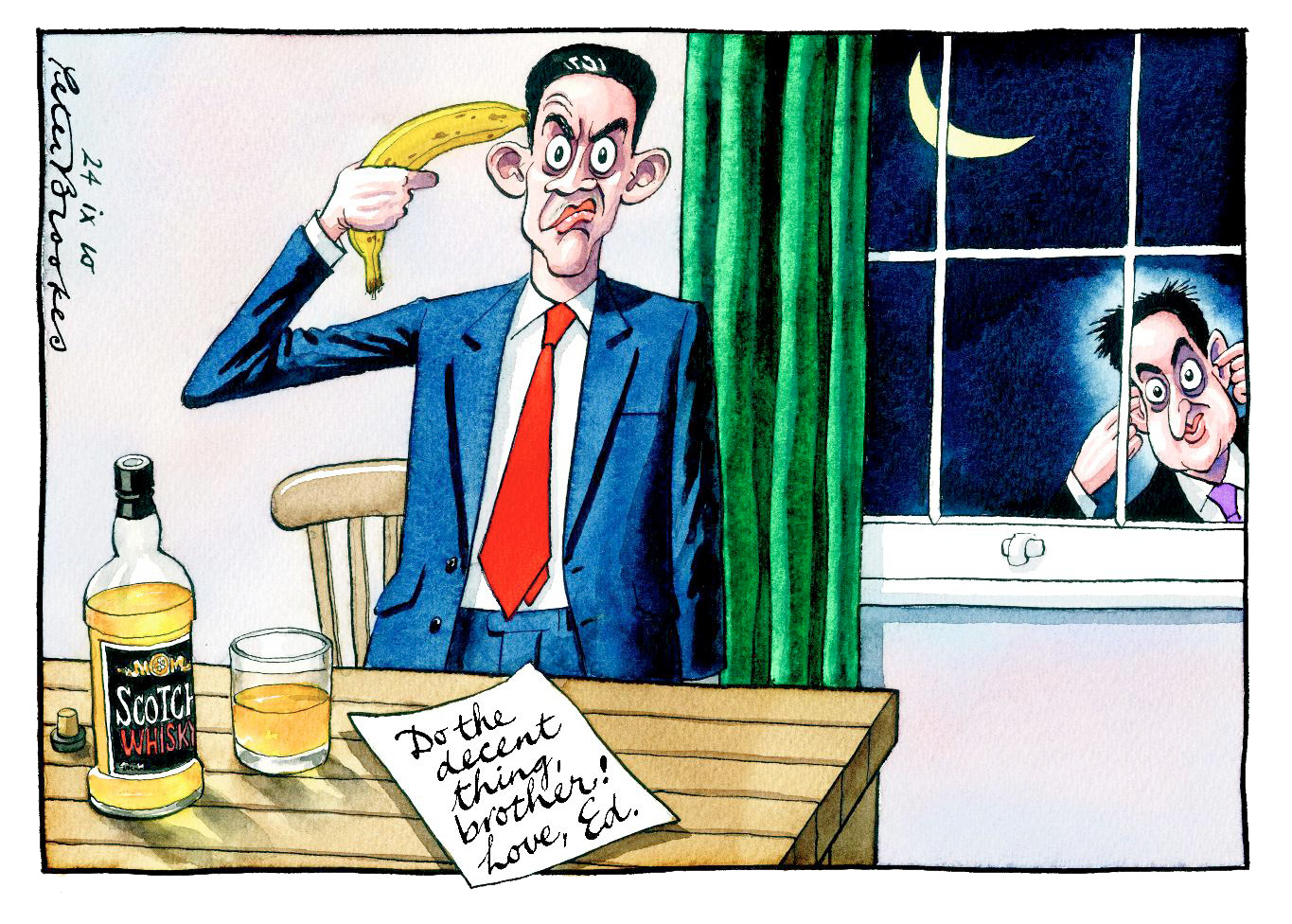

David Miliband spurned at least four opportunities to run against Gordon Brown. But the leadership of the Labour Party was his for the taking if he had made the right moves in 2010.

