2

A MAN-MADE PANDEMIC

How Chemicals Have Fueled the Onslaught

Could [Parkinson’s disease] be a true man-made disease?

—Dr. William Langston, who identified MPTP as a cause of parkinsonism, in 19971

IN 1961, NEUROLOGISTS FROM ALL OVER THE COUNTRY GATHERED in Atlantic City, New Jersey, for the eighty-sixth annual meeting of the American Neurological Association. They caught up with old friends, exchanged gossip on the boardwalk, and heard an intriguing new idea from two Harvard neurologists, Drs. David Poskanzer and Robert Schwab. They argued that Parkinson’s disease would disappear “as a major clinical entity by 1980.”2

The roots of their claim lay in Vienna during World War I. An Austrian pilot named Constantin von Economo, who had been stationed on the Russian front, returned to the city to resume his career as a neurologist. It was 1916, and his country needed him to care for wounded soldiers.3

In addition to tending to veterans with head injuries, von Economo saw patients with a strange new disease. The illness, which he described as a “sleeping sickness,” would strike individuals out of the blue. He observed that people were “falling asleep while eating or working… frequently in a most uncomfortable position.”4 After this abrupt onset of sleep, a headache, nausea, and fever followed. Many would go into a coma and die.

The sleeping sickness spread throughout Europe and North America and affected about 1 million people worldwide between 1915 and 1926.5 Then it vanished. By 1928, there were no new cases of the mysterious illness. Since then, only rare incidences have been reported.6

Those who recovered often developed different symptoms months or even years later. These included slow movements, stiffness, and tremors. They had what looked like Parkinson’s disease.7 The only differences were that these individuals were young and that a preceding infection had triggered the disease. Some were teenagers.8 For decades, they would remain in physically frozen states, unable to move or communicate.

Dr. Oliver Sacks, the neurologist and author, described many of these patients in his classic book Awakenings. They had endured von Economo’s sleeping sickness only to develop profound parkinsonism years later. He wrote, “Stares of immobility and arrest… started to roll in a great sluggish, torpid tide over many of the survivors.”9

The patients were “as insubstantial as ghosts, and as passive as zombies,” Sacks wrote. They “were put away in chronic hospitals, nursing homes, lunatic asylums, or special colonies. [They] were totally forgotten.… And yet some lived on.”10

Sacks was working at a psychiatric hospital in the Bronx in the 1960s when he first encountered Leonard Lowe. At forty-six years old, Lowe was mute and frozen except for tiny movements of his right hand. Lowe had developed the first sign of parkinsonism when he was a teenager. “His right hand started to become stiff, weak, pale, and shrunken,” according to Sacks. The symptoms slowly progressed, but Lowe, an avid reader, was still able to graduate from Harvard with honors. Later, when he was working toward his PhD, “his disability became so severe as to bring his studies to a halt.”11 Lowe and patients like him were “awaiting an awakening.”12

That awakening came in March 1969. Two weeks after Sacks started Lowe on levodopa (Box A), “a sudden ‘conversion’ took place. The rigidity vanished from all his limbs, and he felt filled with an excess of energy and power. [He] became able to write and type once again, to rise from his chair, to walk with some assistance, and to speak in a loud and clear voice.… He enjoyed a mobility, a health, and a happiness which he had not known in thirty years.”

Unfortunately for Lowe, levodopa’s benefits were transient. The drug caused involuntary movements and aggressive behavior that led Sacks to stop the medication. Lowe, who would later be depicted by Robert De Niro in the movie Awakenings, never recovered. He died in 1981.

In the 1950s and 1960s, Poskanzer and Schwab, the neurologists who caused a stir at the meeting in Atlantic City, were also caring for individuals like Lowe. They believed that most cases of Parkinson’s disease were due to the sleeping sickness. They thought that as these individuals died off, so, too, would the disease.13

Poskanzer was so certain of his view that in a 1974 Time magazine article, he said, “I offer a bottle of Scotch to any doctor in the U.S. who can send me a report of a clearly diagnosed case of Parkinson’s in a patient born since 1931.”14 Of his bet, Dr. Poskanzer reported, “So far it’s cost me 14 bottles—just 14 of these younger patients identified.” The article in Time concluded, “[There] should be many fewer such patients [with Parkinson’s disease] in the future—provided, of course, that Poskanzer wins his bet.”