Gordon Brown’s decision to favour Ed Miliband over his long-time adviser, Ed Balls, undoubtedly helped the younger brother to a victory from which David and the rest of the Miliband family – let alone the Labour Party – have not recovered.

But David Miliband, who served as foreign secretary under Brown, had only himself to blame for a tactical failure that led to his defeat, sources close to Brown, Ed Miliband, David Miliband and Balls have told me as I have retraced one of the most significant and traumatic periods in Labour’s history. We have no way of knowing, but most Labour figures believe that the history of the 2010–15 Parliament would have been different as well, and that Labour would not (as of the summer of 2016) be under the stewardship of a hard-left MP who had never been anywhere near his party’s front-bench.

The move that would have ensured David Miliband’s victory would have been to indicate that Ed Balls, one of the other four candidates, was set to be his shadow chancellor, key figures from the different factions agree. It would have brought together the Blairite and Brownite wings of the party and undoubtedly taken votes away from Ed Miliband. Both James Purnell, one of David’s best friends, and Peter Mandelson urged him to bury his reservations about Balls and do it for the Labour Party but he refused.

It was, after all, because he believed that a David Miliband–Balls deal would have led to victory for the older Miliband brother that Gordon Brown desperately tried to stop such a deal being reached. And Peter Mandelson remains very disappointed that David Miliband did not make the move that would have ensured his victory.

‘We don’t know for sure but I think it is most likely that a Miliband-led Labour Party would have got into power in one form or another in 2015, perhaps in a hung parliament deal with the Liberal Democrats,’ Mandelson told me. He continued:

If he had won the leadership, none of this nonsense that has happened since would have occurred. We would not have had the five wasted years and we would not have been in the madcap situation we are at the moment.

But David was either too proud or too complacent to do what he was urged, which was to form an alliance with Ed Balls. You know that at the time I was talking a lot to Ed Balls. I knew his mind. But David would not do it. The trouble was he never believed he would lose. But in these situations you have to talk to anyone who will listen to you. That’s what Tony did in 1994. Of all the tragedies to strike Labour, this was the biggest in recent years.

Stewart Wood, an adviser to Brown and later Ed Miliband, believes that David Miliband did not countenance an arrangement with Balls because he was going to take a different economic line to Balls if he won:

Ed was proposing reducing the deficit at a slower pace and in his Bloomberg lecture of August 2010 was effectively saying there was an alternative to the kind of austerity Osborne was proposing. David obviously did not want that, and so he did not take the obvious avenue open to him.

As The Guardian revealed in June 2011 – when it got hold of the final draft of a speech David Miliband would have delivered had he won – he planned to warn that the great danger to his party lay in underestimating the challenge of the deficit. He had been planning to announce that Alistair Darling, the former chancellor, would head a commission to draw up rules on deficits and public spending designed to restore lost trust in Labour’s fiscal discipline.

As Damian McBride reveals in his book, Power Trip, Brown called him out of the blue during the election – McBride had stopped working for him in 2009 in the row over his leaked e-mails containing his suggestions for smearing top Tories – and told him that if he was speaking to Ed Balls, he should tell him not to do a deal with David Miliband but to do one with Ed Miliband instead. McBride wrote: ‘Gordon and others close to him urged me that – if I had any influence over Ed Balls or his team – I should tell him he had to reject any deal offered by David, and instead pursue the same deal with Ed Miliband.’

The call surprised McBride, but it showed the former leader’s determination to stop David at any price. By that stage Balls was not talking very much to Brown. One of the most successful political relationships of the Labour years was, if not in deep freeze, frostier than anyone realized at the time.

Brown’s stance – while it may well have helped Ed Miliband in the ultimately decisive union section of the electoral college – would not have stopped David if he had intimated he was ready to embrace Balls. Balls was eliminated at the third stage of the contest, Diane Abbott and Andy Burnham having dropped out previously. At that point, Balls had 43 votes from MPs, Ed Miliband 96 and David 125.

However, after Balls dropped out, 26 of his votes went to Ed Miliband and only 15 to David. Although David won the MPs’ section by 140 to 122, just three more switching to him from Ed Balls would have been enough to win the leadership. Everyone I have spoken to says that the hint of a deal with Balls would have easily done the trick. According to friends, however, David Miliband was determined to win on his own terms, and believed that he was going to do so. One close friend said: ‘In his own mind he could never quite accept that Ed Miliband would beat him. When it comes to hard politics David is a bit of an innocent.’

The key to winning the election was lining up the second preferences of MPs known to be voting for someone else. So Ed Miliband spent hours talking to MPs, asking them politely if he could be their second choice and that he totally understood why he was not the first. David Miliband, according to one of his close aides, lined up those MPs who were known to be backing Ed Balls and ‘treated them like a group of naughty children’. Several gave Ed Miliband their second preferences – which in the end, of course, decided the race for him – because he had been so understanding and David had not.

One story that has done the rounds ever since was of a newly elected Labour MP who let it be known that she was keen to vote for David Miliband. She sought a meeting with him to tell him, only to be told by his office that one of his team would be talking to her. When she ran into Miliband in the corridor, he acknowledged her and said: ‘Ah yes, I must organize for one of the team to talk to you.’ That was not the kind of attitude to win friends and influence them.

The other huge problem was that David Miliband, according to another friend, was trying to run before he could walk. He was thinking more about how he would take on David Cameron than what he needed to do to beat his brother. The great obstacle to a deal with Ed Balls in his own mind was that the man whom others were telling him to make shadow chancellor wanted to reduce the deficit at a slower pace than currently suggested by the Government at the time.

Under the putative deal, David Miliband would have made positive remarks about Ed Balls, which would have been an obvious hint that he would be shadow chancellor and a clear signal to the supporters of Balls to make David Miliband their second preference choice. The Tory Government was accelerating its cuts plan, but David Miliband did not want a dividing line at this stage because he believed it was his task to rebuild Labour’s shattered economic credibility. To him Balls, someone who was so closely associated with Brown, was an obstacle. But he was not thinking enough about the job in hand.

‘He was already worrying about how he would face up to David Cameron in the House of Commons if he was being seen to relax a bit on austerity. It was crazy,’ a close friend said. Phil Collins, former speechwriter for Tony Blair and then working at The Times as a leader writer, also urged Miliband to work with Balls, and said as much in an article at the time.

Similarly, Miliband had balked during one of the election hustings when asked whether he would line up with TUC protests against the cuts. Other contenders had said they would; he prevaricated. A colleague said: ‘David was not really a politician. He did not get the whole business of alliances. He was far too obsessed with what was to come after and how he would look up against Cameron rather than with winning against Ed.’

Another friend said: ‘He should have gone to Ed Balls. Ed [Balls] could hardly go to him because he was the underdog. But David was being told by lots of his friends this was the way to win and he was stubborn.’ And still another former Brown aide told me: ‘In the end Gordon backed Ed Miliband because he thought that was the way to stop David Miliband. History would have been different if David had done a deal with Ed Balls. He would have won.’

There had been one other opportunity for David Miliband, back in 2007 when Gordon Brown took over. Many of the Blairites wanted him to have a go at that time. He also, I’ve since discovered, got unsolicited advice from a former Tory MP. David Martin, who represented Portsmouth South for ten years, wrote to him quoting Brutus in Julius Caesar: ‘There is a tide in the affairs of men … Which, taken at the flood, leads on to fortune.’ Miliband wrote a polite letter back to his correspondent telling him he had decided against standing. Martin had given the same advice to Michael Portillo in 1995 when he stepped back from challenging John Major.

Gordon Brown believed that Ed Miliband should offer Ed Balls the shadow chancellorship as a way of uniting the two men who had served him for so long. Stewart Wood, Ed Miliband’s adviser and formerly Brown’s too, backed the suggestion. But Miliband told him it would be a bad idea. ‘Ed said that while David, his brother, would be seen as the Blairite candidate, Balls would be seen as a Brownite candidate, allowing him [Ed Miliband] to be seen as the change candidate,’ Wood told me.