Poskanzer, of course, lost. While most of his contemporaries had supported his and Schwab’s contention, a few did not.16 Dr. Margaret “Peggy” Hoehn was a pioneering neurologist at a time when few women were even admitted to medical school (Figure 1). Born in San Francisco in 1930 and trained in Canada and then at Queen’s Square in London, Hoehn would become an associate professor of neurology at Columbia University and one of the world’s leading authorities on Parkinson’s disease.

Two years after Poskanzer’s bold bet in Time, Hoehn made a distinction between the parkinsonism due to the sleeping sickness that von Economo described and the classical Parkinson’s disease that James Parkinson had encountered.17 The former was a consequence of a mysterious illness that had since disappeared. The second was rising in frequency. Even before Poskanzer’s wager, Hoehn had demonstrated that the parkinsonism due to sleeping sickness was relatively rare. And as we know, far from disappearing, the number of people with Parkinson’s has soared.

Over the last twenty-five years, Parkinson’s disease is the only neurological disorder whose burden as measured by deaths, disability, and number affected have all increased even after adjusting for age.18 And the estimates are almost certainly low due to underreporting and missed or delayed diagnoses.19

THE ENGINE OF A SPREADING DISEASE

Dr. Parkinson wrote his 1817 essay in London, so it is linked in time and place to the height of the Industrial Revolution. The spread of the disease has closely tracked the growth of industrialization.

The new chemicals that this era has wrought are likely driving the spike in Parkinson’s. Dozens of studies—both of humans and of animals in the lab—have linked the two. The list of known hazardous substances is extensive and goes beyond the pesticides paraquat, rotenone, and Agent Orange. It includes certain solvents, air pollution, and some metals, such as manganese used in welding.20 Almost all of us have been, are, and will be exposed to these risks. Unless we want more of us to develop Parkinson’s, we will have to change our practices.

The use of synthetic pesticides (Box B) began in earnest after World War II. By 1990, production soared to over 3 million tons per year, or more than a pound per person.21 Between 1990 and 2016, the amount of pesticides increased by another 70%.22 Over that same period, China’s annual use of pesticides doubled from 0.8 million tons to 1.8 million. Each year, the country uses more than 2.5 pounds of pesticide for every person.23

Pesticides have improved crop yields and lowered costs, and many, if not most, are not linked to Parkinson’s.24 However, some of the most frequently used pesticides are associated with an increased risk of the disease. Given that there are pesticides that don’t pose a Parkinson’s risk, we can and should eliminate the ones that are known to be toxic to dopamine-producing brain cells.

Pesticides, of course, are not the only industrial product whose use has increased. Solvents, which are used to dissolve other substances (Box C), arrived in the latter half of the nineteenth century from the coal and tar industry.25 Since then, these chemicals have evolved countless applications in consumer and industrial products, including in cosmetics, cleaning solutions, paints, pharmaceutical products, and automobile production.26 By one estimate, 8% of the working population regularly uses solvents.27 Almost all of us are exposed to them at home in the skin products that we use, the cleaning agents in our cabinets, the paints in our garages, and even the pills that we take.

Trichloroethylene, which is linked to Parkinson’s disease, is one of the most common industrial solvents. Its production is on the rise globally, especially in China.28

Researchers have also found that air pollution increases the risk of Parkinson’s.29 Very small inhaled toxic particles can bypass the brain’s normal protective mechanisms, injuring it directly. And air pollution has increased exponentially worldwide in step with global industrialization. The toxic smog in China’s rapidly industrializing cities is comparable to the London fogs of the early Industrial Revolution.

Not surprisingly, the rates of Parkinson’s have been increasing the most in industrializing countries. Over the last twenty-five years the prevalence rates for Parkinson’s, adjusted for age, increased by 22% for the world, by 30% for India, and by 116% for China.30

The burden of Parkinson’s falls more often on men, who are more likely to work in occupations that expose them to industrial products linked to the disease. In the United States, for example, men make up 75% of farmers, 80% of metal and plastic laborers, 90% of chemical workers, 91% of painters, 96% of welders, and 97% of pest control workers.31 Men also have a 40% greater risk of developing Parkinson’s than women.32

THE AGE FACTOR

One of the greatest human accomplishments of the twentieth century was the doubling of life expectancy.33 In 1900, the average life span globally was just thirty-one years; by 2000, it was sixty-six.34 The result is that the number of people over age sixty-five is increasing (Figure 2).

But as we age, the likelihood that many of us will develop Parkinson’s increases.35 Aging itself, though, is not likely the cause of the disease. Rather, living longer allows time for nerve cell loss to occur and, therefore, for Parkinson’s to develop.37

FIGURE 2. World population sixty-five and older, 1990–2040.36

The environmental and genetic factors that contribute to Parkinson’s require time for the damage to become apparent. The actual onset of the disease likely begins twenty or more years before symptoms like tremors appear.38 During this period the disease may be spreading from the gut and nose to lower and then higher areas of the brain. As it stealthily takes hold and time passes, more nerve cells die. It’s only when about 60% of nerve cells are gone that the typical features of Parkinson’s finally show up.

And so, as the population of older people increases, so too will the number of individuals who experience Parkinson’s disease. In fact, a person’s risk rises sharply with age. Beginning in a person’s forties, the risk of Parkinson’s roughly triples with each passing decade.39 In 2019 alone, 60,000 individuals, or over 1,000 Americans per week, were diagnosed with Parkinson’s.

And we will keep living longer and longer. Recent headlines have highlighted small declines in life expectancy in the United States due to suicides and the opioid epidemic, but the long-term trend remains on an upward trajectory.40 By 2030, there will be a 10% higher risk of a forty-five-year-old individual eventually developing Parkinson’s disease than there is today.41 With increasing longevity, more of us will face Parkinson’s.

THE SMOKING PARADOX

Smoking’s link to lung cancer provides a model for understanding the connection between environmental risk factors and Parkinson’s disease. Like Parkinson’s, lung cancer was once very rare.42 Before the introduction of cigarettes, lung cancer was so uncommon that, according to Robert Proctor, a historian at Stanford University, “doctors took special notice when confronted with a case, thinking it a once-in-a-lifetime oddity.”43 With the industrial production and mass marketing of cigarettes in the late 1800s, however, lung cancer rates soon swelled.44

At the end of World War II, Britain had soaring rates of lung cancer, and no one knew why. Some speculated that dust from tarred roads might be the cause; others blamed poison gas from World War I.45 To answer the question, Drs. Richard Doll, a physician and epidemiologist, and Bradford Hill, a statistician, conducted a simple study in 1951. They surveyed nearly 60,000 British physicians. They asked participants for their names, ages, and addresses. They also asked the doctors about their smoking history. The researchers then recorded the number and causes of deaths that subsequently developed in this group of physicians. They found a steadily rising mortality from lung cancer as the amount of smoking increased.46 Further studies supported these results, leading to the conclusion that smoking caused lung cancer.47

With lung cancer, as with Parkinson’s, the environmental risk has to occur over many years. Individuals who smoke for only brief periods (years and not decades) have a much lower risk of lung cancer.48 In both diseases a lag is present between exposure and the development of disease.

In addition, the risk of lung cancer drops after people stop smoking.49 This is the kind of opportunity that we should seek out in the case of Parkinson’s—reducing our future exposure to the environmental risks linked to the disease.

Smoking has a counterintuitive connection to Parkinson’s too. It actually decreases the risk of getting the disease—by an astonishing 40%, according to numerous studies.50 The reason that smoking may lower the risk has yet to be determined. Some studies suggest that nicotine may protect nerve cells; others indicate that smoking may increase the breakdown of environmental toxins.51

Smoking might also confer its protective benefit by way of the nose or the gut.52 It may block or otherwise interfere with the entry of the external factors that cause Parkinson’s. Fumes from smoking are, of course, inhaled, and this changes the covering of the nasal passages and the local immune response.53

Smoking also changes the gut. The gut microbiome—the community of bacteria that live in our intestines—is remarkable. Over 100 trillion bacteria, far more than the number of human cells in the body, call us their home.54

Recent research has demonstrated that smoking and Parkinson’s may affect the gut microbiome.55 For example, smoking increases the population of certain bacteria that may boost the barrier function of the gut.56 This barrier, the lining of our intestines, is the major interface between the environment—what we ingest—and ourselves. Its ability to keep out harmful substances is key.