As it happened, of course, Miliband did it without having to offer a deal to Ed Balls. The majority view appears to be that David would have won if he had offered some kind of deal to Balls, however informal. But everyone around Ed Miliband at the time talks of his strong confidence in his chances. Wood’s disclosure shows how confident Ed Miliband was that he could do it on his own, and how his strategic brain was working at the time. It also shows why he first appointed Alan Johnson as his shadow chancellor, only for Johnson to stand down for personal reasons in his first year. It was only then that he appointed Ed Balls to the job for which his talents seemed well suited.

The Brown–Balls partnership had survived most of the Labour years but during the Brown premiership it came under strain. McBride tells of how, rather than back the man who was his more senior adviser, and the one on whom he had relied for so long, Brown decided to give both Balls and Ed Miliband a chance to succeed him.

Both Eds became secretaries of state when Brown became leader. McBride reports that at the 2007 party conference, Brown had instructed him to:

… build up the young guys. Turn it into a beauty contest about who’ll take over from me. Don’t for God’s sake say I won’t serve a full term but say ‘Brown doesn’t want to go on forever. Brown will start putting the next generation into all the senior posts and one of them will become leader.’

McBride asked him which names he should put out there and was told James Purnell, Ruth Kelly, Andy Burnham, Yvette Cooper and Balls. He also mentioned Miliband and Miliband and when McBride queried this he said: ‘Both of them … You need to watch Ed Miliband. He’s the one to watch.’ Brown also told McBride that one day he would have to choose between the two Eds. McBride believes that to have said this to him, and presumably others, was a mistake because from then on people who had seen them as an indivisible double act began to treat them as separate entities and inevitably took sides.

Deep down Brown knew that probably one day he would have to choose too, and if a Blairite contender like David Miliband or Purnell became the frontrunner he would have to back the one he felt most capable of setting out an alternative Brownite vision. Brown’s conversation with McBride was a revelation to his former aide. It showed him that when decision time eventually arrived Ed Miliband had a serious chance of getting the backing of Brown. Brown’s appreciation of Ed Miliband was limited, though. He once told Mandelson: ‘He’s more a preacher than a politician. He’s never had to make a difficult decision in his life.’

The alliance between Balls and Brown had become strained long before the leadership contest. Balls was frustrated that in the run-up up to the 2009 reshuffle, Brown had allowed the suggestion to gain credence that he wanted him in the Treasury to replace Alistair Darling. In fact, as already mentioned elsewhere, Balls wanted longer in the post of schools secretary to enhance his reputation as a politician who could handle an important government department.

The James Purnell resignation on the eve of the reshuffle put paid to any suggestion of moving Darling, but it was still presented as a defeat for Balls – something his friends knew was far from the case. I was called by Ed Balls on the Tuesday of what would have been reshuffle week – and I gathered that other journalists had been as well – to be told that stories about Brown wanting him to go to the Treasury were wrong. But that did not stop some papers being briefed after the Purnell shock that it had stopped Darling being replaced by Balls. Balls was exasperated. So as they entered the last months of the parliament, the two men who had worked together on so many of the key decisions of the Labour Government were no longer as close as they once were.

For Balls, the last straw came at the start of 2010, when the PM faced the last attempted coup on his leadership. As detailed previously, Geoff Hoon and Patricia Hewitt, the former Cabinet ministers, had suddenly called for a secret leadership ballot in a last-ditch attempt to remove Brown, just months before the election. It was no more successful than any that had gone before, but several ministers – who delayed for hours before giving their support to the beleaguered Prime Minister – extracted concessions from him about the coming campaign and his attitude towards the cuts in public spending needed to tackle the deficit, about which they felt he was in denial.

Ironically, Balls was one of the few to go out publicly and support Brown from the start. But to pacify some of the dissident ministers, Brown apparently told them he would restrain the influence of Balls, who was still seen still to have a big say in policy and strategy. At Brown’s request, Balls had been making occasional visits to Number 10 for strategy chats.

Balls was furious when Brown allowed his team, using the evidence of those occasional chats, to brief the press that he – the most senior figure in Brown’s inner circle – was to be ‘reined in’. The episode damaged their relationship for good.

Together Brown and Balls had shaped the early years of the New Labour Government, making the Bank of England independent and keeping Britain out of the euro. But eventually even their close bond was broken by the strains that politics will always impose.