So smokers’ elevated levels of bacteria may help barrier function, thus potentially protecting them from toxins that up Parkinson’s risk. Or perhaps their robust numbers of certain kinds of bacteria are keeping other kinds of harmful bacteria in check—bacteria that could be a factor in the development of Parkinson’s. In a 2016 study, gut bacteria were shown to contribute to the development of the disease.57 When genetically altered mice received antibiotics to kill off the bacteria in their guts, the pathology of Parkinson’s was reduced.

Even more remarkably, this contribution from gut bacteria may be transmissible. When mice were given fecal material (which has numerous gut bacteria) from people who didn’t have Parkinson’s, the motor function of the mice was unchanged. However, when the mice received fecal material from people with Parkinson’s, their motor function worsened. These results suggest that the gut bacteria may be influencing the brain. More research is required to explore the emerging gut-brain axis of disease, including the surreal possibility that poop transplantations may one day treat Parkinson’s disease.58

Regardless of what the potential benefits of smoking might be, no one should smoke—or continue to smoke—to reduce the risk of Parkinson’s. A causal relationship to the disease has not been proven. And the negative effects of smoking, including losing, on average, a decade of life, far outweigh any potential upside related to Parkinson’s.59

Taken together, the increases in industrialization and aging and declines in smoking are likely to raise the future burden of Parkinson’s far above the 12.9 million that we previously estimated. Future projections that account for these factors could lead to Parkinson’s affecting 17.5 million people by 2040.60 A far cry from the twenty-two who died of the condition in 1855 in England.61

A NEW KIND OF PANDEMIC

“Epidemiology is the study of what ‘comes upon’ groups of people,” according to the late population health expert Dr. Abel Omran.62 For most of human history, what has come upon people are famines and infectious diseases, sometimes in the form of a pandemic. As opposed to epidemics, which are limited to a given community, pandemics cover large geographic areas.63 The black death killed up to 200 million people throughout Europe and Asia in the fourteenth century.64 The influenza pandemic of 1918 killed between 50 million and 100 million people worldwide and led to an unprecedented drop in global life expectancy.65

Thanks to public health advances, infectious diseases are no longer the leading source of death and disability. The new leader of the pack is chronic conditions.66 In his landmark 1971 paper on population change, Omran called our current era the “Age of Degenerative and Man-Made Diseases.”67 Among these are cancer, diabetes, heart disease, and Parkinson’s.68

This transition has led some to expand the definition of “pandemic” to include diseases that are not infectious. The new carriers, or “vectors,” of these diseases are not bacteria or viruses but urbanization, population aging, globalization, and the widespread availability of unhealthy products.69

Parkinson’s disease satisfies many of the criteria of a pandemic (Table 1).70 The disease is found everywhere in the world.71 In almost every region, the rate of Parkinson’s is increasing.72 In addition, as with infectious pandemics, Parkinson’s disease appears to be spreading and growing as industrialization expands.

TABLE 1. Characteristics of a pandemic.73

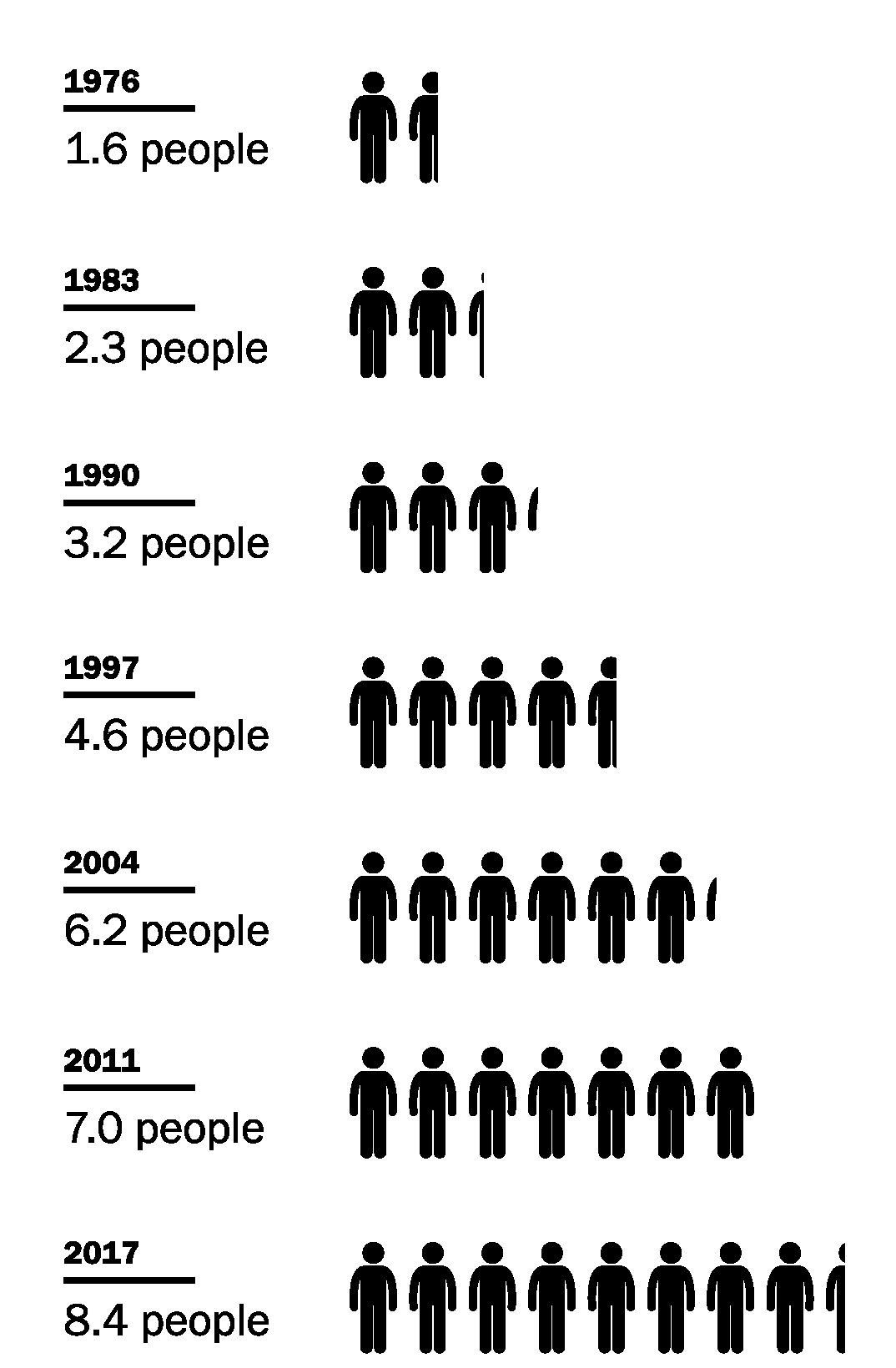

FIGURE 3. Number of deaths per 100,000 people due to Parkinson’s disease in the United States, 1976–2017.74

China is one extreme example. As the country experiences rapid economic growth, it also has increased its use of pesticides and industrial solvents and has incredibly poor air quality.75 Not surprisingly, China also has the fastest-rising rate of Parkinson’s in the world.76

As with other pandemics, the disease is severely debilitating. Over its average fifteen-year course, Parkinson’s leads to progressive loss of independence and often nursing home care.77 Although improved therapies have increased survival, it remains a deadly condition. Death rates from the disease are climbing in the United States (Figure 3), where it is now the fourteenth-leading cause of death.78

Poskanzer and Schwab were unfortunately very wrong to predict an imminent end to this formidable condition. A wave of Parkinson’s disease is upon us. And it affects everyone (Figure 4): Democrats (Reverend Jesse Jackson) and Republicans (Senator Johnny Isakson); Catholics (Pope John Paul II) and Protestants (Reverend Billy Graham); capitalists (Jonathan Silverstein) and communists (Deng Xiaoping); activists (Walter Sisulu), actors (Alan Alda), actresses (Deborah Kerr), astronauts (Rich Clifford), and attorneys (Janet Reno); boxers (Muhammad Ali), cyclists (Davis Phinney), and runners (Sir Roger Bannister); baseball (Kirk Gibson), basketball (Brian Grant), football (Forrest Gregg), and hockey (Nathan Dempsey) players; journalists (Michael Kinsley) and photographers (Margaret Bourke-White); singers (Linda Ronstadt) and songwriters (Neil Diamond).

Humans have successfully confronted other diseases in the past—when they did not know what was coming. Parkinson’s is different. We know it is bearing down on us. So we have a chance to learn from previous fights and prepare.